11

Ushering In a New Era

Change is inevitable. Change is constant.

— Benjamin Disraeli

Change came to the Horseshoe again around 1995, when Jeff Cohen, known by most as simply J.C., and his partner Craig Laskey arrived at the ’Shoe. They were invited by Sprackman to usher in the modern era for the storied tavern. If the shoe fits, wear it. And that’s exactly what Cohen did when he arrived at the Horseshoe. He knew the venue needed to change its course. That was a given. What wasn’t so clear, at first, was what direction he and his partner Laskey would take it in.

Jeff Cohen was born and raised in Montreal. After high school, he moved to Ottawa to attend Carleton University. It was only two hours away from home, and he could get there easily by car, bus, or train. “That’s where I first gained my independence,” Cohen says.

While in the nation’s capital, Cohen spent more time at the campus radio station, CKCU FM, than in the classroom. That’s where his real education happened, and eventually he dropped out of school to work full-time at the station. From 1981 to 1991, he worked as a DJ, doing sports and public affairs and playing punk rock music. He laughs when he tells me the only reason he remembers the year he started there was because that was the first and only time his beloved Montreal Expos made the post-season.

“I was a muzoid,” recalls Cohen. “That era was the right time, as it saw one of the greatest explosions in rock ’n’ roll. I learned more in a three-minute record than I ever learned in school. I failed three times, and eventually Carleton kicked me out.”

As luck would have it, Cohen was surrounded by a lot of young, bright minds at the station, many of whom would go on to great success in the music industry. The program director at CKCU was Nadine Gelineau. After leaving the campus radio station, she would go on to work for BMG Canada and later start a North America–wide music marketing and branding agency called the MuseBox. Sadly, she passed away in April 2016. Another colleague, John Westhaver, now runs the biggest independent music store in Ottawa: Birdman Sound. “There was a bit of an incubator going on,” Cohen says. “I fell into that scene.”

Later, as Cohen was forging his own path in the music industry — a long, winding road that eventually led him to the hallowed space at 370 Queen Street West — he relied on many of these early mentors he met while working at CKCU.

While at the station, Cohen took on a series of successive roles that kept building the skills he would need the day he took over the ’Shoe. First, he became the fundraising director for the non-profit station. One way he achieved this was by putting on CKCU-sponsored concerts. Bands he booked included Rheostatics, U.I.C., the Gruesomes, Fugazi, Ministry, Circle Jerks, the Dead Milkmen, and Henry Rollins. Mostly, these were bands with a punk rock attitude. He made the station money, and he says that’s where he first learned to become a promoter. Later, he started an all-ages club called One Step Beyond that hosted a lot of live music. After two years, the venture failed. It was time to try something new.

Out of work and in love, Cohen moved to Toronto to chase a girl. Unfortunately, she wasn’t as interested and never went out with him again. It was around September 1992. Cohen arrived in the big city adrift and alone. He had no sense of what he was going to do next. He only knew three people in town: Dave “Bookie” Bookman, whom he had met through his band the Bookmans when they had played in Ottawa; Elliott Lefko, a Toronto promoter who went on to become a big talent buyer across North America; and Fred Robinson, from the punk band U.I.C. None of them had any association with the Horseshoe Tavern.

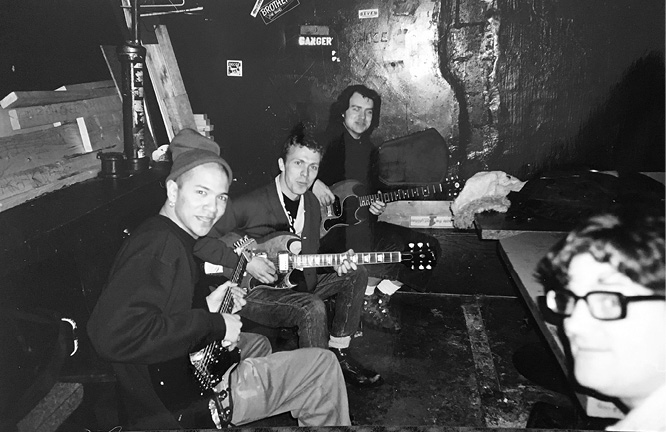

The Smugglers, from Vancouver, pictured here in the basement dressing room prior to their gig at the Horseshoe on February 12, 2000.

Cohen decided to start by tapping in to his decade of experience at the community radio station in Ottawa. He approached CIUT (89.5 FM), the campus station for the University of Toronto, and got on the air as a volunteer, hosting an overnight show. With his ten years of radio experience, it wasn’t long before the station gave him his own show called Mods and Rockers, which featured punk, ska, and mod music.

Within six months of landing in Toronto, however, Jeff still didn’t have a full-time job. He wasn’t yet promoting any shows, as it appeared there were already enough promoters in town. But when he wasn’t on air, he started to make the rounds and schmooze with the doormen and managers at all the live music venues that mattered: the Rivoli, the Diamond Club (now the Phoenix), and the Horseshoe.

At the same time, his Mods and Rockers show took off. Elliott Lefko liked his show, and his buddy Bookman, who was a broadcaster at CFNY (102.1 The Edge), started introducing him to other people in Toronto’s music scene. At some point during that time, Cohen remembers receiving a phone call from William New, lead singer of Groovy Religion and the head bartender at the Apocalypse Club, and the inventor of Elvis Mondays. He said to Cohen, “Elliott used to be the talent buyer at the Apocalypse, but he left. I’ve taken over, and I’m losing money at the bar because I can’t book it that well. Have you ever done this before?”

Cohen says he thought, I’ve fundraised for a radio station, I can do this. A deal was soon reached for Cohen to come on board at New’s club for a three-month trial. Like that, he had his first paying job in Toronto. For the next few years, that’s where he cut his teeth and continued to build up his reputation among the rest of the industry players. It’s not clear whether Sprackman was watching Cohen at this stage, but it wouldn’t be too long before he learned about his future partner and the person who would be the perfect fit to take the Horseshoe Tavern into the new century.

At the Apocalypse, Cohen was booking mostly punk and garage rock bands. Later, he dabbled a bit in speed metal. There were some memorable shows there, including a double bill featuring two bands from the United Kingdom, Snuff and Bad Manners. For most of us, as we age, our musical tastes evolve. Cohen, just entering his thirties, started to dig the blues. Albert’s Hall, the top floor of the Brunswick House on Bloor Street, was the venue at the time. They brought in some legendary performers for week-long residencies. As his path of musical discovery continued, he learned more about offshoots of the genre, like zydeco and soul. Somehow, through this journey, he became friends with the Bourbon Tabernacle Choir, a rhythm and blues and funk fusion alternative band formed in 1985. By the early 1990s, they were holding court on campus radio. “They are one of the greatest Canadian bands that ever existed, regardless of how far they went or didn’t go,” says Cohen. “They are one of greatest live bands I have ever seen. They were all ex–punk rockers who got into soul and the blues. I started hanging out with them a lot, especially Chris [Brown].”

Eventually, around 1994, Cohen became a consultant for the Bourbons. Through them, he got introduced to their accountant, Lawrence Sprackman, Kenny Sprackman’s brother. One of the final pieces of the puzzle that led him to the Horseshoe was then in place. After three years, Cohen quit the Apocalypse Club and started to promote his own shows at various venues around town.

Work at the Mariposa Folk Festival, at the El Mo as a booking agent and club talent buyer, and for the Agency as an agent for a brief stint, followed. Heck, Cohen figured an agent was one of the few jobs he hadn’t done yet in the business, so he rolled the dice. That’s where he first became friends with Ralph James, who today is the biggest talent agent in Canada. “I remember him asking me, ‘If you were an agent, who would you sign?’” Cohen recalls. “I told him: ‘Lowest of the Low, Big Sugar, and Rheostatics.’”

Although the Horseshoe wasn’t his room to book (that was James’s territory), Cohen was assigned the Ultrasound and he went on to sign the likes of 13 Engines, Rheostatics, Big Sugar, Lowest of the Low, Big Rude Jake, and Monster Voodoo Machine for that stage. But when Sam Feldman, of the biggest artist management group in western Canada, acquired the Agency, Cohen was let go.

So it was back to the El Mocambo, where Cohen had spent some time earlier in the decade. The club had just reopened yet again with new owners. At that time, Cohen had signed a band named Bender, managed by a guy named Craig Laskey. The two got along, and Cohen asked Laskey to be his assistant. This new partnership lasted for a year at the El Mo before they were fired for not sharing the same direction as the owners. The two remained partners and brainstormed about what would come next.

The Sadies during one of their annual New Year’s Eve performances at the ’Shoe on December 31, 2006.

They had been out of work for only a couple of weeks when Cohen got a call from Lawrence Sprackman asking if he would consider working for his brother Kenny over at the Horseshoe. Bookie, who knew Jeff from their Ottawa days, had also put in a good word with Kenny. “He’s at his wits end,” Lawrence said of his brother’s predicament. “The Horseshoe is not doing well, and he needs help.”

Yvonne Matsell had decided to go back to the Ultrasound full-time, so Kenny Sprackman was desperate for a new talent buyer for the club, someone who had their pulse on the current music scene. Craig and Jeff conferred on the matter and felt the ’Shoe was out of their league. At the El Mo, they booked music three, maybe four nights a week, whereas the ’Shoe was a seven-nights-a-week bar. “At the time, we were managing both 13 Engines and Big Rude Jake and thought maybe we will just go into management full-time,” Cohen says. “The accountant understood our trepidation, but asked if we could do him a favour and just meet with his brother.”

The band Wilco was doing sound check when Cohen and Laskey arrived for their interview with Kenny Sprackman. X-Ray was not there. “Craig was more freaked out about meeting Jeff Tweedy [Wilco’s lead singer] than about the interview,” Cohen says, laughing. “It was the strangest interview I’ve ever had in my life. He [Kenny] wasn’t someone who looked through your resumé. I gave it to him, and he just threw it in the corner. ‘Don’t you have any questions to ask?’ I said. Kenny just looked at Craig and [me] and said, ‘I’ve heard great things from my brother. When can you guys start? Let’s set a figure, and we’re done.’”

To put this bold offer into context, this was after the club’s heyday in the late 1980s and early to mid-1990s. They had weathered the recent recession, but once again, the club was trying to find its musical mojo. “Please help me. This place is an institution,” Kenny pleaded with the pair. Sprackman really hoped the answer to his booking problems lay in these two young musical minds sitting across from him.

Cohen recalls leaving that meeting and telling Kenny his proposition was overwhelming. “We want to do the talent buying, but we need some time to decide.”

It took Jeff and Craig about a month to decide. They put together a plan for the changes they needed to make. At the time, the ’Shoe was a place that wasn’t welcoming to every promoter in town. “We had this vision to make it more open and bring in more Canadian bands,” says Cohen.

Andy Maize, lead singer for the Skydiggers, playing at one of the band’s annual Christmas shows, December 19, 2008.

They would also require some start-up money to implement some of the changes. “For one, there was no advance ticketing in the place,” Cohen adds. “There was not a lot of professionalism in the room, either, as they didn’t have their own sound technician. Kenny gave us carte blanche. ‘Just tell me what you need, and it’s yours,’” Cohen says they were told.

On August 1, 1995, Cohen and Laskey took over the day-to-day booking and talent buying for the club.

Laskey grew up in Port Perry, Ontario. From an early age, music caught his ear. He listened late into the night to the radio waves in his bedroom and started getting fascinated with the live music scene as a teen. “I would go to Toronto by myself and see whoever was playing at Maple Leaf Gardens or the CNE,” he recalls.

Following high school, Laskey attended Durham College, taking the arts and business entertainment program with the dream of working in the live music industry. On the side, he also started managing a few local bands.

After finishing his diploma, he started managing Bender, a band from Orangeville, which Cohen ended up booking; that’s when the pair first met and started a friendship based on a shared love of music. This burgeoning friendship led to Cohen bringing Laskey on board to book bands at the El Mocambo and, later, at the Horseshoe. Asked to recall some of the favourite gigs he’s brought to the ’Shoe, the booking agent mentions a handful: Wilco, the Baseball Project (three-fifths of R.E.M.), the Pixies, Link Ray, the Dead Weather with Jack White, Son Volt on a Sunday night, the Strokes’ second-ever Toronto show on a Nu Music Tuesday, Guided by Voices for two nights in 2002, and, of course, all the last-minute Tragically Hip shows. “It’s hard to put into words, but I still get a lot of joy booking the club six nights a week,” Laskey says. “For some bands, it’s a milestone for them just to play the Horseshoe, even if they don’t go on to major fame. It’s special to think I’m a part of that.” Cohen remembers:

When Craig and I came in as talent buyers at the Horseshoe, we worked alongside X-Ray for the first few years. He still had a lot of passion for the music, and we valued his opinion, even though his tastes were not up to speed with what the kids were now listening to. There was no animosity between the three of us. We told him, we want to be like you, but do our own thing. We asked him what he was listening to and tried our best to keep him involved. He really helped us. We picked his mind and sat and listened to music with him in his basement office, which was filled floor to ceiling with cassette tapes.

By the end of that first year, thanks to the pair’s booking policies, they had improved the back bar sales by one hundred thousand dollars. Certain staff didn’t like the changes, which also included signing a deal with Ticketmaster, building the stage a little higher, putting the door staff under Cohen and Laskey’s control (not the owners’), and getting rid of one of the house technicians. They replaced a few staff — realizing they needed personnel in the back bar who knew music. They also kicked out a whole bunch of bands who were used to playing there and getting steady gigs — local favourites like

Bazil Donovan, bassist for Blue Rodeo, performs as part of the Six Shooter Records Outlaws & Gunslingers Americana Music Association Showcase at Canadian Music Fest on March 20, 2013.

Jack de Keyzer and Paul James. Cohen said it wasn’t personal. They were great bands, but their time had passed its prime. “We needed to give new bands like Big Sugar, the Mahones, and Great Big Sea a chance to play here.”

Jeff and Craig brought in some surf and rockabilly bands from the States — stuff X-Ray dug like Dick Dale. They also started paying homage to some unheralded artists from the sixties and seventies like Jimmie Dale Gilmore. “All the while, we were adding our own touch,” says Cohen. “Kenny let us do our thing. We really got that place rocking! At the end of the first year, he asked us to sign on for another two years.”

The pair was having fun, so signing another deal was a non-issue. Their reputation was building, especially among agents like Ralph James, for whom Jeff had previously worked at the Agency. The whole key to the Horseshoe, even when X-Ray was booking it, was that James always had these incredible bands to offer the venue. Somewhere along the line, what happened was that for some reason the ’Shoe was not booking in as many of James’s bands. “He was the one signing a lot of the bands that were a perfect fit for the ’Shoe, so when I took over I also re-established the Ralph James era,” Cohen says. “He built bands’ careers off that stage.”

Miranda Mulholland is all smiles and fiddling about on the Horseshoe stage as part of NXNE 2014 Outlaws & Gunslingers Six Shooter Records showcase, June 19, 2014.

Starting in 1997, Laskey and Cohen started an annual pilgrimage, often joined by X-Ray, to the South by Southwest (SXSW) music festival in Austin, Texas, scouting out new bands to bring north of the border to the Horseshoe. It was there where they discovered many of the alt-country bands for the first time that they would soon book, such as Ryan Adams, the Old 97’s, and Neko Case. The trio hung out, and X-Ray showed them all his favourite spots, including the best place for barbecue: the Green Mesquite. More than twenty years on, Craig and Jeff throw a party at the restaurant every year in honour of X-Ray.

“We made [the Horseshoe] a place people felt comfortable to go to,” explains Cohen. “Elliott [Lefko] from MCA Concerts started putting all of his shows into the Horseshoe. We also had deep connections with Dave Bookman and Kim Hughes at CFNY, and we changed the structure of Dave’s Nu Music Night and it exploded.”

On Bookie’s Tuesday night, the Horseshoe started doing crazy bands like Son Volt, Whiskeytown, the Jayhawks, the Strokes, Goldfinger, and even Foo Fighters. “Everything just clicked,” recalls Cohen. “Our methodology worked for the ’Shoe, and the ’Shoe worked for us.”

The other thing that’s key to the more recent success of the Horseshoe is the creation and establishment of associations and partnerships with music media such as Chart magazine, Exclaim!, and NOW Magazine, and with record labels like Six Shooter Records and Dine Alone Records, along with the independent record stores in town that sell tickets to the shows. “We told all of them, we want a relationship with you,” explains Cohen. “We are all small businesses and in this together.”

Cohen and Laskey initially had opposition from some employees and external partners who didn’t like change. The bar manager in charge gave them a hard time when they first assumed control. And a few publicists and promoters didn’t like the direction they were taking the bar. The reality is that they didn’t like it because it wasn’t friendly to the bands they were promoting. “Some just wanted it to be the way it was ten years ago,” Cohen says. “Some were just not interested in our new vision. They felt that we were straying from the roots music stuff that was at the core of the ’Shoe’s legacy. We didn’t care.”

Instead, thanks to Laskey’s ear and ability to hear a hot band before anyone else, they brought in the likes of Neutral Milk Hotel, Death Cab for Cutie, and The National. Many of the bands they booked were playing Massey Hall or the Air Canada Centre the next time they returned to town. All of them started at the ’Shoe, playing for five hundred bucks. Rheostatics, whom Cohen got to know when they were doing two-week stands at Ultrasound, were convinced to come and do the same length residency at the Horseshoe. This annual stretch of shows that would go on long after last call Cohen dubbed the “Fall Nationals.”

Another thing the pair started in their era was honouring the past by paying respect to the history and tradition of the Horseshoe by celebrating its milestone birthdays, beginning with its fiftieth in 1997. Every year of a major birthday, the bar would have a week-long bash with special programming over the course of four nights, each weekend in December (you’ll recall the Horseshoe opened on December 9 back in 1947). They brought back many of the Canadian bands who had played there and made their mark back in the mid-eighties and early nineties — bands like 54-40, Spirit of the West, the Watchmen, and Blue Rodeo. They also started documenting the new era, decorating the walls across from the bar in the front room with set lists, framed photographs, and newspaper clippings of all the bands that have played there during their tenure. Cohen gives credit to his wife for that idea. “We respect the past, but it’s also about making our own thing go. We’ve mainly collected memorabilia from our era. There are pictures on the walls of Great Big Sea, the Old 97’s, the Jayhawks, and Spirit of the West, all bands who played here from 1994 on.

Horseshoe Tavern part-owner and booking agent Craig Laskey.

“If you are stuck in doing it the same ways it was done before, it’s going to fail,” says Cohen. “No offence to the hipster kids. You have to modernize, but it’s sometimes a fine line. We’ve tweaked the Horseshoe logo over the years, and we now have cash registers that go to a central computer system.”

After three years, Jeff was getting antsy and told Craig they needed to do something different. He told him that he was done working for other people, and then he told Sprackman as well:

If I’m going to do this for a living, I want to own my own club. I need to be an owner, so I told Kenny that we were thinking of leaving. He asked, “What are you going to do?” I said, “The El Mo is sitting there empty. I think we are going to go buy the building and do what we’ve been doing here.”

Kenny just looked at me and said, “I don’t want to compete with you. Do you want to become a partner?” He had no interest in buying another club, so he said, “Why don’t you just buy into the Horseshoe?” [This was February 1998. Cohen was dumbstruck.]

“Is it for sale?” I asked. He said X-Ray was thinking of getting out of the business, to go talk to him, so I went to Austin where X-Ray was spending some time.

He told me he was thinking of getting out: “Can you pay me a decent amount?”

“Of course,” I said, and we reached a deal.

He took a lump-sum payment, and I bought him out. On August 1, 1998, I became an owner of the Horseshoe Tavern. Part of my deal as an owner was to invest fifty thousand dollars into the business.

Horseshoe Tavern majority owner Jeff Cohen.

As part of that capital investment, Cohen put in the first draft taps the Horseshoe had ever had in the front bar.

As owner, Jeff elevated Craig to chief talent buyer. One of the other changes that have been made in the Cohen and Laskey era was increasing the legal capacity from 167 (even though they were cramming 400 people in most weekends) to 468. They kept getting fined by the police or the Alcohol and Gaming Commission, and it wasn’t worth the hassle anymore; it also didn’t make good business sense. Cohen also ended up having to put one hundred thousand dollars into the club to change the HVAC system and upgrade the washrooms. “I modernized the place without taking away its physical beauty,” says Cohen. “We also added new sound systems for the stage, new carpet, but made sure the black-and-white checkerboard tile on the floor made famous by The Hip song remained. We also hired a guy who restored all the wood in the place to make it look traditional. We modernized the banking and credit card point-of-sale payment systems and made ticketing deals with Ticketmaster and Ticketfly. We also set up standardized, more professional relationships with our staff, hired bar managers and a professional accountant. We basically changed the business structure.”

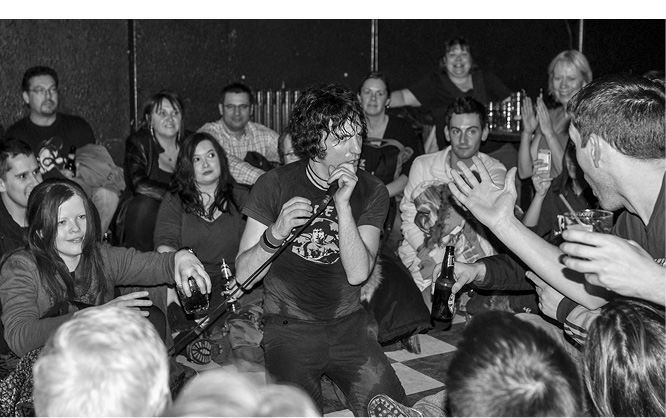

Jesse Malin gets down on his knees and personal with the crowd, singing on the checkerboard floor at the Horseshoe Tavern on January 22, 2011.

They also weren’t afraid to raise prices, when necessary, to keep pace with inflation.

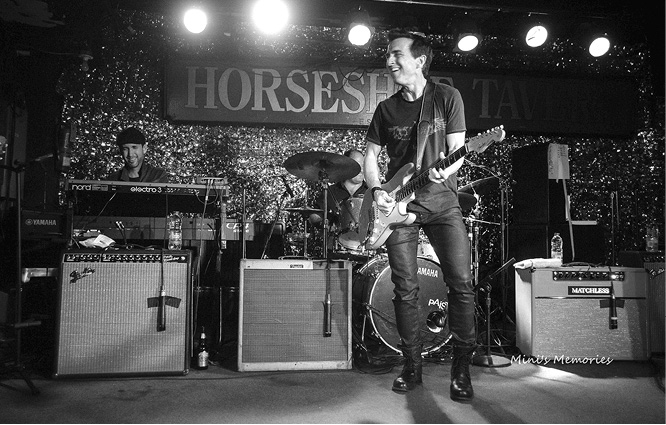

Colin James returned to the Horseshoe Tavern for the first time in twenty years in the fall of 2016 to play a short gig, launching his latest album, Blue Highways.

“Everyone will talk about the music and the bands who played here, but the fact of the matter is a bar does not stay open this long without an owner, whether it’s Kenny, X-Ray, me, the Clairmans, or the original owner, Jack Starr, that has savvy business skills that can make it work in every era,” Cohen explains.

While Cohen bought 50 percent of the business from X-Ray, all the while he learned the ins and outs of the business from Sprackman. Eventually, he started renegotiating the leases with the Clairmans and took over the day-to-day running of the business to the point that Kenny decided to retire in 2005. Sprackman is still a silent partner and owns 15 percent of the business. When he retired, he took 35 percent from his 50 percent and sold 25 percent of it to Craig and 10 percent to the ’Shoe’s in-house accountant Naomi Montpetit. Ever since, the three of them have owned and operated the club. To keep it going, along the line, they’ve expanded their little music empire — from creating a promotion company called Collective Concerts, to buying Lee’s Palace, to more recently running the three-day outdoor Toronto Urban Roots Festival (TURF) each September. “It sounds crazy, but we have the same booking policy we had when we came in back in 1995,” says Cohen.