The Battle of the Black Sea, or as the Somalis call it, Ma-alinti Rangers (The Day of the Rangers), is one that America has preferred to forget. The images it produced of dead soldiers dragged by jeering mobs through the streets of Mogadishu are among the most horrible and disturbing in our history, made all the worse by the good intentions that prompted our intervention. There were no American reporters in Mogadishu on October 3–4, 1993, and after a week or so of frenzied attention, world events quickly summoned journalists elsewhere. President Clinton’s decision just days after the fight to end Task Force Ranger’s mission to Somalia accomplished what he intended; it slammed the door on the episode. In Washington a whiff of failure is enough to induce widespread amnesia. There was a Senate investigation and two days of congressional hearings that produced a partisan report blaming the president and Secretary of Defense Les Aspin, who resigned two months later, but that was it.

Even inside the military, where one might expect to find strong professional interest in the biggest firefight involving American soldiers since Vietnam, there appears to have been little in the way of a detailed postmortem. Proper respects were paid to the dead, and the heroism of many soldiers formally honored, but beyond that, if the battle’s decorated veterans are to be believed, the battle is a lost chapter.

When I began working on this project in 1996, my goal was simply to write a dramatic account of the battle. I had been struck by the intensity of the fight, and by the notion of ninety-nine American soldiers surrounded and trapped in an ancient African city fighting for their lives. My contribution would be to capture in words the experience of combat through the eyes and emotions of the soldiers involved, blending their urgent, human perspective with a military and political overview of their predicament. With the exception of great fiction and several extremely well written memoirs, the nonfiction accounts of modern war I’d read were primarily written by historians. I wanted to combine the authority of a historical narrative with the emotion of the memoir, and write a story that read like fiction but was true. Since I was starting my work three years after the battle, I expected the historical portion of the work had already been done. Surely somewhere in the Pentagon or White House there was a thick volume of after-action reports and exhibits detailing the fight and critiquing our military performance. The challenge, I thought, would be fighting to get as much of it as possible declassified. I was wrong.

No such thick volume exists. While the Battle of the Black Sea may well be the most thoroughly documented incident in American military history, to my surprise no one had even begun to collect all that raw information into a definitive account. So instead of just writing a more vivid version of the story, I found myself in the lucky and exciting position of breaking new ground.

In the months since portions of this book premiered as a newspaper series in The Philadelphia Inquirer, I have spoken to hundreds of active U.S. military officers whom I met at conferences or seminars, or who contacted me seeking copies of the newspaper series or more detailed information about certain aspects of the fight. Among that number have been teachers at the military academies and the Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, the National Defense Analysis Institute, the Military Operations Research Society, officers at the U.S. Marine Corps’ training base at Parris Island, the Security Studies Program at MIT, and even the U.S. Central Command, where the commander, General Anthony Zinni, invited me to take part in a seminar before his staff at MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa, Florida. I was flattered in every instance, but uneasy with the idea that our armed forces would rely on a journalist with no military background to inform them about a battle fought by many men who are still on active duty. As one of the former Delta team leaders remarked after hearing of yet another invitation I’d received, “Why aren’t they talking to us?”

One reason why the battle had not been seriously studied is that the units involved, primarily Delta Force and the Rangers, operate in secrecy, and so much official information about the battle remains classified. It seems the military is best at keeping secrets from itself. But the bigger reason, I suspect, is the same one that sent politicians diving for cover. The Battle of the Black Sea was perceived outside the special operations community as a failure.

It was not, at least in strictly military terms. Task Force Ranger dropped into a teeming market in the heart of Mogadishu in the middle of a busy Sunday afternoon to surprise and arrest two lieutenants of warlord Mohamed Farrah Aidid. It was a complex, difficult, and dangerous assignment, and despite terrible setbacks and losses, and against overwhelming odds, the mission was accomplished.

It was, of course, a Pyrrhic victory. The mission was supposed to take about an hour. Instead, a large portion of the assault force was stranded through a long night in a hostile city, surrounded and fighting for their lives. Two of their high-tech MH-60 Black Hawk helicopters went down in the city, and two more crash-landed back at the base. When the force was extricated the following morning by a huge multinational rescue convoy, eighteen Americans were dead and dozens more were badly injured. One, Black Hawk pilot Michael Durant, had been carried off by an angry Somali mob and would be held captive for eleven days. News of the casualties and images of gleeful Somalis abusing American corpses prompted revulsion and outrage at home, embarrassment at the White House, and such vehement objections in Congress that the mission against Aidid was immediately called off. Major General William F. Garrison’s men may have won the battle, but, as he’d predicted, they lost the war.

The victory was even more hollow for Somalia, although it’s not clear even five years later how many people there understand that. The fight itself was a terrible mismatch. The Somali death toll was catastrophic. Conservative counts numbered five hundred dead among more than a thousand casualties. Aidid could and did claim that his clan had driven off the world’s mightiest military machine. The Habr Gidr had successfully resisted UN efforts to force him to share power. The clan now celebrates October 3 as a national holiday—if such a thing is possible where there is no nation. The pullout of American forces, months after the battle, aborted the UN’s effort to establish a stable coalition government there. Aidid died in 1996 without uniting Somalia under his rule, a victim of the factional fighting the UN had tried to resolve. His clan still struggles with rivals in Mogadishu, trapped in the same bloody, anarchic standoff. Clan leaders I spoke with in that destroyed city in the summer of 1997 seemed to think that the world was still watching their progress anxiously. Photographer Peter Tobia and I were the only guests at the Hotel Sahafi during most of our stay there. We were the first and only Americans who have returned to Mogadishu trying to piece together exactly what happened. I told the Habr Gidr leaders who were hostile to our project that this would likely be their only chance to tell their side of the story, because there weren’t journalists and scholars lined up at the border. The larger world has forgotten Somalia. The great ship of international goodwill has sailed. The bloody twists and turns of Somali clan politics no longer concern us. Without natural resources, strategic advantage, or even potentially lucrative markets for world goods, Somalia is unlikely soon to recapture the opportunity for peace and rebuilding afforded by UNOSOM. Rightly or wrongly, they stand as an enduring symbol of Third World ingratitude and intractability, of the futility of trying to resolve local animosity with international muscle. They’ve effectively written themselves off the map.

Nobody won the Battle of the Black Sea, but like all important battles, it changed the world. The awful price of the arrests of two obscure clan functionaries named Omar Salad and Mohamed Hassan Awale rightly shocked President Clinton, who reportedly felt betrayed by his military advisers and staff, much as an equally inexperienced President Kennedy had felt in 1961 after the Bay of Pigs. It led to the resignation of Defense Secretary Les Aspin and destroyed the promising career of General Garrison, who commanded Task Force Ranger. It aborted a hopeful and unprecedented UN effort to salvage a nation so lost in anarchy and civil war that millions of its people were starving. It ended a brief heady period of post–Cold War innocence, a time when America and its allies felt they could sweep venal dictators and vicious tribal violence from the planet as easily and relatively bloodlessly as Saddam Hussein had been swept from Kuwait. Mogadishu has had a profound cautionary influence on U.S. military policy ever since.

“It was a watershed,” says one State Department official, who asked not to be named because his insight runs so counter to our current foreign policy agenda. “The idea used to be that terrible countries were terrible because good, decent, innocent people were being oppressed by evil, thug-gish leaders. Somalia changed that. Here you have a country where just about everybody is caught up in hatred and fighting. You stop an old lady on the street and ask her if she wants peace, and she’ll say, yes, of course, I pray for it daily. All the things you’d expect her to say. Then ask her if she would be willing for her clan to share power with another in order to have that peace, and she’ll say, ‘With those murderers and thieves? I’d die first.’ People in these countries—Bosnia is a more recent example—don’t want peace. They want victory. They want power. Men, women, old and young. Somalia was the experience that taught us that people in these places bear much of the responsibility for things being the way they are. The hatred and the killing continues because they want it to. Or because they don’t want peace enough to stop it.”

So, for better or worse, the USS Harlan County was turned away from the dock at Port-au-Prince one week after the Mogadishu fight by an orchestrated “riot” of fewer than two hundred Haitians. The U.S. government (and the UN) looked on as genocidal spasms killed a million people in Rwanda and Zaire, and as atrocity was piled on atrocity in Bosnia. There was some cynical posturing in the White House and Congress after the Battle of the Black Sea about never again placing U.S. troops under UN command, when everyone involved understood perfectly well that Task Force Ranger and even the QRF were under direct U.S. command at all times. Even the decision to target Aidid and his clansmen was driven by the U.S. State Department. The single most forceful advocate for Task Force Ranger’s mission in Mogadishu was U.S. Admiral Jonathan Howe, a former deputy on the National Security Council during the Bush administration, who was the top UN official on site in Mogadishu. Task Force Ranger was wholly an American production.

Congress moved quickly to apportion blame. Hadn’t Aspin turned down an initial Task Force Ranger request for the AC-130 gunship, and again, just weeks before the fateful raid, rejected a request for Abrams tanks and Bradley armored vehicles from General Thomas Montgomery, QRF commander? It seems fairly obvious that a light infantry force trapped in a hostile city would be better off with armored vehicles to pull them out, and few aerial firing platforms are as deadly effective as the AC-130 Spectre. Many of the men who fought in Mogadishu believe that at least some, if not all, of their friends would have survived the mission if the Clinton administration had been more concerned about force protection than maintaining the correct political posture. Aspin himself, before he stepped down, acknowledged that his decision on the force request had been an error. The 1994 Senate Armed Services Committee investigation of the battle reached the same conclusions. The initial postmortem on the battle was summed up in a powerful statement to the committee by Lieutenant Colonel Larry Joyce, U.S. Army retired, the father of Sergeant Casey Joyce, one of the Rangers killed.

“Why were they denied armor, these forces? Had there been armor, had there been Bradleys there, I contend that my son would probably be alive today, because he, like the other casualties that were sustained in the early phases of the battle, were killed en route from the target to the downed helicopter site, the first crash site. I believe there was an inadequate force structure from the very beginning.”

This is the line picked up by David Hackworth, the retired U.S. Army colonel who has made a second career writing about the military. Hack-worth devotes a chapter of his 1996 book, Hazardous Duty, to the battle. Pausing to vent his disappointment with not having been invited to observe the action with the Rangers, he calls Garrison “inept” and accuses the White House and military brass of “striking heroic poses,” by not putting “their weapons systems where their mouths were.” Hackworth calculated that tanks would have spared six killed and thirty wounded. There are telling inaccuracies in Hackworth’s account, and it lacks even the pretense of fairness, but the colonel’s critique has nevertheless shaped understanding of the fight both in and out of the military. Garrison is the butt of his assault. He incorrectly suggests that the general was directing the battle from a helicopter overhead, and even quotes one of the platoon sergeants on the ground wishing that he’d had a “Stinger,” to shoot the general down (anyone who fought in Mogadishu that day would have known Garrison was not in the command helicopter). Hackworth concludes that Garrison should have refused to conduct the operation when the initial force package was trimmed. He quotes Joyce as follows: “Initially, I gave Garrison the benefit of the doubt, but the more Rangers I’ve talked to, the clearer it became that he had no good reason to launch the raid the way he did. The tactics were completely flawed. Garrison was a cowboy going for his third star at the expense of his guys.”

From a man who lost his son in the fight, this is a terrible accusation.

I lack the standing to critique the military decisions made by Garrison and his men that day, but the work I have done on Black Hawk Down does qualify me to report authoritatively on the memories, feelings, and opinions of the men who fought. I have interviewed more Rangers, Delta soldiers, and helicopter pilots who were involved in the battle than anyone, and I have yet to meet one who expressed the opinions of the mission or of Garrison reported by Hackworth. The men who undertook the raid on October 3 were confident of their tactics and training and committed to their goals. While many offered incisive criticism of decisions large and small made before and during the fight, and differed substantially with their commanders on some points, they remain proud of successfully completing their mission. I was struck by how little bitterness there is among the men who underwent this ordeal. What anger exists relates more to the decision to call off the mission the day after the battle than anything that happened during it. The record shows that in the weeks prior to this raid, Garrison took more heat for being too careful about launching missions than doing so recklessly. The general, who retired in 1996 after a stint heading the JFK School of Special Warfare at Fort Bragg, is held in universally high regard by the men who served under him.

Garrison took full responsibility for the outcome of the battle in a handwritten letter to President Clinton the day after the fight. This letter has been called a ploy by the general’s critics, although one strains to see what advantage he gained by writing it. It is a document that speaks plainly for itself, the honorable act of an honorable man—and one who clearly feels no shame for the way he or his men conducted themselves in the fight:

I. The authority, responsibility and accountability for the Op rests here in MOG with the TF Ranger commander, not in Washington.

II. Excellent intelligence was available on the target.

III. Forces were experienced in area as a result of six previous operations.

IV. Enemy situation was well known: Proximity to Bakara Market (SNA strongpoint); previous reaction times of bad guys.

V. Planning for the Op was bottom up not top down. Assaulters were confident it was a doable operation. Approval of plan was retained by TF Ranger commander.

VI. Techniques, tactics and procedures were appropriate for mission/target.

VII. Reaction forces were planned for contingencies: A.) CSAR on immediate standby (UH60 with medics and security).

VIII. Loss of 1st Helo was supportable. Pilot pinned in wreckage presented problem.

IX. 2nd Helo crash required response from the 10th Mtn. QRF. The area of the crash was such that SNA were there nearly immediately so we were unsuccessful in reaching the crash site in time.

X. Rangers on 1st crash site were not pinned down. They could have fought their way out. Our creed would not allow us to leave the body of the pilot pinned in the wreckage.

XI. Armor reaction force would have helped but casualty figures may or may not have been different. The type of men in the task force simply would not be denied in their mission of getting to their fallen comrades.

XII. The mission was a success. Targeted individuals were captured and extracted from the target.

XIII. For this particular target, President Clinton and Sec. Aspin need to be taken off the blame line.

William F. Garrison

MG

Commanding

While the facts support Garrison’s accounting overall, I believe he is wrong in this letter on several counts. Only part of points IV and VII are supported by the evidence. Aidid’s tactics were well-known, and the task force’s planning was effective, but only to a point. The Black Hawk helicopter proved more vulnerable to RPG fire than anticipated. Once two of them crashed (three others were crippled but made it back to friendly ground), the task force’s “techniques, tactics and procedures” were stretched beyond their limits. There was clearly insufficient reaction force standing by to rescue the pilots and crew of Super Six Two, Michael Durant’s helicopter. The CSAR bird was the primary contingency for a helicopter crash. It was a well-stocked, superbly trained chopper full of expert rescuers and ground fighters. They were deployed minutes after the crash of Cliff Wolcott’s Super Six One, and were instrumental in rescuing a portion of the crew and recovering the bodies of Wolcott and copilot Donovan Briley. But when Durant’s Black Hawk crashed twenty minutes later, there was no such rescue force at hand. Durant and his crew had to await (tragically, as it turned out) the arrival of a ground rescue force.

Prior to launching the mission, Garrison had alerted the 10th Mountain Division, the QRF, but had decided to let them stay at the UN compound north of the city instead of moving them down to the task force’s airport base. They were promptly summoned after Wolcott’s Black Hawk crashed, but moved to the Ranger base by such a roundabout route (avoiding crossing through the city) that they didn’t arrive until fifty minutes after the first helicopter crash (almost a half hour after Durant’s helicopter went down). So for the first thirty minutes Durant and his crew were on the ground, the only rescue force Garrison could muster was a hastily assembled convoy comprised mostly of support personnel, well-trained soldiers all, but men whom no one anticipated throwing into the fight. Ultimately neither this convoy nor the QRF could fight their way in. They were barred by blockades and ambushes that Aidid’s militias had plenty of time to prepare. The task force knew that it would encounter trouble if it took longer than thirty minutes to get in and out of the target, but few anticipated how many RPGs Aidid’s fighters would bring to the fight. The price was paid in downed Black Hawks.

Garrison’s point X is also debatable. The men I interviewed who spent the night around the first crashed Black Hawk say they were pinned down. In strictly military terms, being pinned down means a force can do nothing. Arguably, if Task Force Ranger’s commanders had wanted to move the force out of the city they could have. More intensive air support was available in the form of Cobra attack helicopters attached to the QRF. But no such decision was made, and from the perspective of the men on the ground, they were pinned down. This is the opinion of everyone I interviewed, from the ranking officers to the lowliest privates. While it may have been possible to fight their way back to the base on foot, the men believe they would have sustained terrible losses. The men on the lost convoy took better than 50 percent casualties moving through the streets in vehicles. The force at crash site one would have had to carry their dead and wounded. The men holed up with Captain Steele at the southern end of the perimeter on Marehan Road balked at having to move one block on foot at the height of the battle. There is no doubt Garrison’s men, if so ordered, would have tried to fight their way out, but they stayed put for reasons that went beyond loyalty to the pinned body of Chief Warrant Officer Cliff Wolcott. Arguing otherwise puts a noble cast to the predicament, but falls short of the facts.

The rest of Garrison’s statement squares well with the facts. The president and Secretary of Defense of course bear ultimate responsibility for any actions of the U.S. military, but without the advantage of hindsight, their decisions regarding the deployment of Task Force Ranger are defensible. Trimming the AC-130 gunship from the initial force request, in light of growing congressional pressure to bring the troops home from Somalia, seems particularly so. Garrison himself felt the gunship was not only unnecessary, but likely to be a less effective firing platform over a densely populated urban neighborhood than the AH-6 Little Birds. If both the Little Birds and the gunship had been in the air, one or the other would have been severely restricted. The small helicopters, flying below the gunship, would have had to clear out to avoid crossing the gunship’s fire. As it was, the Little Birds provided extremely effective air support throughout the battle. To a man, the soldiers pinned down around the first crash site credit brave and skillful Little Birds’ pilots with keeping the Somali crowds at bay. The Somali fighters we interviewed in Mogadishu agreed. They believe the helicopters were the only thing that prevented a total rout of the pinned-down force. Soldiers trapped around the wrecked chopper understandably found themselves longing for the devastating firepower of the AC-130, which could have carved out a corridor of fire for their escape. But command concerns about limiting collateral damage were legitimate. The corridor of fire envisioned by the men on the ground would have pulverized a wide swath of Mogadishu, likely killing many more non-combatants than Aidid’s fighters. Support for the gunship was lukewarm on up the ranks, all the way to General Colin Powell, who in his final weeks as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff acquiesced without complaint to the decision. Interviewed for this book, Powell said that while he formally endorsed the entire force request, even in retrospect he could not fault Aspin’s decision to trim the gunship.

Garrison’s task force never requested or envisioned armor as part of its force package. Its tactics were to strike with surprise and speed, and up until October 3, those tactics worked. It is fair for military experts to criticize Garrison’s judgment in this, but hardly fair to accuse Aspin of turning down a request the task force never made. General Montgomery asked for Abrams tanks and Bradley vehicles in late September for his QRFs, and these were turned down, again because of pressure in Washington to lower, not raise, the American military presence in Mogadishu. It is easy to dismiss these pressures as effete concerns, but strong congressional support is vital to sustain any military venture. In our system of government, everything requires a balancing act. At that point, any move that appeared to be deepening America’s commitment to the military option in Mogadishu weakened support for it. Even if Montgomery had gotten his Bradleys, it’s questionable what impact they would have had in the battle. It is doubtful they would have been in place by October 3. Since they would have been assigned to the 10th Mountain Division, they would not have been part of the Ranger ground reaction force. Lieutenant Colonel Joyce has argued that Bradleys might have saved his son’s life, but since the armor would have been assigned to a unit across the city that was not thrown into the fight until after Sergeant Joyce was killed, it’s hard to see how. The rescue force that finally did extricate the men pinned down at crash site one came in with armor, Pakistani tanks and Malaysian APCs. It may have arrived faster if the QRF had been equipped with the superior Bradleys, but the one soldier who died awaiting rescue, Corporal Jamie Smith, bled to death early in the evening. The rescue column would have had to have left four or five hours before it did to save his life, assuming surgeons could have saved him—by no means a definite thing. Again, the quarrel is over Garrison’s call, not with weak-kneed Washington politicians undercutting forces in the field. Maybe Garrison, General Wayne Downing, General Joseph Hoar, General Powell, and the rest of the military command should have insisted on armor and the AC-130 from the start. They didn’t. I believe these are issues over which well-meaning military experts differ. But it was, as the general noted in his letter, his call.

The suggestion that Garrison and his men should have refused to fight without getting their full force request puts me in mind of General George McClellan, whose battle-shy Union army stayed safely encamped for years demanding more and more resources. President Lincoln finally fired him for suffering a terminal case of “the slows.” The men of Task Force Ranger were daring, ambitious soldiers. They were more inclined to think in terms of working with what they had than refusing to work until they got everything they wanted.

As battles go, Mogadishu was a minor engagement. General Powell has pointed out that the deaths of eighteen American soldiers in Vietnam would not have even warranted a press conference. Old soldiers may snort over the fuss generated by this gunfight, but it speaks well of America that our threshold for death and injury to our soldiers has been so significantly lowered. This does not mean that military action is never worth the danger, or the price. Our armed forces will be called upon again to intervene in obscure parts of the world—as they already have in Bosnia. To prepare for these twenty-first-century missions, there are probably few more important case studies than this one.

The mistakes made in Mog weren’t because people in charge didn’t care enough, or weren’t smart enough. It’s too easy to dismiss errors by blaming the commanders. It assumes there exists a cadre of brilliant officers who know all the answers before the questions are even asked. How many airborne rescue teams should there have been? One for every Black Hawk and Little Bird in the sky? Some of the failures deserve further study. During the battle, efforts to steer the lost convoy from the air turned into a black comedy. At risk of a cliché, how is it that a nation that could land an unmanned little go-cart on the surface of Mars couldn’t steer a convoy five blocks through the streets of Mogadishu? Why did it take the QRF fifty minutes to arrive at the task force’s base when things started to go bad? Shouldn’t they have been better positioned at the outset? But these are all questions that are only obvious in retrospect. The truth is, Task Force Ranger came within several minutes of pulling off its mission on October 3 without a hitch. If Black Hawk Super Six One had not been hit, the “bad” choices made by Garrison would have been called bold. We will never know if Admiral Jonathan Howe was right to believe a lasting peace might have been achieved in Somalia if Aidid had been captured or his clan dismantled as a military force. It seems unlikely. In the years since the warlord’s death, little in Mogadishu has changed. The Habr Gidr is a large and powerful clan planted deep in Somalia’s past and present political culture. To think that 450 superb American soldiers could uproot it violently, thereby clearing the way for, as General Powell puts it, “an outbreak of Jeffersonian democracy,” seems far-fetched. In the end, the Battle of the Black Sea is another lesson in the limits of what force can accomplish.

I began working on this story about two-and-a-half years after the battle was fought. I had been intrigued by the early accounts of the fight, both as a citizen and as a writer. It was clearly an important and fascinating episode, one with tragic consequences for many and lasting implications for American foreign policy. Given the fierce but limited nature of the gunfight—a small force of Americans pinned down overnight in an African city—I realized that it might be possible to tell the whole story. But the undertaking intimidated me. I had no military background or sources, and assumed that someone with both would tell the story far better than I could.

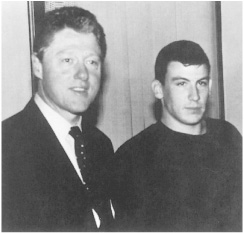

Nevertheless I remained curious enough to read whatever stories I saw about the incident. I was especially intrigued by President Clinton’s subsequent struggles to deal with it. Particularly poignant were newspaper accounts I read of Clinton’s meetings with the parents of the men killed in the battle. Larry Joyce and Jim Smith, the father of Corporal Jamie Smith, had reportedly questioned the president sharply in one of those meetings. I wondered about the informal visit the president paid to soldiers wounded in Mogadishu as they recuperated at Walter Reed Army Hospital. How did those men feel about meeting with the man who had sent them on the mission, and then abruptly called it off? At the Medal of Honor ceremony for the two Delta soldiers, I read that the father of posthumous honoree Sergeant Randy Shughart insulted the president, telling him he was not fit to be commander in chief.

When I was asked by The Philadelphia Inquirer to profile President Clinton in its magazine as he ran for reelection, I tried to answer some of these questions. Interviewing some of the families for an account of their session at the White House, I drove up to Long Valley, New Jersey, one spring afternoon to meet with Jim Smith, a retired U.S. Army captain and former Ranger who had lost a leg in Vietnam. Jim and I sat in his den for several hours. He described the meeting with Clinton, and then talked at length about his son Jamie, how it had felt to lose him, and what little he knew about the battle and how his son had died. I left his house that day determined to find out more.

My initial requests to the Pentagon media office were naive and went nowhere. I filed Freedom of Information requests for documents that, two years later, I have not received. I was told the men I wanted to interview were in units off-limits to the press. My only hope of finding the foot soldiers I wanted was to ask for them by name, and I knew only a handful of names. I combed through what little had been written about the battle, and submitted the names I found there, but I did not receive a response. Then Jim Smith sent me an invitation. The army was dedicating a building at the Pixatinny Arsenal near his home in memory of Jamie. I debated whether to drive up. It would take the whole day and, with my lack of success, the story had receded in priority. Still, I had been moved by my conversation with Jim. I have sons just a few years younger than his Jamie. I couldn’t imagine losing one of them, much less in a gunfight someplace like Mogadishu. I made the drive.

And there, at this dedication ceremony, were about a dozen Rangers who had fought with Jamie in Mogadishu. Jim’s introduction helped break down the normal suspicion soldiers have for reporters. The men gave me their names and told me how to arrange interviews with them. Over three days at Fort Benning that fall I conducted my first twelve interviews. Each of the men I talked to had names and phone numbers for others who had fought there that day, many of them no longer in the army. My network grew from there. Nearly everyone I contacted was eager to talk. In the summer of 1997, the Inquirer sent Peter Tobia and me to Mogadishu. We flew to Nairobi, paid our weight in khat, climbed in the back of a small plane with sacks of the drug, and flew to a dirt airstrip outside Mogadishu. Accompanied by Ibrahim Roble Farah, a Nairobi businessman and member of the clan, we spent just seven days in the city, long enough to walk the streets where the battle had taken place and to interview some of the men who had fought against American soldiers that day. We learned how Somalis had perceived the sometimes brutal tactics in the summer of 1993, as UN troops led a clumsy manhunt for Aidid, and how widespread appreciation for the humanitarian intervention had turned to hatred. Peter and I left with a feel for the place, for the futility of its local politics, and some insight into why Somalis fought so bitterly against American soldiers that day.

In the months after I returned, I found military officers who were eager to hear what I could tell them about the Somali perspective, and about the battle. My work from the ground up eventually led me to a treasure of official information. The fifteen-hour battle had been videotaped from a variety of platforms, so the action I had painstakingly pieced together in my mind through interviews could be checked against images of the actual fight. The hours of radio traffic during the battle had been recorded and transcribed. This would provide actual dialogue from the midst of the action and was invaluable in helping to sort out the precise sequence of events. It also conveyed, with frightening immediacy, the horror of it, the feel of men struggling to stave off panic and stay alive. Other documents fleshed out the intelligence background of the assault, exactly what Task Force Ranger knew and was trying to accomplish. None of the men on the ground, caught up completely in their own small corner of the fight, had a complete vision of the battle. But their memories, combined with this documentary material, including a precise chronology and the written accounts of Delta operators and SEALs, made it possible for me to reconstruct the whole picture. This material gave me, I believe, the best chance any writer has ever had to tell the story of a battle completely, accurately, and well.

Every battle is a drama played out apart from broader issues. Soldiers cannot concern themselves with the forces that bring them to a fight, or its aftermath. They trust their leaders not to risk their lives for too little. Once the battle is joined, they fight to survive as much as to win, to kill before they are killed. The story of combat is timeless. It is about the same things whether in Troy or Gettysburg, Normandy or the Ia Drang. It is about soldiers, most of them young, trapped in a fight to the death. The extreme and terrible nature of war touches something essential about being human, and soldiers do not always like what they learn. For those who survive, the victors and the defeated, the battle lives on in their memories and nightmares and in the dull ache of old wounds. It survives as hundreds of searing private memories, memories of loss and triumph, shame and pride, struggles each veteran must refight every day of his life.

No matter how critically history records the policy decisions that led up to this fight, nothing can diminish the professionalism and dedication of the Rangers and Special Forces units who fought there that day. The Special Forces units showed in Mogadishu why it is important for the military to keep and train highly motivated, talented, and experienced soldiers. When things went to hell in the streets, it was in large part the men of Delta and the SEALs who held things together and got most of the force out alive.

Many of the young Americans who fought in the Battle of Mogadishu are civilians again. They are beginning families and careers, no different outwardly than the millions of other twenty-something members of their generation. They are creatures of pop culture who grew up singing along with Sesame Street, shuttling to day care, and navigating today’s hyper-adolescence through the pitfalls of drugs and unsafe sex. Their experience of battle, unlike that of any other generation of American soldiers, was colored by a lifetime of watching the vivid gore of Hollywood action movies. In my interviews with those who were in the thick of the battle, they remarked again and again how much they felt like they were in a movie, and had to remind themselves that this horror, the blood, the deaths, was real. They describe feeling weirdly out of place, as though they did not belong here, fighting feelings of disbelief, anger, and ill-defined betrayal. This cannot be real. Many wear black metal bracelets inscribed with the names of their friends who died, as if to remind themselves daily that it was real. To look at them today, few show any outward sign that one day not too long ago they risked their lives in an ancient African city, killed for their country, took a bullet, or saw their best friend shot dead. They returned to a country that didn’t care or remember. Their fight was neither triumph nor defeat; it just didn’t matter. It’s as though their firefight was a bizarre two-day adventure, like some extreme Outward Bound experience where things got out of hand and some of the guys got killed.

I wrote this book for them.

Group shot of Task Force Ranger without Delta Force. Humvees are in rear. Courtesy: David Diemer.

Black Hawk Super Six Four, piloted by CWO Mike Durant, moves in from the ocean over Mogadishu. Courtesy: Shawn Nelson.

Rangers Alan Barton, Ron Galliette, and Rob Phipps pose after returning from a night mission. Courtesy: Shawn Nelson.

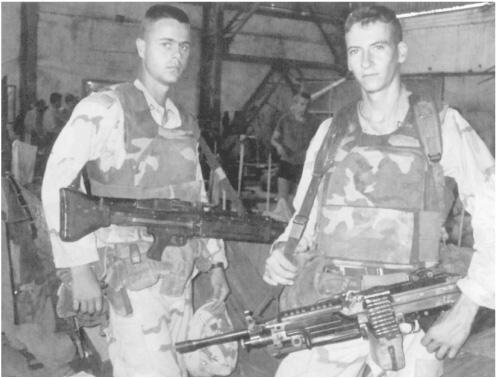

Rangers Jamie Smith and Aaron Williamson in the Mogadishu hangar. Courtesy: James Smith, Sr.

Ranger Keni Thomas aboard a Black Hawk heading out on a mission. Courtesy: Jeff Young.

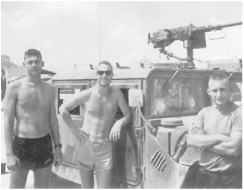

(left to right) Ranger Joe Harsoky, Air Force Combat Controller Dan Schilling, and Ranger Mike Pringle posing before their Humvee, which led the Lost Convoy through the city. Courtesy: Dan Schilling.

A Black Hawk flares before landing on one of the many practice missions in Mogadishu’s dunes. Courtesy: Dale Sizemore.

The only photograph taken from the ground during the battle on October 3. It was snapped looking west from Chalk One’s position at the southeast corner of the target block. Target building looms in the background to the right. Courtesy: Jim Lechner.

Rangers pose in a Humvee topped with a Mark-19. Courtesy: Clay Othic.

Rangers Brian Heard (left) and David Floyd pose in the hangar prior to a mission. Courtesy: Dale Sizemore.

Maj. Gen. William F. Garrison, commander of Task Force Ranger, as he testified before the U.S. Senate committee in 1994. Courtesy: Associated Press.

Ranger Clay Othic posing behind the .50 caliber machine gun in the turret of a Humvee. Courtesy: Dan Schilling.

Ranger Lorenzo Ruiz, who was killed after taking the wounded Othic’s place in the Humvee turret. Courtesy: Dale Sizemore.

President Clinton with Ranger Scott Galentine at Walter Reed Army Hospital. Galentine had his severed thumb sewn back onto his hand. Courtesy: Shawn Nelson.