I

Always a Journey

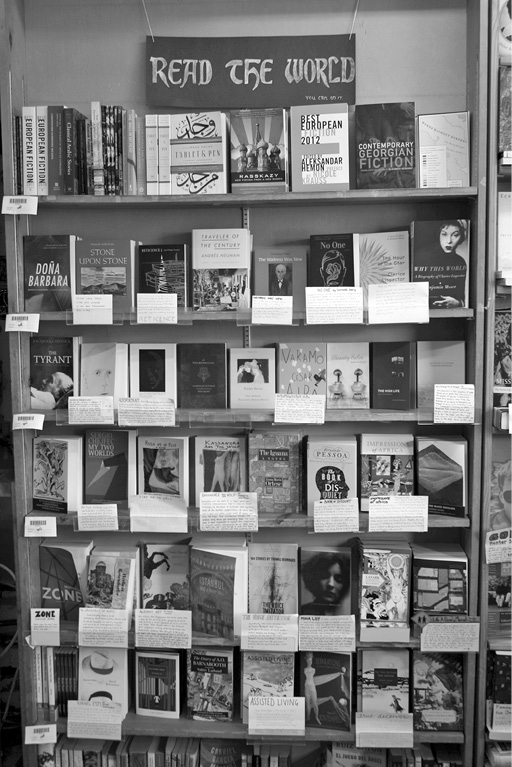

Every bookshop is a condensed version of the world. It is not a flight path, but rather the corridor between bookshelves that unites your country and its language with vast regions that speak other languages. It is not an international frontier you must cross but a footstep—a mere footstep—you must take to change topography, toponyms and time: a volume first published in 1976 sits next to one launched yesterday, which has just arrived; a monograph on prehistoric migrations cohabits with a study of the megalopolis in the twentieth-first century: the complete works of Camus precede those of Cervantes (it is in that unique, reduced space where the line by J.V. Foix rings truest: “The new excites and the old seduces”). It is not a main road, but rather a set of stairs, perhaps a threshold, maybe not even that: turn and it is what links one genre to another, a discipline or obsession to an often complementary opposite; Greek drama to great North American novels, microbiology to photography, Far Eastern history to bestsellers about the Far West, Hindu poetry to chronicles of the Indies, entomology to chaos theory.

You need no passport to gain entry to the cartography of a bookshop, to its representation of the world—of the many worlds we call world—that is so much like a map, that sphere of freedom where time slows down and tourism turns into another kind of reading. Nevertheless, in bookshops like Green Apple Books in San Francisco, in La Ballena Blanca (the White Whale) in the Venezuelan city of Mérida, in Robinson Crusoe 389 in Istanbul, in La Lupa (the Magnifying Glass) in Montevideo, in L’Écume des Pages (the Foam of Pages) in Paris, in the Book Lounge in Cape Town, in Eterna Cadencia in Buenos Aires, in La Rafael Alberti in Madrid, in Casa Tomada (House Taken Over) in Bogotá, in Metales Pesados (Heavy Metals) in Santiago de Chile, in Dante & Descartes in Naples, in John Sandoe Books in London, in Literanta in Palma de Mallorca—in all these places I felt that I was stamping some kind of document, accumulating stamps that attested to my journey along an international highway, the most important or significant, the best or oldest or most interesting or simply the nearest bookshop when it suddenly started raining in Bratislava, when I needed a computer connected to the Internet in Amman, when I was finally forced to sit down and rest for a few minutes in Rio de Janeiro or when I wearied of so many shrines in Peru and Japan.

I picked up my first stamp in La Librería del Pensativo (the Thinker’s Bookshop) in Guatemala City. I landed there at the end of July in 1998 when the country was still reeling from the outcry over Bishop Gerardi, who had been viciously murdered two days after he, the visible face of the bishopric’s Human Rights Office, had launched the four volumes of the report “Guatemala: Never Again,” which documented some 54,000 violations of basic human rights during almost thirty-six years of military dictatorship. They shattered his skull to the point that it was impossible to identify him by his facial features.

In those unstable months, when I switched abode four or five times, the cultural centre La Cúpula—comprising the gallery bar Los Girasoles (the Sunflowers), the bookshop and other shops—was most like home to me. La Librería del Pensativo sprang up in the nearby Antigua Guatemala in 1987 when the country was still at war, thanks to the tenacity of a feminist anthropologist, Ana María Cofiño, who had just returned from a long stay in Mexico. The familiar building on the calle del Arco had once been a petrol station and car-repair workshop. Distant shots fired by the guerrillas, army or paramilitary echoed around the volcanoes surrounding the city. As happened and happens in so many other bookshops, and to a lesser or greater extent in bookshops throughout the world, the importing of titles hitherto unavailable in that central American country, support for national literature, launches, art exhibitions, and all that energy that soon linked the place to other newly inaugurated spaces, transformed El Pensativo into a centre of resistance. And of openness. After founding a publishing house for Guatemalan literature, they also inaugurated a branch in the capital that remained open for twelve years until 2006. I was happy there—although nobody there knows that.

After it closed, Maurice Echevarría wrote: “Now, with the presence of Sophos, or the gradual growth of Artemis Edinter, we have forgotten how El Pensativo sustained our lucidity and intellectual alertness after so many brains had been devastated.”

I look for Sophos on the Internet: it is undoubtedly the place where I would spend my evenings if I still lived in Guatemala City. It is one of those spacious, well-lit bookshops with a restaurant and a family air that have proliferated everywhere: Ler Devagar in Lisbon, El Péndulo in Mexico City, McNally Jackson in New York, 10 Corso Como in Milan, or the London Review Bookshop in London, spaces that welcome communities of readers and soon transform themselves into meeting points. Artemis Edinter already existed in 1998, had done so for over thirty years, and now has eight branches; there must be a book in my library that I bought from one of them, but I do not remember which. In El Pensativo in La Cúpula I first saw the shock of hair, the face and hands of poet Humberto Ak’abal and learned by heart a poem he wrote about the ribbon the Mayans still use to tie up the bundles they carry on their heads that are sometimes three times their own weight and size (“For/us/Indians/the sky finishes/where el mecapal begins”); I watched a man crouch down to speak to his three-year-old son and saw the butt of a pistol sticking out from the belt of his jeans; I bought Que me maten si . . . by Rodrigo Rey Rosa, in a house edition, poor-quality paper I’d never touched before, which still reminds me of the paper my mother used to wrap my rolls in when I was a child, the feel of the thousand copies printed in the Ediciones Don Quijote printworks on December 28, 1996, almost a week after the democratic elections; I also bought there “Guatemala: Never Again,” the single-volume précis of the original report’s four volumes of death and hate: the militarisation of children, multiple rapes, technology at the service of violence, psychosexual control of soldiers, all that is contrary to what a bookshop stands for.

I found I had a mappa mundi rather than a passport the day I finally spread out all those stamps on my desk (visiting cards, postcards, notes, photographs, prints I had been putting in folders after each trip, anticipating the moment when I would begin this book). Or rather a map of my world. And consequently subject to my own life: how many of those bookshops must have closed their doors, changed address, multiplied, or must now be transnational or have reduced staff or opened a .com domain. A necessarily incomplete map criss-crossed by the length of my journeys, where huge areas remained unvisited and undocumented, where tens, hundreds of significant bookshops had yet to be noted (collected), though it nevertheless represents a possible overview of an ever-changing twilight scenario, of a phenomenon that was crying out to be analysed, written up as history, even if it would only be read by others who have also sat in bookshops here and thereabouts, so many embassies without a flag, time machines, caravanserai, pages of a document no state can ever issue. Because bookshops like El Pensativo have disappeared or are disappearing or have become a tourist attraction in countries across the world, have opened a website or been subsumed into a bookshop chain with the same name and then are inevitably transformed, adapting to the volatile—and intriguing—signs of the times. And here, before me, lay a collage that evoked what Didi-Huberman has described in Atlas. How to carry the world on your back, where—just as in the passageways of a bookshop—“the affective as much as the cognitive element” has equal value on my desktop between “classification and disorder” or, if you prefer, between “reason and imagination” because “tables act as operational fields to disassociate, disband, destroy,” and to “agglutinate, accumulate and set out” and, consequently, “they gather together heterogeneities, give shape to multiple relationships”: “where heterogeneous times and spaces continually meet, clash, cross or fuse.”

The history of bookshops is completely unlike the history of libraries. The former lack continuity and institutional support. As private entrepreneurial responses to a public need they enjoy a degree of freedom, but by the same token they are not studied, rarely appear in tourist guides and are never the subject of doctoral theses until time deals them a final blow and they enter the realm of myth. Myths like St Paul’s Churchyard, where—as I read in Anne Scott’s 18 Bookshops—the Parrot was one of thirty bookshops and its owner, William Apsley, was not only a bookseller but also one of Shakespeare’s publishers, or the rue de l’Odéon in Paris, which nurtured Adrienne Monnier’s La Maison des Amis des Livres and Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare and Company. Myths like Charing Cross Road, the intergalactic avenue, London’s bibliophile street par excellence, immortalized in the best non-fiction book I have read on bookshops, 84, Charing Cross Road by Helene Hanff (where, as in any shop selling books, bibliophile passion is shot through with human feelings, and drama coexists with comedy), a first edition of which I was excited to see on sale for £250 in the window of Goldsboro Books, an establishment that specializes in selling signed first editions, very close to the same Charing Cross Road where nobody could tell me where I might find Hanff’s bookshop. Myths like the bookshop dei Marini, later the Casella, that was founded in Naples in 1825 by Gennaro Casella and then inherited by his son Francesco, who at the turn of the twentieth century invited to his premises people like Filippo T. Marinetti, Eduardo de Filippo, Paul Valéry, Luigi Einaudi, George Bernard Shaw or Anatole France, who stayed in the Hotel Hassler del Chiatamone, but treated the bookshop as his front room. Myths like Moscow’s Writers’ Bookshop that in the 1900s and the early 1920s made the most of a brief interlude of revolutionary freedom and gave readers a centre of culture managed by intellectuals. The history of libraries can be told in minute detail, ordered by cities, regions and nations, respecting the frontiers that are sealed by international treaties and drawing on specialized bibliographies and individual library archives that fully document the development of stocks and cataloguing techniques and house minute-books, contracts, press cuttings, acquisition lists and other papers, the raw material for a chronicle backed by statistics, reports and timelines. The history of bookshops, on the other hand, can only be written after recourse to photograph and postcard albums, a situationist mapping, short-lived links between shops that have vanished and those that still exist, together with a range of literary fragments and essays.

When I was sorting out my visiting cards, leaflets, triptychs, postcards, catalogues, snapshots, notes and photocopies, I came across several bookshops that did not fit any geographical or chronological criteria, could not be explained in terms of the stopovers and paths I was tracing for others, however conceptual and transversal these might be. I am referring to bookshops that specialize in travel, a paradox in itself, because every bookshop is an invitation to travel, and itself represents a journey. But the latter are different. The word “specialize” points to their peculiarity. Like children’s bookshops, comic shops, antiquarian bookshops and those trading in rare books. Their specialist focus is evident in the way they categorize their books: not by genre, language or academic discipline, but by geographical area. This principle is taken to an extreme in Altaïr, whose main shop in Barcelona is one of the most absorbing bookish spaces I know. There they group poetry, fiction and essays according to country and continent, so you find them next to the relevant guidebooks and maps. Travel bookshops are the only ones where cartography outshines prose and poetry. If you follow the itinerary suggested by Altaïr, you pass by the window display to a noticeboard of messages posted by travellers. Behind that sits a collection of the shop’s house magazines. Then come novels, histories and themed guidebooks on the subject of Barcelona in a pattern followed by most of the world’s bookshops, as if the logic of necessity meant one must move from the immediate and local to what is most remote: the universe. Consequently, the world is next, also arranged according to criteria of distance: from Catalonia, Spain and Europe to the remaining continents, the world spreads across the two floors of the shop. Maps of the world are downstairs and beyond them, at the back, a travel agency. Noticeboard, magazines and all that reading matter can lead to only one outcome: setting out.

Ulyssus in Girona carries the secondary name of Travel Bookshop, and like the founders of Altaïr, Albert Padrol and Josep Bernadas, its owner, Josep María Iglesias, sees himself first and foremost as a traveller and secondly as a bookseller or publisher. Ulysses, the Paris bookshop, likewise has Catherine Domain at the helm. A writer and explorer, Domain obliges her staff to travel with her every summer to the casino in Hendaye. By symbolic extension, this kind of establishment is usually full of maps and globes of the earth: in Pied à Terre in Amsterdam, for example, there are dozens of globes that observe you on the sly as you hunt for guides and other reading matter. Its slogan could not be more insistent: “The traveller’s paradise.” Deviaje (Travelling), the Madrid bookshop, emphasizes its character as an agency: “Bespoke travel, bookshop, travel accessories.” The ordering does not alter the end product, because the truth is that travel bookshops throughout the world are also stores that sell practical travel items. Another Madrid shop, Desnivel (Uneven), specializing in exploration and mountaineering, sells GPS trackers and compasses. The same is true of Chatwins in Berlin, which devotes a good part of its display space to Moleskine notebooks, the mass-produced reincarnation of the artisan-made jotters that Bruce Chatwin used to buy in a Paris shop until the family in Tours that manufactured them stopped doing so in 1986. He relates this in The Songlines, a book published the following year.

Chatwin’s funeral was held in a West London church, though in 1989 his ashes were scattered by the side of a Byzantine chapel in Kardamyli, one of the seven cities Agamemnon offers Achilles in return for the renewal of his offensive against Troy in the southern Peloponnese, and near the home of one of his mentors, Patrick Leigh Fermor, a travel writer and, like him, member of the Restless Tradition. Thirty years earlier, a young man from the provinces by the name of Bruce Chatwin, without trade or income, had arrived in London to work as an apprentice at Sotheby’s, unaware of his future as a travel writer, a mythomaniac and, above all, a myth in himself. He was unaware, too, that he would give his name to a bookshop in Berlin. Two bookshops stand out among the many Chatwin might have discovered when he arrived in the city at the end of the 1950s: Foyles and Stanfords. One generalist and the other specializing in travel. One full of books and the other awash with maps.

In the middle of Charing Cross Road, Foyles’ fifty kilometres of shelves make up the world’s greatest print labyrinth. In that period it became a tourist attraction because of its size and the absurd ideas put into practice by its owner, Christina Foyle, who turned the place into a monstrous anachronism in the second half of the twentieth century. Ideas like refusing to use calculators, cash registers, telephones or any other technological advances to process sales and orders, or arranging books by publishing house and not by author or genre, or forcing her customers to stand in three separate queues to pay for their purchases, or sacking her employees for no good reason. Her chaotic management of Foyles—which was founded in 1903—lasted from 1945 to 1999. Her eccentricities can be explained genetically: William Foyle, her father, committed his very own lunacies before handing the shop over to his daughter. Conversely, Christina must be credited for the finest initiative taken by the bookshop in all its history: its renowned literary lunches. From October 21, 1930 to this day half a million readers have dined with more than a thousand authors, including T. S. Eliot, H. G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, Winston Churchill and John Lennon.

Such Notoriety now belongs to the past (and to books like this): in 2014 Foyles was transformed into a large modern bookshop and moved to the adjacent building at 107 Charing Cross Road. The reshaping of the old Central Saint Martin’s College of Art and Design was the responsibility of the architects of Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands, who met the challenge of designing the largest bookshop built in Britain in the twenty-first century. They created a large, empty central courtyard suffused with bright white light reinforced by huge lamps that punctuate the vast, diaphanous text, which is surrounded by stairs that go up and down like so many subordinate clauses. A cafeteria—which is always buzzing—is at the top, next to an exhibition room equipped for trans-media projects and the main presentation room. When you walk in you are greeted by a sign at ground level: “Welcome, book lover, you are among friends.” What would Christina see if she raised her head? She would see an entire wall commemorating her crowded lunches.

“Explore, describe, inspire” is Stanfords’ slogan, as I am reminded by the bookmark I keep as a souvenir of one of my visits to that shop. Although the business was founded in that same Charing Cross Road where Foyles still survives, its famous Covent Garden headquarters in Long Acre opened its doors to the public in 1901. By then, Stanfords had already forged a strong link with the Royal Geographical Society by virtue of producing the best maps in an era when the expansion of British colonialism and an increase in tourism had led to a massive rise in the printing of maps. Although you can also find guidebooks, travel literature and related items on the store’s three levels, whose floors are covered by a huge map (London, the Himalayas, the World), cartography plays the lead role. Even the bellicose variety: from the 1950s to the 1980s the basement was home to the maritime and military topography department. I remember I visited Stanfords because someone told me, or I read somewhere, that Chatwin bought his maps there, though there is no record of him ever having done so. The shop’s list of distinguished customers comprises everyone from Dr Livingstone and Captain Robert Scott to Bill Bryson or Sir Ranulph Fiennes, one of the last living explorers, to say nothing of Florence Nightingale, Cecil Rhodes, Wilfred Thesiger or Sherlock Holmes, who ordered the map of the mysterious moor that enabled him to solve his case in The Hound of the Baskervilles from Stanfords.

Foyles has five branches in London and one in Bristol. Stanfords has shops in Bristol and Manchester, as well as a small space in the Royal Geographical Society that only opens for events. Chatwin missed by a couple of years the opportunity to experience Daunt Books, a bookshop for travelling readers, whose first shop—an Edwardian building on Marylebone High Street naturally lit by huge plate-glass windows—opened in 1991. The store was a personal project of James Daunt, the son of diplomats, and thus used to moving house. After a stay in New York, Daunt decided he wanted to dedicate himself to his two passions in life: travel and books. Daunt Books is now a London chain with six branches. Au Vieux Campeur has sold maps, and travel books and guides as well as hiking, camping and climbing equipment from 1941 and now boasts a grand total of thirty-four establishments across France. Such is the way of Moleskine logic.

At the end of the nineteenth century and at the beginning of the twentieth, many amateur and professional artists took up the habit of travelling with sketchbooks that had thick enough paper to cope with watercolours or India ink and sturdy covers to protect drawings and paintings from the elements. They were manufactured in different parts of France and sold in Paris. We now know that Wilde, Van Gogh, Matisse, Hemingway and Picasso used them, but how many thousands of anonymous travellers did also? Where might their Moleskines be? Chatwin gives them that name in the Australian book we mentioned and it was what encouraged Nodo & Nodo, a small Milanese firm, to launch five thousand copies of these Moleskine notebooks onto the market in 1999. I remember experiencing, on seeing some of them or the limited editions following on from that first printing in a Feltrinelli bookshop in Florence, an immediate surge of fetishist pleasure, the kind that recognition brings. It is what any committed reader feels on walking into Lello in Oporto or City Lights in San Francisco. For years you were forced to travel to buy a Moleskine. It was not necessary to go to a Paris bookshop, though that did not mean you could find them in any bookshop in the world. In 2008 they were supplied to some 15,000 shops in over fifty countries. To cope with demand, production was moved to China, although the design remained Italian. Before 2009 I had to go to Lisbon if I wanted to visit Livraria Bertrand, the oldest bookshop in the world, which fleetingly opened a branch in Barcelona, the city where I live, and serial commercial expansion won yet another victory—its nth—over that old idea, now almost without a body to flesh it out: atmosphere.