CHAPTER ONE

William Birdwood, William Bridges, and Charles Bean

sodden with drink or rotten from women

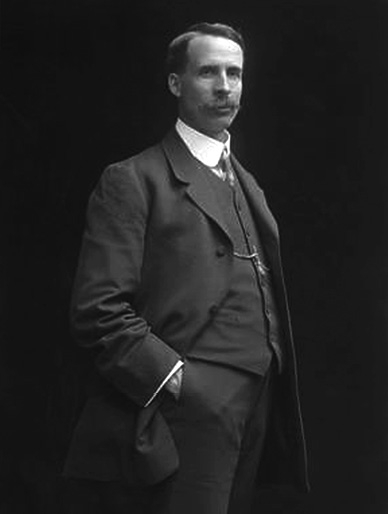

The Australian soldiers becoming infected with VD in Cairo were clearly unaware that the British generals who commanded them did not tolerate sexual misconduct at all. Their supreme commander was General Herbert Kitchener: Lord Kitchener of Khartoum, the secretary of state for war in London. He was a puritan, and his acerbic opinions about soldiers who caught venereal disease were very well known in the British army, but not yet to the AIF troops. Kitchener’s views were fully understood by Lieutenant General Sir William Birdwood, who had been handpicked by him to command the Australians, and who had been close to Kitchener for years. When the VD problem started in Cairo, Birdwood ordered Major General Bridges to stop it by taking on methods used by Kitchener for the British army. To do parts of this work, Bridges sought the assistance of Captain Charles Bean, the newspaper correspondent accompanying the AIF.

Lord Kitchener in 1915. (Bain News Service; Library of Congress)

Before the First World War, at the height of the British Empire, Lord Kitchener had been one of the standard-bearers of a movement to affirm the virtues of British masculinity — believing that imperial success was assured only if Englishmen were morally of good character, and physically pure and strong. Kitchener set the example in his personal life by living austerely, following a daily routine of Spartan rigour, and controlling sexual urges.

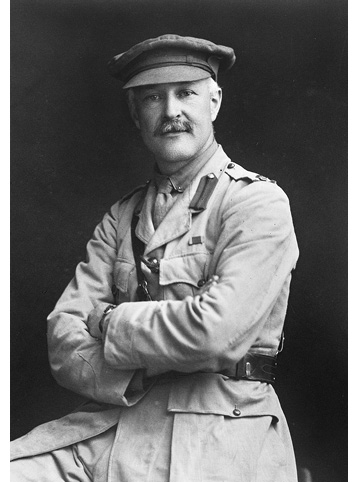

Lieutenant General Sir William Birdwood. (SLV)

General Birdwood was an authentic puk’ka sa’hib officer of the Indian army: genteel, decent, charmingly correct, and definitely superior. He served the empire in India for 15 years until 1899, when, at the outbreak of the Boer War, he was sent to South Africa and became General Kitchener’s military secretary. Kitchener was also an Indian-army man, and, after the Boer War, he and Birdwood returned to India, and their close association continued. After Kitchener became commander-in-chief of the Indian army in 1902, Birdwood enjoyed a rapid rise to the rank of major general.

In the Indian army, Kitchener’s puritanism had put him at odds with other generals, who could be more forgiving if officers and men became profligates during their postings. Many men became unfit for military duty because of drunkenness and venereal disease, and VD outbreaks in the Indian army had, on occasions, seriously depleted its fighting fitness. During the 1890s, the percentage of men admitted to hospitals in India with gonorrhoea and syphilis had reached the staggering proportion of over 50 per cent of all troops. There was a parliamentary inquiry in London, and methods were devised to deal with the problem, including tolerating the use of regulated brothels. But when Lord Kitchener became commander-in-chief, he could not approve of such tolerance. He exhorted his troops to be abstinent and to live healthily like him; men who could not might be punished, and would certainly be denounced. After the outbreak of the First World War, the British army published a pamphlet about avoidance of VD that was based on Kitchener’s ascetic views, and contained a message from him:

It is discreditable and even dishonest, that by contracting through self-indulgence a disease which he can avoid, a man should render himself incapable of doing that work for his Country which he enlisted to do.

So when, in November 1914, Kitchener gave command to Birdwood of the military forces of Australia and New Zealand, it was going to be impossible for sexual misconduct to proceed unnoticed and unpunished. In early December 1914, Birdwood left India with the temporary rank of lieutenant general; he arrived in Cairo a few days before Christmas, shortly after General Bridges and the Australians had arrived.

Captain Charles Bean in France in 1919. (NLA)

Charles Bean had also recently arrived with the AIF’s first contingent. He had been a journalist on the Sydney Morning Herald until September 1914, when he was chosen to be Australia’s sole official war correspondent. For this new job, he was given the honorary rank of captain and was attached to the headquarters of the 1st AIF Division. Although Bean had been born in Australia, he had for 15 of his formative years lived and been educated in England, where he had become very respectful of British traditions, and impressed by the ideals of the imperial way.

Major General William Bridges. (Falk Studios; SLNSW)

In Cairo with the AIF in December 1914, and although young and a mere captain, Bean discovered he had unrivalled access to the senior British and Australian officers of the imperial force. He got to know General Birdwood, General Bridges, General Sir John Maxwell, who commanded all British forces in Egypt, and especially Colonel Cyril Brudenell White, who was chief of staff of the AIF division. From his written descriptions of them, it is apparent Bean was in awe of these very senior men. He began regularly dining with some, travelling with others to inspect military activities outside Cairo, and frequently consulting them about the kinds of stories they might approve of his sending away. With their blessing, he cabled innocuous, informative news stories to Australia, which were published in many newspapers. On Christmas Day 1914, he cabled a story about dinners given for the men, how mail from home had arrived, and how soldiers had climbed the pyramids and engaged in sports. Bean also reported that ‘many of them spent the afternoon and evening in Cairo’.

On New Year’s Eve, Bean cabled a story about a march that day of Australian troops at the Mena camp, and quoted General Maxwell describing this ‘splendid sight’, and Birdwood saying that it was ‘quite first class’. But, in truth, what had really happened during this period, and could not be reported by Bean for Australian newspapers, was that, before Christmas, some of the Australian and New Zealand troops had discovered the Wasa’a district in Cairo. On Christmas Day, when all of them had been given a holiday, swarms had descended upon the area. So began night after night of absences without leave, riotous binge-drinking sessions, and visits to brothels — and the first symptoms of gonorrhoea, syphilis, and chancroid infections that appeared on hundreds of soldiers after they eventually drifted back to the AIF camps.

As this outbreak of mass misconduct unfolded, Bean began recording in his diary his aghast observations of what was occurring, each day filling page after page:

There was a time about Christmas when the sights in the streets of Cairo were anything but pleasant for an Australian who had any regard to the good name of Australia. There was a great deal of drunkenness & I can’t not help noticing that what people in Cairo said was true — the Australians were responsible for most of it.

For Bean, and evidently for Birdwood and Bridges as well, outrageous behaviour like this should not have been happening at all. Men sent to the war by Australia were meant to be her best — a demonstration to the world that the new nation should be admired. Recruitment standards were supposed to have been deliberately high, and recruiters were expected to select men of good character. Soon, when describing to the Australians in Egypt what they were meant to be upholding, Bean wrote:

Amongst [the Egyptians] we have a great reputation for high principles and manliness, and even the humblest Britisher here in the East carries that reputation in his keeping … The one thing the natives have come to know about British troops … was that the British soldier never interfered with their women and never interfered with their religion. There is a third point in our reputation. Throughout this country the phrase for ‘truth’ or ‘good faith’ is ‘word of an Englishman’. Is not that something for our whole race to be proud of?1

General Birdwood decided the misconduct was a result of the rush to form the AIF from scratch a few months earlier. There had been few opportunities since then to instil the standard of discipline needed to make good soldiers. Until that could be done, he decided to make the entire city of Cairo out of bounds for Australian and New Zealand troops, and issued the necessary orders. As it happened, the bounds were repeatedly broken, and the rampage went on. Bean then noted in his diary a dramatic action taken by Birdwood to stop it:

When I got back from Cairo the other night General Bridges had a letter from General Birdwood and he would show it to me. From what he said I take it that he would not take it amiss if I sent a letter & a wire to give people in Australia some idea of how things are; we shall probably be getting rid of a few of these old hard heads — sending them back to Australia.

The agitation of General Bridges, and his discussion with Bean about getting rid of troublemakers, was caused by the alarming contents of Birdwood’s lengthy letter, which, in a most courteous way, ordered Bridges to stop the misconduct. Written in late December 1914, when Birdwood had clearly lost patience, his letter said that Sir John Maxwell had complained about the Australians, and it contained a number of criticisms of them, including that ‘men seemed to think they have come here for a huge picnic’. It also said, in words reminiscent of Lord Kitchener’s, that the Australian government was relying on the AIF to uphold Australia’s good name:

But there is no possibility whatever of our doing ourselves full justice unless we are every one of us absolutely physically fit, and this no man can possibly be if he allows his body to become sodden with drink or rotten from women, and unless he is doing his best to keep himself efficient he is swindling the Government which has sent him to represent it and fight for it.2

The letter ended by informing Bridges how Lord Kitchener was ‘following every movement of ours with unfailing interest, and surely we will never risk disappointing him by allowing a few of our men to give us a bad name’.

Birdwood seemed to think that only a hard core of the men was involved; his letter referred only to a ‘very small proportion of our contingents in Cairo’. Within weeks of him writing to Bridges, however, there would be about 1,000 venereally infected men in hospital every day. Bean began making diary notes about the extraordinary numbers:

There was a great deal of disease amongst our men, which they brought on themselves by their indulgences in Cairo. The disease is simply deplorable, but apparently quite unpreventable. Cairo is a hotbed of it — in particularly serious forms & some of the cases are simply tragic; young soldiers, really fine clean simple boys who have been drinking & have found themselves with a disease which may ruin them for life. In one case which I heard of, the youngster was said to have been made drunk by two older soldiers.

Some of our commanding officers have had boys come to them — bright decent youngsters who in Australia would have been ashamed to do or think of the things, or go near the places into which they have been led here — the youngsters have come to them almost in tears bitterly ashamed & half horrified with themselves.

Birdwood knew exactly what Kitchener would want him to do. AIF men should be diverted from vice, and those who continued to catch VD should be dealt with severely. He proposed to Bridges that far more attention should be given to improving the physical fitness and self-pride of the troops, and to developing healthy recreational diversions for them. General Bridges then arranged to intensify physical training — including long route marches in the desert, competitive sports and athletics carnivals, and especially wrestling and boxing tournaments. The Red Cross and the YMCA were invited to open attractive recreation halls in the AIF camps, and dry canteens in Cairo, to lure men from the Wasa’a. As well, battalion and medical officers, and especially army chaplains, were directed to give regular talks to their troops about the perils of strong drink and promiscuity. This included straight talk for newly arrived troops even before they had disembarked from the troopships. A medical officer addressed troopers of a Light Horse regiment, and told them about the diseases in a straightforward way:

When men who were badly affected in this way married, their children were a terrible disgrace to them. He [told] the Light Horsemen of the appalling mortality rate amongst those venereally affected. Barring Port Said, Cairo was about the worst city in the world, and full of women of bad reputation, with whom he advised and urged the men to have nothing whatever to do; it would be highly dangerous.3

The physical training, healthy recreations, and practical talks by medical officers probably did reduce the appeal of the Wasa’a for some, but the use in Egypt of army chaplains to give church-parade sermons about the diseases was not so successful. During parades, men might be invited to make pledges of sobriety and Christian chastity, and join rousing prayers for protection from the ‘God of Battles’; they were encouraged to sing popular hymns for soldiers like ‘Where Is My Wandering Boy, To-night?’ AIF chaplains preached that venereal disease was a moral problem, and that only men of virtue could be protected from it by God. The chaplaincy service would persist through the war with a morals campaign that the official medical historian would later describe as ‘worse than useless’ for stopping VD.

Notwithstanding the medical lectures, and in spite of the sermons, the misconduct and infecting of soldiers continued. So, in accordance with Lord Kitchener’s known views, Birdwood and Bridges began invoking sections of the army regulations that provided punishments for men who caught VD. At the time, most regulations for the Australian army were copied from the King’s regulations for the British army. Under these, catching VD was not a crime in itself; but because the usual instinct of an infected soldier was to keep it a secret, there was a regulation that forced him to reveal it, under threat of punishment if he did not. Since a soldier might be reluctant to co-operate for VD treatment, he could be ordered to submit, and the regulations provided punishments if orders were disobeyed.

Another method provided in the regulations was a rule enabling a soldier to be discharged from the army because of medical unfitness caused by misconduct. That possibility was contained in an AIF circular signed by General Birdwood in February 1915, part of which read:

Warning to Soldiers respecting Venereal Disease

Venereal diseases are very prevalent in Egypt. They are already responsible for a material lessening of the efficiency of the Australian Imperial Forces, since those who are severely infected are no longer fit to serve. A considerable number of soldiers so infected are now being returned to Australia invalided, and in disgrace. One death from syphilis has already occurred.

Intercourse with public women is almost certain to be followed by disaster. The soldier is therefore asked to consider the matter from several points of view. In the first place if he is infected he will not be efficient and he may be discharged. But the evil does not cease with the termination of his military career, for he is liable to infect his future wife and children.4

Another regulation allowed the stopping of a soldier’s pay while he was in hospital with a disease not incurred as a result of military duty. This was, originally, not intended to be a punishment, but, in practice, became one for men with VD. In January 1915, General Bridges cabled the minister for defence, Senator George Pearce, with a request for him to approve stopping the pay of AIF soldiers catching VD. Pearce quickly obliged, and the approval he gave was backdated to December 1914 to include soldiers already infected. Within days, Bridges issued Divisional Order 398, which stated: ‘No pay will be issued while abroad for any period of absence from duty on account of venereal disease.’ The order exempted officers, warrant officers, and non-commissioned officers, but it also stipulated that wages allotted by a soldier to his family were also forfeited, and would have to be made up after he was cured before he could again receive pay.

Senator George Pearce. (NLA)

Australian soldiers in Egypt were paid generous wages compared with those of other imperial troops. They were each on a daily rate of at least six shillings — more than three times the pay of a British soldier — and this was a reason that Australians had so much money for indulgences in Cairo. The high AIF pay had attracted recruits: there was unemployment in Australia, soldiering seemed like a lucrative job, and some were financially supporting wives and parents at home by having allotted pay for them. The stopping of allotments by the army was deliberately intended to expose an infected soldier’s moral sin to those close to him — ‘a kind of prophylactic blackmail’, as it was later described.

Presumably, the drastic order to withhold pay and allotments must have stopped men from visiting brothels, and must have reduced infection rates. What is known is that, when army paymasters began doing this, soldiers who lost their pay were very upset. They had not expected it, and felt it was unfair, because the duration of a VD treatment was something over which they had little control, and could go on for months.

To further intensify the punitive campaign against men who became infected, it was initially arranged for them to be isolated at a camp near the aerodrome at Mena. The barbed-wire enclosure for men with VD was arranged with particular rigour: they were closely supervised by sentries who were instructed to be unfriendly, they were made to wear a white armband, they could not receive food or articles from outside, and, if mates came to visit them, these visitors could be arrested. Soon after the camp was opened, a medical officer who was sent to inspect it reported that

The men in the camp suffering from venereal disease are deprived of pay, they know they are in disgrace, and many of them are sullen and in an attitude of almost aggressive insurgence. Some of them would I believe respond to sympathetic treatment, and efforts could be made to arouse in them some human interest. Those who are positively objectionable should in my judgment be punished with severity. I do not think many punishments would be necessary.5

From December 1914, there were also discussions among senior AIF officers about the possibility of sending the worst of the misbehavers, drunks, and ‘venereals’ back to Australia. They realised that the Australian public might be surprised if this were to happen, and might need forewarning. To do this, General Bridges enlisted the help of Charles Bean to cable an explanatory story to newspaper readers at home. At the same time, Bean obtained the general’s approval to write a guidebook to Egypt for Australian soldiers, which was to include warnings about alcohol and venereal diseases. Both of these writing projects were well meaning in intent and thoroughly prepared, but the first was to backfire spectacularly for Bean.

His long and quite cautious article began appearing in Australian newspapers in late-January 1915. It mostly comprised praise for the troops of the AIF, and spoke admiringly of them. But it included criticism of ‘only a small percentage — possibly 1 or 2 per cent … a certain number of men who are not fit to be sent abroad to represent Australia’. To Bean’s later regret, editors all over Australia reworked the story and published it under sensational headlines, such as ‘WASTERS IN THE FORCE — SOME NOT FIT TO BE SOLDIERS’ and ‘TOO MUCH LIQUOR’. The treatment was in response to Bean having not just described misconduct and drinking, but also men who had ‘contracted certain diseases by which, after all the trouble and months of training and of the sea voyage, they have unfitted themselves to do the work for which they enlisted’.

There was a horrified reaction by readers, many of whom had husbands and sons in Egypt. Anxious to play down the hitherto-hidden problem now revealed by Captain Bean, Australia’s wartime leaders had to step in. The prime minister, William Morris Hughes, issued a statement saying, ‘It is no doubt a very serious matter, but I should be more concerned if I believed such conduct fairly reflected the code of the Expeditionary Force generally. I don’t believe it does for a moment.’ Senator Pearce had this to say in response to the Bean story:

It is to be remembered that these forces were very hurriedly got together, that men were unknown to the officers in a great number of cases, and that it takes some trouble and time to try out any body of men and discover the ‘wasters’. The officers have any amount of power to punish offenders, but the best means of dealing with them — and what will be the greatest punishment and disgrace — will be to send them home again.6

Within days of the senator’s comment, the sending home of men was ordered by General Bridges. On 3 February 1915, the A55 Kyarra, then an Australian hospital ship, departed from Suez carrying 341 men to Australia, including ‘invalids and [those] unfit for service’ and 132 VD patients. The army had declared that each of these was ‘Unlikely to become an Efficient Soldier’ and that they were to be ‘Discharged–Services No Longer Required’ on arrival in Australia. Their publicised removal from Egypt was meant to send a strong warning to others. The Kyarra thus became the first of a series of homeward-bound ships that left Egypt during 1915 carrying the rejects of the AIF.

Publication of Charles Bean’s article began the first controversy of the war for Australia, and it spawned much discussion. Letters were sent to Egypt seeking re-assurance from soldiers there; back came replies angrily denying that such things were occurring. Anger was also directed at Bean for making his allegations: he was threatened with tarring and feathering, was told he would ‘stop a bullet’ sooner or later, and became the target of a witty mock-doggerel poem of ten verses that was published in a Cairo newspaper. This asked him to

Cease your wowseristic whining,

Tell the truth and play the game,

And we only ask fair dinkum

How we keep Australia’s name.

Bean’s discovery that other Australians so strongly objected to what he thought was a morally principled story shook his self-confidence. In a conversation with himself in his diary, he said he could not understand the reaction, and referred to how General Bridges had asked him to write the article, and saw nothing objectionable in it. There was one AIF officer, however, who thought the article was very offensive. Colonel John Monash was commander of the 4th Infantry Brigade, and had also led the convoy carrying the second AIF contingent to Egypt. He mistakenly took Bean’s article to be criticism of himself and his men. In March 1915, he wrote to Senator Pearce to complain about the ‘lurid stories’ of ‘drunken and immoral orgies’, and appealed to the senator ‘that for the sake of our parents, our wives and our children, you will not allow our good name to be tarnished in Australia’.7

Bean made amends for starting the furore by publishing the booklet What To Know in Egypt: a guide for Australasian soldiers. This contained a short history of Egypt and the Nile River delta, and descriptions of the people, religions, and antiquities of Cairo. There was practical advice about diet, distances, and currency, and useful phrases in Arabic and French. In ‘A Few Short Rules — Women’, he wrote that ‘Men must be careful to avoid any attempts at familiarity with native women; because if they are respectable they will get into trouble; and if they are not, venereal disease will probably be contracted.’ In a long section about ‘Health in Egypt (what is unsafe — and the reasons why)’, Bean covered sanitation, typhoid, and dysentery. Under the heading ‘A hot bed of disease’, he elaborated on the subject of VD:

Modern Cairo with its mixture of women from all nations, East and West has long been noted for particularly virulent forms of disease. Almost every village contains syphilis. And if a man will not steer altogether clear of the risk by exercising a little restraint, his only sane course is to provide himself with certain prophylactics beforehand to lessen the chances of a disastrous result.

By mentioning prophylactics, Bean was touching on an acutely sensitive subject. Even though educating soldiers about prophylactics, let alone providing them, were obvious measures for reducing VD, no senior officer wished to be associated with such activities at this early stage of the war. Some believed it would be condoning immorality; others, who felt that prophylaxis was unreliable, feared it might result in more infections. In early 1915, General Birdwood was asked by an Australian medical officer, Major James Barrett, to seriously consider issuing prophylactics to men going to brothel areas, but Birdwood refused.

Following the reaction to his newspaper article, Charles Bean never again wrote stories that could be construed as criticism of Australian soldiers. Even though the drunkenness in Cairo continued until early April 1915, when most ANZAC troops left for the Dardanelles, and the daily rate of men being treated for VD barely declined, there was not another article from him about it. As an example, just before departing from Cairo, the soldiers were granted short pre-embarkation leave. That evening, many went to the Wasa’a district and ransacked the brothels and drinking halls, setting some on fire. A number of reasons were given then, and have been since, for this famous act of vandalism, but it seems the main cause was a desire to wreak vengeance on a place that so many had previously been eager to visit. That night, Charles Bean inspected the wreckage, and wrote a diary account of what had happened. A few months before, he might have condemned the Australians, but this time he wrote, ‘I have known rows of exactly the same sort at Oxford & Cambridge, carried through in precisely the same spirit, & people only called it light-heartedness there.’

Bean accompanied the AIF to Gallipoli; during his absence from Egypt, and after his return, the misconduct and venereal infections continued, well into 1916, until the AIF moved from Egypt to France. There and in England, drunkenness, crime, frequent absences without leave, and a high rate of VD became a permanent part of AIF life, but there would be hardly a word about it reported by Bean.

Throughout the Dardanelles campaign, General Birdwood continued to command the ANZAC forces, and also became the AIF commander after General Bridges was mortally wounded at Gallipoli. Following the end of that campaign, Birdwood oversaw a doubling in size of the AIF in Egypt during 1916. It was here that, in March, VD infection rates reached record levels. The Australian surgeon-general, Colonel R. H. J. Fetherston, wrote to Birdwood, imploring him to bring an end to it:

I now have over two thousand of your troops under treatment for venereal disease. It is with diffidence that I again call your attention to mitigate this growing evil. Would it be possible to place the streets [in Cairo] where the principal brothels are located out of bounds?8

Birdwood then led the AIF from Egypt to Europe, and through all the campaigns in France and Belgium, until May 1918, when he handed command of the Australian Corps to John Monash, now a lieutenant general. During his long period with the AIF, Birdwood saw the dismantling of almost every measure introduced in Egypt to stop venereal disease. The first to go was the mandatory return of infected men to Australia, when, in October 1915, a decision was made in Melbourne to keep troops who became infected well away from home.

Then, beginning in mid-1916, it was realised by AIF medical officers that wartime conditions in Europe had produced moral standards quite different from those the pre-war world had regarded as civilised. There was also a loss of the ability, or even the willingness, of civil, religious, and military leaders to prevent wartime promiscuity. These conditions were perfect for the spread of venereal infections, which became far worse than anything experienced by the AIF in Egypt. During the war in Europe, millions of men and women became infected with VD — mostly during the last two years of hostilities, when the war entered a most intense and destructive phase. In the British and dominion armies alone, there were over 400,000 admissions for venereal diseases to military hospitals.

The mass slaughter of Australian soldiers started in Europe in mid-1916 during the long campaign at Pozieres and at Fromelles. Very high casualties caused a constant need for more manpower, and the AIF could not exacerbate this problem by leaving large numbers of troops out of action due to VD. Because of this, the policy for handling it underwent a series of pragmatic changes, and the use of punishments as the only form of cure began to be supplemented before being mainly replaced by medical methods. The reason was explained by Lieutenant Colonel Graham Butler, an AIF medical officer, at a conference in Paris arranged by the Allied Powers to discuss VD. He said that

The Australian at home is not a loose-living man; but it was obvious that very systematic and definite measures would be required to avert a serious interference, by venereal disease, with military efficiency and also a danger to the future of the race.

Lieutenant Colonel Graham Butler in 1916. (AWM)

An event that might have helped General Birdwood accept this reality was the removal in June 1916 of the powerful influence of Lord Kitchener, who was drowned after the British armoured cruiser HMS Hampshire, on which he was travelling to Russia, struck a German mine and sank in the North Sea.

In the scheme of preventive and curative medicine for VD that was introduced by the AIF in 1916 and perfected on a large scale by 1917, the only retained part of the old methods was to continue the health-education campaign devised in early 1915 in Egypt. Apart from describing to the troops the nature of the diseases and the contributory effect of drinking alcohol in spreading them, the essence of the new education campaign was, in Colonel Butler’s words, ‘denunciation of the idea that continence is ever harmful, and that incontinence is an essential attribute of manliness’.

In Egypt in early 1915, any proposal for the AIF to issue prophylactic kits had been rejected by General Birdwood on moral grounds. In Europe, that position was completely abandoned: prophylaxis was deliberately adopted as AIF policy. Huge quantities of Calomel and Nargol were procured and packed into what were variously called Blue Light, Blue Label, or ‘dreadnought’ kits, and these were freely available for men going on leave to use immediately before and after sexual intercourse. Hundreds of thousands of the kits were issued free of charge at AIF depots in Europe and England, and condoms were made available for sale. As well, there was free provision of ‘preventive early treatment’ at medical-corps preventive-medicine sections in every army unit, called Blue Light depots. Early treatment involved a medical examination immediately after a soldier might have been exposed to VD, and precautionary use of Calomel and Nargol. Hundreds of thousands of inspections were made.

This Blue Light prophylactic kit is similar to those issued in the AIF from 1916. One of the tubes contains Calomel ointment; the other contains Nargol jelly. (Museums Victoria)

To deal with cases when early-treatment inspections showed definite signs of disease, there was free provision of what was called ‘abortive treatment’. This was an attempt to kill VD bacteria at the very early stages of infection, in the hope of avoiding having to send men to a hospital for much longer treatment. About 20,000 infected men received abortive treatment, and about 15,000 were cured.

If the use of prophylactics, early preventive treatment, or abortive treatment failed, and an infection developed beyond the stage where it was quickly treatable, men were admitted to hospital. This was usually to the AIF venereal-disease hospital at Bulford in England, but some were also treated at hospitals in France. Bulford operated from 1916 until 1919, and had about 30,000 admissions — many for soldiers with multiple infections, and many being repeat visits.

Since early 1915, the main measure used by the AIF as a deterrent and as a punishment had been full stoppage of pay. In Europe, the regulation had been re-affirmed in December 1916, with officers, warrant officers, and non-commissioned officers now included. This was the last of the measures introduced in Egypt to be discarded in Europe, and the change was approved by General Birdwood himself. In January 1918, his AIF Order 1282 relaxed the regulation, and, from that time, men in hospital with VD would only forfeit one-third of their pay.

In Cairo in early 1915, long before all the VD rules were relaxed, General Birdwood, General Bridges, and Captain Bean had the confidence, which came from knowing they were right, to take principled positions about the venereal diseases incurred by Australian soldiers. They had no way of forseeing that what went on in the Wasa’a district would increase dramatically in Europe. In 1915, they were unable to know that much of what they stood against would soon become normal.

Nobody knows how many Australian soldiers caught VD during the First World War, partly because not all treatments were recorded or reported, and partly because not all those who were infected revealed themselves. However, as will be seen later, between 1914 and 1919, at least 60,000 infected soldiers were recorded to have been treated by AAMC doctors in army depots and hospitals — many more than once.