04 MUDDY RIVER LOOP

KEY AT-A-GLANCE INFORMATION

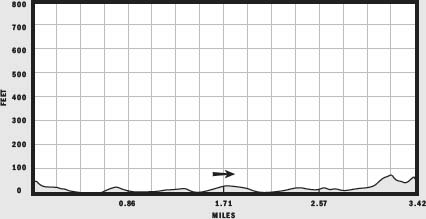

LENGTH: 3.42 miles

CONFIGURATION: 2 linked loops

DIFFICULTY: Easy

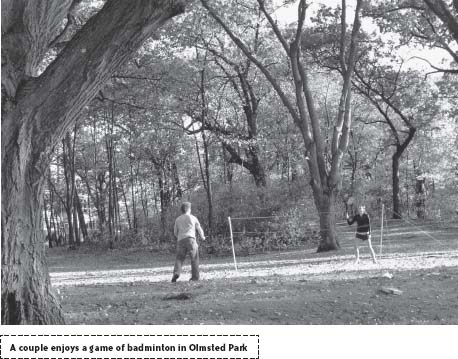

SCENERY: Views along the Muddy River, and of woodland, ponds, and historic architecture

EXPOSURE: Mixed sun and shade

TRAFFIC: Moderate to heavy

TRAIL SURFACE: Clay, turf, and pavement

HIKING TIME: 1.5 hours

SEASON: Year-round, unrestricted

MAPS: Available through the Emerald Necklace Conservancy at 2 Brookline Place, Brookline, 2 blocks west of the park, off Boylston Street (MA 9), www.emeraldnecklace.org

FACILITIES: Restrooms are open to the public during the summer at Jamaica Pond, located adjacent to the Muddy River’s southern end.

SPECIAL COMMENTS: For more information about the Emerald Necklace and Frederick Law Olmsted, stop by the Emerald Necklace Conservancy.

WHEELCHAIR TRAVERSABLE: The entire length of the Muddy River is wheelchair traversable; however, several paths chosen for this hike are not.

DRIVING DISTANCE FROM BOSTON COMMON: 3 miles

Muddy River Loop

UTM Zone (WGS84) 19T

Easting: 325435

Northing: 4687860

Latitude: N 42° 19' 24"

Longitude: W 71° 07' 07"

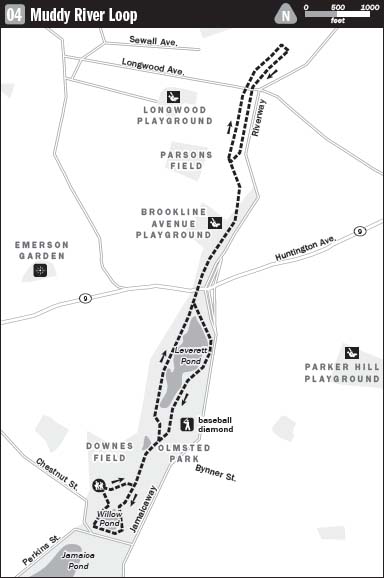

Directions

To reach the parking area on Pond Avenue by car, take the Jamaicaway south to where it intersects with Perkins street. Turn right onto Perkins Street and then right onto Chestnut Street, at the next intersection. Exit the rotary at the first right. The parking lot is immediately to the right on Pond Avenue. The Muddy River parks are easily reached by public transportation via the #39 bus that runs along Huntington Avenue and Center Street in Jamaica Plain or the Longwood train on the MBTA Green line.

IN BRIEF

This hike follows the course of the Muddy River from the edge of Boston’s Back Bay to Jamaica Plain through parkland designed by Frederick Law Olmsted.

DESCRIPTION

In 1881, with the monumental redevelopment of the Back Bay Fens three years along, Frederick Law Olmsted met with Boston’s Board of Commissioners and presented his plan for a series of parks he described as a “green ribbon.” It would take time and many patient conversations with commissioners, engineers, and gardeners, but Olmsted’s vision prevailed. Once completed, the Emerald Necklace would make a 1,100-acre chain from the Boston Common to Franklin Park. The Olmsted plan for the Muddy River improvement won approval and, after a 10-year delay while the city searched for funding, workers hefted shovels and broke ground.

Locate the trailhead at the northeast corner of the parking lot, and hike up the western slope of the drumlin Nickerson Hill to enter woodlands. Reaching a U-junction, bear left and continue north on a path of packed earth and loose stone above the Muddy River, following it down the hill’s softly tapering northern side. At the split ahead, choose the path to the right and make your way past a mix of black oak, sweet gum, and beech to reach Spring Pond, a shallow “natural history pool” of Olmsted’s design.

Surely a favorite spot for many who frequent the park, this shaded pool harbors the southernmost freshwater population of threespine sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus) in the country. If hiking through in spring, try to spot the males of this small species of fish building nests to impress eligible females. In that the Massachusetts Division of Fish and Wildlife lists them as endangered, it is astonishing that threespine sticklebacks live right in the heart of Boston.

Just past Spring Pond, the path crosses a stream that flows from the home of the stickleback to Willow Pond, which lies to the left. Several yards ahead, the path forks as it reaches Willow Pond Road. Opt for the left-hand route and stride across this lightly trafficked road to rejoin the footpath.

After scrambling up the gravel banking on the other side, continue straight on a narrow packed-earth trail to stay within Olmsted’s planted woodlands. Arching over this gentle hill, the trail descends through trees to a path that sweeps east to west. Bear left and continue to a stone bridge built across the southern tip of Leverett Pond.

The far end of the bridge connects to two paths running parallel to one another and to the water; the nearer path is for pedestrians, and the farther one for bicycles. Bear right, following close to the pond’s banking, to pass three small islands just offshore. Created by Olmsted to add visual interest, these peaceful islands are rich with wildlife. Each spring, pairs of Canada geese—likely themselves hatchlings of the islands—assert ownership of nesting sites on this lovely real estate. Despite dangers, including dogs, foxes, coyotes, raccoons, snapping turtles, and humans, a clutch or two of new goslings emerge every year.

This section of the hike—Olmsted Park—ends at the northern bank of Leverett Pond, where MA 9 interrupts the Emerald Necklace. To continue, you must either brave the traffic between lights or cross the busy road by taking the Jamaicaway bridge. If choosing the former, aim for the break in the median strip cut for bicyclists and pick up the worn path beyond the sidewalk opposite.

Flowing unseen below MA 9 (and other roads along its course), the waters of the Muddy River reappear once you are beyond the pavement. Keeping this gurgling brook to the right, continue on River Road past the home of Brookline Ice and Coal and a ramp to the Jamaicaway and travel alongside Brookline Avenue. Using the crosswalk at Aspinwall Avenue, cross Brookline Avenue and Parkway Road to reach another gem of the Emerald Necklace, Riverway Park as the Muddy River continues north towards the Charles River.

A short way in, the path crosses a broad stone bridge arching northward. As the path resumes its course over ground, it is embraced on either side by the river. Below steep bankings, ducks kick up ripples in the shade of beech trees. Olmsted created this and a second thickly planted island to hide the former Boston and Albany Railroad (now the MBTA) and muffle the creaks and clangs of passing trains. A moment later, the lightly used (soon to be closed to cars) Netherlands Road breaks the path. After the interruption, the path approaches Brookline’s Longwood neighborhood. Here Olmsted insulated the park from houses and other aesthetic and sensory disturbances by having earth mounded to the height of a man’s head and planted with ornamental shrubs.

The Longwood neighborhood is rich in history and intrigue in its own right: Judge Sewall—of Salem Witch Trial notoriety—once owned a generous portion of the area; in fact, when Brookline succeeded (after its third attempt) in winning its independence from Boston in 1705, it took its name from that of the Sewall family farm, which bordered the Charles to the north and the Muddy River to the east.

Soon after Uriah Cotting and company built the Roxbury Mill Dam across a tidal estuary between Beacon Hill and Sewall Point (Kenmore Square) in 1821, David Sears II, one of Boston’s wealthiest citizens, seized on what he recognized as a budding opportunity, and promptly began buying low-lying meadowland spread over 500 acres south and west of the Charles River.

In the same year that Cotting began constructing his dam, Napoleon Bonaparte died in exile. To honor Napoleon, or because he shared one or two of the general’s most notable traits, Sears named his neighborhood “Longwood” after the Frenchman’s final home on the island of Sainte-Hélène.

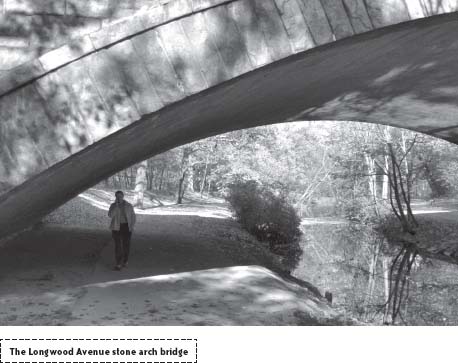

Passing under the Longwood Bridge, designed by Shepley, Rutan, and Coolidge and built in 1898, the path continues along the narrowest section of the park and widens as it reaches a smaller footbridge, the Chapel Street Bridge.

In total, the Muddy River park system includes 17 bridges, each painstakingly designed. It is all but forgotten now, but Olmsted had anything but an easy time getting his bridges built. One complicating factor was that some of the bridges lay on both Boston and Brookline land and were, therefore, joint projects. Another was that Olmsted had to dance a two-step to satisfy conflicting tastes. In keeping with his vision of creating a rustic, naturalistic landscape “slightly refined by art,” Olmsted intended that the bridges be simple structures made of fieldstone. Others, like Charles Sprague Sargent, the director of the Arnold Arboretum, were aggressive in expressing opposing taste. They insisted that the bridges be more finished and ornate—that they include wrought-iron rails and details. The resulting bridges are therefore products of hard-won compromise.

To complete a tour of the park end to end, stay left, following the river’s west bank; otherwise, turn right to hike across the Chapel Street Bridge and, once on the other side, bear right to hike back upriver.

The path runs the entire length of the river’s east side, but because of heavy traffic on the Jamaicaway—a roadway that in Olmsted’s time served horse-drawn vehicles but now serves speeding cars—it is best to return to the river’s quieter west bank once you reach Netherlands Road.

From Netherlands Road, resume the path traveled earlier and retrace your steps to Leverett Pond and Olmsted Park. On returning to the pond, bear left to weave back to the greenway’s east side to vary the view. The clay-surfaced footpath runs flush to the Jamaicaway and Leverett Pond before dipping away from the rushing roadway as the park widens. Ease right at the fork ahead to stay close to the ten-acre pond.

Before the Muddy River Improvement Project was under way, this was not so much a pond as a dense sewage-fouled cattail swamp. Before human tampering, salt water flowing into The Fens from the Charles River eventually mixed with freshwater from springs in Jamaica Pond. In drawing up his plan for the park system, Olmsted somewhat reluctantly decided that The Fens should be a purely saltwater park and that the Muddy River should be strictly freshwater fed. The wetland that became Leverett Pond was dammed, dredged, and finally contoured to a shape drawn by Olmsted. To make sure the pond was kept well fed, another wholly separate brook was diverted to it from Brookline.

Nine acres of hand-planted hardwood trees help make the city disappear again as the path passes alongside Leverett Woods. Continuing south to skirt a baseball diamond at Daisy Field, the path soon encounters Willow Road. Once across, pick up the footpath that travels between Willow Pond and the Stickleback pool, and bear right at the first fork to switch to a path not yet taken. Continuing south through a landscape designed by the Wisconsin Glacier and left all but untouched by Olmsted, take the second left to connect with a path shooting up Nickerson Hill.

After pausing at the fine vantage point of this stony knuckle, head down the hill’s south side and take the path below clockwise around Ward’s Pond. Left wild by Olmsted, this kettle hole harbors all sorts of wildlife, including birds, amphibians, and such fish as bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus), largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), and pumpkinseed (Lepomis gibbosus). After jumping the stream on the pond’s northwest side, take the first path to the left to return to the parking lot.

NEARBY ATTRACTIONS

Both Brookline and Jamaica Plain offer a great assortment of restaurants, many within walking distance. If you have a hankering for coffee or ice cream, visit J. P. Licks (659 Center Street, Jamaica Plain). For a hearty, wholesome, and affordable brunch, lunch, or dinner try Center Street Café (669A Center Street, Jamaica Plain). For more exotic fare visit Bukhara (701 Center Street, Jamaica Plain) for its wonderful Indian cuisine, or J. P. Seafood (730 Center Street, Jamaica Plain) which serves excellent sushi and a full menu besides. Located at 7 Station Street across from the Brookline Village MBTA (subway) stop, Kookoo’s Café serves up tasty robust coffee, a fine collection of teas, highly delectable sweets, homemade soups, sandwiches, and lunch dishes with a distinctly Persian touch. On Washington Street half a block away, Restaurant Stoli (213 Washington Street) and Café St. Petersburg (236 Washington Street) entice with authentic Russian entrées.