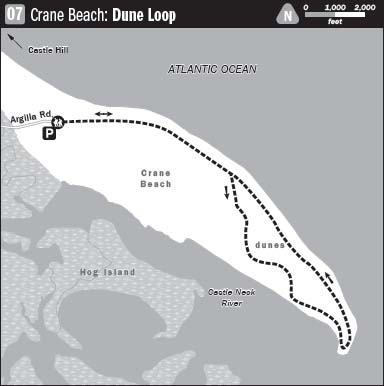

07 CRANE BEACH: Dune Loop

KEY AT-A-GLANCE INFORMATION

LENGTH: 6 miles

CONFIGURATION: Out-and-back with loop

DIFFICULTY: Moderate

SCENERY: Miles of pristine beach, dunes, and views of Plum Island, Cape Ann, and acres of salt marsh

EXPOSURE: Full sun

TRAFFIC: Light to moderate

TRAIL SURFACE: Beach sand

HIKING TIME: 3 hours

SEASON: Year-round sunrise–sunset

ACCESS: Memorial Day–October 1 parking is $15 per car weekdays, $22 weekends, or half price after 3 p.m. Those with a family-level membership of Trustees of Reservations are charged a reduced rate. A fuel- and cost-saving, car-free alternative is to take the commuter line to Ipswich and then the Ipswich/Essex Explorer shuttle bus to Crane Beach. Visit www.ipswich-essexexplorer.com.

MAPS: Posted on trails, but some are difficult to read

FACILITIES: Restrooms and snack bar open Memorial Day–Labor Day; only outhouses open in off-season

SPECIAL COMMENTS: Leashed dogs permitted October 1–March 31 but are restricted to below high-tide line.

WHEELCHAIR TRAVERSABLE: No

DRIVING DISTANCE FROM BOSTON COMMON: 31 miles

Crane Beach: Dune Loop

UTM Zone (WGS84) 19T

Easting: 355341

Northing: 4727302

Latitude: N 42° 41' 03"

Longitude: W 70° 45' 57"

Directions

From MA 128 north (toward Gloucester), take Exit 20A (US 1A north) and follow it 8 miles to Ipswich. Turn right onto MA 133 east and follow it 1.5 miles. Turn left onto Northgate Road and follow it 0.5 miles. Turn right onto Argilla Road and follow that 2.5 miles to Crane Beach gatehouse at the end of the paved road.

IN BRIEF

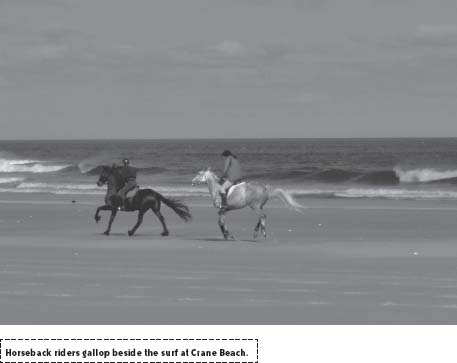

On this hike—best done barefoot—you will follow lapping waves along the length of one of Massachusetts’s most immaculate beaches. Approaching the marshes of Essex and the granite-littered coast of Gloucester, you will cross the high dunes of the inner beach, and upon reaching the peninsula’s tip, hike ocean-side back to the start.

DESCRIPTION

In 1908, amidst a lively rumor that the brother of President Taft had bought “Castle Hill Farm” from the estate of the recently deceased Chicago railroad tycoon John Burnham Brown, the Crane Plumbing heir Richard T. Crane Jr. slunk in and bought the property outright with pocket cash. Or so it seemed. Regardless of the circumstances, the 36-year-old Richard T. Crane took possession of the 250 acres made up of bald drumlins and picturesque meadows flush to salt marsh for $125,000. Not one to stand still while the grass grew beneath his feet, Crane set to work building the first of his mansions at the crest of Castle Hill. By the first spring, the 65-room Italianate house was ready for habitation, its grounds reconfigured and primped by none other than the landscape design firm of Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. In 1925, no longer enamored of the house, Crane had it demolished and replaced by the smaller but no less grand Georgian-style mansion that still looks down from the hill today.

Upon settling in, Crane soon fancied owning all that surrounded him. And so, turning desire to action, he bought up Wigwam, Sagamore, and Caverly Hills; Woodbury’s Landing opposite Hog Island; both Hog Island and Patterson’s Islands; and another farm across the creek. The sum total amounted to about 3,500 acres.

Miffed that the 5-mile Great Neck Beach had passed into Crane’s hands with no review by the selectman, despite the town’s claim of perpetual ownership, locals were not quiet about their resentment. But with an ear cocked, Crane heard their murmuring and responded affably by inviting the entire Ipswich school population of 900 to his son Cornelius’s birthday party. Henceforth the outing became an annual event, and as time passed, people accepted Crane’s ownership and gradually referred to the beach simply as “Crane’s.”

In 1945, fourteen years after her husband’s death on his 58th birthday, Florence Crane gave 1,000 acres, including most of Crane’s Beach and Castle Neck, to the Trustees of Reservations. When she died only four years later, she bequeathed also the “Great House” and an additional 300 surrounding acres.

From the out-of-town visitor parking lot to the right of the entrance, take the southernmost boardwalk to the beach. If it is a warm, clear day, you will want to free your feet from your shoes and socks, sink your toes in the sand, and feed your eyes on the Prussian blue sea before diverting your attention back to land.

When the air is particularly dry and particle free, you can see as far north as Maine’s Mount Adamenticus. The Isles of Shoals lying off the coast of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, may also be visible as dark slivers on the horizon. On most days absent of heavy weather, Newburyport’s Plum Island is visible stretching close to Ipswich’s now thickly populated Great Neck and Little Neck, located on the left, opposite the mouth of Foxcreek and the toilet tycoon Cornelius Crane’s grand estate at Castle Hill.

On a beach as beautiful and appealing to the senses as Crane’s, to wander directionless, willy-nilly as your spirit wills, makes more sense than following a prescribed route. This hike therefore invites—even assumes—improvisation as it leads from the water-lapped tide line to the deep sands of Crane’s highest inner dunes and back.

Having stretched driving muscles and exposed your pent-up thoughts to the robust winds ever reconfiguring the ground you stand on, turn to the right and lay footprints eastward. Though New England’s beach season is understood to run from the first day of summer through Labor Day, a good many natives of towns such as Ipswich know that the beach is at its most sublime in the autumn and is certainly at its most dramatic during the frozen winter months. Swimmers should note that, though warmer than Plum Island, the water at Crane’s Beach numbs limbs all months of the year but is tolerable in August, particularly at low tide, after sizzling sands have passed the sun’s energy onto the retreating sea.

If the tide is high or rising fast, the path will lead across loose, finely ground granite sand sparkling with mica. In places, veins of feldspar color the sand a hard, heat-absorbing purple. Wriggle your heals in as you walk through these spots to make the beach squeak or “sing.” At low tide, chances are the lively waves and the piping plovers sprinting between them on blurred spindle legs will lure you to the glistening packed sand in the intertidal zone.

Crane’s is one of just three locations in North America where piping plovers are known to rear young. Reliant on undisturbed beaches, piping plovers lay their eggs directly on the sand in abbreviated nests. Where their traditional nesting grounds have been compromised by development and other human activity, breeding pairs have been known to try their luck in paved parking lots. Consequently, these small birds that subsist on aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates are several flittering heartbeats away from extinction. For this reason, the Trustees of Reservations ask beach visitors to help them protect their resident plovers by staying out of sensitive nesting areas.

Crane’s, like any beach or natural coastal area, is highly plastic. Hurricane forces and each gentle afternoon breeze act to reshape the beach’s contours. Generations ago, dunes cast deep shadows all along the peninsula from one end to the other. Today, the beach sands lie flatter, spreading to the east like the palm of a great, submerged hand. When gravitational forces tip the water toward Asia twice a day, pools form, adding exciting alterations to the beachscape. Crosscurrents furrow these flats in a wet, sandy corduroy, concealing razor clams and the beefier bivalve—the sea clam.

Should a stiff wind, the sight of a kite, or a like distraction bid you to turn and walk backward across this stretch, a half mile on you will find the Crane Castle hidden behind a bend. Looking ahead, you will see Cape Ann against the horizon. Following a trajectory of your own choosing, look to the dunes gaining in magnitude to the right and you will find a passage to the inner beach. Until this point, wire fencing restricts foot traffic to the seaweed-laced high-water mark and sands lying to the east.

Turn here and follow this wide, wire avenue westward into the muffled sands beyond. Knife-sharp blades of beach grass fall in wind-tussled waves over the banks alongside. Without this grass and its binding roots, there would be no dunes.

The trail’s grade steepens to crest a dune several hundred feet in. Striding, half sliding, down the other side, you come to a level junction. Bear left to take the yellow trail south. Insulated by sand granules piled to great depths, the air in the still valleys is warmer and softer than the biting salt air blowing off the sea. In this unique microclimate, intriguing plants take root. Mushrooms—that when dry burst into star shapes—dot the trail amid bayberry bushes.

After winding along the rim of a bog lying to the right, the trail serpentines southeastward funneling through dune clefts before climbing to a sandy pinnacle overlooking the beach’s southernmost tip. Pause here to survey Gloucester’s Wingarsheek Beach on the opposite shore, the channel waters flowing past Conomo Point to Essex Harbor, and the uplands surrounding the Crane family’s Great House to the northwest.

Continue following numbered yellow trail markers as they lead across Castle Neck and deliver you to a spot directly across from Choate, or Hog Island, as it is informally known. This beautiful island with a humble name has the distinction of being the birthplace of Senator Rufus Choate, the burial place of Cornelius Crane, and the setting for much of Nicholas Hytner’s film Crucible.

This stretch of beach on a secluded cove receives more visitors by boat than by foot, and few at that. Occasionally, harbor seals swim ashore here to enjoy some sun or respite from life at sea. In certain months, vast numbers of romantically minded horseshoe crabs mingle in the shallow waters looking like armored military vehicles on reconnaissance.

Leave the yellow trail and make your own track southeast along the neck’s thin fringe of beach. On the mild October afternoon I hiked these sands, game monarch butterflies fluttered northward, crossing the channel against a stiff breeze. Considering the size of their motors concocted of milkweed and hocuspocus within cocoons, their quest to reach the dunes 100 yards beyond seemed disastrously quixotic. But milkweed, goldenrod, tansy, and asters must generate energy beyond the wildest dreams of oilmen, for these fire-colored bugs were achieving the impossible. Tossed in all directions by heartless gusts, they fluttered onward, making headway like battened-down beetle cats sailing seaward into heavy weather.

As you round the peninsula’s tip, the wind will catch you at a different angle. Heading west with hair clutching at your face or blown straight out behind you, you’ll see the beach broaden again. Catty-corner to Gloucester’s Halibut Point, mixed flocks of gulls congregate where a foamy seam marks a crosscurrent. Soon, bending northwest, Plum Island comes into view, followed by the cottages and the water tower on Great Neck, and finally Crane’s Castle nestled regally on its hill. Cut back into the loose sand of the seaweed-strewn upland to find the first of the two boardwalks when fading light, foul weather, or a growling stomach sends you back to your car.

NEARBY ATTRACTIONS

Any trip to Crane Beach should include a stop at Russells Orchard (phone [978] 356-5366), located enroute to the beach at 143 Argilla Road. From April 28 through November 25, this family-run business sells fresh fruits, vegetables, baked goods (including scrumptious cider donuts and delectable pies), hot and cold beverages, and fine fruit wines made on site. Between sips of coffee and tasty bites, there is plenty more to tempt or distract you, including a selection of books by local authors, potted perennials, pumpkins, and friendly farm animals.

Those looking for a hearty meal of local seafood might like to try one of the many restaurants located on MA 133 between Ipswich and Essex. To reach MA 133 from Crane Beach drive approximately 0.5 miles on Argilla Road, bear left onto Northgate Road, and continue to the end. At the intersection of Northgate Road and MA 133, turn left and continue 3 miles to Main Street in Essex.

If you trust local opinion, go no farther than Village Restaurant, located at 55 Main Street. Village Restaurant is open Tuesday through Sunday, 11:30 until 8 p.m., 9 p.m. on Friday and Saturday; call (978) 768-6400 for more information.