08 HALIBUT POINT: Quarry Loop

KEY AT-A-GLANCE INFORMATION

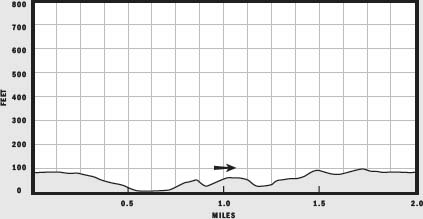

LENGTH: 2 miles

CONFIGURATION: Loop

DIFFICULTY: Moderate

SCENERY: Views of granite quarries and the magnificent Cape Ann coast

EXPOSURE: Mostly sunny; some shaded areas

TRAFFIC: Moderate

TRAIL SURFACE: Packed earth leading to the coast, and great granite boulders along the tidal zone

HIKING TIME: 1.5 hours, depending on weather conditions

SEASON: year-round 8 a.m.–sunset

ACCESS: Parking $2

MAPS: Available at visitor center and at the ranger’s booth at the entrance to the parking lot

FACILITIES: Restrooms and picnic tables

SPECIAL COMMENTS: Halibut Point is an excellent spot for bird-watching. In 1997, a renewable-energy demonstration center was constructed on site.

WHEELCHAIR TRAVERSABLE: The paths to the visitor center and to the main quarry are wheelchair accessible.

DRIVING DISTANCE FROM BOSTON COMMON: 32 miles

Halibut Point: Quarry Loop

UTM Zone (WGS84) 19T

Easting: 366357

Northing: 4727311

Latitude: N 42° 41' 12"

Longitude: W 70° 37' 53"

Directions

From Boston, take MA 128 north toward Gloucester. At the first traffic circle, go three quarters of the way around and take MA 127 toward Pigeon Cove. Continue 5 miles, passing through the villages of Annesquam and Lanesville. The parking lot is 1 mile into Lanesville on Gott Avenue, across from the Old Farm Inn.

IN BRIEF

Shaped by geologic forces, glacial ice sheets, the chisels and sweat of quarrymen, and crashing waves off the Atlantic, Halibut Point is as variable as the weather. On warm summer days this knuckle of granite facing the sea offers a pleasant place to sunbathe and picnic. In less benign seasons the point is a terrific place to watch nature flex its muscles.

DESCRIPTION

Legend has it that the first house built on Rockport’s hardscrabble turf was erected around the bend from Halibut Point in 1692. As told by authors Copeland and Rogers in their book The Saga of Cape Ann, the “Old House,” as it is known locally, was built by two young men from Salem for their mother, who had been condemned at the Salem Witch Trials. Spared death because she was pregnant, the woman was expelled from the community and exiled to the wilderness of Cape Ann. Bears, wolves, and Agawam Indians accented the landscape, along with a handful of hunting shanties built by settlers of Ipswich.

In The Town on Sandy Bay: A History of Rockport, Marshall W. S. Swan writes that until 1840 when it was incorporated as an independent town, the vast acreage that is now Rockport was nothing more than commons land to Gloucester’s settlers. Its woods and open fields were forage ground for dry milk cows, oxen on the dole, and horses unfit for harness or saddle. In time, however, the voting citizenry decided that all the land from Lane’s Cove to Sandy Bay—as Rockport was first known—should be apportioned to qualified taxpaying householders born in Gloucester who were 21 years of age or older.

One qualifying beneficiary was John Babson, who was provided land to establish a fishing station southeast of Halibut Point at Gap Head. Soon after building himself a cabin at the spot, Babson discovered a bear living nearby. Uninterested in fostering a commensal relationship with the animal, Babson put an end to the bear with a hunting knife, skinned it, and strung its hide over a rock by the sea to dry. Passing fishermen caught sight of the bear’s shaggy remains and henceforth referred to the rough spit of land as “Bearskin Neck.”

The craggy coast north of Gloucester’s Sandy Bay grew slowly through the 1700s. Characterized by thin soil rich in little besides granite and tiny harbors exposed to violent seas, the land lent itself to few lucrative enterprises. And yet Rockport’s first families, the Tarrs, the Pools, and the Babsons, hung on and multiplied.

Driven from Saco, Maine, by warring natives, Richard Tarr moved his young wife and two sons from temporary safe haven in Marblehead to Cape Ann in 1695. A lumberman by trade, Tarr saw opportunity in the cape’s thickly forested land. John Pool shared Tarr’s vision and relocated his family to Sandy Bay from Beverly to establish the first sawmill. Together, they and others helped supply the boatloads of hemlock needed for wharf building in Boston.

As the trees dwindled, the fishing industry began to take hold and the shipping trade expanded. But the Revolutionary War, and the War of 1812, severely dampened the commercial vitality of Cape Ann. Many fishing boats were sunk and trade ships shackled, seized, or destroyed during these conflicts.

In the mid-1800s, Nehemiah Knowlton, another of Gloucester’s enterprising men, introduced a new industry to Cape Ann—stone quarrying. Upon noting the success of Quincy’s quarries, Knowlton took a chance and cut 500 tons of granite at Pigeon Cove and advertised it for sale in a Boston newspaper.

By 1860, the cape’s quarries employed 450 workers, and 100 more manned the sloops that ferried the granite to ports as far away as San Francisco, Cuba, and South America.

The Chain Link Bridge that spans the Merrimac River near Maudslay State Park in Newburyport is constructed of Cape Ann granite, as is Boston’s Post Office Building and Longfellow Bridge.

For nearly a century, men equipped first with hand tools and eventually steam-powered tools and dynamite cut stone from Babson Farm Quarry at Halibut Point. It was the crash of 1929 and the emergence of concrete that finally closed the industry down.

Cross Gott Avenue at the northwest corner of the parking lot to pick up a wooded path to the visitor center. Halfway along, you will pass two small quarries, with narrow trails leading to them to the right. Filled with rainwater and well camouflaged by vines and scrub, these excavations leave a great deal to the imagination. Not so the enormous quarry at trail’s end.

Arriving at a broad T–intersection—you will feel the rush of bracing air and catch a view of the sea. Shifting your focus from the distant waves to the foreground, you will find an enormous water-filled cavity before you. Herring gulls and ducks now bob on thin ripples raised by wind gusting across this old work site where, men cut great slabs of rock, producing this enormous void.

Take the trail to the left to find the visitor center, or continue walking along the edge of the quarry on the gravel path past sparse woods of cherry, sumac, and blackberries. Markers along the quarry coordinate with a self-guided tour.

Heading northeast, you pass the quarry to your left as you turn toward the ocean. After walking a short distance downhill, you will find a narrow, packed-earth path leading off to the right. Leave the gravel trail and pick up this new path traveling northeast. At the next fork, take the right-hand path to continue eastward.

Close to the shore now, you will see wild beach roses which, when blooming in the heat of summer, give off a heady scent—stronger than that of any cultivated counterpart. Stay to the right at each of the next splits to reach the easternmost end of the reservation. At the border, the trail turns toward the sea. Here you will come to a sign that reads “Sea Rocks this way.”

“Sea Rocks” refers to the enormous boulders lying along the shoreline of Halibut Point. Consisting of sheets of granite mixed with irregular orbs tossed into heaps by quarrymen and the thunderous surf, Sea Rocks offers a dramatic setting for picnicking, tanning, surf-casting, tidal-pool gazing, and especially rock hopping. If your inclination is to do nothing at all, there is always plenty to watch, from day-sailors tacking off the point to migrating birds and spectacular weather in all seasons.

To continue your hike, make your way northwest, keeping the breaking waves to your right. No walk along here is ever the same since the tide level determines one’s route, length of one’s stride and one’s ability or inclination to leap across chasms. Beware of low tide, when kelp and sea moss clinging to rocks make for treacherous footing.

Looking ahead, you will see a mountain of granite blocks tapering steeply to the sea. Walk or rock-hop to the base of this granite behemoth for a good look to appreciate the hours of sweat and muscle strain represented by this pile of castoffs. Though forces of nature have reshaped the pile, it was quarrymen who heaved the stone here.

Once you have taken in this impressive sight backtrack to a broad sandy trail leading off to the right. The trailhead is not formally marked, but a sign warning of the dangers of swimming off the point alerts you to the turn, as does the miniature Stonehenge just inside the bend. Impromptu artists have arranged palm-sized quarry remnants into intriguing sculptures in a sandy enclosure just off the path.

Follow the gravel trail back uphill, and once at the top, bear right to walk to the lookout on the peak of the mountain of quarry debris. From this point, on a clear day, it is possible to see as far north as Maine’s Mount Agamenticus, and in the nearer distance, Plum Island of Newburyport.

Leaving the peak, walk back toward the visitor center and the lighthouse. To tour the grounds, turn right and follow the wide path westward past birch, sumac, and cedar trees. A short way farther, turn onto the Bayview Trail to head back toward the sea. This trail descends steeply then rises again as it curves westward. Looking up, you’re likely to see a flock of cormorants fly by, traveling from rookery to fishing grounds.

Curving back uphill, the Bayview Trail loops southwest past a grassy overlook. A small trail to the right leads to another lookout. Returning to the Bayview Trail, follow it to its end, then continue straight ahead on a wide gravel path.

Look for a sign for the Back 40 Loop, and take this grassy route westward, walking downhill before swinging left to head south once more on this peaceful “lane.”

Closing the loop, you find yourself back at the clearing where you began. From this junction, continue straight to join the trail that leads to the rear of the visitor center. Keep left to pass in front of the visitor center and rejoin the path that leads back to the parking lot.