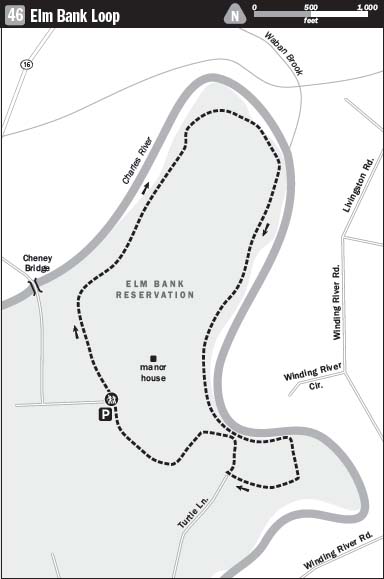

46 ELM BANK LOOP

KEY AT-A-GLANCE INFORMATION

LENGTH: 1.86 miles

CONFIGURATION: Loop

DIFFICULTY: Easy

SCENERY: View of the Charles River as it flows beside diverse woods

EXPOSURE: Mostly shaded

TRAFFIC: Moderate

TRAIL SURFACE: Packed earth

HIKING TIME: 45 minutes–1 hour

SEASON: Year-round dawn–dusk

ACCESS: Free

MAPS: Posted at the entrance, also available at www.mass.gov/dcr/parks/metroboston/maps/elmbank.gif

FACILITIES: Restrooms available at the Metropolitan District Commission (MDC) Ranger headquarters; soccer fields; canoe/kayak launch

SPECIAL COMMENTS: The Massachusetts Horticultural Society is headquartered here. Visitors can tour the society’s demonstration gardens and the Elm Bank Estate.

WHEELCHAIR TRAVERSABLE: Much of the grounds of the Elm Bank estate are wheelchair traversable; however, depending on condition, several sections of the hike described are not.

DRIVING DISTANCE TO BOSTON COMMON: 15 miles

Elm Bank Loop

UTM Zone (WGS84) 19T

Easting: 310074

Northing: 4682871

Latitude: N 42° 16' 30"

Longitude: W 71° 18' 12"

Directions

From Boston, take the Massachusetts Turnpike (I-90 west) to Exit 14 (Weston). Follow I-95 (MA 128 south) to Exit 21B (MA 16 west). Follow MA 16 west 2.9 miles. On MA 16 west you will come to a stoplight (at a five-way intersection) in the town of Wellesley where you will bear left to continue 1.7 miles on MA 16. The Elm Bank Horticultural Center will be on your left, marked by a small green sign. The street address is 900 Washington Street (MA 16).

IN BRIEF

Located in an area that has maintained a charmingly rural character despite its proximity to Boston, Elm Bank’s well-tended acres offer miles of hiking both along the wooded banks of the Charles River and over landscaped grounds.

DESCRIPTION

A private estate from the 17th century until the dawn of World War II, Elm Bank was given its name by one of its earliest owners, Colonel John Jones, who planted elm trees along the banks of the Charles River. The property passed through the hands of three more owners before Benjamin Pierce Cheney, a founder of a delivery company now known as American Express, purchased it for $10,000. After Cheney’s death, his daughter Alice and her husband, Dr. William Hewson Baltzell, took over ownership of the estate. Together they built the neo-Georgian manor that still stands on the premises. To accent the elegant architecture, they hired the Olmsted Brothers landscape architectural company to restore and design the grounds and formal gardens. Once settled, the Cheney-Baltzells threw grand parties that spilled from the house into the gardens and to the river beyond.

Reaching her old age, Alice Cheney-Baltzell wrote in her will that upon her death Elm Bank was to be left to her nephew, but if he did not want it, the property should be offered to Wellesley College, and if the college did not want it, the land should be turned over to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Amazingly, each party declined, and Dartmouth College, Benjamin Pierce Cheney’s alma mater, became the beneficiary when the school accepted the estate for $40,000.

Today, Elm Bank’s acres, somewhat reduced in number, are owned by one of the entities that first refused them—the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Thirty-two years after Alice’s death, the state seized a second opportunity to take possession of the property and purchased it. In 1999, the Massachusetts Horticultural Society arranged to lease the buildings and gardens and made Elm Bank their new headquarters.

Starting at the parking lot located beside the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, follow the paved road northwest. As the road curves gently downhill, you will pass the Horticultural Society’s demonstration gardens on the left and the red brick Hunnewell Building on your right. A short distance farther, the road makes a “T.” Cross here to find the trailhead marked by a posted map.

The trail sets off immediately into magnificent woods made all the more impressive by a row of enormous white pines. Flowing northeast 21 miles from its source in Hopkinton, the Charles River lies to the left, just a few feet from the edge of the trail and down a steep slope. In May, after two weeks of record rainfall, the river ran full and faster than normal the day of my hike. According to the Charles River Watershed Association, the river’s rich tea color is normal, no matter the month or recent weather. Leaves, wetland grasses, and debris from other natural sources tint the water with their tannins. Years of concerted efforts to stop dumping and other contamination have borne exciting results. Today 74 percent of the 80-mile river is clean enough for swimming.

The broad trail, cushioned with a soft layer of pine needles, continues atop the river’s right bank. Before too long, the trail descends to just a few feet above water level. You encounter a narrower path splitting off to the right here. Stay with the river route to the left at this break and at each of the next intersections you come to.

Just ahead, the trail arrives at broad opening suitable for a canoe or kayak landing. On the opposite side of the trail, a few feet farther on, is a large vernal pool well fed from river overflow. Here beech and birch add lightness to the woods that earlier had been dominated by more-somber hemlocks and pines. Charged with energy from a good spring soaking followed by sunny days, the beech leaves virtually glow.

The river bends abruptly southeast at this point, creating a deep oxbow as it changes course to flow first south and then southwest. The bend is so sudden and tight that it is no wonder that, after the winter thaw and healthy rains, the engorged river redraws the map. On the day of my hike, the trail disappeared under a foot of water for a good 100 feet at the top of the oxbow. A passing jogger, momentarily befuddled, remarked that she had never before seen the trail fully flooded.

Happy to take our shoes off and wet our feet, my companion and I took our chances and stayed with the trail. Halfway across, I needed to roll my pants legs up closer to my knees, but the water, far warmer than expected, felt wonderful.

Looking across the river once back on dry land, you can spot private houses through the budding trees in May. By June, they will be hidden. Docks with Adirondack chairs extend onto the water from two homes.

Having experienced limited cutting since the 1700s, the woods along the river are remarkably diverse. Along with species of oaks and pines, there are some tulip trees, hackberry, silver maples, and ashes, and even one towering lilac.

Once the trail has veered decidedly southwest, you will encounter a fork. Both routes lead back to the playing fields at the Elm Bank mansion. On my hike, I chose the right-hand route. This path makes a hairpin turn back to the river, heading north before turning west at another split. On this last stretch, the trail is recessed below the level of the dense woods. Mature trees cast shadows from far overhead.

Shortly the trail meets another packed-earth trail coming in from the left; stay to the right. Not much farther beyond this, the trail reaches a paved road. On the other side, you will see the playing fields. Cross here and walk to the right to arrive back at the Horticultural Society’s parking lot.