22 INDIAN RIDGE LOOP

KEY AT-A-GLANCE INFORMATION

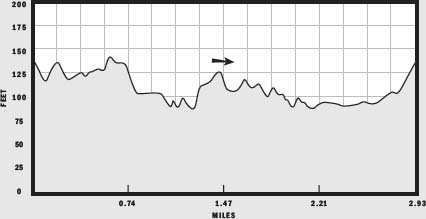

LENGTH: 2.93 miles

CONFIGURATION: Loop

DIFFICULTY: Easy to moderate

SCENERY: Woods, meadowland, pond, views from two tall eskers

EXPOSURE: Mostly shade

TRAFFIC: Moderate

TRAIL SURFACE: Gravel, packed earth, and some muddy areas

HIKING TIME: 1.5–2 hours

SEASON: Year-round sunrise–sunset

ACCESS: Free

MAPS: Andover Village Improvement Society (AVIS) guides can be purchased at the Andover town hall and from Moor & Mountain (3 Railroad Street, North Andover, [978] 475-3665). GPS coordinates and directions for the many Andover Bay Circuit Trail links can be found at www.baycircuit.org/section3.pdf.

FACILITIES: No

SPECIAL COMMENTS: Andover offers hikers a tremendous number of trails through hundreds of acres of conservation land. By accessing the 200-mile-long Bay Circuit Trail, short jaunts can easily be expanded into lengthy expeditions.

WHEELCHAIR TRAVERSABLE: No

DISTANCE FROM BOSTON COMMON: 24 miles

Indian Ridge Loop

UTM Zone (WGS84) 19T

Northing: 4724791

Easting: 322608

Latitude: N 42° 39' 19"

Longitude: W 71° 09' 52"

Directions

From Boston, take Storrow Drive east and merge onto I-93 north (Concord, NH) via the ramp on the left. At 21.1 miles, take Exit 43 to MA 133 east toward Andover. Bear right onto MA 133 and continue 0.8 miles. Turn right onto Cutler Road and follow it approximately 0.4 miles to the intersection at Reservation Road. Park beside the West Parish Garden Cemetery.

IN BRIEF

This hike links three properties conserved by AVIS. Starting in woods beside Andover’s historic West Parish church, the hike crosses a meadow then negotiates a 50-foot-tall esker, dips to wetland, continues over a second esker, then loops around a large beaver pond to end feet from the start.

DESCRIPTION

Starting at Cutler Road, hike southeast several hundred yards to a large Andover Village Improvement Society (AVIS) sign indicating the trailhead on the left of Reservation Road, then continue northeast across a wooden footbridge several yards into woods brightened in summer by blossoming waist-high jewelweed.

After traveling along the level banking of a stream, the trail departs the damp shade of the woods to cross a meadow. In the near distance, the starch-white spire of the West Parish church stretches to the sky like the righteous boughs of goldenrod blending with the green below. Curving eastward over the domed field once grazed close by cows and now mowed by AVIS on a schedule that coordinates with bobolink nesting, the narrow trail parts clusters of milkweed and clover then returns to woods.

Wetland formed 10,000 to 12,000 years ago by the Wisconsin Glacier lies at the base of the field; here the trail continues across a lengthy span of boardwalk. A harbor for species such as high-bush blueberry, ferns, and skunk cabbage, this primordial morass sets the stage for the equally striking glacier work that lies ahead.

Conveyed to a gravelly crossroads on the far side of the boardwalk, the trail continues to the right heeding Bay Circuit Trail markers as they lead up an esker’s slope of cascading glacial grit. Climbing higher and higher, the trail eventually reaches the height of the rooftops of neighboring houses.

As suburbs spread and tracts of land are leveled and filled by graders and bulldozers, it is easy to lose sight of the terrific geologic activity that shaped the New England landscape. However powerful and transformative the human impact on the land, this enormous mound, like 30-foot ship-crushing waves it matches in size, demonstrates the superior strength of nature. Formed of silt carried by meltwater beneath hundreds of feet of ice, this esker is a quiet but vivid reminder of the significance of climate conditions.

Passing well over the heads of the students and faculty of the school nestled on the esker’s northwestern flank, the trail continues south, rising and dipping along the rocky ridge. Sheathed in the foliage of oaks, hickories, maples, and birches, the esker provides a well-camouflaged vantage point—a fact that wasn’t lost on the generations of Algonquians and Pennacook who hunted here until Chief Cutshamache of the Pennacook sold the territory to white settlers for six pounds and a coat in the early 17th century.

Before King Philip’s War in 1675–1676, relations between the Algonquians, the Pennacook and the settlers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony were generally peaceful, if tenuously so. Practical knowledge the Pennacook passed on to the settlers of Andover certainly helped keep many alive through the plantation’s early years before farms were well established. Reciprocally, the Pennacook and Algonquians, who had long been subjected to Mohawk aggression, gained a crucial ally in the English. Change was set in motion, however, in 1662, when the Wampanoag chief Massasoit’s eldest son, Alexander (Philip’s brother), was summoned at gunpoint to a meeting by the Plymouth Court and died soon after of what was suspected to be poisoning. The incident enraged the Wampanoag, who read the hostile actions of Plymouth’s leaders as part of a power play intended to control and subdue them. This event precipitated the ultimate collapse of King Philip’s well-tested tolerance of the whites.

At a point where the esker subsides and lists southwest, another, smaller esker joins in to the right, forming a deep valley between them. Continue straight following Bay Circuit Trail markers ignoring paths entering and departing from either side. Beyond a stand of young pines, a vale, and a rise, the trail arrives at an AVIS bench placed on one of Indian Ridge’s highest points.

At the split on this downhill run, bear left onto a trail that leads to an oak-filled dell lying between wetland and the esker now tapering eastward. Crossing this floodplain, the trail soon arrives at a junction; bear left here and continue east on the Bay Circuit Trail. Bear left at the split that follows, then right at the next to mount another, smaller esker. At the top, a boulder dressed with a bronze plaque memorializes Andover conservationist Alice Buck, who in 1896 led a crusade to save Indian Ridge as permanent open space.

Arriving at the esker’s southern end, the route dips back to lowland, turning sharply north upon reaching level ground (the Bay Circuit Trail continues south to join Reservation Road). White pines fill this glade with few hardwoods in sight as the trail gradually rises again on a gentle grade. Another fork comes quickly; here choose the left prong to hike on toward Indian Ridge.

Along this stretch, several superficial paths cut in from the left and right; disregard these and climb an esker tail to return to a triangular crossroads marked with the familiar white bars of the Bay Circuit Trail. Do not pick up the Bay Circuit Trail—instead, bear sharply left on a second esker tail to exit onto Reservation Road and continue to Baker’s Meadow. Cross this quiet road with care, aiming for the brown-and-yellow AVIS sign posted on the other side.

Hiking west on the narrow footpath that leads to the shore of a pond, the realization dawns that Baker’s Meadow is nothing of the kind. In fact it hasn’t been a meadow since muskrat fur turned heads in the 1920s. Noting that there was more money to be made in fashion than in milk or hay, landowner Alexander Henderson built a dam and started a fur farm. Fortunately for all animals involved, the 1929 market crash brought it all to an end, and in 1958 the Henderson family was persuaded to sell their “meadow” to AVIS.

To navigate this part of the hike, follow white markers around the pond’s periphery, being mindful that due to muskrat and beaver work, the pond’s depth and therefore its contour is in constant flux. Between ducking under cherry boughs and lilting birches, cast a glance at the water to catch sight of animal life. Hiking through on a September afternoon, I spotted a family of three wild swans preening in the weedy shallows.

Beyond Henderson’s dam, about 0.2 miles along, the trail bends due west to stay flush to the water’s edge, encountering remnant stone walls as it goes. Crossing a small footbridge on the pond’s far side, the route cuts across a wooded peninsula then weaves through a stone wall keeping close to the water. Nearing houses on Oriole Drive, the trail passes a path on the left then crosses another bridge as it swings back eastward.

Upland banking closes in to the left as the trail eventually winds north passing wetland extending from the pond. In time, the pond retreats from view as the trail enters the heavy shadows of woods and eases along the side of a sharply sloped hill. In spots where water percolates through underfoot, the boardwalk ensures dry crossing. Joining up close to a stone wall on its left, the trail soon makes a final climb to Reservation Road. To finish the hike, step from earth to pavement and bear left to retrace steps to the West Parish Garden Cemetery and parking on Cutler Road.