World War II in The Twilight Zone

His initial intention was to simply drop out of high school and sign up on the spot. He was dissuaded from doing so by his civics teacher, however. Instead, he held on for graduation in 1943, then joined the U.S. Army the morning after the ceremony. He was assigned to the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 11th Airborne Division, and the following May, his division was shipped out to New Guinea.

Serling saw action for the first time in October, on the Philippine island of Leyte—the 11th Airborne Division deployed not, however, as the paratroopers they had trained to become, but as light infantry, clearing up any last pockets of Japanese resistance after the initial assault on the beaches.

Was he a good soldier? Not especially, say his various biographers, and it was telling indeed that much of Serling’s service was undertaken in the 511th’s demolition platoon . . . or “the Death Squad,” as it was nicknamed. Interviewed by Serling’s 1992 biographer Gordon F. Sander, the leader of the death squad, Sergeant Frank Lewis, explained, “He screwed up somewhere along the line. Apparently he got on someone’s nerves.”

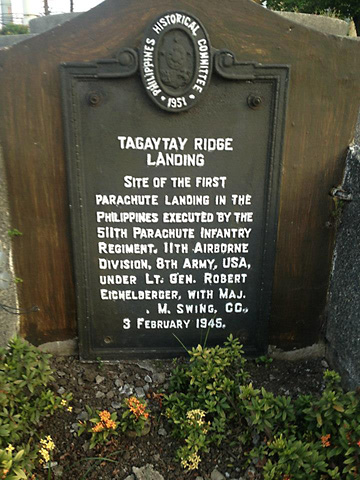

In February 1945, Serling and the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment landed on Tagaytay Ridge to join forces with the 188th Glider Infantry Regiment and march on the Philippine capital, Manila.

There followed one of the bloodiest urban conflicts of the Pacific war, as some seventeen thousand Japanese defenders under Vice Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi honeycombed the city with booby traps, land mines, grenades and gunfire, and prepared to fight to the death.

It would be over a month before the United States could describe the city as liberated, with Serling’s regiment at the forefront of the battle. But at a terrible cost. Over four hundred of Serling’s fellows were killed as the 511th experienced a 50 percent casualty rate—Serling himself was seriously injured (and three of his comrades died) when a Japanese antiaircraft gun turned its firepower against mere, unprotected human flesh.

He survived the campaign, but he was not unscathed. Physically wounded twice, Serling was to bear the emotional scars for the remainder of his life; indeed, many commentators have since pinpointed Leyte and Manila as the crucial events in Serling’s development as a writer—and, perhaps, even its genesis.

Serling himself later acknowledged that the Philippines became a recurrent setting for his stories, and not even a return visit to the islands in the early 1960s could erase the horror. What, he asked in a letter to a friend when he returned, could he say about the trip? Nothing good, it seemed. Nothing had been purged, nothing laid to rest. Instead, all wounds came screaming back to the surface, to be re-examined once again in the hope that age and experience might make some sense of them.

Even more influential than the fighting, however, was his wearing familiarity with death—not as the end product of some painstakingly created horror tale, but as a random, pointless and often thrill-less snuffing out of life.

On one occasion, Serling and his fellow death squad members were relaxing beneath a palm tree, listening and laughing as one of their number, Private Melvin Levy, launched into one of the hilarious comic monologues for which he was renowned.

Overhead, they heard the drone of a U.S. aircraft preparing for one of the food drops that kept the ground troops supplied, vast crates of food and equipment that sailed down from the heavens—and, on this occasion, landed on Private Levy, decapitating him in mid-sentence. And, contrary to everything Lights Out had ever suggested in the past, the accompanying sound effect was nothing like a cabbage being chopped in half with a meat cleaver.

The marker that today marks the site of one of the Pacific War’s most ferocious conflicts.

Ryomaandres/CC BY-SA 3.0/Wikimedia Commons

“Judgment Night” (First broadcast: December 4, 1959)

Just three months into the premier season of The Twilight Zone, Serling returned to World War II for a fast-paced nautical chiller that could easily have been based on the terrors that accompanied any of the many vessels that attempted to cross the Atlantic Ocean during those terrible years.

The seas were alive with German U-boats, stealthy submarines that hunted in packs like wolves, but were each capable of single-handedly tearing a passing vessel apart with their payload of high-explosive torpedoes. No wonder Carl Lanser, a passenger aboard the S.S. Queen of Glasgow, is scared out of his wits.

Yet it is not only the immediate future he fears, as his mind fills with visions of the ship being destroyed. He suffers, too, from déjà vu, the inescapable sensation that he has taken this journey before. And he knows how it is destined to end.

How? Because, even as the shipboard Lanser tries desperately to warn the captain and crew that he had a premonition that something dreadful was about to occur . . . that it would occur, at 1:15 in the morning . . . scant yards away aboard a German U-boat, Kriegsmarine Kapitan Carl Lanser is giving the order for the torpedoes to be fired. The S.S. Queen of Glasgow will be destroyed, and the captain can only hope that God will forgive him for killing so many women and children. But he doubts such mercy will be forthcoming. Rather, he fully expects that, henceforth, he is damned, and destined to die the same death as the victims of his attack.

Because, as Rod Serling’s closing words declared, “This is judgment night in the Twilight Zone.”

One of Germany’s most feared wartime weapons—U-Boats preparing for “Judgement Night”

Everett Historical/Shutterstock.com

“The Purple Testament” (First broadcast: February 12, 1960)

Two months on from “Judgment Night,” Serling journeyed back to his own years of military service, to depict a U.S. Army infantry platoon, in action on the Philippine Islands during the last months of the war, in 1945.

The camera scans the young warriors. These, Serling intoned, “are the faces of the . . . men who fight, as if some omniscient painter had mixed a tube of oils that were at one time earth brown, dust gray, blood red, beard black and fear yellow-white. And these men were the models. For this is the province of combat, and these are the faces of war.”

Taking its title from a line in Shakespeare’s Richard II (and not Richard III, as Serling’s closing narrative stated), one of The Twilight Zone’s hardest-hitting episodes of all focuses on Lieutenant Fitzgerald as he wrestles with the recent deaths of four men in his platoon—not because the deaths themselves could have been prevented, but because some bizarre sixth sense had warned him in advance the four would perish. And Captain Riker (played with astonishing grit by Dick York), the man on whom he unburdened himself, will be next. It is written in his face.

Of course, what Fitzgerald says is impossible; no man, Captain Riker believes, had that power of precognition. No, the general feeling around the camp is that the strain of the conflict has finally taken its toll on poor Fitzgerald’s mind.

Even when Riker fails to return from a mission, mowed down by enemy sniper fire, HQ continues convinced that Fitzgerald is simply cracking up. And he might even have believed that himself, had he not caught a glimpse of his own reflection in the rearview mirror of the jeep that is taking him to the hospital. Drawn across his face, and that of his driver as well, is the same dread portent. Just minutes later, the jeep strikes a land mine. Both of its occupants are killed.

Dean Stockwell was originally considered for the role of Fitzgerald; he turned it down, and William Reynolds was recommended instead, apparently by director Dick Bare, with whom he was working on the MGM series The Islanders. He enjoyed the shoot, too, later recalling a side of Rod Serling that, perhaps, is too often overlooked: the dedication that saw him attend every filming he could, and his willingness to fool around when the time was right.

One of the manifold myths that today surround The Twilight Zone revolved around Reynolds and director Bare. With “The Purple Testament” complete, the pair moved on to Jamaica, shooting background for The Islanders before returning to the United States on the very same day that their episode of The Twilight Zone was to be broadcast. They were traveling aboard a Grumman Goose seaplane, when suddenly engine trouble saw the plane go into an uncontrollable dive into the sea.

Back in Hollywood, news of the crash arrived hours before there was news of any survivors, and the story goes that the episode was immediately pulled from the schedule. Very little, after all, could be in worse taste than airing a show in which an actor has a premonition of his own death, on the same day that he did in fact die.

In the event, both men survived, albeit seriously injured (there was also one fatality), and the episode was never, in fact, in danger of being culled.

It made for a terrific story, though.

“King Nine Will Not Return” (First broadcast: September 30, 1960)

Serling and The Twilight Zone returned to World War II early in season two, but this time it was to the North African front in 1943. There, amid the unforgiving desert sands, a North American B-25 Mitchell bomber of the 12th Air Force, code-named King Nine, choked out her final breaths, shot down as she flew from Tunisia on a bombing mission over southern Italy. She did not even suffer a direct hit, just an errant piece of flak from the antiaircraft batteries, gashing a great hole in one of her wing tanks. And now Captain James Embry awakens to find himself alone in the wreckage of his aircraft.

There is no sign of his crew, and no sound from his radio. His only companions are hallucinations, the ghosts of his missing companions and, roaring through the sky above him, jet aircraft such as he has never seen before.

He screamed—and awakens again, a patient in a modern-day hospital, to which he had been committed after reading a newspaper article that caused his mind to snap. Years before, he should have been on board a bomber that crashed in the desert . . . should have been, but wasn’t. Now the wreckage of that bomber has been found, reawakening the guilt that has lain dormant in his mind for the past seventeen years.

So how does that explain, as his doctor and a psychiatrist leave the room, the trickle of desert sand that they see falling out of the sick man’s shoe? “The question,” says Serling’s closing monologue, “is on file in the silent desert. And the answer? The answer is waiting for us in the Twilight Zone.”

The inspiration behind this tale was laid bare by the story line—the real-life discovery of a crashed B-24 Liberator, the Lady Be Good, in the Sahara Desert. No bodies were found, no parachutes were aboard. Her crew, listed as missing in action since that fateful day in April 1943, remained so classified.

Variety, always a strong supporter of The Twilight Zone throughout its first season, seemed initially to have leaped aboard its return with glee, discussing the premise and inspiration for the story with considerable enthusiasm. But then the knife was twisted. “It was an acting tour-de-force for Bob Cummings, but neither his superlative one-man performance nor the script was equal to holding audience attention for some twenty minutes when it at last was revealed the captain was a patient in a mental ward. . . . The quick windup, after the moody, suspenseful beginning, was a letdown. It gave the impression that Serling had suddenly run out of ideas.”

“Deaths-Head Revisited” (First broadcast: November 10, 1961)

The first weeks of season three saw Serling return once again to his World War II–time fascinations—which, it is always worth remembering, were rooted in a past that was scarcely more distant in 1961 than the events of 9/11 are from today.

This time, however, his subject matter might not perhaps be deemed a suitable topic for “entertainment,” no matter how earnest the underlying morality.

As the episode aired, the international media was utterly transfixed by what many were calling the Trial of the Century . . . yes, we might cynically nod, one of the many to have had that lofty title bestowed upon them. This time, however, the facts lived up to the hyperbole, for it was the long-awaited trial of one of the most notorious Nazi war criminals of them all, Adolf Eichmann—the former head of the Gestapo office for Jewish Affairs and the organizer of the transport systems that conveyed his victims to the death camps.

The previous year, in May 1960, Israeli Mossad agents tracked and then snatched Eichmann from his home in Argentina, where he’d been living as a fugitive since the war’s end; and on April 11, 1961, his trial began in Jerusalem. Eichmann was charged with fifteen counts of crimes against the Jewish people, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and membership in a hostile organization, at a trial that was telecast around the world.

In fact, Serling later revealed that he wrote his script no more than two weeks after the trial’s initial broadcast in the United States, with broadcast scheduled just as the trial approached its climax, in the continued glare of the world’s cameras. Indeed, barely six weeks later, on December 15, 1961, with Eichmann found guilty of all the charges, he was sentenced to death. “Deaths-Head Revisited” (the title a play on author Evelyn Waugh’s classic Brideshead Revisited) could scarcely have been more aptly timed.

Yet the reawakening of so many appalling memories was very much part and parcel of American television programming at the time. Casablanca, Combat Sergeant, O.S.S. . . . with World War II still so fresh in the collective memory, all championed the war against the Nazis, a campaign that only escalated as the 1960s progressed. Indeed, as late as 1990, and the reunification of the West and East German nations that the end of the war had divided, Saturday Night Live’s Dennis Miller was still able to get a laugh and a major nod of agreement when he compared the event to “Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis getting back together. I haven’t really enjoyed any of their previous collaborations, and I’m not sure I need to see their new stuff.”

A quarter of a century on from that, and with the reconstituted Germany so clearly the economic and political top dog in a united Europe, the joke is less topical and, perhaps, less acceptable. But in 1961, just one look at Herr Schmidt, newly arrived in a pretty Bavarian village eight miles northwest of Munich, was sufficient to chill the bones of many viewers.

He has come, he has no problem admitting, to visit the ruins of Dachau, the wartime concentration camp that stood on the outskirts of the village. For there, some seventeen years earlier, he had served his genocidal masters, only the name by which they knew him was not the nondescript Herr Schmidt.

Back then, he was an S.S. captain named Gunther Lutze, and Rod Serling’s narration fills in the blanks. “He was a black-uniformed, strutting animal whose function in life was to give pain. And, like his colleagues of the time, he shared the one affliction most common amongst that breed known as Nazis . . . he walked the Earth without a heart.”

Death camp tourism may or may not have been a pursuit enjoyed by many former (but still unrepentant) Nazis, but Herr Schmidt is one of those for whom the walls, fences and horrors of the concentration camps will never lose their charm.

The first of the Nazi concentration camps to be opened, just weeks after Hitler assumed power in March 1933, Konzentrationslager-Gedenkstätte Dachau was originally intended for political prisoners. As the regime’s list of enemies increased, however, so the camp population swelled to include criminals, foreign nationals, Jews, gypsies, minorities and more. It is, perhaps, Schmidt’s bad luck that one of their number, a man named Becker, has chosen to revisit the camp on the very same day as he.

The years have not changed Schmidt’s appearance. Becker instantly recognizes the older man, and warns him, too, that justice awaits in the form of a tribunal made up of the ghosts that still haunt the camp. And so it does, and even as the indictments are read, Schmidt not only hears the words, he also feels the tortures that he once distributed so freely. And when we next see the despicable old Nazi, he is in a hospital, his mind shattered by the horrors that the spectral court visited on him.

Shocked by the state of his patient, but with no awareness of what sent the man hurtling into insanity, the doctor can only ask how and why the camp is even permitted to stand any longer. But Serling’s monologue answers that question. They must remain standing, so that they are never forgotten.

Still chilling decades later, the death camp at Dachau, setting for the episode “Death’s Head Revisited.”

Avantgarde Design/Shutterstock.com

“A Quality of Mercy” (First broadcast: December 29, 1961)

The final Twilight Zone of 1961 was another Rod Serling script, this time based on a story idea by Sam Rolfe—creator of Have Gun—Will Travel and an integral part of the team that developed The Man from U.N.C.L.E., when he stepped in to replace Ian Fleming as creative advisor and came up with the U.N.C.L.E. acronym (United Network Command for Law and Enforcement) itself.

Rolfe was, in fact, set to write the teleplay himself, only for other obligations to force him to back out. But the story’s setting in the Philippines in August 1945, during the last weeks of World War II, unquestionably establishes the tale deep within the realms of Serling’s own creativity, with his opening monologue reflecting with all-too-much realism the sheer exhaustion of the time.

We join Sergeant Causarano and his weary men in Corregidor in the midst of a deadly standoff, confronted with an equally exhausted, wounded group of Japanese soldiers, sheltering in a cave that the Americans’ weaponry cannot penetrate.

The only solution, it seems, is that demanded by the newly arrived Lieutenant Katell—namely, a head-on assault against the cave. But before he can send his shattered, and unwilling, troops into action, time slips to one side and suddenly Katell finds himself on the other side, a Japanese lieutenant at the battle of Corregidor, three years earlier. And now it is he who is being ordered into action by a bloodthirsty commander, to take out a group of wounded Americans, trapped in a cave of their own.

Katell pleads with Captain Nakagawa, begs him to show mercy to the enemy, but of course the older man won’t listen. The devils must die, no matter how badly injured the men might be.

Then time slips again, and Katell is learning that the atomic bomb has just been detonated over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. He is ordered to fall back and take no further action until the Japanese response has been gauged. With luck, the war will be over in days. And Katell, his earlier bloodlust quenched by his most peculiar experience, agrees.

It’s a clumsy story, despite a magnificent performance from Dean Stockwell, and despite, too, being drawn at least in part from one of Serling’s own experiences. His father passed away while Serling was on active duty, and he requested emergency leave to return home. It was refused; compassion had no place in the U.S. military in wartime.

“The Encounter” (First broadcast: May 1, 1964)

Born in 1913, and best known as the author of the novel Detour (1939), Martin M. Goldsmith was already an established screenplay writer when he offered up “The Encounter” to the final season of The Twilight Zone—a war story that takes place far from the battlefields, both geographically and chronologically. Rather, it is set in suburbia, where Mr. Fenton, a veteran of the Pacific War, hires Arthur Takamuri, a Japanese American gardener, to help him clear out the attic.

There, among the accumulated detritus of a lifetime, Fenton comes across a Samurai sword, picked up during the war as a souvenir, but as he hands it over to Arthur to look at, a strange, and violent change comes over the older man.

Recollecting the war in ever darker and deeper detail, he suddenly attacks his helper. Arthur fights back, blocking the old man’s blows with the sword, but as quickly as the attack began, it ends. Fenton returns to normal, and the two agree that the heat of the attic, and the beers they’ve been drinking, must have gone to their head.

They decide to go downstairs, but discover that the door is jammed, and now it is Arthur who is beset by visions, remembering how his father was one of the men who signaled the Japanese aircraft that attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and ignited the Pacific War in the first place.

More arguments, more struggling. Fenton becomes suicidal, insisting that the war will never be over until Arthur stabs him with the sword. Arthur resists, but the vicious blade ends up piercing Fenton’s body regardless, killing him. And Arthur, drawing the sword from the corpse, leaps out of the window with a cry of “banzai,” even as the jammed attic door creaks open.

It was a strange tale, and one guaranteed to arouse considerable comment, provoking so many accusations of racism that CBS would never repeat it. Not until the 1980s brought The Twilight Zone to home video could it again be viewed.

Fittingly, perhaps, “The Encounter” was The Twilight Zone’s final trip back to the war; its message a jarring reminder that the conflict did indeed not end just because the politicians had signed a piece of paper. Serling’s daughter Anne told USA Today in 2013, “I vividly recall . . . my dad having nightmares [about the war], and in the morning I would ask him what happened, and he would say he dreamed the Japanese were coming at him. So it was always present. . . .”