3

Tom’s Stompin’ Grounds

Come all you big drinkers, and sit yourself down

The Horseshoe Tavern waiters will bring on the rounds

There’s songs to be sung

And stories to tell

Here at the hustlin’

Down at the bustlin’

Here at the Horseshoe Hotel

— Stompin’ Tom Connors, “Horseshoe Hotel Song,” from the gold record Live at the Horseshoe (1971)

Drifter, outsider, larger-than-life, and patriotic to the core — there was no one else like Stompin’ Tom Connors.

Many consider the musician to have been a national treasure. His catchy songs with simple lyrics, which are easy to memorize, are still sung from coast to coast by generations of Canadians. Who doesn’t know the refrains to his timeless tunes such as “Sudbury Saturday Night,” “Bud the Spud,” or “Big Joe Mufferaw,” about everyday characters who embody the spirit of our country? Mark Starowicz captured the essence of Tom’s patriotism in a feature for the Last Post in 1971:

I never thought that nationalism was so deeply ingrained in this country until the first time I saw Connors at the Horseshoe. I’ve seen a packed crowd go wild over a singer before, but I’ve never, never seen so much unrestrained joy and applause as when this rumpled Islander got up and started strumming.

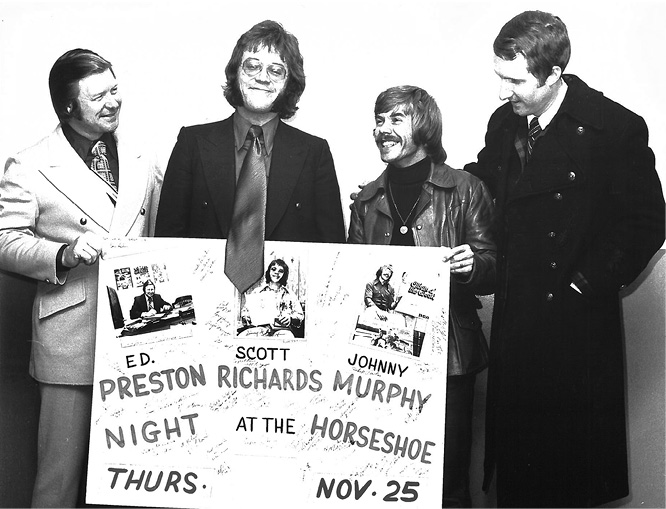

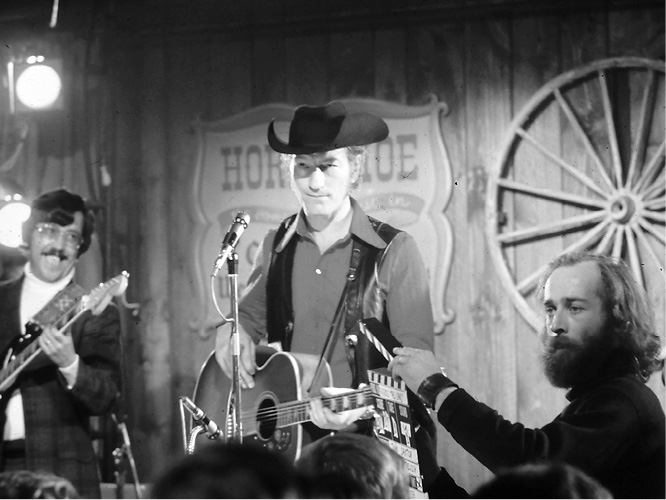

Jack Starr (left) celebrates with Stompin’ Tom Connors on the occasion of the Horseshoe Tavern’s twenty-fifth anniversary in 1972.

As the 1960s started to set, making way for the 1970s, the country singer from Skinners Pond, Prince Edward Island, made up his mind that he wanted to perform at the Horseshoe regularly. So he kept coming in and asking Starr to give him a chance. Again and again he’d get his courage up, only to have it knocked down by Starr. But eventually the young musician’s persistence paid off. Jack Starr saw something others didn’t in the fellow outsider.

Today, Connors’s legacy is as legendary as the tavern itself. You could say, for a while, it became Tom’s bar. “Tom made a big mark in that place,” recalls Johnny Burke.

As this chapter unfolds, it will become clear that those eight words of Burke’s are definitely an understatement. Dick Nolan’s biographer, Wayne Tucker, shares the following anecdote that foreshadows Connors’s lasting legacy:

Willie Nelson played the Horseshoe in the 1960s, backed up by the Nolan-led Blue Valley Boys. Dick was around Willie every night and they raised a few glasses together.

The Blue Valley Boys — circa mid-1960s — who were the house band at the Horseshoe, backing up all the Grand Ole Opry stars. From left: Roy Penney, Bunty Petrie, Dick Nolan, Johnny Burke.

One particular time Dick and Willie were chatting over a beer while another performer who was an unknown at the time was on stage. Dick noticed Willie’s mind was drifting and he kept looking up at the singer. Willie said, “Dick, that guy’s got somethin’ goin’ for him. He’s gonna turn out to be somebody.”

And “somethin’ goin’ for him” he sure did have. Stompin’ Tom went on to set attendance records at the ’Shoe that still stand today, more than forty years on. He recorded a gold record (Live at the Horseshoe) and filmed a feature concert film (Across This Land with Stompin’ Tom Connors) in the bar’s cozy confines, and his record of playing the bar for twenty-five consecutive nights is one that is likely never to be broken. Journalist Peter Goddard, who covered many of the musicians and shows at 370 Queen Street West starting in the early 1970s, provides his take on Tom’s Horseshoe legacy: “If anybody could be said to embody the old and the new, the punk of the Horseshoe, it was Stompin’ Tom. He was louder than any punk band. He came at you like a sledgehammer, which was perfect for the place. He was the real thing.… He also foreshadowed a lot of the punk bands that later tried to emulate him. If the Horseshoe ever reached the nadir of its identity it would be with him.”

Connors’s legacy was solidified at Starr’s tavern. As with many Canadian musicians who came after him, the Horseshoe helped boost his career. “These people really like you, Tom,” Jack Starr told Stompin’ Tom in 1969, one year after Starr gave Connors his first gig. Those genuine words of gratitude came only after Canada’s version of the outlaw country singer — who did not fit the mould of the Grand Ole Opry stars who had graced the stage over the previous decade — had proven his worth and gained the Horseshoe owner’s admiration.

The late 1960s ushered in a new era at the Horseshoe Tavern, and Stompin’ Tom led the charge. Like Starr, Tom was an outsider. Bands had a hard time keeping up with his stompin’ foot and his offbeat rhythms. His songs spoke of blue-collar characters: drifters and dreamers like him. That’s why his stompin’ sounds and often silly sing-a-long lyrics resonated with the Horseshoe’s loyal patrons, since the majority of Starr’s regulars came from Connors’s corner of the world: Atlantic Canada. Beyond his fellow East Coasters, Tom would draw a diverse crowd, a motley mix of beer-drinking regulars — from Toronto Maple Leafs fans, to college students, factory workers, and farmhands, to plainclothes police officers. Tom would sing a corny song filled with off-rhymes about Kirkland Lake, Sudbury, or another rural Ontario town, and the Horseshoe’s patrons would holler, hoot, and pound the tables.

“Tom created a conversation,” recalls Mickey Andrews, who played pedal steel with the Canadian icon for years. “He would always have a song about a town that someone from the audience could relate to. He had a different way of entertaining them, drawing out their animal instincts. They weren’t rowdy, but they were boisterous, and the air was electrifying.”

Stompin’ Tom Connors got his moniker due to his penchant for pounding the floor with his cowboy boot, keeping time. These stomps were so heavy that they started to wear out the carpet and floorboards everywhere he performed. Eventually, Tom came up with the idea to put down a piece of plywood — a stompin’ board, which he bought at Beaver Lumber — down on the stage before each show. As he stomped, dust and chips flew into the air. This was all part of the legend in the making.

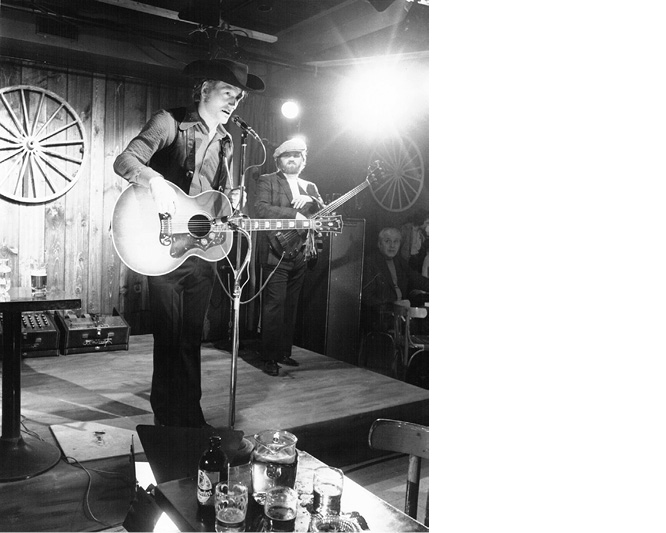

Stompin’ Tom Connors — who still holds the record for the most consecutive nights played at the Horseshoe Tavern — seen here in a still photo from the movie Across This Land.

The country singer from Canada’s smallest province came to the club owners and concert promoters like a thirsty lion, not a shy lamb. Tom was always his own best PR person; the way he landed the gig at the Horseshoe is a perfect example of this dogged determination. Andrews recalls seeing Tom play at an after-hours club before Starr hired him, and thought he was tipping off the club owner to a new act. Not so. Tom had already gathered up his courage and been to see Starr many times, begging for a chance to play that storied stage. In late 1968, Starr finally relented, giving Connors a chance to prove himself by booking him for a one-week stint. It’s something the late musician never forgot. In his memoir Stompin’ Tom and the Connors Tone, the singer devotes an entire chapter, “Landing the Horseshoe,” to Starr’s bar. In it, Connors recalls the seminal moment when he signed his first contract to play the iconic institution on Queen:

On the twenty-eighth or twenty-ninth of November, I got my courage up again and decided to go down to Toronto and try the Horseshoe Tavern, only this time minus the suit. I really didn’t have much faith in landing a job there because the Horseshoe was known all over Canada. Everybody who was a country fan and who landed in Toronto for any reason, either by plane, car, bus or train, for any length of time, sooner or later, wound up paying a visit to the Horseshoe. The owner’s name was Jack Star [sic] and he had kept the place “country” through thick and thin now for over twenty years and the club had a great reputation. There wasn’t hardly a weekend that went by that the place wasn’t packed, due mainly to the fact that he would always bring a big-name act from Nashville, Tennessee, to play Friday and Saturday night. When Jack finally arrived on the scene I was pleasantly surprised to find that he was a very quiet, congenial man, even though he had the demeanour of a person who knew his business very well. He made me feel at ease and I began telling him what I had done, where I had been up until now, and just how much I wanted a chance to play his club to see how well I could fare. “Well,” he said, “I’m trying out a new house band next week and if you want to come in and see if they can back you up, I’ll give you the opportunity to see what you can do. Bring your contract in before you start on Monday night and I’ll sign you on for a week.

Tom could not believe his ears. That weekend he went back to where he was staying, and that’s all he could talk about with the owners of the house. On Monday, at around four o’clock in the afternoon, he returned to the Horseshoe and just sat there for the next five hours, until his set time at 9:00 p.m. The only interruption to his thoughts came when Starr stopped by his table and asked him for his union contract. After signing it, Starr shook Connors’s hand and said, “You must really want to play here. I’ve been watching you sit there for the last three or four hours, and I don’t think you took your eyes off the stage once.”

That first gig established the tone and set up Tom for his legendary run at the Horseshoe. Tom was relaxed and ready to give it his best shot. “This gig is going to be a snap for me,” he said, “because every place [I] had ever played up until now, [I] had to carry the whole ball all by [myself].” At other bars, Tom was used to starting at 8:00 p.m. instead of 9:00, and he would do four one-hour sets, with only a fifteen-minute break after each hour, before finishing up at 1:00 a.m. At the ’Shoe, he had to play for only an hour and a half during the whole night.

From the time he dropped his famed stompin’ board on the stage and started to sing, he never looked back. Initially, the boys in the house band found it difficult to keep time with Tom, but as soon as they realized his left heel was always coming down on the offbeat, rather than on the downbeat, they quickly grasped what was going on and started to have almost as much fun watching Tom as the audience did. Connors recalls the reaction on that memorable night: “Even the waiters who had been there for twenty years or more were seen from time to time to just be standing there wondering how in the hell could I stand on one foot for so long and go through the antics I did without falling down.”

In between sets, Tom used the time to do what he did best: public relations — consuming a beer at every table, talking to everyone, and selling his records. By the time the night was over, the musician knew every patron by his or her first name; he then stood by the front door, as if he owned the place, thanking them for coming as they left.

By the end of that first week, word had spread along Queen Street and out into the suburbs. Many people came back to see the show on the weekend and brought their friends. Even though the place still wasn’t packed, Stompin’ Tom managed to get another contract signed with Starr — this time not just for one week, but for three.

For Tom, the chance Starr gave him that November and the faith he placed in him was the best gift he ever received. It’s also one he never forgot. “This all took place about the first week of December in 1968,” he recalls in his memoir. “It gave me the extra money I needed to buy Christmas presents for everybody, but the best Christmas present of all was the one I got. And that was my opportunity to play the Horseshoe Tavern in Toronto for the first time.”

The following February, Tom returned to the Horseshoe, backed by a new house band. Apparently Jack Starr was trying out different bands at that time, trying to find one he was happy to hire full-time. That return to the ’Shoe for Tom was not what he had expected, because he didn’t click with this band as he had with the one he had played with the previous November. Connors reflects on this lack of chemistry:

From my very first night on the stage, I could see the guys in this band were either very jealous of me, or they just didn’t appreciate what I was trying to do. I was singing my own songs, of course, and doing absolutely nothing from the current hit parade. This they didn’t seem to understand. For the whole week they didn’t talk to me and just kept screwing up my songs whenever they could in an effort to discourage me and get me to quit. During each break they’d just go to a back table and sit by themselves while I was always associating with the people. And practically every table I went to, they’d tell me how the band kept sneering, laughing and pointing at me behind my back in an effort to get the audience to do the same thing. Unfortunately for them, their little scheme wasn’t working. I just ignored the whole thing, did the best I could under the circumstances, and kept right on with my public relations.

At the end of Saturday’s matinee, Starr called Tom into his office and asked him how he liked the new band and how they were getting along. Connors, ever diplomatic when he needed to be, knowing how tough it sometimes was for musicians to get work and not wanting to lessen their chances of keeping their jobs in any way, told Starr that while they did seem to be a bit standoffish, it was probably due to shyness, and while they hadn’t quite caught on to his music yet, they would probably get used to him and do a lot better job next week.

Starr wasn’t fooled. He knew the truth. The tavern owner replied, “Well, Tom, that’s all very decent of you, but you don’t have to give me any crap. These guys have been into my office three times this week trying to get me to let you go. They said you can’t keep steady rhythm, you’re annoying the customers, and your foot is driving them crazy.”

As Starr sat staring at him from behind his desk, Tom tried to defend himself against these allegations. Before long, Jack interrupted him and eased his mind: “Don’t worry yourself about it. I’ve been keeping tabs on the whole situation, and after tonight, you won’t have to work with these guys anymore. I’m keeping you and letting them go.”

Starr then asked Tom how he had gotten along with the previous band he had played with. Tom told Jack he thought they were excellent and that they had all gotten along very well. The good news was that Starr still had that band on standby, and he assured Tom they’d be backing him up the following week and any time he played the Horseshoe thereafter. Then Starr flashed his infectious smile, got up from his desk, shook Tom’s hand, and said, “These people really like you, Tom. Now go and get ’em.”

That band that Tom played with when he returned to the ’Shoe the following Monday had just seen Clint Eastwood’s latest western The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and decided it was a perfect moniker for their trio: Cape Bretoners Mickey Andrews on pedal steel and bassist Randy MacDonald, along with Newfoundlander Gerry Hall on lead guitar. These three musicians were the Horseshoe’s regular house band up until the mid 1970s, shortly before Starr retired from the business in 1976.

In those days, the Horseshoe could seat between 300 and 350 people. By Tom’s third week of regular gigs, the place was packed even before the Nashville guests arrived on Saturday night. Most of the customers were from Newfoundland or the Maritimes, but Tom started to draw lots of patrons from all over Ontario and from western Canada. Tom continued his public relations each and every night. As well as stopping to chat at every table, he would often hold short conversations with patrons from the stage, especially if he hadn’t seen them there before. It was all part of his attempt to break down any barriers that might have existed between artist and audience, creating a familial atmosphere that still exists today at the tavern. Connors would introduce these newbies to the people sitting at the next table, and before you knew it they were pulling their tables together and acting as if they had known each other all their lives. As Tom says in his memoir, “This encouraged people to be friendlier toward one another and made them feel like we were all just one big happy family. This also made the jobs of the waiters much easier and reduced the incidents of trouble to practically nil.”

In the second week of May 1969, Tom was back at the Horseshoe for another five-week stint. This run eventually doubled, becoming ten. His legend was growing. Ever the PR man, Tom did his part. At each show before the band took the stage, he would place two or three free books of matches at each table as an added courtesy. As it was too expensive to have his name printed on the outside of the covers, he had a rubber stamp made and gave the kids of the family where he was living at the time a few bucks to stamp them all. The design on the stamp was the same as the picture of the guitar on the sides of his truck. The words read “Hometown Songs by Stompin’ Tom.”

“Altogether I must have doled out about nine or ten thousand books of matches during the full ten weeks I was there,” Tom recalls in his memoir. “They not only provided a convenience, but a lot of people just took them home for souvenirs. This was also another method of promoting myself in a rather inexpensive way.”

Mickey Andrews, Tom’s long-time pedal steel player, recalls another way Tom promoted himself. “One of biggest things Tom did [and] he didn’t even tell us, is he spent all his money on these big billboards around Toronto that would say Help Stamp Out Stompin’ Tom. You didn’t know how to take it. I eventually found out it cost him seven hundred dollars for each one of these ads, but it created a big thing about him because they wouldn’t play him on the radio … no matter how hard he tried in those days, he couldn’t get airplay. They wanted their music to sound like what it sounded like in Nashville.”

Radio play obviously didn’t matter to this new generation of Horseshoe patrons, who couldn’t care less whether Tom sounded like he came from the Grand Ole Opry. By the end of Tom’s third week at the ’Shoe, the tavern was beginning to be just as packed on the weeknights as it was on the weekends. This was when Jack Starr approached the singer and asked what other booking commitments he had lined up when his current five weeks were done at the Horseshoe. He said he was prepared to double Tom’s wages and that the musician could stay as long as he wanted. That meant Connors would be making twice as much working for Starr as he would anywhere else. The decision was easy. Tom cancelled a couple of smaller venues and ended up working for Jack for an additional five weeks. This stretch of ten straight weeks for a single featured performer and twenty-five consecutive nights in a row became the official record of endurance that still stands today. Eventually, he got bigger than the Nashville acts because he drew a bigger crowd, not because he had more hit songs. Two other records Tom still holds from the old Horseshoe are for the most patrons and the biggest turnover in any one week, and the most patrons and biggest turnover in any one Saturday. Stonewall Jackson previously held the last record, for Saturdays. The North Carolinian honky-tonker, whose 1959 million-selling hit “Waterloo” kicked off a successful career that lasted for more than a decade, was a regular fixture on the Opry — and at the ’Shoe — during the 1960s. For those wondering, his ancestry does draw a line back to the famous Confederate Civil War general of the same name. The night Tom broke Jackson’s record, he was performing with The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and people were lined up three and four deep, halfway down the block.

It was at the Horseshoe where Tom met a young man from Canadian Music Sales Corporation. He listened to Tom’s songs, liked what he heard, and invited the young musician to join him for a beer. The man was Jury Krytiuk, from Melfort, Saskatchewan, and he had recently been appointed head of CMS’s small record label Dominion Records. A deal was inked. By 1972, Tom had recorded a number of albums for the Dominion label, including a box set called Stompin’ Tom Connors Sings 60 Old Time Favourites, containing five LPs. By now, songs like “Bud the Spud,” and “Sudbury Saturday Night” were synonymous with Stompin’ Tom; everybody knew those songs.

Steve Fruitman was one of those early Connors converts. When he was growing up in Timmins, Ontario, Steve used to listen to Tom’s daily radio program Live from the Skyway Room at the Maple Leaf Hotel over CKGB. Tom became somewhat of a hero to Steve. After he left Timmins, Steve lost track of Connors’s career until one day, after watching Hockey Night in Canada (which used to end when the game was over, and then CBC would switch to the program already in progress), he caught an episode of Countrytime with Vic Mullen from Halifax, Nova Scotia. He explains:

I wasn’t really into country music back then, in 1968, but I kind of liked it. It was basically the only music we had to listen to up north because “our music,” rock music, could only be heard late at night during the Hilltop Rendezvous program on the French station, CFCL. So out comes this special guest star dressed in a black leather vest, big cowboy boots and a hat and a board to beat his heel into and he sings, “Twang twang, a diddle dang a diddle danga — twang twanga diddle dang another dang twang,” and I said, “That’s the guy from Timmins!”

After moving to Toronto, the teenaged Steve was a regular at the Horseshoe, singing along with the rest of the tavern’s faithful to all of Tom’s songs about characters and places he’d seen in his rambles following the white line. Fruitman, being underage, had been sneaking into the Horseshoe as an eighteen-year-old. When he turned nineteen, the Ontario provincial government of Bill Davis lowered the drinking age from twenty-one to eighteen. He recalls those unforgettable nights: “I’d go to the ’Shoe with my school friends, get a good seat, which was a difficult thing to do even on a weeknight, and get right into it. I purchased my first Stompin’ Tom album, Bud the Spud, at the Horseshoe and got Tom to stomp on the cover (having removed the record first). For a kid into The Who, early Led Zeppelin, and stuff like that, this was rather different indeed.”

Flash ahead to December 1972: Tom and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly returned to the Horseshoe. This time, it was for a very special occasion; it had been twenty-five years since Jack Starr had opened his storied tavern. The house that Jack built had grown from a beer and whisky bar, known for its roast beef dinners, to the top country and western venue in the country. It was time to celebrate this milestone, and of course Stompin’ Tom figured into the party. Along with banners flying and hundreds of patrons coming and going all week, wishing the Tavern well, Stompin’ Tom sang the “Horseshoe Hotel Song” several times every night. This was one of the songs included on the Live at the Horseshoe album he had recorded in the bar the previous year. “It was sure getting a workout on an occasion as special as this,” Tom recalled in his memoir Stompin’ Tom and the Connors Tone.

On the Saturday night of the week-long celebration, the place was hopping. The stage was decorated with wreaths and flowers, and Jack went up to receive some well-deserved accolades, take a few pictures, and give a speech. Jack regaled the patrons with stories of the Horseshoe’s humble beginnings, including how he’d missed by only one day obtaining the very first liquor licence ever awarded in Toronto. Starr also reminisced about the good times and some of the bad, and name-dropped a few of the great country stars that had performed on the Horseshoe stage. Then, out of nowhere, at least according to Stompin’ Tom, Starr came out with this proclamation: “Ladies and gentlemen, of all the great entertainers that ever played on this stage, the one that jingled my till the most, the one who broke all previous attendance records and set new ones, the guy who came from nowhere and surprised all of us, and the guy we love because he sings all those songs that make us proud to be Canadian, is none other than this young man standing right here: Stompin’ Tom Connors.”

You would think that after such a remark the crowd would go crazy and take the roof off the place. Well, they did. Tom waved and took a bow, and while he was acknowledging his fans Jack reached into a box he was carrying and pulled out a framed gold record for his Live at the Horseshoe album, passing it to the singer, who was still stunned. “This is one you never expected, Tom, and all the gang from Dominion Records and Boot Records asked me if I’d present it to you, and I’m more than happy to do so,” said Starr. “And whatever you do, Tom, just keep on stompin’.”

No sooner had Starr uttered the word “stompin’” than everyone in the Horseshoe started to do just that. As Tom tried to say thank you to everyone who had bought the record and helped to make the gold album possible, several people dumped some pretty stiff drinks into his water jug that he usually kept on stage, and some of it spilled into the flowers. The press took a couple of pictures of Starr and Stompin’ Tom with the gold album propped up in front of them, and afterward the pair answered a few questions, then left the stage.

Later, after another short set, Stompin’ Tom and Starr wished everybody a merry Christmas. Everyone in the Horseshoe Tavern raised their glasses, gave a toast to their host and their hometown musical hero, and drank up. With that, another chapter in the tavern’s history closed. What would the next twenty-five years hold in store? More outsiders like Starr and Connors — all fuelled by the same passion for the music and for keeping Starr’s bar alive for another generation to enjoy and discover.

In 1973, Tom left one more mark on the Horseshoe Tavern before bidding goodbye to this phase of his career. The film Across This Land with Stompin’ Tom Connors, directed by John Saxton and featuring a young University of Toronto student named David Cronenberg as an assistant production manager, stands as a time capsule. The film, produced and distributed by Montreal schlock studio Cinépix, captures the quintessential Canadian country singer at his best, in the place where he first found success. The PR team Cinépix used to generate awareness and excitement for the movie came up with the following unique selling proposition: There’s a bit of country in all of us, just waitin’ to bust loose. The feature-length music documentary was filmed mostly at the ’Shoe. This wasn’t Tom’s first foray into film, having made his screen debut the previous year in This Is Stompin’ Tom, a short film that wove interview segments into performance footage.

Stompin’ Tom Connors pictured in the movie Across This Land, which was filmed at the Horseshoe Tavern in 1974.

In Across This Land, cowboys and cowgirls sit at tables that crowd the stage. They swig beer, hoot and holler, and stomp along to every song. Tom is at his storytelling best, regaling the audience with the inspiration behind each song. Many guests join Tom on the stage, which features a prominent wagon wheel and artwork designed by amateur artist John Anthony Cullen that reads “The Horseshoe Tavern: The Home of Country Music.” The film kicks things off with a rousing version of “Sudbury Saturday Night” before Connors spends the next ninety minutes telling Newfie jokes and belting out some of his biggest hits, including “Bud the Spud,” “Big Joe Mufferaw,” and “Rubberhead,” as well as parodies of Nashville standards like “Green, Green Grass of Home” and “Muleskinner Blues” (all of which he later released as a live double LP on his own Boot Records). Occasionally, the set list is broken up by guest performances by the likes of Kent Brockwell, Sharon Lowness, Chris Scott, Bobby Lalonde, and Joey Tardif. As each performs, Tom leaves the stage, joins a table of patrons in the front row, and has a couple of beers with his fans.

In 1961, Michael T. Wall arrived in Toronto from Corner Brook, Newfoundland. Like Stompin’ Tom and many fellow Maritimers, Wall came to the Big Smoke looking for work. Before finding success as a country music singer, songwriter, and musician, he worked at a variety of odd jobs, including picking tobacco in Concord, Ontario. “I had a dream to promote my province to the world, and I have done that,” Wall says. He certainly has achieved that dream. He’s promoted Newfoundland from Australia to Asia and all parts in between over the past fifty years. He admits it’s been a bumpy road at times, but says if you love it, it’s important, and the one constant in his life is that he’s always loved country music. Johnny Cash was Wall’s hero: “When I first heard him in 1956, I said that’s what I want to do.”

Today, people refer to Wall as “ageless Michael T.” At seventy-eight, the Canadian Country Music Hall of Fame member continues to bring his unique brand of country music to the world. The first time Wall performed at the Horseshoe was in 1968. Later, he became the singing host at the Molly and Me Tavern and Nightclub at Bloor and Lansdowne. “The place was jam-packed every weekend,” Wall recalls. “I was there for eight and a half years as the host. Sometimes some Nashville stars like Charley Pride would come to watch my show.”

“For a long time, I would sneak in the back door of the Horseshoe to see all the Nashville stars,” Wall recalls. “One night Jack [Starr] caught me and said, ‘You go around front and pay like everybody else.’ So, I did from then on.”

Charley Pride, RCA Victor’s “Pride of Country Music,” holds court and signs autographs at the Horseshoe Tavern’s coat check during his first Canadian visit in 1967.

Once Starr found out Wall could also play and sing, he booked the Newfoundlander. “Jack booked people whom he knew would draw,” Wall says. “He knew I would draw because the Newfoundlanders would come out in busloads to support me. The Maritimers supported me from day one, and they are still supporting me. They wanted to hear a little bit of Newfoundland in Toronto.”

If you got a chance to sing at the Horseshoe Tavern, says Wall, it was special, since Mr. Starr booked only the best entertainers from both sides of the border: “I was privileged to appear there many times, singing my own brand of Canadian country music.”

Besides playing the Horseshoe, Wall was privileged to meet and rub shoulders with Nashville stars like Bill Anderson, Little Jimmy Dickens, Tommy Hunter, Tommy Cash (Johnny’s younger brother), the Carter Family, the Stoneman Family, Skeets McDonald, and bluegrass legend Jimmy Martin.

Born in 1939 in Trout River, Newfoundland, Roy Payne never knew his father. All he knew was that his dad played the fiddle, so there must have been some musical gene in there somewhere. Raised by his grandmother, Payne later learned his real mother was someone he had always thought was his sister. With no parental figure to guide him, Payne left home and school early, hitting the road. First, he was trained as a chainsaw mechanic; then, at seventeen, after a night fuelled by booze, Payne joined the army — spending a dozen years as a soldier, serving with peacekeeping forces in Egypt and Cypress. His final stop was at Canadian Forces Base Borden in Barrie, Ontario, where he was discharged. While serving his country, in his limited free time Payne wrote songs for fun. After leaving the army, he got a job as a chauffeur to Member of Provincial Parliament Darcy McKeough. Riding around in what he dubbed “the big Chrysler,” he wrote a ton of songs. Payne once claimed to a reporter that he had written about 2,600 songs over the course of fifteen years.

Like Michael T. Wall, even before landing a regular gig at Starr’s bar, Payne frequented the Horseshoe. While he was in the army, on his days off he would visit the tavern on his weekend leaves to watch Dick Nolan and his band perform. Later, he attended the matinees on Saturdays to sing a song or two. From watching the house band and sitting in with them, before he knew it, Payne’s name, too, was in lights and posters on Queen Street. Though Payne had little professional experience and very few shows under his belt, for some reason Starr, as he did with Stompin’ Tom, took a chance on Payne, giving him a featured booking. There was something in the way the young man sang and played that Starr knew would resonate with his patrons, especially those from the East Coast. Before he knew it, Payne was headlining the hallowed bar as the leader of the Horseshoe’s house band, which included Terry Hall, Marie Battam, Randy McDonald, and Mickey Andrews, who had played pedal steel for Stompin’ Tom for many years.

For nearly five years in the 1970s Payne would play with the band for seven-week stints, head out on the road for a while, and then come back and play the tavern again. Payne remained friends with Dick Nolan and collaborated with him on occasion; he wrote the liner notes and title song to Nolan’s 1974 album Happy Anniversary Newfoundland.

Payne’s best-known hit was “Goofy Newfie,” at one time the most requested song on CFGM. The album went on to sell close to five hundred thousand copies. Payne wrote this song — his first ever recording — at the Horseshoe, bragging he penned the composition in less than five minutes.

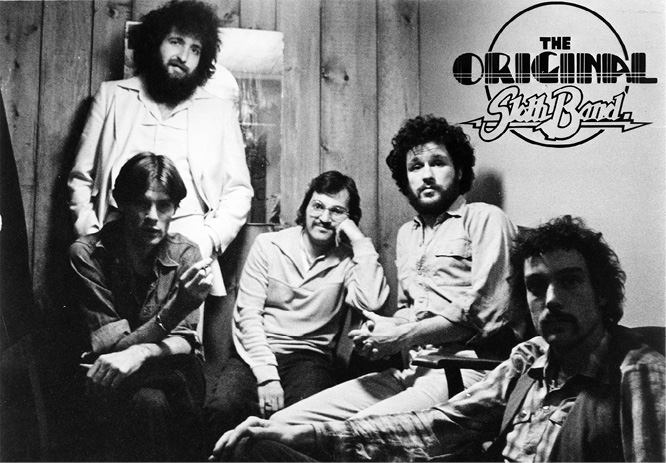

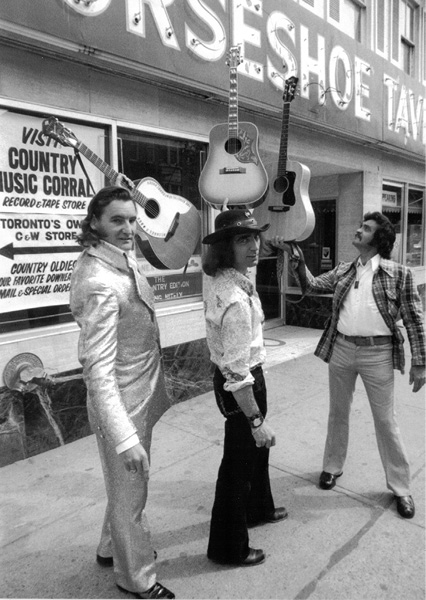

Michael T. Wall, “The Singing Newfoundlander,” with fellow Newfies Roy Payne and Reg Watkins — all of whom played the Horseshoe Tavern many times in the early to mid-1970s.

Starr was impressed with Payne’s blue-collar poetry and ended up signing Payne to a contract, paying the songwriter approximately five hundred dollars. According to Payne, several months later Starr sold this contract to RCA Records for a lot more money. It’s something the musician never forgot. While he was grateful to Jack for taking a chance on him, he felt a little cheated by this business deal. Payne described this situation to John Gavin: “He just signed me to negotiate a contract with RCA and he had all the money in the world. I’ll never forget that and they say he is dead now. I wonder did he take it all with him. I always had a saying that I acquired years ago, that I believe in: I saw a lot of things, but I never seen a Brinks Truck chase a hearse, that’s true, so you can’t take it with you.”

Budgeting was not Payne’s forte. He certainly lived life with the credo “Spend today, for tomorrow you may die.” The following quote, as told to Blaik Kirby of the Globe and Mail in June 1974, sums up Payne’s philosophy when it came to dollar bills:

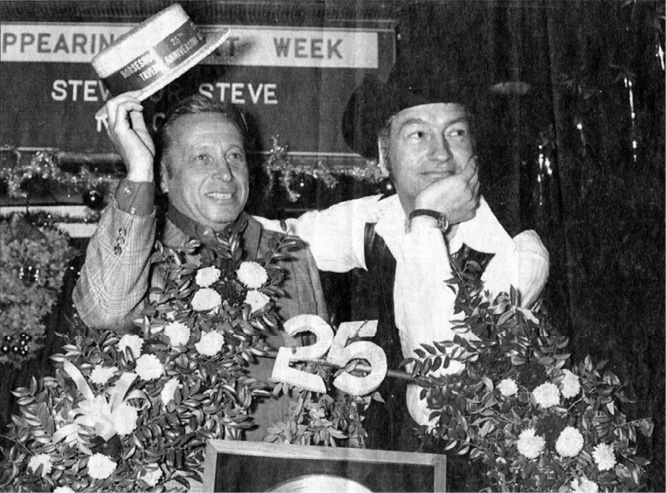

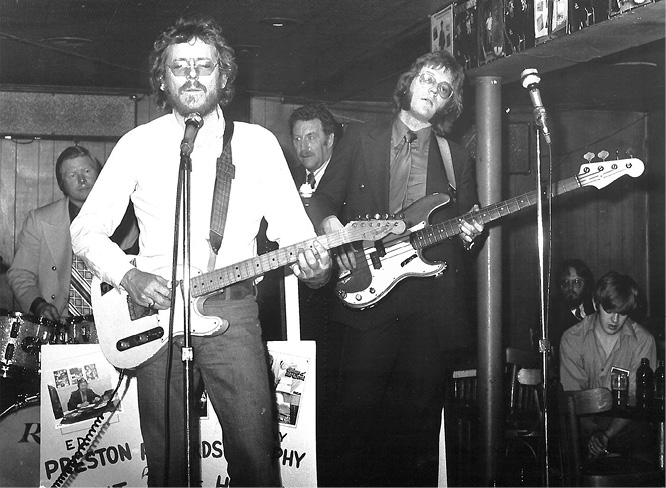

Gordon Lightfoot (left) makes a surprise appearance at the Horseshoe Tavern on Ed Preston night, honouring RCA Victor’s promo team, in the late 1960s.