CHAPTER 6

HEALING CONNECTIONS

HOW TO IMPROVE ANY RELATIONSHIP

The magic ratio is 5:1. We have found that as long as there are five positive interactions for every negative interaction, a couple can have a stable and happy relationship over time.

JOHN GOTTMAN, PHD

Truth is, everybody is going to hurt you: you just gotta find the ones worth suffering for.

ATTRIBUTED TO BOB MARLEY

Good relationships keep us happier and healthier, according to a 75-year longevity study from Harvard University. Positive social connections help us live longer, while loneliness kills us early. Sadly, one in five Americans is lonely, which means this is a public health problem too. Another lesson from the study: Being in positive, warm, satisfying relationships keeps our brains and bodies healthy into older age, while being in relationships filled with conflict is associated with sickness and early death.[156]

Emotional crises, panic attacks, depression, and obsessive behaviors are often triggered by the loss or threatened loss of a relationship. Marital problems, affairs, domestic violence, breakups —all of these relationship problems prompt people to come and see us at Amen Clinics. It is common for us to hear statements like “My marriage is falling apart,” “All my relationships are failing,” or “I want to be a better husband and stop hurting my family.” Improving your social connections is one of the best ways to start to feel better fast and make it last.

Unlike polar bears, humans require social interaction to stay healthy. We have a fundamental need to belong that’s just as essential as our need for food and water. People who are socially connected are happier and healthier, and they live longer.[157] People who are married are less likely to develop dementia than those who have never been married (lifelong singles have a 42 percent higher risk) or those who are widowed (their risk is 20 percent higher), according to recent research. (The association did not apply to divorced individuals.[158]) Loneliness or disconnection from others is also associated with an increased rate of depression, cognitive decline, and dementia.[159] Being in loving relationships is every bit as important as sleep, a healthy diet, and exercise.

Naomi Eisenberger, PhD, a professor in social psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles, has demonstrated in a fascinating series of studies that loss, or being socially excluded or rejected, activates the physical pain centers in the brain, and those who are more sensitive to physical pain are also more sensitive to social rejection. In addition, Eisenberger has shown that taking pain medication, such as acetaminophen (Tylenol), can help to ameliorate the pain of social rejection.[160] When it comes to the brain, a broken heart is not so different from a broken leg.

Rejection can also trigger aggression. Animals that are in physical pain often react toward others with aggression. Researchers who analyzed 15 school shooters in 2003 found that all but 2 suffered from social rejection.[161] Suicide, murder, and murder-suicides are often the consequence of broken social bonds.

Relating to others in healthy, effective ways is ultimately a brain-based skill, yet even most marital therapists get zero training on or about the brain. When your brain is healthy, you can perceive others more accurately, have good control over your emotions, and act in healthy ways that bring people closer to you. Your brain allows you to read social cues, listen, respond appropriately, deal with conflict, set effective boundaries, act inclusively, and be attentive in moments of interaction. A brain with short circuits, whether yours or someone else’s, often interrupts effective relationships. Stop and think about it: Brains nurture, influence, stimulate, irritate, calm, and incite each other. Being raised by a parent with a difficult brain, having a spouse or boss with brain problems, or even dealing with a friend, teacher, or coworker who needs brain help can all cause immeasurable stress. Understanding the neuroscience of relationships will give you an uncommon advantage. As you care for your brain, all of your relationships are likely to improve.

EIGHT BRAIN-BASED HABITS TO ELEVATE YOUR RELATIONSHIPS

Professor Howard Markman, director of the Center for Marital and Family Studies at the University of Denver, can predict with 90 percent accuracy if a couple will get divorced or stay married. He can make the prediction after watching a 15-minute conversation between the spouses where they are instructed to discuss an issue upon which they disagree. If the couple’s argument involves the habits of blaming, belittling, escalation, invalidation, or withdrawal, their future is not likely to be happy. However, if the couple communicates respect and shared purpose and stops escalation in a civil way, the future looks much more positive. Markman also found that he could reduce divorce by one-third among couples to whom he taught several critical skills.[162] Good relationship habits can be learned and enhanced by a healthy brain that can remember and implement them.

This chapter will provide you with eight brain-based habits clinically proven to increase your relationship skills. In part, these techniques come from research in the field of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT). Enhancing interpersonal skill has proven effective in reducing anxiety, depression, and stress, and in improving both business success and marital satisfaction. There are more than 125 studies showing IPT’s effectiveness.[163] Even brain imaging studies have shown how improving relationships can help normalize the brain in people who are depressed.[164] The acronym RELATING will help you remember the essential relationship habits.

- R is for Responsibility

- E is for Empathy

- L is for Listening and good communication skills

- A is for appropriate Assertiveness

- T is for actual, physical Time

- I is for Inquiry and correcting negative thoughts

- N is for Noticing what you like more than what you don’t

- G is for Grace and forgiveness

R IS FOR RESPONSIBILITY

Responsibility is not about blame. It is about your ability to respond to whatever situation you are in, as in these examples:

“It is my job to make this relationship better.”

“I have the power to improve how we communicate and act toward each other.”

“I have influence in my relationships that I exert in a positive way.”

“I am responsible for my behaviors in our interactions.”

People who take responsibility for their own behavior do better in relationships. Those who constantly blame others set themselves up for a lifetime of problems. Yet blame is fast and easy and even seems hardwired in the brain. In a Duke University study, researchers scanned the brains of volunteers while they were asked to judge the intent of others in multiple situations. One of the scenarios was “The CEO knew the plan would harm the environment, but he did not care at all about the effect the plan would have on it. He started the plan solely to increase profits. Did the CEO intentionally harm the environment?” Eighty-two percent of the volunteers said the CEO’s action was deliberate. When researchers replaced the word harm with help, only 23 percent said it was intentional. The scientists discovered that when volunteers “blamed” the CEO, their brains reacted faster and more powerfully, activating the amygdala, which is involved with the feelings of fear and threat. Those who saw positive intention in the CEO’s behavior reacted more slowly, with less activity in the amygdala and more activity in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), the brain region discussed in chapter 3 that’s associated with forethought and executive function.[165]

Blame is quick, common, and possibly self-protective against aggression, but it is also the first and most devastating hallmark of self-defeating behavior in relationships. When you blame someone else and fail to take responsibility for your own behavior, you become a victim of other people and are powerless to change anything. If you struggle with blame, you’ll typically hear yourself say things like

“It wasn’t my fault that you took things the wrong way.”

“That wouldn’t have happened if you had listened to me.”

“It’s your fault that we are having trouble.”

The bottom-line statement goes something like this: “If only you had done something differently, then I wouldn’t be in the predicament I am in. It’s your fault, and I am not responsible.”

Deflecting responsibility for relationship troubles or making excuses when things don’t go as you would like is the first step in a dangerous downhill slide. The slide typically follows this sequence:

Deflect responsibility

“It’s your fault.”

See life as beyond personal control

“My life would be better if you hadn’t done . . .”

Feel like a victim

“If only you would be different, then . . .”

Give up trying

“It is never going to work. Why even try?”

Deflecting responsibility temporarily makes you feel better, but it also reinforces the idea that your life is out of your control, that others can determine how things will go for you. This causes inner turmoil, leading to anxiety and feelings of helplessness.

Sarah came to see me for marital stress. She had been in psychotherapy with another psychiatrist for more than three years but seemed to be getting nowhere. She complained that her husband was an alcoholic who mistreated her. She was often tearful and depressed and had problems concentrating. In our initial interview it was clear that she took no responsibility for how her life was turning out. She blamed her first husband for getting her pregnant at age 19 and felt “forced” to marry him, but she complained that he was unmotivated, so she divorced him. Then, in succession, she impulsively married two different men who were alcoholics and physically abusive. Tearfully, she expressed feelings of being continually victimized by men, including her current husband.

At the end of the session I asked her what she had done to contribute to her problems. Her mouth dropped open. Her previous psychiatrist had been a good paid listener, but he never challenged her notion of helplessness. At the beginning of the next session she told me that she almost didn’t come back to see me. She said, “You think it’s all my fault, don’t you?” I replied, “I don’t think it’s all your fault, but I think you have contributed to your troubles more than you give yourself credit for; and if it’s true that you’ve contributed to your problems, then you can do things to change them. As long as you stay an innocent victim of others, there is nothing you can do to help yourself.”

Over several sessions Sarah got the message of personal responsibility and made a dramatic turnaround. She had grown up in a severely abusive alcoholic home, where she really was a victim of her circumstances, causing her amygdala to become overactive and making her feel constantly threatened. Unfortunately, she maintained that role in her adult relationships, including at work. Her unconscious continuation of her abusive childhood was ruining her ability to have control in her life.

Invariably, in classes where I teach this concept, some people will tell me that their problem is not deflecting responsibility but rather taking too much on themselves. These two concepts, deflecting responsibility and putting too much on oneself, are not mutually exclusive. A good “personal responsibility” statement goes something like this: “Bad things have happened in my life, some of which I had something to do with and some of which I did not. Either way, I need to learn how to respond effectively to whatever situation I am in.” Responsibility means you have the ability to respond in a positive, helpful way.

Taking responsibility in relationships means continually asking yourself what you can do to make the relationship better. When my patients thoughtfully evaluate and change their own behavior, their relationships often dramatically improve. In my experience, the idea that we have no control or influence over the behavior of others is just not true. I often ask patients what they do to make their relationships better, and they usually can come up with a number of positive behaviors. Then I ask them what they do to make the relationships worse. Initially, they hesitate, not wanting to admit to their own negative actions, but after a bit of time they start to own up to the myriad behaviors they might need to work on. Here is an example.

Eight-year-old Carlos was sitting in my office because he had behavioral problems, especially at home. He started by telling me how much he hated his younger sister. “She irritates me all the time,” he said. “I have no choice but to yell at her and hit her.”

When he said he had no choice, my eyebrows raised.

Seeing my reaction, he justified his behavior further. “I have no choice; she irritates me all the time.”

“What do you do to irritate her?” I asked softly.

“Nothing,” he said. He paused and repeated, “Absolutely nothing.”

I sat quietly.

“Well —” He paused, and then showed a wry smile. “Well, I take some of her things sometimes.”

“Anything else?”

Carlos looked like he was thinking hard and then said, “I yell at her, tell her she cannot play with me, and ignore her when she talks to me.”

“Okay,” I said. “You do irritate her. I sort of suspected it. But what do you do that makes her happy?”

He then listed several things he did that helped them get along better, including playing with her, helping her with her kindergarten homework, saying thank you, and smiling at her. He had a lot more power than he believed. Helping Carlos tap into his power to make his relationship with his sister better, as well as know his ability to make things worse, helped change his victim mentality and ultimately his behavior.

What can you do today to make your relationships better? You win more in relationships when you ask yourself this question and stay away from blaming others.

E IS FOR EMPATHY

If, as a result of reading this book, you get only one thing —an increased tendency to think always in terms of the other person’s point of view, and see things from that person’s angle as well as your own —if you get only that one thing from this book, it may easily prove to be one of the stepping-stones of your career.

DALE CARNEGIE, HOW TO WIN FRIENDS AND INFLUENCE PEOPLE

Once when my family and I were on vacation in Hawaii, I was reading a book to our daughter Chloe, then four years old, when her mother walked into the room and accidentally bumped into the corner of the television armoire. Watching this happen, Chloe immediately said, “Ouch,” as if she felt the pain herself. Touched by her caring, Tana gave Chloe a hug and told her she was okay. That simple interaction stayed with me for the whole trip. It was the essence of empathy, the human ability to feel what others feel. Chloe’s mirror neurons were at work.

In the late 1990s, Italian neuroscientists Giacomo Rizzolatti, Leonardo Fogassi, and Vittorio Gallese were recording activity of the lower frontal lobes of the macaque monkey when they experienced a moment of research serendipity. As the scientists mapped the electrical activity of the monkey’s actions, Dr. Fogassi selected a banana from a nearby fruit bowl. As he reached for the banana, the monkey’s brain reacted as if he, too, were reaching for the fruit, even though he had not moved. He was playing out in his head what the researcher was doing. The researchers labeled the responsible cells “mirror neurons” and later discovered them in humans.[166] These neurons “allow us to grasp the minds of others,” the researchers noted,[167] which is why we open our own mouths when we feed a baby or yawn when others start to yawn first. We “play” their minds in our brains.

THE MIRROR NEURON SYSTEM

Researchers have found that children with autism, who often display social skill deficits, have problems in their mirror neuron systems. This system is important to empathy. When it is healthy, we can experience the feelings of others. When the system works too hard, we can become too sensitive, which would make us terrible doctors or nurses, as we could be crying all the time in response to others’ pain. When it does not work hard enough, we could hurt others and it wouldn’t bother us. As is true with so many parts of the brain, a healthy system helps us most.

Empathy helps us navigate the social environment and answer questions such as these: Is this person going to feed me? Love me? Attack me? Faint? Run away? Cry? The more accurately we can predict the actions and needs of others, the better off we are. The ability to “tune in” and empathize with others is a prerequisite for understanding, attachment, bonding, and love —all of which are important for our survival.

In several studies about why executives fail, “insensitivity to others” or a lack of empathy was cited more than any other flaw as a reason for derailment. Phrases like the following were used about those who did not succeed:

- He never negotiated; there was no room for any views contrary to his.

- She could follow a bull through a china shop and still break the china.

- He made others feel stupid.

- She was always talking down to her employees.

- Whenever something went right, he took all the credit. Whenever things fell through, heads would roll.

- It was her way or no way. If you disagreed with her, you were out.

Lack of empathy can cause failure in almost any endeavor. A lack of interpersonal skill not only causes others to avoid you; it can make them angry and feel active ill will toward you. Coworkers may look the other way if you are making serious mistakes; spouses may start finding fault in any area they can to retaliate for their hurt; and acquaintances may begin making excuses to decrease the time they spend with you. Lacking empathy also has a serious isolating effect that not only causes loneliness but also decreases honest feedback from others and cuts you off from coworkers’ or friends’ creativity and knowledge. One example from my practice was of a supervisor who returned to his office after being chewed out by the owner of a company. Upset, he snapped at his assistant for not having a report ready. She had just returned from taking her child to the emergency room because he had cut his head open falling against the corner of a table at day care. She started to cry and ran into the bathroom. The supervisor and assistant didn’t speak to each other for a week, and she finally quit a job she needed. If instead of thinking only of their own trying days, each had taken a minute to think about what was going on with the other (empathy), this fight could have been avoided and her job saved.

How is your empathy? Can you feel what others feel? Do you sabotage your relationships by being insensitive? Do you take the behavior of others too personally? Or instead, when someone dumps on you, do you wonder what might be going on that caused him or her to act that way? Of course, you can carry that last question to an extreme and attribute any negative criticism directed at you to someone else’s problem. Balance is the key. When negative behavior comes your way, ask yourself two questions: 1) Did I do anything to cause it? 2) What is going on with the other person? Those two questions will help you to be more sensitive to other people and improve your relationships, which will help you feel better overall —now and in the long run.

Developing empathy involves a number of important skills, including mirroring, treating others in a way you would like to be treated, and being able to get outside of yourself. The following three exercises are designed to help you increase your empathic skills.

Exercise #1: Mirroring

Your ability to understand and communicate with others will be enhanced by learning what therapists call the “mirroring technique.” You can use this technique in any interpersonal situation to increase rapport. When you mirror someone, you assume or imitate his or her body language —posture, eye contact, and facial expression —and you use the same words and phrases in conversation that the other person uses. If, for example, someone is leaning forward in his chair, looking at you intensely, you do the same without making a big point of it. If you note that she uses the same phrase several times, such as “I believe we have a winner here,” pick it up and make it part of your vocabulary for that conversation. This is not mimicry, which implies ridicule; rather, this technique allows the other person to identify with you, albeit unconsciously.

Exercise #2: The Golden Rule

Another exercise that will help you look beyond yourself and into the feelings of others is found in the New Testament book of Luke: “Do to others as you would have them do to you” (6:31). In at least one interaction per day, consciously choose to treat someone else as you would like to be treated in that situation. If your spouse has a headache when you feel romantic, for example, instead of feeling rejected, make an effort to understand. You might say something like “It must be awful to have a headache before going to bed. Can I get anything for you?” This empathetic line will get you more passion than the accusation “You always have a headache!”

Exercise #3: Get Outside of Yourself

The next couple of times you get into a disagreement, try taking the other person’s side of the argument. At least verbally, begin to agree with their point of view. Argue for it, understand it, see where they’re coming from. Although this can be a difficult exercise, it will pay off royally if you use it to learn to understand others better. In order to do this effectively, you must first listen to the opposing viewpoint without interrupting. When you do this exercise, difficult people often become less difficult. By agreeing with them, you’ll take the wind out of their sails and deflate their anger.

L IS FOR LISTENING AND GOOD COMMUNICATION

Poor communication is at the core of many relationship problems. Jumping to conclusions, trying to read minds, and needing to be right are only a few traits that doom communication. When people do not connect with each other in a meaningful way, their own minds take over the relationship and many imaginary problems arise. This can occur at home, with friends, and at work.

Donna was frequently angry at her husband. During the day, she would spend time imagining their evening together, in which they would spend time talking and being attentive to each other’s needs. When her husband came home tired and preoccupied by a hard day at work, she felt disappointed and reacted angrily toward him. Her husband felt bewildered. He was unaware of his wife’s thoughts during the day and didn’t know he was disappointing her. After a few couple’s therapy sessions, Donna learned how to express her needs up front and found a very receptive husband.

Too often in relationships we have expectations and hopes that we never explicitly communicate to our partners or colleagues. We assume they should know what we need and become disappointed when they don’t accurately read our minds. Clear communication is essential if relationships are to be mutually satisfying.

As a consultant to organizations and businesses, I have found that the underlying problem in employer-employee disputes is often a lack of clear communication. In many cases, when the communication improves, other problems are also quickly resolved.

One brief example: Billie Jo was an administrative assistant who was frequently angry at her boss. He would give her general guidelines for projects and then become irritated with her when something wasn’t done to his satisfaction. Because of his gruff manner, she was too afraid to ask him specific questions about the work. She began to really hate her job. She developed frequent headaches and neck tension and was constantly looking for another position. A friend pushed Billie Jo to tell her boss about her frustrations, saying, “If you’re going to quit anyway, you have little to lose.” To Billie Jo’s surprise, her boss was receptive to her direct approach and encouraged her to ask more questions about the projects he assigned.

Here are six keys to effective communication in relationships:

- Have a good attitude and assume the other person wants the relationship to work as much as you do. Doing so can set the mood for a positive outcome. I call this having “positive basic assumptions” about the relationship.

- State what you need clearly and in a positive way. In most situations being direct is the best approach, but the way you ask is important. You can demand and get hostility, you can ask in a meek manner and not be taken seriously, or you can be firm yet kind and get what you need. How you approach someone has a lot to do with your success rate.

- Decrease distractions and make sure you have the other person’s attention before you begin a conversation. Find a time when the person is not busy or in a hurry to go somewhere.

- Ask for feedback to ensure the other person correctly understands you. Clear communication is a two-way street, and it’s important to know if you got your message across. A simple “Tell me what you understood I said” is often all that is needed.

- Be a good listener. Before you respond to others, repeat back what you think they’ve said to ensure that you’ve correctly heard them. Statements such as “I hear you saying . . .” or “You mean to say . . .” are the gold standard of good communication. Doing this allows you to check out what you heard before you respond.

- Monitor and follow up on your communication. It’s very important not to give up.

Learn and Practice Active Listening

“I hear you saying . . . ,” or active listening, is a technique therapists are taught to increase healthy communication. This technique involves repeating back what you understand the other person to be saying, which gives you the opportunity to check whether the message you received is the one the speaker intended to convey. Communication often breaks down because of distortions between intention and understanding, especially in emotionally charged encounters.

Simply saying, “I hear you saying . . . is that what you meant?” can help you avoid misunderstandings. This technique is particularly helpful when you suspect a breakdown in communication.

Other phrases you could use with this technique include

- “I heard you say . . . am I right?”

- “Did you mean to say . . . ?”

- “I’m not sure I understand what you said. Did you say . . . ?”

- “Did I understand you correctly? Are you saying that . . . ?”

- “Let me see if I understand what you’re saying to me. You said that . . . ?”

Advantages to “active listening” include

- You receive more accurate messages.

- Misunderstandings are cleared up immediately.

- You are forced to give your full attention to the other person.

- Both parties are now responsible for accurate communication.

- The speaker is likely to be more careful with what he says.

- It increases your ability to really hear the other person and thus learn from her.

- It stops you from thinking about what you’re going to say next so that you can understand what the other person is saying.

- It increases communication.

- It tends to cool down conflicts.

When I teach active listening to parenting classes, I often use the following example: If my son came home when he was a teenager and said he wanted to have blue hair, how would I respond without the active listening skill versus with the active listening skill?

STEP 1: REACT VS. REPEAT BACK WHAT YOU HEAR

Without active listening: Just react. My father, for example, would have said, “No way as long as you live in my house are you going to have blue hair!” This only ends the conversation or starts a fight.

With active listening: Repeat back what you hear. I might say, “You want blue hair?” and then stay quiet long enough for my teen to explain.

STEP 2: STICK TO YOUR GUNS VS. LISTEN FOR THE FEELINGS BEHIND THE WORDS

My son might say, “All the kids are wearing their hair that way” (as if he had somehow taken a scientific poll).

Without active listening: My dad would likely say, “I don’t care what anyone else does; you’re not going to have blue hair. If they are going to jump off a bridge, are you going to go with them?” Again, this sets up a fight with the teen or causes him to withdraw.

With active listening: I would listen for the feeling behind the words and say, “Sounds like you want to be like the other kids.” This encourages understanding and further communication.

STEP 3: DENY YOUR CHILD’S FEELINGS VS. REFLECT BACK WHAT YOU HEAR YOUR CHILD SAYING AND FEELING

My son might say, “Sometimes I feel like I don’t fit in. Maybe changing my appearance will help.”

Without active listening: “Don’t be silly. Of course you fit in. Your appearance has nothing to do with it!”

With active listening: “You think your appearance prevents you from fitting in?”

As you can see, these are two completely different conversations. One is demeaning and limits communication, while the other promotes communication and understanding. At the end of a half hour, if my son still wants to have blue hair, I will tell him, “No way as long as you live in my house.” But at least now I know why he wants it, and he is much more likely to accept the answer.

Active listening in a relationship increases its level of understanding and communication. And when people feel understood by you, they feel closer to you. Begin practicing this technique on at least two people every day for a week. See if it doesn’t increase your communication abilities —and thus your ability to learn from others.

The Benefits of Active and Constructive Communication

When your daughter reads you her speech, which she is scheduled to deliver at school the next day, and asks for your opinion, how do you respond? How about when your spouse wants to tell you about his day at work? As we have seen, the way you communicate with others can help or hurt your relationships. Studies have shown that a technique called active and constructive communication can quickly strengthen your relationships and improve your mood.[169]

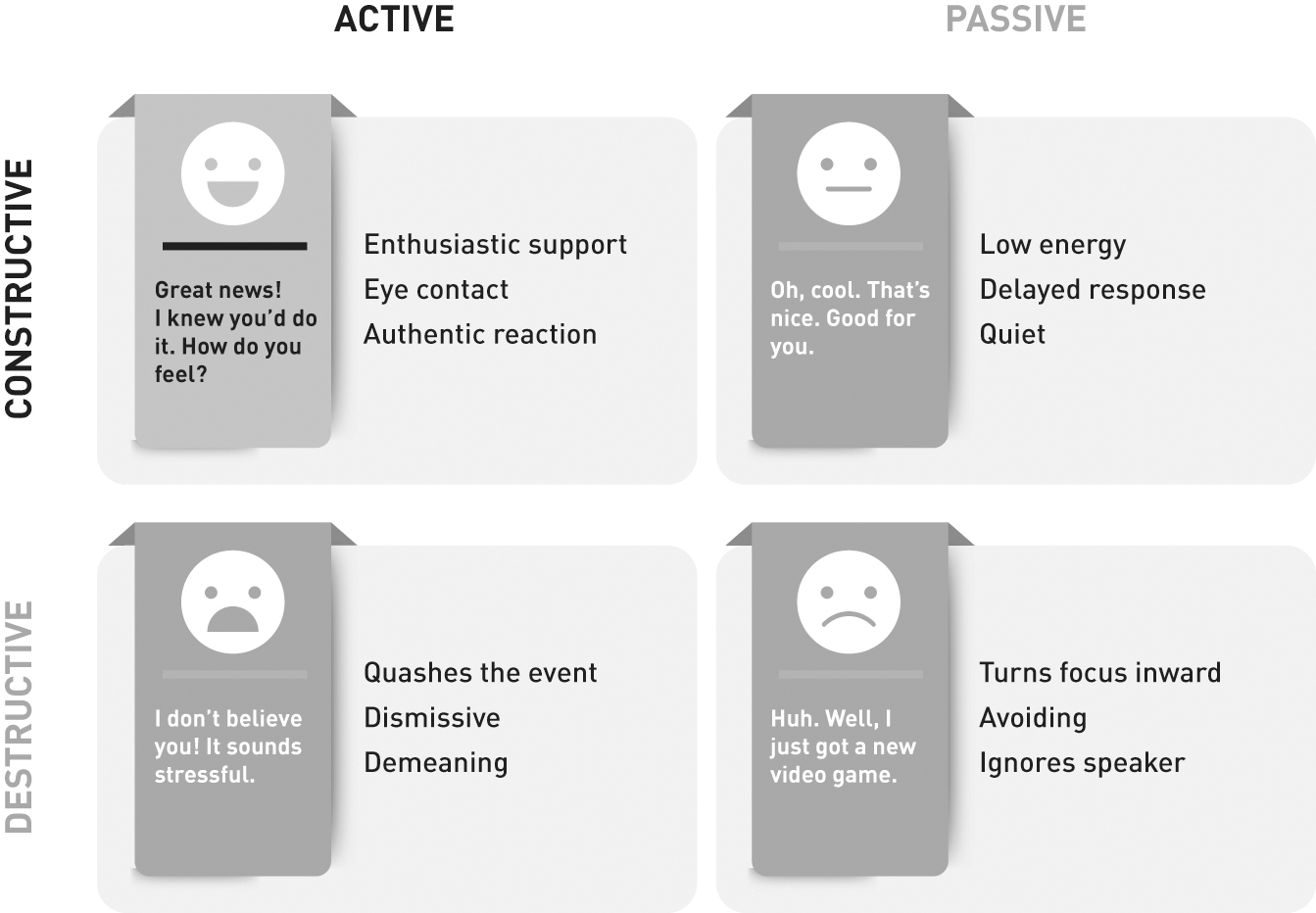

Marty Seligman and his colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania have written about four typical styles of communication:

- Active and Destructive: pointing out negative aspects of a situation

- Passive and Destructive: ignoring the person completely

- Passive and Constructive: supporting someone but in an understated way

- Active and Constructive: giving both authentic and enthusiastic support[170]

If you want to improve your relationships, research shows that active constructive communication works, while the other styles do not. Let’s say your daughter just got her first acting audition. Here are examples of how you could respond:

- Active and Destructive: “That is such a hard profession. Why would you ever want to do that?”

- Passive and Destructive: Little to no response.

- Passive and Constructive: “That’s nice.”

- Active and Constructive: “Wow! That’s amazing. Congratulations! Tell me all about it.”

Use active constructive communication when responding to someone.

Communicating actively, positively, and constructively helps us build positive relationships and enhance self-esteem.[171]

FOUR TYPICAL COMMUNICATION STYLES

A IS FOR ASSERTIVENESS

Assertiveness involves standing up for one’s rights without infringing upon those of others, whereas aggression involves the use of verbal and nonverbal noxious stimuli to maintain rights.

DRS. MARSHA RICHINS AND BRONISLAW VERHAGE

In healthy relationships it’s important to say what you mean. In that way, assertiveness and communication go hand in hand. Being assertive means you express your thoughts and feelings in a firm yet reasonable way, not allowing others to run over you emotionally, and not saying yes when that’s not what you mean. Assertiveness never equates with being mean or aggressive.

Here are five simple rules to help you assert yourself in a healthy manner:

- Do not give in to the anger of others just because it makes you uncomfortable. Anxious people do this a lot. They are so anxious that they agree in order to avoid the tension. Unfortunately, doing this teaches others to bully you to get their way. We teach others how to treat us by what we allow in our lives. Being assertive in the face of another’s anger doesn’t mean you have to be angry back, but it does mean you don’t agree with someone simply because you’re uncomfortable. When you are feeling anxious about another person’s anger, it is a good time to do the deep breathing techniques I taught you earlier (see chapter 1, page 17). Take three deep, slow breaths and really think about what your opinion is; then state it clearly without much emotion.

- Say what you mean and stick up for what you believe is right. People will respect you more. People like others who are real and who say exactly what’s on their minds.

- Maintain self-control. Being angry, mean, or aggressive is not being assertive. You can be assertive in a calm and clear way.

- Be firm and kind, if possible. Above all, be firm in your stance. Again, we teach other people how to treat us, so when we give in to their temper tantrums, we actually teach them the way to control us. When we assert ourselves in a firm yet kind way, others have more respect for us and will treat us accordingly. Now, if you’ve allowed others to emotionally run over you for a long time, they’re going to be resistant to change. If you stick to your guns, you will help them learn a new way of relating to you, and the relationship will improve. Ultimately, you also will respect yourself more.

- Be assertive only when it is necessary. If you assert yourself all the time for unimportant issues, you’ll be perceived as controlling, which invites oppositional behavior.

T IS FOR TIME

Relationships require actual, physical time. In this era of commuting, traffic, two-working-parent households, e-mail, the Internet, television, and video games, we have seriously diminished the time we have with the people in our lives. Spending actual, physical time with the people who are important to us will make a huge difference in our relationships. When I teach the parenting course we give at Amen Clinics (one of the most effective things I’ve ever done to help children), I say that relationships really require just two things —time and a willingness to listen. Focused time, even if there’s not a lot of it, is critically important to relationships.

Special time. I teach an exercise in my parenting course called “special time,” which involves spending 20 minutes a day doing something with your child that he or she wants to do. Twenty minutes is not much time, but this exercise makes a huge difference in the quality of your relationships. I have one rule for this exercise: no commands, no questions, and no directions. It’s not a time to try to resolve issues; it is just a time to be together and do something your child wants to do, whether it’s playing a game or taking a walk. The difference it made in parent-child relationships was much more dramatic than anything else I did for them, including prescribing medicine. Look for ways to spend time with the people who are important to you. Think of this time as an investment in the health of the relationship.

In a similar way, be present when you are spending time with others at work or at home. We encounter so many distractions that we are rarely present anywhere we are. In the powerful book Influencer: The Power to Change Anything, the authors tell a story about a large health care organization that went from having terrible customer satisfaction to becoming one of the region’s first-class organizations. In studying the employees who ranked “great” versus those who were “poor,” the researchers found only five simple differences. The effective employees

- Smiled

- Made eye contact

- Identified themselves by name

- Let people know what they were doing and why

- Ended every interaction by asking, “Is there anything else you need?”[172]

These things were easy to do, and they indicated that the service providers were present and focused on the interaction at hand. Being present in the moment with your spouse, friend, or colleague can help make the other person feel appreciated and secure.

I IS FOR INQUIRING

Earlier in the book we discussed eliminating the ANTs (automatic negative thoughts) that invade your mind. When you’re suffering in a relationship, it’s important to inquire into the thoughts that are making you suffer. Ask yourself what thoughts are repeatedly going through your mind, and then consider how accurate they might be. If you are fighting with your husband, for example, and you hear yourself thinking He never listens to me, write that down. Then ask yourself if it is true: Does he really “never” listen to you? Often when we tell ourselves little lies about other people, it puts unnecessary wedges between us and them. Relationships require accurate thinking in order to thrive. Whenever you feel sad, mad, or nervous in relationships, check out your thoughts. If there are ANTs or lies, stomp them out.

N IS FOR NOTICING WHAT YOU LIKE

Noticing what you like a lot more than what you don’t like is one of the secrets to having great relationships. Paying attention to what you like encourages more of that behavior. I learned this concept for the first time when my son was seven years old and we were living in Hawaii. I was in my child psychiatry fellowship-training program.

One day I wanted to have special time with my son, so I took him to a place called Sea Life Park, which is like SeaWorld. We had a great day together. We went to the orca show and the dolphin show, and we saw sea lion antics onstage. Toward the end of the day my son sort of grabbed my shirt and said, “Daddy, take me to see Fat Freddie.” I said, “Who’s Fat Freddie?” “It’s the penguin, Dad,” he said. Fat Freddie was an emperor penguin who performed in the large stadium at Sea Life Park. I looked on the show schedule and saw there was one more Fat Freddie show that day. When we got to our seats, the stadium was filled.

Freddie was amazing. To start the show, he climbed a ladder to a high diving board. He went to the end of the board, bounced up and down, and then jumped into the water. When he got out of the water, on command he bowled with his nose, counted with his flippers, and jumped through a hoop of fire. I was thinking to myself, How cool is this? My son was clapping, very happy that we were at the show. Toward the end, the trainer asked Freddie to go get something. Freddie immediately brought it to the trainer. When I saw this, I thought, I ask this kid to get me something, and he wants to have a discussion for 20 minutes, and then he doesn’t do it. I used to find myself frequently frustrated and angry at my son, but I knew he was smarter than the penguin.

After the show I went up to the trainer and asked her how she got Fat Freddie to do all the things he did. The trainer understood what I was asking her, because she looked at my son and then she looked at me and said, “Unlike parents with their kids, I notice Freddie whenever he does anything like what I want him to do. I give him a hug and a fish.” The light went on in my head: Whenever my son did what I wanted him to do, I paid no attention to him because I’m a busy guy. But when he didn’t do what I wanted him to do, I gave him a ton of attention because I didn’t want to raise bad kids. I was inadvertently teaching him to be a little monster in order to get my attention. I started collecting penguins to remind myself to notice what I like about others more than what I do not like. I now have more than 2,000 penguins.

What do you think Fat Freddie would have done if he was having a bad day and didn’t do what the trainer asked him to do? Imagine if, all of a sudden, the trainer started screaming at him, “You stupid penguin. I can’t believe I ever met a penguin as stupid as you. We ought to ship you off to the Antarctic and get a replacement.” Depending on his temperament, if he understood her, Fat Freddie would have either bitten her or gone off to a corner and cried.

What do you do when the important people in your life do not do what you want them to do? Do you criticize them and make them feel miserable? Or do you just pause and decide to notice what you like more than what you don’t like? This is a critical point that’s important for changing behavior: Focus on the behaviors you like more than the behaviors you don’t.

It turns out there is also a great deal of science behind this concept:

- A marriage with five times more positive comments than negative ones is significantly less likely to result in divorce.

- A business team with five times more positive comments than negative ones is significantly more likely to make money.

- College students who receive three times more positive comments than negative ones are significantly more likely to have flourishing mental health.[173]

The amount of positivity in a system divided by the amount of negativity is called the Gottman ratio after marital therapist John Gottman, who discovered that the number of positive comments to negative ones significantly predicts marital satisfaction and the chances of staying together versus getting divorced. It is also called the Losada ratio after Marcial Losada, who applied Gottman’s ratio to the workplace. Keep in mind that balance is important. When comments are too positive, they lose their impact, especially if the ratio is above nine.

G IS FOR GRACE AND FORGIVENESS

Amazing grace! How sweet the sound

That saved a wretch like me!

I once was lost, but now am found;

Was blind, but now I see.

JOHN NEWTON, “AMAZING GRACE”

Forgive us our sins, as we have forgiven those who sin against us.

MATTHEW 6:12, NLT, FROM THE LORD’S PRAYER

The first definition of grace in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary is “unmerited divine assistance given to humans for their regeneration or sanctification.”[174] It is a gift from God that we do not deserve. Grace and forgiveness go hand in hand. One of the most famous prayers in history commands us to forgive others if we ourselves want to be forgiven. Forgiveness is powerful medicine. Holding on to grudges and hurts, even if they are small, increases stress hormones that negatively impact our moods, immunity, and overall health. Giving grace and forgiveness can be hard, but when done properly it can also be powerfully healing. Research has linked forgiveness to mental health outcomes such as reduced anxiety, depression, and major psychiatric disorders, and with having fewer physical health symptoms and lower mortality rates.[175] I often tell my patients that the person who forgives also usually ends the argument.

Grace and forgiveness do not mean letting someone off the hook or condoning bad behavior. They are not the same as justice and do not require being reconciled with the person who has given offense or done harm. More often than not, a former victim of abuse should not reconcile with the abuser, especially if the abuser has not sought serious help. Grace and forgiveness are acts of strength, not weakness.

Psychologist Everett Worthington of Virginia Commonwealth University has studied forgiveness for years and developed a model called REACH forgiveness, which stands for

- Recall the hurt —This time recall it differently, without feeling victimized or holding a grudge. This moves you toward relating to the offense from the point of view of the offender.

- Empathize —Replace negative emotions with positive, other-oriented emotions. This involves empathizing —putting yourself in the shoes of the person who hurt you and imagining what he or she might have been feeling.

- Altruistic gift —Give the gift of your forgiveness to the person who hurt you. Think about a time in your past when you wronged someone and that person forgave you; remember how much freer you felt afterward. That freedom is your gift to your offender.

- Commit to the forgiveness that you experience —When you have forgiven, write a note to yourself about it. You can also cement your feelings by engaging in a ritual, such as completing a forgiveness certificate or writing a word symbolizing the offense in ink on your hand and then washing it off.

- Hold on to the forgiveness —If or when you encounter the offender, you may feel anger and fear, and you may worry that you haven’t really forgiven him or her. But that is just your body’s response as a warning to be careful. Reread your notes to remind yourself that you have laid aside the offense.[176]

In 1996, Dr. Worthington’s research was put to the worst possible test: His mother was murdered in a home invasion. Although police believed they had found the murderer, he was never prosecuted. Despite the awful tragedy, Dr. Worthington said, “I had applied the forgiveness model many times, but never to such a big event. As it turned out, I was able to forgive the young man quite quickly.” This is an amazing testimony to the power of forgiveness.

Is there someone in your life who needs your grace, whom you could forgive? It may help you feel better. Just keep in mind that forgiveness is usually not a quick process. The REACH forgiveness model, for example, focuses on changing from the inside, which can take time. (To see a presentation on this topic from Dr. Worthington, search YouTube for “Helping People Reach Forgiveness —Everett Worthington.”)

My wife, Tana, tells a story about her involvement in a brain health program we were asked to develop for the Salvation Army’s largest chemical addiction recovery program. She helped re-create the food portion of our plan for the participants. After her first visit to the campus, she was suddenly filled with horrible, judgmental thoughts about the addicts in the program. It’s clear that clean eating helps people with addictions make better decisions, so she wanted to participate. But how could she help people who brought up feelings of fear and loathing inside her? Most of the participants (beneficiaries) are court ordered to be in the program, and many go there after having served time in jail for some pretty serious criminal offenses.

Growing up, Tana directly experienced the consequences that drugs can have on people’s lives. Her uncle was murdered in a drug deal gone wrong. She hated drugs and had no tolerance for anyone who used them. When she told me she didn’t think she could follow through with helping at the Salvation Army, that God had picked the wrong person this time, I smiled and said, “God picked the perfect person.” I was right. Working with that population gave Tana new empathy for the clients’ backgrounds, which were not that much different from her own. And she realized that for every person she helped who was a parent, there would be one less scared child in the world.

The eight keys we’ve discussed in this chapter will improve almost any relationship. Being responsible and empathic, listening, being assertive, spending time, inquiring into negative thoughts, noticing what you like more than what you don’t, and giving grace and forgiveness are tools you can use today to bring those in your life closer to you.

THE BRAIN AND RELATIONSHIPS

In addition to developing great habits to help people connect, our brain imaging work has taught us that the physical functioning of the brain is an often-overlooked component of why relationships succeed or fail. Over the past three decades I have scanned hundreds of couples who have had serious marital problems. In my training as a marital therapist, and in the training of almost all marital therapists on the planet, there was not one lecture on how the physical functioning of your brain impacts the relationship. Yet, since your brain is involved in everything you do and everything you are, if it doesn’t function right, you are likely to have significant problems relating to people you care about. At Amen Clinics, we look at relationships and relationship conflict in a whole new way, involving compatible and incompatible brain patterns. I have come to realize that many relationships do not work because of brain misfires that have nothing to do with character, free will, or desire. Many relationships are sabotaged by factors beyond conscious or even unconscious control. Sometimes a little targeted brain intervention can make all the difference between love and hate, staying together and divorce, effective problem-solving and prolonged litigation. See my book Change Your Brain, Change Your Life for a detailed look at this topic.

EIGHT STRATEGIES TO ENHANCE YOUR ABILITY TO CONNECT BY RELATING

- Ask yourself if you are taking RESPONSIBILITY in your relationships: “How can I respond in a positive, helpful way?”

- Practice EMPATHY: Treat others as you would like to be treated.

- In conversations, LISTEN and practice good communication skills.

- Be ASSERTIVE: Say what you mean and stick up for what you believe is right in a calm, clear, kind way.

- Spend TIME: Remember that actual, physical time with others is critical to healthy relationships.

- INQUIRE into the negative thoughts that make you suffer in a relationship, and decide if they’re true.

- NOTICE what you like in the behavior of those around you more than you notice (and complain about) what you don’t like.

- Give the altruistic gift of GRACE and forgiveness whenever you can.

TINY HABITS THAT CAN HELP YOU FEEL BETTER FAST—AND LEAD TO BIG CHANGES

Each of these habits takes just a few minutes. They are anchored to something you do (or think or feel) so that they are more likely to become automatic. Once you do the behaviors you want, find a way to make yourself feel good about them—draw a happy face, pump your fist, or do whatever feels natural. Emotion helps the brain to remember.

- After I’ve had a fight with a loved one, I will take responsibility for my part and apologize (responsibility).

- When someone acts negatively toward me, I will ask myself, Did I do anything to cause it? What is going on with this person? (empathy).

- When I am in a conversation with someone, before responding with my input, I will reflect back what I heard him or her saying (active listening).

- When I am challenged or bullied, I will state the case for what I believe, calmly and clearly (assertiveness).

- When I set aside time to be with my child, I will spend 20 minutes doing whatever he or she wants to do, with no agenda (time).

- When I have a negative thought about my spouse, such as He never listens to me, I will write it down and ask myself, Is that true? If it is not, I will quash the thought (inquiry).

- When a friend does something annoying, I will turn my attention to the things I like about her rather than dwelling on the annoyance (noticing).

- When someone is mean or hurtful to me, I will try to create grace in my heart to forgive them (grace and forgiveness).