CHAPTER 11

THINK DIFFERENT

10 PRACTICAL LESSONS FROM 150,000 BRAIN SCANS

No one really wants to see a psychiatrist. No one really wants to be labeled as defective or abnormal. But everyone wants a better brain. What if mental health was really brain health?

DANIEL AMEN

Apple’s iconic “Think Different” commercial is my all-time favorite. The slogan was widely considered a response to IBM’s slogan “Think.” The Apple advertisement ran from 1997 to 2002, at the height of the criticism of the brain imaging work we do at Amen Clinics. It was a stressful time for us. Whenever the “Think Different” commercial would air, I would become emotional, as it described my professional journey and made me feel that I wasn’t the only crazy person trying to change a small part of the world. I can still hear Richard Dreyfuss’s smooth voice saying,

Here’s to the crazy ones.

The misfits.

The rebels.

The troublemakers.

The round pegs in the square holes.

The ones who see things differently.

They’re not fond of rules.

And they have no respect for the status quo.

You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them.

About the only thing you can’t do is ignore them.

Because they change things.

They push the human race forward.

And while some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius.

Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world, are the ones who do.

Now, nearly 30 years after we first began our brain imaging work, we have built the world’s largest database of functional brain imaging scans related to behavior. The SPECT scans have taught us and our patients so many important lessons. In this chapter I will provide you with our top 10 lessons, which can help you feel better fast and dramatically change your life.

TOP 10 LESSONS FROM SPECT SCANS

Lesson #1: Current psychiatric diagnostic models are outdated because they don’t assess the brain.

It’s much harder to fix something if you don’t know what is going wrong.

THOMAS INSEL, MD, FORMER DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF MENTAL HEALTH

Today, the typical way most people are diagnosed and treated for mental health issues is by going to a professional and telling him or her their symptoms. The doctor or therapist listens, examines them, looks for symptom clusters, and then diagnoses and treats them. Patients may say, “I’m depressed,” for example, and the doctor will look at them and then give them a diagnosis with the same name —depression. Treatment is typically an antidepressant medication.

If you are anxious, you usually get an “anxiety disorder” diagnosis and end up with a prescription for an antianxiety medication. Many people with attentional problems end up with a diagnosis called attention deficit disorder or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and are prescribed a stimulant medication, such as Ritalin or Adderall. My favorite example of this phenomenon is the diagnosis for people who have temper problems and explode intermittently. They often get a diagnosis called intermittent explosive disorder, or IED. The acronym is ironic, calling to mind an improvised explosive device, and these patients often wind up in anger management classes or on any number of medications.

CURRENT PSYCHIATRIC DIAGNOSTIC MODEL

SYMPTOMS |

DIAGNOSIS |

TREATMENT |

Depression |

Depression |

Antidepressants |

Anxiety |

Anxiety disorder |

Anti-anxiety medications |

Attentional problems |

ADD or ADHD |

Stimulants |

Intermittent explosions, anger |

Intermittent explosive disorder (IED) |

Anger management classes or medications |

This is very similar to the way Abraham Lincoln was diagnosed with melancholy (depression) back in 1840. He told his physician, Anson Henry, his symptoms, which were consistent with depression; Dr. Henry listened to Lincoln recounting his symptoms, examined him, looked for symptom clusters, and then diagnosed Lincoln and started treatment. That was 178 years ago, but it remains the mainstay of diagnosis today —identifying symptom clusters without any information on how the brain works. Psychiatrists are the only medical specialists who virtually never look at the organ they treat. Cardiologists look, neurologists look, gastroenterologists look, orthopedists look. Psychiatrists guess.

There is a better way.

Lesson #2: Psychiatric diagnoses are not single or simple disorders; they all have multiple types, and each requires its own treatment.

This was one of the earliest lessons SPECT taught us. Giving someone the diagnosis of depression is like giving him or her the diagnosis of chest pain. No doctor would do that because it doesn’t identify the cause of the pain or what to do for it. Consider with me: What can cause chest pain? Heart attacks, heart arrhythmias, pneumonia, grief, anxiety, chest-wall trauma, gas, and ulcers, just to name a few. Likewise, what can cause depression? Loss, grief, low thyroid, brain infections, brain trauma, a brain that works too hard, or a brain that does not work hard enough. Do you think all of these will respond to the same treatment? Of course not.

In my past writings I have described seven brain types associated with anxiety and depression, seven types of ADD, six types of addicts, five types of overeaters, and even three types associated with violence. No one treatment will work for everyone who is depressed, anxious, inattentive, addicted, overweight, or aggressive. They all have different brain types. Looking at the brain helps us develop a more complete understanding of our patients’ problems and more personalized, targeted treatment.

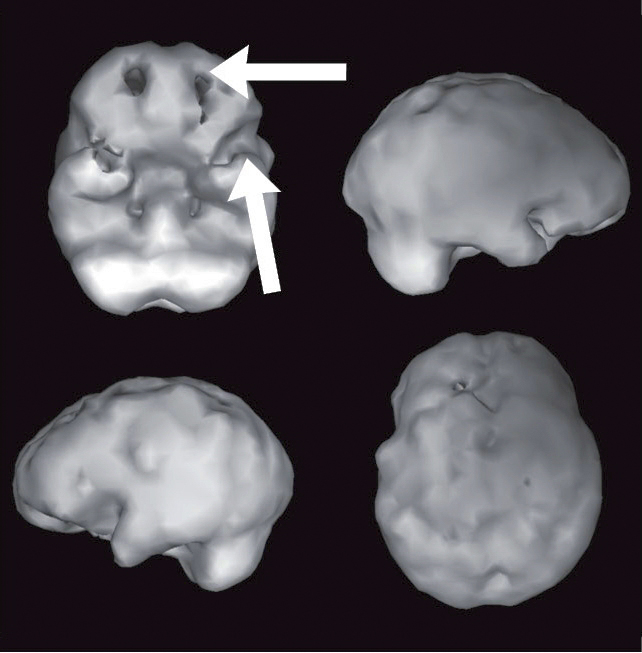

Often when psychiatrists or psychologists come to our office for a tour, I will start by showing them a set of healthy SPECT scans. Then I will show them scans from two 15-year-old multiple murderers.

In May 1998, Kip shot and killed his father and mother. The next day he went to his high school and shot 27 more people, killing 2. Kip had seen several psychiatrists and had taken psychiatric medications that were not helpful. As part of his trial, he had been scanned, and his scan showed overall severely decreased blood flow to his brain, especially in his prefrontal cortex (PFC) and temporal lobes. It was one of the worst scans of a 15-year-old I have ever seen. The damage on his scan was likely from a brain infection, loss of oxygen, or some form of toxic exposure in the past.

Compare Kip to Peter, who killed his mother and eight-year-old sister with a baseball bat for no apparent reason. His scan showed overall increased activity, especially in the area of the anterior cingulate gyrus (ACG), which caused him to get stuck on negative thoughts.

Here are two boys who have the same clinical presentation —multiple murders —but radically different brain patterns. One shows overall low activity; the other overall high activity. Do you think they will respond to the same treatment? Of course not. But how would you know what to do unless you actually looked at their brains? Kip needed a psychiatrist or other physician to find the cause of his damaged brain, then rehabilitate it; Peter needed his doctor to help calm his brain so it did not hijack his behavior.

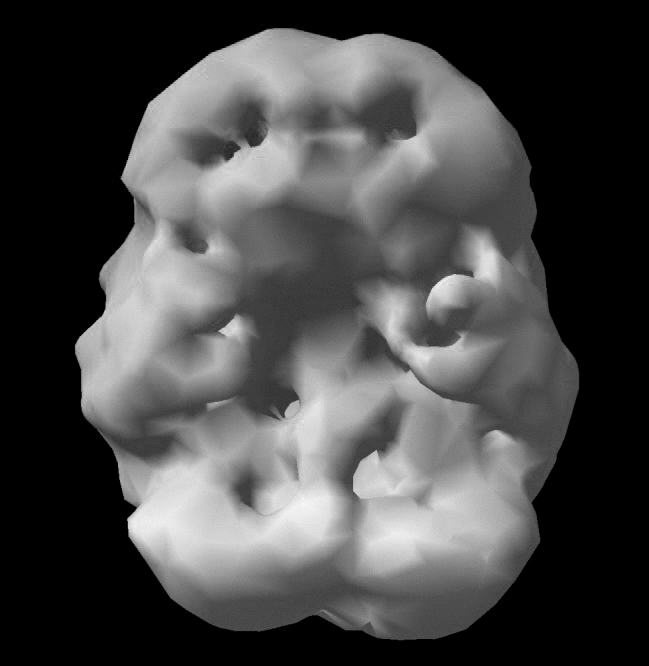

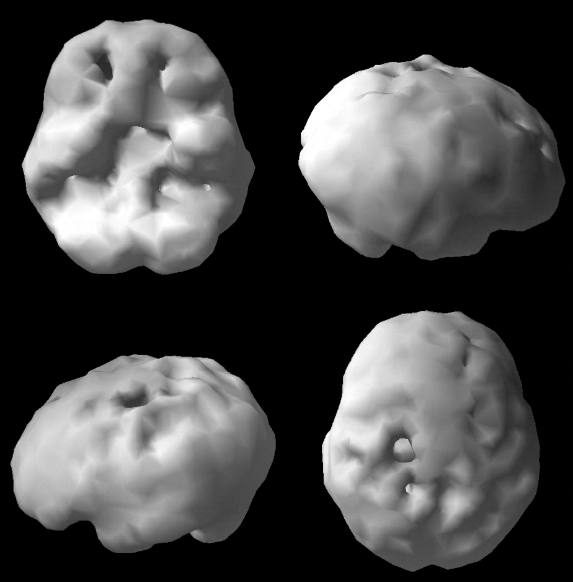

KIP (SURFACE)

Overall low surface activity

PETER (SURFACE)

Healthy surface activity

KIP (ACTIVE)

Overall low activity

PETER (ACTIVE)

Overall high activity

Lesson #3: Looking at the brain decreases stigma, increases compliance with treatment, and completely changes the discussion around mental health.

In 1980 when I told my father I wanted to be a psychiatrist, he asked me why I didn’t want to be a real doctor. Why did I want to be a nut doctor and hang out with nuts all day long? It hurt my feelings then, but 38 years later I understand why he had that reaction. When psychiatrists don’t have hard biological data to help them make their diagnoses, many people do not take them seriously. Unfortunately, that leaves a huge emotional hole for patients, who often feel belittled or defective if they have to seek help for a “mental” illness.

Imaging completely changes the discussion around mental health. Quite frankly, few people really want to see a psychiatrist. My wife almost canceled her first date with me when she found out I was a psychiatrist. No one wants to be labeled as defective, crazy, or abnormal, but everyone wants a better brain. What if mental health were really brain health? Scans have taught our patients that lesson over and over.

One of the reasons I fell in love with SPECT was that it immediately decreased stigma for patients. After seeing their scans, they viewed their problems as medical, not moral. This decreased the sense of shame and guilt that is often associated with having a mental health issue. The brain scan images also helped families become more supportive of the person who was struggling, similar to the way they would if a family member had diabetes or cancer. There was an increased sense of compassion and forgiveness.

Lesson #4: If what you’re doing is not working, look at the brain.

Aaron, 52, was a highly successful business owner who was married and enjoying life at all levels. Out of the blue, he woke up one morning in a panic with a terrible sense of impending doom. He was sweating profusely; his heart was racing; and he and his wife had no idea what was wrong. His family physician ran tests and then prescribed Lexapro, an antidepressant medication, for stress. Within a few days the panic attacks worsened, and Aaron was also put on Xanax, a benzodiazepine antianxiety medicine. A week later he woke up with the thought of putting a gun in his mouth and pulling the trigger. Horrified, he came to our clinic after seeing me on television.

Sudden changes in behavior are usually associated with brain trauma, toxins, infections, or a defined emotional trauma. Aaron’s brain SPECT scan showed damage to his PFC and his left temporal lobe, a pattern that looked consistent with a traumatic brain injury. When I asked him about it, he didn’t remember any injuries until I asked him specifically about falls or accidents. At that, he hit his forehead with his hand and told me that two weeks before the first panic attack, he had taken a hard fall off his mountain bike. The front tire hit a jagged rock as he was riding down a steep hill, which sent him flying over the handlebars onto his head. He did not lose consciousness, which is why he didn’t think the injury was important, but he struck the ground so hard his helmet broke.

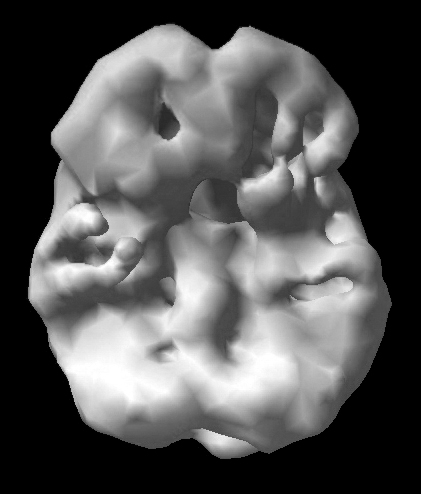

With this information, Aaron’s clinical presentation made sense. To deal with his anxiety, his physician had given him two medications that decrease brain activity —an SSRI (Lexapro) and a benzodiazepine. But because he already had low activity from the injury, the medications were making him worse, even to the point of suicidal thoughts. We needed to activate and rehabilitate his brain, not put a toxic bandage on it. When you damage your brain, you can clearly damage your life. Fortunately, the brain is mendable. On a program that included eliminating the medications that were harmful to him (I am not opposed to medications; these were just the wrong ones for Aaron), adding supplements to nourish his brain, and using hyperbaric oxygen to encourage healing, within eight days he began to feel much better. Six months later he was symptom-free, and his follow-up scan showed significant improvement.

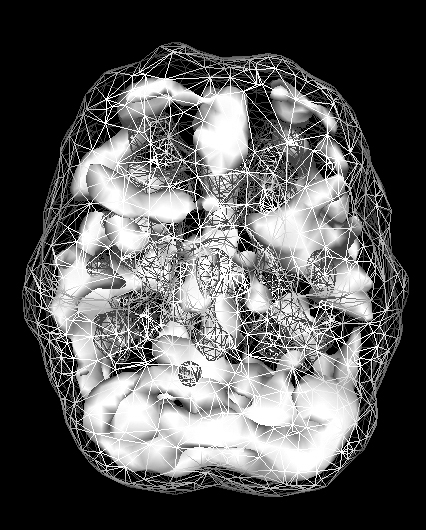

HEALTHY SPECT SCAN

Full, even, symmetrical activity

AARON’S INITIAL SPECT SCAN

Holes indicate severely decreased blood flow in the PFC and left temporal lobe.

AARON’S AFTER TREATMENT SPECT SCAN

Marked overall improvement

Lesson #5: Looking at the brain improves outcomes, and people get better faster.

The most important reason to look at the brain is to improve outcomes. That was my clinical experience when we first started scanning patients, but to find out what the data showed, we started a formal outcome study in 2011 on many of the patients we saw. To date we have six-month outcome results on more than 7,000 patients. The study made it crystal clear that in general, we see people with complex issues who have been unsuccessfully treated by multiple health care providers. On average, our patients have 4.2 diagnoses (such as a combination of ADHD, depression, anxiety, and addictions), they have seen 3.3 medical or mental health providers before coming to us, and they have tried an average of five different medications. After six months, 77 percent of our patients reported they were better. The number went up to 84 percent if they maintained treatment at Amen Clinics. Eighty-five percent reported an improved quality of life. (Our study was published in the peer-reviewed medical journal Advances in Mind-Body Medicine.[355]) In a 2014 Canadian study, non-Amen clinicians and researchers using our method found that psychiatric patients who underwent SPECT-guided treatment improved significantly more than patients who did not.[356]

In another study we published, we found that SPECT changed how the doctor would diagnose or treat patients more than three-quarters of the time. A group of seven psychiatrists evaluated the charts of more than 100 consecutive patients who came to one of our clinics. In stage one, the psychiatrists reviewed the clinical histories and diagnostic checklists, but not the results of SPECT studies, and then gave each patient a diagnosis and treatment plan. (As we’ve discussed, this is how mental health diagnoses and treatment plans are typically done.) In stage two, the evaluators were given access to the SPECT studies for each patient. Having the scans changed the diagnosis or treatment plan in 79 percent of cases. The most clinically significant diagnostic changes were undetected brain trauma (23 percent) and toxicity patterns (23 percent); changes in the treatment arena involved medications or nutraceuticals (60 percent).[357]

Lesson #6: Looking at the brain completely changes the discussion about good and evil.

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but a map is priceless. A map tells you where you are and gives you directions on how to get where you want to go. Without an accurate map you are lost, and that may cost you precious time in getting the help you need —or it may even cost your life. SPECT is a map to help guide people to better brains and better lives.

As our brain imaging work became more widely known across California, we began to receive requests from judges and defense attorneys who were trying to understand difficult behavior and wanted our help. As of today, we have scanned hundreds of convicted felons and more than 100 murderers, including several mass murderers, two of whom I mentioned in Lesson #2. We have learned that people who struggle or do bad things often have troubled brains. That’s to be expected. But what’s more surprising is that many of those brains could be rehabilitated.

As I wrote in Change Your Brain, Change Your Life,

Here is a radical idea. . . . What if we evaluated and treated troubled brains, rather than simply warehousing them in toxic, stressful environments? In my experience we could potentially save tremendous amounts of money by making a significant percentage of these people more functional, so that when they got out of prison they could work, support their families, and pay taxes. Dostoyevsky once said, “A society should be judged not by how it treats its outstanding citizens, but by how it treats its criminals.”[358]

Our brain imaging work has taught us that instead of just meting out punishment for crimes, we must ask why people do bad things and then find ways to help them if they’ll let us. We will be better as a society. The current approach to judgment and punishment in our country seems more about vengeance and retribution than rehabilitation. This is a costly mistake and diminishes the soul of our society. Behavior, at least in part, is related to the actual physical functioning of the brain, which can be improved when put in a healing environment.

If you’re not personally paying attention to your brain, your life can go seriously off track. It’s like the lyrics from the old Phil Ochs folksong “There but for Fortune,” which tell of a prisoner in jail being

a young man with so many reasons why

And there but for fortune, may go you or I

Only I’d argue it should be rewritten: “There but for a healthier brain may go you or I.” And it is not just about criminal behavior. It’s about any troubled behavior, such as suicide attempts, marital affairs, domestic violence, mishandling money, misbehaving at school or work, or acting inappropriately as one ages.

JASON: AFTERMATH OF A BIKE ACCIDENT

Jason was 19 years old and madly in love with Jessica, who loved him back. One day, he got into a bicycle accident where his front tire hit a curb and he flew over the handlebars and landed on the left side of his head. He had a brief loss of consciousness. The emergency room doctor was too busy to say much, except to tell Jason and his parents that he had a mild concussion and should be watched closely for the next few days.

Within a month, Jason’s behavior changed. No one related it to the concussion. Jason became negative, angry, and obsessively jealous, unlike any behavior he displayed before. Jessica became afraid and broke up with him, which made Jason worse. He couldn’t stop thinking of her.

Three months later, Jessica had a new boyfriend. When Jason found out, he went over to her house, tied up the boyfriend, and raped Jessica. The police were called, and there was a standoff, where Jason threatened to kill himself. (He had started having serious suicidal thoughts after the accident.) Jason eventually was taken into custody.

When his defense attorney learned about the bicycle accident, he called a neuropsychologist, who tested Jason, found evidence of potential brain damage, and recommended a brain SPECT scan and my involvement in the case.

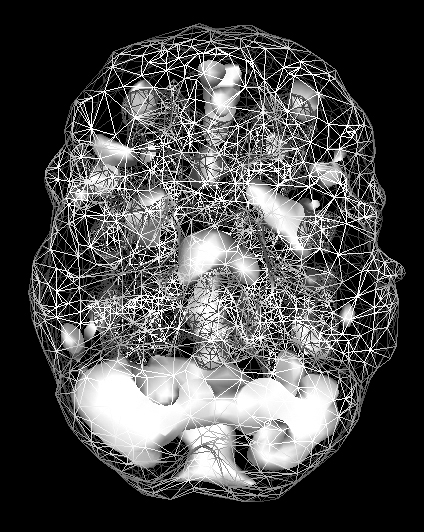

Jason’s scan was very abnormal, indicating trauma to his left temporal lobe (often associated with brain trauma, violence, paranoia, and sometimes suicidal thoughts), excessive activation of his ACG (the gear shifter mechanism in his brain was stuck, and he could not let go of bad thoughts), and low PFC activity (leading to poor impulse control). This pattern is one we often see in cases of violence and obsession.

In jail, Jason was still suicidal. Based on his scans, I recommended a combination of medications to rebalance his brain, an antiseizure medication to help his temporal lobes, and the antidepressant venlafaxine, which helps to calm the ACG and boost the PFC. The medication was helpful; his mood improved and the suicidal thoughts went away. He told me he had not felt that well since before his accident, which was saying something given that he was about to go to trial for several felonies.

The judge in Jason’s trial was running for reelection on a “tough on crime” platform. He was not interested in hearing any of this “new neuroscience nonsense” (his words), and he sentenced Jason to 11 years in prison. When Jason arrived, the overworked prison psychiatrist was also uninterested in hearing about Jason’s brain scans and improvement on medication. He diagnosed Jason with antisocial personality disorder and took him off his medication. Four months later, Jason hanged himself. I am still furious and cry when I think about him. Yes, what he did was horrible. Yes, he should have been punished. People with troubled brains are still accountable for their choices. But to ignore, deny, and withhold treatment for the problems stemming from Jason’s concussion is unconscionable and heartbreaking. We must do better, but it takes the ability to think differently.

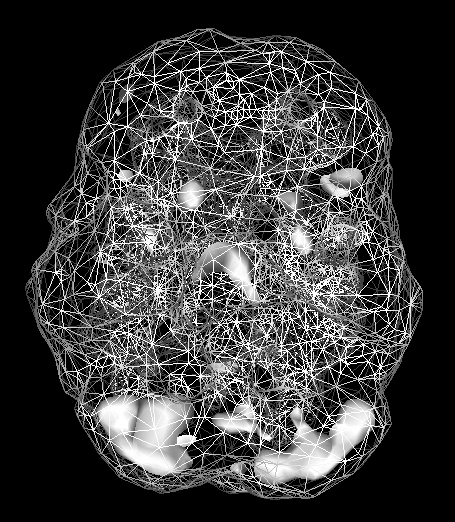

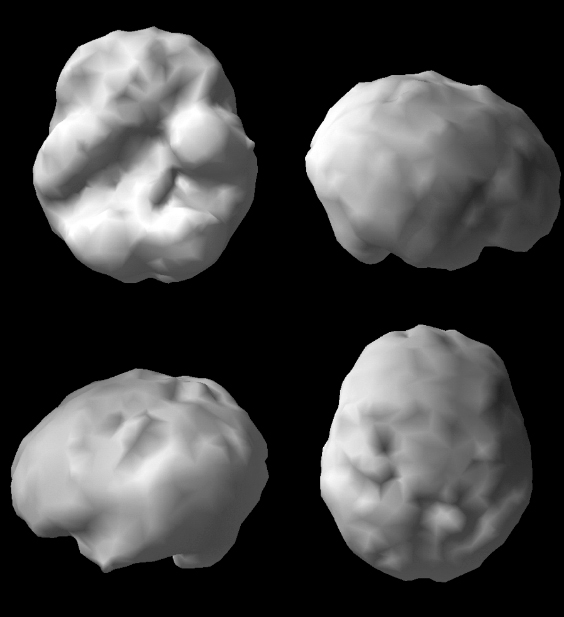

JASON’S SPECT SCAN

Surface scan

Damage to left temporal lobe

Active scan

Increased ACG activity

Of course, neuroscience alone will never completely help us understand the puzzle of troubled behavior; many people who have significant brain dysfunction never commit a crime or seriously hurt others. Behavior is typically driven by a combination of biological, psychological, social, and spiritual forces. However, if you ignore the brain, you’ll never truly understand why people do what they do, and you will never be able to fully help them.

Lesson #7: Looking at the brain helps to prevent mistakes.

Imaging has helped us prevent errors, such as stimulating an overactive brain, calming one that is underactive, or labeling behavior as willful when it was clearly brain-based. Avoiding mistakes saves patients the frustration of unsuccessful treatments, allows us to help them faster, and gives them more hope for the future.

COTI: AN EVIL CYST

When I first met Coti, a 17-year-old, he told me he wanted to cut his mother up into little pieces. His dark, evil thoughts were out of control. He had been through treatment with six psychiatrists and had tried both a 15-month residential treatment program and a 30-day drug treatment program. When we scanned him, I discovered he had the largest cyst I’ve seen, the size of a tennis ball, occupying the space of his left frontal and temporal lobes. His behavior improved when the cyst was removed, although he still had leftover issues because of the damage the cyst had caused.

Over the years I have heard many people complain about the cost of scans, yet for people like Coti, untreated brain problems are dramatically more expensive in terms of money, family stress, and lack of freedom.

COTI’S SPECT SCAN

Damage to the left frontal and temporal lobes from a large cyst

RICHARD: OUTBURSTS OF A TROUBLED BRAIN

Richard ran a large business in Southern California. He was very bright, but over time his business suffered from excessive turnover because he had cruel temper outbursts toward his employees and his wife. He was often apologetic after an incident, but many people refused to work under the stress he caused. His board of directors forced him to see me. Richard’s SPECT scan showed low overall activity in his PFC and both temporal lobes. He also had a cyst in his left temporal lobe. When it was drained and Richard went on a brain rehabilitation program that included supplementation and hyperbaric oxygen therapy, his behavior improved and he was able to keep his job. Two months after the brain surgery, he told me he was doing much better emotionally and had not lost his temper at all, which was a miracle. He was able to step back more easily from stressful situations and be more strategic. He said, “I am amazed that my troubled brain had hijacked so many relationships.”

RICHARD’S SPECT SCAN

Low PFC and temporal lobe activity

Lesson #8: Looking at the brain provides hope.

Over the years, I have signed thousands of the books I have written for appreciative supporters who have bought them. Ever since we started our brain imaging work, I have signed nearly all of them with the words with hope. The images provide hope that there is a better way, and there is hope for healing.

DENNY: A SOLDIER’S STORY

Security is a primary value for my wife, Tana. She grew up in an unsafe, chaotic environment, and even though we live in a very safe neighborhood, she loves training in martial arts (she has two black belts —one in kempo karate and another in tae kwon do) and taking survival courses. She recently took our daughter Chloe on a survival weekend and met Denny, one of her instructors. Her heart broke when she heard his story. He is a former United States Marine who had three traumatic brain injuries, including one in Fallujah, Iraq, in 2007 when he and several of his friends were riding in a truck that was hit by an improvised explosive device (IED). He was knocked unconscious, and when he awoke he was bleeding from multiple places and two of his friends were dead. He was rushed into surgery and was later diagnosed with the chronic effects of multiple traumatic brain injuries and posttraumatic stress disorder. His healing journey involved one medication after another without much relief. He became so hopeless that he tried to end his own life. He finally found a program at Stanford University that was helpful, but it only dealt with the emotional trauma. No one had performed a functional brain imaging study on him, so Tana invited him to the clinic.

Denny’s SPECT scan showed severe damage affecting his PFC in the front of his brain (focus, forethought, judgment, and impulse control), left temporal lobe (memory, learning, and dark thoughts), and occipital lobes in the back (visual processing). The good news was that it was clear that his brain could be dramatically improved with the right treatments.

DENNY’S SPECT SCAN

Holes indicate areas of severely decreased blood flow.

After looking at his scan, Denny was actually grateful his brain didn’t look worse and that he had a “physical” reason for feeling as awful as he did. He was now motivated to make his brain much better.

A week later he wrote to Tana, “It’s only been a week, and I can already feel a difference. Since the scan I have increased my activity level (fitness), modified my diet, and maintained the supplement regimen. I’m doing great! My energy level and attention span have increased, allowing me to focus more. My daughter and I have been outdoors every day. Since I started adjusting my habits, I am happier and more positive. I really want for my brain to have an improvement that can be visible in my scan. That motivation is what has gotten me back to normal.”

Lesson #9: Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia start years, even decades, before people have any symptoms.

One of the most profound lessons from our brain imaging work is that Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia can be seen on SPECT scans years before people have any symptoms. SPECT is a leading indicator of problems, meaning it shows evidence of the disease process years before people show signs of it. Anatomical studies, such as CT and MRI, are lagging indicators. They show problems later in the course of the illness, when interventions tend to be less effective.

This lesson led us to advocate for doing scans and implementing prevention techniques as early in a person’s life as possible. If you consider the fact that 50 percent of the population will get Alzheimer’s disease by the age of 85, prevention should really take center stage in anyone who wants to live to 85 or beyond.

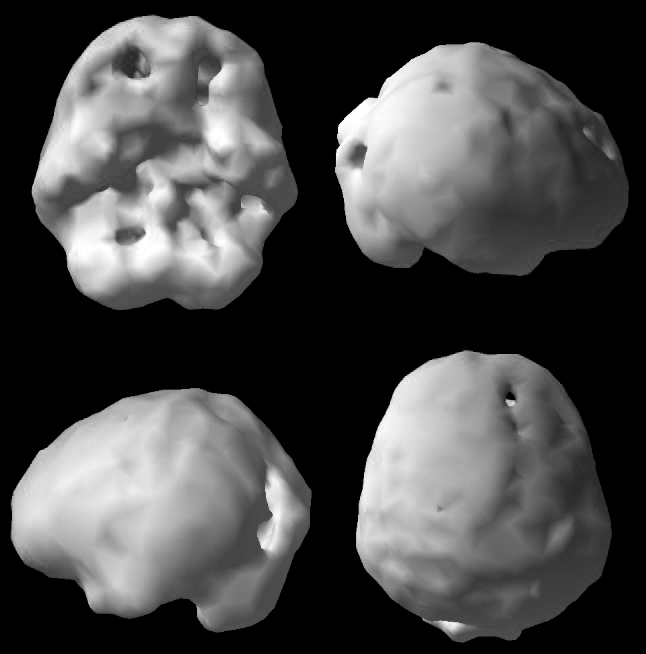

Chalene Johnson is a bestselling author, motivational speaker, and mother of two. Despite all her success, when she first came to see us she struggled with memory, focus, distractibility, procrastination, and always being late to appointments. To give you an idea of how bad it was, she had to shut herself in the basement closet just to get work done because any noise seemed to distract and irritate her. To make things worse, Chalene had a family history of Alzheimer’s disease.

Her SPECT scan looked terrible. It showed evidence of ADHD with low activity in her frontal lobes, as well as low activity in areas vulnerable to Alzheimer’s. The scan really got her attention. Over the next two years, she did everything we asked. Her follow-up scan showed dramatic improvement, decreasing her risk of future problems. More important, she told me that her performance at work, at home, and in her relationships all improved. Plus, she was finally able to get out of the basement!

CHALENE’S “BEFORE” SPECT SCAN

Low PFC activity (consistent with ADHD)

Low activity indicating vulnerability to later Alzheimer’s

AFTER TREATMENT SPECT SCAN

Marked overall improvement

Lesson #10: The most important lesson from 150,000 scans is that you can change your brain, and it will change your life.

This is the biggest and most exciting lesson our patients have learned from our work. And it is personal.

ANDREW: MY NEPHEW’S BRUSH WITH DISASTER

I got a call late one night in April 1995 that my nine-year-old godson Andrew, who’s also my nephew, had attacked a little girl on the baseball field that day for no particular reason. I was on the phone with Sherrie, my sister-in-law, feeling shocked, and I said, “Excuse me?”

She said, “Danny, he’s different. He’s mean. He never smiles anymore. I went into his room today, and I found two pictures that he had drawn. In one of them, he was hanging from a tree. In the other picture, he was shooting other children.” In retrospect, Andrew was Columbine, Sandy Hook, Aurora, and Parkland waiting to happen.

I told Sherrie I wanted to see Andrew the next day. They drove from Southern California to Northern California, where we had our first clinic. When I walked into my office and saw Andrew sitting on the couch, my heart melted. I loved this child and was terribly worried about him. I said, “Honey, what’s going on?”

He said, “Uncle Danny, I’m mad all the time, and I don’t know why.”

I asked, “Is anybody hurting you?”

He said, “No.”

“Is anybody teasing you?”

And he said, “No.”

“Is anybody touching you in places they shouldn’t touch you?” I was searching for answers to his senseless behavior.

And he said, “No.”

My first thought was You have to scan him. My next thought, because you know we’re always talking to ourselves, was You want to scan everybody. You know, maybe it’s because he’s the second son in a Lebanese family. You’re the second son in a Lebanese family. Then all of a sudden, the rational voice in my head said, Stop it! Nine-year-old children do not attack people for no reason. Scan him. If his scan is normal, then you can explore other reasons for his behavior.

I went with Andrew to the imaging center and held his hand while he held his teddy bear and got scanned. When his brain scan came up on the computer screen, I could see that Andrew was missing the function of his left temporal lobe. I looked at Dr. Jack Paldi, my mentor, and said, “Why doesn’t he have a left temporal lobe?”

To make sure Sherrie and my brother Jim wouldn’t hear, Dr. Paldi wrote on a piece of paper, “It’s a cyst, a stroke, or a tumor.” I was sad, because something was clearly wrong, yet also relieved that something was wrong —there was a possible explanation for Andrew’s unusual behavior. Andrew had an MRI that day, which showed he had a cyst (a fluid-filled sac) the size of a golf ball occupying the space where his left temporal lobe should have been. By that time in 1995, we had already correlated left temporal lobe issues with violence. I called Andrew’s pediatrician in Southern California and asked him to find someone to drain the cyst.

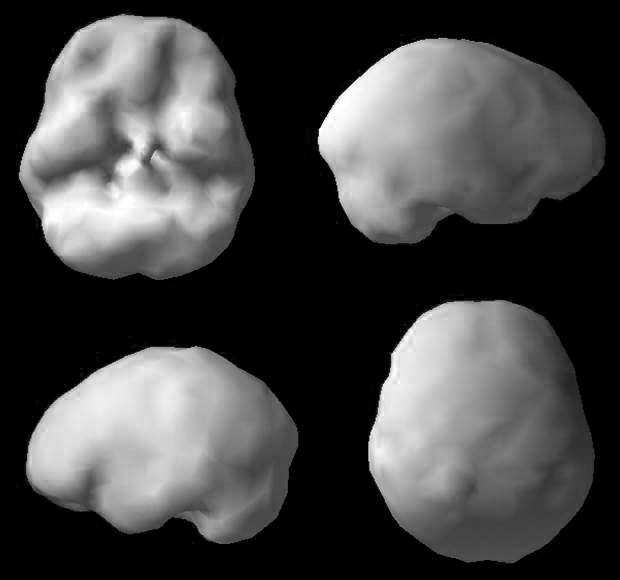

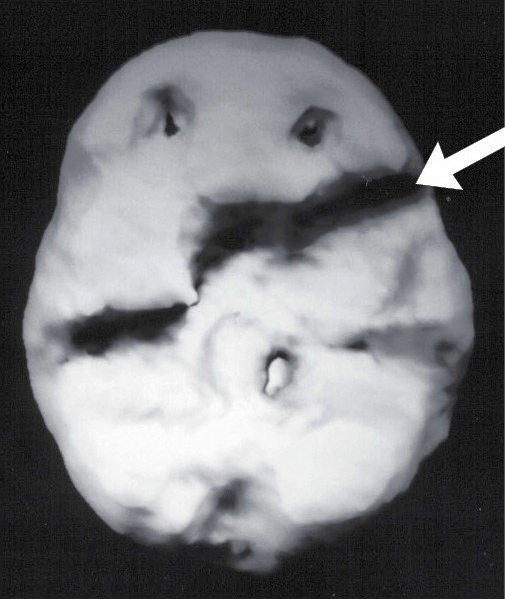

ANDREW AND HIS MISSING LEFT TEMPORAL LOBE ON SPECT

ANDREW (AGE 9)

Andrew and his dog, Buster

ANDREW’S SPECT SCAN

Missing function of the left temporal lobe

Two weeks later, the pediatrician called me back and said he had talked to three neurologists. None of them recommended we do anything about the cyst, and they thought it probably had nothing to do with Andrew’s behavior problems. He told me, “They wouldn’t operate on him unless he had real symptoms.”

Furious, I said, “Let me get this right. I have a homicidal, suicidal boy. What do you mean by real symptoms?”

“I think they mean seizures, or he loses consciousness, or he has speech problems,” he replied defensively.

“This is insanity,” I replied and hung up.

I then called a friend of mine at Harvard, who is a pediatric neurologist, and she told me the same thing. Frustrated, I thought to myself, Neurologists . . . neurologists . . . neurosurgeons. Neurosurgeons operate. I called the pediatric neurosurgery department at UCLA and talked to Dr. Jorge Lazareff, who later became famous for separating the Guatemalan twins who were connected at their heads. He was famous to me before then because when I told him about Andrew, he said, “When cysts are symptomatic, we drain them. Obviously, he has serious symptoms.”

No kidding, I thought to myself.

After surgery, I received two phone calls. One was from Sherrie, who was so excited. She told me the surgery went really well, and when Andrew woke up afterward, he smiled at her. She said, “Danny, he hasn’t smiled for a year.”

The second call was from Dr. Lazareff, who said, “Dr. Amen, that cyst was so aggressive and put so much pressure on Andrew’s brain that it actually thinned the bone over his left temporal lobe. His temporal bone was eggshell thin. If he had been hit in the head with a ball, it would have killed him instantly. Either way, Andrew would have been dead in six months if you hadn’t persisted.”

ANDREW AFTER SURGERY

It’s a day I’ll never forget —the day I lost my anxiety about our brain imaging work and the criticism I had endured. Nine hundred ninety-nine psychiatrists out of a thousand would have medicated Andrew or put him in psychotherapy. I became even more passionate than ever about our work. Andrew was blessed in the sense that he had someone who loved him paying attention to his brain when his behavior was off. Now, 23 years later, Andrew is married, employed, owns his own home, and pays taxes. Because someone looked at his brain, he has been a wonderful son and husband and will be a better father and grandfather.

How do you know unless you look? If you don’t look, you hurt people, and that’s not fair. That’s not science. That’s not medicine. It’s stupidity. We can do better. When I think of the single most important lesson I’ve learned from the 150,000 scans we’ve done, it is this: You can literally change people’s brains, and when you do, you change their lives.

In November 2017, unbeknownst to me, someone posted on Facebook a six-minute clip of me telling Andrew’s story during a lecture I gave at Saddleback Church in Southern California.[359] The post went viral, and within a few weeks it had 38 million views, more than 700,000 shares, and more than 25,000 comments. Many of the comments made me cry. Here are a few that touched my soul.

From JG:

I hadn’t seen my brother in 10 years since we were afraid of his behavior.

When he was young, he was invited to every major college because he was brilliant, yet over the years, especially after he was in the military, he began to decline mentally. He had several head injuries in his life, one major one while in the service. My brother had been aggressive with erratic behavior for years, and was diagnosed with schizophrenia, as was our mother. It seemed logical at the time 20 years ago.

My brother became homeless, an alcoholic, and addicted to painkillers from being hit by a drunk driver and ended up in a VA group home. He was robbed and attacked during that time. His injuries caused him to need two brain surgeries last year.

Out of the blue my other brother and I got a call from a young psychiatrist from the VA hospital telling us that our older brother had a severe infection, pressure, and scarring in his left temporal lobe. His brain scan showed several injuries and infection; and he wanted the hospital to clean out the scar tissue, but the head surgeon didn’t want to perform the surgery, believing our brother was a “homeless drunk.” The hospital was keeping our brother in the psychiatric ward for aggressive behavior, where we went to visit him —one of the saddest days of my life to see him there. The young psychiatrist had seen my brother’s brain scan and thought much of his behavior was due to his injuries and pressure on his brain. He convinced another neurosurgeon to do my brother’s brain surgery. . . .

One year later, my brother has returned to us, like a new person, it’s an absolute miracle. It’s very sad to think he lived being considered schizophrenic for all those years. I asked the young psychiatrist why he pushed so hard to help my brother, and he said he could tell by talking to him that he seemed far too brilliant and knew he must have a family somewhere so he went looking for us. He told me he had another case very similar to our brother’s injuries and that the other patient had become aggressive after a car accident, so he decided to search for family and push for my brother to have surgery. God bless such a brilliant man for practicing medicine.

From SC:

Starting at age seven, I was severely depressed. That’s not normal. Finally, at age 35, I found a psychiatrist who demanded a brain MRI. What did they find? Mesio temporal sclerosis (scarring of the temporal lobe), a form of epilepsy that caused horrible symptoms. I’m on medication and have a whole new life.

From JP:

I spent years suffering from anxiety, depression, a changed personality. I would have “episodes” where words, written or spoken, made no sense to me. I told my psychologist and my doctor about these episodes. They just said they didn’t know what it was. Finally, I changed psychiatrists and she sent me for an EEG. Something wasn’t right so I was sent for an MRI where they found a tumor (meningioma). They immediately sent me to the hospital and three days later removed it. Five years later I have no anxiety, no depression, no weird episodes. I am off all medications. And I am myself again. Thank God my psychiatrist got things moving for me.

20 LESSONS FROM OUR PATIENTS

As I was writing this chapter, I asked our patients to tell me the biggest lessons they learned from looking at their brains. Here are 20 answers, chosen from among many.

- Prior to having my scan, I was misdiagnosed and thus mistreated. After having my scans, it is like I have a new life.

- I would say that having my son scanned was what changed my life the most and made me a better mom. Seeing his brain made me realize he wasn’t just being defiant, but that when he concentrated, his brain was extremely anxious. It made me realize that instead of yelling and fighting with him like I usually would, I needed to be more patient. He is now doing well in school and playing basketball like a rock star, and our relationship has never been better.

- I learned as an adult that I still have lasting brain effects from heart surgery as an infant. It helped explain many of my struggles and gave me direction on how to get help.

- If I didn’t see the damage to my brain, I wouldn’t have taken the actions needed to make it better.

- The first scan helped me realize I wasn’t crazy. It made total sense I had focus and anxiety issues, but I never admitted it to myself. The second scan three months later verified the supplements and diet changes had calmed my brain dramatically, which is why I was feeling so much better.

- I never got a scan, but I use the images every day to help children understand the devastating effects of alcohol on the brain. I lost my sister to a DWI crash and she was the one drinking. Shortly thereafter, [when] I became a drug and alcohol prevention educator, I found Dr. Amen’s book Change Your Brain, Change Your Life. I learned so much and now show his video, Which Brain Do You Want? —which shows brain scans of healthy teenagers versus drug-abusing teenagers —to both high school and middle school children. It totally changes the way the kids view drugs and their brains.

- One of the things that I learned was how important it was to me to have a healthy brain. At the time, I didn’t think about my brain health daily, because out of sight, out of mind (ironically).

- I had no idea how I was hurting my brain, and my future, with alcohol and weed.

- The SPECT scan made it real to me that the head trauma I had from a car accident and playing football had me headed for dementia. After seeing the scan, I know what to do to help my frontal cortex get bigger, rather than continue [to] shrink. Yes, size does matter!

- My scan showed areas of overactivity that were contributing to my anxiety. I was put on the right medicine for my brain, and WOW, almost overnight I noticed the difference. Little things didn’t bother me anymore.

- I don’t have to helplessly stand by and wait for my brain to deteriorate. It showed me that there are many options to keep my brain healthy.

- My SPECT scan helped me (and my family!) better understand who I am and then taught me how to be the best version of myself! I went from feeling crazy and frustrated to feeling empowered and energized. Information + action = life change!

- The SPECT scan allowed my doctors to tailor treatment to my specific brain. Finally, 10 years since my last concussion, I can work full-time again in my academic job.

- I was once in denial that I had depression and anxiety, due to the lack of physical proof. With the SPECT scan, I was able to see with my own eyes the workings of my brain, which allowed me to accept the truth and move forward with the necessary treatment.

- The most important lesson from my SPECT scan was that although my cognitive and visual issues are “all in my head,” they are not a “figment of my imagination”! It’s life-changing, real data that must be respected! And there is help available!

- I oversaw care of my mother for 19 years, through her ever-worsening dementia. It was a horrible, draining experience. After my mother died, I felt concerned about my own brain, so, at 63, I had a SPECT scan. My scan came back clear, which gave me peace of mind for my future. I also used the opportunity to become my best version of brain health. Since my mother lived to 93, I figure I saved myself 30 years of worry and more. I am very, very grateful!

- I had my brain scanned and the results were shocking. I have ADD. I’m 61 years old and have been searching for the missing piece of my brain since I quit high school at age 16 because I couldn’t sit still or focus on schoolwork. Today it’s possible to change my brain/change my body. I’ve lost weight, I feel better and have better relationships, work is better, and I’m happy.

- I learned that the symptoms I was experiencing were due to overactivity in certain areas of my brain. Therefore, I learned self-compassion. It was a huge gift.

- Getting the scan and learning where I was overactive and underactive was priceless. I could now have a more accurate game plan to address my specific needs, versus just a shotgun approach. Having more information allowed for a more accurate diagnosis and treatment plan, which in the end led to a quicker and more permanent solution to the issues I was having. It’s the closest thing to having a crystal ball that I have seen.

- Your brain WANTS to heal itself, and given the right conditions, it CAN.

WHEN SHOULD YOU THINK ABOUT GETTING A FUNCTIONAL IMAGING STUDY, SUCH AS SPECT?

We order SPECT studies on most of our patients because they generally come to us after they have failed to get better with other specialists and therapies. Many patients tell us, “You are my last hope.” In these cases, we need more detailed information to see if we can identify something that has been overlooked. In general, I think of SPECT as radar. If it is sunny outdoors, it is easy for pilots to land planes at the airport. So if you have a simple case, you don’t need a scan. But if it is stormy out, with dark clouds, lightning, and thunder, radar can be lifesaving. Likewise, if your case is complicated and you have not gotten better with other providers or treatments, a scan could be lifesaving.

Here are answers to several common questions about SPECT.

Will the SPECT study give me an accurate diagnosis?

No. A SPECT study by itself will not provide a diagnosis. SPECT studies help the clinician understand more about the specific function of your brain. Each person’s brain is unique, which may lead to unique responses to medicine or therapy. Diagnoses about specific conditions are made through a combination of clinical history, personal interviews, information from families, diagnostic checklists, SPECT studies, and other neuropsychological tests. No imaging study alone is a “doctor in a box” that can give accurate diagnoses on individual patients.

Why are SPECT studies ordered?

Some of the common reasons include

- Evaluating seizure activity

- Evaluating cerebral vascular disease

- Evaluating cognitive impairment and dementia

- Evaluating the effects of mild, moderate, and severe head trauma

- Suspicion of an underlying organic brain condition, such as seizure activity contributing to behavioral disturbance, prenatal trauma, or exposure to toxins

- Evaluating aggressive behavior that’s atypical or unresponsive to treatment

- Determining the extent of brain impairment caused by drug or alcohol abuse

- Subtyping ADHD, anxiety, depression, addictions, and obesity

- Evaluating treatment-resistant couples for underlying conditions that might be contributing to their relationship issues

- General wellness screenings for people who are interested in brain optimization

Are there any side effects or risks from the study?

The study does not involve a dye, and people do not have allergic reactions to the study. The possibility exists, although in a very small percentage of patients, of a mild rash, facial redness and edema (swelling), fever, and a transient increase in blood pressure. The amount of radiation exposure from one brain SPECT study is approximately the same as from one head CT scan, or one-third of an abdominal CT scan. Pregnant women should not have a SPECT study.

How is the SPECT procedure done?

The patient is placed in a quiet room, and an intravenous (IV) line is started. The patient remains quiet for approximately 10 minutes with eyes open to allow his or her mental state to equilibrate to the environment. The imaging agent is then injected through the IV. After another short period of time, the patient lies on a table and the SPECT camera rotates around his or her head (the patient does not go into a tube). The time on the table is approximately 15 minutes. If a concentration study is ordered, the patient returns on another day to repeat the process; a concentration test is performed during the injection of the isotope.

Are there alternatives to having a SPECT study?

In our opinion, SPECT is the most clinically useful study of brain function. There are other studies, such as quantitative electroencephalograms (QEEGs), positron emission tomography (PET) studies, and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRIs). PET studies and fMRIs tend to be more costly, and they are performed mostly in research settings. QEEGs can provide useful information, but they often do not give information on the deep areas of the brain.

Does insurance cover the cost of SPECT studies?

Reimbursement by insurance companies varies according to your plan. It is a good idea to check with the insurance company ahead of time to see if a SPECT study is a covered benefit.

Is the use of brain SPECT imaging accepted in the medical community?

Brain SPECT studies are widely recognized as an effective tool for evaluating brain function in seizures, strokes, dementia, and head trauma. There are literally thousands of research articles on these topics. In our clinic, based on our experience over 28 years, we have developed this technology further to evaluate aggression and nonresponsive psychiatric conditions. Unfortunately, many physicians do not fully understand the application of SPECT imaging and may tell you that the technology is experimental, but more than 6,000 medical and mental health professionals around the world have referred patients to us for scans.

We’ve learned so much from SPECT scans, and I’m proud of the difference we’ve made in the lives of thousands of patients. Whether or not you pursue a scan, the most important thing I want you to take away from this chapter is hope. You can change your brain, and that can change your life.

10 PRACTICAL LESSONS FROM 150,000 SCANS —HOW THEY HELP YOU FEEL BETTER FAST AND MAKE IT LAST

- Current psychiatric diagnostic models are outdated because they don’t assess the brain.

- Psychiatric diagnoses are not single or simple disorders; they all have multiple types, and each requires its own treatment.

- Looking at the brain decreases stigma, increases compliance with treatment, and completely changes the discussion around mental health.

- If what you’re doing is not working, look at the brain.

- Looking at the brain improves outcomes, and people get better faster.

- Looking at the brain completely changes the discussion about good and evil.

- Looking at the brain helps to prevent mistakes.

- Looking at the brain provides hope.

- Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia start years, even decades, before people have any symptoms.

- The most important lesson from 150,000 scans is that you can change your brain, and it will change your life.

TINY HABITS THAT CAN HELP YOU FEEL BETTER FAST —AND LEAD TO BIG CHANGES

Each of these habits takes just a few minutes. They are anchored to something you do (or think or feel) so that they are more likely to become automatic. Once you do the behaviors you want, find a way to make yourself feel good about them —draw a happy face, pump your fist, or do whatever feels natural. Emotion helps the brain to remember.

- When I read about someone who has done something terrible, I will wonder what might have been going on in his or her brain.

- When someone is being difficult with me, I will try not to overreact, knowing the other person may have issues I am unaware of.

- If I have struggled with mental health issues and get down on myself, I will say to myself, “My brain can be better if I do the right things for it.”