CHAPTER FOUR

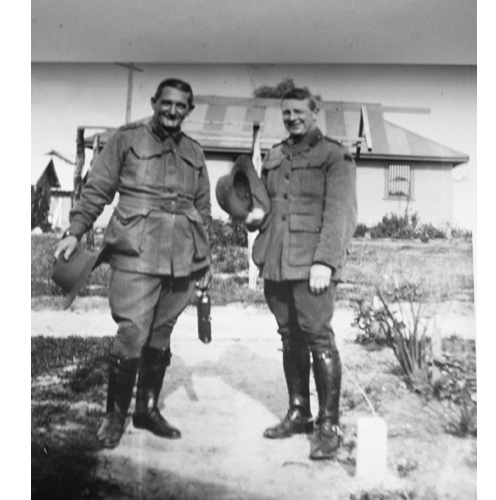

Robert Williams and Walter Conder

the isolation-detention barracks at Langwarrin

When the decision was made in January 1915 to send men with VD from Egypt to Australia, the army was faced with the urgent challenge of finding somewhere to put them. By early February, the first group of patients was heading home on the Kyarra, and more were following, so there was no time to lose. Because of the contagious nature of the diseases, and the public terror of them, the hospital would need to be akin to a detention barracks, able to hold men in complete isolation. Given the urgency, it would need to use existing facilities in an army camp.

If the isolation barracks were to be in a camp anywhere near civilians, agreement would need to be reached to allay their fears. The difficulty of achieving this was demonstrated when a proposal to establish it at the Liverpool camp near Sydney was refused by the NSW government because of local complaints. Even if permission had been given, it is unlikely that men with VD would have been tolerated for long at Liverpool. Throughout 1915, the citizens of Sydney were repeatedly made aware that there was much trouble at this camp, including drunken riots, which led to a royal commission to examine its deficiencies.

Professor J. Laurence Rentoul of Ormond College, Melbourne University. In 1916, Rentoul became a chaplain-general in the AIF. (NLA)

Another possibility was the big camp at Broadmeadows, near Melbourne. It had been opened in great haste in August 1914 to process Victorian recruits to the AIF, and in early 1915 was still a maze of dusty tents. There were other problems at Broadmeadows, as well, preventing it from being considered as a place to put men with VD. Public concerns were initially aroused by accusations made by a Melbourne Presbyterian, Professor J. Laurence Rentoul, who announced that Broadmeadows was a ‘camp of evil’. He was referring to drinking, gambling, circulation of pornography, and prostitution, which, according to Rentoul, went on quite openly. Then, during autumn wet weather in 1915, the poor drainage and leaking tents caused an outbreak of meningitis, and some recruits died. As a result, a decision was made to establish the main Victorian recruit-training camp at Seymour, 100 kilometres north of Melbourne, with Broadmeadows supposed to be gradually scaled down in importance.

A rudimentary field kitchen at a Victorian militia camp at Langwarrin in the late 19th century. The bell tents in the background were still being used in 1915 in the detention enclosures for enemy aliens and VD-infected AIF soldiers. (SLV)

There was, however, another place near Melbourne that seemed suitable. Three decades earlier, the Victorian colonial government had reserved for military use a large area of unused land at Langwarrin on the Mornington Peninsula. A rudimentary camp was established with a parade ground and tent lines, and roads named after military heroes like Napoleon, Wellington, and Marlborough. Bushland was cleared to make way for firing ranges, and pasture for military horses. A railway station was built, and, in 1888, there was a failed attempt to establish a township called Aldershot, after the British army camp in Hampshire.

Although regularly used by the Victorian colonial militia, the camp was never properly developed. In 1899, when the Boer War began, it received hundreds of volunteers for Victorian contingents, but they were very disappointed with the leaking tents, poor sanitation and water supply, and lack of proper kitchens and messes. After Federation in 1901, the Australian government took control of the camp, and it continued to be used by militia units and for the annual camps of army cadets from Victorian schools.

After the outbreak of war in 1914, it was decided that people of German, Austrian, and Turkish descent would be interned as enemy aliens, and those in Victoria would be sent to Langwarrin. Hundreds of people were rounded up and interned in a newly built barbed-wire compound; they slept on the ground in old army tents, and water had to be brought by train and carted in. An officer of the Victorian militia, Major Archibald Lloyd, was in charge and commanded an armed militia guard. In April 1915, an escaper was shot and wounded when the militia fired at him; the same volley of shots killed another internee with a ricocheting round. By May, over 400 aliens lived at Langwarrin, and the numbers steadily increased.

In early 1915, because nowhere else could be found, it was decided that men with VD sent from Egypt would be put in a detention barracks at Langwarrin, next to the internee compound. A guarantee was given to the Victorian government that they would be completely isolated from the civilian population outside. It was assumed the barracks would be temporary and for not many men, so a small barbed-wire compound was built, tents were erected, and some alien internees were employed as cooks. The compound was also placed under the control of Major Lloyd and his militia guard. When the men brought on the Kyarra, Moloia, and Ulysses arrived, they, like the aliens next door, were required to sleep on the ground in old tents; even worse, because of the water shortage, there were no bathing facilities for them at all.

In March 1915, the first medical officer began making daily visits from Melbourne. He was Dr Whitfield Henty, a young general practitioner in Armadale who was a captain in the AAMC Reserve. After two months, he was sent to Egypt with the 3rd Australian General Hospital. His brief period at Langwarrin, brought to an end with an overseas posting, was typical of doctors who worked at the camp from then on. It was difficult to find doctors to work there at all, and the rapid turnover of those sent added to the chaotic conditions that soon developed.

After the Gallipoli landings in April 1915, the defence minister, Senator Pearce, approved sending all venereal cases from Egypt to Langwarrin. After the first group of 261 arrived in May on the Ceramic, the camp struggled to house and feed its growing population of aliens and soldiers. What appeared to be a solution was a decision made by the defence department to concentrate most enemy aliens in Australia at a camp at Holsworthy, near Sydney. It took a long time to clear them from Langwarrin, and they had still not been moved out when, in July, the Kyarra delivered another 111 men from Egypt, followed by another 131 on the Ballarat the next month.

In mid-1915, there was a change of the commandant of the 3rd Military District, which covered Victoria. A suitable senior officer was needed to replace Colonel Robert Wallace, who had become ill. In July, Senator Pearce chose Colonel Robert Williams, initially in an acting capacity; later in 1915, he was confirmed in the role and promoted to brigadier general. His appointment as Victoria’s military commandant would be of great significance for the thousands of AIF men eventually sent to Langwarrin.

Brigadier General Robert Williams. (AWM)

As a young man, Colonel Williams started his working life as a teacher in Ballarat, then changed careers to become a journalist and the editor for The Ballarat Courier, and later became the town clerk of Ballarat West. He had joined the militia in Ballarat, and rose to become colonel-in-charge of the 2nd Victorian Infantry Brigade. In July 1915, he was aged 60 and had retired from military duties when he was suddenly recalled by Senator Pearce. Among the assignments of highest priority given to him was proper organisation of the overcrowded isolation barracks at Langwarrin.

His first challenge was finding doctors to work there. Major Andrew Grant, an elderly GP from Dandenong, had been making regular day visits, but had recently stopped. He had been accused of releasing an inmate before the man was cured; the resulting inquiry revealed that if a man infected with gonorrhoea drank copious quantities of water before taking a urine test, the result could be clear of pus threads. Later, and despite better methods for VD testing, other Langwarrin doctors got into trouble for releasing men who were only apparently cured.

In August 1915, Colonel Williams found two new doctors to replace Dr Grant. Dr Arthur Morris was a prominent Collins Street dermatologist in Melbourne, well known (along with his wife) on the social and charity committees of the city. He was not in the army, so, for him to become senior medical officer, Colonel Williams arranged a temporary commission as a captain. Morris was a venereal-disease expert, and appears to have been the first genuine specialist to work at Langwarrin.

He was assisted by Dr James McCusker, a young Scottish GP who had become involved with the AIF in Egypt earlier in 1915. McCusker was sent to Australia as a medical officer on the Ballarat to look after the notorious group of ‘venereals’ on board. After arriving in Melbourne, he joined the AAMC, believing he would be immediately sent overseas. He was made a captain, but was instead sent by Colonel Williams to work at Langwarrin.

In early September 1915, 414 more infected men arrived, delivered from Egypt by the Port Lincoln. AIF recruits with VD were also being sent to Langwarrin, and the overcrowding got worse. Colonel Williams visited the camp to see what could be done. He conferred with the staff, and talked with the inmates about their complaints, which were mainly about loss of pay. By now, most had been without it for months — and for many, this meant they could not get tobacco and alcohol. They knew there were supplies not far away at the pubs in Frankston, and they wanted their pay restored so they could go. Williams gave them a sympathetic hearing, but could not promise restoration of pay, or permit men to leave. After he returned to Victoria Barracks in St Kilda Road in South Melbourne, he told a reporter from the Argus newspaper about some of his experiences that day.

People in Melbourne were intrigued to read a story about Langwarrin. Two weeks later, the Reverend Henry Worrall, a famous and fiery Methodist morals campaigner, labelled the men in the camp who had returned on the Port Lincoln ‘the nameless 400, of whom none of them were wounded or had ever pulled a trigger’. This, the inmates thought, was gravely insulting and wrong, so a protest meeting was held at the camp, led by the Gallipoli men. An anonymous letter that refuted Worrall’s claim was sent to The Argus, pointing out that many of the soldiers in Langwarrin had been at Gallipoli.

In late September 1915, 275 more men from Egypt arrived at the camp. These were, of course, our ‘boys ex-Wiltshire’, as they became known at Langwarrin. They immediately discovered that it was worse than Abbassia, and some thought of trying to escape. Dr Morris and Dr McCusker examined each man and confirmed that a number did appear to have been cured by Captain Alsop during the voyage. Orders were made to send these lucky fellows to the Broadmeadows camp, with pay restored, for drafting to new battalions. Within a month or so, those released as fit for duty from Langwarrin found themselves back at Port Melbourne, waiting to board troopships to take them back to Egypt.

Morris and McCusker also recommended that some of the Wiltshire men be discharged from the army because of their medical unfitness, but not because of VD. These included soldiers with old injuries and defects apparently unrelated to military service. Some of the Gallipoli men were recommended by the doctors to be discharged because of wounds and illnesses acquired in the Dardanelles, and also not because of VD.

A small number of men had their worst fears realised when Morris and McCusker recommended they be ‘discharged–medically unfit–VD’. They had been found to have gonococcal arthritis, chronic gleet, persistent buboes, and other venereal conditions that might prove very difficult to cure. Men from Victoria in this category were transferred to hospitals in Melbourne or Geelong for a final decision. Those from elsewhere were sent from Langwarrin to be processed out of the army in the military district where they originally enlisted. Some sent home in this way chose not to go through with it — they escaped en route, and were posted as deserters.

But most of the men who arrived on the Wiltshire were not recommended by Morris and McCusker for release, or for discharge from the army. They were required to stay at Langwarrin and suffer ongoing VD treatments for many more weeks or even, for some, many more months. Between October 1915 and March 1916, most were released, in ones and twos, apparently cured and fit for duty, with orders to go to Broadmeadows or other camps in Australia to be sent overseas. Even so, about 40 of these fellows never made it to their destination; with pay once again in their pockets, they disappeared shortly after leaving the camp, and were also posted as deserters.

Wiltshire men who had to remain at Langwarrin would soon have to make space for hundreds more brought from Egypt on the Ceramic in October. There were now about 1,000 men with VD living in terrible conditions and unable to know how soon they would leave. Most had been without pay for a long time, and what especially galled them was the camp guard of militiamen, who had not volunteered for overseas service, and who stood between them and the world outside.

The frustration was bound to boil over, and it soon did. The first and largest breakout from Langwarrin happened on a clear spring night on 19 October 1915. During the day, Major Lloyd had refused a demand by some of the men to go to Frankston, but they decided to go anyway. Soon after dark, and in full view of some hapless sentries, a group of inmates approached the fence and threw greatcoats over the barbed wire. They scrambled over and disappeared into bushland. There was then a general rush at the wire by a much larger group — ‘about 100’, one of the sentries reported — and they, too, broke out and scattered into the bush.

When, some hours later, a group of about 50 arrived at Frankston railway station, they forced their way onto a Melbourne-bound train. The stationmaster telephoned ahead, and, by 11 o’clock, military and civil police officers had assembled at Caulfield station to set an ambush. Nineteen escapees were surrounded, there was a scuffle, and handcuffs were used to restrain three. By one o’clock in the morning, the prisoners were in cells at Victoria Barracks. The rest of the men who escaped had vanished into the night, and, the next day, newspapers were reporting that men from Langwarrin were on the loose.

There was a hastily arranged court-martial at Victoria Barracks for those captured at Caulfield. Each pleaded guilty to ‘having broken out of camp in defiance of orders’, and three also for resisting arrest. Major Lloyd and some Langwarrin sentries testified that, during the escape, they ordered the men not to leave. The prosecutor pointed out ‘the necessity for keeping the men in isolation, inasmuch as their complaints might be communicated to others’. Sixteen escapees were given 90 days’ imprisonment with hard labour; those who resisted arrest got 100. However, because all promised to return to the camp and remain there until cured, their sentences were suspended.

The following day, Major Lloyd was sacked by Colonel Williams and replaced as camp commandant. When announcing this to newspaper reporters, Williams also ordered the remaining escapees to give themselves up, and, threatening blackmail, said that ‘their names and descriptions would be published and broadcast’ if they did not. He then went to Langwarrin, had the remaining inmates paraded, and announced the decisions of the court martial. Williams then threatened future escapees with blackmail, and with arrest as deserters. A notice was placed by the army in newspapers, ordering those who had not returned to report without fail or face public shaming.

Some gave up voluntarily, and a few were brought back by police, but there were many still on the run, and their unknown whereabouts caused public concern. In the Victorian parliament, the minister for public health was asked

what steps the Health Department was taking to protect the people of Victoria in regard to the prevalence of venereal diseases, and respecting the escape of soldiers from the isolation camp? It seemed that [Victoria] was being made the dumping ground for all the Australian soldiers that had been brought back from Egypt.17

Soon, another 40 escapees were rounded up and brought before a court-martial at Langwarrin. Some had taken part in the mass breakout, while others had walked out over the following days. Captain McCusker of the medical staff testified that the men on trial were all infected with VD when they broke out. The prisoners were each sentenced to 100 days’ imprisonment, but their sentences were also suspended. Thus, within a week of the mass breakout, many escapees were back in camp with suspended prison sentences hanging over them, and all this news was published in newspapers.

In November 1915, the problems at Langwarrin were raised in the federal parliament when William Kelly, a NSW politician, urged the defence minister to stop bringing venereally infected AIF soldiers back to Australia. He said that better arrangements should be made in Egypt ‘for their comfort’. Senator Pearce assured Kelly that he completely agreed, and also explained that Langwarrin would be closed and the inmates moved to new locations, including to other states. Soon after, Colonel Williams arranged for some NSW men to be sent to Milson Island, an isolation hospital on the Hawkesbury River, north of Sydney. Some South Australians were sent to the Torrens Island isolation hospital, near Port Adelaide, and a small group of Tasmanians was sent to Hobart.

Senator Pearce’s comment in parliament started a rumour that the Langwarrin men would be transferred elsewhere in Victoria. Alarmed citizens of Bendigo heard that their city’s prison was being considered as a destination. The matter was raised in the Bendigo Chamber of Commerce, where it was said that ‘if it were true that the department intended to plant a number of men afflicted with this disease scourge in a large city like Bendigo, and so close to the playgrounds of two of the principal schools, it showed a great lack of consideration for Bendigo and the public health’.

Then, residents on the Mornington Peninsula launched a protest about the nearby presence of venereally infected men ‘at the concentration camp at Langwarrin’. They were also alarmed because soldiers with venereal disease were using the drinking fountains and toilets at the railway station at Frankston. A railways official said that when the army moved diseased men by rail through the station, no one was notified this would happen, and that warnings should be given so that ‘carriages might be set apart for them and subsequently disinfected’.

The breakouts, courts-martial, discussions in parliaments, and newspaper stories led to other consequences. The attention of Australia was drawn to the Langwarrin camp. The army began receiving letters from relatives of men known to have recently returned to Melbourne, enquiring as to the exact whereabouts of their man, and the nature of the wound or sickness he had acquired while abroad. To the horror of some of the men in Langwarrin who returned on the Wiltshire, parents and wives learned where they were, and began arriving unannounced at the camp.

All the troubles at Langwarrin helped make up the mind of Surgeon-General Fetherston that no more infected men should be sent to Australia from Egypt. He recommended that the 1st Australian Dermatological Hospital be formed to take over at Abbassia. Dr Arthur Morris agreed to go with the hospital when it left Australia in December 1915, and he worked with it in Cairo and later at Bulford. His position as senior medical officer at Langwarrin was filled by Captain McCusker, who stayed there until January 1916, when he departed for the overseas service he had been patiently awaiting.

In December 1915, the now Brigadier General Williams might have reasonably expected that his threats to blackmail and arrest Langwarrin escapees should have stopped the breakouts and ended the newspaper stories. But they continued anyway, and he had to announce that another 20 men had been captured after getting out of the camp. Williams arranged a court martial, but this time the sentences were not suspended: the prisoners were transferred to Pentridge Gaol, each to serve 100 days with hard labour ‘such as his physical condition would allow’.

Among the men who broke out of Langwarrin between October 1915 and January 1916 were about 45 who had arrived on the Wiltshire. Most never returned; others were brought before the courts-martial. Within four months of their arrival from Egypt, almost 100 of the Wiltshire boys had escaped from Langwarrin or from the army. Some had been posted as deserters after their legitimate release from the camp; others, after they left illegally. Most were still on the run, and a small number who escaped were caught only to escape again.

Brigadier General Williams visiting the Langwarrin hospital in about 1917. (NLA)

It was a challenge for Brigadier General Williams to prevent men running away. It was also difficult for the camp to be closed or moved. At some point, it became obvious to him that treating men with VD as criminals while trying to force cures upon them was self-defeating. They were being punished enough by the diseases. Something had to be done to make the inmates want to voluntarily stay until they were cured, and then to willingly return to their military duties. Achieving that, however, would require a remarkable change of attitudes in the patients and in the army.

General Williams’ plan to convert Langwarrin from an isolation-detention barracks to a hospital slowly began to take shape from late 1915. He began by disbanding the militia guard and replacing it with the inmates themselves; he started restoring the pay of men who co-operated, and paid them for doing useful work; and he started searching for doctors who knew about the diseases and would stay for long periods. In particular, he needed an unusual type of army officer to take charge of the humane improvements envisioned by him.

It seems General Williams realised that a new commandant would not get the respect of inmates if he was another militia man. He would need to be an AIF officer — perhaps one who had fought overseas. In late 1915, there were not many such officers in Victoria who wanted to run a military backwater like Langwarrin. The man Williams initially found who appeared to fit the requirements was Major Ivie Blezard, then commanding a depot for returned invalids at the Melbourne Showgrounds.

Major Ivie Blezard at the Broadmeadows camp in 1914. (AWM)

Blezard had been in the 7th Infantry Battalion at Gallipoli, only to be shot in his chest and shoulder shortly after the landings. He had been evacuated to hospital in Egypt, then sent to Australia as an invalid. Having recovered sufficiently by November 1915 to resume work, he had been chosen by Williams to run the Melbourne Showgrounds depot, and then in January 1916 as Langwarrin’s commandant.

Very soon, Blezard was in trouble. Although Williams had made concessions to encourage men to remain in the camp — including the restoration of pay — in January 1916, scores of inmates were still walking out. Some never returned, while others wandered off to local pubs and returned when they felt like it. Soon the general was firing rockets at poor Major Blezard, and again threatening blackmail:

I wish you to make all the men who are in the Isolation Camp understand that if men get away immediately on pay being allocated to them, that the pay will be withdrawn. I want you also to make them understand that if men escape from Langwarrin and are captured, I will have them court-martialled and dealt with as deserters should be dealt with. If they are not re-captured, I will make public in the localities nearest their homes the fact that they are deserters from Langwarrin, and that a reward is offered for their apprehension. I cannot permit these leakages to go on further.18

To help Blezard at the hospital, Williams was searching for other suitable officers. His attention was drawn to another ex-7th Battalion man, a young fellow who had also been wounded at Gallipoli and who was now in Melbourne looking for a job that would keep him in the army. Without Williams knowing, this was the officer who would lead the conversion of Langwarrin to a roaring success as a venereal-disease hospital.

Walter Conder, also called ‘Wally’ or ‘Bluey’ Conder, had been born in Tasmania at Ringarooma, near Launceston, by coincidence not far from where Ettie Rout was born. He attended Launceston Grammar, where he became captain of the school and the senior cadets. A freckled redhead with the face of a pugilist, he was in fact a boxer, as well as a wrestler, a rower, and an outstanding Australian Rules footballer. After matriculating, he became a teacher at the school while studying part time at university and also serving as an officer in the militia at Launceston. Just before the outbreak of war, Conder moved to Victoria to teach humanities at Melbourne Grammar, and was subsequently picked to be a junior officer in the 7th Battalion of the newly formed AIF. He left Australia with the first contingent, and arrived in Egypt in December 1914.

Because of the AIF’s troubles with drunkenness and venereal disease, General Birdwood had ordered General Bridges to steer the men into more wholesome pastimes. It had been decided that one of those would be boxing, and it was soon discovered that Lieutenant Wally Conder of the 7th Battalion with an entrepreneurial flair for organising tournaments.

Lieutenant Walter Conder (right) and another 7th Battalion officer, Captain Finlayson, in Cairo in late 1914. Conder’s fondness for animals was evident during his years at Langwarrin from 1916 until 1921. (Museums Victoria)

Walter Conder at the Langwarrin camp in August 1916 after he was appointed to be the commandant. (NLA)

Conder landed at Gallipoli with the 7th Battalion on 25 April 1915, but within hours was seriously wounded. He was hit by four Turkish bullets in his legs, and then by three in his shoulder, paralysing an arm. As he lay wounded, he was seriously concussed when a shell exploded nearby. Lucky to be alive, he became one of the first evacuees from Gallipoli, and within days was back in Egypt in hospital. In June 1915, a medical board granted him six months’ leave to recuperate in Australia, so he left Egypt on the Kyarra alongside other wounded men being sent home and 111 ‘venereals’ being sent to Langwarrin. Back in Melbourne, he began medical treatment, which became protracted. At this point, a future in the army was doubtful, and he had to talk his way through more medical-board hearings to maintain his hopes of being sent overseas again.

In January 1916, that hope faded when, at the age of 28, he was placed on the list of supernumerary officers — meaning his services were no longer required. That month, he was found by General Williams, who arranged for Conder to continue in the army as an honorary lieutenant, with a temporary appointment as the adjutant at Langwarrin. In August 1916, when Ivie Blezard was transferred to a training depot in Melbourne, General Williams entrusted Conder to take charge of the camp, promoting him to honorary major.

The close working relationship between Williams and Conder turned out to be very productive for Langwarrin, and very good for men who were sent there with VD. The hospital became so effective at curing and returning the men to duty completely healthy that it was not closed until 1921. Between 1915 and 1920, about 7,200 men passed through, with most admitted after Conder began to bring about the farsighted plans of General Williams.

In the development plan for the Langwarrin hospital, a great deal of effort was given to improving medical services. The military objectives were made very clear: increase the percentage of patients perfectly cured and returned to military duties, shorten the period of each treatment, and reduce the costs. To do this work, Williams recruited a new group of medical officers who were committed to staying. The doctors realised that, to achieve all the objectives, every aspect of a patient’s health would need to be considered. Men admitted to Langwarrin with VD usually had other diseases as well. Many had badly decayed teeth, and some had oral VD infections. Finally, to reduce the possibility of a man becoming re-infected, his self-regard would need to improve and his attitude to sexual risk-taking would have to change.

Five doctors appointed by General Williams in late 1915 and in 1916 stayed for long periods, each leading an aspect of the medical plan. Captain Mathias Perl developed improved treatments for syphilis by experimenting with combinations and doses of the commonly used drugs. Major Charles Johnson led the development of bacteriological testing, and also experimented with methods for treating gonorrhoea using the salts and nitrates of silver. Captain William Potter, Captain Alexander Cook, and Captain Henry Hunter Griffith were responsible for other aspects.

Major Walter Conder (right), at Langwarrin in 1917 with Major Charles Johnson, the senior medical officer. (NLA)

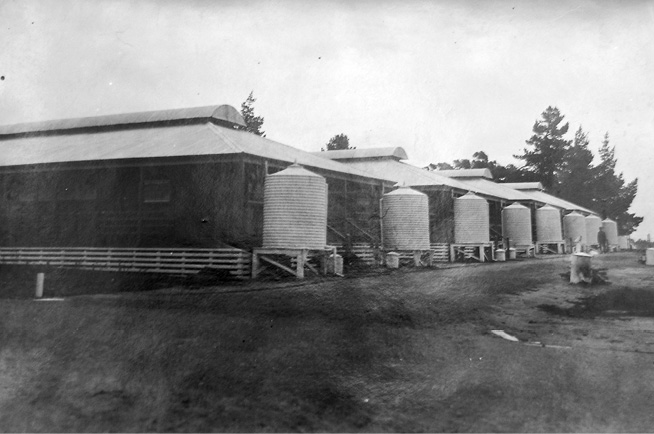

To provide the facilities for medical work, the defence department constructed a hospital near the original barbed-wire compound. A number of modern barracks huts were erected for wards — enough to accommodate 600 patients — and each had beds and a bathroom. Large huts were built for an operating theatre, a treatment room for ‘irrigating’ gonorrhoea patients, a dental surgery, and a dispensary. For the first time since Langwarrin had opened as a military camp, modern kitchens and messes were installed. Accommodation quarters for officers and medical staff were built, and a post office was opened.

To provide abundant water, a bore was sunk and a new pumping station built to deliver the water to an existing reservoir. With a supply of water now available for irrigation, Conder arranged for the grounds of the hospital to be landscaped. Patients made paths, planted lawns and gardens, and cultivated hedges and shrubberies with plants and tools supplied by donors. Under Conder’s directions, about 2,500 trees were planted, including pines, wattles, eucalypts, and English oaks.

A rear view of the new hospital-ward huts constructed at Langwarrin in 1916. The large rainwater tanks were part of general improvements to the water supply made during that year. (NLA)

An ornamental fountain was erected by patients near the main entrance. A circular pond was dug and lined with cement; a pedestal with a circular marble table was constructed in the middle; and a marble statue, in classical Greek style, was installed on top. This was a proud, semi-clothed maiden holding aloft an amphora. When an electric pump was turned on, water flowed from the amphora and trickled down her half-naked body to the pond below. For the men in the camp and visitors entering, the symbolism of this lady of the fountain was obvious. She was Venus, the cause of all the problems and the reason for Langwarrin, but now safely captured to harmlessly delight all who saw her.

The ornamental fountain, built by patients, adjacent to the main entrance at the Langwarrin hospital. The statue is of a partly clothed maiden holding aloft an amphora. (NLA)

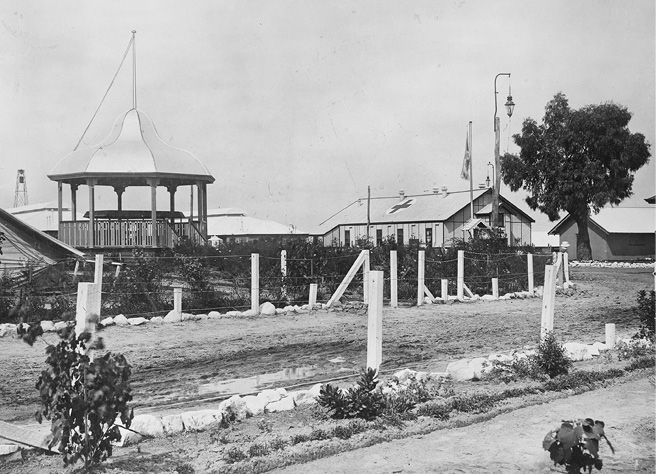

Conder asked for help from donors in Melbourne to make the hospital a comfortable place. He persuaded the Red Cross, the YMCA, the Victorian Racing Club, the Victorian Amateur Turf Club, sports clubs, businesses, and individual donors to provide funds and materials. He persuaded local community groups to overcome their suspicions and become involved. With all this assistance, a shower block with hot water, various well-equipped workshops, a Red Cross concert hall, a bandstand, a YMCA hut, and a canteen were gradually added. A military brass band was formed, using donated musical instruments. Men, women, and children from surrounding communities were made welcome to visit the patients and show interest in them.

The bandstand and Red Cross hut built at Langwarrin in 1916 and 1917. (AWM)

By March 1916, the situation at Langwarrin had sufficiently improved for General Williams to invite the governor-general of Australia, Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson, to admire the results. Sir Ronald had made a visit in December 1915, and must not have been happy. Now, accompanied by the chief of the general staff, Sir Ronald again inspected the camp, and addressed the patients before an audience of local citizens. This time, he complimented the men on the vast improvement, and congratulated the staff for their excellent work.

The main entrance to the Langwarrin hospital in about 1917. The sentry on duty was also a patient. (AWM)

Brigadier General Williams and local children planting trees at the Langwarrin hospital in 1916. (NLA)

By Christmas 1916, Conder could demonstrate to General Williams, in monthly statistical charts he had made, that escapes and absences had practically stopped. Also at Christmas, the governor-general again visited Langwarrin, this time to open some of the new facilities. The Argus reported how he ‘took the salute in a march past of the guard and the men of the camp, headed by the camp mascot (a diminutive pony gaily caparisoned and with tinkling bells) and the camp band’. Sir Ronald compared the deplorable conditions a year before with those now, and said that, in his opinion, Langwarrin was the best military camp in Victoria. He went on to visit Langwarrin often during the war, sometimes accompanied by Lady Munro Ferguson in her role as president of the Australian Red Cross.

How did a camp under threat of closure in 1915 still have thousands of patients until 1920? Although the flow of infected men from Egypt had stopped, there was still a need for a military venereal-disease hospital in Australia. There were various reasons for the continuing demand: AIF recruits became infected before going overseas; infected militia men were admitted; and some of the soldiers invalided to Australia from Europe with wounds or diseases were also infected with VD, as were others repatriated during and after the war. But there was also a reason to do with military requirements. At any one time, the number of AIF soldiers in Europe languishing in hospital with VD was equivalent to the full strength of an infantry battalion. The military and financial costs this incurred meant that Langwarrin was needed to find better, faster, and cheaper cures. If that happened, a man who caught VD might find himself back at the front much sooner than previously anticipated.