We all have our dark little secrets – those sources of shame which make us flinch whenever they come to mind. So it is with every town and city. And none more so than the city of London, which has enough skeletons in its cupboards to keep the whole place a-rattling from now till Kingdom Come.

One of its guiltiest secrets is that, for a good proportion of the nineteenth century, bears were kept locked in its sewers, where they served as the city’s unpaid flushers and toshers. Around a hundred bears patrolled that stinking labyrinth of pipe and tunnel which carried away the waste from the city’s homes and factories, and drained the water from the streets. Without their efforts every heavy rainfall would have plunged the whole place underwater and the air would have been thick with pestilence.

But make no mistake, the bears were prisoners. Every grate and manhole cover was locked tight-shut. The only light that found its way down to them was that which filtered through the grates and gulleys, or came up from the gates where the drains emptied straight into the Thames.

It was the bears’ unenviable task to accompany the city’s effluvia, from the moment it first entered the system right down to the river. True, gravity bore some of that burden. But it is in the nature of sewage to coalesce at every opportunity, to silt-up at every turn. The bears’ only objective was to keep things moving. For they knew that, whatever they managed to clear before them, there would always be plenty more coming along behind.

Bears were regularly carried away in the throes of a flash-flood. To try and guard against such an eventuality they constructed a series of ledges – shadowy recesses high up in the brickwork, to which they could retreat whenever the levels suddenly rose. Even so, every hour of labour was carried out in fearful anticipation of a downpour. If the drains were not sufficiently clear they knew the sewage would rise – and keep on rising – and no matter where the bears were hiding the flood would eventually find them out.

All in all, it was a sorry sort of existence. Their only nourishment came from whatever edible scraps they happened to find about them, or acquired by trading those few items of value they turned up during the day. The sewers beneath the breweries and slaughter-houses were significant stations on their circuits, but were just as popular with every other creature trying to survive underground. On the whole, rats were more wary of bears than vice-versa, and, if necessary, the bears were quite prepared to make a meal of them. But the rats were quick, and capable of delivering a nasty nip before departing so, by and large, bear and rat left each other to their own individual brand of misery – or as much as was possible in the circumstances.

The bears operated in gangs, each team despatched to a particular precinct, with their makeshift rods and shovels to prise the foul matter from where it had set. They worked in shifts, moving in as soon as possible after someone had shot the night soil or deposited a tank or two of offal, whatever time of night or day that might happen to be.

A century later, long after the bears had abandoned the tunnels, a group of academics, investigating the bears’ subterranean existence, discovered great expanses of wall, decorated with a multitude of tiny scratches, which they interpreted, quite wrongly, as bear-hieroglyphics … something akin to the primitive cave drawings in France and southern Spain. But there was nothing remotely artistic about them. They were simply a means for the bears to mark off those parts of the city which had been visited and the distribution of bear-labour on any given day.

The concentration of so many pestilential and poisonous gases meant there was always a risk of explosion and, from time to time, some errant spark would set the whole lot off. The authorities took a philosophical view on the matter, being of the opinion that, as long as such explosions were kept below ground and didn’t injure anybody of import, then they were to be tolerated. So it wasn’t unusual for Londoners to hear a muted thump and register a minor tremor through their shoe leather as some hideous combination of gases, long compressed between the brickwork, finally found the ignition it craved.

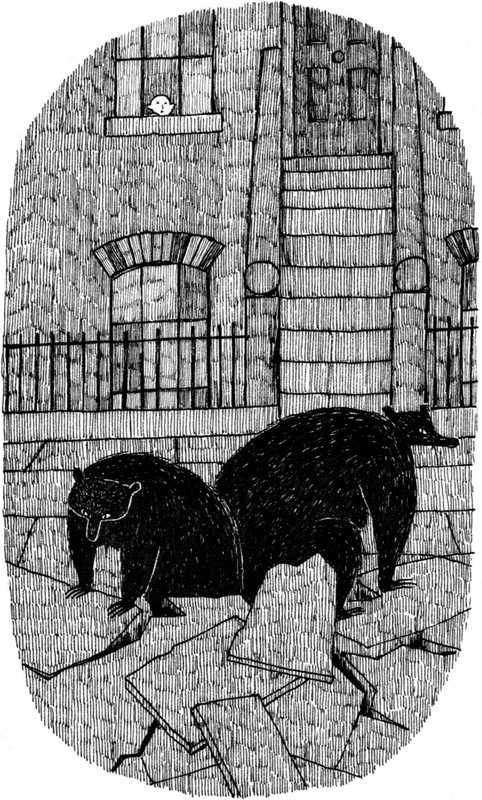

In the summer of 1849 the pavements of John Street, just off Gray’s Inn Road, unexpectedly erupted and, soon after, two bears were seen climbing out between the flags. They got as far as Red Lion Park where they climbed up into the trees. Marksmen were brought in and both bears were shot and killed. Their bodies were taken away and disposed of, and those passers-by who happened to witness the incident were encouraged to keep it to themselves.

The bears lived in constant fear of such explosions and did everything in their power to prevent them coming about, but they also knew that such an event offered their only chance of freedom, so whenever a sewer did go up they would rush to the scene, partly to see if any bear had been injured, but also carrying with them some faint hope that their moment of liberation might have finally arrived.

The odd explosion, along with the general wear and tear of the tunnels, necessitated a certain degree of maintenance beyond the bears’ abilities, and the men who undertook these brief ventures into the underworld did so with the same level of wariness as a sortie behind enemy lines. Among those employed to do such work, stories were rife of men who’d failed to watch their backs and been dragged off into the darkness.

‘They loves human flesh,’ one fellow was fond of saying. ‘To bears, we tastes just like chicken.’ Although how he happened to come by such particular information was never made clear.

It is impossible to estimate what number of Londoners knew of the bears’ existence. Certainly, no committees were formed to lobby for an improvement in their conditions, and no Member of Parliament got to his feet to call for their release. The best that can be said is that it was a subject on which most people chose not to dwell.

The only Londoners to have regular contact with the bears were the Gutter Traders, an informal association of no more than twenty men in all. As already stated, the bears would gather on their rounds a certain amount of edible matter (if that is not too exaggerated a claim for it) as well as any odds and ends which might have some value to those citizens up above. The simple fact is that the bears lived their lives in a state of perpetual hunger. In order to avoid starvation they developed a means of exchanging any knick-knack they had found or the odd coin or piece of jewellery for some morsel of food which might help sustain them and their fellow-bears through another day.

At dawn, it was not unusual to find some seedy-looking character kneeling at the kerbside, apparently conversing with a drain. Every now and again they would slip their fingers through the grate and pick something out. Then bring it up to their face and examine it, sometimes with the aid of an eyeglass. There would follow a period of negotiation. Finally, some package of meat or bag of left-overs would be deposited. Then the dealer would take up his latest acquisitions and go on his way.

The system was far from perfect, but worked well enough for both parties to persist with it. Any Trader who drove too hard a bargain would find themselves avoided. If the bears were too demanding they would go without.

In such negotiations the Trader did all the talking. If the deal was considered unacceptable, the bear would shake its head. Then it was up to the Trader to restate his position, or amend his terms. Some deal was usually struck. And, to be fair, it was a rare day when there was anything like outright hostility, which was due in no small part to the fate suffered by a local character known as Jimmy the Hat.

Jimmy got his name on account of his rather beaten old bowler that he was said to have picked out of the gutter. He’d been dealing with the bears for no more than a fortnight and was there early one morning, at the usual grate. A couple of bits and pieces were passed up: bent cutlery, some sort of buckle and so on, none of which had made much impression.

‘Anythin’ else?’ said Jimmy.

The bear studied Jimmy for a second, apparently uncertain as to whether to proceed. Then slowly unfolded a grubby old rag. A gold ring sat in it. Jimmy could see it glinting just below the bars and he knew, even at that distance, that it was worth something. He could feel it in his bones.

The ring had a stone set in it, which caught a small fraction of light. ‘Pass it up,’ he said.

The bear was reluctant to hand the ring over – had spent enough years sifting through the filth and trading the few things that were to be salvaged from it to appreciate that this was not your average find.

Jimmy the Hat was all shrugs and open palms. ‘I’ve got to have a proper look,’ he said, ‘to see if there’s any maker’s marks on it.’

The bear didn’t have much choice, and eventually the ring went up through the bars, just as it must have once slipped down between them, except this time it was held between the claws of a bear. Jimmy took it and brought it up to his eye. And even as he did so, he was already getting to his feet and glancing over his shoulder, as if to find the light. When he was standing he had one more look at the ring, then calmly slipped it in his waistcoat pocket. Then he winked at the bear beneath the bars, turned, and walked away.

The bear let out a great roar from its dungeon, but Jimmy was already scuttling off down the street. The bear roared again and pressed its nose right up against the cold metal, to try and get one last sniff of Jimmy – to draw in the man’s rancid smell and hold it there.

There was nothing to be done. The other bears were informed of the situation and told to keep an eye out for the evil little shyster. And for the next few months the cheated bear went out of its way to work in those neighbourhoods that a swindler such as Jimmy the Hat might frequent.

The weeks went by. One Trader said he’d heard how much Jimmy had sold the ring for – enough to feed the bears for well over a month. Another said he had it on good authority that Jimmy had upped sticks and headed west. The other bears turned their attention back to their clearing and shovelling, but at night the cheated bear would lie on its ledge and relive every dreadful second until its whole body burned and ached.

Then one day, quite out of the blue, Jimmy was spotted over in Whitechapel, outside the old Cock and Bottle, having had an ale or two too many and been thrown out for causing a scene. The bear he’d robbed was informed and was over there in a matter of minutes. Managed to clamber up a drain and get its snout right up to street level.

The bear drew in a deep draught of the East End evening. And in among the hundred other smells, it could clearly pick out that thieving beggar, Jimmy the Hat. The bear pulled back its head, twisted itself round and got a shoulder right up into the culvert. It could hear Jimmy now, sounding off to a taxi driver, and a few moments later insulting a woman who happened to be walking by.

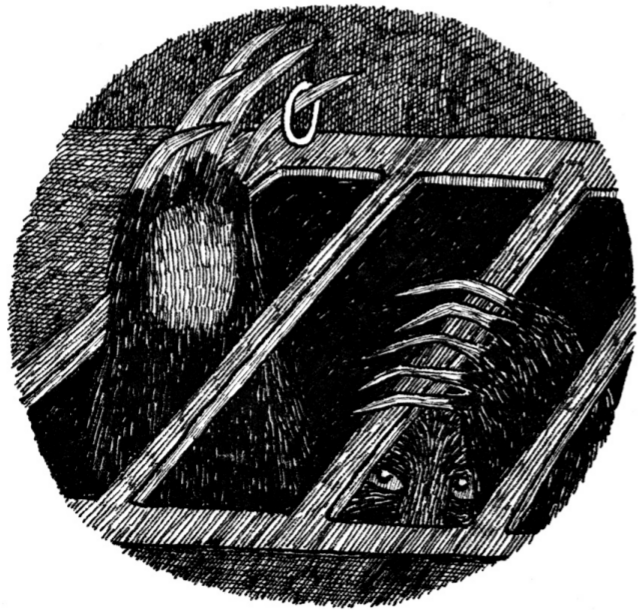

A boot stepped down into the gutter and was soon joined by its twin. The feet shuffled as they did their best to keep their owner upright. Jimmy was about to head off across the road, but at the last second was obliged to stop as some carriage went flying past him. The bear heard Jimmy curse the driver. Then it reached out and made a grab for him.

The carriage was gone. Jimmy had finished his shouting. He set off. But something was stopping him – something interfered. He thought perhaps he’d got his boot caught up on something, but when he looked down he saw a great paw clamped round his ankle. Jimmy had drunk many beers and several whiskies, but in that instant he became as sober as a judge.

He tried to tug his leg away, but it wasn’t moving. He tried to kick at the paw with his other foot but the bear didn’t mind a bit. Jimmy dropped down into the gutter and tried undoing his laces. It would be worth the loss of a boot, he thought. But every time he went anywhere near the laces the bear just shifted its grip, until it had a hold of his shin instead.

Jimmy began calling out to passers-by to help him – the same passers-by he’d been abusing only minutes before. Most of them just ignored him. The rest took one look at the situation and decided not to get involved.

With every minute, Jimmy was getting more and more frantic. Below, the bear could smell the bitter panic in his sweat. The other bears gathered round and offered to help – to try and get a hold of the other boot, or to take over for a minute – but all offers were refused. There was only one possible set of circumstances in which the bear would ever consider releasing its grip.

After half an hour or so, Jimmy collapsed, through sheer nervous exhaustion. This was probably not advisable. For one thing, it allowed the bear to drag his foot deeper into the culvert. For another, it allowed the bear to get a good look at him. Jimmy saw the bear’s eye glinting in the darkness. The bear saw the same eye that had winked at him before making off with that precious ring.

It isn’t true that Jimmy was eaten alive. It is one of those little legends which seem to gain credence with the passing of time. The fact is that once the bear got enough of Jimmy’s leg down into the gutter, it took a bite or two – just to get him bleeding. After that, the bear was quite happy to hold on and let all the life slowly drain out of him.

For the last hour of his life Jimmy had quite an audience – they stood on the other side of the street, not saying a word. Just watching, as Jimmy went through one or two periods in which he made quite a fuss and squealed and thrashed about like a trapped animal. Then periods when he grew quite still.

When he was finally dead the bears dragged the body down into the sewers with them. Bears are practical creatures and will make use of whatever meat happens to be lying around, which is probably where the stories of Jimmy being eaten alive have their origins. He went down bit by bit, until with one last tug Jimmy’s head disappeared into the darkness and all that remained in the gutter was his battered bowler, less than quarter of a mile from where he’d first picked it up.

*

For the bears, Jimmy’s comeuppance was a significant victory, but all too soon the daily grind reimposed itself, and the idea of Jimmy held by his ankle began to recede. And it was back to the old routine of trudge and sludge, with just an occasional breather. Then sleep, high up among the brickwork, as if the bears were a part of the city’s very soil.

At each day’s end the bears would gather by the main gate, where the passage widened before disgorging its contents into the river. Twenty or thirty bears would sometimes sit and stare out over the water, watching the barges. Or gaze up at the stars as they sailed overhead.

In winter it would sometimes get so cold that chunks of ice formed in the river and one February the Thames froze solid from bank to bank. The warmth of the sewage formed a small pool right by the outlet, but beyond it the only navigation on the water was by foot or skate.

That weekend there was a Frost Fair, with dozens of different rides and stalls, and it seemed the whole city was marching up and down and drinking beer and falling over, as if the Thames was just any other thoroughfare.

The bears sat and watched from the shadows, until it was time to take up their hoes and shovels and return to work. But on the Saturday afternoon a young child spotted some movement up the tunnel. He’d taken twenty steps and stopped at the ice’s edge before his mother missed him. She turned and went scurrying after him.

‘Did you see them?’ the child asked his mother as she led him back towards the bright lights. ‘Did you see the bears?’

*

Three months later a dozen or so bears sat on that same ledge, looking out at the water. The river was still and quiet. Some of the bears were already dozing, when a barge slowly swung into view.

Something about the boat’s progress caught the bears’ attention. It lacked the decisive nature of most barges: their blunt determination. In comparison, this barge seemed positively aimless. The fact was that its captain, having worked like a dog for two days solid, and having been up and down the river twice already today, and having just picked up his last load of coal and being on his way back to Limehouse, must have relaxed a little – in fact, relaxed to such a degree that his chin now rested on his chest, his eyes were closed and the wheel was doing nothing but support his hands.

The bears watched as the barge advanced at a sideways angle, then came right at them. They’d seen plenty of barges over the years but none had ever come within twenty yards of them.

It’s bound to turn, they thought. Bound to turn away at any moment. Until, one by one, those moments all ran out and the bears had to allow that the barge’s collision with the gate was a possibility, then a probability, then imminent.

If the barge had been empty it might not have made such an impression, but those forty tons of coal ensured that, even after the initial impact, the barge kept on coming – kept on driving right up the tunnel.

The bars popped out of their footings, the gate went under and was dragged squealing for twenty feet or more. The barge continued – straight up the main drain, until its prow was right among the bears. It paused there for a couple of seconds, as if considering its new surroundings, then slowly withdrew; slipped back into the river and drifted, backwards, towards the opposite bank.

The captain was awake now, along with every bear in the sewers. Those dozing by the main gate had jumped up at the sound of the collision. But throughout the city’s pipes and drains there was a moment when the bears froze and turned in the direction of the commotion. Then they were all heading towards it as fast as they could.

The bears had no way of knowing whether the river they’d looked out at all their lives would support them or take them under. It seemed quite reasonable that they would be able to swim, but it was nothing more than an inkling. So having waded tentatively into the water they were mightily relieved to find that the river actually buoyed them up.

London continued to go about its business, oblivious. It was late, but hundreds of people still went up and down the Embankment and crossed the bridges of Southwark and Blackfriars. There appeared to be some fuss on the south bank of the river, but nobody spotted the great huddle of bears as it drifted within fifty yards of them.

The bears instinctively knew that too much movement would only draw unwanted attention. Besides, the tide was on the ebb and so, just as it supported them, it also drew them east, out of the city. And when the river widened the bears finally felt safe enough to do a little paddling of a more concerted kind.

They came ashore, wet and cold, on Two Tree Island, a few miles short of Southend-on-Sea, and sat on the beach wondering where on earth they were, what direction they should be going and where their next meal might come from.

On securing its release a creature which has long been imprisoned might suffer a moment or two’s profound anxiety – might experience something which could be misconstrued as misgivings, or uncertainty. But it is nothing more than disorientation. And so it was at Two Tree Island. The moment came and went. The bears got to their feet, brushed themselves down and headed north.