2

Nashville North

I won’t stay home and cry tonight like all the nights before

I’ve just learned that I don’t really need you anymore

I found a little place downtown where guys like me can go

And they’ve got bright lights and country music

Bright lights and country music, a bottle and a glass

Soon I’ll be forgetting that there ever was a past

And when everybody asks me what helped me forget so fast

I’ll say, “Bright lights and country music”

— Bill Anderson and Jimmy Gateley, “Bright Lights and Country Music”

You can make a case that the high point of the Horseshoe Tavern’s existence was during its heyday as a country music bar. I am not talking about the mainstream country you hear over the airwaves today. I am talking about vintage country, the kind your grandparents tuned in to on their transistor radio after a hard day’s work — listening to a station from Wheeling, West Virginia, or Nashville, Tennessee, at the farthest reaches of their FM dial. From the mid-1950s to the late 1960s at the Horseshoe, lineups around the block were common. The tavern’s stationery proclaimed, “Toronto’s Home of Country Music.” Seven nights a week, honky-tonk tunes spilled out onto Queen Street. Nashville legends — and future Country Music Hall of Fame members — picked and strummed their guitars and sang their timeless songs on the ’Shoe’s stage to adoring audiences. Some of them even recorded albums at Starr’s bar. You could see the admiration all the Nashville acts had for the Toronto venue and for its charismatic owner. Take the famed American bluegrass musician Mac Wiseman, for example. As he writes on the sleeve of his 1965 album Mac Wiseman Sings at the Toronto Horseshoe Club, “The Horseshoe uses top country & western artists fifty-two weeks a year and the great success being enjoyed by this fine club must be attributed to Mr. Jack Starr and his friendly, efficient staff. Mr. Starr is not only a very smart club manager; but he’s also a wonderful person and a true friend of country music. Anytime you are around Toronto, drop in at the Horseshoe, and tell Jack — Mac sent you.”

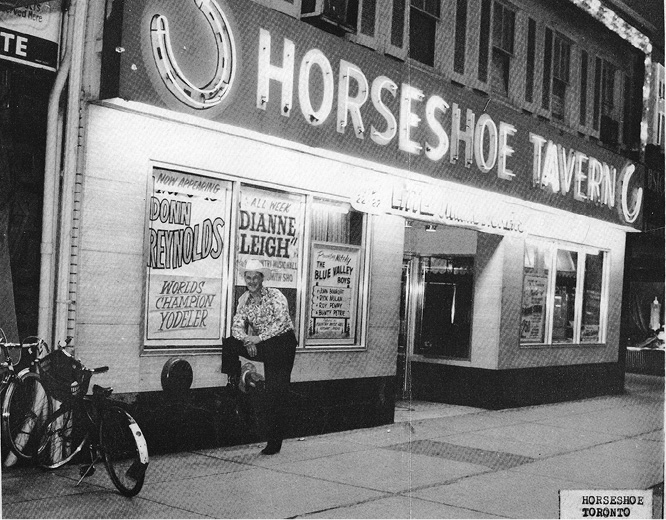

Donn Reynolds, Canada’s “King of the Yodellers,” poses outside the Horseshoe Tavern.

This is a part of the tavern’s rich history few know about. Many of those famous performers from that era have passed on; others have fuzzy memories of those days. Thankfully, a handful of these musicians — and some of the fans — are still around to share their stories. Allow me to transport you back to those good, old country days.

Fifty years ago, the Horseshoe was known in the music industry as Nashville North and was a regular stop for the top country stars of the day, including those great acts from the Grand Ole Opry. The list of performers who graced the ’Shoe’s stage during this period could fill this book. The following is just a sampling of the country heavyweights who played there: George Hamilton IV, Faron Young, Kitty Wells, Bob Luman, Ferlin Husky, Little Jimmy Dickens, the Carter Family, Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Loretta Lynn, Bill Anderson, Charley Pride, and Tex Ritter.

Nearly every country superstar of the time, save Hank Williams, Porter Wagoner, and Buck Owens, played there. Although according to Wayne Tucker, who wrote the definitive biography of Dick Nolan — the leader of the Horseshoe’s house band during this period — Owens, known for pioneering the Bakersfield sound, did make an unannounced, impromptu appearance.

Buck Owens was a big name in the 1960s and his fees were high. For this reason he didn’t actually play the Horseshoe. But one night Buck dropped into the ’Shoe just to hear the music. He was keeping a low profile amongst the crowd and he had asked Dick, the emcee, to keep his presence a secret. Dick knew that Buck had a temper but he ignored his request and announced that he was in the audience. Then to stir the pot he said: “Would you like to hear him sing?” So an angry Owens had no choice but to take the stage and do a number for free.

When the club was full, it was full, which was nearly every night. Bill Anderson, Tex Ritter, and Willie Nelson were some of Starr’s favourite acts. Years later, many performers still recall with fondness the genteel Jewish businessman who treated them so well: “Every Christmas, there were a load of turkeys in the backroom for the band,” recalls Roy Penney, who played lead guitar in the house band in the 1960s. “He and I used to swap cufflinks; that was our annual tradition. He always treated the band well. On Saturday matinees we would get a big steak dinner on the house.”

Russell deCarle, founder of Prairie Oyster, shares a story about a time when, years ago, the six-time Juno Award winners were rehearsing for an album in Nashville at SIR Studios and Waylon Jennings was getting ready for a tour and rehearsing in the same space: “We would meet at the water cooler and have a coffee with Waylon every afternoon for about half an hour for four days. One of the first things he asked, when he found out we were from Ontario, was about Jack Starr and the Horseshoe … he had nothing but great memories of working there.”

Live music had come to the Horseshoe in a roundabout, unorthodox way. Some of Starr’s most loyal customers were blue-collar workers; many were Maritimers who had arrived in Toronto in the fifties and sixties looking for jobs. Similar to Starr’s own father’s reasons for journeying from Eastern Europe to Ontario, these dreamers sought opportunities and better lives for their families. In an editorial called “Finding the Heart of Canada,” published in the Toronto Star on May 7, 2002, Bernard Heydorn, author of Walk Good Guyana Boy and a past member of the Star’s community editorial board, captures the ’Shoe’s clientele, whom he mixed with back in the 1960s and early 1970s: “Many of the patrons were folks who came from outside the city. They were migrants from rural Canada, northern Ontario, and down east. There were farmers and fishermen, truck drivers and factory workers, coming together from the heartland of a great nation.”

Other patrons were just drifters and society’s outsiders, looking for adventure, escape, or a change of scene. Greg Marquis eloquently captures these characters and their stereotypes in his essay “Confederation’s Casualties: The ‘Maritimer’ as a Problem in 1960s Toronto”: “In the eyes of urban Ontarians, Maritimers had several characteristics. They were fatalistic young drifters who lived off welfare, drank heavily, engaged in violence, listened to country and western music, and broke the law in order to survive.”

Despite Marquis’s assessment, the violent stereotype of these East Coast emigrants did not hold true at the Horseshoe Tavern. Violence was rarely an issue. Everyone came for a good time and respected Starr enough to not cause trouble. So, how did the Horseshoe go from being a restaurant that served some of the best prime rib in Hogtown and was a watering hole for blue-collar factory workers, rounders, and cops in the downtown core to becoming Canada’s top country and western bar, with lineups on Queen Street that stretched for several blocks on Saturday nights?

The evolution was simple.

Starr always put his customers first. And all the Horseshoe’s customers had two things in common: they liked to drink, and they liked to dance.

One afternoon, Jack left his office in the back of the club to check on his customers, as was his habit. As he was walking through the bar, talking to the folks who were there, one of the loyal customers chirped, “Hey, Jack. You should start booking live music here.” To which the owner replied, “Okay. What kind of music do you like?” “Country, of course,” the customer said.

And so country and western music it was.

The genre was certainly not something Mr. Starr and his family listened to at home on the radio. “Jack knew how to bring the music in, but he wasn’t very musical and we all hated country and western music!” recalls his daughter Natalie Clairman, whose family still owns the building. “We never went down there at all.”

But, being a shrewd and smart businessman, Mr. Starr knew satisfying his customers was crucial to running a successful small business. As he once told the Toronto Star, “I didn’t know anything about country music in those days, but I looked around and I figured that, with all the other types of entertainment available in the city, there must be room for a country place.”

The Edison Hotel on Gould Street had a foothold on Toronto’s nascent country scene; later, the Brunswick House on Bloor and the Matador at Dovercourt and College hired country acts. But the Horseshoe would acquire a reputation for booking the best — Nashville’s top talent. (It also became an unwritten rule that if you played the Edison, you didn’t play the Horseshoe, and vice versa.)

So Starr got to work, replacing the kitchen with a stage (in the backroom where the bar is located today) and renovating the space — gradually expanding the available space fivefold by purchasing neighbouring stores. By the time Starr started booking live music, the seating capacity had increased from eighty-seven to five hundred. An assortment of square and round tables with chairs were nestled right up to the stage, which was only slightly raised off the black-and-white checkered tile floor that remains to this day. With this new setup, the performers and audience melded into one.

Bazil Donovan, the bassist for Blue Rodeo, grew up in Toronto’s west end. His parents were regulars at the Horseshoe — one of the many couples who had migrated from the East Coast. His mom was a Cape Bretoner, and his dad was born in Prince Edward Island but grew up in Halifax. Bazil’s dad loved country music, while his mother was more into rock ’n’ roll — Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly. “He watched what became The Band [former members of Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks] at the Concord a lot. My dad went to all of those places. My mom was seventeen when she had me,” Donovan recalls. “They arrived in Toronto in April 1956. My dad was twenty. Needless to say, they were out to explore ‘the big city,’ and the things that mattered to them the most were listening to music and dancing. I remember him bringing me home autographed pictures of some of the people he saw play at the Horseshoe, such as Stonewall Jackson. I didn’t know who the guy was, but he said, ‘Keep this, and someday it will be worth something.’ Of course, I never did.”

Juanita Garron arrived in Toronto in the early 1950s. Like many before her, she, too, quickly fell in love with the country music scene Starr started. This passion for country and western led to a job checking coats at the Horseshoe. From this vantage point, Garron heard the music nightly and met many of the Nashville stars of the day. Starr was so impressed by Garron’s amiable personality, and her good ear, that he expanded her duties over the years — sending her on the road. Garron took scouting trips to Wheeling, West Virginia, and Tennessee to see these legendary musicians and other rising stars at the Grand Ole Opry and other western venues.

Stonewall Jackson, one of the most popular country artists of the 1960s, was a regular at the Horseshoe Tavern.

According to her obituary (Garron passed away on December 22, 2014), in her lifetime she visited this country music shrine eighty-eight times. “She was approachable, awesome, kind, and thoughtful,” recalls Doreen Brown, a country artist and one-time friend of Garron’s. “She loved to talk about country music. She didn’t drink, smoke, or swear, but she was hilarious!” With a great deal of encouragement from the musicians she met, Garron later started singing country and western Bible songs and hymns. Her talent was recognized by the major country and western associations in Ontario and she was well known for her rendition of “One Day at a Time” and for singing Canada’s national anthem at the opening and closing of Ontario’s country and western music associations during their meetings, jamborees, and other events. It’s no surprise to learn that Starr later presented his former coat check girl with a certificate naming her the “Mother of Country Music.”

For more than a decade, tour buses, all with Nashville plates, were a common sight in the vicinity of the Horseshoe Tavern, and they often parked in the back alley. No matter the weather, country music fans lined up hoping to share a few words with their idols and snag an autograph. Usually, the musicians obliged. During intermissions, members of the feature band or the house band would go from table to table selling the headliner’s latest LP. If the show was presented by one of the major country record labels of the day — such as RCA — the artist would set up a booth near the coat check to sign LPs and photographs, and to shake hands with the regulars.

Bob Gardiner, a country music photographer and journalist, was a regular at the Horseshoe throughout the 1960s and early 1970s. When his marriage broke down, he lived in a boxcar for a while on the Canadian National Railway property, but each evening he headed up to the tavern on Queen. The octogenarian recalls a particular fond memory of an interview he conducted for Walter Grealis’s RPM magazine with Grand Ole Opry and Country Music Hall of Fame member Ernest Tubb:

I went down to the Horseshoe in the early afternoon. It wasn’t a great day … it was raining cats and dogs. Ernest let me on to his tour bus that was parked on a side alley in behind the club. We were just getting acquainted before the interview when Ernest looks out the door and sees all these people standing in the rain. He’s dressed in this beautiful Nudie suit and says to me, “Before we get down to business, I have to go out and meet these people. If they are willing to stand out there in the rain, I appreciate that and need to let them know.” After chatting with his fans, Ernest came back in and he looked like a drowned rat. His beautiful Nudie suit was soaked. He went to the back of the bus, changed, got spruced up again, and then we had a nice conversation.

Later that night, Tubb opened his show at the ’Shoe to raucous applause, and began by playing his hit “Thanks a Lot.”

Every weekend, a similar scenario played out. Couples congregated at this country music shrine to worship their musical idols like Tubb, whose career spanned more than four decades and symbolized the heart and soul of Texas honky-tonk. Women with beehives, stretchy pants, and blouses with puffy sleeves came in with cowboys on their arms; the men sported skinny string ties, V-neck sweaters, and padded jackets. Most had pompadours and long sideburns. The women hummed, clapped, and sang along to their favourite songs; the men hooted, hollered, and banged on the tables for one more encore before closing time at 1:00 a.m. On busy weekends, up to thirty staff members would be hustling trays of beer from the bar to the tables throughout the performances. Mickey Andrews, who was in the house band for four years from the late 1960s to the early 1970s, recalls towers of empty beer cases stacked in the corners of the bar by Sunday night.

Charley Pride was another regular at the country shrine on Queen Street. Bob Gardiner knew him well. The photographer used to show up early for all the concerts, head backstage, and hang out with the various artists. He always had his camera bag with him, and often put it in the corner of the dressing room. “I remember one night being there before a show with Charley,” says Gardiner. “After the show, I had to go back to get my bag, and it was gone! I turn and look at Charley sitting in his chair, and he had this big, sheepish grin on his face. I knew he had hid it on me … he was a bit of a joker.”

A feature article in the Toronto Daily Star in March 1964 proclaimed, “Make Way for the Country Sound.” In it, journalist Morris Duff says, “At a time when many other clubs are pushing panic buttons, those featuring country and western are doing business, even when it rains or snows.” The paper had a weekly column, Around the Ranch, with the latest country and western news, and the city even had a magazine dedicated to covering the genre called The Country Gentleman.

During this era, radio also helped get the word out about the Opry stars. Bill Bessie hosted a weekly program on Saturdays between noon and 1:00 p.m. on CBC Radio in which he would interview the Nashville stars who were playing the Horseshoe or the Edison that night. CFGM Radio, based in Richmond Hill, Ontario, also helped spread the country and western gospel. Starting in 1968, the FM station broadcast of country hits was fifty thousand watts strong, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. It was the first Canadian station to program country music exclusively; later, in 1976, the broadcaster even produced a show dedicated to the genre, called Opry North, that mimicked Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry. The popular syndicated show continued until CFGM ended its country music policy in 1990.

Jack Starr with future Country Music Hall of Famer Loretta Lynn in the late 1960s.

As country music grew, the station increased its wattage and expanded its listener base. Alan Fisher was a DJ for CFGM in those years, and he had the chance to chat with many of the Nashville stars when they played in Toronto, frequently at the Horseshoe. He would also introduce them in the evenings as the emcee when the radio station sponsored some of the shows.

“One of the features of the show had me interviewing one of the stars who would be appearing in town that week, either at the Horseshoe Tavern or at the Edison on Yonge or from the Nashville North CTV show,” Fisher recalls in his book God, Sex and Rock ’n’ Roll. “I got to meet and interview a lot of them, including Bill Anderson, Loretta Lynn, George Hamilton IV, Bob Luman, and many more.”

Before Bernie Finkelstein went on to make his mark in the music industry, managing the likes of the Paupers and Bruce Cockburn and founding True North Records, he was just an adolescent with little interest in school and a growing love for anything to do with music. He was also a friend of Fisher’s. In later years Blackie and the Rodeo Kings, another band he managed, was a mainstay at the ’Shoe, but he says his first time walking through those timeless doors as an underage teenager remains his fondest.

I remember going with Al [Fisher] down to the Horseshoe one afternoon when he was a DJ working for CFGM. I had never been in there before, and my first impression was of it being quite glitzy. Ferlin Husky was playing. Anybody who knows anything about country music knows “Wings of a Dove,” which was his big record. That remains even today an unforgettable experience. I’ll never forget that first time at the Horseshoe. For me, the real excitement was all those country-music-loving women in their bouffants. Who knew what mysteries lurked under those wild hairdos?

Ferlin Husky was one of the stars Fisher interviewed. He played the Horseshoe many times, including that memorable first night for Finkelstein in 1969. “Wings of a Dove,” a gospel song, was a number one country hit for him in 1960 and one of his signature songs. The future Country Music Hall of Famer (2010), who went on to sell more than twenty million records, was one of the more popular performers at the venue in the late 1950s and 1960s.

The Horseshoe didn’t just draw residents of Hogtown looking for a hoedown. Many came from the outskirts of Toronto; some drove more than a hundred kilometres to hear that good old country music, and some even flew! Jack Starr told Dick Brown, in a feature piece for The Globe and Mail in 1973, about a time a mother and her daughter flew up on a Friday evening from St. John’s just to catch a performance by Husky, and then jumped on a plane back to Newfoundland on Saturday afternoon.

Country fans could not get enough of the Toronto twang and the dancing that usually accompanied it. After the Horseshoe wound down, shortly after 1:00 a.m., their appetite for more had to be satiated. To keep the party going, Toronto’s first after-hours country and western club, the Golden Guitar, opened in 1964, and then Beatrice Martin, the Horseshoe’s hostess with the mostest for more than a decade, opened her own after-hours club that same year. Aunt Bea’s short-lived Nashville Room on Spadina, south of College, catered to the country music fans’ desire to keep the honky-tonkin’ going long into the wee hours. According to reporter Jack Batten, Aunt Bea had neatly coifed silver-blond hair. She was always smiling, and her smile was contagious. She made friends with everyone she met. In an interview with the Toronto Daily Star, Aunt Bea described how her speakeasy came to be.

Country fans are such a loyal bunch, you know. They can never get enough of their music. And the musicians are the same — they like to keep on playing all night. On weekends, especially, nobody wants to quit after the Horseshoe closes at 1:00 a.m. and for years they all kept saying to me, “Oh, Aunt Bea” — everybody calls me that — “why don’t you start another place for afterwards.” Finally, I did, and now the Nashville Room’s open until four or five in the morning every Saturday and Sunday. And we all have a wonderful time, listening and dancing and talking.

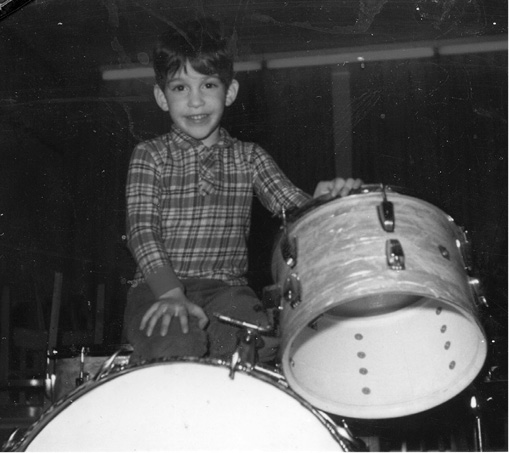

Gary Clairman, Jack Starr’s grandson, pretends to play the drums at Aunt Bea’s after-hours club one Sunday morning.

For a brief period during the Horseshoe’s heyday as a country music mecca, Bea’s Nashville Room, with a capacity of about 250, was packed every weekend night long after last call ended at the ’Shoe. It was so popular that many patrons were turned away at the door.

The Matador, which opened in 1964 and was run by the late Ann Dunn — a single mother of five who, as the story goes, wanted a place that wouldn’t interfere with her parenting duties — lasted a lot longer. The after-hours club quickly found a home as a notorious booze can and hip honky-tonk spot that satisfied the appetites of patrons and musicians alike. These twenty-four-hour party people wanted to carry on the celebrations on the weekends into the wee hours, long after the Horseshoe and the other honky-tonk bars had closed. Many of the artists who’d been booked at the Horseshoe, along with a parade of patrons, headed over to this speakeasy at Dovercourt and College once the ’Shoe had closed down — keeping the conversations and the music going until 5:00 a.m. Cowboy boots were nailed onto the wall behind the stage. Here, only real traditional country music was played. There was a house band at the Matador, but everyone who went there was like one big family. Performers swapped songs and shared the stage. In between sets, everyone went upstairs to mingle, or downstairs, where there was always a high-stakes poker game being played. Barnboard walls marked the turn-of-the-century building that was once a ballroom and dance hall for soldiers on leave during the Great War. Naturally, signs with “Cowgirls” and “Cowboys” indicated the route to the washrooms.

Over the years, patrons had the chance to witness legendary early-morning jam sessions by the likes of Johnny Cash, Johnny Paycheck, and Conway Twitty. In the 1970s, the Matador was also the stompin’ grounds for Stompin’ Tom Connors following his Horseshoe gigs. Later on, Canadian folksinger-songwriters Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen found their way there, as did many other celebrities; Cohen even wrote the song “Closing Time” about the after-hours club. The venue continued to operate until 2006.

Back at the Horseshoe, the entrepreneurial Starr was looking for ways to expand his business. In the early part of the 1970s, with Martin as the hostess, on long weekends throughout the summer bus tours left from the Horseshoe’s door and travelled the white line south to Music City, visiting the sites like the Country Music Hall of Fame and taking in performances at the Grand Ole Opry. Three hundred music lovers would line up for a chance to get a seat on one of seven buses that made these regular pilgrimages to the home of country music. Sometimes, Starr would tag along on these road trips.

Baseball fence at the old Maple Leaf Stadium at Bathurst and Lake Shore, with a banner advertisement for the Horseshoe Tavern from the early 1950s.

During this period, Starr expanded his business to include music publishing. He promoted big packaged shows outside the Horseshoe at places like Maple Leaf Stadium, the old baseball stadium on Lake Shore Boulevard, just south of where the Tip Top Tailors lofts stand today. Starr managed the artists and manufactured and sold their LPs and other merchandise at their shows, since the Nashville acts had a hard time bringing products across the border in those days.

Bill Anderson, a Nashville songwriter who is still playing and recording today at the age of seventy-nine, keeps a special place in his heart for the Horseshoe Tavern. During the 1960s, Whisperin’ Bill — as he was affectionately known for his soft vocal style — was a regular, playing the Horseshoe at least once or twice a year. A Grand Ole Opry member since 1961, Anderson says that at the time the Horseshoe Tavern and the Flame Club in Minneapolis were the only two places in North America where you could play for an extended run. “It was one of those special places where you could sit down and play for one week, and not have to pack up every day,” Anderson recalls. The country crooner would drive up from Nashville with his band (usually five or six strong) to play a week-long residency at Jack Starr’s tavern. Often, they would play a gig somewhere else on the way to Toronto and then another en route back to Tennessee. Starr would put Anderson and his bandmates up at the Lord Simcoe Hotel. “I don’t think I could have afforded that fine a hotel for me and my bandmates,” Anderson jokes. Once located on the northeast corner of King Street and University Avenue, at 150 King Street West, the hotel opened in May 1957 and was closed in 1979, and the building was torn down in 1981.

Anderson remembers the Horseshoe as an intimate venue with a small stage. He always had a fairly big band. “We used to get creative on how to set up on the stage. The fans were right there in front of us and were always really responsive to our music. There was a country music station in town at the time, so they knew all our songs, applauded often, and sang along. The contract was for nightly shows from Wednesday to Saturday that included a matinee. These matinees,” says Anderson, “saw kids come to the shows; they were always a family-friendly affair and a fun atmosphere.”

In June 1965, the Country Music Hall of Famer went into the studio to cut a promising new song he wrote with bandmate Jimmy Gateley called “Bright Lights and Country Music.” Anderson explains how the idea for the song came about:

The … idea came from a fan letter from a woman in London, Ontario, I got while out on the road. We were in Toronto working a little nightclub called the Horseshoe Tavern. We did a matinee on Saturday afternoon and a night show on Saturday night. One of my fans had written me a letter. She said, “I’m going to come to the night show because I like soft lights with my country music.” I read the letter to Jimmy and both our ears perked up and our songwriters’ antennas went up. We wrote almost the entire song in the dressing room at the Horseshoe Tavern.

I told Jimmy, “There is an idea in here somewhere,” but soft lights didn’t feel right.

Throughout their whole set that night, the pair couldn’t get the words from that letter out of their minds. When the show ended, they went down to the dressing room in the basement of the Horseshoe where, after each show, the fans would line up for autographs and pictures with the visiting Nashville musicians, shake hands, and buy records.

“On this night, we told the crowd to wait and be patient for a minute, as we had a song to write. They were very respectful and patient. With the door of our dressing room open, Jimmy and I, with our guitars, sat there, and the song came to life. It’s the only song I ever wrote in front of an audience. We took turns coming up with lines and writing the tune,” recalls Anderson.

Today, Anderson still lives in Music City and plays live every chance he gets. He also recently celebrated the fifty-fifth anniversary of his joining the Grand Ole Opry. “An old man like me doesn’t need to be so busy!” he jokes. I catch up with the legendary country musician, and he tells me how he played the Horseshoe so many times over the years that the gigs all blend together. Still, he says there were a few shows that stood out for him.

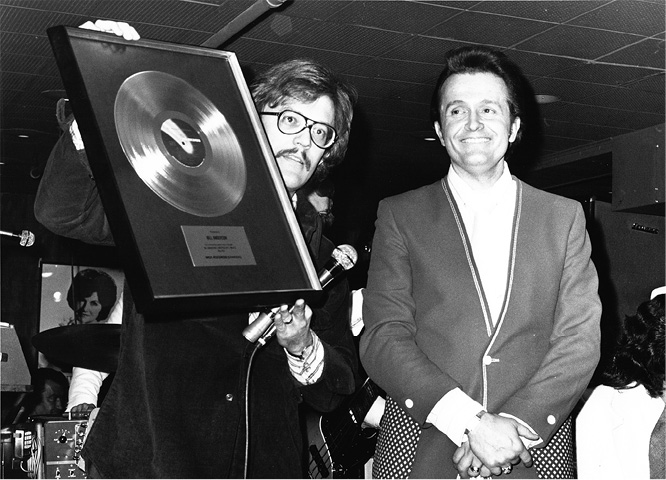

The head of MCA Canada presents Whispering Bill Anderson (right) a gold record for Bill Anderson’s Greatest Hits, onstage at the Horseshoe Tavern in May 1974.

One memorable night he unexpectedly received his first gold record. “I don’t remember the year,” he tells me, “but it was in the late 1960s. I had been recording for Decca Records. Several of the local office staff in Toronto came down to the Horseshoe one night to see my performance. What I didn’t know is they were there to present me with my first gold record. It was for my album Bill Anderson’s Greatest Hits, which had gone gold in Canada. One of the guys from the record company came up on stage in the middle of our set and made the presentation. I still have the photo somewhere, and the framed record still hangs on my wall.”

Like the other country music stars who played at the Horseshoe from the 1950s to the mid-1970s, Anderson recalls Starr as being a cordial and honest host. “He always honoured our contracts,” he says.

The tavern owner and music promoter was also an avid golfer. He once tried to get Anderson to go tee it up with him, but for some reason that Anderson can’t recall, the invitation to play a round together never panned out. Starr did drive Anderson up to CFGM, the country music station in Richmond Hill, for an interview once, though. Whisperin’ Bill said he always enjoyed the candid conversations he had with the Horseshoe’s original owner on those short trips.

In the mid 1960s, Starr hired Dick Nolan and the Blue Valley Boys (Johnny Burke, Roy Penney, and Bunty Petrie) as the Horseshoe’s house band. They would play during the first part of the week, and then back up the Nashville headliners on the weekends.

Nolan was a pioneer of a Newfoundland style of country music, and was just nineteen when he brought that unique East Coast style to Toronto — first to the Drake Hotel, and later to the Horseshoe Tavern. By the time he died in 2005, Nolan had recorded forty albums and sold approximately one million records. He was the first Newfoundlander to have both a gold (fifty thousand units sold) and a platinum record (one hundred thousand units sold), and was also the first musician from The Rock to appear at the Grand Ole Opry. He’s best known for his 1972 hit “Aunt Martha’s Sheep.”

When Nolan migrated to Toronto in 1958, he was set on seeing what the big city could offer. Before landing his first gig playing music, he waited tables at another country bar — the 300 Tavern at College and Spadina.

June Carter Cash and the Carter Family play the bar in the 1960s, when it was known as Nashville North, backed by the house band featuring lead guitarist Roy Penney.

Blue Valley Boy Roy Penney grew up with Nolan in Corner Brook, Newfoundland. The pair had been performing in several of the bars in their hometown before they were even of legal drinking age. Penney says during his stint at the Horseshoe in the mid-1960s, the Nashville musicians took him into their inner circle. He made fast friends with many of them, including the Carter Family, Little Jimmy Dickens, Billy Walker, and Charley Pride. They respected his hard work and dedication.

To prepare for each week’s gigs, Penney would stay up late listening to the latest country and western hits on CFGM radio and capturing them with his trusty tape recorder so that he could play them back and learn the guitar licks. Many nights, if he didn’t go to Aunt Bea’s after-hours club or the Matador, he would drive the stars back to the Executive Hotel, where most of them stayed during their time in Toronto. Sometimes they would invite him up to their rooms and he would go and share a drink and chat about music. One night, Little Jimmy Dickens gave Penney a sneak preview of one of his new songs. It was a silly number called “May the Bird of Paradise Fly Up Your Nose.” Well, that song went on to be a huge hit for Dickens, reaching number one on the country charts and number fifteen on the pop charts. Penney felt privileged to have been able to hear it first. For a good many years, the Horseshoe Tavern was the centre of Penney’s life. Today, it’s where his warmest memories still reside.

Jack Starr (far left) poses next to famed Grand Ole Opry star and hillbilly singer Little Jimmy Dickens.

From 1963 to 1967, New Brunswick native Johnny Burke (née Jean Paul Bourque) played with Penney as the Blue Valley Boys’ bassist. Burke was playing the New Shamrock Hotel at Coxwell and Gerrard when Nolan came to the club to hear him perform one night. After his set, Nolan asked Burke to join the band. The catch: they wanted the guitarist to play bass, which he had never played before. “I told them, ‘I don’t even know how to hold one!’” Burke says. “They replied, ‘We can teach you pretty quick.’” So Burke borrowed his bass player’s instrument and went to the Drake Hotel for an audition. A few fumbled notes surely occurred, but somehow the musician pulled it off. He was a Blue Valley Boy.

The next thing you knew, Starr hired Burke and the rest of the band — luring them away from their regular gig at the Drake by offering them each the union scale of $110 per week. “That was really good money in those days, because before I got into music, I was working in a silkscreen printing shop for forty dollars a week, working ten hours a day, six days a week,” Burke recalls. “At the Horseshoe we did three, and later four, forty-five-minute sets a night, from 9:00 to 1:00, six days a week.”

The Blue Valley Boys had Sundays off, but for the rest of the week they backed every Nashville act who came through town: from legends and Grand Ole Opry mainstays like Bill Anderson, Conway Twitty, Little Jimmy Dickens, Stonewall Jackson, George Hamilton IV, Tex Ritter, and Ferlin Husky to the new breed of burgeoning 1960s outlaw country acts, Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson. Burke remembers when Tex Ritter appeared one Saturday night; the lineup on Queen Street stretched for several blocks — all the way down to Peter Street.

The local country and western fans made the Nashville artists feel right at home in Canada; the Horseshoe was one of the most welcoming venues they played on the touring circuit, which included stops at places like the Golden Nugget in Las Vegas and the Palomino Club in Los Angeles. George Hamilton IV was a regular at the bar; he especially loved Canadians, and playing the Queen Street tavern was always a treat. He sums it up in the liner notes to Canadian Pacific, the 1969 tribute album to his northern neighbour that features covers of songs written by Canadian folksingers such as Gordon Lightfoot and Joni Mitchell:

Toronto is one of the great cities of the world and one of my truly “special places.” (Along with Winston-Salem and Nashville.) It’s becoming quite a booming music center and is even often referred to in country-music circles as the Nashville of the North. Two network Canadian country-music shows originate in Toronto (The Tommy Hunter Show and Carl Smith’s Country Music Hall ) and there are several clubs in the area that feature country music fulltime and a twenty-four-hour a day country music station — CFGM.

Another anecdote from Burke’s four-year ’Shoe run involves Little Jimmy Dickens: “One afternoon Jimmy [Dickens] came in, and the fiddle player was playing a fiddle tune and I was playing bass just with my left hand, and I was hitting the snare drum with my right hand. Little Jimmy said, ‘I like that!’ so I played the whole week with him that way, which was a pain in the ass!”

Dottie West, who, along with Loretta Lynn and Patsy Cline, is considered one of country music’s most influential female artists of all time, also played the Horseshoe. West arrived at the tavern in 1964, bringing with her the top ten hit “Love Is No Excuse” she had just recorded with Jim Reeves (who died tragically later that year in a plane crash). Burke recalls, “[West] asked me to learn Jim Reeves’s part. Every time she came to play the Horseshoe, I did Reeves’s part on that song with Dottie, which was a thrill.”

Another night, the band who was appearing at the Horseshoe (their name escapes Burke all these years later) happened to have their set scheduled right in the middle of a Stanley Cup playoff game. Montreal was playing Toronto. Burke and the Horseshoe house band played a set before the game started, but by the time the headliners were set to start things up, the puck was dropping in the good ol’ hockey game. The crowd protested; they wanted to watch the game. So, naturally, the musicians put down their instruments, sat with the rest of the audience, and watched the Maple Leafs battle the Canadiens on the one little TV that was perched in the corner over the bar. “If you couldn’t see it, you would just wait for the screams,” Burke recalls.

In 1967, Burke left the Blue Valley Boys and formed East Wind; the new band had a couple of appearances at the Horseshoe as the guest of the week in the early 1970s. While he hasn’t played at the Horseshoe since those dying embers of the club’s country music days burned, the East Coast musician hasn’t stopped playing — he still plays with East Wind today. He’s also been inducted into both the Canadian Country Music Hall of Fame and the New Brunswick Country Music Hall of Fame.

Fellow New Brunswick musician Norma Gallant later filled the vacancy Burke left in the ’Shoe’s house band. Gallant had moved to the Big Smoke in the 1960s to pursue a music career, changing her name to Norma Gale — she was yet another travelling musician and East Coast migrant who found a temporary home at Toronto’s Horseshoe Tavern.

Of all the East Coast migrants who found success and called the Horseshoe home, no one left more of a legacy or set more records than Mr. Charles Thomas Connors, better known as “Stompin’ Tom.” “If you ever had to put one thing in a time capsule to explain the Horseshoe, Stompin’ Tom would be the one thing I would put in,” says journalist Peter Goddard. In the next chapter, you will learn how and why this man from Skinners Pond, Prince Edward Island, came to define the next era in the legendary bar’s history.