1

The Outsider

We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.

— Winston Churchill

During the early half of the twentieth century, in the aftermath of two world wars and a half-century of persecution and violent riots and massacres in Eastern Europe — pogroms that saw many attacks on Jews in the Russian Empire — many from these ethno-religious communities immigrated to Canada in growing numbers. A large percentage settled in downtown Toronto and the surrounding suburbs. That was the case with the family of Jack Starr, the original owner of the Horseshoe Tavern, an outsider with the vision to start things up and a man who saw the potential in 368–370 Queen Street West.

Starr’s father, Louis — simply called “Pa” by his great-grandson Gary Clairman, as well as by all who knew him — was born in Russia; he was a member of the Russian cavalry during the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05). Supposedly, he was also the bugler in the troop. Japan won the year-long battle that forced Russia to abandon its expansionist policy in the Far East. During the short conflict, Pa, fighting at the front, was shot straight through the heart. Somehow he survived. When the war was over, he, along with the rest of his troop, was briefly arrested for desertion because there had been no communication informing their superiors the conflict had ended. His bravery, sense of adventure, and ability to survive are traits the elder Starr passed on to his son Jack, one of seven children. This dogged determination, entrepreneurial spirit, and can-do attitude served Jack well through the years, and he became an astute small business owner.

By the time the second decade of the twentieth century arrived, Starr’s grandfather was tired of the politics, strife, and continual persecution in Eastern Europe. Like so many Polish and Russian Jews before him — and after him — he immigrated to Canada with his wife and two children to provide them with a better life. The Starrs settled on a farm in Whitby, Ontario, right where the 401 exit ramp to the Toronto suburb sits today. Jack was born in 1913 on this rural property. For years, the Starrs used the farm as a way station and inn for Jewish kosher peddlers trying to eke out a living. Later, the family moved to downtown Toronto, buying a house at 153 Manning Avenue, near Dundas and Bathurst.

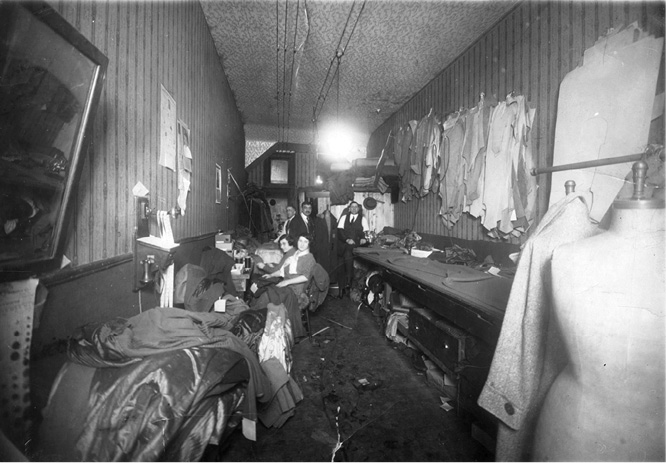

To mark the Sabbath many Jews did not work on Saturdays, making it difficult for some of these immigrants to get factory jobs. Instead, these new Canadians often started their own businesses and hired their friends and family to work for them. During the early to mid-twentieth century, the garment industry exploded in downtown Toronto and other North American cities, like New York. For a period, the clothing industry was one of the biggest employers in the United States, producing 95 percent of the country’s garments. A similar trend occurred north of the border. Early on, the industry in Canada employed mainly Italians and Eastern European Jews, who called it the schmatta business (Yiddish for “rags”).

Starr was one of the early entrepreneurs who found success in this line of work. In his early twenties, the hard-working first-generation Canadian started in the garment manufacturing business, first learning the trade working as a cutter in a women’s wear factory. Before he owned a store of his own, he and his brothers owned a manufacturing company called Hollywood Shirt. Located downtown in what was then referred to as “Schmatta Alley,” the clothing manufacturer made shirts and other clothes and did a large amount of business through the Sears catalogue. Jack later sold his share of the business to two of his siblings and struck out on his own to begin his next venture: Hollywood Skirt.

Postwar Toronto in the late 1940s and early 1950s was considered a bastion of provincial conservatism, but as more immigrants arrived, and more liquor licences were granted, this perception changed. Toronto evolved into a progressive, cosmopolitan centre of commerce and industry. Queen Street West in the fifties was a working-class neighbourhood inhabited mainly by Italians and Jews.

A Toronto garment workshop, circa 1920s, shows Jewish workers operating sewing machines.

Flash back to 1947. Starr — quiet, congenial, and soft-spoken — surprised his family by purchasing the building at 368–370 Queen Street West from Warren Drug Co. Ltd., with a plan to open a restaurant and bar.

Prior to becoming the Horseshoe Tavern we all know and love, this property, at the edge of Toronto’s garment district, changed hands constantly. The building first housed a blacksmith in 1861; later, it shared the space with an engineer and a pair of butchers. Over time, machinists, greengrocers, and many other commercial businesses — from clothing and footwear retailers to the aforementioned drugstore — called the address home. Nothing ever really stuck for long until Starr arrived with his vision.

While it’s a coincidence that a stable once resided in the space of Starr’s tavern, it’s appropriate — in the ensuing years the Horseshoe became home to some of the top acts from Nashville and the stomping grounds for future members of the Grand Ole Opry. Since the property also once housed a blacksmith’s shop, it’s possible that’s where Starr came up with the name. Or, perhaps he was not aware of this historical fact and the name came about simply because he sensed the property, like a horseshoe, was lucky. What is known is that Starr was dabbling in real estate at the time, and the purchase surprised his family. Daughter Natalie Clairman, née Starr, recalls having just come home from summer camp when her father shared the news that he was leaving the ladies’ wear manufacturing business: “Honestly, I don’t know what put that bee in his bonnet. I think he just got tired of doing that and somehow he got it into his head to open a restaurant.”

Over the course of months of sweat and hard labour, Starr invested about $150,000 into the business and built the tavern from the ground up. First, he gutted the building, knocking down the clapboard stores that then occupied the site. Then, he put in a kitchen, a bar, and seating for close to one hundred patrons. At the time, the new, loosened provincial liquor licence laws (circa 1947) permitted Starr to convert the commercial property to an “eatery-tavern” and start serving alcohol. Naturally, he started the process to obtain one of the city’s first liquor licences. This took time and caused Starr some stress. Dealing with government bureaucracy was no different in Starr’s time than it is today. Forms needed to be filled out, criteria met, and papers signed, and then one had to wait for approval from the Liquor Licensing Board of Ontario (LLBO).

Some of the biggest opponents to bars such as Starr’s obtaining the right to sell liquor either with or without meals were clergy. Reverend J. Lavell Smith of the Church of All Nations, up the street from the Horseshoe Tavern at 423 Queen Street West, denounced the granting of licences to all restaurants in the vicinity of his church. “There are enough drunks on Queen Street as it is, and there is [no] need for more outlets,” he told the liquor board. “We had two drunks barge in to our service the other night.”

Did Starr bribe someone with a bag of cash to get the paperwork approved and to expedite the government’s stamp of approval? There’s no one left alive to confirm whether this rumour is true. No matter, eventually Starr succeeded — securing the second Ontario licence granted by the newly created LLBO, shortly after the Silver Rail on Yonge Street, which opened earlier that year on April 2.

When Starr tried to patent and register the tavern’s name, he ran into another stumbling block. As Natalie Clairman recalls, “He initially had a really hard time getting the name ‘Horseshoe’ patented because of the similarity to Billy Rose’s famed Diamond Horseshoe nightclub in New York City … there was some sort of infringement rights; eventually, he got it. Where he got that name from, I honestly don’t know, because my dad never went to the races and he wasn’t a gambler. Maybe he just thought it would be lucky.”

A postcard of the Horseshoe Tavern depicting what it looked like, circa the early 1950s.

Luck certainly played a part in Starr’s early success. On December 9, 1947, the Horseshoe Tavern officially opened. In the December 12, 1947, edition of the Toronto Daily Star, an ad for the newly opened establishment called it Toronto’s “Finest Eating Place” and proclaimed, “It’s the Rave of Toronto! You and your friends are cordially invited to the newly opened Horseshoe Tavern, where the delicious food and distinctive atmosphere is second to none.… Sunday dinner served from 2 to 8 p.m.”

Starr’s idea was to run a tavern for the city’s workers and “outsiders,” those not part of the social elite — the blue-collar toilers in the garment and textile factories, the cops who kept the streets safe, other downtown denizens and not-so ne’er-do-well characters, wayfarers who roamed the city streets. The tavern’s first licence had a legal capacity of eighty-seven seats. In those early days, the bar’s focus was on value: good food, cold beer, and liquor. Another first, according to Time magazine: the Horseshoe was the first bar in Canada to have a television. This happened in 1949.

Starr expanded the space over the years, buying the property next door and enlarging the Horseshoe until it eventually sat five hundred patrons. Soon, live music would rain from the rafters seven nights a week.

Horseshoe stationery.

While he stood only about five foot four, Jack Starr had a big heart and knew a few things about running a business. In a famed picture taken years later with one of his favourite Nashville performers, Little Jimmy Dickens, Starr looks like a giant next to the diminutive four foot eleven rhinestone cowboy. Like his personality, the shows Starr booked and promoted were always larger than life. The room had a barn-like vibe then, and even though it’s half the size today, it still feels like a rural retreat.

There’s no sensible reason why a tavern that hosted country music ended up on this stretch of street. Despite this anomaly, Toronto music lovers around the world are thankful. What did Starr know about running a bar? Not much, but he knew how to run a successful business. And, he was also driven — possessing a work ethic inherited from his father. During the years he ran the bar, he rarely left. He was a fixture at the door; after the doorman, he was usually the next person who greeted you upon entering the building. Before shows and during intermissions, he’d walk from table to table saying hello to the regular patrons, making sure his adopted family always enjoyed themselves.

Starr left a lasting impression on all the artists who played within those four walls, as well as with all the men and women who drank a cold beer on a stool in the front bar or stopped in for a late-afternoon game of pool. Starr was fair. Everyone respected him. Natalie Clairman recalls, “People loved him. He quickly became a fixture on Queen Street. All the policemen knew him, including all the undercover cops. They never paid for a drink in his bar.

A view of the cityscape near Queen and Spadina in the mid-1920s near the intersection where Jack Starr would later open the Horseshoe Tavern.

Every Christmas, he would host a big party at the Horseshoe for the police. All the people from the schmatta business also knew him too … he was very friendly and very outgoing.”

Starr was also a regular at neighbourhood restaurants like Lichee Garden, which opened in 1948 and boasted an enormous dining room with a capacity to serve as many as 1,500 customers a day. Provincial and federal political leaders and other celebrities often dined there. Lichee Garden even had a band and offered dining and dancing until closing at 5:00 a.m. Whenever Starr showed up, a murmur of excited chatter would go through the place; everybody knew his name and loved to see him. Clairman remembers a dad she rarely saw during those early days when he was running and expanding the business: “It was a night business. He would go into the club after dinner, stay until it closed, and be there early the next morning to tally up the bar sales from the previous night and do inventory.”

An avid and accomplished golfer, Starr took rare breaks from running his beloved tavern in the summers to tee it up at Oakdale Golf and Country Club, near Downsview, where he was a member. A newspaper report from 1954 mentions Starr winning the annual Toronto Hotel Association Championship. Following his round, the businessman sometimes took an afternoon siesta before heading back to the bar. Some of Gary Clairman’s earliest memories, as a nine-year-old, are of going down to the bar on a Sunday afternoon, eating a banquet burger with fries, and just hanging out with his grandpa. He recalls:

(Top and bottom) Looking eastward on Queen Street to Spadina Avenue on October 12, 1933, fourteen years before Jack Starr opened the Horseshoe Tavern at 368–370 Queen Street West.

Sometimes, if I slept over at my grandparents’ house, Jack would get up and we would go down to the Horseshoe together before it opened. There was a trapdoor behind the bar where he kept the safe. That room is still there. He would open the safe, and it would be full of one-dollar bills because everything from a beer to a shot of liquor cost one dollar in those days. There would be stacks and stacks and stacks of ones. I would help him count them. Then, we would put them in bundles of twenty-five or fifty to take to the bank.

In later years, these family moments at the Horseshoe Tavern continued. As Pa was then in his nineties, living alone in an apartment, Starr would pick up his dad at 8:00 a.m. and take him down to the bar. While Starr tallied up the receipts and took inventory from the previous night’s sales, his dad kept busy. Natalie Clairman recalls, “My grandfather would take a shot glass, go around the bar and pour the rye, Scotch, and gin — the dregs of whatever was left in the glasses on all the tables into his glass — then he would sit in a chair, drink it back, and fall asleep for the rest of the morning until Jack took him home!”

Despite the presence of lowly citizens who were regular barflies at the Horseshoe, fights were rare. Mixing with these drifters and law-abiding country and western music lovers were detectives — rough, hard-nosed characters — as well as criminals in the making who turned to the wrong side of the law to survive and make ends meet. These bookies, bootleggers, and bank robbers were the people below the veneer of the city’s stereotype of “Toronto the Good.” One of the tavern’s most famed patrons in those early years was the mastermind bank-robbing bandit Edwin Alonzo Boyd, who later escaped not once — but twice — from Toronto’s Don Jail, and other members of his notorious gang drank there as well.

Sergeant of Detectives Edmund “Eddie” Tong’s old battered Buick was often seen parked outside one of the many newly opened taverns in downtown Toronto, including the Horseshoe, during those years. As Brian Vallée writes, “People called Tong ‘the Chinaman’ because of his name and his black hair, which he combed back off his forehead.” Tong kept an eye on the underbelly of Toronto, where the likes of Boyd and his gang dwelled. Starting in 1949, the cop routinely visited places like the Silver Rail on Yonge Street, the Holiday Tavern at Queen and Bathurst, and the Horseshoe Tavern at Queen and Spadina. Since opening and being some of the first establishments to obtain liquor licences in the province, these bars had quickly become the watering holes of choice for Toronto’s criminals and their hangers-on. Tong and his partner at the time, Jack Gillespie, would go into the bars just to let these patrons know they were around and they were watching.

Barkeep Lennie Jackson was a drifter, a pool shark, and one of these hangers-on; he landed a job at Starr’s tavern after moving to Toronto from Niagara Falls. As Vallée writes, “It wasn’t long before Lennie Jackson decided he wanted some of the better things in life, and that the way to get them was not by waiting on tables in a bar, but by robbing banks.” Jackson ended up quitting the Horseshoe and becoming a wanted man for his role in a series of bank robberies with the Boyd Gang. He was eventually shot by Gillespie, but not before he and his fellow partner in crime, Steve Suchan, shot and fatally wounded Tong in March 1952.

While there are a couple of old newspaper stories about shootings near the Horseshoe in the 1950s, these events were rare. Asked about this by the Globe and Mail, long after he had retired and the bar was set to celebrate its fortieth anniversary, Starr, then seventy-seven, replied, “Oh, there were a few freak incidents like that. In the early days, we spent about 90 percent of the time at the door keeping out the type of people we didn’t want in. But over the years we had a cross-section of all kinds: college kids, doctors, lawyers, and businessmen.”

Besides this eclectic cast of colourful characters, most of Starr’s regular patrons were good-time folks from the East Coast. Daughter Natalie Clairman remembers, “At a time when the economics in the Maritimes was not very good, they were migrating to Toronto. They were country music fans, so they eventually persuaded my dad to bring in some music. It sounds simple, but that’s as simple as it was.” Adds Natalie’s son, Starr’s grandson Gary Clairman, “I’m sure Jack became a fan of country music, but it’s not like he was playing it around the house. He was smart enough to know though that it was going to fill the place.”

The country and western acts certainly helped pack the establishment. Beginning in the early 1950s and lasting until he retired in the mid-1970s, Starr’s booking policy helped fill the Horseshoe’s coffers for twenty-five years. Marvin Rainwater was the first act Starr hired. Rainwater, an American country and rockabilly singer and songwriter, had several hits during the late 1950s, including “Gonna Find Me a Bluebird” and “Whole Lotta Woman” — a number one record in the United Kingdom. The musician was known for wearing stage outfits based on traditional aboriginal clothing; he was part Cherokee.

The first country performer, though, was Shorty Warren, from Jersey City. As Starr later told the Globe and Mail, “Country music was not a socially accepted genre at the time, so the tavern provided an escape for country music lovers.”

Starr’s business acumen, marketing and promotional powers quickly built the Horseshoe Tavern from an intimate eighty-seven-seat restaurant serving food, beer, and liquor, and catering to a neighbourhood clientele, to a five-hundred-seat music venue serving the growing musical needs of expats and migrant workers from Atlantic Canada — and also satisfying the growing legions of Hogtown’s country music fans. Stompin’ Tom Connors recalls this reputation in his second memoir: “Everybody who was a country fan and who landed in Toronto for any reason, either by plane, car, bus, or train, for any length of time, sooner or later wound up paying a visit to the Horseshoe.”