16

ELIMINATIONIST ANTISEMITISM AS GENOCIDAL MOTIVATION

THAT THE PERPETRATORS approved of the mass slaughter, that they willingly gave assent to their own participation in the slaughter, is certain. That their approval derived in the main from their own conception of Jews is all but certain, for no other source of motivation can plausibly account for their actions. This means that had they not been antisemites, and antisemites of a particular kind, then they would not have taken part in the extermination, and Hitler's campaign against the Jews would have unfolded substantially differently from how it did. The perpetrators' antisemitism, and hence their motivation to kill, was, furthermore, not derived from some other non-ideational source. It is not an intervening variable, but an independent one. It is not reducible to any other factor.

This, it must be emphasized, is not a monocausal account of the perpetration of the Holocaust. Many factors were necessary for Hitler and others to have conceived the genocidal program, for them to have risen to the position from which they could implement it, for its undertaking to have become a realistic possibility, and for it then to have been carried out. Most of these elements are well understood. This book has focused on one of a number of the causes of the Holocaust, the least well-understood one, namely the crucial motivational element which moved the German men and women, without whom it would and could not have occurred, to devote their bodies, souls, and ingenuity to the enterprise. With regard to the motivational cause of the Holocaust, for the vast majority of perpetrators, a monocausal explanation does suffice.

When focusing on only the motivational cause of the Holocaust, the following can be said. The claim here is that this virulent brand of German racial antisemitism was in this historical instance causally sufficient to provide not only the Nazi leadership in its decision making but also the perpetrators with the requisite motivation to participate willingly in the extermination of the Jews. This does not necessarily mean that some other set of factors (independent of or conjoined with the regnant German antisemitism) could not conceivably have induced Germans to slaughter Jews. It merely means that it simply did not happen.

To be sure, some of the mechanisms specified by the conventional explanations were at work, shaping the actions of some individuals. It cannot be doubted that individual Germans became perpetrators despite a principled disapproval of the extermination. After all, not all perpetrators were offered the opportunity to refuse to kill and not all were serving under a commander as kindly as Police Battalion 101's "Papa" Trapp. It is also likely that disapproving individuals, finding themselves in an atmosphere of general approval, would, because of group pressure, commit acts which they had considered to be crimes, perhaps finding comforting rationalizations to assuage their consciences. It cannot be ruled out that some individuals, who were themselves not beholden to virulent German antisemitism, would have been moved to kill by a cynicism that set the value of some coveted advantage, material or otherwise, higher than that of the lives of innocent people. A presumption of coercion, social psychological pressure from assenting comrades, and the occasional opportunities for personal advancement, in different measures, were at times real enough; yet they cannot explain, for all the reasons already adduced, the actions in all of their varieties of the perpetrators as a class, but only some actions of some individuals who might have killed despite their disapproval, or of others who might have needed but a push to overcome reluctance, whatever its source. Nevertheless, none of these factors influenced the general course of the perpetration of the Holocaust fundamentally. Had these particular non-ideological factors—to the extent that they even existed—not been present, then the Holocaust would still have proceeded apace. And it must be emphasized that for analytical purposes these factors are not very significant; all the ordinary, representative Germans who were not under coercion, who had no career or material advantage to gain from killing, who formed the assenting majority that might have created pressure for dissenting individuals, and who nevertheless killed, all these ordinary, representative Germans show that these non-ideological factors were mainly irrelevant to the perpetration of the Holocaust.1 They show that racial eliminationist antisemitism was a sufficient cause, a sufficiently potent motivator, to lead Germans to kill Jews willingly; absent these other tertiary factors, the perpetrators would have acted more or less as they did—once mobilized by Hitler in this national undertaking.

A second claim is equally strong. Not only was German antisemitism in this historical instance a sufficient cause, but it was also a necessary cause for such broad German participation in the persecution and mass slaughter of Jews, and for Germans to have treated Jews in all the heartless, harsh, and cruel ways that they did. Had ordinary Germans not shared their leadership's eliminationist ideals, then they would have reacted to the ever-intensifying assault on their Jewish countrymen and brethren with at least as much opposition and non-cooperation as they did to their government's attacks on Christianity and to the so-called Euthanasia program. As has already been discussed, especially with regard to religious policies, the Nazis backed down when faced with serious, widespread popular opposition. Had the Nazis been faced with a German populace who saw Jews as ordinary human beings, and German Jews as their brothers and sisters, then it is hard to imagine that the Nazis would have proceeded, or would have been able to proceed, with the extermination of the Jews. If they somehow had been able to go forward, then the probability that the assault would have unfolded as it did, and that Germans would have killed so many Jews, is extremely low. The probability that it would have produced so much German cruelty and exterminatory zeal is zero. A German population roused against the elimination and extermination of the Jews most likely would have stayed the regime's hand.

More generally, it can be said that certain kinds of dehumanizing beliefs2 about people, or the attribution of extreme malevolence to them, are necessary and can be sufficient to induce others to take part in the genocidal slaughter of the dehumanized people, if they are given proper opportunity and coordination, typically by a state.3 Yet such beliefs alone are not on their own always sufficient to produce a genocide, for other inhibiting factors may be operative, such as an ethical code and a moral sensibility which prohibit killing of this sort. Such beliefs constitute the enabling conditions necessary for a state to mobilize large groups of people to take part in genocidal slaughter. A hypothetical exception to the necessary existence of such genocidal beliefs is when coercion on a massive scale might be applied (by the state) to people compelled to become perpetrators. Although this could undoubtedly cause individuals to kill, it seems to me unlikely ever to succeed in making tens of thousands murder hundreds of thousands or millions over a prolonged time. Moreover, as far as I know, it has never happened—not in Cambodia, Turkey, Burundi, Rwanda, or the Soviet Union, to name prominent twentieth-century places of genocide.4 The Nazi leadership, like other genocidal elites, never applied, and most likely would not have been willing to apply, the vast amount of coercion that it would have needed to move tens of thousands of non-antisemitic Germans to kill millions of Jews. The Nazis, knowing that ordinary Germans shared their convictions, had no need to do so.

The Holocaust was a sui generis event that has a historically specific explanation. The explanation specifies the enabling conditions created by the long-incubating, pervasive, virulent, racist, eliminationist antisemitism of German culture, which was mobilized by a criminal regime beholden to an eliminationist, genocidal ideology, and which was given shape and energized by a leader, Hitler, who was adored by the vast majority of the German people, a leader who was known to be committed wholeheartedly to the unfolding, brutal eliminationist program. During the Nazi period, the eliminationist antisemitism provided the motivational source for the German leadership and for rank-and-file Germans to kill the Jews. It also was the motivational source of the other non-killing actions of the perpetrators that were integral to the Holocaust.

It is precisely because antisemitism alone did not produce the Holocaust that it is not essential to establish the differences between antisemitism in Germany and elsewhere.5 Whatever the antisemitic traditions were in other European countries, it was only in Germany that an openly and rabidly antisemitic movement came to power—indeed was elected to power—that was bent upon turning antisemitic fantasy into state-organized genocidal slaughter. This alone ensured that German antisemitism would have qualitatively different consequences from the antisemitisms of other countries, and substantiates the Sonderweg thesis: that Germany developed along a singular path, setting it apart from other western countries. So whatever the extent and intensity of antisemitism was among, say, the Poles or the French, their antisemitism is not important for explaining the Germans' genocide of the Jews; it might help to explain the Polish or French people's reactions to the German genocidal onslaught, but that is not an issue under consideration here.6 Even if, for explanatory purposes, it is not essential to discuss German antisemitism comparatively, it is still worth stating that the antisemitism of no other European country came close to combining all of the following features of German antisemitism (indeed, virtually every other country fell short on each dimension). No other country's antisemitism was at once so widespread as to have been a cultural axiom, was so firmly wedded to racism, had as its foundation such a pernicious image of Jews that deemed them to be a mortal threat to the Volk, and was so deadly in content, producing, even in the nineteenth century, such frequent and explicit calls for the extermination of the Jews, calls which expressed the logic of the racist eliminationist antisemitism that prevailed in Germany. The unmatched volume and the vitriolic and murderous substance of German antisemitic literature of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries alone indicate that German antisemitism was sui generis.

This is a historically specific explanation, yet it has implications for our understanding of other genocides and suggests why a greater number of genocides have not occurred; even though severe conflicts and war have characterized group relations throughout history and today, a genocidal ideology and genocidal opportunities must be simultaneously present if people are to be motivated and able to exterminate other groups of people. The genocidal ideology has generally been absent, and even when it has been present and has motivated people to kill others, the content of the ideology, which always includes an account of the putative nature of the victims, has led other perpetrators to treat their victims in ways that have differed significantly from the comprehensively and singularly brutal deadly German assault upon the Jews.

IT is BECAUSE factors other than exterminationist antisemitism shaped the Germans' actions that the character of the interaction of the various influences, including strategic and material constraints, needs to be understood. This, as was detailed earlier, can be seen at the policy level in the evolution of the Germans' eliminationist policies into exterminationist ones as the opportunities and constraints became more favorable for a "final solution."

Whatever the constancy of Hitler's and other leading Nazis' eliminationist ideals was, the Germans' anti-Jewish intentions and policy had three distinct phases.7 Each was characterized by different practical opportunities for "solving" the "Jewish Problem" that derived—this was true both of the possibilities and the constraints—from Germany's geostrategic situation, namely from its position on the European continent and its relations with other countries.

The first phase lasted from 1933 until the outbreak of the war. The Germans implemented the utterly radical policies of turning the Jews into socially dead beings and of forcing most of them to flee from their homes and country. They did so by perpetrating ceaseless verbal and sporadic yet ferocious physical violence upon Jews, by depriving them of civil and legal protections and rights, and by progressively excluding them from virtually all spheres of social, economic, and cultural life. At a time when most of Europe's Jews were beyond the Germans' reach—rendering a lethal "solution" to the "Jewish Problem" unfeasible—and when a comparatively weak Germany was pursuing dangerous foreign policy goals and arming in preparation for the coming war, these were the most final "solutions" that were practicable, the only ones that they could prudentially adopt.

The second phase lasted from the beginning of the war until early 1941. The conquest of Poland and then of France and the prospective defeat or peace with Britain created new opportunities for the Germans, yet fundamental constraints remained. They now had over two million, not mere hundreds of thousands, of European Jews under their control, so they could entertain some "solution" to the "Jewish Problem" more effective than anything possible while Germany remained confined to its 1939 borders. Yet killing these Jews was still not opportune, because a good part of the putative wellspring of Jewry remained out of reach in the Soviet Union, and because the uneasy non-aggression pact with the "Jewish-Bolshevik" Soviet Union could have been expected to disintegrate prematurely, to the detriment of the Germans, should they then have begun the genocidal killing of Jews under the gaze of the Soviet troops stationed in the heart of Poland. Still, during this period the Germans fashioned more apocalyptic plans and began to implement them. By the beginning of this phase, the Germans had made it clear that the Jews' lives were worthless and forfeit; that anything, literally anything, could be done to them. The Germans proceeded to sever the Jews from the economy of German-occupied Poland, to ghettoize them under inhuman, deadly conditions, which produced starvation and a high mortality rate. All Jews were "vogelfrei," outlaws who were fair game. Germans could and did kill Jews at a whim. The groundwork had clearly already been laid for the Germans to exterminate them or to devise some surrogate quasi-genocidal fate for them.

Under these more propitious circumstances, the Nazis contemplated more radical "solutions"—bloodless equivalents of genocide. They began to explore the possibility of removing this good portion of all of European Jewry living under their dominion to some god-forsaken territory, where they could discard, immure, and leave the Jews to wither and expire. In November 1939, at a meeting devoted to expulsions, Hans Frank, the German Governor of Poland, expressed the underlying exterminationist motive that was already operative in and constitutive of the relocation schemes: "... We won't waste much more time on the Jews. It's great to get to grips with the Jewish race at last. The more that die the better."8 During this second phase, the Germans pursued the most radical "solutions" that were practicable and prudent. Their proto-genocidal policies for handling Jews within their dominion gave a new lethality to their Jewish policies. Their bloodlessly genocidal eliminationist "solution" of vast deportations, however, did prove to be chimerical— the only major German initiative against the Jews that did—but to no great disappointment on the part of the Nazi leadership, for the impending conquest of the Soviet Union rendered such deportations undesirable, by offering them at last the opportunity for a truly final and irrevocable "solution."

The third phase began with the planning of the attack on the Soviet Union and the invasion itself. It was only during this phase that killing the Jews whom the Germans could actually reach would prove to be, from their hallucinatory perspective, an effective and not a counterproductive policy. It was only then that a "final solution" by systematic killing was practical. It was only then that the Germans no longer had major political and military constraints hindering them from pursuing such a policy. It is no surprise, therefore, that immediately upon launching the assault on the Soviet Union, Germans began to implement Hitler's decision, already cast, to exterminate all of European Jewry. During this phase, with the exception of some tactical attempts to use Jews to gain concessions from the Allies, every German measure affecting the Jews either led to their immediate deaths, was a means that would hasten or contribute eventually to their deaths, or was a temporary surrogate for death.9 With the absence of any but comparatively minor logistical constraints upon their eliminationist desires, the eliminationist compulsion in the form of the slaughter of the Jews came to take priority over every other goal. The Germans continued with it in the form of mass shootings and death marches until, literally, the final day of the war.

Most striking about the Germans' anti-Jewish policy is that in each of the three phases, its major thrust was the maximum feasible eliminationist option possible given the existing opportunities and constraints. There was no unintended cumulative radicalization of policy because of bureaucratic politics or for any other reason.10 The extent and virulence of the verbal violence assaulting the Jews from their own countrymen have no parallel in modern history. The rapid enactment of discriminating, debilitating, and dehumanizing legislation also has no parallel in modern history. The speed with which this group of prosperous, economically and culturally relatively well-integrated citizens were stripped of their rights and, with the approval of the vast majority of people in their society, turned into social lepers has no parallel in modern history. Our knowledge of the genocidal measures that followed tends to obscure how radical the Germans' treatment of Jews was during the 1930s. All of these measures, the turning of Jews into socially dead beings, and the policies that sought to compel them, 500,000 people, to emigrate from Germany constituted an utterly "radical" campaign, the likes of which western Europe had not seen for centuries. Those who argue that a radicalization of German policy towards the Jews occurred only in the 1940s minimize the radical nature of the anti-Jewish policy of the 1930s (which was noted as such by contemporaries) and miss the underlying continuity among the three phases of the anti-Jewish policy.

Indeed, the Germans' anti-Jewish policy evolved in a logical manner— always flowing from the eliminationist ideology—in consonance with the creation of new eliminationist opportunities, opportunities which Hitler was happy to exploit, promptly and eagerly, to their limits. Holding Hitler back in the first two phases were the practical limits on policy, limits imposed by Germany's constrained capacity to "solve" the "Jewish Problem"—independent of any other considerations—and by the existence of other considerations, the prudential ones regarding Germany's military and geo-political situation." On October 25, 1941, a few months after Hitler's genocidal onslaught had begun, Hitler reminded Himmler and Heydrich—during a long disquisition that began with a reference to his January 1939 prophecy that the war would end with the elimination of the Jews—of what they already knew: that, having often operated under severe constraints, he had been content to wait for the right moment to pursue his apocalyptic ideals: "I am compelled to accumulate within me a tremendous amount; that does not, however, mean that what I take note of, but to which I do not react immediately, becomes extinguished in me. It is entered into a ledger; one day the book is brought out. Vis-à-vis the Jews as well, I had to remain for long inactive. It is pointless artificially to cause oneself additional difficulties; the cleverer one proceeds, the better."12 Hitler was presenting himself as the prudent politician that he often was, biding his time, waiting for a propitious moment to strike. He had for long been "inactive" with regard to the Jews. The word "inactive" (tatenlos) here could have meant only "abstinence from mass killing," since for eight years Hitler had been very active indeed against the Jews, persecuting them, degrading them, burning their synagogues, expelling them from Germany, herding them into ghettos, and even killing them sporadically. For him, all these measures had amounted to inaction, for they all fell short of the one act that was adequate to the necessary task, adequate to the threat. The patiently longed-for final act that, for Hitler, qualified as real "action" was the physical annihilation of the Jews.13

In no sense was Hitler's monumental, indeed world-historical, decision—driven as it was by his fervent hatred of Jews—to exterminate European Jewry an historical accident, as some have argued, that took place because other options were closed off to him or because of something as ephemeral as Hitler's moods. Killing was not undertaken by Hitler reluctantly. Killing, biological purgation, was for Hitler a natural, preferred method of solving problems. Indeed, killing was Hitler's reflex. He slaughtered those in his own movement whom he saw as a challenge. He killed his political enemies. He killed Germany's mentally ill. Already in 1929, he publicly toyed with the idea of killing all German children born with physical defects, which he numbered in a murderously megalomaniacal moment of fantasy at 700,000 to 800,000 a year.'4 Surely, death was the most fitting penalty for the Jews. A demonic nation deserves nothing less than death.

Indeed, it is hard to imagine Hitler and the German leadership having settled for any other "solution" once they attacked the Soviet Union. The argument that only circumstances of one sort or another created Hitler's and the Germans' motive to opt for a genocidal "solution" ignores, for no good reason, Hitler's oft-stated and self-understood intention to exterminate the Jews. This argument also implies, counterfactually, that had these putative motivation-engendering circumstances not been brought about—had Hitler's allegedly volatile moods not allegedly swung, had the Germans been able to "resettle" millions of Jews—then Hitler and the others would have preferred some other "solution" and then millions of additional Jews would have survived the war. This counterfactual reasoning is highly implausible.15 It would have necessitated that during this Vernichtungskrieg, this avowed war of total destruction, some circumstances would have led the Germans to spare their "anti-Christ," the Jews, even though Hitler and Himmler were planning to dispossess and kill millions of, in their view, the far less threatening Slavs (before the attack on the Soviet Union, Himmler once set the expected body count for that country at thirty million), when creating the planned "Germanic Eden" of eastern Europe.16

Hitler, on January 25, 1942, after affirming that "the absolute extermination" of the Jews was the appropriate policy, himself pointed out to Himmler, the head of his Chancery, Hans Lammers, and General Kurt Zeitzler how nonsensical it would have been not to be killing the Jews: "Why should I look upon a Jew with eyes other than [if he were] a Russian prisoner [of war]? In the POW camps many are dying, because we have been driven by the Jews into this situation. What can I do about it? Why did the Jews instigate this war?"17 In addition to the general implausibility of the counterfactual notion that Hitler and Himmler preferred or would have preferred a non-genocidal course once they had unleashed their forces against the Soviet Union, the facts do not support such speculative reasoning. Once the extermination program began, the Germans conceiving and implementing the mass slaughter did not consider any other "solution" to be preferable;18 they did not lament that the "Jewish Problem" could not be solved through emigration or "resettlement." All indications suggest that they understood the genocidal slaughter as the natural and therefore appropriate means to dispose of the Jews now that such an option had become practicable.

The idea that death and death alone is the only fitting punishment for Jews was publicly articulated by Hitler at the beginning of his political career on August 13, 1920, in a speech entirely devoted to antisemitism, "Why Are We Antisemites?" In the middle of that speech, the still politically obscure Hitler suddenly digressed to the subject of the death sentence and why it ought to be applied to the Jews. Healthy elements of a nation, he declared, know that "criminals guilty of crimes against the nation, i.e., parasites on the national community," cannot be tolerated, that under certain circumstances they must be punished only with death, since imprisonment lacks the quality of irrevocableness. "The heaviest bolt is not heavy enough and the securest prison is not secure enough that a few million could not in the end open it. Only one bolt cannot be opened—and that is death [my emphasis]."19 This was not a casual utterance, but reflected an idea and resolve that had already ripened and taken root in Hitler's mind.

In the discussion that ensued with members of the audience about the above-mentioned speech, Hitler revealed that he had contemplated the question of how the "Jewish Problem" is to be solved. He resolved to be thoroughgoing. "We have, however, decided that we shall not come with ifs, ands, or buts, but when the matter comes to a solution, it will be done thoroughly." 20 In the speech proper, Hitler spelled out, with a candid explicitness that he prudently would not repeat in public after he had achieved national prominence, what he meant by the phrase "it will be done thoroughly." It meant that putting the entire Jewish nation to death—or, as Hitler himself had stated publicly a few months earlier in another speech, "to seize the Evil [the Jews] by the roots and to exterminate it root and branch"—would be the most just and effective punishment, the only enduring "solution." Mere imprisonment would be too clement a penalty for such world-historical criminals and one, moreover, fraught with danger, since the Jews could one day emerge from their prisons and resume their evil ways. Hitler's maniacal conception of the Jews, his consuming hatred of them, and his natural murderous propensity rendered him incapable of becoming reconciled permanently to any "solution of the Jewish Problem" save that of extinction.

The road to Auschwitz was not twisted. Conceived by Hitler's apocalyptically bent mind as an urgent, though future, project, its completion had to wait until conditions were right. The instant that they were, Hitler commissioned his architects, Himmler and Heydrich, to work from his vague blueprint in designing and engineering the road. They, in turn, easily enlisted ordinary Germans by the tens of thousands, who built and paved it with an immense dedication born of great hatred for the Jews whom they drove down that road. When the road's construction was completed, Hitler, the architects, and their willing helpers looked upon it not as an undesirable construction, but with satisfaction. In no sense did they regard it as a road chosen only because other, preferable venues had proven to be dead ends. They held it to be the best, safest, and speediest of all possible roads, the only one that led to a destination from which the satanic Jews are absolutely sure never to return.

THE INTERACTION of a variety of influences on the Germans' treatment of Jews on all institutional levels can be seen also, in a manner still more complex than in the evolution of the Germans' general eliminationist assault on the Jews, in the realm of Jewish "work." In the area of Jewish "work," as with the anti-Jewish policy, despite enormous material obstacles and constraints (in this case, urgent economic need), the power of German eliminationist antisemitism was the force that drove the Germans to override other considerations, even if the pattern of German actions that emerged at first seems hard to fathom.

There can be no doubt that the objective economic needs were the principal cause of Germans putting Jews to work. But the rational need did not produce anything resembling a rational German response, and the two should not be confused. The need could be translated into labor only in a distorted, atrophied way, because it came into conflict with far more powerful ideological dictates. The creation of a special Jewish economy, which was by and large separated from the general economy, produced an enormous drop in overall Jewish productivity and did substantial damage to the economic health of war-engulfed Germany. The Lublin camps are particularly noteworthy because they existed in a context of the Germans' general work mobilization of continental Europe, and after orders had been given by Himmler to treat non-German workers better. They show that the ideological foundations of Germany during the Nazi period rendered it constitutionally incapable of creating the conditions for the decent treatment and the rational use of Jewish labor power. Because of the Germans' fantastical beliefs about Jewish evil, the Jews had to be segregated, had to be removed from the general economy, in which they should have been integrated had the Germans wanted to utilize their talents, skills, and labor in an economically rational manner. The policies that brought millions of other laborers to Germany, both people from the West and "subhumans" from the East, and that led to over thirty thousand of them fleeing their German masters every month in 1943,21 could not have been duplicated for Jews. Any policy which held out at this time the mere possibility, however unintended, of large numbers of Jews roaming around the countryside unchecked was unimaginable in Germany. The Jews had to be incarcerated in the only places deemed fitting, in leper-like colonies where disease and death festered. This produced even more deleterious economic results. And this Jewish economy was itself absolutely irrationally organized and run, and woefully unproductive. In war-ravaged Europe, the Germans found it difficult to bring to these bizarre and eerie colonies on the figurative frontier of humanity the plant, equipment, and conditions of work that were necessary for any rational kind of production to occur. Furthermore, it was itself destroyed in large chunks at a time when the Germans decided, for extra-economic reasons, to kill some group or community of Jews. The realm of politics and the realm of social relations, in this matter, worked hand in glove towards the same end. The political-ideological imperative to separate the Jews from Germans, to punish the Jews, and to kill them, together with the manifold forms of crippling and fatal abuse to which the Jews' "foremen" subjected their "workers" in face-to-face relations, prevented the Germans from meeting their pressing economic needs. The objective economic need existed. The Germans were ideologically and psychologically unfit to respond to it. If the Germans had used all the Jews as slaves, which they could easily have done, then they would have extracted great economic profit from them. But they did not do so. They were like slave masters who, driven by frenzied delusions, murdered most of their slaves and treated the small percentage whom they did put to work so recklessly and cruelly that they crippled the slaves' capacity for work.

Economic irrationality and cruelty and debilitation were embedded in the organizational, material, and psychological constitution of the German institutions (including the overseers) of Jewish "work." It is not just, as others have correctly maintained, that extermination had political priority over economics and work, as if the leadership had willfully made a choice between alternative possibilities.22 During its Nazi period, Germany developed along a path, according to the logic of its animating beliefs, that made it, probably by 1941 and certainly by 1943, generally incapable of the rational economic use of Jews, except, at times, on a local basis. The Germans were so beholden to the barbarous implications of their ideology that even when they tried to apply the normal linguistic and practical forms of work to Jews, they generally failed, except in crippled and crippling approximations. The power of German antisemitism to derail rationality in the economy, the realm of modern industrial society where rationality is most consistently sought, and which for non-Jews was highly rationally organized, demonstrates that with regard to the Jews, the Germans' ideology had created for them a cognitive map singular in nature, leading them in directions that they themselves would have considered false and dangerous-at odds with reality and rationality— for peoples other than Jews.23

Just as antisemitism operated in conjunction with other factors on the levels of policy and of institutional practice, so too did it at times on the individual level. On the individual level, it is clear that although German antisemitism was sufficient to motivate the perpetrators, it did not produce completely uniform practices. Other factors of belief and personality naturally gave variation to individual action. The degree of enthusiasm that Germans brought to their dealings with Jews as well as the cruelty that they showed did vary, undoubtedly because of the perpetrators' different degrees of inhibitions, their characters, and, especially in the case of cruelty, their taste for barbarism, the pleasure that they took in the suffering of Jews, their sadism. The norm in Police Battalion 101 was that the men carried out their eliminationist tasks willingly and skillfully, yet, as one of the battalion's lieutenants, fully aware of the base-line exemplary performance of his compatriots, says, there were men "who particularly distinguished themselves on missions. This was true in this respect also for Jewish actions."24 Even by the high standard that the genocidal cohort that was Police Battalion 101 set, some, indeed many, of the men distinguished themselves. Similarly, virtually all Germans in concentration camps brutalized Jews. That was the common feature. Some brutalized Jews more frequently, vigorously, or inventively than others. That was the variance which, in light of the Holocaust's constituent feature of near universal cruelty, is really but a nuance of action in need of explanation. It is also no surprise that a small number of people refrained from killing or brutalizing Jews. In Germany, some people dissented from the prevailing Nazified conception of Jews, and others, even if they shared this view, still adhered to a restraining ethical standard at odds with the disinhibiting one of the new dispensation. Minority cognitions of these sorts gave such people, but a tiny percentage of Germans, the impetus to help hide Jews in Germany25 and, in the killing fields, made such people unwilling to take part in the genocide. The existing opportunities to avoid killing permitted these same people to realize their wishes. Hence the small group of refusers.

THE VIRULENT, racial antisemitism, in motivating Germans to push the eliminationist program forward on the macro, meso, and micro levels, must be understood to have been moving people who were operating under constraints, both external ones and those created by competing goals. This was true of Hitler and of the lowliest guard in a "work" camp. These ameliorating circumstances notwithstanding, the eliminationist antisemitism was powerful enough to have set Hitler and the German nation on an exterminationist course, powerful enough to have overridden economic rationality so thoroughly, powerful enough to have produced in so many people such individual voluntarism, zeal, and cruelty. The eliminationist antisemitism, with its hurricane-force potential, resided ultimately in the heart of German political culture, in German society itself.

Because the "Jewish Problem" was openly assigned high political priority and discussed continuously in the public sphere, there can be no doubt that the German people understood the purpose and the radicality of the anti-Jewish measures unfolding before their eyes during the 1930s. How could they not? "Jews are our misfortune"26 was shouted from every rooftop in Germany. "Jew perish," no mere hyperbolic metaphorical flourish, could be heard and seen around Germany in the 1930s.

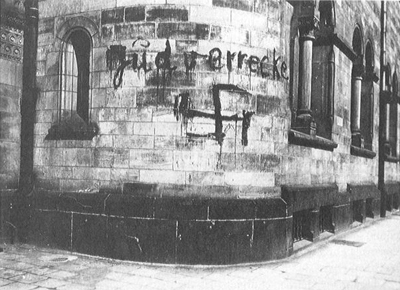

In Düsseldorf, an execration painted on the wall of a synagogue: "Jew perish"

The perpetrators, from Hitler to the lowliest officials, were openly proud of their actions, of their achievements; during the 1930s, they proclaimed and carried them out in full view and with the general approval of the Volk.

If ordinary Germans did not concur with Melita Maschmann's Nazified conception of Jews as a corporate "active force for evil" whose "wickedness was directed against the prosperity, unity and prestige of the German nation," if Germans did not share her abhorrence and demonology of Jews, then what did they believe? Did they believe that Jews were ordinary human beings, but simply of another religion? Did they believe perhaps that Jews harbored some objectionable qualities, but nothing remotely resembling the perniciousness that the beloved Hitler and the Nazis, as an article of faith, incessantly and emphatically attributed to them? Did they identify with the Jews as innocent victims of a deluded regime? Did they see all of the groups and numerous people in German society who aided the persecution as being deluded? If Germans had dissented from Hitler's conception of Jews, from the characterization of Jews as a powerful evil that is racially destined to harm and destroy the German Volk, if Germans had been moved by some other more benevolent conception of Jews, then what is the evidence for it? The Gestapo and its informers pursued people who expressed their divergence from Nazi antisemitism with a zeal that has led the foremost expert on the Gestapo to conclude that all such cases were reported and investigated. Yet in all of Lower Franconia, a region with 840,663 people (in 1939)—a region in which, as in all regions of Germany, Germans expressed an enormous amount of dissent on a broad range of Nazi policies, including on the treatment of foreigners— during twelve years of Nazi rule, only fifty-two such cases, four per year, came to the attention of the Gestapo! In the still much larger jurisdiction of Munich between 1933 and 1944, only seventy people were tried for remarks critical of the eliminationist project. The number of remarks was so small as to have been "almost insignificant."27

At no point during the Nazi period did significant portions, or even identifiable minorities, of the German people express either dissent from the dominant elaboration of the nature of Jews or principled disapproval of the eliminationist goals and measures that the German government and so many Germans pursued. After the war, many Germans and many scholars have asserted otherwise, but have provided little real evidence to support their claims.

How many German churchmen in the 1930s did not believe that the Jews were pernicious? Where is the evidence to support the contention that a significant number of them rejected the eliminationist antisemitic view of Jews?

How many German generals, the supposed guardians of traditional German honor and moral rectitude, did not want to cleanse Germany of Jews? Himmler, in fact, once discussed the extermination of the Jews in a speech before a good portion of the leadership of the armed forces—three hundred generals and staff officers gathered in Posen on January 25, 1944. The genocide was hardly news to the military leaders for, by then, the Germans had killed millions of Jews, and the army had been a full partner in the slaughter of Soviet Jewry. Himmler, knowing the army leadership well—which, as the abundant and irrefutable evidence shows, was in "fundamental agreement" with the extermination of the Jews28—spoke openly as someone does before an approving crowd. Indeed, when Himmler announced that Germany was wiping the Jews off the face of the earth, the military leaders broke into applause. The applause was not scattered; it was well-nigh unanimous. A dissenting general looked about him to see how many in the audience abstained from applauding. He counted five.29

What is the evidence for the belief that these men and their brethren saw the Jews as fellow Germans deserving full rights? Even many of those who hated the Nazis and plotted to kill Hitler were eliminationist antisemites.

How many jurists, how many in the medical community, how many in other professions held the ubiquitous, public antisemitism, with its hallucinatory elements, to be sheer nonsense? Where is the evidence?

How many of the over eight million members of the Nazi Party, and how many other ordinary Germans thought that Hitler's obsessive antisemitism were the ravings of a madman—and therefore that Hitler was a madman— that the eliminationist measures and the societal attack upon Jews of the 1930s were criminal, that all those measures ought to have been reversed and the Jews restored to their prior places in German society? Where is the evidence?

To be sure, not all churchmen, generals, jurists, and others wanted to exterminate the Jews. Some wanted to deport them, a few wanted to sterilize them, and some would have been content to deprive the Jews "only" of fundamental rights. Nevertheless, underlying all of these views was an eliminationist ideal. Where is the evidence for any other conclusion?

The words of one man, Pastor Walter Höchstädter, who in the summer of 1944 was a hospital chaplain in France, cast into sharp relief the powerful hold that the antisemitic cognitive model had on the rest of Germany, even typically on those who opposed aspects of the eliminationist program. Höchstädter secretly printed his indicting protest and sent one thousand copies through the military mail to soldiers at the front:

We live in an age which is raging throughout with mad ideas and demons, no less than the Middle Ages. Our allegedly "enlightened" age, instead of indulging in an orgy of crazed witch-hunting, feasts itself in an orgy of maniacal Jew-hatred. Today the Jew-hating madness, which had already raged frightfully in the Middle Ages, has entered upon its acute stage. This, the Church, the community of Jesus Christ, must acknowledge. If she does not do it, then she will have failed, just as she had failed then, during the time of the witch-hunts. Today, the blood of millions of slaughtered Jews, of men, women, and children, cries to heaven. The Church is not permitted to be silent. She is not permitted to say that the settlement of the Jewish Problem is a matter for the state, the right to perform this function having been granted to it by Romans 13. The Church is also not permitted to say that in our time just punishment is being carried out upon the Jews for their sins.... There is no such thing as a moderate Christian antisemitism. Even when it is set forth seemingly convincingly by means of reasonable arguments (say, national ones) or even with scientific (read pseudo-scientific) arguments. The witch craze also was once scientifically justified by leading authorities of the theological, legal, and medical faculties. The battle against Jewry proceeds from the same muddy source from which the witch craze once proceeded. Contemporary mankind has not overcome its proclivity to look for a "scapegoat." Therefore it searches for all kinds of guilty parties—the Jews, the Freemasons and supra-state powers. This is the background of the hymns of hate of our time.

... Who gives us the right to lay the blame solely on the Jews? A Christian is forbidden to do this. A Christian is not allowed to be an antisemite, and he is not allowed to be a moderate antisemite. The objection that, without the [defensive] reaction of "moderate" antisemitism, the Jewification of the life of the Volk [Verjudung des Volkslebens] would become a horrible danger originates from an unbelieving and purely secular outlook, which Christians ought to overcome.

... The Church ought to live of love. Woe to her if she does not do that! Woe to her if by her silence and by all sorts of dubious excuses she becomes jointly guilty of the world's outbursts of hatred! Woe to her if she adopts words and slogans that originate in the sphere of hatred ...30

In the annals of the history of Germany during its Nazi period, Höchstädter's letter, in its explicit and thoroughgoing rejection of the eliminationist antisemitic model, is an exceedingly rare and luminous document. Nearly all of the few protests and petitions of Germans that lamented or objected to their nation's treatment of the Jews were themselves imbued with antisemitism, an antisemitism that was irrational in its beliefs and harsh in its practical proposals, yet which can seem moderate when compared with the lethal variety practiced by the Nazis and by all of the ordinary Germans who aided them. Virtually all objectors to the physical violence that Germans inflicted on Jews assumed as a matter of course that a "Jewish Problem" did indeed exist, that the Jews were an evildoing tribe that had harmed Germany, and that a "solution" must be found whereby their corrosive presence would be greatly reduced and their influence eliminated. Such "dissenters" still wanted a "solution," one that was "civilized," bloodless, and orderly, not violent and cruel, as was the one that the Nazis had adopted. They wanted to curtail the putative power of the Jews, to exclude them from many spheres of social life, to prohibit them from holding public office, and to impose other restrictions that would render them powerless to harm Germans. Antisemitism ought to be "decent," "moderate," "spiritual," "ethical," "salutary," as befits a civilized nation. The Bishop of Linz, Johannes Maria Gfoellner, in a pastoral letter circulated in 1933, exhorted the Nazis thus: "If National Socialism ... wants to incorporate only this spiritual and ethical form of antisemitism into its program, there is nothing to stop it."31 "Be decent, moderate, spiritual, ethical antisemites, eliminate the Jews, but do not slaughter them" was the spoken or unspoken maxim that informed nearly all of the relatively few German objections to the countrymen's systematic slaughter of the Jews.

The obscure Pastor Höchstädter was dismayed by this brand of "moderation." To him, the Germans' persecution of the Jews sprang from the same troubled mental source from which the medieval witch craze had sprung. The accusations which Germans inside and outside the Church leveled at the Jews were hallucinatory delusions. Höchstädter emphatically rejects the view that existed in the churches and in anti-Nazi circles that what is needed is a "moderate" and "salutary" antisemitism. Antisemitism in any form, he states with a simplicity and clarity that was all but singular during the Nazi period, is a radical evil, a tissue of vicious falsehoods. Therein lies the extreme rarity of Höchstädter's appeal. I know of very few statements by opponents of the Nazis that condemned the wild antisemitic beliefs which were ubiquitous in Germany as wholly false, as devoid of essential truth, as frenzied, monstrous obsessions, in the manner that Höchstädter did in his anguished letter. He calls upon the clergy to come to their senses, to awaken from their delusions, to break their silence in the face of the millionfold slaughter of the Jews. "Therefore Be Sober" reads the admonition with which Höchstädter entitled his appeal.

How singularly sober, how "abnormal," how forlorn Höchstädter's cri de coeur appears when set beside the antisemitic utterances of bishops, ecclesiastical leaders, and other renowned members of the Church—when set beside the statement of Martin Niemöller, the celebrated anti-Nazi clergyman, that the Jews poison everything that they take up; beside Bishop Dibelius' recorded hope that the Jewish community, with its low birth rate, would die out and thus free Germany of its injurious presence; beside Bishop Wurm's assurance that he does not dispute with "a single word" the right of the state to combat Jewry as a dangerous element which corrodes "the religious, moral, literary, economic, and political spheres;"32 beside Bishop August Marahrens' statement (made after the war in August 1945 in the course of his confession of guilt for not having spoken up for the Jews) that although a number of them had brought "a great disaster" (ein schweres Unheil) upon the German people, the Jews should not have been attacked in so "inhumane a manner."33 So besotted were he and all those who shared his sort of "ethical" antisemitism that even after the war the good bishop appeared to imply that a more humane castigation would have been sufficient. Particularly glaring is the contrast between Höchstädter's appeal and the collective declaration of the National Church leaders of the Evangelical churches of Mecklenburg, Thuringia, Saxony, Nassau-Hesse, Schleswig-Holstein, Anhalt, and Lübeck urging that all Jewish converts to Christianity be expelled from the Church, that the "severest measures against the Jews be adopted," and that "they be banished from German lands."34 Given the Germans' full-scale slaughter of Soviet Jews that was already under way, this proclamation is a unique document in the history of Christendom—an ecclesiastical imprimatur of genocide. Even if these leading men of God had not known that the deportees were destined to be slaughtered (which is highly unlikely since knowledge of the mass killings was already enormously widespread, including among other Church leaders), their proclamation would still be a rare and perhaps unique document in the modern history of the Christian churches—an ecclesiastical appeal to a tyrannous, enormously brutal state to treat an entire people with even greater brutality, to proceed against that people without any mitigation. For the churchmen were not only acquiescing in the persecution of the Jews; they were, on their own initiative, urging their government to adopt not merely "severe measures" but the "severest measures," by which they could have meant only measures even more severe than those to which the Jews had hitherto been subjected, measures which were bound to deepen the Jews' degradation and increase their suffering. The corporate voice of a significant part of the Protestant Church leadership of Germany was scarcely distinguishable from that of the Nazis. It was no doubt ecclesiastical sentiments such as these that Höchstädter had in mind when he included in his appeal the warning sentence "Woe to her [to the Church] if she adopts words and slogans that originate in the sphere of hatred."35

In the eyes of posterity, contemplating the darkness that was Germany during the Nazi period, Höchstädter's letter, recalling The Merchant of Venice, shines forth like a bright beam: "How far that little candle throws his beams! / So shines a good deed in a naughty world."36 But in the vast antisemitic darkness that had descended upon Germany, enveloping even the churches, the appeal of Höchstädter was like a tiny, brief flame of reason and humanity, kindled in secret in a remote corner of occupied France, flickering invisibly.

The loneliness of Höchstädter's principled dissent indicates how important it is for us to focus on the Christian churches when trying to understand the nature of antisemitism in Germany during the Nazi period. The churches and the clergy of which they were composed are particularly instructive on this issue because they composed a large network of non-Nazi institutions, and because a large body of evidence has been preserved about their stance towards Jews during the Germans' persecution and slaughter of them. Moreover, Christianity's moral doctrines and complex traditions regarding Jews make this evidence particularly illuminating and telling.

The Christian churches have borne an ancient animus against Jews, regarding them as a guilt-laden people who not only rejected the divinity of Jesus but also crucified him. The churches were also institutions that believed themselves to be bound by a divine ordinance to preach and practice compassion, to foster love, to relieve suffering, and to condemn crime, wanton cruelty, and mass murder. For all these reasons, the attitude of the churches serves as a crucial test case for evaluating the ubiquity and depth of eliminationist antisemitism in Germany. If the ecclesiastical men, whose vocation was to preach love and to be the custodians of compassion, pity, and morality, acquiesced or looked with favor upon and supported the elimination of the Jews from German society, then this would be further and particularly persuasive proof of the ubiquity of eliminationist antisemitism in German society, an antisemitism so strong that it not only inhibited the natural flow of the feeling of pity but also overruled the moral imperatives of the creed to speak out on behalf of those who have fallen among murderers. As studies of the churches have shown, it cannot be doubted that antisemitism did succeed in turning the Christian community—its leaders, its clergy, and its rank and file—against its most fundamental traditions. The foremost historian of the German Protestant Church during this period, Wolfgang Gerlach, entitled his book When the Witnesses Were Silent. Similarly, Guenther Lewy ends his treatment of the German Catholic Church and the "Jewish Problem," whose leadership's attitudes towards the eliminationist enterprise were only somewhat more critical than that of the Protestant leadership, by quoting the question posed by the young girl to her priest in Max Frisch's Andorra: "Where were you, Father Benedict, when they took away our brother like a beast to the slaughter, like a beast to the slaughter, where were you?" 37

The churches welcomed the Nazis' ascendancy to power, for they were deeply conservative institutions which, like most other German conservative bodies and associations, expected the Nazis to deliver Germany from what they deemed to have been the spiritual and political mire that was the Weimar Republic, with its libertine culture, democratic "disorder," its powerful Socialist and Communist parties which preached atheism and which threatened to rob the churches of their power and influence. The churches expected that the Nazis would establish an authoritarian regime that would reclaim the wrongly dishonored virtues of unquestioning obedience and submission to authority, restore the cultivation of traditional moral values, and enforce adherence to them. The Nazi Party was, to be sure, not wholly faultless in the eyes of the Christians. Indeed, it exhibited disquieting tendencies. Some of its ideologues were manifestly anti-Christian. Others urged a nebulous version of Teutonic paganism. And the Party's support of Christianity embodied in its program was framed in vague, puzzlingly qualified terms. These unwholesome facets of the Nazis the churches tended to interpret with the sort of wishful optimism that was to be found among many people who welcomed Nazism while disliking certain of its aspects—as transient excrescences upon the body of the Party which Hitler, in his wisdom and benevolence towards religion, would slough off as so many alien accretions.

The Nazis' ferocious antisemitism was not a feature of their movement to which the churches objected. On the contrary, they appreciated it, for they too were antisemitic. They too believed in the necessity of curtailing and eliminating the putative power of the Jews. For decades, nearly all the opinions, utterances, and pronouncements about Jews issuing from German ecclesiastical organs or clergymen of all ranks were informed by a deep hostility to Jews. The hostility was for the most part extra-religious, secular in character—an echo of the temporal enmity to Jews that coursed through German society. It did not spring merely from theological sources; it was not merely a latter-day reiteration of the perennial and deep-rooted Christian condemnation of the Jews as a "reprehensible people," as the crucifiers of Jesus, and as the stiff-necked spurners of the Christian revelation. Conjoined with that ancient accusation, and greatly overshadowing it, was the modern indictment of the Jews as the principal driving force behind the relentless tide of modernity that was steadily eroding hallowed and time-honored values and traditions. They held the Jews to be promoters of mammonism, of "soulless capitalism," of materialism, of liberalism, and, above all, of that skeptical and iconoclastic temper that was seen as the bane of the age. Reflecting the current trend of secular antisemitism, the "modern" Christian denigrators of Jews preached that the wickedness of the Jews derives not from their religion, but from their racial instincts, from immutable inborn destructive drives which cause them to act like cankerous weeds in blossoming gardens. Thus, even in the Christian churches, racist antisemitism overlay and, to a large extent, replaced the traditional religious enmity to Jews; the denunciations of the Jews that Christian clergymen broadcasted had become scarcely distinguishable from the diatribes that the militantly secular, racist antisemites delivered. This was especially the case in Protestant Church circles, where such antisemitic opinions were rampant. One Protestant Church organ bearing, with unintended irony, the name "Life and Light" would, in the words of a contemporary observer, "again and again describe the Jews with great zeal as a foreign body of which the German people must rid itself, as a dangerous adversary against whom one must wage a struggle to the last extreme."38 Even a pastor who urged moderation in speaking of and treating the Jews nevertheless concurred in the common belief that they were a deadly affliction. "It is indisputable: the Jews have become for us a national plague which we must ward off." 39

Indeed, the "indisputable" was seldom disputed. These antisemitic sentiments were not confined to a minority within the Protestant churches; they were well-nigh universal. Dissent was rare. To question them took intellectual courage. Who would dare to appear in the frowned-upon role of a defender of that detestable Jewish race whose maleficent character was held to be a self-evident truth? One churchman recalls in his memoirs that antisemitism was so widespread in clerical circles that "explicit objection [to antisemitism] could not be ventured."40

Throughout the period of Nazi rule, as the government and people of Germany were subjecting the Jews of Germany and those of the conquered countries to an increasingly severe persecution that culminated in their physical annihilation, the German Protestant and Catholic churches, their governing bodies, their bishops, and most of their theologians watched the suffering that Germans inflicted on the Jews in silence. No explicit public word of sympathy for the Jews, no explicit public condemnation or protest against their persecution issued from any of the authoritative figures within the churches or from any of their ecclesiastical offices. Only a few lowly pastors and priests spoke out or, rather, cried out forlornly their sympathy with the Jews and, with it, their bitter reproach of the Church authorities for their silence. Of all the Protestant bishops of Germany, one (Bishop Wurm), in a confidential letter to Hitler, protested the slaughter of the Jews. The other bishops were almost as impassive in private as they were in public, and at least one (Martin Sasse of Thuringia) published a pamphlet, bristling with virulent antisemitism, that explicitly justified the burning of the synagogues and large scale anti-Jewish violence.

In sum, in the face of the persecution and annihilation of the Jews, the churches, Protestant and Catholic, as corporate bodies exhibited an apparent, striking impassiveness. Moreover, in the ranks of the clergy at all levels, numerous voices could be heard vilifying the Jews in Nazi-like terms, hurling imprecations at them, and acclaiming their persecution at the hands of their country's government. No serious historian would dispute the anti-Nazi theologian Karl Barth's verdict contained in his parting letter before leaving Germany in 1935: "For the millions that suffer unjustly, the Confessing Church does not yet have a heart."41 To which it could be added, "and would not exhibit a heart during the entire Nazi era."

The impassiveness of the Protestant and Catholic churches, their official public silence is thrown into particularly sharp relief by the very few, scattered, impassioned, yet barely audible and utterly ineffectual voices of reproach and protest that were raised within their precincts by lowly isolated figures. Perhaps the most impassioned, the bluntest, the most detailed and most damning of the protests against the silence of the Christian churches came from the pen of a comparatively obscure officer of one of its auxiliary organizations, the chair of the Evangelical Welfare Service of the Berlin-Zehlendorf district, Marga Meusel. It consisted of a lengthy memorandum prepared for the synod of the Protestant Confessing Church which met at Steglitz between September 26 and 29, 1935. Meusel supplemented the memorandum with additions which she completed on May 8, 1936. She had been prompted to make these additions by the worsening plight of the Jews that resulted from the Nuremberg Laws. The memorandum vividly describes the manner in which the Jews have been persecuted, giving examples of the indignities, torments, and brutalities to which Germans subjected them. It shows that even German children, nourished in this antisemitic culture, had taken to defaming and abusing Jews. "It is Christian children that do it, and Christian parents, teachers, and clergymen who allow it to happen." With clarity and directness, Meusel contends that "it is not an exaggeration when one speaks of the attempt to annihilate the Jews." In the presence of this fury of hate and immense suffering, the Church stands idle and mute. "What should one reply to the desperate and bitter questions and accusations? Why does the Church do nothing? Why does it allow unspeakable injustice to occur?" Particularly telling was Meusel's denunciation of the Church's warm welcome of Nazi rule, the Church's avowal of fealty to Hitler's regime. She quotes and concurs with the verdict of a Swedish report "that the Germans have a new God, and it is The Race, and to this God they bring human sacrifices." "How can it again and again profess joyous loyalty to the National Socialist state?" wonders Meusel. Alluding to the Nazi doctrine that decreed humaneness to be a base and contemptible sentiment, she asks: "Does it mean that all that is incompatible with humaneness, which is so disdained today, is compatible with Christianity?" In dire words of surpassing accusatory harshness, Meusel warns the Church: "What shall we one day answer to the question, where is thy brother Abel? The only answer that will be left to us as well as to the Confessing Church is the answer of Cain."

The German churches provide a crucial case in the study of the breadth, character, and power of modern German eliminationist antisemitism, because their leadership and membership could have been expected, for a variety of reasons, to have been among the people in Germany most resistant to it. The churches retained a large measure of their institutional independence, they contained many people who regarding other matters harbored non-Nazi and anti-Nazi sympathies, and their governing doctrines and humanistic traditions clashed glaringly with central precepts of the eliminationist project. The abundant evidence about their leadership's and membership's conceptions of Jews and stances towards the eliminationist persecution merely confirms and, because it is a crucial case, further strengthens greatly the conclusion that among the German people, the Nazified conception of Jews and support for the eliminationist project was extremely widespread, a virtual axiom.

Not only the churches and their leadership but also, as was shown in Chapter 3, virtually the entire German elite—intellectual, professional, religious, political, and military—embraced eliminationist antisemitism wholeheartedly as its own. The German elite and ordinary Germans alike failed to express dissent from the Nazi conception of Jewry in 1933, 1938, 1941, and 1944, although the nature and status of the Jews was one of the most relentlessly discussed subjects in the German public sphere. No evidence suggests that any but an insignificant scattering of Germans harbored opposition to the eliminationist program, save for its most brutally wanton aspects. Even violent anti-Nazi diatribes typically did not dwell on the eliminationist antisemitism or measures as reasons for hating and opposing the Nazis.42 Germans not only failed to indicate that they believed the (by non-Nazi standards) criminal treatment of the Jews to be unjust. They not only failed to lend help to their beleaguered countrymen, let alone foreign Jews. But even worse for the Jews, so many Germans also willingly aided the eliminationist enterprise. They did so by taking initiative to further it, by attacking Jews verbally and physically, or by hastening the process of excluding and isolating them from German society and thereby accelerating the process of turning Jews into socially dead beings and German Jewry into a leprous community.

It is often said that the German people were "indifferent" to the fate of the Jews.43 Those who claim this typically ignore the vast number of ordinary Germans who contributed to the eliminationist program, even to its exterminationist aspects, and those many more Germans who at one time or another demonstrated their concurrence with the prevailing cultural cognitive model of the Jews .or showed enthusiasm for their country's anti-Jewish measures, such as the approximately 100,000 people in Nuremberg alone, who, with obvious approval, attended a rally on the day after Kristallnacht which celebrated the night's events. Those who postulate that "indifference" governed the German people proceed as if all these Germans, who either openly assented to or were complicit in the eliminationist program, were a trivial number of people, and as if we learn from these Germans' actions nothing about the character of the German people in general. Ignoring, for the moment, these fundamental, unsurmountable empirical and analytical problems in asserting that Germans were "indifferent" to their national project of persecuting and exterminating the Jews, the invocation of "indifference" suffers from fatal conceptual problems as well.

Before the concept of "indifference" should be used, at least two issues must be addressed. The first is its meaning. How could Germans have been "indifferent"—in the sense of having no views or predilections on the matter, in the sense of feeling no emotions, of being utterly neutral, morally and in every other way—to the mass slaughter of thousands of people, including children, which the people themselves or their countrymen were helping to perpetrate in their name? Similarly, how could Germans have been "indifferent" to all of the earlier eliminationist measures, including the forcible wresting from their own neighborhoods of people (Jews) who had lived there for generations? The public vitriol against Jews was so ubiquitous in Germany during its Nazi period that it was as impossible for Germans to have had no views about Jews or about the elimination of Jews from German society as it was for Whites in the American South during the heyday of the civil rights movement to have had no views about Blacks or about the desirability of desegregation. "Indifference" was a virtual psychological impossibility.44

If, however, somehow "indifference" existed, if somehow many Germans had no views about Jews and no views about the justice of what their countrymen were doing to the Jews, then this cognitive state still must be elucidated, which would not obviate the problems of using the concept, but lead to the second issue. Germans, like others, were not indiscriminately "indifferent" to all matters. So why would they have been "indifferent" to the slaughter of Jews but not to many other occurrences that, on the face of it, should have been less likely to have stirred them from a state of total neutrality than would the eliminationist measures that culminated in mass murder? The structure and content of cognition and value and the nature of social relations that would produce "indifference" (if indeed it ever obtained) to such radical and unnerving measures as the anti-Jewish program in all its facets must be explicated if the concept is to have any meaning—if it is to be more than a label to be slapped on the German people, a label which prevents considered analysis of the difficult issues.

The psychologically implausible attitude of "indifference" should not be projected onto the Germans who lived through (let alone those who contributed to) the process of turning the Jews into the social dead, who all over Germany stood by with curiosity and watched the synagogues burn on Kristallnacht (let alone those who applauded that night's events), who observed their countrymen deport their Jewish neighbors (let alone those who jeered them), and who witnessed or heard about the exterminatory slaughter. Instead, it would be better to recall from W. H. Auden lines that could have been written for the millions of Germans who watched the events unfold:

Intellectual disgrace stares from every human face, and the seas of pity lie locked and frozen in each eye.45

Indeed, the evidence indicates not Germans' "indifference," but their pitilessness. 46 It is oxymoronic to suggest that those who stood with curiosity gazing upon the annihilative infernos of Kristallnacht, like the "thousands, probably tens of thousands of Frankfurters,"47 looked upon the destruction with "indifference." People generally flee scenes and events that they consider to be horrific, criminal, or dangerous. Yet Germans flocked to watch the assaults on the Jews and their buildings, just as spectators once flocked to medieval executions and as children flock to a circus. The evidence for the putative, general German "indifference," as far as I can tell, is typically little more than the absence of (recorded) expression with regard to some anti-Jewish measure. Absent any evidence to indicate otherwise, such silence far more likely indicated tacit approval of measures which we understand to have been criminal, but which "indifferent" Germans obviously did not.

After all, there is usually a natural flow of sympathy for people who suffer great wrongs. As Thomas Hobbes' exposition of pity underscores, the Germans should have felt great compassion for the Jews: "Pity is imagination or fiction of future calamity to ourselves, proceeding from the sense of another man's calamity. But when it lighteth on such as we think have not deserved the same, the compassion is greater, because there then appeareth more probability, that the same may happen to us; for the evil that happeneth to an innocent man may happen to every man."48 What in Germans blocked the natural flow of compassion? Something must have. Would Germans not have been overcome with pity, would they have been "indifferent," would they have been so silent, if they had been witnessing the forced deportation of thousands of non-Jewish Germans? Apparently, they did not conjure up this "fiction of future calamity" to themselves when this happened to Jews. Apparently, they did not believe themselves to have been watching Hobbes' "innocent" men.

At the same time that Germans quietly or with open approval watched their countrymen persecute, immiserate, and kill the Jews, many of these same Germans were expressing dissent from a wide variety of governmental policies. For these other policies, including the so-called Euthanasia program and often the treatment of "inferior" races of foreigners as well, many Germans were anything but indifferent. They were possessed of a divergent cognitive map, a will to oppose these policies, a will that moved them to work actively to block or subvert them, even in matters that could have resulted in punishment as harsh as any that they would have received for having aided Jews. Tomes have been written on discontent and resistance in Germany during the Nazi period, filled copiously with examples of each, yet virtually nothing has come to light to lend credence to, let alone substantiate, the belief that Germans departed from essential features of the Nazi conception of Jews, viewed the persecution of the Jews as immoral, and judged the regime as a consequence to be criminal.49

This is not surprising, for no alternative, institutionally supported public image of the Jews portraying them as human beings was available on which Germans could have drawn. In fact, every significant institution in Germany supported a malevolent image of Jews, and virtually every one of them actively contributed to the eliminationist program, many even to the extermination itself. Again, it must be asked of those who hold that a large number of Germans were not governed by eliminationist antisemitism to explain and show from where and how—from what institutions, from what church sermons, from what literature, from what schoolbooks—these Germans were supposed to have derived a positive image of Jews. Against this view stands the entire public conversation in Germany during the Nazi period and the overwhelming majority of it before Nazism, as well as the confession of one former Einsatzkommando executioner that he and his countrymen were all antisemites. He explains why: "... it was hammered into us, during years of propaganda, again and again, that the Jews were the ruin of every Volk in the midst of which they appear, and that peace would reign in Europe only then, when the Jewish race is exterminated. No one could entirely escape this propaganda ..."50—which was but the loudest part of the general societal conversation about Jews. The antisemitism of Germans was already so poisonously pernicious before this intensive public barrage of the regime that one Jewish refugee, who left Germany well before the worst isolationist and eliminationist measures, ended his account of the first months of Germany's existence during its Nazi period by explaining with theoretical perspicacity: "I left Hitler's Germany so that I could again become a human being."51 Another Jew, one who remained, summarized the stance of the German people towards the socially dead Jews definitively: "One shunned us like lepers."52

In light of the ubiquitous demonizing, racial antisemitism in the public sphere, in their communities, and among their countrymen, given, just as crucially, the long history of an intense, culturally borne antipathy and hatred of Jews, and given the long support prior to Nazism of major German political, social, and cultural institutions for the eliminationist antisemitic worldview, it is hard to justify, either theoretically or empirically, any conclusion but that a near universal acceptance of the central aspects of the Nazi image of Jews characterized the German people. Eliminationist antisemitism was so widespread and deeply rooted that even in the first years after the Second World War, when all Germans could see the horrors that their antisemitism and racism had produced (as well as its consequences for Germany, namely Germany's lost independence and condemnation by the rest of the world), survey data as well as the testimony of Jews in Germany show that an enormous number of Germans remained profoundly antisemitic.53

Just as the evidence is overwhelming that eliminationist antisemitism was ubiquitous in Germany during the Nazi period, it is equally clear that it did not spring forth out of nowhere and materialize first on January 30, 1933, fully formed. The great success of the German eliminationist program of the 1930s and 1940s was, therefore, owing in the main to the preexisting, demonological, racially based, eliminationist antisemitism of the German people, which Hitler essentially unleashed, even if he also continually inflamed it. As early as 1920 Hitler publicly identified that this was the character and potential of antisemitism in Germany, as he himself at the time explained in his August 13 speech to an enthusiastically approving audience. Hitler declared that the "broad masses" of Germans possess an "instinctive" (instinktmässig) antisemitism. His task consists in "waking, whipping up, and inflaming" that "emotional" (gefühlsmässig) antisemitism of the people until "it decides to join the movement which is ready to draw from it the [necessary] consequence."54 With these prophetic words, Hitler displayed his acute insight into the nature of the German people and into the way in which their "instinctive" antisemitism would be activated by him for the necessary consequences, which he made clear elsewhere in the speech would be, circumstances permitting, the death sentence.

That what Hitler and the Nazis actually did was to unshackle and thereby activate Germans' pre-existing, pent-up antisemitism can be seen, from among numerous other episodes, in a letter from the Office of the Evangelical Church in Kassel to its national Executive Committee that indicts both the Church and ordinary Germans for their newly liberated eliminationist ardor in persecuting Christians who were born as Jews:

At the Evangelical Church one must level the grave reproach that it did not stop the persecution of the children of her faith [the baptised Jews]—in— deed that from the pulpits she implored [God's] blessing for the work of those who worked against the children of her faith—and at the majority of the Evangelical faithful the reproach must be leveled that they consciously waged this struggle against their own brothers in faith—and that both Church and Church members drove away from their community, from their churches, people with whom they were united in worship, as one drives away mangy dogs from one's door.55