09 PLUM ISLAND: Hellcat Trail

KEY AT-A-GLANCE INFORMATION

LENGTH: 1.84 miles

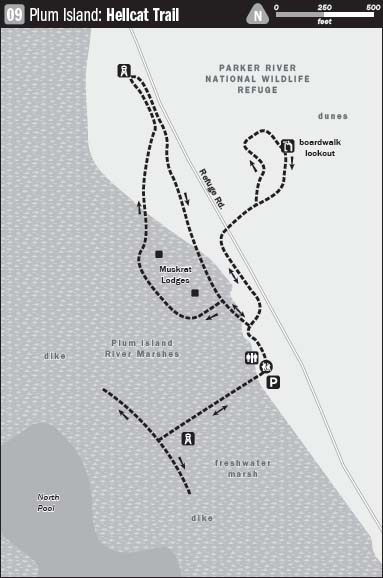

CONFIGURATION: Double loop

DIFFICULTY: Easy to moderate

SCENERY: Salt marsh, the inner beach, sand dunes, and the Atlantic Ocean

EXPOSURE: Equal parts sun and shade

TRAFFIC: Moderate

TRAIL SURFACE: Packed earth

HIKING TIME: 30–45 minutes

SEASON: Year-round sunrise–sunset

ACCESS: The daily entrance fee is $5 per car, $2 for people on foot or bicycle.

MAPS: Available at the Parker River National Wildlife Refuge headquarters and visitor center (6 Plum Island Turnpike, Newburyport, MA 01950), at the gatehouse, and at the trailhead, while supplies last.

FACILITIES AND COMMENTS: See longer note at end of description.

WHEELCHAIR TRAVERSABLE: A small section of trail located off the southernmost parking area (7) is specially designed for wheelchair users. In addition, Pines Trail (located at parking area 5) and many of the wildlife-observation areas are wheelchair accessible.

DRIVING DISTANCE FROM BOSTON COMMON: 38 miles

Plum Island: Hellcat Trail

UTM Zone (WGS84) 19T

Easting: 353028

Northing: 4733673

Latitude: N 42° 44' 29"

Longitude: W 70° 47' 44"

Directions

From Boston, take Storrow Drive East, following signs for US 1 north. Merge onto US 1 north toward Tobin Bridge/Revere. At 15.1 miles, merge onto I-95 north. From I-95, take Exit 57 and travel east on MA 113 to MA 1A south to the intersection with Rolfe’s Lane; continue 0.5 miles to its end. Turn right onto Plum Island Turnpike and travel 2 miles, crossing Sergeant Donald Wilkinson Bridge to Plum Island. Take the first right onto Sunset Drive and travel 0.5 miles to the refuge entrance. Continue 3.5 miles to the Hellcat Wildlife Observation area on the left.

IN BRIEF

This hike explores a once all but impenetrable swamp and night heron colony located at the midway point of Plum Island. Traveling over an elevated boardwalk, the hike surveys the freshwater marsh of the Parker River Wildlife Refuge, passes through Plum Island’s inner beach, then crests enormous dunes to reach a lookout over the Atlantic Ocean.

DESCRIPTION

In days long gone, there was not a more remote and forbidding place on Plum Island than Hellcat Swamp. Marm Small harvested cranberries and provided board to “Gundalow men,” (those who shuttled salt hay from the marsh to Newbury’s Old Town on flat-bottom barges) at Halfway Farm located just across the mouth of the Parker River; and duck hunters set up camps farther south at a beach in a cove called The Knobbs—but few passed through the swamp that lies between.

Tides, terrain, and weather have long conspired to make the center of the island inaccessible at best and deadly at worst. Newburyport’s town records document more than one unfortunate episode involving Plum Island’s marshes and beach. One such story is that of Richard Jackman and his young son who, in the winter of 1798, made a trip to the island for wood and, on heading for home the following day, succumbed to the elements after being forced from their boat and trying to continue on foot.

Before 1942, when Audubon turned over its Annie H. Brown Wildlife Sanctuary to the federal government, allowing it to become part of the Parker River National Wildlife Refuge, there was no way of reaching Hellcat Swamp other than by boat or by foot. After acquiring the land, the government constructed the access road that now runs the entire length of the island. Tragically, in building the road workers inadvertently destroyed an enormous black-crowned night heron rookery at Hellcat Swamp.

Today, thanks to an elevated boardwalk, it is possible for nearly everyone to venture into the farthest reaches of the swamp and the inner beach that insulates the swamp from the sea.

Begin at the trailhead located north of the parking lot beside the path that leads northwest to a wildlife lookout tower. Step up onto the boardwalk and follow it south through bayberry bushes to a junction where the trail divides in two. To start the hike with a tour of Plum Island’s dunes, bear right and continue east.

Ahead, where the boardwalk bends north to cross the island, the trail passes through woodland where black oak and red maples grow in an oasis created by the weather-shielding dunes and marsh. Farther along, the boardwalk reaches an area where freshwater vernal pools form when hard-hitting storms bore craters in the sand. As sources of rain fed fresh water, these pools are critical to the island’s mammals and the amphibians that inhabit them.

After bearing east once more, the trail is bisected by the access road. Cross carefully, then take up the boardwalk again as it climbs into the beach’s back dunes. Little besides tenacious black cherry trees (Prunus serotina) and cedars grow here.

In the interest of observing the island’s distinct ecological zones in the sequence in which they were formed, continue left at the split beyond the road. As the trail emerges from the shelter of the inner dunes and proceeds through the more exposed territory of secondary dunes, botanical changes become apparent. Where fierce wind and salt spray are able to penetrate, only specially adapted plants such as beach heather (Hudsonia tomentosa) manage to survive. They, in turn, function to stabilize the ever-shifting sands by holding the dunes with a netting of dense roots. On the western slopes of the next dunes, bayberries and beach plums (Prunus maritima) grow in sheltered niches.

An incongruous stand of black pine (Pinus nigra) adds a thick wedge of trees ahead to the northeast. Native to Austria and other parts of Europe where conditions approximate the austerity of a New England beach, these trees were planted as part of a dune-stabilization effort in 1953. Although the black pine took hold successfully, the project was of dubious merit. What scientists understand now but didn’t then is that barrier islands quell forces—such as hurricane winds—by deadening them with the drag of sand and waterlogged marsh peat. Tampering with this natural system does nothing but impair its performance.

Bearing right at a memorial to conservationist Ludlow Griscom, the trail travels eastward, crossing a lull in the rolling dunes where breeze-blurred footprints of small animals mark the sand among tufts of heather. The Joppa Flats and the Merrimack River are visible to the left across a landscape dominated by sky. Sound-swallowing walls of sand block sight of all but a sliver of Prussianblue Atlantic to the east.

Sloping uphill toward primary dunes that sit like sand-castle replicas of Everest beside the ocean, the trail scales neat sets of stairs to reach a final climb to a lookout constructed behind one last great dune. On a clear day, Cape Ann takes the form of a solid purple-brown bar on the eastern horizon. To the right, the pale band of Crane Beach stretches south to Essex.

From the lookout, the trail descends steep stairs as it retreats back under tree cover on its return southwest. After recrossing the access road, retrace steps over the boardwalk to the trail’s initial fork, and this time bear right onto the Marsh trail.

Where the trail splits a short way in, follow it left as it departs high ground dense with bayberry and beach plum for open marsh thick with cattails.

Though once part of the Great Salt Marsh stretching up the Parker River and beyond, the freshwater marsh immediately surrounding Hellcat Swamp is man-made. In the 1940s and 1950s, the Fish and Wildlife Service created the marsh to aid the recovery of populations of waterfowl species and other native and migratory birds. By building an enormous dike around it, they cut the marsh off from the sea’s tidal currents.

Elevated about three feet above the floodplain of the marsh, the boardwalk bears west then eases north to circle territory claimed by two families of muskrats. The tops of their lodges of woven reed stalks rise a foot or so above the pool.

In winter months all is quiet except for the eerie sounds of the wind whistling through weather-bleached reed stalks, and a marsh hawk’s occasional call. But as early as March, migratory birds arrive and fills the silence with a symphony of honks, screeches, and chirps. Upward of 350 species have been sighted on the island, and Hellcat Swamp is a favorite viewing location. Purple martins arrive in mid-April as do hundreds of American kestrels, sharp-shinned hawks, and other raptor species. Come the waning days of spring, waves of warblers, thrushes, vireos, fly-catchers, and other songbirds arrive and settle to rejuvenate and nest.

After arching out to a lookout station that provides a view over the northern freshwater pool and the town of Newbury beyond, the trail aims east and returns to high ground. Upon reaching a junction, bear left to access a wildlife lookout.

Returning by the same path, bear left at the next fork in the boardwalk and continue south through the shrub land that borders the marsh. Sharp white birches lean into the breeze above an otherwise tangled thicket. In August ripening beach plums add a fruity scent to the air, mixing with the smells of salt water and sunscreen. Continue straight at the next fork then bear right at the last to arrive back at the trailhead.

Extend the hike by following the trail to the right of Hellcat Trail to a lookout tower positioned beside the dike and the freshwater pools.

Note about facilities: There are no concession stands on the reservation; however, there are several restaurants and shops located where the Plum Island Turnpike ends just outside the reservation entrance. Facilities at Hellcat Swamp include restrooms, an information center, a public boat launch, and many wildlife observation areas.

Special comments: Although Plum Island’s 6.3-mile beach is closed from April 1 to August 31 to allow piping plovers to nest and rear their chicks, the Hellcat Trail remains open all year. Also, being an interpretive trail and entirely boardwalk, it is convenient for less able-bodied lovers of the outdoors and for families with small children. For those interested in increasing their hiking time, options include adding the Pine Wood Trail, located south of the Hellcat Trail and/or the Sandy Point Trail that loops around the southern end of the island opposite Ipswich Bay (see hike number 10).

NEARBY ATTRACTIONS

Newburyport boasts an assortment of attractions, including many historic homes listed on the National Register of Historic Places. An historic locale of unique appeal to boat lovers is Lowell’s Boat Shop, located in nearby Amesbury. The boat shop opened for business in 1793 and has been producing dories continuously ever since. For information about the boat shop, call (978) 388-0162. For information, schedules, and listings of special events, visit Historic New England’s Web site, www.historicnewengland.com. Though steeped in history, Newburyport is a vibrant commercial and cultural center with many excellent restaurants. The town’s independent cinema, The Screening Room, shows films frequently overlooked by mainstream megaplexes. To check show times, call (978) 462-3456 or consult the Web site: www.newburyportmovies.com.