CHAPTER EIGHT

Albert Crozier and Michael Willis

just a silly streak — he was young at the time

Albert Crozier was born in Sydney, the youngest child of Alice and Robert Crozier, who was a horse-cab proprietor. The family lived close to the city at Forest Lodge, where Bert was raised with his brothers, Will and Reg, and sisters, Myra and Elsie. The family was not well off, but Alice and Robert Crozier were caring parents who ensured that their children were properly educated to read, write, and do arithmetic at a commendably high standard. Each of the boys started working quite young — Will in the printing trade, and Reg and Bert in the leather-footwear industry. When the war began in 1914, Bert had risen in the shoe factory to be a ‘bootclicker’, an expert at cutting as many sets of boot and shoe uppers as possible from a sheet of leather, one of the most skilled and highly paid jobs in the industry.

When he first volunteered for the AIF at the Liverpool camp in December 1914, Bert was 21, and the first of the Crozier sons to try to enlist. He was a wiry fellow but short, and this caused a problem. The minimum height for joining the AIF at the time was five feet six inches, but Bert measured five feet four-and-a-half. In April 1915, he tried again, and, although nothing had changed, he was accepted. In his clear, strong handwriting, he wrote on the attestation paper that his next of kin was his mother, Alice, and that he had never previously served in the King’s army. He was a typical new recruit. He took the oath and was drafted to join the 5th Reinforcements for the 1st Battalion, which was in Egypt, on the verge of leaving for Gallipoli. Two months later, Bert departed from Sydney on the Ceramic.

After arriving in Egypt late in July, Bert soon became swept up in the excitement and drinking that accompanied going into Cairo on leave. He became infected with syphilis, and, before long, was out of the 1st Battalion and into Abbassia. Here he became acquainted — for the first time, but not the last — with Wassermann tests, injections of Arsenobenzol, and the daubing of mercury on his syphilitic lesions. When this treatment had little effect, he became another of the unlucky men chosen by Colonel Brady Nash to be sent back to Australia on the Wiltshire. It is apparent in hindsight that Bert’s troubles in Cairo in 1915 were caused by a very casual attitude to life; as we shall see, there would be many more boozy nights and bad decisions.

By the time of his being sent home, Bert’s brothers were also in the AIF. Reg enlisted about a week after Bert had, and placed in a reinforcement draft for the 1st Australian General Hospital in Cairo. Will enlisted a few months later, and was meant to be going to Gallipoli to join the 3rd Battalion. In October 1915, Reg departed from Sydney, followed a month later by Will. By the time his older brothers left Australia, Bert was already back, and in Langwarrin, and itching to get out.

After five weeks, he was discharged as fit for duty, with orders to go to Broadmeadows to join a new unit. However, somewhere between the isolation hospital to the south of Melbourne and the Broadmeadows camp to the north, he disappeared. Many men who left Langwarrin for Broadmeadows did not complete the trip: with pay restored, they seem to have become irretrievably distracted by the pleasures of Melbourne town in between. Very soon, Bert was posted as a deserter, and a warrant was issued.

About four months later, a short, wiry, blue-eyed young man presented himself at an AIF recruiting place in Melbourne and volunteered for enlistment. He said he was Michael Willis, aged 22 and working as a carter. From whom did Bert borrow this new identity? We know there were two men in the AIF called Michael Willis, but neither could ever have been in Bert’s proximity, and it is unlikely that he borrowed his new names from them.

In June 1915, the minimum height for AIF recruits was lowered to five feet two inches. At his enlistment as ‘Michael Willis’ in March 1916, Bert was found to be five feet three inches tall — even shorter than he had been a year earlier at Liverpool — so he could now be accepted without any fuss. In his same strong handwriting, he filled out a second attestation form, and once again declared he had never previously served in the King’s military forces and that everything he wrote was true. His attestation was duly sworn, witnessed, and certified by the recruiters, and he was accepted into the AIF for the 38th Battalion.

When Bert had originally attested, he had written that his mother, Alice, was his next of kin. For his attestation as ‘Michael Willis’, he nominated his sister Myra Pinson. We do not know if Myra knew at the time that he had done this, although she certainly knew later. We also do not know how Bert explained his re-appearance in Australia, or his need to re-enlist in the AIF using false names. Myra remained Bert’s next of kin for the rest of the war — although, as we shall see, his mother also became involved in dealing with the army on his behalf.

Albert Crozier in mid-1916 at the Broadmeadows camp. At the time, Bert was serving as ‘Michael Willis’, but he gave his correct name to the photographer. (AWM)

Following his successful re-enlistment, Bert was sent to Broadmeadows, where he belatedly completed the journey from Langwarrin that had begun four months before. From Broadmeadows, he was meant to go to Bendigo to join the 38th Battalion, which had just been formed there. However, an outbreak of meningitis in the Bendigo camp caused the unit to transfer to Melbourne, where it was reconstructed using fresh recruits, like ‘Michael Willis’. The battalion’s main body departed from Port Melbourne in June 1916, but Bert was in the 2nd Reinforcements, and did not leave until August, on the Orontes.

When the reinforcements arrived in England, they were sent, as usual, to a training camp; afterwards, they went to the Salisbury Plain and joined the 38th Battalion. In November 1916, when all preparations had been completed, the battalion left from Southampton for the port of Le Havre, in France. Soon they were living in billets at Strezeele near Armentieres, which was immediately behind the Western Front. Here they could hear the dull booming of artillery, and at night could see the glow from explosions illuminating the sky.

Bert’s casual attitude got him into much trouble. Even before arriving in England, he was punished at sea for ‘breaking ship’, which meant that, when the Orontes was in a foreign port, he had gone ashore without permission. Now in France, ‘Michael Willis’ received more punishments for absence without leave, including a very severe one by a court-martial.

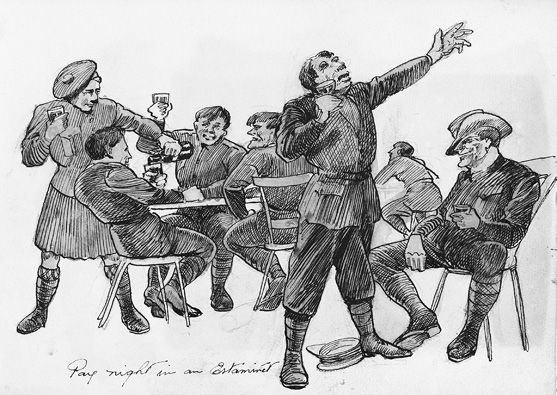

In France, Bert was exposed to the heavy-drinking culture of the AIF, and he evidently became very attracted to alcohol. Although army regulations existed to control drinking and drunkenness, they were inconsistently enforced by officers and NCOs, many of whom were drinkers themselves. The Western Front was awash with all kinds of booze, and estaminets and temporary bars followed the troops around. If men wanted to, just before battles, they could bolster their courage from big jars of British navy SRD rum.20 When they were away from the fighting, or on leave in London or Paris, binge-drinking sessions were a popular form of entertainment. A whole new AIF jocular language of drinking was invented to describe alcohol, drunkenness, and drinking situations.21 Later, diggers who survived brought this language, and their drinking and other addictions, home to Australia.

Smoking tobacco was also enormously popular with Australian soldiers, and English cigarettes — Woodbines, Senior Service, and Players — were supplied in their millions to the imperial forces. The epidemic of wartime smoking occurred long before the health risks were known: smoking was so normal, it was possible for brands to be given the seal of approval of King George V, and for Australian branches of the British Medical Association to start tobacco funds ‘for the comfort which our Australian boys at the front may derive from a smoke’.22

In June 1917, at Messines in Belgium, Bert received a severe gunshot wound when a bullet passed through the axillary fold where his arm joined the shoulder. This wound had several consequences for him. First, he was sent to England for long medical treatment at a hospital at Birmingham. His sister Myra Pinson, in Australia, the next of kin of ‘Michael Willis’, was duly informed by the army that this had happened. Second, while recuperating in England, Bert apparently forgot all about his nasty episode with syphilis in Egypt two years before. Evidently, he was also not bothering to use Blue Light kits: he was admitted to Bulford with syphilis and gonorrhoea. He told a doctor he had been infected by an ‘amateur’ prostitute in Edinburgh a month before, which meant that the infections were very advanced. He had to go through another long course of Wassermann tests and injections of Arsenobenzol and mercury for the syphilis, and urethral irrigations of silver for the gonorrhoea.

A third consequence of Bert’s wound was that, in June 1917, a week or so after the attack at Messines, a letter was sent to Myra by the 38th Battalion’s Church of England chaplain, the Reverend Captain Henry Hayden. The letter began, ‘You will have received the sad news of your brother’s death long before this note reaches you’, and went on to describe how ‘Private Michael Willis died like so many of his comrades a brave and gallant gentleman … a noble death for God, King and Country.’ Myra had been in constant contact with Bert, and so, although greatly perturbed when this letter reached her, she doubted her brother was dead. She wrote to army headquarters in Melbourne to question Chaplain Hayden’s letter, thereby provoking immediate corrective action. A ‘please explain’ memo was sent to AIF headquarters in London, and internal correspondence about this alarming error continued for months until early 1918, when the mistake was corrected. Eventually, an apology was sent to Myra; in it, the chaplain was blamed. In fact, it was not the chaplain’s fault at all, but that of the officer who had told him that ‘Michael Willis’ was dead rather than wounded.

All the attention drawn to ‘Michael Willis’ by Bert being wounded, and the killed-in-action mix-up as well, so worried the Croziers in Sydney that they decided to inform the authorities who he really was. Without revealing his period of service in 1915, Bert’s mother, Alice Crozier, wrote a letter to the army to say that her son

Albert Edward Crozier enlisted under the name Michael Willis and left Australia with the 38th Battalion … and was wounded last year … at Messines … and I would be very grateful if you would see he is placed on the records in his proper name it is at his request also there was no serious reason for him to do this for he was never in trouble in his life not before a police court and up to the time of enlisting never was away from home for one night. Just a silly streak he was young at the time.

The army replied by informing her that when ‘Michael Willis’ had enlisted, he had declared that his parents were dead. Alice was asked to make a statutory declaration averring that she was Albert’s mother. This was done, witnessed by a police magistrate, and sent with an accompanying note asking that Bert ‘not be penalised (my three only sons are doing their duty for their country abroad)’. Then began a long, slow process within the army bureaucracy to verify Mrs Crozier’s claim. Until that happened, Albert would need to keep serving as ‘Michael’.

While this was occurring in Australia, Bert was sent from England to rejoin his battalion in France in early 1918. Soon, he was in trouble again, punished for ‘leaving the ranks when ordered not to do so’. During the German spring offensive, the 38th Battalion fought a series of battles in the Somme Valley, and Bert was involved. Then, a few months later, he was wounded for a second time. The battalion was moving under enemy fire into trench lines at Vaire Wood when Bert was hit by a bullet in his right fore-arm. He was taken to an Australian hospital at Rouen, and, during his long stay there, the 38th Battalion advanced to the Hindenburg Line, far to the east.

When Bert rejoined the battalion, final preparations were underway for what was hoped would be the capture of a section of the Hindenburg Line along the Saint-Quentin Canal. The attack was launched at dawn at the end of September 1918, with the diggers advancing into an outlying maze of desperately defended German trenches. Bert was hit by a bullet again, this time deep in his right thigh. The wound was bad — the worst of the three he received — and he was taken straight to a field hospital, and then back to England to a hospital in Manchester. He had been shot during the last days of the 38th Battalion’s final attack of the war. By October 1918, the Hindenburg defences had been breached, and the German army had begun its final retreat. The following month, the war ended.

An entrance to a Saint-Quentin Canal tunnel, part of the Hindenburg Line of defences captured on 29 September 1918. (AWM)

Bert took opportunities during his convalescence in Manchester to ‘do a bunk’, and, on one occasion, was absent from the hospital for five days. Then, after he was sent to the AIF’s clearing hospital at Hurdcott, he was punished again, this time for ‘neglecting’ to obey orders and ‘neglecting’ to identify himself. Bert was also sent to AIF headquarters in London to sign a declaration that enabled his correct identity to be restored. In December 1918, now Albert Crozier once more, he was invalided home to Sydney because of the wound in his thigh.

Since 1916, the army had been investigating men who had returned to Australia in 1915 on the Wiltshire but had deserted after being sent from Langwarrin to Broadmeadows. One of these was Private Albert Crozier, whose whereabouts was unknown. The army was unaware of the connection between that soldier and Private ‘Michael Willis’ in France, and Mrs Crozier had not helped them make it. In early 1919, army headquarters in Melbourne finally connected the two, and their records were united and corrected. For reasons unknown, nothing was done about Bert’s desertion in 1915. In Sydney in April 1919, he was given a good discharge certificate: ‘medically unfit, disability — gunshot wound right leg’. This was written for his correct identity, and, later, he received the three imperial service medals, including the 1914–15 Star.

Bert’s older brothers, Will and Reg, had also fought in France, and were also repatriated in early 1919. In July 1916, Will had been captured at Fromelles, and he had spent the rest of the war as a POW in Germany. Reg had been twice wounded by shrapnel, and had been in hospital in England when the war ended. So, with all Crozier brothers safely in Sydney by Easter 1919, we can be sure there were hearty Crozier-family celebrations, and the women of the family, including Reg’s wife, Pearl, must have been relieved and proud to have their men back. The ugly scars of Bert’s three bullet wounds and Reg’s shrapnel wounds must have provoked interest and awe.

The family might have noticed, however, that Bert was now a heavy drinker, that drinking was an important part of his daily routine, and that there seemed to be no end to it. Perhaps they hoped that, after getting over the war and settling down, Bert’s drinking might stop. He could resume his good place in the footwear industry, find a nice young woman to marry, acquire a new home, or even a war-service farm, and start a family. Maybe he had a yearning, like so many other returned men of his age, for the respectable life of a family man. With enormous encouragement from their communities, and with uplifting inducements from the government, thousands upon thousands of ex-AIF men put the war behind them and followed that path.

During 1917, Ernest Dunbar made a number of drawings of Western Front drinking scenes. This one is Pay Night in an Estaminet, made with ink, pencil, and wash on paper. (AWM)

There were also thousands of other returned men for whom post-war life would not be so fulfilling. They were the fellows whose war experiences were so unnerving that they could never enjoy normal life again. They had survived the horrors, but now carried permanent reminders in their physical disfigurements and mental torments. Bert Crozier would never make the healthy adjustments needed to succeed as a civilian, nor find release from his addiction to alcohol. What seems to be evident is that Bert used alcohol to abate his pain, or perhaps pretended to himself that he was doing so. This might have been because of the ballistic traumas he still suffered from the gunshot wounds, or because of the long-term effects of the toxic treatments he had for VD, but none of that is clear.

Slowly but surely, he made the long descent to being unemployable and homeless, and stealing to get clothes to wear and money to live on. Within a decade of his discharge from the army, Bert was an outcast, living rough at the fringes of society, and sometimes in prison. He would never marry, and would never know the particular satisfaction that having a family could give. In the 1920s and 1930s, he drifted restlessly between the cities of Sydney and Melbourne, and the towns of Goulburn, Yass, Canberra, and Queanbeyan. He became a habitual petty criminal, and was frequently arrested and brought before magistrates in many cities and towns. To maintain a semblance of respectability in the police courts, he usually described himself as a ‘bootclicker’, but it had been years since Bert had clicked any leather uppers for shoes and boots.

Through the years of the Great Depression, he was arrested for stealing, drunkenness, abusive language, ‘loitering with intent to commit a felony’, and breaking and entering, and was often in prison. His police record was so depressing that he decided it was time for another identity change. Back in Sydney in 1936, he became ‘George Gordon’, and was then repeatedly arrested under that identity as well. As ‘George Gordon’, Bert was given three months’ imprisonment with hard labour for stealing from a department store. After his release, he stole a handbag from Woolworths and received six months, and then another six months for stealing pairs of socks. Bert was a regular at Parramatta Gaol, and also at the Concord Repatriation Hospital — not that it did him much good.

The magistrates who knew him, and had to make decisions about him, were sometimes surprised by his thinking ability. On one memorable occasion, he helped the Queanbeyan police court clarify a point of law, by pleading not guilty to a charge of drinking intoxicating liquor. At an earlier criminal hearing at the court, Bert had promised to refrain from liquor. Soon after, he had been found by police drinking methylated spirits at the showground in Yass. The ‘metho’ Bert was drinking was probably obtained from a hardware shop, and normally sold as a fuel. Because of its toxicity, it was not meant for human consumption, but was frequently drunk as a cheap alternative by people who could not afford to buy liquor, and by those who were banned from buying or drinking it.

In April 1939, Bert was brought before the Queanbeyan court to explain himself. He argued that he had not broken his promise, because methylated spirits was not intoxicating liquor. The two justices of the peace hearing the case consulted with the police prosecutor, and then made a surprising decision. They were unsure if methylated spirits was classed as intoxicating liquor under the Liquor Act, because it could be bought at shops that did not require a liquor licence for its sale. The bench found the charge disproved, and Bert was discharged. This victory for metho drinkers was broadcast to the world the following day by the newspapers in Sydney. But the following month, the incorrigible Bert was before the Queanbeyan court yet again, this time for drunkenness and using insulting words, and on three charges of stealing.

While he was locked up at Queanbeyan police station, a drifter mate called Michael Grady stopped by to see Bert — and stole a cheque from the police-station counter. Both Grady and Bert were taken to court, where Grady was charged with stealing the cheque, and both with having stolen a towel and a shirt from the Tourist Hotel. The police magistrate sentenced Grady to nine months’ imprisonment, and Bert to six months’. In sentencing Bert, the magistrate addressed him to say he was ‘evidently a man of intelligence, who could shape his life in the right direction if he so desired’.

In March 1940, this returned soldier was found on the main street in Newcastle, asking for money from passers-by. Bert was arrested, and a stipendiary magistrate sentenced him to 14 days of imprisonment with hard labour for ‘begging for alms’.

In 1939, Australia had entered the Second World War. Two years later, Bert decided to enlist in the Second AIF. From 1940, the age limit for AIF recruits had been raised to 40, but Bert was 47, so he would need to ‘make an adjustment’. In March 1941, at Paddington in Sydney, he presented himself to join up. For this new attestation, he provided the name of his widowed sister Elsie Leibick as his next of kin, and gave her address in Bondi as his own. Following his medical examination, when the bullet-wound scars in his shoulder, fore-arm, and calf were noted, he was classified as fit for military duties ‘Class 1 (Special)’. The ‘special’ annotation meant that Bert’s military service in the First World War was sympathetically recognised, and also that his age had been lowered to 45, the cut-off for ‘specials’. In reality, he was being recruited as a labourer, a kitchen orderly or some other low-skilled occupation needed at the time by the army.

In April 1941, Bert was drafted for service in the Northern Territory, and, while waiting in Sydney for this adventure to begin, he continued his relentless drinking. Two days after enlisting, he went absent without leave, and was fined; then he did it twice again, and was also punished for drunkenness. In May 1941, Bert was once more found drunk, and, at this point, the army decided he was an alcoholic. His enlistment only came to an end, however, when it was discovered that Bert had concealed his criminal past. It was for this reason that he was discharged. His third period of service in the Australian army had lasted just over two months.

Following his failed enlistment, Bert continued his restless wandering, drinking, and petty crime. In 1947, he was caught taking ten bottles of wine from a hotel; in a police court, he told the stipendiary magistrate that it was his 54th birthday, and that the wine was for ‘a bit of jollification’.

In the winter of 1953, he was back in Goulburn, where he stole a pair of pyjamas from a shop and was caught by police. In court again, he told the magistrate that he was drunk at the time; he was convicted of theft and fined £10. The following summer, when Bert was 60, he was in Goulburn again, and this time was arrested and charged with vagrancy. He pleaded guilty; a long list of his previous convictions was read, and he was sentenced to two months with hard labour.

By 1954, nearly all of Bert’s relatives were dead. His mother, Alice, had died in Sydney in 1939, and his brother Reg had died there in 1943. In 1950, Reg’s widow, Pearl, had died, and, that same year, Bert’s sister Elsie had died. In 1951, his unmarried brother Will passed away, and, in 1954, his brother-in-law Les Pinson also died. Now, the only ones left were Bert, the rootless alcoholic, and his respectable widowed sister Myra Pinson, who lived on the North Shore, and who had helped and protected him so much during his AIF years. Bert had outlasted almost all of his siblings, despite his hard life.

In August 1954, he was 61 and living in inner Sydney, and it was there that events conspired against him to bring his remarkable life to its sorry conclusion. At the time, he had been living for six weeks in a tenement house at 16 Albion Street in Surry Hills, a place where alcoholics and drifters found cheap rooms, not far from the trams and traffic in Elizabeth Street. In 1954, this suburb was a neglected slum of old warehouses, hotels, and dilapidated houses. There were many pubs in the area, including the old London Hotel on the corner of Albion and Elizabeth Streets, and no doubt Bert was known at many of them. By this time, his body had suffered about 40 years of heavy drinking, and it is very likely he had started losing his mind.

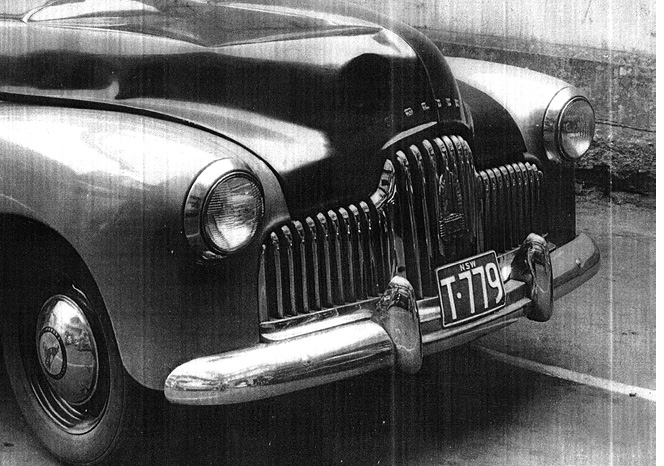

On the cool, clear night of Monday 16 August, just before nine o’clock, Bert, very drunk, was unsteadily making his way along the footpath outside the London Hotel. He was not far from his new home, but moving away from it — a small figure shuffling along in a shabby, brown army greatcoat. Further to the north, on Elizabeth Street, a Holden taxi driven by Roy Negus was slowly approaching. At the very moment that Negus passed the Albion Street corner, Bert suddenly veered onto the roadway, into the path of the cab. Later, Negus told police, ‘I don’t know where he came from. I did not see him till I had almost struck him.’ Negus slammed on the brakes and skidded to a halt, but too late. Bert was hit by the centre of the cab’s grille, and his head was slammed into the bonnet.

He was thrown by the impact onto the roadway, unconscious and terribly injured. The police arrived, an ambulance was called, and Bert was taken to Sydney Hospital, not far away, where resuscitation was attempted. It was noted by emergency staff that he smelt strongly of alcohol. Bert died at six o’clock the following morning. His unidentified body was taken to the city morgue, where it was inspected by a forensic examiner, who recorded that the cause of death was multiple serious fractures and lacerations.

A police photograph of the taxi driven by Roy Negus on the night of 16 August 1954. The buckling of the bonnet was made by the impact with Bert Crozier. (State Records Authority of NSW)

That morning, there was a problem identifying Bert. The police made inquiries in Albion Street, and their investigations led them to the shabby boarding house at number 16, where they spoke to the manager, Edwin Holland. That afternoon, Holland identified the body as Albert Edward Crozier, lately one of his tenants. Separately, the police had also taken the fingerprints of the dead man and, from Bert’s criminal records, were able to make a corroborating identification. A few days later, his remains were taken to the Rookwood Crematorium and, after the simplest of funeral services, cremated. By coincidence, the traffic collision that mortally wounded Bert in 1954 had happened just a few miles from where he had been raised 60 years before, in the Crozier home at Forest Lodge.

It was still not known why Bert had stepped into the path of the taxi, although it was thought that alcohol might have played a big part. After his death at the hospital, blood and urine samples were taken from his body and sent to the chemical laboratory of the department of health, and analysis showed that Bert had a very high concentration of alcohol. The following month, after two hearings at the Coroner’s Court, the coroner decided there was no evidence whatsoever of criminal negligence by the cab driver. The coroner found that Bert had been very drunk when he collided with the taxi, and that he had died from injuries accidentally received.

Of the many military and civil court proceedings involving Bert during the 40 or so years before 1954, the coroner’s hearing was the only one where he was not present to explain his actions. The evidence against him was that Bert Crozier was a drunk and a drifter, with a criminal record, and that he had, in effect, caused his own death. There was no one in court to explain how Bert had been seriously damaged by wounds and diseases in a terrible war, or that what he had done on Elizabeth Street was the end-stage of a long tragedy.