PROLOGUE

Egypt 1915

a military, medical, and moral problem

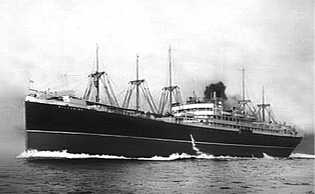

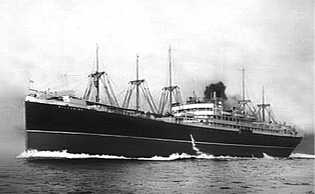

At sea near the southern entrance to the Suez Canal, one evening late in August 1915, hundreds of soldiers of the Australian Imperial Force stood in cooling breezes at the deck rails and portholes of a troopship, the A18 Wiltshire. Thick plumes of black coal-smoke whirled away from the vessel’s large funnel as she gathered way to the south, into the Gulf of Suez night, heading away from Egypt and towards Australia. As the sweltering heat of the day faded, the men on board watched the bright lights of Port Suez slowly disappear over the sea.

Until early that morning, all of them had been prisoners in a hot and crowded detention barracks at Abbassia in the city of Cairo. They had been moved from there that morning, under guard, to Suez and onto the Wiltshire, thence to be conveyed to another detention barracks far away at Langwarrin, near Melbourne. The 8,000-nautical-mile voyage on which they had embarked would take about a month, across the Indian Ocean via Aden and Colombo to Fremantle, then through the Great Australian Bight to Port Melbourne. When the Wiltshire departed from Egypt, it was late summer, but she would be greeted at her destination by a fine Melbourne spring.

The men on the Wiltshire had been banished from Egypt by the army. Very recently, in various AIF camps, each man had discovered he had a venereal disease. It was an offence in the army to conceal this, so each had revealed his condition to an army doctor, and had in turn been sent to the Abbassia barracks. It was crowded with hundreds of infected men being given painful VD treatments — repeatedly injecting and syringing them with toxic drugs. Every few weeks, when space was available on a troopship returning to Australia, a few hundred men were selected to be sent to Langwarrin.

The army had decided that each man in Abbassia was guilty of misconduct. Because of that, each had been abruptly removed from his battalion or regiment, and those who were non-commissioned officers were reduced to the ranks. As well, the army pay of each man was stopped for the duration of his VD cure, which could take months. The stoppage also meant that if a man had allotted part of his pay to a family member in Australia, that was also stopped — and without explanation. Before men were sent to Australia, they were told that, probably after their arrival in Melbourne, they would be discharged from the army for misconduct.

HMAT A18 Wiltshire, an Australian troopship from 1914 until 1919. (SLV)

This was what the 275 infected soldiers on the Wiltshire could look forward to: their pay had been stopped indefinitely, they were going to have daily injections and syringing all the way back to Australia, and then they might be discharged. What worried most of them, however, was the thought of having to explain all of this to those at home who cared about them. All privately knew that the journey they were taking might have to be kept secret forever.

The problems with the diseases they had acquired lay partly in the micro-organisms that caused them: in 1915, no reliable method had been developed to stop these troublesome bacteria from being transmitted during sexual intercourse; nor were there any guaranteed cures. But there was also a problem due to the victims’ perceived lack of morals, and that was perhaps worse. People with VD could have only been infected through pre-marital or extra-marital sex, and, in respectable Australian society, this was immoral. Even worse, the men in Egypt had become infected by having sex with prostitutes; this was doubly immoral and also foolish. Churches in Australia preached that venereal diseases were God’s punishment for sinners, and this certainly felt like the case to the infected men. Because of the heavy social stigma, those with VD tried to keep it a secret, and implored the doctors who attempted to cure them to keep the secret as well.

The men on the Wiltshire with VD were unusual: most AIF troops who passed through Egypt from the end of 1914 until mid-1916 did not become infected with venereal diseases. About 10,000 men, however, were treated at army hospitals for them during this period; and, because of unusual circumstances in 1915, 1,344 were sent to Langwarrin. Most had been infected in the brothels of Egypt, but some had been infected in Australia before they had left, and others at ports of call on the way.

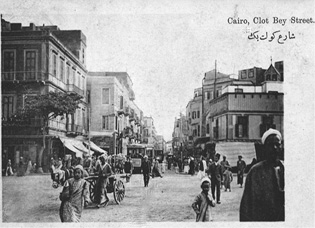

Egypt had been a world-famous centre for vice long before the Australians arrived, and things were made worse when 40,000 British soldiers had landed in Egypt in the 1880s and stayed permanently. They were an irresistible target for local sex-industry operators, and for traffickers of women and girls. To try to control the contagious VD that inevitably followed, the British made laws that had the effect of making prostitution tolerated. Districts in cities such as Cairo and Alexandria became fleshpots with bars, brothels, and sex shows for foreigners, and these even became tourist attractions.

How, then, was it possible for large numbers of young Australian soldiers to be sent to this infamous centre of vice and venereal disease?

Before the war began in August 1914, the Australian government offered to send 20,000 men to any destination desired by the British government, in anticipation of a possible conflict. The AIF was formed hastily, and troopships left Australia in October, heading for England via the Suez Canal in Egypt. A few days from Suez, however, the commander of the AIF, Major General William Bridges, received orders to disembark his force there and to continue the journey to England later. Accordingly, in December 1914, the Australians set up their camps close to Cairo — one just over the River Nile at Mena, and another at Maadi — and troopships from Australia continued arriving, bringing more men. For the next 18 months, thousands of well-paid Australian boys lived very close to the famous brothels of Cairo, and very far from their moral guardians at home.

Considered pornography in Australia, risqué postcards like this were freely available in Egypt for soldiers to buy. Pictures of semi-nude Moorish serving maids holding an amphora of wine were very popular.

The AIF’s troubles with venereal disease started just after the first contingent arrived from Australia before Christmas 1914. Plentiful leave was granted, and men made straight for the dance halls, brothels, sex shows, and bars in the Wasa’a — a cluster of crowded tenement buildings, shacks, and narrow alleys. These dizzy experiences were not available at home; and for the ‘Wozza’, the boys had money and freedom. There were brazen ‘tarts’ everywhere, and most were not wearing much clothing. The men barely noticed how shabby and filthy the place was, let alone its pervasive foul odours.

Australian troops lining the deck rails of the Wiltshire at Port Suez. On this occasion, it was December 1914, and the troopship was arriving in Egypt with the first AIF contingent from Australia. (AWM)

In this fabulous place, there was a very clear danger: the Wasa’a was well known for venereal diseases. The Australian soldiers who so eagerly queued in droves at the brothels were inevitably going to be infected with the common venereal diseases of the time: gonorrhoea (the clap), syphilis (the pox), and the genital sores of chancroid. In 1915, there was no reliable way for a soldier to protect himself against these, other than by abstaining from sex.

This innocent-looking postcard of Clot Bey Street in the centre of the Wasa’a district of Cairo was sent by many AIF soldiers to families at home. It was actually where prostitutes lived and worked, and at night was transformed into the world-famous brothel quarter.

If a man could not abstain, and bothered to be careful, he might use some prophylactic ointments that needed care to prepare, but were better than nothing. He could apply to his genitals a thick film of antiseptic ointments: Calomel, an anti-syphilitic that contained mercury; and Argyrol or Nargol, anti-gonorrhoeals that contained silver. If he followed exactly the elaborate instructions for using them, the bacteria might be killed. This was the method privately recommended by some Australian Army Medical Corps doctors to troops in their care, but was the subject of much disagreement. Vulcanised rubber condoms, called sheaths, were also available, but they were uncomfortable, easily damaged, and unreliable, and were not commonly used by sexually active soldiers in 1915. All of these prophylactics were morally controversial, and their use was disapproved of by the AIF commanders in 1915.

The worst part, however, was that, when obvious signs of infection appeared shortly after sex, there was no sure way of killing the bacteria that had entered the body. Gonorrhoea, syphilis, and chancroid were then known by doctors as diseases difficult to cure, either perfectly or quickly. The antibiotic penicillin, the first fast-acting and reliable anti-gonorrhoeal and anti-syphilitic drug, would not appear for another 27 years; and erythromycin, a fast antibiotic cure for chancroid, would be available in 37 years’ time. In 1915, the only medical treatments for the three diseases were lengthy, brutal, and uncertain.

Most venereal-disease drugs used at the time contained small amounts of the heavy metals mercury, arsenic, and silver, but other toxins as well. The usual cures for gonorrhoea involved introducing fluids to a patient’s body — containing silver in a drug called Protargol, or potassium permanganate, or sandalwood oil. These were repeatedly inserted into a male patient by syringing or douching through a nozzle placed in his urethra. The usual cures for syphilis were low doses of mercury in a drug called Hydrargyrum, or of arsenic in drugs with names like Salvarsan or Arsenobenzol, which were repeatedly injected into muscles and veins using hypodermic needles. The skin surface lesions and buboes of syphilis and chancroid were destroyed by repeatedly applying mercury in lotions and ointments. Mercury and sandalwood oil were also given orally, with patients consuming considerable quantities in a typical course. All of these toxic substances might kill the bacteria, but with many doses and over much time.

During the course of a cure, testing was done to gauge its effectiveness — especially after the visible symptoms disappeared. Simple testing to confirm if a man still had gonorrhoea was done by looking for pus threads in a sample of his urine. If laboratory facilities were available, testing for the presence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae was done using Pappenheim’s staining method, where a sample of pus in a microscope slide turned bright pink if gonorrhoea was still present. Another test was the Leszynsky method, which turned the Neisseria gonorrhoeae black. Testing for the presence of the syphilis bacteria Treponema pallidum pallidum was frequently done during a cure using the Wassermann antibody test on samples of blood.

The courses of treatment were not short — typically at least a month for gonorrhoea and a few weeks for syphilis and chancroid, but far longer if the infections had really taken hold or if multiple diseases were present, as was often the case. The toxicity of the drugs created unpleasant side effects in patients, so that the cures might feel worse than the diseases. There were also obstinate long-term venereal-disease complications for male patients, including gonococcal arthritis, gleet, urethritis, prostatitis, and orchitis. Men could still carry these side-afflictions long after the original disease had been apparently cured.

If treatment for gonorrhoea was not begun soon after infection, the unpleasant symptoms became worse, and the chances of obtaining a complete cure were reduced. Syphilis had to be treated in its very early stages, when symptoms were visible; after the signs of infection disappeared, syphilis could develop undetected to its dangerous latent stages. If a man with syphilis was not treated at all, or treated incorrectly, he could suffer serious long-term health consequences, including heart, organ, and brain diseases, and premature death. A man with venereal disease could easily infect others during sexual intercourse — perhaps his wife and, through her, his innocent children. In Australia, many children living in institutions for the blind, deaf, and disfigured had been infected before birth with the venereal disease of a parent.

By February 1915, the epidemic of venereal infections among Australian troops who had been in the Wasa’a was alarming their commanders. That month, a conference in Cairo of army doctors was told that about 1,000 men were in hospital with venereal disease every day. Despite the powerful stigma attached to the diseases, and general knowledge among soldiers in Egypt of the dangers, it was difficult to prevent many from becoming infected.

Soldiers who succumbed found themselves condemned by people of influence in Australia and Egypt who were united on military, medical, and moral grounds, and some of the infected men were sent back to Australia. Then, after the Gallipoli landing in April, and the very high number of casualties that had to be evacuated to Egypt, attitudes hardened towards men with VD. They were now unwanted occupants of AIF hospitals struggling to accommodate the Gallipoli wounded. An order was given that all venereal cases were to be banished from Egypt and sent to Australia. Thus began, in May 1915, a procession of shiploads of infected men from Suez Canal ports to Port Melbourne, from where the men were taken to Langwarrin.

This was to be the destination of our poor wretches on the A18 Wiltshire, now far out in the Red Sea night as the ship rolled and pitched in the long ocean swells. Would they be discharged from the army at Langwarrin? What would they have to do to get back to the war, if indeed they wanted to do that at all? How could they keep their secret from those at home, and conceal what had happened to bring such shame?

But, before answering those questions, we first need to understand the opinions held by senior officers and army doctors in Egypt about soldiers who caught venereal disease. We also need to know about the decisions they made in 1915 that led to the making of the Wiltshire’s voyage.