Chapter 5

The War on Hoodoo

Voodooism called plain racket by warring Tennessee Police.

–cover of Reading Times, 1937

A mid the racially charged climate of slavery and post-slavery Memphis, most displays of African culture invoked feelings of hatred, suspicion and fear throughout white communities. Rootwork and conjure were frequently equated with deviant behavior and criminality. Practitioners were forced into even deeper secrecy in order to preserve their traditional practices.

THE HOODOO MURDER

In 1868, a white woman from a prominent Memphis business family committed murder because of her belief in Hoodoo. It became a virtual hornets’ nest of controversy, as it raised issues of interracial relationships and African-based conjure.

Businesswoman Mary Grady and her husband lived in an area known as Grady’s Hill in South Memphis. Mary operated Grady’s Dance Hall, a popular dance house where many African Americans would come to relax, drink and dance. Mary’s husband worked during the evenings, and this left Mrs. Grady alone at home. Over a period of time, Mary developed a relationship with an African American taxi driver named Jim Rucker.

Rucker and Grady’s relationship began to be noticed by neighbors in the local community. It was considered extremely taboo for a white woman and a black man to be together, especially a well-known married woman. Soon, Jim Rucker stopped showing up at the Grady residence to meet Mary. Frustrated, Mary sought the services of an older African man who lived in the area considered to be a fetish worker or rootworker by locals. The man told Grady that her boyfriend had been “conjured” by an African American woman named Isabella Walton. The rootworker advised Mary Grady that this was very strong magic and that it could not easily be broken. The healer then advised that he would collect materials to create a counterspell to combat the spell that took Grady’s lover away.

The Memphis Daily Appeal explained, “Meanwhile while the fetish was gathering his herbs and grisgris, Mrs. Grady armed herself with a stout club, sought out the dark charmer who had cast such potent spells around her dusky paramour, and finding her, proceeded to administer the condign immediately.” Mary Grady decided to take the law into her own hands and that evening decided to pay Walton a visit. Armed with a Smith & Wesson pistol, Grady ambushed and shot Isabella Walton in the head. Walton sustained a serious injury but lived through the incident.

Following the perceived threat of predatory black Memphians and conjure, public fear of African-based folk practices grew to an all-time high as reports of child sacrifices and black magic permeated the media. The Memphis Daily Appeal carried this warning in July 1870: “If accounts in New Orleans papers be true, parents having pretty little children had better keep a sharp eye on them just about now. An exchange from that city says that this is the season of the horrible Fetish and Vandoo (Hoodo) rites, and that there is little doubt but that the stolen child, for which such thorough and prolonged search has been made was taken for sacrifice on the occasion of the great feast of Fetish.”

As early as 1869, there is a record of clashes between Memphis police and conjure culture. Officers with the Second District Police began a series of raids on the black settlement known as Rotten Row in downtown Memphis, arresting those African Americans who were out of work and confiscating and destroying Hoodoo-related tools such as mojo hands.

In 1873, Memphis police arrested Dennis Alexander on charges that he had harmed his son through the use of a folk treatment. The man’s son had been involved in a fight with a white man, whom he stabbed. The father sought out the services of a rootworker to help his son’s injuries. The rootworker prepared a medicine for the boy, and the father administered it to him. The son’s health began to get increasingly worse. Local critics of the incident in the local papers suggested that the father be sent to the penitentiary and that “those voodoo doctors and professors of the black art should be arrested and punished, they being the most guilty parties to the transaction.”

Many of the city’s “Negro Settlements,” as they were called, were under constant watch by police. The settlement, known as “Rotten Row,” was frequently raided, and several conjurers were arrested and their bags and roots confiscated by police. Courtesy of Memphis & Shelby County Room Photograph Collection.

Rootworkers and conjurers would find themselves forced into practicing in greater secrecy for fear of arrest. Some police departments in the South were reporting incidents such as “voodoo suicides.” Crime reports soon followed the activities of the Hoodoo culture on an almost daily basis:

Conjurers and rootworkers were caught in the crosshairs of an all-out war against Hoodoo in Memphis. The fear of African-based religious practices frightened many Memphians, as the fear of savage “Voodoo” rites created a social panic. Created by author using headlines from the Memphis Press-Scimitar, the Tennessean and the Memphis Appeal.

Arrest of a Negro “conjurer” tonight opened a police drive here against “voodoo doctors” who reportedly have been making large profits by selling “mystic potions,” guaranteed to accomplish practically anything desired by the buyer. Most of the buyers were gullible uneducated whites and Negroes of the poorest class. One of the chief claims made for the powders were that they would bring back wandering husbands, wives and sweethearts back to their loved ones. The voodooist call the potent potions various names such as “confusion dust,” “all-conquering powders” and “comeback powder” but police think they smell mighty like garden weeds, cinnamon, pepper, ammonia and such stuff.

Soon the aggressive arrests of rootworkers became less about crimes and more about a focused attempt to stamp out evidence of African culture. Years later, in 1937, Hoodoo would make the headlines again as a malevolent practice: “Unemotional police, classing the black magic of voodoo doctors as ‘just another racket’ moved today to stamp out the practice of the jungle art among superstitious negroes.”

Detective A.O. Clark with the Memphis Police Department had been called in to investigate the claims of a forty-three-year-old African American woman named Rosette Brown. Brown had paid a conjurer to bring her husband back to her. The conjurer gave the woman a powder that promised to contain the power to bring back her beloved. When the powder didn’t work, the woman called authorities. The detective scoffed not only at the idea of magical powder but also at the practice of Hoodoo: “These doctors are at work among the gullible Negroes. Their charms are bags filled with rocks or herbs of ground weeds mixed with spices. They find some woman whose husband has left her and convince her their ‘come back’ powders sprinkled about the house will make him return. They claim all sorts of magic powers but it’s just another racket. These Voodoo doctors don’t believe in their own magic.” While Africans and African Americans were being blamed for the Hoodoo market in Memphis, Brown reported that a white man had been the one who had brought the powder to Memphis from New Orleans.

UNLICENSED DOCTORS

A frequent charge against Hoodoo practitioners, particularly spiritual doctors, was that forms of medicine and healing treatments were being performed without proper licensure. In the 1930s, there was gossip among the Memphis Hoodoo community that in order to operate in the city some spiritual doctors must “grease the palm” of the correct authorities. Memphis spiritual reader Madam Myrtle Collins shared in Harry Middleton Hyatt’s Hoodoo Conjuration, Witchcraft and Rootwork, “They pay a shakedown. Yeah they charge yo’ bout $25 or $50, or whatevah they can beat aroun’ ’em. Every month or so they give em’ $50 or $60.”

For example, a Memphis-based herb company provided Raymond Godfrey, a conjurer from Nashville, with herbs used in healing rituals. Godfrey would perform rituals on clients and then prescribe various treatments for their ailments. During one spiritual consultation, Godfrey alleged that a client had snakes slithering around inside of his body. Godfrey prescribed a number of treatments along with amulets and rituals that were alleged to bring good luck and financial success to his clients. Nashville police raided Godfrey’s business and arrested the conjurer. A local judge fined him $100 and sentenced him to a local prison.

DOCTOR JACK

Early rootworkers in Memphis and throughout the state of Tennessee were prohibited from practicing medicine legally. However, the state legislature considered altering this law for a rootworker known around Tennessee as “Doctor Jack.” Doctor Jack was the practicing name of a slave by the name of Jack Macon. Born as a slave around 1783, Macon was owned by William H. Macon from Maury County, Tennessee. William Macon was the nephew of North Carolina senator Nathaniel Macon. Doctor Jack was allowed to travel and practice through many Tennessee counties, including Maury, Bedford, Giles, Hickman, Williamson and Lincoln.

Doctor Jack became known for his abilities to use roots and herbs to heal others. His services were available both to members of the black community and to whites. As Jack’s work as a healer became more popular, some local residents began to criticize his work. In 1843, locals in Fayette County began to protest the fact that Jack was allowed to freely roam and practice medicine wherever he wished. Complaints were filed with the Fayette County Circuit Court in the hopes of imposing fines on Jack’s owner.

A group of highly influential women in the white community decided to come to Jack’s rescue. In November 1843, a group of sixty-seven women petitioned the Tennessee legislature to modify a law that was being used to repress Doctor Jack’s ability to practice. Tennessee Act 1831 c. 103, S.3 prohibited slaves from practicing medicine. The women’s petition asked the state to repeal, amend or modify the act in order for Doctor Jack to be able to practice.

The petition’s abstract reads, “Sixty-seven ladies residing in Tennessee respectfully petition the Honorable Legislature of the State to repeal, amend or so modify the Act of 1831 c. 103. S.3 which prohibits slaves from practicing medicine as to exempt from its operation a slave named Jack the property of William H. Macon. They believe ‘Doctor Jack’ to be honest, honorable and skillful, especially in obstinate cases of long standing; and that the people ought not to be denied the privilege of commanding his services.”

The petition was accompanied by a number of testimonies regarding Doctor Jack and his ability to heal. The testimony of a Wade Barret from Giles County, Tennessee, regarding Doctor Jack’s ability to heal his sick wife speaks of Jack’s efficiency as a healer as opposed to conventional physicians in the region:

I do certify that my wife (Amelia) was taken unwell about the first of August 1829. She complained of great misery in the back and loins, together with a numbness in her thighs which threw her to bed the 19th of the same month. I immediately applied to a physician who formerly waited on my family from which she took medicine for about six weeks without receiving any benefits. I then applied to another, who I thought to be the best physician in the country, who attended on her about one month without the least apparent benefit, but she still grew worse and it was the opinion of the most of my neighbors that she must sink under her complaint if not speedily removed. In this case she was when about the first of December following I employed Doctor Jack (a colored man) belonging to William Macon of Maury County Tennessee, ten miles west of Columbia, who undertook her, he commenced with roots and to my great astonishment in a few days she began to amend and in a few weeks she was up and attending to her ordinary business of life and I believe she is as well at this time and enjoys as good health as she has done for several years.

A testimony submitted by an “L. Harwell” testified that Jack provided services for a fellow slave:

This is to certify that some time in the summer of 1829 that I had a negro man in a low lingering way and sunk under his complaint so rapidly that soon became entirely unfit for service, his disease seemed to threaten an immediate dissolution when I employed a Negro man called Doctor Jack belonging to W. Macon of Maury County Tennessee who commenced to doctor him with indigenous roots and to my surprise in a few weeks relieved him of all his complaints and in a few months I believe made a perfect cure. The negro is now well and fit for the hardest service given under my hand.

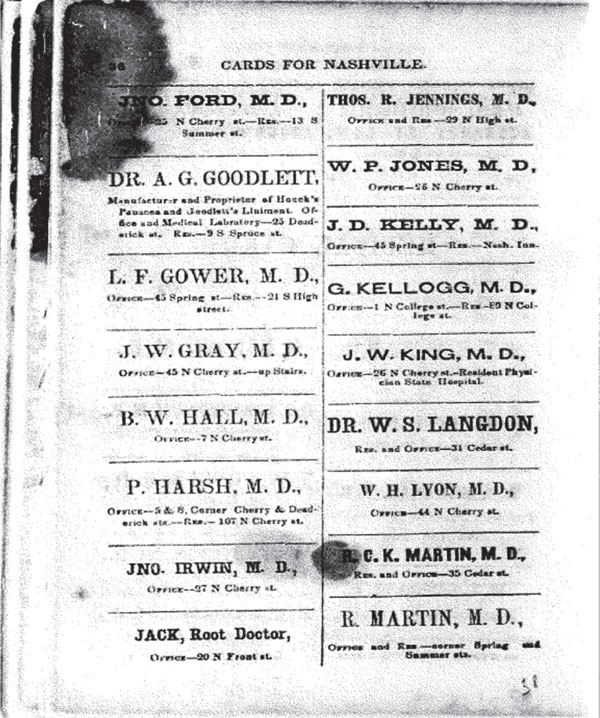

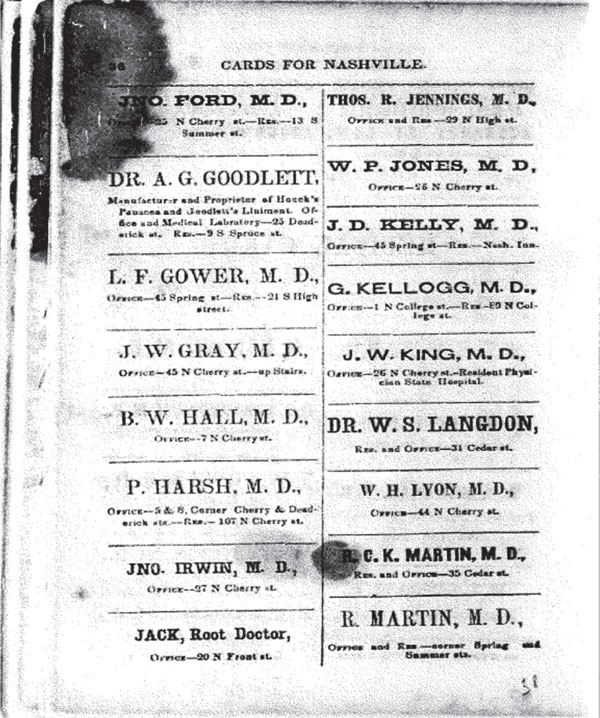

Loren Schweninger, in his excellent article “Doctor Jack: A Slave Physician on the Tennessee Frontier,” noted that in 1853, possible evidence pointing to Doctor Jack appeared in a Nashville business directory. An ad advertising the services of “Jack, Root Doctor,” located at 20 North Front Street in Nashville, Tennessee, possibly indicated not only the public acceptance of Jack’s work as a healer but also the possibility of Jack’s freedom from slavery.

Listing for “Doctor Jack,” an East Tennessee rootworker whose reputation brought African healing practices to the floor of the Tennessee legislature after several prominent women sought to seek an amendment allowing him to perform traditional healing among slaves and non-slave communities. Courtesy of Tennessee State Library and Archives.

FORTUNETELLING

One of the primary crimes that Hoodoo practitioners were commonly arrested for was fortunetelling. For Hoodoo doctors and spiritual readers, the practice of providing spiritual readings was considered “fortunetelling.” This was easy to prosecute, as there were state laws and local laws regarding charging fees for fortunetelling.

In 1956, a spiritual reader known as “Madam Glover” and a bishop of a Spiritual Church named William M. Watson were arrested by the Memphis Police Vice Squad on charges of fortunetelling. Watson claimed to be the leader and founder of the Universal Spiritual Unity Union of Christ-Like Spiritual Churches out of Forrest City, Arkansas. Officers sent two female undercover agents into the couple’s establishment to have a reading performed. The couple performed a spiritual reading and gave the agents information on how to terminate a pregnancy for a fee of three dollars.

Rootworkers and spiritual doctors could legally operate as businesses after the Tennessee Supreme Court ruled that spiritual readers and “fortunetellers” could legally purchase licenses to operate. Sister Ruby’s sister-in-law, Lilly Williams, known as “Sister Hope,” became the first spiritual reader to receive a license to operate in Shelby County. Courtesy of Memphis Press-Scimitar, University of Memphis Special Collections.

Many rootworkers and spiritual readers risked being arrested for providing spiritual services for clients. Memphis spiritual reader Ruby Stevenson, known as “Sister Ruby,” brought a lawsuit against Shelby County as a result of being denied a business license to operate as a spiritual reader. Courtesy of Memphis Press-Scimitar, University of Memphis Special Collections.

Glover and Watson were arrested, and agents discovered that they had been running a clever ruse involving the use of hidden microphones and speakers between rooms in which they could secretly share information about clients. Agents also found a collection of candles, incense and oils used by the couple in spiritual rituals.

Spiritual readers in Memphis could be charged with a misdemeanor charge punishable by fines of up to $500 and six months in jail. Some readers throughout the state had been allowed to pay a state “privilege” tax of $750 to operate. In October 1970, a Memphis-based clairvoyant named Ruby Steveson, known as “Sister Ruby,” approached the Shelby County court clerk to purchase a license to operate. The clerk advised her that according to local laws, she was not allowed to legally perform spiritual readings in Memphis. Steveson hired an attorney, who, in turn, filed a suit against the county and won.

Steveson’s sister-in-law, Lilly Williams, known as “Sister Hope,” purchased the first city and state license to practice fortunetelling in Memphis on October 9, 1970. This opened the doors for many Hoodoo-related readers to legally operate in Memphis and the Mid-South.

CONJURING CONS

While there were a number of false charges leveled against rootworkers and conjurers in the southern United States from outsiders, there were also a number of con artists who used the culture of Hoodoo to become financially lucrative. Memphis spiritual reader Myrtle Collins warned Harry Middleton Hyatt that there were more pretenders in the Hoodoo culture than real practitioners. One infamous con artist who went by the names “Doctor Johnson” and “Sam DeLeon” traveled throughout the southern United States, performing fake miracles and taking money from the gullible. Doctor Johnson was a white Hoodoo doctor who would go into African American communities offering goods and services related to Hoodoo. In Savannah, Georgia, the doctor would offer bags of herbs for fifty and seventy-five cents to the public. One particular customer recalled how Johnson made his “sell” of his herb product:

He made a number of hideous gyrations, walked around the room and standing in an erect position he lifted his right hand in the direction of the sky and commenced to revolve on his feet pointing with his index finger as he revolved North, South, East and West. He then rolled his eyes around looked out the door and said “Gimme me a piece of red flannel.” Fletcher produced the flannel and the doctor took from his pocket a small rule and measured on six inches of it. He then placed his hands in the shape of an arch over his head, allowed them to descend, and as they reached the red flannel he cut and measured another piece, but this time took only four inches. The negro was somewhat “awe stricken” at the strange spectacle and regarded the doctor as some sort of “semi-devil.” That was just what the doctor wanted. The doctor took two small pieces of hard substance having the appearance of dried herbs and wrapping them up in two pieces of red flannel, gave them to the negros. Johnson called it the “King of the World” and said that the substance enclosed was a “lodestone” but that it was “500 times stronger than anyone in the world.” Another remedy he called the “Queen of the World” and the two combined he said would exert a powerful influence over everything and effect marvelous cures.

The alleged Hoodoo doctor was stopped in his tracks in Savannah, Georgia. One of his clients went to the local court and swore out a warrant against Johnson for cheating and swindling. The client was so happy that he reportedly kissed the Bible twice for the judge as he swore that his testimony was true. Doctor Johnson went in front of the judge and admitted that he was originally from New York and tried to impress the judge with stories about his personal assets. He also opened a large cache of Hoodoo paraphernalia and, as the Tennessean newspaper reported, “took the magistrate’s breath away.”

Another Hoodoo con artist who traveled throughout the South was an individual named “Hoodoo John.” Hoodoo John showed up in Mobile, Alabama, around August 1866. Hoodoo John helped set up a con involving a young woman and her father around State Street in Mobile. The doctor and father began telling people in the community that the young woman had given birth to a number of live frogs and snakes. The men then charged curiosity-seekers fifty cents to see the reptiles in jars of alcohol. A local newspaper reporter visited the family, and the young woman claimed that the animals were placed inside her as a result of a mysterious powder she believes she had been given.

Many Hoodoo doctors within the state of Tennessee were charged with the offense of practicing fortunetelling or “swindling games.” Miles Thompson, a Hoodoo doctor in Nashville, was brought up on these charges when he was brought into court for making fake “hands.” The alleged conjurer had made hands from red flannel cloth and supposed magical materials. Clients alleged that the bags contained nothing more than coal dust and pills and string and provided no luck or success as promised.

One of the examples that many critics of Hoodoo used was an incident out of Chattanooga, Tennessee, involving a Hoodoo doctor named “Doctor Matthews.” Matthews was a Hoodoo specialist who frequently solicited paying customers. Matthews had found out that a local man had been sent to jail. He approached the man’s wife to talk about her husband. The slick conjurer promised that he could set her husband free for a nominal fee. The woman brought Matthews the amount he requested and was sent home with promises that he would be hard at work performing spiritual rites to free her husband. Once Matthews left the scene, he fled the city. Matthews’s trickery caught up with him, as authorities arrested him and sentenced him to three years in prison for defrauding the woman using Hoodoo.

Memphis was not exempt from Hoodooing con artists. Some con artists prescribed destructive acts in the name of Hoodoo. In 1943, West Memphis police arrested twenty-two-year-old Clarence Edwards on charges that he had lured a young boy into a wooded area, struck the boy over the head and cut his hand off. Edwards left the boy unconscious and bleeding. After Edwards returned home with the hand, he wrapped it in red cloth and placed it into his hip pocket. Police arrested Edwards and found the boy’s hand in the pocket of Edward’s zoot suit. Edwards explained to police that he had been instructed by a “voodoo doctor” on how to create a lucky charm using the boy’s hand.

Hoodoo and African folk practices would continue to be blamed for a number of crimes, incidents and natural catastrophes in the Mid-South. Some were rather comical. In 1934, Memphis city officials began to notice that the bank of the Mississippi River at Riverside was beginning to disappear. Large soil deposits were gradually growing smaller and smaller. City officials began an investigation into what could possibly be a potential natural disaster.

Memphis city police chief Will Lee reported to the public that more than a ton of clay had come up missing from the riverbank. An investigation into the missing clay revealed that a number of Memphians were eating the clay from the riverbank. Chief Lee shared, “They are loading it by the bucketful, digging it out with picks, knives and spoons.” Local physician Louis Leroy told the Commercial Appeal, “The negroes may have stumbled upon the practice by chance although it is probably part of an imported voodooism brought here from Puerto Rico or Africa where clay is much eaten by natives infested with hookworm.”

Clay wasn’t the only thing disappearing as a result of Hoodoo. In 1947, Memphian Erskin Johnson blamed the workings of Hoodoo for a domestic tragedy that had befallen him and his household. Johnson, a forty-twoyear-old railroad worker, told the court that the powers of Voodoo were being used to cause him to give his entire paycheck to his wife. Johnson claimed that his wife sought out the services of a Voodoo doctor to coerce him into giving up his hard-earned pay.

HOODOO AS A WEAPON

Hoodoo and African-based folk practices were constantly fighting an uphill war against presumptions about the practices. In some cases, accusations of Hoodoo and conjure were used as a means of slander. In a 1960 divorce case, the Shelby County Circuit Court watched as a husband and wife hurled accusations of candle burning, spellcasting and secret rituals against each other. Swing band musician Albert Jackson Sr. (father of Albert Jackson Jr., Stax legend and founding member of Booker T. and the M.G.’s) and his wife, Sarah Jackson, both testified that the other was trying to use a form of Voodoo. Albert testified that he had been coming home and finding candles burning in one of the couple’s closets. Upon inspection, he would find notes written on pieces of paper under the candles. Albert claimed that one of the messages was being used in an attempt to make him give up one of the family’s businesses, a locally operated service station. Another message, he claimed, was written as part of a spell to request that the couple’s son join the military. Lastly, a message was discovered that requested that Albert’s trumpet player go back to Philadelphia.

The bandleader introduced the tall candles and written messages to the court. Albert testified that his wife had taken a trip to New Orleans and claimed to have begun taking lessons in Voodoo. Jackson’s wife responded to the court, “It’s not true. If anyone is practicing voodoo it’s him.” She went on to testify that his mother was originally from Africa, and “he’s got a whole box full of herbs and heads she brought with her.” She went on to describe the heads, made from coconut, and claimed that he was using a small doll to place spells on her. After closing, the lawyers agreed that they were not making any headway with the Voodoo-related accusations and agreed on a property settlement.

As the demand for Hoodoo specialists grew in the Mojo City, so did the demand for Hoodoo-related products. Several prominent businessmen began to see the financial potential in manufacturing tools for conjurers. Memphis soon became home to some of the largest Hoodoo merchants in the country.