CHAPTER TWO

James Barrett and John Brady Nash

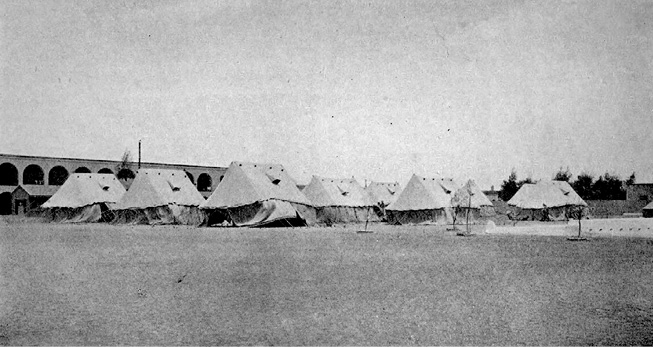

the isolation-detention barracks at Abbassia

In early 1915, the doctors of the Australian Army Medical Corps in Cairo knew their main duty was to prepare for the casualties of battles the AIF might soon be engaged in. Most arrived en masse in mid-January on the Kyarra, the first hospital ship to arrive from Australia. This was the same vessel that would shortly carry back to Australia the first group of men with venereal infections. The Kyarra brought a number of complete hospitals, and each was dispatched by rail to its assigned camp at Cairo. Some were established in tents and marquees; others, in permanent buildings in the city.

Another duty of the AAMC doctors was trying to protect the troops from infectious diseases. In the dusty and fly-ridden Cairo camps, close attention was given to hygiene and sanitation to prevent infections from local bacteria and viruses. With so many men crowded together, the doctors were especially alert for predictable contagious diseases spread by personal contact — such as chickenpox, influenza, measles, mumps, and meningitis — and isolation wards were prepared in case of outbreaks.

Within weeks of their arrival, however, the surprised doctors found themselves confronted with thousands of soldiers suffering from contagious diseases that had not been predicted on such a large scale, and for which they were not equipped to prevent or cure. Although some cases of venereal disease had been expected, as in any army, what the doctors faced was an epidemic. For instance, soon after the 520-bed 1st Australian General Hospital was established at the Heliopolis Palace Hotel in Cairo, the number of venereal patients became so great that another 500 beds were added. The 300-bed 2nd Australian Stationary Hospital at the Mena camp was, by the end of January, completely filled with venereal patients, with 150 more waiting to be admitted. To the AAMC doctors this was astonishing, because these were contagious diseases that were entirely avoidable. Catching gonorrhoea, syphilis, and chancroid involved a deliberate exposure to infection from a sexual partner, but here were thousands of men becoming diseased entirely through their own actions.

On 17 February 1915, a conference of senior AAMC officers was arranged at the 1st Australian General Hospital at the Heliopolis Palace Hotel.9 The meeting was asked to ‘devise an efficient means of combating venereal disease in the Australian Imperial Force’. All the men who attended had until recently been prominent doctors, surgeons, or medical specialists in Australia, with the exception of Colonel William Williams, the surgeon-general and director-general of medical services for the AIF, who had been the army’s only full-time doctor when the war started. As respected senior members of Australia’s medical profession, all enjoyed great social status and substantial incomes. Some had already been rewarded with high royal honours, and others would be knighted as the war progressed.

A number had offered their services on a pro bono basis as a patriotic duty. Some had taught in medical faculties at the universities, where they were esteemed, and all were active in Australian branches of the British Medical Association and other bodies for the advancement of medical science. Most had experience with military medicine in the militia, and a few had been medical officers in past wars. Some had also been professional rivals in Australia, and had brought their rivalries, and substantial egos, to Egypt, where they would engage in behind-the-scenes struggles and power plays.

The spectacular Heliopolis Palace Hotel in Cairo, which was occupied by the 1st Australian General Hospital from January 1915. (Barrett and Deane (1918))

The gathering in February 1915 at the Heliopolis Palace Hotel could be portrayed as a mighty medical brains trust, brought together to solve a major medical problem for the AIF. The records give the impression, however, that not all the doctors in attendance wanted to become overly involved. Such esteemed medicos might have felt reluctant to develop a too-close association with these medically difficult and morally controversial diseases. Their disdain for the venereal diseases, and the infected men, too, reflected attitudes held within the medical profession more generally; venereology was considered to be particularly unglamorous.

But there were two prominent doctors at the conference who would become deeply involved with resolving the AIF’s VD problem in Egypt — one in a most committed way, the other reluctantly — and they would become remembered for this. We shall return to these two in due course.

Those at the conference included the three most senior Australian medical officers in Egypt: Colonel William Williams, Colonel Charles Ryan, and Colonel Neville Howse. Colonel Williams had served as a medical officer in Sudan and South Africa, and in 1902 had been appointed surgeon-general of the army. In August 1914, he had been chosen by General Bridges to prepare the medical corps for its role with the expeditionary force. He had only recently arrived in Egypt when the VD problem was suddenly thrust upon him. In early 1915, Williams was perceived to be at the end of his career; he was 58, had advanced cardiac disease, and was becoming medically unfit.

He opened the conference proceedings by noting that

It was estimated that about 1,000 men of the 1st and 2nd Australian Divisions are suffering from Venereal Disease at any one day, and of these a large number are incapacitated from working. The proportions seemed to be much greater than those of other forces, such as the Territorials in Egypt. The displacement of so large a proportion of men, and the ultimate consequences of numerous infections, rendered it necessary to take a comprehensive view of the position, and to endeavour to take some action to minimise the damage done.

The conference launched into discussing the problem under five subjects: ‘Military assistance’, which was stricter control over men in brothel areas, and punishments for those who became infected; ‘Use of prophylaxis’, the possible provision by the army of prophylactics for soldiers; ‘Treatment — general and special’, the medical methods to be used to cure the diseases; ‘Establishment of convalescent depots’, the removal of VD cases from general hospitals to isolation facilities; and ‘Ultimate destination of affected men’, which considered the advantages and disadvantages of treating patients in Egypt or sending them to Australia.

The agenda was arranged to facilitate open discussion about the clear military and medical aspects of the disease outbreak. There was also an important item not on the published agenda — one more difficult to deal with, and which could not be openly spoken of. This concerned the immorality of soldiers engaging in sexual activities and deliberately exposing themselves to contagious disease. Some doctors at the conference had strong, privately held opinions about this that could not be easily separated from purely military or medical aspects.

At this point, it is important to know there was an influential guiding mind behind the Heliopolis conference, a person who was its secretary and was recording the proceedings. This was Major James Barrett, the registrar of the 1st Australian General Hospital, where the conference was being held. In Melbourne, he was an eminent ophthalmologist, surgeon, medical researcher, and lecturer; well-known, well-connected, and wealthy, with a magnificent home in Toorak, and the recipient of an appointment by King George V as a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George.

Sir James Barrett in Melbourne in 1919. He is wearing a KBE, CB, CMG, Order of the Nile, and war decorations and medals. (UMA Lafayette)

Barrett had joined the AIF without military experience, and offered his considerable talents to the army pro bono. Upon arriving in Egypt, he had acquired a number of roles, each of which was a challenging job in itself: consulting oculist to the AIF, registrar of the hospital, and executive officer of the regional Australian Red Cross. Because of this last job, he spent much time in Cairo cultivating relationships with senior AIF leaders, diplomats, and influential members of the local British ruling class. To his AAMC colleagues, Barrett seemed to have an opinion about everything and a finger in every pie, and soon — and almost certainly unwittingly — he made himself the subject of unkind jokes. He also promoted an unpopular opinion that venereal diseases were, first and foremost, medical problems, to be controlled using all the tools of preventive medicine, including prophylaxis.

Colonel Charles Ryan had been, until the war, a surgeon at Melbourne Hospital and at the Children’s Hospital in Carlton. In August 1914, he had become assistant director of medical services for the AIF, and, after he arrived in Egypt, he had been assigned to ANZAC headquarters. At the Heliopolis in 1915, Colonel Ryan made only a modest contribution to the discussion. He suggested it would be difficult to place the brothels out of bounds because they would move to other areas, and instead thought that venereal cases should be isolated, and that men with syphilis should be sent home.

Colonel Neville Howse, VC, in Cairo. (NLA)

Colonel Neville Howse was a well-known military hero who had been awarded a Victoria Cross in the Boer War. He was now the assistant director of medical services for the AIF, and during the Heliopolis conference had plenty to say. He said military police could not control brothel areas in Cairo, since they had no power under the law. He noted that some officers had tried to get soldiers to take VD precautions, and none had been taken. He thought that issuing circulars about VD to arriving troops was ‘a waste of time’, pointedly noting that those given circulars by Major Barrett ended up having a greater chance of being infected than those who received none. Howse played down the VD problem, and also suggested it was partly the fault of medical officers in Australia sending to Egypt men who were already diseased. He agreed with Colonel Ryan that syphilis cases should be sent home.

Apart from Williams, Barrett, Ryan, and Howse, there were seven other doctors at the Heliopolis conference, but only a few made contributions of note. There was general agreement that syphilis cases should go to Australia, and that hospitals should not be filled with gonorrhoea patients who ‘required little more than rest’. One doctor raised the problem of choosing which venereal cases should be returned to Australia, observing that ‘officers had also to recollect that the future of these soldiers was to be considered and the part they would play in civil life’. Others noted that an ‘outstanding feature’ of the venereal-case statistics was the comparative absence of syphilis.

However, consensus was reached about three practical actions that should be taken, and these set the standard for how venereal cases would be managed from then on. The first was to remove all venereal patients to isolation hospitals, and it was suggested these could be in ships moored off the Egyptian coast. The second was to send syphilitics, and perhaps all venereal cases, back to Australia for more effective care there. The troopships used could be temporary isolation hospitals, with treatments continued during voyages. The third recommended action was to continue the education program about the diseases that had been started by Major Barrett. He could distribute a new pamphlet about venereal disease and arrange regular lectures by medical officers.

Inevitably, when the delicate question of prophylactics arose, there was a division of opinion. Howse was sceptical, while some others were mildly supportive. Barrett’s was the only voice heard that was strongly in favour; he argued that prophylactics ‘had been absolutely proved to be of value’ when he had run a public-health campaign in Victoria to combat VD. To the Heliopolis conference, he made a radical proposal: special depots for soldiers on leave in Cairo should be established, ‘because at many of the brothels there were no conveniences for obtaining personal cleanliness’. Without spelling it out, he was recommending that Calomel ointment and Argyrol jelly be made freely available to men visiting brothels; he had already been handing them out to staff at his hospital. The Heliopolis conference could not, of course, reach agreement about this, but it was suggested that, when the doctors returned to their hospitals, further research could be made by those interested.

The day after, Barrett arranged for a parade to be held of everyone working at his hospital, during which they were medically examined. Only one was subsequently suspected to have VD. In a report sent to Colonel Howse that afternoon, Barrett revealed that staff at the hospital had been warned about brothels, but, if they insisted on going, they were to take Calomel and Argyrol provided by him free of charge. He reported that the results of the parade confirmed that their use had practically eliminated venereal disease from his unit.

Lieutenant Colonel Arthur White, commandant of the 2nd Australian Stationary Hospital, also arranged research about prophylactics after the conference. In February 1915, White’s hospital was treating hundreds of venereal cases, so he had 540 infected men interviewed. The results showed that only in 51 cases had men not used protection at all. The majority had unsuccessfully used a variety of prophylactics, including Calomel ointment and syringing. Only four infected men had used rubber condoms: three had burst during intercourse, and, although the other had not, the man had become infected with gonorrhoea, anyway.

Major Barrett continued to argue that Calomel and Argyrol were effective if used exactly according to the detailed instructions meant to be given. However, the Australian army in Egypt in 1915 could not seriously countenance any plan to issue kits and instructions, even though hospital admission rates remained high well into 1916 — when they substantially increased. Prevention was an idea before its time, and could only be adopted later, when the AIF was in Europe. The revolutionary changes that occurred there were introduced by Neville Howse himself, who by then was director of medical services for the AIF and a major general. Under his policy, Blue Light kits were freely issued, along with educational pamphlets that, in 1915, Howse had called ‘a waste of time’.

We now come to a doctor at the Heliopolis conference who was not recorded as having said anything, but who was about to become chosen, apparently reluctantly, as the officer who would select the infected soldiers to be sent to Australia. This was Lieutenant Colonel John Brady Nash, second-in-charge at the 2nd Australian General Hospital and a prominent medical practitioner, surgeon, and politician from New South Wales.

A portrait of Dr John Brady Nash made in 1907. (SLNSW)

He had been a doctor and surgeon in the Newcastle area, and also a major figure in the affairs of the Catholic and Irish-Australian communities in New South Wales. He had moved to Sydney in 1900 after being appointed to the NSW Legislative Council. A major in the 4th Irish Regiment of the militia at the outbreak of war, he had decided, at 57 years of age, to take a year off from his political duties to become an AIF medical officer. He had been appointed a lieutenant colonel, and arrived in Egypt on the Kyarra with the 2nd Australian General Hospital. When Brady Nash attended the Heliopolis venereal-disease conference the following month, where he managed to avoid appearing over-interested, he could not possibly have expected that, a few months later, he would be intimately involved with the problem. This came about as a direct consequence of the landings at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915.

Although preparations for military action had been underway since March, the final orders given on 1 April to mobilise the ANZAC force for the Dardanelles campaign caused a re-arrangement of AAMC hospitals in Egypt. It was decided that some would be relocated with the troops to the Dardanelles area, including to Lemnos and Imbros islands, and to Gallipoli to support the Australian attack, while others would remain in Egypt to await casualties.

At this time, with 30,000 AIF troops on the move in Egypt, the recommendations made at the venereal-disease conference at the Heliopolis Palace Hotel were only partly accomplished. There was a plan to remove venereal cases to special isolation facilities, and to send some or all back to Australia. The first had been done, with venereal patients now in isolation wards at a number of hospitals. The second had been started, with some hundreds of infected men sent to Australia and some to Malta. There were still many VD patients in Egypt, and no decisions had been made about them.

However, no one in the AIF or the British army had anticipated the very high casualty rates after the fighting began. On 25 April, the disastrous first day at Gallipoli, 2,000 Australians were killed or wounded as they went ashore and attempted to scale the hills. Over the next weeks, many thousands of British and Australian casualties were sent from the Dardanelles back to Egypt, and this was far more than had been prepared for. Then, at Gallipoli, many soldiers began falling ill with dysentery, influenza, and typhoid, and were also evacuated to Egypt. During May and June 1915, an urgent re-organisation of the hospitals in Egypt was undertaken to vastly increase the number of beds, and all kinds of buildings in Cairo were requisitioned to be turned into hospitals. For example, the 1st Australian General Hospital, which in January had opened at the Heliopolis Palace Hotel with 520 beds, was, by the end of May, a 10,600-bed hospital occupying 11 buildings in the city.

Three members of the NSW parliament on active service with the AIF in early 1915: Sergeant Edward Larkin (left); Lieutenant Colonel George Braund (mounted on the donkey); and Lieutenant Colonel John Brady Nash. (SLNSW)

The time had arrived to remove venereal patients from Egypt. Two days after the landings at Gallipoli, and amid much decision-making in Melbourne brought on by the crisis, Senator Pearce agreed to a request from Cairo that ‘all cases of venereal should be transferred to Australia, since it was urgently necessary to relieve hospital pressure’.10 The ‘venereals’ were to be concentrated at a newly formed isolation-detention barracks at Abbassia in Cairo, and then shipped back to Australia. The barracks was to be an independent command within the 1st Australian General Hospital, located in an old British army building, and guarded by armed sentries. Up to 2,000 beds would be made available, mainly for Australians, but also for infected New Zealand and British soldiers. The Australians were to be given whatever medical treatment they needed before being sent away. Their destination was an old army camp at Langwarrin, south of Melbourne, part of which had already been converted into a small detention barracks for the VD-infected soldiers sent earlier in 1915.

Now a sufficiently senior medical officer had to be found to command Abbassia. When some of the Cairo hospitals had been relocated to be closer to the fighting, Lieutenant Colonel Brady Nash had not been sent with them. Two days after the Gallipoli landings, he received a letter from the surgeon-general of the British army in Egypt, which politely ordered Brady Nash to take charge at Abbassia.

Few Australian doctors or patients associated with venereal diseases in Egypt in 1915 recorded their experiences in writing for posterity. Of the patients, some later wrote to the army, sometimes to complain about mistreatment and sometimes to request secrecy, and their letters are preserved. Of the doctors, apart from Barrett, who wrote copiously on the subject, only Brady Nash has left us with written impressions of his time at Abbassia, in a meticulous diary — the daily entries barely legible, written in his atrocious doctor’s scrawl. He also wrote letters, some to The Medical Journal of Australia, about his experiences. In a report published in September 1915, his appointment to Abbassia was recalled:

The Director of Medical Services called upon [Brady Nash] to take charge of this hospital. Although he felt that this duty was not one for which he was specially suited, he obeyed without murmur, merely pointing out that ‘It is not my job, sir; but if you desire it my best efforts will be put forth to run the show’.

On his first day at Abbassia, at the beginning of May 1915, Brady Nash discovered that he was the sole doctor there. He had no particular training or expertise in diagnosing and treating VD, but had to decide on the methods he would use. For gonorrhoea cases, the patients would be given urethral irrigations of colloidal silver or sandalwood oil. The syphilis cases would receive intravenous injections of Arsenobenzol, and intramuscular injections of Grey Oil, a solution of mercury. The progress of syphilis cases would be monitored using Wassermann blood tests. The lesions, buboes, and sores of syphilis and chancroid on patients’ genitalia were to be destroyed using mercury-chloride ointment, mercury-oxide lotion, or diluted mercury-nitrate acid.

Although he was the officer in charge of a 2,000-bed hospital, Brady Nash was initially allocated just three staff to assist him: a warrant officer, a staff-sergeant quartermaster, and a staff-sergeant dispenser. He discovered that his patients would carry out the treatments on themselves, and that they would also be his medical orderlies. Fortunately, the expected influx of infected men took some time. Elsewhere in Cairo, the first 261 infected men to be sent to Australia following Senator Pearce’s approval were being collected directly from hospitals and taken by train to the Suez Canal, where they were loaded onto the troopship Ceramic. On the day that Brady Nash started at Abbassia, the Ceramic left Egypt for Melbourne.

Two days later, the first two patients were admitted to Abbassia; from then, the number of admissions rapidly grew to hundreds. It was discovered that many men being admitted had just arrived from Australia — they had been infected shortly before they embarked, or shortly after they arrived. Over the following months, a hospital population crisis was averted by discharging patients who showed signs of having been cured, or by sending large batches of Australians to Melbourne. Despite the sweeping plan Senator Pearce had approved, not all the Australians admitted to Abbassia would be automatically shipped away; some were discovered to not be infected, and others were cured. It also turned out that stories inmates had heard about their being sent home in disgrace as a punishment were not entirely true; the decision to send a man home would be based mostly on an assessment of his likelihood of recovery.

In May, Brady Nash was joined at Abbassia by a young doctor who would be his principal assistant. Captain Harold Plant was young and single, and had been a resident doctor at the Brisbane Children’s Hospital when he joined the AIF in 1914. Assigned to the 1st Australian General Hospital, he had left Brisbane on the Kyarra. He hadn’t been sent to Gallipoli, and was still with the hospital in Cairo when ordered to help Brady Nash.

Tents pitched for patients staying at the VD detention barracks at Abbassia in Cairo. The immense daytime heat of the Egyptian summer in 1915 made these very uncomfortable to live in. (Barrett and Deane (1918))

A month after Abbassia opened, Brady Nash had to select the first group of patients to go to Melbourne. The Australians in Abbassia wanted to get out, but not to be sent to Australia; and, when selections were underway, some men pleaded to not be sent, or attempted to escape. Brady Nash decided that his judgments would be based on an assessment of the severity of a man’s infection, especially if multiple diseases were present. Some of the men had been carrying their infections for weeks, even months, before treatment had commenced, and their diseases had developed to an advanced state. If a cure could not be achieved in a reasonable time, the man was to go to Langwarrin.

For the first selection, Brady Nash chose 111 men. They were taken to Suez, under guard, on 9 June 1915 to be loaded aboard the Kyarra, which was about to make another of its homeward journeys, this time carrying hundreds of Gallipoli invalids, with a medical team to care for them during the voyage. At Suez, the Abbassia medical records for each VD man were transferred to the ship’s senior medical officer, to be kept up to date during the voyage and eventually delivered to medical staff at Langwarrin.

When Brady Nash wrote to The Medical Journal of Australia at the end of June, he was caring for almost 500 Australian patients. He described how most ‘are placed on verandahs, while extra accommodation is found in tents pitched on the sands. Of the eight wards, one is reserved for men who are acutely ill. This ward contains beds, while all the others have but mattresses on the floor.’ He also explained that almost 200 of the Australians then in Abbassia had fought at Gallipoli, and expressed his admiration for them in spite of the fact that they were ‘under his care for the results of their folly’.

In late June, Brady Nash had to make a second selection of those who would be going to Langwarrin. On 5 July, he sent 131 to Suez when the A70 Ballarat called there from Alexandria with 500 Gallipoli invalids on board. During the following weeks, the number of Australians at Abbassia rose to 550, then 609, and then 658. In early August, when he had nearly 700 patients, Brady Nash selected 414 to go to Langwarrin. This large group was taken to Suez and loaded onto the A17 Port Lincoln, which had just arrived, almost empty, from Alexandria. Brady Nash wrote in his diary that the men he sent ‘were amenable to discipline and gave no trouble’.

On 23 August, he wrote this series of questions in his diary:

Ramsay Smith relieved of his command. Why? Barrett relieved of all his military duties and ordered to confine his energies to Red Cross work. Why? Jane Bell the matron formerly of 1AGH is to return to Australia. Why? A real convulsion. I fear some dirty bad work.

The answers lay in the general troubles at the 1st Australian General Hospital, which had become unmanageable. Complaints were made, some from the doctors, and this came to a head with a storm in a teacup when Lieutenant Colonel William Ramsay Smith, the medical officer in charge of the hospital, had a dispute with his head of nursing, Matron Jane Bell, over nurses’ rosters. Ramsay Smith and Bell were recalled to Australia, and Barrett was also blamed. He also came under fierce public attack for alleged mismanagement of the Australian Red Cross in Egypt. Barrett was also recalled to Australia, but then told he could stay to continue his Red Cross work. He immediately went on sick leave to London, and arranged to be transferred to the British army. In early 1916, he returned to Egypt as a lieutenant colonel in the Royal Army Medical Corps, and worked with it there for the rest of the war.

In late August at Abbassia, Brady Nash made his fourth selection of men to be sent to Australia. On 31 August, he wrote in his diary that ‘300’ infected men left the barracks at eight o’clock in the morning for the trip to Port Suez. There, they boarded the A18 Wiltshire, and after their arrival at Langwarrin at the end of September, these fellows became known as the ‘boys ex-Wiltshire’ — including the five subjects of Part Two of this book.

A month later, Brady Nash dispatched the last shipload of VD men to be sent to Australia in 1915, this time from Suez and again on the Ceramic. This was one of his last duties at Abbassia, because it had been arranged for him to go to the Dardanelles. Thus began for him a very interesting two months of adventures at AIF hospitals on Greek islands and at Gallipoli. In December — and back in Cairo, with his year at the war almost ended — he received orders to take on the position of senior medical officer on the A32 Themistocles, which was about to take Gallipoli invalids to Australia. A few days later, he left Suez, and arrived back in Sydney early in January 1916.

During 1915, 1,344 infected men were returned to Australia from Egypt, and Brady Nash was the doctor who had selected most of those sent. He could not have known as he sent them away that there would be a number of unfortunate incidents involving his former patients on the ships, at Australian ports, and at their destination, Langwarrin. Serious questions would be raised about the risks of sending venereal cases back, particularly after the hospital-accommodation crisis in Egypt was resolved. All of this led to a decision in October 1915 by the Department of Defence, made on the recommendation of the surgeon-general, Colonel Fetherston, to expand the army’s VD-treatment facilities in Egypt and handle all cases there.

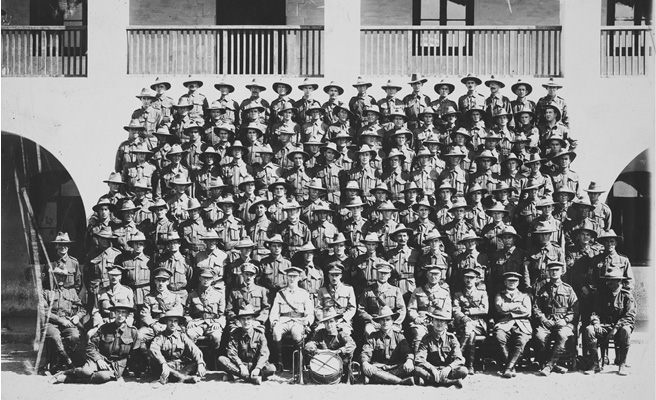

The staff of the 1st Australian Dermatological Hospital, photographed at Abbassia in 1916 — all were male. (SLNSW)

The 1st Australian Dermatological Hospital, a new AAMC medical unit specifically for venereal cases, was hastily raised in Sydney. This was commanded by Major William Grigor, a young, newly commissioned medical officer who had been a dermatologist in Macquarie Street. The seven doctors and 100 other ranks of the hospital embarked for Egypt from Sydney on the A61 Kanowna just before Christmas 1915, and, after they arrived in Cairo, took over the detention barracks at Abbassia, which was converted into a proper hospital.

The dermatological hospital remained at Abbassia until August 1916, and, during its first months, the daily totals of patients under treatment far surpassed those during 1915. At the peak of the infections, in March 1916, a record daily average of 1,500 men was being treated. Then, as the re-organised AIF progressively moved its battalions to Europe, the numbers at Abbassia began to decline. By June 1916, there were about 700; in July, 240; and in August, only 100. That month, Major Grigor received orders to pack up the hospital and follow the AIF to Europe.

The dermatological hospital arrived in England in September 1916. It moved into an existing hospital at the British army camp at Bulford on the Salisbury plain in Wiltshire. Over the next three years, there were about 30,000 admissions, and the hospital was still admitting and discharging AIF soldiers until November 1919, a year after the war had ended. Despite Bulford being the largest of the Australian venereal-disease hospitals, it developed a reputation as a place where medical staff who had made mistakes elsewhere in Europe were sent to work without recognition or thanks. It was also never a happy place for the officers and soldiers who were treated there — some for multiple admissions, some for months at a time. The much smaller AIF venereal-disease hospital at Langwarrin became a place of light and learning, and provided positive experiences for patients, but apparently that never happened at Bulford.

The last words in this chapter are mainly about James Barrett. As we shall see, he would have many last words in the coming post-war revelations and debates about VD in the AIF. After he left the AIF in Egypt, Barrett became an assistant director of medical services for the RAMC there, and, in February 1916 he met Ettie Rout, who had recently arrived from New Zealand, leading the New Zealand Volunteer Sisterhood, a group of women to care for New Zealand soldiers.

A 1917 photograph of the New Zealand social reformer Ettie Rout. She is wearing the badge of the New Zealand Volunteer Sisterhood, which she founded in 1915. (Jane Tolerton)

Rout immediately noticed the large number of soldiers infected with VD, and began a vigorous campaign, first in Egypt and then in France and England, for Allied armies to treat the diseases as a medical problem, and not a moral one. She urged that all available preventive measures be used, including properly supervised brothels, and she invented prophylactic kits to be given to soldiers. Rout became famous for her work, and popular among ANZAC soldiers; but, in New Zealand, she was disapproved of, and her name was unmentionable. After she arrived in Egypt, Rout discovered that James Barrett held similar ideas to her own, and the two collaborated. He became the medical expert who helped guide Rout’s safe-sex campaigns, and he also arranged introductions for her to important British officers in Cairo and London, and sometimes to their influential wives as well.

In March 1916, Rout made an inspection visit to the Wasa’a prostitution quarter. This was when venereal infections in Australian troops reached record levels, and, after her inspection, Ettie explained why this was happening in a report that was circulated to senior Australian and New Zealand officers, and eventually to the Australian prime minister. Even though it was now over a year since General Birdwood had become upset about it, and the AAMC doctors had met at Heliopolis to discuss the problem, nothing much had changed in the Wasa’a:

The streets and alleys were filthy with offal and the stenches abominable, but they were crowded with men in Khaki. There were several drinking shops and dancing halls quite open to the streets, and hundreds of soldiers were in these. Outside notorious brothels long queues of soldiers waited their turn. One open door revealed a stairway with lines of soldiers going up and down — in and out. Soliciting and enticing was quite openly carried on. Bedizened and lustful women thronged the streets and doorways, many of them being embraced by soldiers. Doors were open and soldiers could be seen inside the rooms sitting on women’s laps and vice versa.11

For a long time after the war, Barrett re-fought the old battles of 1915 about venereal-disease prophylaxis. He wrote letters to editors, and articles for newspapers and medical journals, and he occasionally spoke at medical conferences. In 1940, he was unapologetic after writing that, during the First World War, the British army was overrun during the German spring offensive in early 1918 because so many British soldiers were in hospital with VD.

In 1916 and 1918, Barrett was mentioned in dispatches for his work in Egypt with the RAMC, and, in 1916, he was awarded the Order of the Nile. In 1918, his wartime service was recognised by King George V: he was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire, and a Companion of the Order of the Bath. With the widespread use of prophylactics and other preventive measures having been approved in the AIF and other armies from 1916, Sir James could now be satisfied that his advocacy of these methods since early 1915 had been proven correct.