CHAPTER SEVEN

Richard Waltham and Harold Glading

the secrets of the dead

Richard ‘Dick’ Waltham was different from most other young men sent back to Australia on the Wiltshire. Most of those fellows were not well educated, and had started working at a young age on farms and in factories as labourers and apprentices. Their parents were not well-off, and had to work hard to provide for their children. Richard, by contrast, was from a well-to-do and prominent family of educated professional people. Nonetheless, soon after his arrival in Egypt in late July 1915, he, too, became infected with VD. He was admitted to Abbassia and, not long after, was selected by Colonel Brady Nash to be sent to Langwarrin.

Richard was born in 1894 at Heidelberg in Melbourne, the youngest child of Joshua and Constance Waltham. In 1867, as a young man of 21, Joshua had immigrated to Australia from Hull in England, and in Victoria became qualified as a licensed surveyor. In 1883, he married Constance Bromby, whose family was also from Hull. As a four-year-old child, Constance had arrived at Port Melbourne in 1858 with her parents and nine siblings; her father, John Bromby, had been invited to be the first headmaster of the Melbourne Church of England Grammar School for boys.

Dr Bromby was 49 when he brought his family to Australia, having had a distinguished career as a teacher and headmaster at prominent English private schools, and as a lecturer at St John’s College at Cambridge University, where he earned a doctorate in divinity. He was also an ordained priest of the Anglican Church, as was his father, and had been a university preacher at Cambridge. In April 1858, he opened the doors of Melbourne Grammar School on St Kilda Road near South Yarra, and for the next 16 years established the culture and traditions of the school. As the clergyman-headmaster, Dr Bromby’s duty was to impart high standards of Christian conduct, which he did with wit, passion, and humour — his captivating personality earned him popularity and respect.

After he retired from the school, Dr Bromby became the Anglican incumbent at St Paul’s Cathedral in Melbourne. He was a leader of the Society for the Promotion of Morality, and an outspoken opponent of alcohol, prostitution, and venereal disease, but never by playing a firebrand preacher role. His elegant sermons about health, happiness, and virtue were prepared in a scholarly way, and he would use charm and wit in their delivery. An obituary in The Argus on his death in 1889 declared that the delightful Dr Bromby had been ‘a rich thinker and fearless defender of the truth’.

So how could a grandson of his, Richard Waltham, become infected with venereal disease in Cairo in 1915, and be shipped back to Australia in disgrace?

When the war began in August 1914, Richard and his mother were living in Perth. The 1890s had been economically depressed times in Victoria, but a mining boom in Western Australia had provided employment on the goldfields for surveyors, so Joshua moved the family to Perth. They settled at Cottesloe, and Constance opened a music school on St George’s Terrace in the city. She was a classically trained pianist: in the 1870s, she had been sent by Dr Bromby to Stuttgart to study at the Royal Conservatory of Wurttemberg, and, on returning to Melbourne, Constance had opened a school in Heidelberg to teach piano and singing. As a boy, Richard went to school at Lemyn College, a private primary school where his mother taught music. He was then enrolled at Guildford Grammar, where he completed his secondary education and experienced his first military adventures as an army cadet. In June 1914, just before the war, his father died. When Constance was widowed, she was 60, and all of her children were adults; Richard was 20, and farming with an older brother at Wanneroo, north of Perth.

Richard enlisted in the AIF in Perth in March 1915, and joined the 28th Battalion, then being raised by Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Collett at the Black Boy Hill camp. On 16 April, the battalion’s first day, Richard was immediately promoted to corporal. This is exactly what would have been expected for a fine young fellow who was nearly six feet tall, intelligent, well educated, and from a good Perth family, and who had some military experience. With his background, he could expect to rise through the ranks, and perhaps to gain a commission as an officer.

Richard Waltham in 1915 after he joined the 28th Battalion in Perth. (AWM)

At the end of June 1915, after training for two months, the 28th Battalion embarked from Fremantle on the Ascanius, bound for Gallipoli. A few weeks later, they arrived in Egypt. During a brief stay at an AIF camp near Cairo, the completely unexpected happened: when leave was granted for battalion members to visit the city, Corporal Waltham caught gonorrhoea. He was one of only a few men to become infected, and, as an NCO, his behaviour was regarded as disgraceful. Very quickly, he lost his rank, was struck from the battalion’s strength, and was sent to Abbassia. Two months after leaving Australia, he was sent straight back by Colonel Brady Nash. On 10 September, when the 28th Battalion went ashore at Gallipoli, Richard was far away in the Indian Ocean on the Wiltshire.

Then, in the midst of this personal tragedy, during the voyage of the Wiltshire, two good things happened to him. The first was that he found a really decent new mate. The second was that his gonorrhoea was apparently cured.

Also on board the Wiltshire during the voyage from Egypt was a 26-year-old soldier from Sydney, Harold ‘Harry’ Glading, and he and Richard became mates. Harold was the son of John Glading, a Cornish immigrant, and Sarah Stapleton, who had been born on a migrant ship bound for Australia from England. John was a builder, and he married Sarah in Sydney in 1871; they went on to produce 11 children. When the war began, Sarah was a widow, and living with Harold and his teenaged brother Walter, or ‘Wally’, at their home, named ‘Glen Eyre’, in Bronte Road in Waverley.

Before the war, Harold had completed an apprenticeship as a printing machinist at The Sydney Morning Herald, and then worked at a printery in the city. He also trained as a member of the Australian Rifles, a militia unit in Balmain, along with his brother Wally. When the war began, Wally immediately enlisted and joined the 1st Battalion. He went to Egypt with the first AIF contingent, and, shortly after landing at Gallipoli, was wounded. In May 1915, his name and his brother Harold’s appeared in a casualty report in The Sydney Morning Herald:

Sergeant Walter D Glading, who is reported wounded, was born in Balmain about 21 years ago. While in camp at Kensington he was appointed corporal. He left with the first battalion, and, soon after arrival in Egypt he was promoted to the rank of sergeant. When Sergeant Glading’s casualty was announced his brother, Harold, aged 23 [sic], enlisted immediately, and is now at Liverpool.

The departure of the A40 Ceramic from Port Melbourne on 23 November 1915. (AWM)

In June 1915, just over a month after he enlisted, Harold departed from Sydney with the 19th Battalion on the Ceramic. When the battalion stopped briefly in Cairo, Harold — no doubt to his horror — became infected with syphilis. He was sent to Abbassia a week after Richard Waltham was sent, the 19th Battalion moved on to Gallipoli, and Harold was left behind in disgrace. When Colonel Brady Nash sent him back to Australia on the Wiltshire, he had been in Egypt for only a month. That was shameful enough, but Harold’s shame was soon worsened when he learned what had happened to his brother Walter during that month.

At Gallipoli, Walter recovered from his wound and rejoined the 1st Battalion at about the time that Harold arrived in Cairo. On 6 August 1915, the battalion entered the fierce fighting at Lone Pine, and, almost immediately, Walter received a gunshot wound to his head. On 7 August, he was evacuated to a British hospital ship to be taken to Malta, but died of his wounds on the ship and was buried at sea. All this occurred while Harold was misbehaving in Cairo; it appears that, at Abbassia, he was given the news of his brother’s fate. Evidently, he was haunted for the rest of his life by what happened to him and to Walter in August 1915.

Thus, when the two unfortunates Richard Waltham and Harold Glading were taken from Abbassia to Port Suez and thence the Wiltshire, they already had rather a lot in common. Their misbehaviour in Cairo had been uncharacteristic and inexplicable; despite all the warnings, each had still made a foolish choice. Because of their pre-war military experience and good character, each had been expected to make a big contribution in his battalion, but both had failed before firing a shot at the enemy. They could not join the fight at Gallipoli, which they were expected to do, and this was a heavy burden, especially for Harold. At Abbassia, they then had the misfortune to be selected to go back to Australia very soon after leaving.

However, Richard and Harold also had some good luck, which helped them avoid the troubles they had expected at home. First, they were not being sent back to their home military districts, but to Victoria, where they were unknown. Second, on board the Wiltshire as she steamed towards Australia, it appears they co-operated conscientiously with Dr Herbert Alsop, and willingly did everything he requested they do for a cure. When the Wiltshire arrived at Port Melbourne, Dr Alsop reported that 70 of his gonorrhoea patients were free of indications of disease, and Richard was among them. At Langwarrin, both men were medically inspected by Dr Morris and Dr McCusker, and they confirmed that Richard was cured, and that Harold seemed to be clear of syphilis. Within a few days, the two mates were out of the camp, with pay restored and orders to go to the Broadmeadows camp.

There, they were both drafted as reinforcements for the 8th Battalion, and were told they would shortly leave from Port Melbourne to join the battalion in Egypt. This was a remarkable reversal of fate for them: in Melbourne, without any fuss, and without their families knowing anything, their immediate pasts were expunged. They had avoided having to take the drastic actions that so many of their Wiltshire mates would soon take at Langwarrin to get back overseas. However, it does appear that Richard and Harold had already invented the excuses they would use if they needed to make their return to Australia seem innocent and logical. Richard’s story would have been that, in Egypt, he had been assigned for guard duty on a ship returning to Australia with men wounded at Gallipoli. Harold’s story would have been that he was one of the wounded men.

In late November 1915, Richard and Harold joined crowds of soldiers and well-wishers on the wharf at Port Melbourne, and then boarded the Ceramic for the journey back to Egypt, and, they thought, to Gallipoli. When the Ceramic reached Western Australia, she joined a convoy bound for Suez, and one of the troopships that Richard and Harold could see steaming with them was the Wiltshire, which had departed from Port Melbourne a few days before the Ceramic.

The 8th Battalion was a Victorian unit that had gone to Egypt a year earlier, and had landed at Gallipoli on the first day. It had suffered serious casualties during the following months; so, on board the Ceramic, Richard and Harold believed that they would soon take the places of men who had been lost at Gallipoli. They could not know that, very recently, Lord Kitchener and General Birdwood had made a short inspection visit to Gallipoli, which resulted in a recommendation, made to the war cabinet in London, to end the doomed Dardanelles campaign. A secret plan was then hatched to quietly withdraw the AIF, and this was put into action within a few weeks. When the Ceramic arrived at Port Suez, Richard and Harold discovered that the fighting at Gallipoli had ended, and the 8th Battalion was in Egypt again.

It remained there until March 1916 — recovering from the pounding received in the Dardanelles, and training fresh recruits who had arrived from Australia — after which it was one of the first battalions to go to France. Richard had again been promoted to corporal, and he went with the battalion to Marseille. Harold followed a few months later, and was promoted to lance corporal. While they were separated, Richard was found guilty of disorderly conduct and, for the second time in his military career, was reduced to the ranks. Richard and Harold were both assigned to B Company, and, when the 8th Battalion moved to front-line trenches near the village of Pozieres in northern France, they went together.

Here, in July 1916, they had their baptism of fire. As soon as the battalion arrived, it came under heavy attack from German artillery; for weeks, exploding shells blew men to pieces and buried others in collapsed trenches. One Friday night in August, the battalion was ordered to attack across no-man’s-land and capture enemy trenches. A thunderous British artillery barrage, intended to clear their way, opened fire, and the night sky was lit up by muzzle flashes and bursting shells. The Australian infantrymen gamely advanced, but the barrage had not weakened the German defenders, and the diggers were forced back by ferocious gunfire. The Australians tried again and again, but they were always beaten back. The attack ended in failure.

The 8th Battalion now had many wounded and dead scattered across the battlefield. When Richard and Harold and their B Company mates returned to the Australian trenches, they learned that two of their young officers, Lieutenant William Doolan and Second Lieutenant Reginald Dabb, were lying wounded somewhere in no-man’s-land. Volunteers would have to go out, find them, and bring them back.

Battlefield rescues after failed attacks were hazardous undertakings. Although German gunners sometimes held their fire if they could see that rescues were underway, rescuers could easily be shot in the confusion of a night battlefield. One night, three weeks earlier at Pozieres, in another battalion, Sergeant Claud Castleton was single-handedly carrying wounded men to safety when he was shot dead; he was awarded a Victoria Cross for his selfless courage. The essence of the legendary mateship of Australian diggers was founded on a willingness to rescue their friends after failed attacks, whatever the cost.

So now, in the middle of the night of 18 August 1916, it became the duty of Richard Waltham and Harold Glading to go to the rescue of their young officers Doolan and Dabb, or any others they could find. Once again, they went forth from the B Company trenches. This time, Richard was struck in the head by flying metal — it is unclear if it was a bullet, a shell, or shrapnel — and killed.

Constance Waltham discovered none of the details of what had happened from the brief, sad casualty telegram she received. For this refined, sensitive woman, the loss of Richard was unbearable, and we know her thoughts returned again and again to him for the rest of her life. Her father had been a theologian at St John’s College at Cambridge, and he would have understood the magnificence of what his grandson had done at Pozieres. It was through the revelations of St John that the spoken words of Jesus Christ had been recorded, to be later expressed in the poetic language of the King James Bible: ‘Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.’

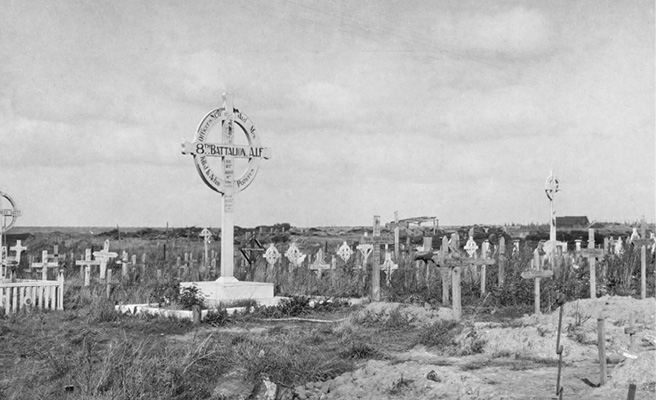

At a time after the battle, Richard’s body was recovered and identified from the little identity disc strung around his neck, and he was buried in a temporary cemetery for 8th Battalion dead near Pozieres. Later, it was discovered that Lieutenant Doolan had also been killed, and he was buried there, too. The cemetery eventually held 81 dead men, including 25 killed in the three failed night attacks of 18 August; by the end of the fighting at Pozieres, AIF cemeteries there held nearly 7,000.

The main AIF cemetery at Pozieres, showing the large memorial to 8th Battalion men killed in the months of July to September 1916. (AWM)

Also after the battle, it was learned that Second Lieutenant Reginald Dabb was one of a number of 8th Battalion men who had been taken prisoner. For most of the night, he had lain on the far side of no-man’s-land, his thigh fractured by machine-gun fire. He was recovered by German rescuers and evacuated to Germany, to a reservelazarett at Berg-Kaserne in Westphalia, a military hospital where his smashed leg was amputated. A few weeks later, he died of his wounds, and was buried in the Haus Spital Prisoners of War Cemetery in Munster.

Lance Corporal Harold Glading survived the night of 18 August 1916 at Pozieres. He was still with the 8th Battalion a year later when, during the Third Battle of Ypres, he received severe shrapnel wounds in his upper right arm. Harold was evacuated to a British military hospital at Birmingham in England, where he underwent a number of operations to remove pieces of shrapnel. Like so many wounded diggers who were evacuated to England, Harold used his reprieve from the war to contemplate his future. In the hospital at Birmingham, he decided it was time for a change. After he was discharged fighting fit, he requested a transfer to become an AIF machine gunner, and, in January 1918, he joined a training brigade. On the Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, Harold learned to use the Vickers heavy machine gun, and, after he qualified, was sent back to France. At the vast Etaples depot of the British Expeditionary Force, Harold joined the 25th Australian Machine Gun Company. He was then involved in the fighting at Villers-Bretonneux to hold back the German spring offensive, and continued to serve throughout 1918 as the Australians achieved one startling victory after another, until hostilities ceased in November.

In April 1919, when Harold was about to return to Australia, he was examined medically by AIF doctors, who found nothing wrong with him. Accordingly, following standard procedure before returning home, he signed a form stating he had no disabilities from his war service. He was then repatriated to Sydney on the Australian passenger steamer Wyreema, arriving home in June. There, he had a final medical examination, which again found that his health was good, although it was noted that he was slightly deaf in one ear. In July 1919, Harold was discharged from the AIF in Sydney. He had not applied for any repatriation benefits, except for temporary financial assistance until he found work.

In Sydney, Harold resumed life with his mother, Sarah, at ‘Glen Eyre’ in Waverley. He was now 31 years of age, but still single, and he remained unmarried for a very long time. He quickly found work at a printing company in the city, and also became a partner in a printing business in Randwick. He received a British War Medal and a Victory Medal in the mail, for his service in France from 1916 until 1918, and was also sent a 1914–15 Star for his month in Egypt in 1915. In 1924, an opportunity arose to move to a country town, and for the next 13 years he supervised the printery at The Muswellbrook Chronicle. The news of his joining the newspaper was published in it, with a reference to his war service:

Mr H E Glading, for many years on the staff at Messrs. Turner and Henderson’s printing works in Sydney, has joined the staff at the ‘Chronicle’ office, succeeding to the position of overseer. Mr Glading comes to Muswellbrook with splendid credentials as a first class printer. He is a returned soldier, having spent four years abroad with the AIF, serving in Gallipoli and France.

In Muswellbrook, Harold became very involved with clubs and organisations. He was a champion lawn bowler, a committee man of the local RSSILA and the School of Arts, and a member of a lodge. In 1937, in an unexpected change, he left Muswellbrook to become the licensee and proprietor of the Metropolitan Hotel at West Wyalong, in the central west of New South Wales. This did not last long, and he sold the hotel and licence and moved back to Sydney.

Some time after his return to Australia in 1919, Harold had communicated with Constance Waltham, the mother of his dead friend Richard Waltham. Constance was Richard’s next of kin, and, in this role, she was a diligent guardian of his memory. At the time of his death, she was living in Melbourne, and she placed a notice in the ‘Died on Service’ section of The Argus, describing ‘Corporal Richard Waltham’ as the ‘youngest son of Constance and the late J. F. Waltham, grandson of the late Dr Bromby.’ More death notices for him were then placed by his sisters in Western Australian newspapers; each of the notices for Richard was just one among dozens for young men killed at Pozieres. For a few years, on the anniversary of his death, in-memoriam notices for him were also placed in newspapers in Melbourne and Perth.

As was the case with other next of kin of soldiers who were killed, the army provided Constance with very little information about Richard’s life in the AIF, or the circumstances of his death. The only information she received were disconnected items in brief letters from the army. As a result, what she understood to have happened was in a number of ways quite different from the much more detailed version held by the army in Richard’s service records, to which she had no access. In the version of events apparently in Constance’s mind, Richard left Perth in 1915 as a corporal in the 28th Battalion, and was killed in France in 1916 as a corporal in the 8th Battalion. It seems she was proud that he held the rank, and her letters to the army always referred to him as a corporal. Constance had no way of knowing that he had been demoted in Cairo in August 1915 when he became infected with VD; or that, in France in 1916, Richard had again lost the rank because of misconduct.

In February 1917, Richard’s death certificate was sent to her by the army. This came with a blunt letter, the contents of which must have come as a surprise:

It is recorded this soldier reverted to the ranks on 8 August 1915. There is no report of any subsequent promotion, and the cable announcing his death and Army Form B 2090A (Field Service Report of Death) each refer to him as ‘private’.

In 1918, Constance received in the mail the little identity disc that Richard had been wearing at Pozieres. In 1921, she received Richard’s 1914–15 Star, but would not have known it was just for his brief visit to Cairo in 1915. In 1922, she was asked to provide some details about Richard for the register at the Pozieres British Cemetery in France; in another letter, she was given the location of his grave. In 1923, she was sent Richard’s Victory Medal, British War Medal, and a Next of Kin Memorial Plaque, which was a medallion issued by the British government that came with a printed message of thanks from the King.

In 1919, Charles Bean was appointed Australia’s war historian, and in the 1920s was kept busy writing The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Before his appointment, Bean had suggested that, as well as making a war history, a national ‘war memorial and museum’ should be erected in Canberra, and this was approved. The memorial was to have a roll of honour listing the names of AIF soldiers killed in the war. To obtain more information about each of the dead, a short questionnaire was sent to next of kin, and, in 1922, Constance Waltham received one to complete for her son.

The questionnaire required a respondent to provide information that many could not have known, including the place where the soldier had been killed, and other military details. For example, Ernest Dunbar’s father, Charles Dunbar in Scone, could not provide some details about his son Randolph, who had been killed at Fromelles in 1916. No one had ever told him the circumstances of his son’s death. Next to the item ‘Place where killed or wounded’, Charles Dunbar wrote, ‘In France — all I know’. The only way that the next of kin could complete the questionnaire thoroughly was to consult someone who had seen what had happened, and evidently Constance Waltham found that witness in Harold Glading.

We do not know exactly when Harold and Constance came into contact, or how Harold provided details about her son’s army career and his death at Pozieres. It is clear that Harold was a loyal friend to Richard, and that he protected Constance from upsetting truths about him. He gave only information that she might like to know, and this was recorded for posterity on the questionnaire she filled in. Next to the item ‘Place where killed or wounded’, she wrote with precision, ‘Martinpuich nr Pozieres’. In the section ‘Any other biographical details likely to be of interest to the Historian of the AIF, or of his regiment’, Constance wrote what she had been told by Harold Glading:

Left W.A. as Corporal on 9/6/15 in 28th Battalion. From Egypt returned as Corporal on board troopship with wounded soldiers to Victoria. At own request transferred to 8th Batt. Killed in night raid. Struck in forehead by shell while assisting to carry Lt. Dobb [sic] (wounded) to safety. Entered firing line 1 June 1916. Lt. Dobb died of wounds, while prisoner.

To the question that asked for the names and addresses of any other persons who might provide further information, Constance wrote:

Harold E. Glading, late of A.I.F.

‘Gleneyre’ [sic], Bronte St., Waverley, Sydney, NSW.

We know it is true that Richard was killed at Pozieres while attempting to recover wounded men after the failed night attacks of 18 August 1916. It is not possible, however, to verify a detail: was he attempting to carry Lieutenant William Doolan, or Second Lieutenant Reginald Dabb, or somebody else from the battlefield that night? The War Diaries of the 8th Battalion and 2nd Brigade provide no corroborating information, nor do the Red Cross files for the three men. In an 8th Battalion history published in 1997, no connection is made between Richard’s death and the attempted rescue of Dabb, although descriptions of their fates appear in consecutive sentences.

In 1936, when the 20th anniversary of Richard’s death was approaching, Constance sent a letter to the army and provided more of her version of his army career. We cannot know if she was aware that this was the story that Harold and Richard had invented to conceal why they returned on the Wiltshire.

… after being in Egypt for a time (1915), left Egypt as a corporal of a guard of 12 men on board a troop ship conveying wounded men from Gallipoli to Victoria. My son made an intimate friendship with one of the wounded men, H. E. Glading. He was granted permission in Melbourne to change his unit and left with H. E. Glading for Egypt in the 8th Battalion.

Constance believed that her son’s war service had been exemplary and that he had been killed in heroic circumstances. She could be deservedly proud, and live her remaining years knowing he gave his life while attempting a battlefield rescue. In December 1943, she died at Subiaco in Perth. Constance was 92, and was survived by a large extended family, including ten grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

Harold Glading’s decision to pretend he had been at Gallipoli appears to have been made soon after he was admitted to Abbassia in August 1915. What happened in Cairo must have seemed so shameful that it would need to be concealed for the rest of his life. His catching syphilis was terrible enough by itself, but it had also stopped him from going to Gallipoli, meaning he hadn’t even been fighting for his side when his brother Walter was mortally wounded at Lone Pine.

Almost 20 years had passed after Harold’s return from the war when he finally married. He was 49, and his bride was 34; they married in 1938 at Campsie Congregational Church in Sydney. He had first met Alice Felecia L’Homme in Sydney in 1926, when she was just 22, and it appears their relationship resumed in the 1930s after Alice, still single, was transferred to Marcus Clark’s department store in Newcastle, not far from Muswellbrook. Alice had been born in 1904, at Milton, on the south coast of New South Wales, near Ulladulla, where her father, Alphonse L’Homme, was a watchmaker. An immigrant from France, he had married a local, Mary Knapp, in Milton in 1899.

Soon after Harold and Alice became married, they started a new life at Belmont, a holiday resort on Lake Macquarie, north of Sydney, where they opened a small mixed business. But not long after she started living with Harold, Alice became aware that he was frequently ill. His deafness was noticeable, and his right arm, which had been wounded by shrapnel at Ypres often caused him pain. By 1940, Harold’s nosebleeds, vomiting, and headaches so alarmed her that she insisted he have a full medical check. To her surprise, this revealed he had serious heart diseases, the kidney disease chronic nephritis, and diabetes. The doctor decided that Harold’s poor condition at such a young age must have been related to his war service. He recommended that Harold apply for repatriation benefits to cover the costs of medical care. Again to Alice’s surprise, Harold refused to do this — because, he said, of his ‘pride’.

They struggled on at Belmont with the mixed business, their marriage produced no children, and Harold’s health became progressively worse. By the 1950s, he was virtually an invalid, so, in 1956, they sold up and moved to Ulladulla, to live at a house called ‘Stray Leaves’ in St Vincent Street. In August 1958, at the age of 69, Harold died at Milton-Ulladulla hospital as a result of coronary and artery diseases, and diabetes. He had lived his last years bedridden, and Alice had spent almost all their married years devoted to his care.

In 1963, she made a claim to the Repatriation Commission for a war widow’s pension, believing the diseases that killed Harold were caused by his war service. However, to satisfy the commission’s stringent requirements, Alice needed to produce irrefutable evidence. She was amazed to discover that, despite her providing what she thought was clear proof, her application was rejected. She was told that, in all the years since Harold’s discharge from the army, he had never applied for the benefits due to someone who was suffering war-related illness, and that the diseases he had died of were caused by old age. For the next six years, Alice exhausted every avenue of appeal to have the decision reversed. During this process, and without Alice knowing, the Repatriation Commission requested the records for Harold covering his treatment in 1915 for an unstated disease. For reasons unknown, they were never provided; perhaps they were lost. The records contained notes made by Captain Plant at Abbassia and by Captain Alsop on the Wiltshire describing the toxic treatment given to Harold, and the fact that it was for syphilis.

Nine years after Harold’s death, an event occurred that caused one of his secrets to be revealed to Alice — and she could not believe it. On 25 April 1965, Australia commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Gallipoli landing, and many large ceremonies were held. In 1967, the prime minister, Harold Holt, announced that a special commemorative medallion would be issued to ex-soldiers who were at Gallipoli, or to the families of those who had died. Alice wrote from Ulladulla to the army department, requesting a medallion on behalf of her late husband. In her letter, she provided, as proof of his Gallipoli status, a brief summary of what Harold had told her:

Corporal Harold Ernest Glading.

No. 1372 19th Battalion

No. 3975 25th Machine Gun Coy.

Enlisted 14/4/1915 Embarked 25/6/1915

Served at Gallipoli & France

From this, we learn that Harold had told Alice he was at Gallipoli, and that he had been a member of the 19th Battalion. She could not know he was in the battalion for just a few months; had he not gone to Abbassia, it would have taken him to Gallipoli. Inexplicably, not included in Alice’s summary was any mention of his membership of the 8th Battalion, which Harold joined in Melbourne after leaving Langwarrin; he was with it for two years, and at Pozieres and Ypres. Why had he not mentioned this to Alice?

She received a reply informing her that, according to the records, her late husband had not been at Gallipoli, and that, consequently, her request for the medallion was denied. Alice was incredulous. She wrote again, challenging the decision, and started a back-and-forth correspondence with the army department. She offered a ‘historical extract’, which purportedly proved that Harold had been at Gallipoli, and said that she possessed Harold’s ‘Gallipoli medal’ — but what she described was his 1914–15 Star.

Her letters created a quandary for the army: this was a sensitive matter, and a truthful explanation could be upsetting to an elderly widow. Eventually, a colonel prepared a detailed internal report showing why it was impossible for former Lance Corporal Glading to have served at Gallipoli. This rebutted the ‘proof’ that Alice supplied, and included minute calculations of the exact timings of Harold’s arrival in Cairo, his infection, and his departure from Egypt. The truth was contained in one sentence:

It would be too much to expect a soldier whose unit went to Gallipoli to explain that he did not go because he was hospitalised with VD.

The report concluded that, ‘In view of the official evidence, we cannot but again reject the widow’s application.’ Despite this, we know that Alice still firmly believed it was all a mistake, and that everything Harold had told her was true. We do not know if she ever learned anything more by the time she died at Ulladulla.

Richard Waltham and Harold Glading were not the only men who were sent from Egypt to Australia in 1915 on the Wiltshire and later used excuses to conceal the real reason for the trip. There were plenty of other fellows who later pretended they had been guards on the ship, or had been at Gallipoli when they were not. Some also pretended that their 1914–15 Star was a ‘Gallipoli medal’. There were other relatives of Wiltshire men who also applied for a Gallipoli medallion on behalf of their man, and who were surprised to discover his secret.