The National Aeronautics and

Space Administration

On a bright fall day in 1984, an architect was taking a drive through the American Midwest, headed for Indianapolis in order to talk about living in space. He had been making these trips regularly, from his home base in Cleveland, where he had just recently retired from his lifelong career at the Glenn Research Center. Jesse Strickland was hired in 1950 at what was then known as the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory, part of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), a notable achievement for a Black man at that time. He eventually became chief architect of the entire facility under the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which absorbed the earlier organization whole in 1958.

A lot of things changed over the course of Strickland’s career. By the time he had left there was not a single building on the Glenn campus that he had not had a hand in designing. In addition to his work as an architect, he was a passionate advocate for community building, education, and mentorship and served as the coordinator of a NASA job training program that offered opportunities and advising for adult students returning to high school to finish their degrees. He always reached out to new hires at Glenn/Lewis, but especially to new Black colleagues, taking them around to introduce them, and offering an open door to their concerns and questions. Eventually he was formally appointed to serve as one of Glenn’s equal employment officers, who handle any discrimination complaints at the center.1

Naturally for an architect working at NASA, he was deeply interested in space science and spaceflight, and he was a long-time advocate for Gerard O’Neill’s space settlement proposals. While working at Glenn, he was part of NASA’s “Speakers Bureau,” who are, in NASA’s own words, “engineers, scientists, and other professionals who represent the agency as speakers at civic, professional, educational and other public venues.” These outreach and education responsibilities are highly valued within the organization, and Strickland’s particular warm brilliance and wit kept him in high demand. During and after his tenure at Glenn, Strickland enjoyed traveling throughout the Midwest to speak at universities, supper clubs, and gatherings of space enthusiasts about NASA, spaceflight, and, in a talk he gave several times called “Life beyond Earth,” the possibility of a long-term human future in space.

The title of Margot Lee Shetterly’s 2016 book Hidden Figures (and the film from the same year) refers to the Black women who were literally “computers.” In the middle of the twentieth century, the word was used to describe the workers who did the calculations—by hand—that rationalized the complexities of spaceflight, orbital mechanics, and rocket science. Katherine Johnson, one of the book’s main subjects, based at the Langley Research Center in Virginia, worked on the math behind Alan Shepard’s ballistic flight to space and back in 1961. The next year, John Glenn was launched on a more complicated trip. This was an attempt to match the historic accomplishment that cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin and the Soviet space program had already achieved: reaching stable Earth orbit with a crewed spacecraft. By this time, the flight calculations were sometimes done by electronic “computers,” not always human women in NASA offices, but Glenn wanted them double-checked. “Get the girl,” he told his flight controllers, and they asked Katherine Johnson (who was forty-four at the time) to run his numbers again.2

The importance of Black women to the history of American spaceflight had been, if not deliberately hidden, at least forgotten. Johnson only received national recognition for her work in the 2010s, and despite the crucial role she continued to play in the Apollo and Space Shuttle programs, she was never a member of the Speakers Bureau or any other public-facing aspect of NASA’s work in the late twentieth century. At this writing, some ten months after Katherine Johnson’s death in February 2020 at the age of one hundred and one, her name is practically a household term. However, the formerly prominent Jesse Strickland is unknown, even within space science circles.

The relative prominence and obscurity of figures like Johnson and Strickland are symptoms of a complicated situation in which the agency has found itself ever since its inception. NASA needs visibility in order to exist and work, but the presentation of clear images of its own aspirations has gotten the agency in trouble over the course of its existence, as seams between the hopes for the future and the conditions of the present also become apparent. A public entity, NASA is the world’s most prominent space agency, and it is arguably the organization with the most capabilities involving human spaceflight. But those capabilities need visibility if they are going to continue to be publicly funded. NASA needs images of its possible and best self, and its possible and best future. NASA depends on (and produces) a complex set of systems—technical, social, and political—and it also depends on images that make this complexity legible, sensible, and comprehensible.

Visible Figures

The Cold War and the space race had to do with more than the material threats posed by new technologies; they also turned on the use of images to demonstrate technical capability and build power. Although the stories and visuals from this period, and from the exploration of space generally, have a lot to do with engineering, they are bound up in the production of political and social life as well. Sputnik 1, for example, launched into orbit in 1957, was not only a scientific experiment that was part of the International Geophysical Year; it was also a performance. The satellite was highly polished for maximum visibility in the night sky, and its unique spherical form, with four radio antenna broadcasting beeps on a publicly available frequency, is iconic and widely recognized around the world as a symbol of the space age.

Eisenhower was likely aware that the Soviets had been developing the technical capability for the satellite launch, as well as the fact that Russians were tracking the United States’s own programs, one of which was led by Wernher von Braun. The Americans did not seem in a rush, knowing that relative parity existed between the two nations. This failure to attend to the visibility and impact of the image was a mistake the American space program would not continue to make much longer. Many of the images of an American spacecraft that the public saw over the next weeks showed it exploding on the launch pad. And the next image that global audiences saw associated with the Soviet program was of a smiling, alert adolescent dog. Laika was launched into orbit only a month after Sputnik 1, on the fortieth anniversary of the October Revolution. After Yuri Gararin’s handsome, innocent, socialist face was on the cover of every newspaper in the world, the United States space program quickly learned to produce better visuals. Photos of John Glenn, an energetic young white man with an ironic smile, a buzz cut, and a silver spacesuit, would do the job nicely.

The two superpowers were staging these demonstrations not only for one another, but for a world audience of the colonized, the influenced, the allied, and the neutral. What was at stake here was planetary imagination and hegemonous tectonics—the composition of the world from its component states and pieces into different kinds of empires and economies.

The “Earthrise” photograph from Apollo 8, the first trip to Lunar orbit, has been cited by everyone from ecologists to cyberneticians as the first example of an all-encompassing image that presents Earth as a whole system. Complexities collapse into the immediate impact of this picture. The almost-religious feeling of awe and peace, the “overview effect” discussed in chapter 3, is here. But, as science and technology scholar Jordan Bimm points out, it matters who is doing the seeing.3

The American and Soviet imaginations about a whole Earth were very different from one another. The Moon landings of the Apollo program were not faked, but, as historian Nicholas de Monchaux points out, they were deliberately designed to produce and broadcast a very specific image to the world, for a very specific purpose. As de Monchaux shows, the complex technical networks behind and inside the Apollo space suit and spacecraft were made both prominent and hidden by the capture and mass reproduction of the famous image of Buzz Aldrin on the Lunar surface.4

This was probably the most effective, and most reproduced, image of a human in space since the iconic photos of cosmonaut Alexei Leonov’s first spacewalk in 1965. On that same trip, Leonov, himself a lifelong image maker, became the first person to make art in space: a colored pencil drawing of a sunrise, made with materials he had brought himself. This was a sketch that he elaborated on again and again over the course of his life. He also painted multiple versions and views of his famous spacewalk. If the Soviet plans had gone better, that photo of a human on the Moon might have shown Leonov instead. He was meant to follow up his walk in space with a walk on the Lunar surface, which would have made for a tidy narrative end to the space race.

Instead of another trip outside, it was a trip inside that bracketed the competition between these countries and their space agencies. In 1975, six years after Aldrin was photographed on the Lunar surface, the Soviet and American space programs collaborated on an unprecedented project. Fulfilling a few hints that President Kennedy had floated during the previous decade—indicating they might work together to get to the Moon—the two countries launched the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. The Soviet and American spacecraft met in orbit, where they docked for forty-four hours, and the crews shared food and living space together. Leonov was commander of the Soviet mission, and he drew a portrait in space of his American counterpart.5 The mechanical and tectonic means for this operation, the jointly developed Androgynous Peripheral Attach System, is the ancestor to the docking collars used today on the International Space Station, where American collaborations with space agencies from Russia and other nations continue.

There were other applications of images and tectonics along the way to this finale, and many Soviet wins in the narrative wars. Seeing a weakness in the United States’ image as an warmongering imperial actor abroad, and as a perpetuator of inequality and injustice at home, the Soviets pushed their advantage, both before and after the Moon landings. They launched the first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova, in 1963. And in 1980 they flew the first person of African descent, Cuban Arnaldo Tamayo Méndez, on Soyuz 38, on a mission to the Salyut 6 space station. The Soviet Union used the opportunity to fly its first (and so far, only) Black cosmonaut as partly a way to shore up connections with an external ally and client state.

The Americans would also have to address their own internal seams and fissures in some way. NASA did not launch a Black astronaut until three years later, when Guion Bluford flew on board the shuttle Challenger as part of STS-8. Outside of the astronaut corps, NASA recognized the need to keep up with equity, and the propaganda value of global perception, early in this regard. As Shetterly notes in Hidden Figures, even before NACA became NASA, the agency’s chief legal counsel wrote a memo that read, in part: “Eighty percent of the world’s population is colored … In trying to provide leadership in world events, it is necessary for this country to indicate to the world that we practice equality for all within this country.”6

In order to compete for allyship abroad, and to maximize those who might potentially accept American “leadership,” the United States had to modify its own internal composition, integrating portions of itself that had been divided. Therefore, NASA began to desegregate before the 1964 Civil Rights Act made the older tectonic doctrine of “separate but equal” unconstitutional. But tectonics is about the abstract expression of concepts as well as built reality. This was as much about the indication of a practice as it was about the practice itself.

NASA’s desegregation opened up opportunities and difficulties for staff like Katherine Johnson and Jesse Strickland. Both had already been hired by the time NASA officially ended their own “separate but equal” policies with regard to spatial arrangements on their campuses. The ongoing struggles faced by Johnson and her colleagues to realize equal access to bathrooms, lunchrooms, and other public spaces at Langley are well documented in Shetterly’s book. One can only imagine the complicated feelings that Strickland must have been processing when he worked on the design of cafeteria renovations and upgrades at Glenn/Lewis, unifying spaces in which he himself had previously sat separately from friends and coworkers.

Still more difficult must have been the experiences of Black staff at the Marshall Spaceflight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, who were attempting to navigate desegregated space on the center’s campus in the early 1960s, while students were staging sit-ins at still-segregated lunch counters on the town’s main street. It was not only the case that their director, former Nazi SS officer Wernher von Braun, was busy overseeing the design of the Saturn V rocket, but almost the entire leadership team at NASA’s Huntsville Center had also been involved in the design of the V-2—that ancestor of the Saturn that had been assembled by enslaved prisoners, at the cost of tremendous suffering and loss of life.

No Black astronaut ever ended up flying on the Saturn V rocket that von Braun and his team of German rocket scientists made; only one came even close. In 1961 Ed Dwight was selected as the first Black astronaut trainee. Despite making it to level two of the rigorous training process, Dwight was not selected to be an astronaut, a decision he blames on racial politics; an assistant to President Kennedy had recommended his inclusion in training “for symbolic purposes.”7 Dwight’s career as an astronaut candidate seems to have been doomed from both sides. On the one hand, there were those who enthusiastically used his candidacy as an image of a possible future for Black students in science and engineering, only to cynically discard advocacy on his behalf when he was (almost inevitably) passed over. On the other hand, there were those, like would-be luminary test pilot Chuck Yeager, who went out of their way to disparage his qualifications and dismiss him as a token.8

Somewhere in all of this image making, receeding behind the layers of narrative, there is Dwight the person. In the years since he left astronaut training, Dwight has had an eclectic career, spending time as a restaurateur and property developer. Today, he is an image maker himself, a prolific public sculptor whose decades of work have focused exclusively on civil rights themes. He is well aware of the fluidity of interpretation that his engagement with imagery can elicit. As he told the Guardian in 2015, “My work is really just about the flow of ironies.” And he is cognizant of the ways in which he can represent the seams and tectonics of political life to various audiences who are seeing different things, sometimes even a different overview:

“There’s always a fine line that divides hostility from neutrality, and I don’t want to pass that line,” Dwight says from his studio in Denver, Colorado. “But sometimes the happy endings on my sculptures have two meanings: the white folks come away thinking ‘Hey, we fixed something; things are now cool,’ while the black folks know we transcended, that we overcame; we won the game.”9

The first Black American to complete astronaut training and be selected as an astronaut was Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. A test pilot with a PhD in chemistry from Ohio State, Lawrence did not view his achievement as a particularly symbolic act, but rather as a part of what should be expected as social change continued to occur—“normal progression,” in his words.10 Lawrence was formally selected in June of 1967, but in December of that year he died in a plane crash, while teaching another air force pilot one of the sophisticated flying maneuvers he was so well known for.

Another Black astronaut from Lawrence’s generation, Livingston Holder Jr., lost his chance to fly in space during the nearly three-year hiatus in Space Shuttle launches after the 1986 Challenger explosion. That disaster also killed Black astronaut Ronald McNair, who had been to space once already, on a previous Challenger mission. No official reason is given in their biographies for the fact that two other Black astronauts, Michael Belt and Yvonne Cagle, never flew in space. Belt has since retired, but Cagle still works at NASA, although she is no longer eligible for flight. Like Jesse Strickland, Cagle is a frequent speaker on NASA’s behalf, and an enthusiastic advocate for a human future in space.

In total, as of this writing, fifteen of the 339 Americans who have flown in space were Black, including Charles Bolden, who later went on to serve as the head of NASA for eight years. Mae Jemison, the first Black woman in space, is also a member of the same generation as Lawrence. Famously, Jemison was inspired to become an astronaut at an early age by the character Lieutenant Uhura on the original Star Trek TV series. Uhura’s character, played and developed by Nichelle Nichols, was a groundbreaking role at the time, and part of show creator Gene Roddenberry’s agenda to use the show’s future, off-world setting to demonstrate visibly that a more just and diverse universe was possible. Nichols was talked out of quitting the show after the first season by none other than Martin Luther King Jr. himself, who told her, “You are our image of where we’re going.”11

Despite King’s optimism, there is a long gap in the history of Black spaceflight that has only recently closed. In the period during the construction of the International Space Station, NASA was regularly flying one Black astronaut a year on average. That pattern ended abruptly with the closure of the Space Shuttle program in 2011. During the subsequent nine-year interval in which the American space program relied on Russian hardware, launch infrastructure, and the robust Soyuz spacecraft to get to space, no Black astronauts went along.

NASA has not offered any explanation for this lapse, or for the sudden reassignment of Black astronaut Jeanette Epps in 2018, who had been due to catch a ride to the space station on a Russian Soyuz later that year. A white astronaut was placed in her seat instead, only two weeks after the mission was announced. An uncredited story in the state news agency Russia Today responded to insinuations that some unspoken racist policy within the Russian space agency Roscosmos was to blame for the gap by invoking Russia’s earlier, highly visible gesture of inclusion, pointing out: “The first person of African heritage in space was Arnaldo Tamayo Mendez of Cuba, launched in 1980 by the Soviet Union. NASA sent the first African-American astronaut, Guion Bluford, three years later.”12 NASA itself, however, kept any imagery or narrative closed on this issue. These figures were again hidden. Regarding Epps’s reassignment, a NASA spokesperson said, “These decisions are personnel matters for which NASA doesn’t provide information.”13

Signaling the Artist’s Impressions

In 2015 I visited NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley. I was there to see their archives, which contain several painted renderings made by artist and architect Rick Guidice for a series of Summer Studies hosted by Ames, including the 1975 Study on Space Settlement, led by Gerard O’Neill. I was also there to interview Guidice, who was seeing many of the paintings for the first time in decades. Our host was Ames Archivist April Gage.

After discussing the work that was part of the collection she oversaw, Gage invited us to take a walk to another part of the Ames campus, where two paintings from O’Neill’s 1975 Summer Study were hanging in an open plan office area. One shows the interior of a “Stanford torus” model habitat, shaped like gigantic spinning bicycle wheel, a mile in diameter. The viewpoint is from a terrace patio, looking down into a valley with sports fields, bike paths, and farms. The other side of the valley is built up with more terraced housing and shops. A couple are talking and leaning against the railing, still in tennis clothes from a game that had just wrapped up.

The other shows the interior of an equally large “Bernal sphere,” named in honor of the work of J.D. Bernal. Even though the sphere is rotating to provide artificial gravity inside, this doesn’t seem to bother the woman hang-gliding through the sky, with more houses and parkland visible in the distance, upside-down behind her. The foreground includes a lively cocktail party, where one of the guests is a smiling Black woman with an afro. These two paintings were part of a suite of thirteen renderings made for the 1975 Summer Study, and published by NASA, O’Neill, and others to promote the project. About half of these were painted by Guidice, and half by another artist mentioned earlier, Don Davis, who had gotten his start making illustrations for the (then relatively new) field of planetary science, working with Carl Sagan and others.14

While the three of us were examining the two paintings hung in the conference area and talking, a member of the NASA staff who worked in the office, as part of a team developing satellite missions, approached shyly. The NASA staffer wanted to meet Guidice, and to tell him how important it had been over the years to have his paintings in the office: “These provide real inspiration to us while we’re working!” Guidice credits his dual backgrounds in commercial art and architecture for giving him the skills necessary to use imagery like this to sell a product or a project.

The two paintings by Guidice had been hung in the satellite mission development office a few years earlier by Alexander MacDonald, then the center’s first research economist, and were intended to provide exactly the sort of inspiration that the staffer reported. The two paintings were eventually acquired by Gage’s office and are now an official part of the Ames archive; they have most recently been shown at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.15

Many historical narratives about the space race focus on the desire of the two major participants, the Soviet Union and the United States, for “prestige” on the global scene. In his work as a historian of space exploration, MacDonald, now chief economist at NASA, prefers to apply a lens that is both more general and more specific to describe the motivations and functions behind and in front of national space programs and space exploration. For MacDonald, as he lays out in his 2017 book, The Long Space Age, “prestige”—the accumulation of admiration, respect, and not a little fear in the international arena, by way of the display of technical prowess—is only a subset of a larger category, borrowed from biology and economics, “signaling.”16

Signaling, for our purposes, is the demonstration of a capability; sometimes those capabilities are aspirational, while other times they are achievable. Prestige is a kind of signal that acts from one state to another. The achievement of “firsts” in space is a signal from one superpower to another, but also to all of the other potential client states or trading partners, that the achieving nation is capable of feats that require extraordinary amounts of economic capital, technical skill, and group coordination. The highly public nature of an act like landing an American on the Moon lends credibility to the implicit claim that the American state is making to other nations: “We are the kinds of people who are able to do things like this.”

Space exploration is supported by a whole layer of rhetoric around and beneath it, and there are other types and scales of signaling going on at the same time. MacDonald discusses a 1958 document prepared for President Eisenhower, “Introduction to Outer Space,” that lays out four primary motives that argue in favor of expenditures in the space race: exploration, defense, prestige, and science.

Wernher von Braun was a figure who was especially skilled at moving between these four regimes, and code-switching between the different signaling modes they require. Von Braun told a press conference, on the eve of the Apollo 11 launch, that a first trip to the Moon was an act of exploration and discovery equal to the first time a sea creature had stepped on land. In Collier’s magazine, in his book The Mars Project, and in private presentations before generals and other government officials, however, he had stressed the military and defense benefits of being first in space. He discussed the issue of national pride and prestige with four presidents: Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon. And on television with Walt Disney in the 1950s, he had taken pains to point out the necessity of advancing science by going to space to an audience of impressionable Baby Boomers.

States signal to other states, but states, agencies, and individuals like von Braun also signal internally to audiences of other individuals, saying explicitly: “We are the kinds of people who want to do things like this.” In this way, they imply that sympathetic audiences should support, if not join, those efforts, if they are those kinds of people, too. In the 1970s and ’80s, this kind of signaling, from the space agency to groups of individuals, took place partly through the series of Summer Studies. Formally (and more ponderously) known as the NASA-ASEE Summer Faculty Workshop in Engineering Systems Design, the program began throughout the agency in 1964 and ended at Ames in 1996, although similar programs continued at other NASA research centers, like the Johnson Space Center in Houston. The beginning and ending of the program took place in relative obscurity, but the period in which Ames retained Rick Guidice to illustrate their Summer Studies reports produced work that is still sending influential signals today, in space science and in popular culture.

Some of the topics seem relatively quotidian, like laboratory optics (1972), fire management (1974), or “planning for airport access” (1978). But the exciting themes were right out of Usborne and science fiction, and they were always the ones illustrated by Guidice.

For the study on Project Cyclops in 1971, which proposed a huge array of 1,000 radio telescopes in the American desert to listen for alien signals as part of SETI, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence, Guidice painted an aerial view of the facility, in which each of the thousand dishes stands out individually, while together they form a miles-wide circle in the desert, with mountains visible in distant haze. He also painted a ground-level view of the proposed facility, with an operations center in the middle distance, looking down a row of dishes stretching to a vanishing point deftly hidden by a light rail transit vehicle reminiscent of San Francisco’s BART (this facility is so large that it needs its own trains). This is all under one of Guidice’s trademark dramatic, painterly skies. For the 1975 study on space settlements, Guidice’s images focus on space-based architecture and landscape in a way that displays his experience designing both here on Earth. Guidice was skilled at bringing the novelty back to ground, even if that ground was, in the end, artificial and constructed.

Another study led by Gerard O’Neill, Space Resources and Space Settlements, fleshed out ideas about mining the Moon and the asteroids, features that had been in the background of the 1975 work that focused on the more photogenic habitats. Here, Guidice made the everyday processes of living and working on the Moon compelling to think about. Guidice takes a rectangle on an engineering diagram, labeled “living quarters,” and does a full interior design job on it, showing potted plants, a desk strewn with papers, and a daybed next to a tapestry that would not be out of place on Star Trek: The Next Generation (he confesses to having been a big fan of the original series).17

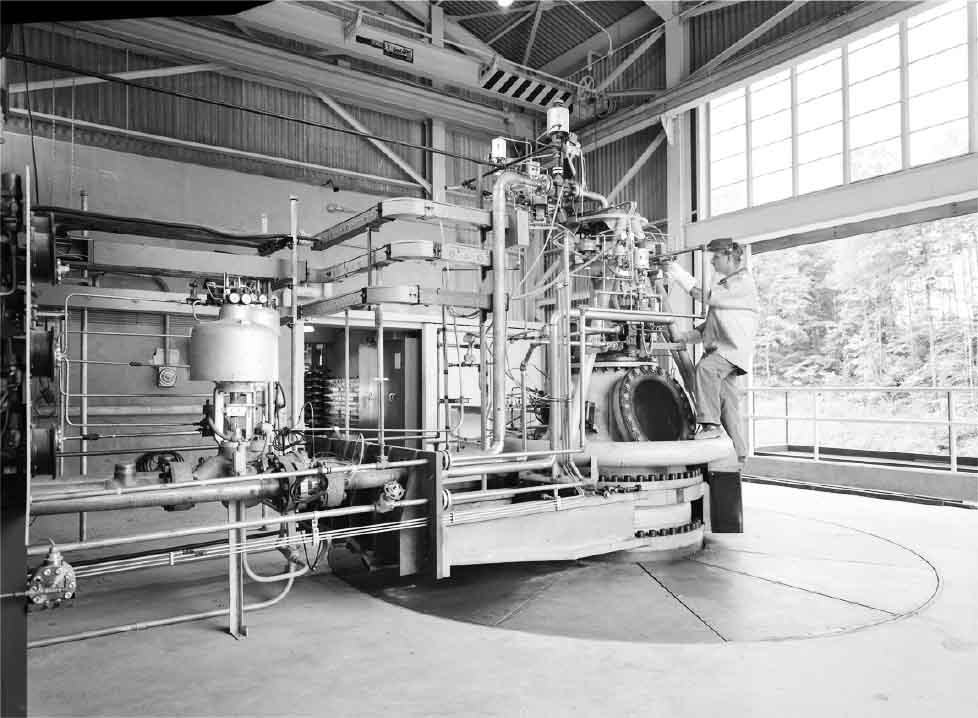

He also paints a control center for the lunar base, and a fully realized, full-scale version of O’Neill’s tabletop mass driver that is sending ore from the Moon out to the space settlement construction site at the L5 Lagrange point, where the gravitational fields of Earth and Moon make a stable place in the endless flux of outer space. The process of launching a ship from Earth orbit out to the asteroid belt, to retrieve a massive floating rock and bring it back home, is turned, under Guidice’s brushes, from cold numbers and telemetry into an image sequence that could be a storyboard for an adventure film.

A 1980 Summer Study called Advanced Automation for Space Missions, on the potential for self-reproducing machines and artificial intelligence, likely influenced O’Neill’s own work on this topic in 2081 and elsewhere. In the montage Guidice painted for it, the Moon is in the foreground, showing an automated factory spreading autonomously across the surface of the planetoid’s surface. A fleet of satellites monitors the Earth’s surface, a Space Shuttle orbiter is docked at a station, and Jupiter and Saturn hover to the upper right, with their own robotic visitors.

And in the middle, as if to emphasize that a human presence is still influential in all of this automation, is a circle made from control panels and monitoring stations, staffed by a man and a woman who look like they are playing an elaborate, immersive video game—fitting, since this is the graphic style that Guidice would later adapt for a series of covers to game cartridges for the Atari console. One detail adds an additional wrinkle: the woman has an elaborate prosthetic robotic arm, like Luke Skywalker in The Empire Strikes Back. In the 1980 illustration, the fusion between human and machine has already entered its next phase.

Guidice’s paintings take these opaque and inaccessible exercises in engineering systems design and make them vivid and arresting. They feed off of the visual culture of science fiction and transform it, and science fiction in turn processes these scenarios a second time, by way of future studies and other secondary sources, according to a cycle of proposal, development, critique, and counterproposal. Arthur C. Clarke’s Imperial Earth illustrates this cycle: Project Cyclops plays a central role, at the small scale as a potential murder scene, and at the large scale as the ancestor for a more advanced SETI system that creates an outside context problem at the book’s closing.

The NASA Ames Summer Studies are the point where different design and future-oriented cultures come together to send signals out to the void, hopefully to be received by audiences in their own cultural radio telescopes. Despite the differences in their backgrounds and demographics, the role of Guidice’s art has striking parallels to that of artist and would-be astronaut Ed Dwight. Both artists produce artifacts that signal to different audiences, but they also both code-switch, sending multiple messages and impressions at once. And as those many constituencies pick up the signals, they start to again recognize each other and connect across the distance between, closing the seams that divide them.

The Launch Will Be Televised

As the 1970s turned into the 1980s, NASA seemed to have a new road map, and the trip looked like it was already underway. They expected that the reusable Space Transportation System, aka the Space Shuttle program, would quickly bring down launch costs. It would, space exploration enthusiasts hoped, demonstrate the feasibility of construction in space as it ferried modules up to build a space station. The shuttle was meant to be the kind of flying pickup truck imagined by Wernher von Braun, taking supplies to a job site in low Earth orbit. This was the next step in the von Braun paradigm—to be followed by travel to Mars.

Meanwhile, the Apollo program was meant to lead to next-generation Lunar hardware, and, in the O’Neill paradigm, evolve into a permanent industrial presence like that illustrated by Guidice—self-replicating semi-autonomous, and supplying raw material for the construction of the O’Neill settlements. The first of these would house a few dozen, the next a few hundred, and then eventually thousands and millions of people would be living in space permanently. These “space natives” would be making various things, including new habitats, but also massive solar powered satellites, soaking up rays in orbit from a sun that never sets.

Project Cyclops, Gerard O’Neill believed, would not be the only thing getting signals in the desert. Acres and acres of microwave receivers would be waiting to convert power beamed from space into usable electricity on Earth. This new power supply infrastructure would, as O’Neill suggested to Congress in 1975, “put the Middle East out of business.”18 Not only oil extraction, but eventually all messy industries, would be moved off of Earth, opening the way for a prosperous, clean, Usborne future, with domed cities and vacuum tube maglev trains allowing anyone to go anywhere to visit or to stay, as long as the computers were tracking.

If the Summer Studies, especially those illustrated by Rick Guidice, were an endorsement of the Usborne future on the part of NASA, they were also a deliberate act of signaling to people like the satellite mission designer who had approached Guidice during my interview at Ames: “We are the kinds of people who want to do things like this, and we are the kinds of people who can do things like this. If you are also the former, join us and we will make you into the latter. Come and help us make sure that things continue to go up and to the right.”

This was the message going out to the Baby Boom generation, including an upwardly mobile, predominantly white middle class that was now finishing college and moving into economic and political life. But there were others who were excluded from access to that agency and life. Black Americans, in particular, were reading a very different message in the signals broadcast by NASA.

In 1970, poet and recording artist Gil Scott-Heron released Small Talk at 125th and Lenox. The album title situates us in a place—the heart of Harlem, on a street that is now renamed Malcolm X Boulevard. And this is a place that is not mediated, figured, signaled, or broadcast in any ordinary way. As we learn in the first track, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” unlike the Apollo landings, which showed the world conclusively and credibly, that it was now in the era of “Whitey on the Moon,” the title of track nine.19 This recording makes a direct connection between poverty on Earth—Black poverty specifically—and expenditures on space exploration. And Scott-Heron goes further than that, linking the rising cost of food, health care, and housing to the Moon landings. The inhabitation of space is seen by Scott-Heron as a kind of gentrification: when white, affluent people go to new places, he points out, prices tend to rise.

Scott-Heron’s record came out after the first Apollo Moon landings, but even before Apollo 11, other activists and critics were making this same kind of connection between spending in outer space and economic hardship on Earth. Reverend Ralph Abernathy was a cofounder of the Southern Christian Leadership Council, the civil rights organization that was led by Martin Luther King Jr. Abernathy became that organization’s president after King was assassinated in 1968, the same year that Apollo 8 made its historic first flight around the Moon. Abernathy also took over the leadership of the SCLC’s latest activist project, the Poor People’s Campaign. Seeking to change the conversation on inequality once again, the goals of the Poor People’s Campaign were to unite those suffering from poverty across racial and ethnic lines. They took as a starting point the premise that the goals of poor people, whether white, Black, Hispanic, Asian, or Native American, converged on far more points than they differed.

This was an attempt to create new relationships between the parts and the wholes in American life. In the summer of 1968, they set up a large camp with thousands of residents on the National Mall, demanding that the US government implement an Economic Bill of Rights that would have five guarantees: jobs at living wages, backup minimum income, access to land, investment funding, and a greater role in governance. Their demands were ignored, and the camp was evicted the day after their permit ran out. The next year, Abernathy turned the attention of the Poor People’s Campaign toward the space program, and marched on NASA.

On the day before the Apollo 11 Moon launch, July 15, 1969, Abernathy and marchers from the Poor People’s Campaign, along with several donkeys pulling carts, stepped up to the gates of Cape Canaveral (then known as Cape Kennedy). They were here to draw attention to disparities in funding between space exploration and social programs. “We may go on from this day to Mars and to Jupiter and even to the heavens beyond,” Abernathy told the gathering crowd and press, “but as long as racism, poverty and hunger and war prevail on the Earth, we as a civilized nation have failed.”20 NASA administrator Tom Paine came out to meet them, replying to Abernathy, “If we could solve the problems of poverty by not pushing the button to launch men to the Moon tomorrow, then we would not push that button.” The Apollo program cost somewhere between $152 billion and $250 billion, total, in 2020 dollars, depending on how the research, testing, and other indirect spending is counted.21

In the same year that the SCLC occupied the National Mall, Congress passed the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968, a record-setting expenditure on American housing that authorized $13 billion in spending during the first year alone. That budget also gave almost $35 billion to NASA—down from a peak of nearly $47 billion in 1966, when NASA consumed about 4 percent of all federal money for the year. Nevertheless, Paine later recalled telling Abernathy “that the great technological advances of NASA were child’s play compared to the tremendously difficult human problems with which he and his people were concerned.” And besides that, he went on to ask Abernathy to think of the meaning behind the highly visible gesture about to take place: “I said that he should regard the space program … as an encouraging demonstration of what the American people could accomplish when they had vision, leadership and adequate resources of competent people and money to overcome obstacles.” Paine also remembered asking Abernathy to “hitch his wagons to our rocket, using the space program as a spur to the nation to tackle problems boldly in other areas, and using NASA’s space successes as a yardstick by which progress in other areas should be measured.” Paine saw Abernathy’s march and rally as a request that the kind of “science and engineering” that NASA was doing be used to help with social and economic issues, and he promised to try to make that happen.

This tension between science and society was also a factor in Gerard O’Neill’s decision to ask his students about ways to use engineering and physics to tackle social issues by building new worlds. And while Abernathy and Paine were having their conversation at the gates of Cape Kennedy, another ex– NASA administrator was working on exactly the kind of technology transfer that they were discussing.

The HUD act of 1968 had made possible new programs that looked for opportunities to apply the technical and logistical expertise from places like NASA to the construction of rapidly built, mass produced, affordable prefab housing in the United States. HUD hired Harold Finger, the former head of a NASA research program on nuclear propulsion, to run Operation Breakthrough. By 1976, however, the program had already been declared a failure. Paine’s insistence that technology was child’s play compared to the issues that Abernathy wanted to tackle was prescient. The General Accounting Office report on Breakthrough’s failure cites five top-level bullet-pointed reasons:

—fragmented governmental jurisdictions that prevent formation of the large markets often necessary to take advantage of modern technology,

—the inability of State and local governments to support or undertake experimentation needed to develop new or improved technology,

—resistance to change by parties with vested interests,

—private industry’s reluctance to invest in technology not yet proven to be feasible and practical, and

—Government policies that inhibit technology use.22

As is visible in the budget lines, hard technology is not so much the obstacle; instead, it is the incentivization and prior-itization of technology’s development and application to specific uses that creates sticking points. Housing, one of Le Guin’s “soft” technologies, is simply not an exciting enough goal to justify overcoming the kinds of obstacles that NASA had overcome while working toward their moonshot.

At the close of their conversation, Paine invited Abernathy and some of his fellow marchers to attend the launch in the VIP section the next day, and after the launch, he recognized the impact of this occasion. “For that particular moment and second,” Reverend Abernathy remembered, “I really forgot that we have so many hungry people in the United States of America.”

The Space Shuttle program, at a cost of around $249 billion over thirty years, did not live up to expectations for very long, either. The initial intent was to create a fully reusable pickup truck to haul supplies and people to space, but in practice, only the orbiters were totally reusable, and those had lifetime issues that showed up later, with deadly consequences. The two Shuttle orbiters that failed—resulting in the deaths of their crews—Challenger and Columbia—were also the oldest in the fleet still flying at the time. Launch, as it turned out, was more costly and dangerous than many people had anticipated.

Moreover, the Shuttle had too many potential audiences and too many potential user bases to satisfy everyone. Where NASA saw a space truck capable of building a space station where the utopian influence of the overview effect might be possible, the military saw a potential hauler and launcher of surveillance satellites watching from the sky. To this end, the Shuttle orbiter’s wing profile was modified such that it could potentially be used to conduct missions involving the capture of Soviet satellites. The Air Force wanted it to have the capability to land quickly, after a short and stealthy top secret flight, at Vandenberg Air Force Base. These faulty attempts to code-switch, unite audiences, and send multiple signals only added expense and reduced capacity.

Other early compromises in the Shuttle’s design process traded lower initial costs in construction and development for a lifetime cost that was higher than more reusable systems would have allowed. The two solid rocket boosters were only partially recoverable, and the large external tanks were discarded after each flight. In the same kind of situation that took down Operation Breakthrough, compromises and breakdowns in the composition of constituent audiences left the idea of modularity and reusability behind.

These were not the only setbacks to NASA’s brief alliance with the Usborne future via Gerard O’Neill and his followers. Still, it was fun while it lasted, and O’Neill’s ideas were enjoying a peak in interest and publicity during the late 1970s. His regular newsletter to fans and adherents had spun off into L5 News in 1975, run by a group of interested proponents called the L5 Society. The first official issue of this new publication included a note of support from Congressman Morris Udall, who had been a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination the previous year.

Psychologist and pyschedelics evangelist Timothy Leary was a fan as well. Leary incorporated O’Neill’s space settlement ideas into his own quasi-cosmist “SMI2LE” framework for the future of humanity: Space Migration, Intelligence Increase, Life Extension. Before encountering O’Neill’s work, Leary had already taken an interest in some of these notions. While in prison in 1973, Leary wrote a pamphlet, The Starseed Transmissions, about how the comet Kohoutek, then falling toward the inner Solar System, might represent a signal from extraterrestrials. Who needs Project Cyclops to hear from aliens, when you have the time and space in jail to meditate and listen? The pamphlet ends with his disappointment on learning that the third crew of the space station Skylab were to study the comet and reduce its inherent sense of wonder to the object of scientific analysis. “NASA beat you to the media,” his friend commiserates. “They’ll try to co-opt the comet.”

These strange alliances did not last long; indeed it seems O’Neill was never comfortable with Leary’s attention or advocacy.23 Meanwhile, other forces in Congress were trying to co-opt NASA. In October 1977, O’Neill’s space settlement scheme probably hit a high-water mark when it was the subject of a segment on the prime-time public interest show 60 Minutes. The following week, the hosts read a letter on the show from Democratic senator William Proxmire that said, in part, that space settlement was “the best argument yet for chopping NASA’s funding to the bone. As Chairman of the Senate Subcommittee responsible for NASA’s appropriations, I say not a penny for this nutty fantasy.”

Proxmire succeeded in his efforts to cancel the American program to build their own version of the European super-sonic Concorde commercial jet, a concept right out of the Usborne future via NASA Ames. Proxmire also effectively killed any aspiration to build Project Cyclops when he introduced language in an appropriations bill that explicitly prohibited NASA from spending money to listen for extraterrestrials. In 1975, the NASA Ames space settlements Summer Study, led by O’Neill, estimated the total cost for the construction of a complete base model habitat for 10,000 people, a giant bicycle wheel, a mile across, spinning at 1 rpm at the L5 point. Their planned design, the Stanford torus, would break the bank at around $1 trillion.24

As of this writing, at the end of 2020, NASA’s budget is down far past its peak in the Apollo era. In 2020, NASA received only $22.6 billion, not even 0.5 percent of the $4.7 trillion in total federal spending for the year. Today the term “proxmired” is still used in institutional cultures to describe the deliberate targeting of programs or initiatives for performative political reasons.

F for Fake

The architectural historian Eduard Sekler was one of the first people to try to codify the meaning of the term “tectonics” in architecture. As discussed in chapter 1, tectonics is about the relationships of parts to other parts, and parts to wholes. For Sekler, it is in the space that opens up between the actual reality of the way the pieces go together (which Sekler calls “construction”) and the abstract idea about how they go together (“structure”). Tectonics is the visible expression that mediates between these two.25

Another historian, Kenneth Frampton, goes further, and points out that this opportunity for expression opens up all kinds of other, almost literary, capabilities, which he calls “poetics.”26 Where there is poetry, as Plato tells us, there are lies. Alexander MacDonald, again, in The Long Space Age, links the idea that the Cold War space race was about “prestige” to other layers of meaning that the word carries. “Prestige” is also used to indicate the showy performative flourish in a stage magic show, which all at once is both a demonstration of a capability that seems impossible, a mystery of the third kind, and an establishment of a kind of credibility on which that the rest of the show depends. As Nicholas de Monchaux points out, the Apollo 11 Moon landing—designed as it was to produce a specific image—is just such a performance.

In President Richard Nixon’s phone call to Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, answered by the two astronauts from the surface of the Moon, he was explicit about the kind of planetary imagination that this performance was designed to produce. “For one priceless moment in the whole history of man,” Nixon said, about Armstrong’s first steps on the Moon, as televised globally, “all the people on this Earth are truly one.” Nixon was trying to express an abstract concept, about how the parts of the human population on the planet can come together, but it was belied by built reality, as Reverend Abernathy would point out, after his own sense of wonder invoked by the launch of Apollo 11 wore off.

The Apollo program had barely ended before some prominent voices started calling the whole thing a fake. The first, and later the most famous, proponent of the conspiracy theory surrounding the Apollo Moon landings was a man named Bill Kaysing. Kaysing had worked as a technical writer in the early 1960s at Rocketdyne, the company that made the powerful F-1 engines in the first stage of von Braun’s Saturn V rockets. Even though he had not worked there since 1963, six years before Apollo 11, he relied on that fact to lend credibility to his claims in a book that he self-published in 1976, bluntly titled We Never Went to the Moon: America’s Thirty Billion Dollar Swindle.

Since the Apollo program was so expensive, he claimed, and the importance of obtaining an image of an American on the Moon was so great, he said, when NASA found out that the trip was impossible, they simply kept the money and faked the pictures. In a perfect irony, Kaysing’s case relied on those same images. As evidence, he points to the fact that there are no stars in the Moon’s sky, when in reality this was an effect of the short exposure times used to capture the bright regolith that makes up the surface, which is lit by unfiltered sunlight. The shadows were all wrong, he claimed, pointing to areas that he did not realize were sloped. There should be a blast crater where the descent module landed, he pointed out, without knowing that the engine’s exhaust quickly spread out under the craft, scattering debris over a wide area, as is visible in landing footage.

These false claims, which started with Kaysing’s book and never really died down, are absurd, but understandable. NASA is a producer of systems and a producer of images, acting in science fiction one moment, and producing scientific facts in another. They work in the space between facts and fiction, and all of their image-making activities involve both mediation and manipulation. The effects in the film photographs made during Apollo were not quite capable of capturing the visual qualities of the lunar regolith and landscape, says Apollo astronaut Alan Bean, who, like Alexei Leonov and Ed Dwight, was also an artist. Bean’s paintings of the lunar surface have a more complex set of warm and cool tones than the monochrome grey that shows up in the color film shots. As Buzz Aldrin called it, this “magnificent desolation” was richer and more intricate than photos could reproduce.

And even those photos themselves captured enough ambiguity that they could be interpreted in different ways, as Kaysing’s book, stripped of its paranoid overtones, rightly points out. Like Dwight’s sculptures of civil rights struggles, they were interpreted by different audiences in different ways. Not everyone got to go and see these views for themselves. Kaysing, a working-class technical writer with a degree in English, was certainly not going anytime soon, though he played a role in the system that eventually sent Bean and enabled the production of his paintings.

In the 1960s, after leaving Rocketdyne, Kaysing estranged himself from his family and lived out of his car for several years. His first book, before he began writing about hoaxes and conspiracies supposedly perpetrated by NASA, was The Ex-Urbanite’s Complete and Illustrated Easy-Does-It First-Time Farmer’s Guide. Published in 1971, it could have sat on bookstore shelves alongside Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog, which itself had a picture on its cover of Earth, taken by the ATS-3 weather satellite. This was a nod to Brand’s famous 1966 challenge to NASA in a public campaign, in which he asked, “Why haven’t we seen a photograph of the whole earth yet?”27

Kaysing, and his ongoing legacy, are an unfortunate artifact of the post-Apollo period of disillusionment with NASA. The alliance that Usborne and The Kids’ Whole Future Catalog promised—between DIY countercultures looking for more freedom, and Big Science researchers funded by Big Government—had broken down. So too did NASA’s potential adoption of the O’Neill paradigm, tantalizingly real in Rick Guidice’s paintings for the Ames Summer Studies, get proxmired into oblivion during the late ’70s and into the ’80s.

Kaysing’s cynicism is, in several ways, of a piece with the disappointment felt by Timothy Leary, the L5 Society, and millions of potential space cadets who were hoping to help build a future that featured multi-racial cocktail parties in the Bernal sphere and levitating vacuum tube trains to domed cities in Antarctica. There’s a phrase that became popular during this period, among conspiracy theorists and true believers alike: “NASA: Never a Straight Answer.”

But even those who do get to go to space will have their perceptions mediated by NASA, its engineering hardware, and its social soft power. Alongside “artist’s impression,” another disclaimer commonly used to manage expectations about the gap between image and reality is “false color.” Images of nebula far away, or the closer, but still improbably distant, surfaces of other planets and moons, are always constructed artifacts. We may be seeing colors that represent wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum that no human visual sense could perceive, captured by instruments like those imagined by J.D. Bernal, designed not to produce a satisfying picturesque landscape photo, but to conduct scientific research. The telescopes on Skylab reduced Leary’s magical alien comet messenger to a mere ball of ice and rock.28

In space, a completely hostile environment, it is impossible to view things with anything like a “naked eye”; that eye will always be behind a visor or viewscreen or porthole. Wherever you go, you’re not really there. It’s not hard to admit that NASA has achieved breakthrough after breakthrough in its sixty-plus-year history. And NASA is very open about its technical failures, when they happen. The tragedies of the 1967 Apollo 1 fire, which killed three astronauts, and the shuttle disasters with Challenger and Columbia, which killed a combined total of fourteen, are all, for Kaysing, just part of the cover-up and conspiracy. But in reality, they were investigated in full public view, for the most part, and they were used themselves as scientific experiments, producing more facts that would prevent future failures. The social and political breakdowns, though, are protected by an internal culture that values flight above all. And even astronauts who seem to have been passed over for mysterious, unspoken reasons, bumped from flight like Jeanette Epps and Yvonne Cagle, will never get a public hearing on their case.

Jesse Strickland, as he drove across the Midwest to give yet another public lecture, was retired from NASA; he no longer had any professional obligation to share the image he had cherished, along with O’Neill and so many others, of an enduring human future in space. He was doing it because he wanted to. Having been both a hidden and visible figure, Strickland was under few illusions about the way race and space were mediated in America. Working at NASA for thirty-three years, he surely knew what a “false color” image was. And his lifelong experience as an architect left him no stranger to ideas about tectonics.

Like his fellow architect Rick Guidice, he knew well the persuasive power of the artist’s impression. He also knew the utility of working at different scales, and the necessity of working with many trades, on the long-term construction of spaces and worlds. For Strickland, projects like the job program he coordinated with adult returning high school students were of a piece with his work advocating for the eventual construction of large-scale space habitats, and the fulfillment of something like the O’Neill paradigm that would lead to millions of people living and working there. And he knew how to get multiple constituencies engaged in that time-line. “I don’t use a podium or microphone if I can help it,” he told one local newspaper, “I like to interact with my audience and give them a chance to get involved and do some exploring on their own.”29

There is a painting that Guidice made for a SETI proposal at NASA Ames, showing the construction of a large-scale radio telescope in space, a generation beyond Project Cyclops, which would have a single “ear” over half a mile wide. It was repurposed to illustrate the Space Settlement Summer Study publication a few years later. Characteristically, it shows the complexity of systems in a compelling and legible way. In this rendering, he uses the relative scale of human figures and Space Shuttle–esque spaceplanes to show the size of the construction, and the scope of the ambition involved. He sets up this revelation with a figure in the foreground, a spacesuited human holding some kind of complicated wrench.

Rick Guidice admitted, in a 2015 interview, that he had made up the tool: it was simply meant to look mysterious and futuristic.30 But the image resonates with something that his fellow designer Jesse Strickland said, to a former student, as recalled in a recent conversation. A lot of things and a lot of different kinds of people would be needed for this long-term future in space, including, he said, people who can handle a wrench.