As the Atom Bomb Said to the Peacenik

Throughout its five-season run, The Twilight Zone posited a number of possible end-of-the-world scenarios, but all had one thing in common. The sheer madness of nuclear war.

The fact that only one nation, the United States, had seen fit to deploy an atomic bomb against another nation was not seen as a crumb of comfort. Rather, it sometimes felt like the absolute opposite, as though karma alone guaranteed that one or more of America’s major cities would have to be vaporized to redress some vast cosmic balance. The fact that the very concept of karma was unknown to the majority of Americans at the time did not minimize those fears. People simply called it “fate.”

But the Soviets were not the only nation to have “the bomb”—by 1952, the United Kingdom had one as well, and by 1960, the French had become the world’s fourth nuclear power. Although those other nations had the wherewithal to launch a thermonuclear Third World War, only the U.S.S.R. possessed the incentive as well, and so the westernmost bulwarks of civilization geared itself to protect and survive.

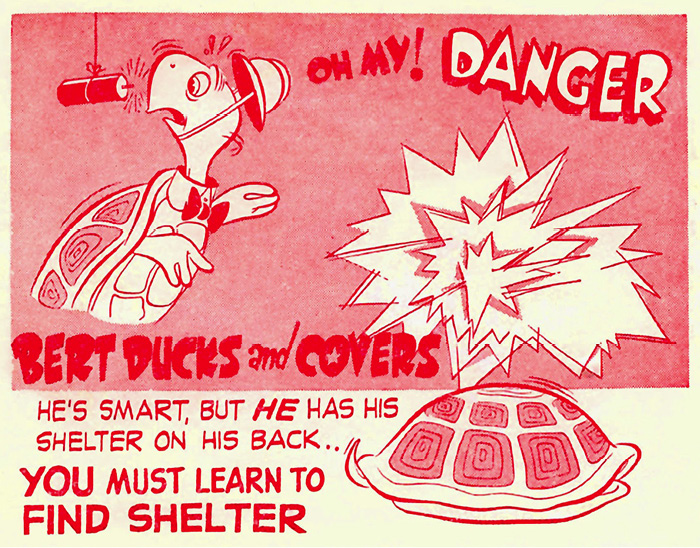

Bert the Turtle and Other Super Effective Ways to Live Through Armageddon

Today’s sophisticated society looks with almost undisguised glee, and incredulous disbelief, on the public information films of the 1950s, with their earnestly recounted advice on how to survive a nuclear attack—when, not even if, it came.

How cynical it all seems today. The government knew that the death toll would be in millions; that even the survivors would eventually wish they hadn’t lived through the initial searing blast. The bomb that fell on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, killed approximately eighty thousand people with the blast and its immediate effects. Less than six months later, injury and radiation had all but doubled that toll. Approximately 70 percent of the city’s buildings were destroyed outright; most of the remainder were damaged. Witnesses and survivors alike admitted that nobody, and nothing, had stood a chance.

And why was that?

Because they didn’t have Bert the Turtle to tell them what to do.

Bert the Turtle was the Civil Defense program’s spokesman of choice, and he was very aptly named. His name was Bert and he was a turtle. Meaning, when threatened, he popped his arms and legs inside his shell and waited out the emergency.

If you hear the siren, be like Bert. Stick your head in the sand and pretend you’re an ostrich.

Author's collection

So, what do we do when the siren sounds? We “duck and cover.”

When the bomb drops, the nicely reassuring voice-over told a nation, all you needed do was throw yourself to the ground, pull a sheet or a carpet over your head, and the blast would pass harmlessly over you.

Neither was that your only option. You could hide yourself under a table. You could paint yourself white (to reflect the blast) . . . there were, it seemed, so many ways to live through a potential nuclear holocaust that one wondered why anybody even made a fuss. Armed with a sheet and a pot of white paint, you had more chance of being killed in a road accident than you did when the Russkies dropped the bomb.

Or not. The government could issue all the reassurance in the world, but the majority of people remained terrified. Because . . . well, what happens if the bomb drops, and you don’t happen to have a carpet to hand?

You’re toast. And why are you toast? Because the Communists hate our freedoms.

(Hmmm. Does any of this sound familiar?)

Of course popular culture needed to comment on and reflect those fears, but how boring it would have been, for cinema audiences and actors alike, to simply churn out an endless succession of Communist invasion flicks. So it conjured up other invaders, barbarians and beasts and let them invade instead. Just so long as the American way of life was assaulted by the most hideous horror imaginable, before fighting back to wipe it out in not much more than an hour and a half.

All B-movie life is there. Giant spiders and killer cockroaches. Deranged doctors and sadistic scientists. An enemy agent truck driver inadvertently entrusted with transporting a cargo of unstable nuclear fuel through one major city or another. Hideous mutations brought on by man’s meddling. Vengeful legends awakening from eternal repose. And aliens! Humanoid or horrible, man-like or monstrous, it didn’t matter. Just so long as they held the end of the world in their hands . . .

The Twilight Zone was not the first television program to attempt to paint a more realistic, and certainly less allegorical, vision of life after the bomb. In 1954, an episode of CBS’s Motorola Television Hour, abruptly entitled “Atomic Attack,” adapted author Judith Merrill’s A Shadow on the Hearth in its depiction of a family attempting to flee after a bomb was detonated over New York City.

Three years later, in 1957, another CBS program, the documentary drama A Day Called X, focused on the real-life plans to evacuate Portland, Oregon, should an attack seem imminent. And two years later, again on CBS, The Twilight Zone presented “Time Enough at Last,” the first of its own miniseries of stories sent to batter Bert out of his reptilian complacency.

“Time Enough at Last” (First broadcast: November 20, 1959)

Rod Serling based his script on author Lynn Venable’s short story of the same name, first published in the January 1953 issue of the magazine If: Worlds of Science Fiction. Destined to receive a Directors Guild Award nomination, it was also the first to star actor Burgess Meredith, set to become something of a series regular.

“I am very grateful to Rod Serling,” Meredith told attendees at the Museum of Broadcasting’s Rod Serling tribute in 1984. “He provided me with several of the best scripts I ever had the luck to perform. In one case, the role of Mr. Bemis. There isn’t a fortnight goes by I don’t hear a compliment about it. Year after year, Rod used to have a part for me every season and every one of them [was] extraordinary.”

Bank clerk Henry Bemis, Serling’s opening narration informs us, is “a charter member in the fraternity of dreamers.” An avid reader, books are his sole defense against, and escape from, a world in which his wife, his boss, society itself, seem forever to be conspiring against him. Books are also the reason he is still alive. Taking his lunch in the bank vault, his nose buried in his reading, he is completely unaware of the bomb that explodes on the city streets above him; oblivious to the destruction of the world in which he lived. And, as one would expect, rather surprised when he returns to work after lunch to discover, there is no work to do. Just a smoking, dusty pile of rubble.

The last man on an empty world, the lone survivor of the hydrogen bomb, Bemis walks the devastated world alone. He is hungry, lonely, suicidal, dancing on the edge of utter despair. And then, salvation! A library stands, still intact amidst the ruins.

It is informative, here, to contemplate the cities that pock Rod Serling’s vision of the future. For we can take at least a crumb of comfort from the knowledge that, even in his most rancid of nightmares, this most prescient of pop cultural seers did not foresee the jungles of vainglorious monoliths, distended geometrics and improbable sex toys with which the architects of the twenty-first century have disfigured our once thriving cities.

No longer scraping the skies, today’s metropolises excoriate the very heavens, while LED displays brighter than a hundred suns or a thousand atom bombs sear our eyeballs with what has become the primal instinct of the modern caveman—not consumption but self-aggrandizement.

Serling’s cities remain functional, conventional, livable. Even in ruin, we discern their purpose; within the rubble, we still see home. Were today’s steel and glass carbuncles to be felled by nuclear holocaust, we would see only . . . steel and glass. It is frequently said that our cities are so brutally privatized today that nobody can even afford (or particularly want) to live there any longer. It is chilling to realize that, again, should the bomb drop, the wreckage would afford no more functional living space than the intact edifices do today, and isn’t that the ultimate triumph of corporate greed? The erecting of monuments that are no less fragile than the foundations of their owners’ own fortunes.

The city that totters, destroyed around Bemis, remains a city all the same. And the library promises him salvation of a sort, in the form of so many books that he could never read them all, no matter how long he might live. Which probably wouldn’t be long, but at least he won’t be bored while he waits for the radiation to devour him.

Except, as he makes his way to the building, he stumbles. His spectacles fall and break on the street. For the first time, amidst so much death, devastation and horror, Henry understands utter despair. “It’s not fair!” he cries. “It’s not fair.”

Poor Henry Bemis. Ever had one of those days when absolutely nothing seems to go right?

Officially licensed product. TM & © 2015 A CBS Company. THE TWILIGHT ZONE and TELEVISION CITY and related marks are trademarks of A CBS Company. All Rights Reserved. © JLA Direct, LLC. d/b/a Bif Bang Pow!

Well received though it was, “Time Enough at Last” did not pass completely unscathed. Again, throughout the 1950s, the American public was the not altogether unwitting recipient of a stream of public information movies, all aimed at providing it with what they needed to know to survive (or, at least, die very quickly in) a nuclear attack.

Most of them, as we have already mentioned, were so risibly simplistic as to defy modern-day belief. It was left to such latter-day movies as Peter Watkins’s War Game (1965) and the TV movie The Day After (1983), not to mention documentaries on the real-life strikes on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to ensure that nobody today remains in any doubt as to the deadly consequences of a nuclear war; while Raymond Briggs’s animated When the Wind Blows (1986) revealed even that era’s official reassurance as little more than diversionary claptrap.

But if late 1950s America was firmly in thrall to such absurdities, voices were at last beginning to speak out. In May 1960, the so-highly-respected Lithuanian American journalist and author Vilius Brazenas lashed angrily against the sheer absurdity of the nation’s preparations, the relentless distortion of even the vaguest facts, and the twisted interpretation of who would even drop the bomb.

Yes, the government was to blame for propagating so much nonsense in the first place. But so, condemned Brazenas, were “[the] atom horror shows and movies . . . [with which] we are being gradually scared into surrender, without being told or shown what that surrender would mean.” “Time Enough at Last” was among the culprits he called out by name.

“Why,” Brazenas implored, “couldn’t those brilliant scriptwriters and producers make a movie about American victims in Korea?”

Yet, for all the pathos that is ultimately heaped on Henry Bemis’s downcast shoulders, his plight has also raised more than a single smile. An episode of The Simpsons in 2003 focused on a mail carrier who accidentally breaks his glasses while delivering a copy of The Twilight Zone magazine.

An episode of The Drew Carey Show centers around its titular hero’s despair when, finding himself in a similar place to poor old Henry Bemis, he breaks his glasses as he contemplates a bomb shelter filled with back issues of Playboy.

And better than either of these, there’s that classic installment of Futurama where Bemis breaks his glasses, declares, “It’s not fair!” and then realizes his eyesight is perfectly fine.

Which is great until his eyeballs fall out.

No matter. He has all the time in the world. He teaches himself Braille, opens a book and his hands fall off as well.

Now that really isn’t fair.

“Two” (First broadcast: September 15, 1961)

Two years elapsed before The Twilight Zone returned to the theme of nuclear destruction, via the talents of a former carnival snake-oil salesman who graduated to screenwriting after his initial attempts to break into acting proved fruitless. Montgomery Pittman authored the season three curtain-raiser, a tale set amid the ruins of a city, shattered by war and peopled only by scavengers, the final survivors of the ultimate global cataclysm.

Society has crumbled; all that remains, as Serling’s opening monologue explains, is “a jungle, a monument built by nature honoring disuse, commemorating a few years of nature being left to its own devices.” Five years, in fact, but humanity struggles on.

The episode that introduced actress Elizabeth Montgomery as the third future star of Bewitched to appear in The Twilight Zone (following on from Agnes Moorehead and Dick York, her sitcom mother and husband), it features just two characters—Montgomery and Charles Bronson—and a single scenario, the ruined streets of a derelict city.

They meet while scavenging food—a tin of chicken legs that apparently remain tasty even after so many tears. So much for “Best by . . .” dates, then.

But they are not allies; that much is obvious from the different uniforms they wear and the different languages that they speak—he is American, of course, and she would appear to be Russian, at least judging from the single word (“překrásný,” or “very beautiful”) that she utters throughout the show’s duration.

The woman cannot understand a word her companion says, then, not even when he begins attempting to rationalize their plight by explaining how all of the reasons why they were fighting in the first place have been destroyed along with the city. All she sees is an enemy, a man who will kill her unless she kills him first.

Her attacks are unsuccessful—first he knocks her cold with a vicious right hook; later, she shoots but misses him. The fact that she even tried, however, brings home the futility of their plight to the man. Realizing there is no hope of ever persuading her to get past her hostility, he departs, leaving her to fend for herself in the future. And she, finding herself alone, finally comes to her own understanding. Their only hope of survival is to join forces.

She sets out in search of him, but first she removes her uniform, replacing it with a dress that he had scavenged from a broken store and handed her as a peace offering before the shooting started. He, too, is in civilian clothes, and we leave the pair walking side by side—an ending so simple, so straightforward, that Serling barely saw a reason to even deliver his traditional closing explanation. So he barely did: “This has been a love story, about two lonely people who found each other . . . in the Twilight Zone.”

Elizabeth Montgomery, bewitching the last man left alive, in the season 3 episode “Two.”

CBS/Photofest

“The Shelter” (First broadcast: September 29, 1961)

Another foreboding impression of the nuclear age, the Serling-scripted “The Shelter” was perhaps initially inspired by an NBC broadcast in which he participated earlier in the year, designed to promote the creation of a network of bomb shelters across the country.

In which case, his cynicism on the subject must have been very well camouflaged from the program’s makers.

The decision to broadcast this episode in late September 1961 was based around the growing national awareness of the United States’ Civil Defense requirements—indeed, just a week after “The Shelter” aired, on October 6, President Kennedy informed the nation, “In the event of an attack, the lives of those families which are not hit in a nuclear blast and fire can still be saved—if they can be warned to take shelter and if that shelter is available. We owe that kind of insurance to our families and to our country. . . . The time to start is now. In the coming months, I hope to let every citizen know what steps he can take without delay to protect his family in case of attack. I know you would not want to do less.”

Shortly after, Congress approved a $169 million budget to locate, mark and supply fallout shelters in existing public and private buildings. But still one hopes that the lessons of this episode, clumsily illustrated though they were, were taken on board by everybody involved.

The story is built around the belief that even the tightest-knit community will shatter and devour itself when its inhabitants’ personal safety is at stake. Certainly that is the case here, in a charming suburb in which everybody is close friends with everybody else . . . until the radio broadcasts the Three Minute Warning, the doomsday announcement that warns of an imminent nuclear strike.

But the people here will be safe, won’t they? Doctor Stockton, whose own birthday party was interrupted by the announcement, has a bomb shelter! Everybody piles around to his house, knowing that their dear friend will accommodate them within. But the doctor has bad news. His shelter is big enough for just three people: himself, his wife and their son.

Recalling the mob scenes that tore apart the facade of civilized society in the season one episode “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street,” the doctor’s neighbors explode with panic and fear, forcing their way into his home, battering at the doors of the shelter, tearing them down—not so that they might have a chance of surviving the imminent blast, but as if to ensure that the doctor and his family perish along with them.

But just as they succeed in breaking down the doors, the radio sparks back into life. The warning has been canceled. It was a false alarm.

So everybody apologizes and slinks sheepishly home.

“No moral . . . no message . . . no prophetic tract,” Serling’s closing words shrug. “Just a simple statement of fact. For civilization to survive . . . the human race has to remain civilized. Tonight’s very small exercise in logic . . . from the Twilight Zone.”

“One More Pallbearer” (First broadcast: January 12, 1962)

Barely three months on from “The Shelter,” another Serling original found itself mired in the ongoing rush to build fallout shelters. “One More Pallbearer” takes us into the world of wealthy industrialist Paul Radin as he builds a shelter with a difference. It’s not real. And neither will be the sound effects or television footage (filmed on an MGM set originally constructed as Munchkinland in The Wizard of Oz) that three very special people will be subjected to, when they come to visit him one day: Mrs. Langford, his old high school teacher, whom he still loathes because she caught him cheating, and both flunked and humiliated him as punishment; Colonel Hawthorne, the military commander who was responsible for Radin being court-martialed, stripped of rank and dishonorably discharged; and the Reverend Hughes, who once condemned Radin after his lust for money drove a young woman to suicide.

Radin’s scheme is very real, however. All three will be convinced that the end is nigh, and they will beg to use his shelter. He, magnanimously, will agree. But only once they have apologized for all the hurt they caused him when they revealed his true nature to a watching world.

Unfortunately, however, it doesn’t work like that. Though the broadcasts and warnings that he faked are all taken at horrified face value, his guests decline his offer of shelter. Faced with the choice between spending their last minutes on Earth with their families or being locked away below ground with the vile and loathsome Radin, all three bid him farewell and leave. Leaving him shattered by the failure of his plan and collapsing into insanity.

“The Old Man in the Cave” (First broadcast: November 8, 1963)

A highlight of The Twilight Zone’s fifth and final season, Rod Serling turned his attention to Henry Slesar’s “The Old Man,” a short story published in the 1962 issue of The Diners’ Club Magazine.

Set in that unimaginable but, in 1963, seemingly inevitable future that yawned in the aftermath of the Bomb, it pictured a world ten years on, by which time the majority of the people who survived the blasts have been wiped out by radiation, sickness or the simple battle for survival.

Once again, the ghost town that still houses one small enclave of people remains recognizable as a town. Buildings stand as they always have, worse for wear but still usable, live-in-able. The viewer extracts the same comfort from its familiarity as the inhabitants do from its durability.

Their leader alone seems distant—an old man who lives, as we have probably guessed from the title, in a cave, and whom nobody can claim ever to have seen, much less met. He is effectively a god. But even his divine sanctity is to be disturbed when the town receives a visit from a party of soldiers claiming to be representatives of the so-called Central States Committee.

The townspeople’s spokesman, Goldsmith, is not taken in by their story, but the newcomers’ leader, Major French, begins willfully countermanding the old man’s orders, trying to force a meeting with this mysteriously omnipotent being. But when he does so, it is to discover that the old man is, in fact, a computer.

Outraged, the townspeople riot against the machine, smashing it to pieces. They have already ignored one of the machine’s injunctions, that they refrain from eating a supply of food that it insisted was poisonous. Now they can go about the rest of their lives, free from its computerized orders.

Or not. The next morning, Goldsmith awakens to find the town strewn with the dead, victims of, indeed, a poisoned stash of food. . . .