17

Cheating Death, Racing the Devil . . .

And Other Fortuitous Adventures

Of course, humans (or even aliens) are not the sole cause of anguish in this world. The Devil, the personification of evil and wrongdoing too, can take some credit for a lot of society’s misdeeds and missteps—or at least he can if the twilight zone has any say in the matter.

Rod Serling’s personal religious beliefs had very little impact on his writing. He was keenly aware, however, that other peoples’ were a strong motivator for society itself, whether it be the use of religion to justify hatred, war or prejudice; or, alternately, for love, charity and benevolence. Even the so common, and seemingly utterly nonsecular, phrase “Good Samaritan” has a biblical origin, after all.

Angels and Devils, and Death as well, cavort through the mists of the twilight zone, then, and through the pages of The Twilight Zone too, heavenly hosts and hellish demons each bent on influencing human affairs in one direction or another.

“One for the Angels” (First broadcast: October 9, 1959)

The second episode of The Twilight Zone to be transmitted, again from a Rod Serling script, was also one of the author’s oldest. A version of “One for the Angels” had already been dramatized back in 1954 on the CBS anthology Danger, and before that on WKRC’s The Storm, back in Cincinnati.

Naturally it had been revised since then, restructured to take into account its new surroundings, and audience.

For all the changes, admirers of either of the story’s previous incarnations might still have recognized the character of the sidewalk peddler who, one hot July afternoon, discovers that he is about to die . . . not through the depredations of some dreadful disease, or in the last moments following a tragic accident, but because Mr. Death (Murray Hamilton) effectively tells him it is so. And, in so doing, he unwittingly gives the peddler, Lew Bookman, the opportunity to talk his way out of it by insisting that he has one last piece of unfinished business.

Death usually doesn’t care about such things—what is human ambition to him, after all? Neither can he imagine what possible greater purpose could be wrought from the salesman’s stock in trade—clockwork toys—even if they did include one of the previous year’s top sellers, Robby the Robot, from the movie Forbidden Planet.

But something about the little salesman’s pitch intrigues him . . . as, of course, it was meant to. Bookman is a very good salesman, after all, but before he dies, he says, he needs to prove that he is the greatest, by making his final sales pitch “one for the angels.”

Death agrees to hold off on taking Bookman’s soul, but, to prevent himself from returning home empty-handed, he arranges instead for a little girl (Dana Dillaway) to be hit by a passing vehicle, then waits around for the critically injured child’s soul to become detached from her body. It shouldn’t take long, he reckons, but twenty minutes before he intends returning to the hospital, he is waylaid once again by Lew Bookman.

Once again, poor Mr. Death is left utterly confounded by the man, beguiled into purchasing trinket after trinket, windup toy after windup toy, and missing his midnight appointment with the little girl. Instead of dying, she takes her first step onto the road to recovery, and Bookman knows—he has made the pitch he always dreamed about. Now, he says, Death can take him.

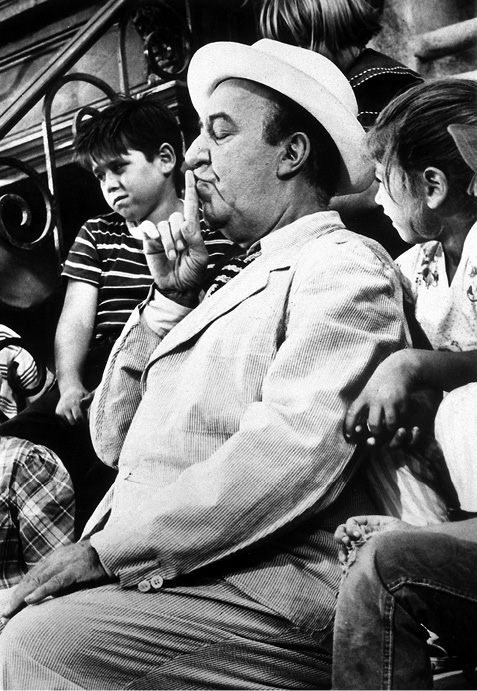

Compared to the reception that awaited the pilot, “One for the Angels” could not help but be underrated, with most reviews focusing on the performances as opposed to the story . . . which, it is fair to say, was scarcely a first-rate effort. Variety spoke for many when it singled out Ed Wynn as the show’s most obvious saving grace, the “whimsical abandon” of his performance ensuring that “the tone never gets heavy.” But that was not necessarily a good thing, as the review also made plain. “The duel for survival gives the play its impact without the shattering emotions.”

Ed Wynn, taking “One for the Angels” in season 2.

CBS/Photofest

“Escape Clause” (First broadcast: November 6, 1959)

Reviewing the previous week’s episode, “Walking Distance,” Variety commented, “Serling’s plays need more than his explanations, fore and aft. It’s a serious takeoff on Alfred Hitchcock’s caricature, but doesn’t help the watcher to un-track himself.”

Unseen at the time, but just days away, “Escape Clause” was to suffer from similar flaws. In an age when the general public still regarded the medical profession with something less than the well-earned cynicism in which it wallows today, and when it was generally believed that people who claimed to be sick were, at the very least, under the weather, the notion that illness could be feigned for any reason was one that had still to find a lot of traction.

It remains an often cloudy issue, even today. In 1959, understanding, or even a common medical consensus was even harder to reach. And so when Rod Serling chose to depict the condition on television that fall, he did so from what can only be viewed fairly through a prism of the era’s own prejudices and convictions.

“You’re about to meet a hypochondriac,” he solemnly declares. “Mr. Walter Bedeker, age forty-four. Afraid of the following: death, disease, other people, germs, draft, and everything else.”

But he is not afraid of illness for his own sake. Hopelessly obsessed with his own self-importance, utterly bound up in his personal achievements, Bedeker has “one abiding concern about society—that if [he] should die, how will it survive without him?”

In fact, as incurable (not to mention insufferable) hypochondriacs go, Bedeker is in rather an enviable situation. Much of his life has been spent in mortal fear of illness and death, but now he has been granted salvation . . . albeit through damnation. In return for immortality and absolute indestructibility, Bedeker has sold his soul to the devil.

The deal itself plays out as a glorious scene, with no exchange more exquisite than where the pair, Bedeker and Satan, are discussing death, not simply as an end of consciousness, but for its physical ramifications, too.

Bedeker first, mourning the relative brevity of life . . . the unfairness, as he sees it, that man should enjoy but “a handful of years and then eternity in a casket down under the ground. The cold, dark ground.”

“With worms, yet,” interjects the Devil.

“Of course with worms,” Bedeker replies. As though to ask, How could there be anything else?

The deal is done, and it’s an eventuality that ought to make Bedeker happy. But it doesn’t. Instead, he grows bored, and determined now not to live but to find the weak point in his newfound lease on life.

Suicide attempt after suicide attempt is unsuccessful, while an attempt to convince the justice system to do the job for him ends in disaster—when his wife is killed in an accident, Bedeker readily confesses to her murder, certain that he will be given the death penalty for his pains. And the electric chair has never failed.

But his defense lawyer clearly hasn’t read the script. He gets Bedeker off with a life sentence instead, and the wretched man is facing an eternity being bars—for life very often tended to mean life in those days, and not just a few years spent paying a debt to society before tightened budgets engineer an early remission.

Which is when the Devil reappears, reminding Bedeker that there is an escape clause, buried in the small print of the contract. Bedeker springs it—and immediately drops dead from a heart attack.

It is an excellent episode, an opinion with which Variety readily concurred. “Here was a little gem. Good work, Rod Serling. This little piece about a hypochondriac who gets tangled up with an obese, clerical devil ranked with the best that has ever been accomplished in half-hour filmed television. One almost wished Serling hadn’t wasted it on a thirty-minute job. It had that elusive virtue of an artistically sound drama embodied in a commercial, unquestionably marketable offering.”

“The Hitch-hiker” (First broadcast: January 22, 1960)

There has never been a shortage of stories warning of the dangers of picking up hitchhikers, from the real-life tragedies of which every teen, and unaccompanied female, is warned; through to the full-blown madness that sparks Rutger Hauer’s portrayal of the eponymous villain of 1986’s The Hitcher; and on to what is possibly the greatest urban legend of them all, the lone figure hitching on a desolate road who is given a lift to what it claims is its destination, only to disappear as the vehicle reaches what turns out to be a graveyard, a ruin or a mystified household, whose child died on that same stretch of road, many years before.

Lucille Fletcher’s chilling “The Hitch-hiker” was a worthy addition to that canon, so much so that it had already been adapted three times for radio before Rod Serling ever dreamed of The Twilight Zone. First heard as a radio play on November 17, 1941, on The Orson Welles Show on CBS Radio, it resurfaced in September 1942, again with Orson Welles, on the anthology Suspense. Six weeks later, the popularity of the initial broadcast demanded a repeat performance, on The Philip Morris Playhouse; and in June 1946, Welles made his fourth appearance in the role, alongside Agnes Moorehead, for The Mercury Summer Theater on the Air.

There was also a family link of sorts, to connect the play to The Twilight Zone. Bernard Herrmann, creator of the theme tune and so much of the music within the show too, was Fletcher’s ex-husband and had scored each of the 1940s broadcasts. In fact, excerpts from his 1946 score would be redeployed in The Twilight Zone’s majestic reprise.

As usual, Serling made a number of changes, most notably changing the protagonist from male to female. A twenty-seven-year-old buyer for a New York department store, Nan Adams is on vacation, driving across country to California when a minor accident on Highway 11 in Pennsylvania slows her down.

The hitchhiker is not, initially, threatening. Not overtly so, anyway. But back on the road following the accident, she has been driving for three days, and always he’s just ahead of her, a nondescript man in a cheap, tatty suit, his thumb forever raised in hope of a ride.

She picks up another hiker, hoping that he will take her mind off the irrational fears that are now gnawing at her mind, but her behavior freaks him out so much that he happily curtails the ride. Finally, Nan stops and calls her mother, just to say hello. Only to discover that her mother is in the hospital in the throes of a nervous breakdown and mourning the death of her daughter Nan, killed in a highway accident.

At the beginning of the episode, we saw Nan having a blowout fixed at a roadside service station. At the end, we realize it was never repaired, for she died when she lost control of the car. And the hiker? He’s sitting in the back seat of her car, and she’s happy to take him wherever he wishes.

“The Chaser”(First broadcast: May 13, 1960)

The short story “Duet for Two Actors” was written by John Collier and first published in the New Yorker of December 28, 1940. A little over a decade later, in February 1951, Robert Presnell Jr. dramatized it for broadcast on Billy Rose’s Playbill Theater, and now he was reworking it once again for The Twilight Zone.

It is a tale of unrequited love, as Roger Shackleforth pledges his troth to a young woman named Leila who barely even recognizes his face when she sees him, and certainly has no intention of falling in love with the man.

So he turns to the renowned (if, perhaps, suspiciously named) Professor A. Daemon, a potion-maker who sells Roger a love potion that is guaranteed to ensure Leila will never ever stray from his side.

A few drops are administered, and it quickly becomes apparent that the potion is efficacious. In fact, it maybe works a little too well. From the moment Leila first imbibes the potion, cunningly concealed in a glass of champagne, she loves Roger like man has never been loved before, clinging so tightly to him that even Roger begins to suffocate beneath her never-wavering passion and devotion. Or, as Serling’s closing narration put it, “Mr. Roger Shackleforth, who has discovered at this late date that love can be as sticky as a vat of molasses, as unpalatable as a hunk of spoiled yeast, and as all-consuming as a six-alarm fire in a bamboo and canvas tent.”

A return visit to the professor, in pursuit of a cure, reveals there is only one—an untraceable poison that costs a small fortune, which Daemon calls “the glove cleaner.” It is fatal.

In one of the series’s most amusing exchanges, Roger begs the professor for a less drastic cure.

Shackleforth: “Professor, I am going out of my ever-loving mind. I can’t stand it anymore!”

Daemon: “Naturally.”

Shackleforth: “Is there such a thing as being loved too much? Isn’t there some way we can just quiet it down a little?”

Daemon: “No.”

Shackleforth: “Well, isn’t there some potion that will transfer a little of this love to someone else? Like a nice cocker spaniel?”

Daemon: “Not a chance. She’s yours.”

Shackleforth: “But she’s so nice to me! She’s so very good!”

Daemon: “I know. ‘The glove cleaner’ is the only way.”

But Roger is desperate. He buys the poison and goes home, fully intending to murder his wife—which is when he discovers she is pregnant. In shock, he lets the poison fall to the floor. And so ends what the closing narration describes as “[a] case history of a lover boy who should never have entered the Twilight Zone.”

“The Last Rites of Jeff Myrtlebank” (First broadcast: February 23, 1962)

Montgomery Pittman both wrote and directed this episode, the story of “a funeral that didn’t come off exactly as planned . . . due to a slight fallout . . . from the Twilight Zone.”

In fact, Serling’s opening words are something of an understatement. Dead and just about to be buried, Jefferson Myrtlebank is perhaps as astonished as the mourners when he awakens and realizes the fate that was about to engulf him.

His funeral is canceled, for obvious reasons, and Jefferson returns to his daily life, only to discover that his concept of that life has changed dramatically. Everything from his eating habits to his work ethic has turned about, and so pronounced are the differences that word is soon spreading through the small Midwest town that something is not quite right about him.

Demonic possession is mentioned, an evil spirit entering Jefferson’s cold, dead body and reanimating the lifeless clay. And the more out of character the townspeople perceive him to be behaving, the more their conviction grows. A mob forms and marches to his home, insisting that he should up sticks and depart.

Of course he argues back, but he uses a very strange argument. Rather than protest his innocence and attempt to sway opinion through logic, he instead plays on their deepest fears. If he is a demon, he explains, then he will behave like one. Either the people leave him and his wife Comfort alone, or his wrath will descend on their homes, their farms, their livelihoods.

The mob flees, even more terrified than they already were, and Jefferson settles back for a smoke. Watch closely, though, and you’ll see how he lights the match that he applies to his pipe. He doesn’t strike it.

Serling’s final words offer us no more solace than that shock ending. Jefferson and Comfort Myrtlebank are still alive today, he says, and their only son . . . he is a United States Senator. A powerful one, as well, “uncommonly shrewd” and inhumanly tenacious.