9

POLICE BATTALIONS: LIVES, KILLINGS, AND MOTIVES

IN SURVEYING THE genocidal contributions of Police Battalion 101 and other police battalions, it becomes easy to view the perpetrators only through the prism of their murderous deeds. This produces some distortion. The extraordinary character of the killing operations, not surprisingly, leads many to consider the perpetrators and their deeds in isolation, sequestered from the rest of human social activity, from the "normal" workings of society, in part because the genocidal deeds seem not to inhabit the same social or moral universe but to belong to a special sub-universe of reality. This can lead to caricature of the perpetrators and their lives. These Germans partook in activities other than genocidal slaughter, and they lived a social existence. Understanding them and their deeds requires that the non-killing aspects of their lives be acknowledged and investigated.

Police battalions did not kill in a social or cultural vacuum. The Germans had rapidly constructed for themselves an institutional network and cultural existence in Poland that was, in its essence, autonomous from Poles (not to mention Jews), as befitting self-conceived Übermenschen who had come to displace "subhumans" and to remake conquered territory in their own image. In fact, an elaborate German cultural life in Poland was the locus for police battalion existence in Poland. After slaughtering unarmed Jews by the thousands, the police battalion men returned to the more conventional type of German cultural life. Their cultural activities—the police's "clubs, recreation centers, and canteens,"1 the sporting events, movies and plays, religious activities, emotional attachments, and moral discussion and injunction— present a stark, even jarring, contrast to their apocalyptic deeds.

Even the routine orders that were circulated by the various institutional commanders, as incomplete and schematic as they were, convey that these genocidal executioners were not the clichéd, atomized individuals that they are often asserted to have been—and that virtually all people today probably conceive them to have been. "Regimental Order No. 25" of Police Regiment 25, which was distributed to its subordinate units, including Police Battalion 65 and Police Battalion 101, gives some sense of the character of the non-killing life that the men of police battalions led. Six items are contained in the order's two pages. The first item reports the results of a race: "On Sunday, October 18, 1942, and October 25, 1942, a team of the Motorized Gendarme Battalion participated in the autumn track meet in Radom." It names the four team members who "in the 'open class' beat the Radom Luftwaffe in both 4,000 meter races, achieving the day's best times." Another man in the Motorized Gendarme Battalion took second place in a different event. The regimental commander adds: "I extend to the winners my congratulations on their achievements."

The second item of the "Regimental Order" lists, as a matter of routine, the officer and enlisted man who would be on duty for each day of the coming week. The third item tells of the resumption of train service from Cracow to Krynica, "for the promotion of the spa Krynica." It gives the winter train schedule to this recreational destination, which was hours away. The fourth item, entitled "A play for the men," announces another recreational opportunity:

On November 3 and 4 at 8 PM in the House of the NSDAP [Nazi Party] in Lublin the theater troupe of the police

"Ostermänn"—better known as "Berlin Youth" will perform for the members of the Order Police and their families.

—Admission is free.—

The fifth and sixth items concern health measures, one ordering that infectious diseases be reported immediately and the other alerting the units of upcoming notices about typhus, which are supposed to be posted.

"Regimental Order 25," which is one unremarkable example of the weekly orders that went out to all of the regiment's units, presents a picture at odds with the one-dimensional image that is easy to develop of the perpetrators and of the institutions in which they operated. The regimental commander is naturally proud of his men's athletic achievements against the Luftwaffe, which took place in distant Radom. He informs his men of their recreational opportunity in Krynica, a noted southern Polish resort famous for its mineral baths. He invites them with their families, at no charge, to an evening of entertainment, to be provided by the police's own theater troupe.

"Regimental Order 25" emanated from Lublin on October 30, 1942, radiating outward to the regiment's units strewn about the district. 2 What were these units undertaking in the war against the Jews around the time when they received this notice of leisure activities?

Police Battalion 101 was in the middle of its methodical genocidal decimation of the Jews in its region, having just three days before completed one of its deportations of Jews from Miȩdzyrzec to a death camp. Police Battalion 65 was in high gear, shooting and deporting to Auschwitz the Jews of Cracow and its environs. Police Battalion 67 was decimating the Jewish communities around Bilgoraj and Zamość. Around this time, Police Battalion 316 was slaughtering two thousand Jews of Bobruisk.

The "Regimental Order" of October 25, 1942, was in no sense out of the ordinary. Notices of athletic events,3 cultural opportunities, 4 and other leisure activities were normal items for the genocidal killers to receive. At the end of June 1942, for instance, the men learned of the swimming pool's operating hours in Lublin, and of the tennis opportunities open to them. Although, the men had to furnish their own rackets, "a small number of tennis balls are available at the SS and Police Sports society, Ostlandstr. 8c, Room 2. They can be borrowed for a fee. On account of the difficulty in obtaining them, tennis uniforms are not obligatory. However, the tennis court can be entered only in sports shoes with rubber soles." 5 The circulars sent to the men of police units informed them of all kinds of routine matters, such as when and where coal for winter heating would be distributed,6 as well as of new administrative procedures. They communicated the latest instructions for the treatment, including killing, of "hostages" and for operations against Jews. It is in itself noteworthy and telling that such "normal" lethal matters were discussed in paragraphs sitting side by side with discussions of leisure activities.

The orders also contained all sorts of instructions about the men's conduct both in their duty and in their leisure time, often admonishing them for breaking regulations or for not living up to expectations. In one order, the commander informed his men that it had come to his attention that "large quantities of wrapping material, mineral water and other bottles lie about." The profligacy of the men incensed him: "It is irresponsible," he wrote, "that in the present raw material and supply conditions, the responsible persons do not endeavor to make immediate renewed use of the empty containers and the wrapping material." He promised to hold responsible all those who continued to waste such materials.7 It appears from this and the many other admonitions that were responses to breaches of superior orders or decorum that these Germans were hardly automatons, hardly perfectly obedient subordinates; but like others, they were inconstant and selectively inattentive to duty, regulations, and social norms.

The Germans in the police units stationed in Lublin had many opportunities to attend not only police cultural functions but also those of the armed forces. The men of Police Regiment 25 did not always conduct themselves in a satisfactory manner when in attendance, as this reprimand from the regimental commander attests:

By issuing free tickets to theater performances, concerts, movie showings, the armed forces performances are attended also by members of the Uniformed Police, who find no pleasure in them and who manifest their displeasure by loud remarks, laughter, and disorderly conduct. Such behavior bespeaks a disregard for other spectators as well as for the artists, and is apt to lower the reputation of the Uniformed Police. It is incumbent upon the unit commanders and office managers to issue pedagogical instructions to the effect that everyone should behave correctly and wait quietly for the end of the performance or for the next intermission.8

Although present in institutions where people routinely conducted themselves decently, where no external authority was as a rule needed for the normal decorum of minimal civility to prevail, the Germans of Police Regiment 25, living by the supposedly strict norms of a police institution, violated the social rules of everyday existence in a gross manner. What does this tell us about these men, about their devotion to rule-following, about the nature of their parent institution, which they clearly did not fear? In the same "Regimental Order," another reprimand is conveyed, this time not just for inconsiderate, anti-social activity but for illegal acts: "Members of the Order Police who were assigned to the protection of the harvest unlawfully hunted wild boars. I must point out that every kind of illegal hunting will be treated as poaching. Repeaters will be called to account."9

These institutional orders, even with the scanty information that they contain—so paltry in volume and variety in comparison to the reality of the stream of the Germans' daily actions while on duty and at leisure—are still sufficient to suggest a number of conclusions: The stereotypes about the perpetrators that have emerged whole out of thin air exist, to a great extent, in an empirical vacuum. Little attempt has been made by those who have created or countenanced such erroneous stereotypes to confront the institutional and social context of the perpetrators' actions or the fullness of their lives.10

The perpetrators were not robotic killing machines. They were human beings who lived "thick" lives, not the thin, one-dimensional ones that the literature on the Holocaust generally suggests. They had many and complex social relations, and performed a relatively wide variety of daily tasks. They had family at home, friends within their units—some of whom could undoubtedly be classified as buddies—and, in the areas where they were stationed, contacts with Germans in other institutions and with non-Germans as well. Although they were living in the shadows of genocidal slaughter, some significant number of perpetrators must have had their family members with them, as the invitation to the evening with the theater troupe suggests, by explicitly stating that families were welcome. Clearly, Wohlauf and Lieutenant Brand were by no means exceptional in having their wives by their sides. The perpetrators also had love affairs. One of the men of Police Regiment 25 began a relationship with the woman who was to become his wife, while he served as a regimental clerk, recording, among other items, the progress of the regiment's genocidal killing. She was working in the office of the commander of the Order Police in Lublin, first as a telephone operator and then as a secretary for the operations unit where they planned the genocidal operations." Theirs was not a society devoid of women. The men of Police Battalion 101 had, for example, frequent "social evenings" (geselligen Abenden), where one of the men, a violinist, remembers that Dr. Schoenfelder, the healer of Germans who had given instructions in the technique of killing Jews, played "the accordion marvelously and did so with us frequently." 12 They had musical afternoons, like one that Second Company enjoyed in Miedzyrzec, the site of their most frequent and largest killing operations. Four surviving photographs show a small group of musicians playing from a second-story porch before a yard filled with the company's men, who are si tting or milling about. For their further recreation, the men of Police Battalion 101 had a bowling alley, which they fashioned in their own workshop. The game that they played, Kegeln, like bowling, is a quintessentially social game, where a small group of men, typically from two to six, congregate at one end of the alley and match their skills, amid rooting and cheering, against the pins and one another.13

The perpetrators had free time which they could use, depending on where they were stationed, for a variety of activities that allowed, even prompted, them to activate their moral faculties and to take a personal, individual stance. Whether they were in church, at a play, or in a small group, say, drinking in a bar and surveying the terrain of their lives, the perpetrators lived in a moral world of contemplation, discussion, and argument. They could not but react, have opinions, and pass judgment on the events large and small unfolding before them daily. Some of the men went to church, prayed to God, contemplated the eternal questions, and recited prayers which reminded them of their obligations to other humans; the Catholics among them took communion and went to confession.14 And when they went at night to their wives and girlfriends, how many of the killers discussed their genocidal activities?

The Germans in police battalions were also not slavishly devoted to orders, as their superiors' frequent reprimands concerning both their inattentiveness and outright transgressions indicate. Their penchant for recording photographic images of their heroics against Jews was combated by a stream of orders prohibiting such activity, but to little avail.'5 These were not robotic Germans; they had their opinions about the rules that governed them, and these views obviously informed their preferences and the choices that they actually made about whether or not to adhere to the rules and, if so, in what manner.

In their postwar testimony, the perpetrators say next to nothing about their leisure activities; their interrogators were interested in querying them about their crimes, not the frequency of their theater visits, the number of goals which they scored in their soccer matches, or what they talked about when relaxing in their social clubs. So the perpetrators are relatively mute on the array of subjects and activities that need to be examined, if the full character of their lives as ideological warriors is to be reconstructed.

Particularly interesting to know would be their reaction to certain orders which they received regarding animals, orders that would have struck any but those beholden to the Nazi antisemitic creed as deeply ironic and disturbing. One regimental order, from August 1942, informs the men that the Generalgouvernement has been declared to be an "animal epidemic region" (Tierseuchengebiet). In light of this, certain procedures for the care of police dogs were prescribed, mainly the mandate to provide strict veterinary examination of the dogs, especially when they traveled to and from different areas. "During the whole time the dog manager must observe his dog extremely closely and bring him to the local police veterinarian upon the slightest symptom of illness or change in the behavior of the animal."16 Concern for the health of police dogs (they were, after all, useful for, among other tasks, the brutalizing of Jews) and for preventing contagious illnesses from spreading is understandable. Did the killers, upon reading this, not reflect on the difference in treatment they were meting out to dogs and Jews? At the slightest hint of illness or irregular behavior exhibited by the dogs, the Germans were directed to whisk the dogs to a veterinarian for care. Jews who were sick, especially the gravely ill, or those who gave the slightest indication of having contagious illnesses, like typhus, made no visits to the doctor. As a rule, the Germans fought Jewish illnesses with a bullet or a social-biologically "sanitizing" trip to the gas chamber. Not only did Germans respond to sickness in dogs and in Jews in diametrically opposed ways, but they also killed healthy Jews, using the pretext of sickness as a formal justification, as a deceptive verbal locution for genocidal killings. In fact, to the Germans, Jews became synonymous with illness, and illness of this sort was seen and treated as cancerous, to be excised from the body social. The transvaluation of values was expressed with pride by one German doctor working in Auschwitz: "Of course I am a doctor and I want to preserve life. And out of respect for human life, I would remove a gangrenous appendix from a diseased body. The Jew is the gangrenous appendix in the body of mankind."17

The desire to prevent illness in police dogs can be seen as having been purely a utilitarian measure. The ties of affection binding one SS general to his dog, however, were also capable of moving genocidal agents to action. In October 1942, the men of Police Regiment 25 learned in a postscript to a regimental order that "a fourteen-month-old yellow German shepherd, answering to the name Harry" had, weeks earlier, jumped from a train near Lublin, and had not yet been recovered. ''All stations," the order continued, "are re- quested to look for the German shepherd so that he be returned to his master."18 The regimental headquarters was to be notified upon the dog's capture. Owing to their missions in search of hidden Jews, most of the men receiving this order were already acclimated to scouring the countryside. Perhaps each kept an eye peeled for the dog, as he combed the terrain for every last Jew. The dog's fate, if indeed he ever was found, was greatly preferable to that of the Jews. In every respect, the Germans would have agreed, it was better to be a dog.

The orders concerning dogs might have provoked the Germans to think about their vocation if their sensibilities had remotely approximated our own; the comparison in their expected treatment of dogs and their actual treatment of Jews might have fostered in the Germans self-examination and knowledge. Yet, however much the reading of these orders about dogs would have evoked disturbing comparisons in non-Nazified people, the effect of the series of orders sent out regarding "cruelty to animals" (Tierquälerei) would have likely been to the non-Nazified psychologically gripping, even devastating.

On June II, 1943, the commander of Police Regiment 25 reprimanded the regiment for not having met regulations in posting the information sheets regarding animal protection (Tierschutz). In light of this negligence, he had concluded that "no attention is paid to the protection of animals." He continued:

One should with renewed strength take measures against cruelty to animals (Tierquälereien) and to report it to the regiment.

Special attention is to be devoted to the beef cattle, since through overcrowding in the railway cars great losses of the animals have occurred, and the food supply has thereby been severely endangered.

The enclosed notices are to be used as a subject for instruction. 19

Genocidal executioners and torturers promulgated and received orders, obviously heartfelt ones, enjoining consideration for animals. The order then discussed the problem of packing cows too tightly into cattle cars! Contrast this with an account from a member of Police Battalion 101 of their cattle car treatment of Jews in Miedzyrzec: "As particularly cruel, I remember that the Jews were jammed into the cars. The cars were stuffed so full that one had to labor in order to close the sliding doors. Not seldom did one have to lend aid with one's feet."20

The bizarre world of Germany during the Nazi period produced this telling juxtaposition between the solicitude owed animals and the pitilessness and cruelty shown Jews.21 Orders not to cram Jews too tightly into cattle cars never came the way of the Germans in Poland who deported Jews to their deaths, typically by using kicks and blows to force as many Jews into the railway cars as was possible. The freight cars carried both cattle and Jews. Which of the two was to be handled more decently, more humanely, was clear to all involved. The cows were not to be crushed in the cars because of the food that they produced. But this was not the only reason. The Germans, throughout this period, took great pains to ensure that animals were treated decently. In their minds, it was a moral imperative.22

However arresting this contrast of cattle cars might be to us, as well as the stream of orders commanding decent, "humane" treatment of animals, they likely were hardly noted as remarkable by the Germans involved. What appear to be ironies, so obvious that they could be missed by none, so cruel that they should have shaken any involved, were undoubtedly lost on the perpetrators. They were too far gone. Their cognitive framework was such that the juxtaposition could not register. With regard to Jews, the perpetrators were each, to quote the title of one of the plays that was performed for their entertainment, a "Man Without Heart" (Mann ohne Herz).23 It is safe to assume that the irony of the title was also lost on them.

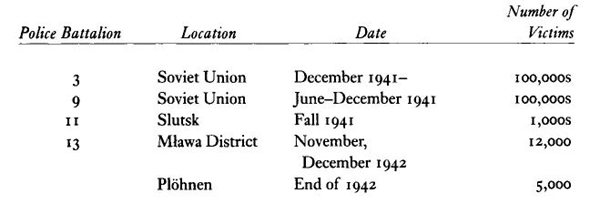

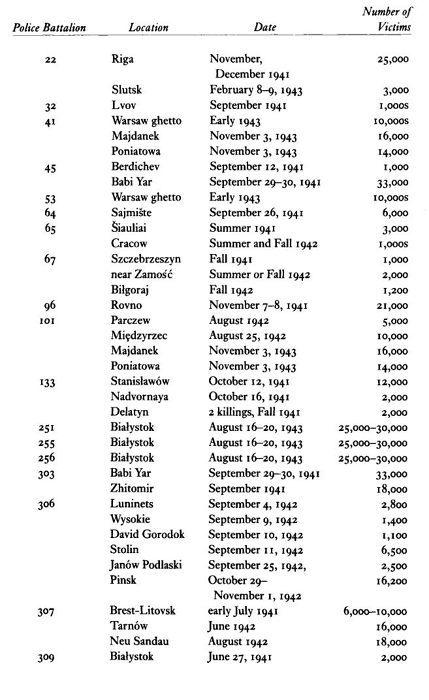

THE HISTORIES PRESENTED here of certain police battalions—of these itinerant, genocidal cohorts of ideological warriors going from one Jewish community to the next in order to obliterate each one's existence—are not isolated or singular examples. Their tales of horrors and willfulness could, in their essential features, be written for a host of other police battalions. The police battalions discussed here (Police Battalions 309, 133, 65, and 101) were not the most murderous of battalions (see the table below), and their men's actions were not exceptional by the brutal and murderous standards that the German police set during the Holocaust. This being the case, what can be said more generally about the overall complicity of police battalions in the Holocaust?

Obviously, not all police battalions perpetrated genocidal slaughter. Many simply never received the orders to participate in killing operations. So the percentage of police battalions that were complicit in genocide is not an illuminating figure, for such tasks were not voluntary in the sense that the regime sent out recruitment notices giving particularly bloodthirsty battalions and men the opportunity to sign up to become genocidal executioners. By chance, some police battalions ended up in killing operations and others did not. No evidence suggests that the regime either hesitated to use police battalions at all for mass killings of Jews or discriminated among police battalions in making such assignments, by screening them according to some criteria of fitness and willingness, or by using any other means that took the character of battalions and their men into account.24 Happenstance accounts for much of why the men of one police battalion killed Jews while those of another did not. Relevant to an analysis of police battalions' role in the genocide, therefore, are the actions of the men only of those police battalions that were ordered to deport Jews to their deaths or to kill them with their own hands.

On this point some general things can be said. A large enough number of police battalions contributed to the Holocaust that their participation in the perpetration of the Holocaust was seen as, and indeed was, absolutely ordinary. The regime routinely turned to police battalions as implementers of the genocidal will. As far as my (considerable but not exhaustive) research has determined, at least thirty-eight police battalions killed or deported Jews to death camps in the stock manner of Police Battalions 65 and 101. (Undoubtedly, more will be uncovered.) The material that exists on some of these battalions is so sketchy that little can be said of the extent and character of their actions, except that they perpetrated mass slaughter of Jews. Of these thirty-eight battalions, at least thirty perpetrated large-scale slaughters or deportations. The following table contains only some of the major killing operations (over one thousand victims) of these thirty battalions. They and other police battalions carried out an enormous number of other killing operations, large and small, that are not listed.25

The men of these police battalions had unequivocal proof that they were being asked to take part not just in some harsh military measure, however just or unjust, such as the killing of one hundred "hostages" from a town in retribution against the local population for having allegedly aided partisans. When slaughtering thousands of people or sending entire communities packed in freight cars to death factories, these Germans did not and could not have had illusions that they were members of something other than a genocidal cohort, even if they might not have articulated it in so many words.

It is hard to say how many Germans were involved in the killing operations of just these police battalions. The precise size of each battalion is not known, and it is not always possible to ascertain how many men of each battalion participated directly in the deportations and killings. Moreover, police battalions had shifting memberships because of transfers and casualties, which certainly increased the number of Germans under the aegis of police battalions complicit in the genocide. Some rough estimates, each of which is undoubtedly low, would be as follows. If the average strength of police battalions is taken to have been five hundred men (which is probably an underestimate), it would mean that nineteen thousand men were members of the thirty-eight police battalions known to have been engaged in the mass slaughter of Jews. In the thirty police battalions known to have carried out large-scale killings, the number of Germans was, by this calculation, fifteen thousand. It cannot be said for sure what percentage of each battalion took part in killings. It is known that battalions that engaged in large-scale killings typically deployed high percentages of their men in the operations. Testimony from many police battalions indicates that everyone in those battalions was so employed. 26 So even if the number of Germans who can be counted as perpetrators is somewhat smaller than the estimates of the number of men in the genocide-abetting police battalions, the numbers are still large. Many of them were "ordinary" Germans.

The composition of individual police battalions made no difference for their performance. Whether battalions were populated mainly by reservists, mainly by professional policemen, or with various admixtures of the two, they carried out their tasks with little variation, and to deadly effect. Whatever the percentage of Party members or SS men among them, the battalions as a whole performed their genocidal jobs in a manner that would have made Hitler proud. In fact, the postwar testimony of the Germans in police battalions reveals little consciousness of differences in attitude or action between those who were either Party or SS members and those who were not. For the men it seems to have been a non-issue, in all likelihood because when it came to their most important activity no difference, certainly no systematic difference, existed between those who belonged to these two leading Nazi institutions and those who did not. Killing Jews was a great leveler, a great equalizer, in Germany during the Nazi period, effacing differences that in other realms of activity normally marked Germans of different backgrounds, professions, and outlooks as being distinct from one another.

The institutional histories of police battalions also were immaterial to their men's effectiveness and willingness as genocidal killers. Whether or not they had seen front-line fighting, whether or not they themselves had confronted the horrors of war and feared for their lives, cannot be discerned from their performances as genocidal killers. Police Battalion 65 killed Jews before it was ordered to the front, where it became encircled, fought for its life, and sustained heavy casualties in the northern part of the Soviet Union. It killed Jews in the Generalgouvernement after its baptism in the sufferings of war. The "brutalization" that the men underwent during the fighting had no appreciable effect on their treatment of Jews. Similarly, none of the evidence suggests that prolonged engagement in genocidal slaughter altered the treatment that the men of police battalions meted out to Jews. Except sometimes for the killers' baptismal massacre, owing to the shock that the killings' gruesomeness administered to the Germans, the Germans' demeanor, their zeal in performing their duty, and the high quality of their apocalyptic product appear to have remained constant throughout their lives in a genocidal cohort. So notions that during the course of the killing the men became progressively disinhibited towards Jews, or more brutish because of the psychological effects on them of repeatedly slaughtering Jews, and that these developments (if they actually occurred) caused them to act towards Jews as they did, are not borne out—indeed, are falsified—by the record.27 Police battalions—the most innocent and most experienced, the most sheltered and the most exposed to privation and danger—killed Jews proficiently, in a manner that would have satisfied the most virulent and pathological antisemites. Hitler and Himmler were pleased.

The Germans in police battalions slaughtered Jews in a variety of formations and settings. They conducted killing operations in battalion strength, in company strength, or sometimes just a platoon at a time. In the very large massacres, they killed in conjunction with other police and non-police units, together with Germans and non-German auxiliaries. In the small ones, they killed in small groups. Sometimes they were supervised by officers; sometimes the enlisted men assigned to the killing operation acted without supervision. No evidence suggests that the size of the killing detail or the degree of officer oversight for a given operation was determined by any consideration other than practical ones, mainly the number of men which they considered necessary for accomplishing the task. The Germans in police battalions just as easily worked in large concert, in medium-size groups, or in groups of two, three, or five. They brought off their assignments whether they were ghetto clearings, deportations, mass shootings, or search-and-destroy missions. These Germans were flexible, versatile, and accomplished in their vocation.

The absence of significant variation in actions among the Germans of different police battalions, either owing to the battalions' membership composition, their histories, or the immediate setting of their deeds, is paralleled by a similar absence of difference between the actions of their men on the one hand, and of the men in the Einsatzkommandos and other SS units on the other. Police battalions and Einsatzkommandos, for example, in addition to their different membership composition, had different corporate identities. Police battalions were formally and mainly devoted to policing and maintaining order. Like the Einsatzkommandos, they also had to secure their assigned areas, which meant fighting the enemies of the regime, but their entire (even if often perfunctory) training and their ethos were that of policemen, if perhaps that of colonial policemen. The Einsatzkommandos, by contrast, were ideological warriors by stated vocation, whose understood reason for being was to exterminate Jews. They also performed other duties, but their prime directive was to kill enemies of the regime. Despite their divergent identities and orientation, police battalions and Einsatzkommandos—in their manner of operating and their treatment of Jews—look very much alike.

In two important respects, police battalions differed from the Einsatzkommandos. The Einsatzkommandos were typically eased into genocidal slaughters by having initially killed Jewish men, sparing them the psychologically more difficult task of killing women and children so as to give them time to become acclimated to their new vocation. This was the case as well for the Germans of a few police battalions that killed during the first phase of the assault on Soviet Jewry. But the Germans of many other battalions received no such stepwise initiation into genocidal annihilation. Considerable numbers of women and children were among their first victims, testing their dedication and their nerves more strenuously. The Germans appear to have learned that, contrary to their original expectations, easing the men into genocidal killing was not necessary. Even if some were initially shocked, most adjusted quickly and easily to the killing. With Police Battalion 101, however, the opposite was the case. At first, they killed mainly women, children, and the aged and infirm, because they sorted out many of the more healthy men for transport to "work" camps. Also, by this time the genocidal enterprise was in full swing and had become such a normal affair that selective killing would have gone against the grain of Aktion Reinhard's spirit and procedures.

Second, police battalions typically, and similarly from the very beginning of their contribution to the genocide, annihilated Jewish ghettos—those German-perceived blights on the social landscape—in the dual sense of killing a ghetto's inhabitants and destroying the social institution. The Germans ferreted out hidden Jews and killed the old and the infirm on the spot, sometimes in their beds. The ghetto clearings, as described above, turned into licentious affairs that bore no resemblance to military activities. From the start, it was clear to everyone involved that no real military rationale was behind these horrific, Dantesque scenes. The ghetto clearings required a willfulness and a degree of initiative that the more orderly, more (if only in appearance) military Einsatzkommando killings of the initial phase did not.28

If anything, then, on the margins, the men in some of the police battalions had a more demanding, more psychologically difficult road to travel. Unlike the Einsatzkommandos, they were not eased into the genocidal killing, and integral to their operations was the emptying of ghettos of all life, with all the brutalities that it entailed. These differences, it is worth emphasizing, did not exist in all cases, and are, in the end, but marginal, if meaningful, differences in degree. Both their significance and their psychological effects upon the perpetrators can be debated. Certainly, however, in light of the genocidal slaughter that was the Germans' essential activity, the differences are eclipsed in importance by the similarities; overall, the convergence in action between police battalions and Einsatzkommandos is remarkable.

The study of police battalions, finally, yields two fundamental facts: First, ordinary Germans easily became genocidal killers. Second, they did so even though they did not have to.

The haphazard method by which the regime filled the ranks of many police battalions was extremely likely to produce battalions stocked with ordinary Germans, people who were, by important measures, broadly representative of German society. The biographical data on the men of Police Battalion 101 confirm that this was indeed the case. Still, an additional sample was taken from two other reserve police battalions that conducted a great deal of killing, Police Battalion 65 and Police Battalion 67, in order to ensure that the composition of Police Battalion 101 was not idiosyncratic. A combined sample of 220 men yielded 49 Nazi Party members, which is 22.3 percent, and 13 SS men, or 6.0 percent. The Party membership percentage for these two battalions was lower than for Police Battalion 101, while the percentage of SS men was slightly higher. Of the 770 men in the total sample from the three battalions, 228 (29.6 percent) had Nazi Party membership and a paltry 34 (4.4 percent) had SS membership. Thus, the degree of Nazification of Police Battalion 101 was, by the measure of these two other battalions, not high for police battalions.

The Germans in police battalions were—by their prior institutional affiliation, their social background, and, with some minor differences, even by their degree of ideological preparation—ordinary members of German society. At least seventeen of the thirty-eight police battalions that perpetrated genocidal killings and fourteen of the thirty that perpetrated large-scale massacres had a significant number of members who were not professional policemen, whose profiles in all likelihood resembled those of the sample, because the manner in which they were recruited was similar.29 Most of them, as the training schedules show, also had very little training, because the Nazi regime and the Order Police did not conceive of the possibility that much further ideological preparation would be necessary in order to gain these men's accedence and willing cooperation in Jew-killing.

Finally, opportunities existed for the men in police battalions individually to avoid killing altogether or at least to remove themselves from continuing as genocidal executioners. It is a demonstrable fact that such opportunities were available to the men of many police battalions, and it is probable—though it is not known—that such opportunities were available to the vast majority of them. Evidence exists for at least eight different police battalions and a ninth similar unit, the Motorized Gendarme Battalion, that the men had been informed that they would not be punished for refusing to kill.30 For Police Battalion 101, the evidence on this point is unequivocal and arresting. The general solicitude that many individual commanders showed their men, by making it possible for so many to extract themselves easily from the killing, was likely reinforced by another source; in light of testimony, it appears that Himmler issued a general order giving dispensation for members of police and security forces to opt out of killing.31 In all probability, the men of police battalions other than these nine were similarly informed about the possibilities to excuse themselves, although they have not revealed this in postwar testimony. Such admissions would be self-indicting. The major who was in charge of the Operations Division of Police Regiment 25 tells of one colonel who requested to be relieved of his duty in Lemberg because his conscience would not permit him to continue with the killing. This colonel was given an important job back in Berlin. The major, who would certainly have become aware if any such instance had occurred in Police Regiment 25, because he was the officer responsible for dealing with such matters, states unequivocally that he knows of no case in the Order Police in which a man who refused to take part in the genocide was punished.32

But even if no announcement had been made to them, the men of police battalions could have taken steps that had some chance of freeing them from these onerous tasks. They could have requested transfers. They could have indicated that they were not capable of this duty. The men of a number of police battalions describe their commanders as having been fatherly, understanding, or kind.33 Surely, they could have approached such a commander and explained to him that the killing of children was just too difficult for them. If worse came to worst, they could have feigned breakdowns. To be sure, isolated attempts to avoid killing were made, yet the evidence suggests that they were few indeed.34

The Germans in police battalions were thinking beings who had moral faculties and who could not fail to have an opinion about the mass slaughters that they were perpetrating. It is significant that, in the voluminous self-exculpating postwar testimony, the former perpetrators' denials of their own participation and approval of the killings are almost exclusively made by the testifying individual with respect to himself. If these numbingly frequent individual denials reflected the true prevailing state of affairs while the killing was taking place, then it would mean that widespread opposition to the killings had existed, and that the men had shared their condemnation among themselves. It could be expected, then, that legions of individual perpetrators, each corroborating the other, would have given testimony about how they and their comrades had discussed the criminality of the mass murder, about how each voiced to the other his lamentation at having been bound to this crime—had such discussions indeed taken place. Yet these sorts of assertions—of the principled opposition by the testifier's comrades to killing— appear hardly at all in the testimony of the men of police battalions. This is true for the battalions for which evidence exists that the men knew that they did not have to kill, and for battalions for which such evidence is absent.

In the end, whether or not it was known in more than nine police battalions that it was possible for the Germans who served in them to refuse to kill without suffering seriously is in itself not of great importance for drawing conclusions about police battalion contribution to the genocide, because those Germans who were informed that they could be excused from genocidal duties killed anyway. The Germans in nine police battalions, totaling 4,500 men or more, did indeed know that they did not have to take part in genocidal killing, yet they, with virtual unanimity, chose to kill and to continue to kill. Significantly, of these nine battalions, all but one were composed predominantly or substantially of reservists. This suggests that the men of other police battalions would have killed no matter what they might have known about the possibility of opting out. No evidence or reason exists to conclude the opposite. The men of these nine battalions form a sample sufficient to generalize with confidence about other police battalions. By choosing not to excuse themselves from the genocide of the Jews, the Germans in police battalions themselves indicated that they wanted to be genocidal executioners.

Why would they have done otherwise, given that they conceived of the Jews as being powerfully evil? Erwin Grafmann, in significant respects the most forthcoming and honest of all the men in Police Battalion 101, 35 was asked why he and the other men had not taken up his sergeant's offer before their first killing foray and excused themselves from the execution squad. He responded that, "at the time, we did not give it any second thoughts at all."36 Despite the offer, it simply never occurred to him and his comrades to accept it. Why not? Because they wanted to do it. Speaking of the Józefów killing, Grafmann asserts unequivocally: "I did not witness that a single one of my comrades said that he did not want to participate."37 Grafmann, in suggesting the degree to which they had assented to their actions, confirms that they had been in the grip of an ideology powerful enough to induce them to kill Jews willingly: "Only in later years did one actually become fully cognizant of what had taken place at the time." He had been so Nazified that only years later (presumably when, sobered, he began to perceive the world through non-Nazi eyes) did he first comprehend what they had committed—a monstrous crime. That what Grafmann meant here was that he and, as he was speaking for them, his comrades were not morally opposed to killing Jews is made clear by his next sentences, in which he explains why he got himself excused from the further killing that day, after he had already shot "between about ten to twenty" Jews: "I requested to be relieved particularly because my neighbor shot so ineptly. Apparently, he always held the barrel of the rifle too high because horrible wounds were inflicted on the victims. In some cases, the entire rear skull of a victim was so shattered that brain matter spattered about. I simply could not look at it any longer."38 Grafmann explicitly emphasizes that it was merely disgust that made him want to take a breather, and utters not a word to indicate that either he or the other killers thought the killing to be immoral. As Grafmann said later, at his trial, it was only afterwards that the thought first "occurred to me that it [the killing] was not right."39

Another member of the battalion, in the middle of discussing "bandits," explains why they (presumably also Grafmann) did not have any moral qualms about what they were doing. As he himself says—and this was true not only for the men of this police battalion but for Germans serving throughout eastern Europe—Jews were axiomatically identified with "bandits" and their anti-German activities. How did this German and his comrades conceive of them? "The category of human being was not applicable ..."40 Another genocidal executioner, a member of one of the mobile police units subordinated to the commander of the Order Police in Lublin, confirms this. His is a candid, confessional sentence that brings out, in sharp relief, the motivational mainspring of the Germans who—uncoerced, willingly, zealously, and with extraordinary brutality—participated in the destruction of European Jewry. Simply put, "The Jew was not acknowledged by us to be a human being."41