WITHIN TWENTY YEARS of the crucifixion, Christianity was transformed from a faith based in rural Galilee, to an urban movement reaching far beyond Palestine. In the beginning it was borne by nameless itinerant preachers and by rank-and-file Christians who shared their faith with relatives and friends. Soon they were joined by ‘professional’ missionaries such as Paul and his associates. Thus, while Jesus’s ministry was limited primarily to the rural areas and the outskirts of towns, the Jesus movement quickly spread to the Greco-Roman cities, especially to those in the eastern, Hellenic end of the empire.

All ambitious missionary movements are, or soon become, urban. If the goal is to “make disciples of all nations,” missionaries need to go where there are many potential converts, which is precisely what Paul did. His missionary journeys took him to major cities such as Antioch, Corinth, and Athens, with only occasional visits to smaller communities such as Iconium and Laodicea. No mention is made of him preaching in the countryside.

Paul was not a special case: it was several centuries before the early church made serious efforts to convert the rural peasantry—although many were converted by friends and kinfolk returning from urban sojourns. Fully sharing the views of their non-Christian neighbors, many early Christians dismissed rural people as subhuman brutes. “The peasantry of the countryside were beyond the pale, a tribe apart, outsiders. Such attitudes underpinned the failure of the urban Christian communities to reach out and spread the gospel in the countryside…. For them the countryside simply did not exist as a zone for missionary enterprise. After all, there was nothing in the New Testament about spreading the Word to the beasts of the field.”1

Any study of how Christians converted the empire is really a study of how they Christianized the cities. Consequently, this chapter is devoted to the Greco-Roman cities. I will begin by examining the nature of cities and of urban life in this era and analyzing the religious situation in the urban empire. I will then identify a specific set of cities on the basis of population size and provide brief sketches of each, as these will be the ‘cases’ on which all of the subsequent hypothesis-testing will be based.

Urban Life

Greco-Roman cities were small, extremely crowded, filthy beyond imagining, disorderly, filled with strangers, and afflicted with frequent catastrophes—fires, plagues, conquests, and earthquakes.

Only two major cities in the empire, Rome and Alexandria, had more than 150,000 inhabitants, and many had fewer than 50,000. But, it wasn’t only lack of population that made these cities ‘small’; they covered very small areas and consequently were extremely dense. Consider Antioch. Having a population of about 100,000, it was two miles long and a mile wide, which yields a result of 78.2 persons per acre. Subtract the 40 percent of the city devoted to streets, temples, and public buildings, and the density of the inhabited area rises to 130 per acre—greater than in modern Calcutta. Even so, Antioch was far below the density of Rome, which was somewhere from 200 to 300 persons per acre!2 To get a sense of this density, imagine yourself living on a popular ocean beach.

Great density was reflected in the extremely narrow streets of Greco-Roman cities. Even the famous roads leading out of Rome, such as the Via Appia and Via Latina, were little more than paths, being about 16 feet wide. Within the city, Roman law required that streets be 9.5 feet wide, but many were much narrower than that.3 The main street of Antioch was admired throughout the empire for its spaciousness—it was 30 feet wide!4

Unlike dense modern cities such as Manhattan, which are very spread out vertically, Greco-Roman cities had no tall structures—usually no more than three stories. Even so, inhabitants lived in constant danger of having their tenements collapse for lack of adequate beams, to say nothing of the threat of falling down during earthquakes, which were very frequent in the eastern portion of the empire. And if tenements didn’t fall down, very often they burned. Although some temples and public buildings were built of stone, most structures were built of wood thinly covered with stucco, and they burned so well that many of these cities were often destroyed by fire and had to be rebuilt repeatedly upon the ashes. Hence, the “dread of fire was an obsession among rich and poor alike.”5 The threat of fire was increased by the fact that the chimney had yet to be invented, so all cooking and heating was done over insecure wood-or charcoal-burning braziers. The result was smoky rooms, but asphyxiation was usually prevented by the lack of window panes, windows being covered only with “hanging cloths or skins blown by [the wind.]”6 Of course, these drafts increased the danger of rapidly spreading fires.

As for sewers, except for several overcited examples of actual underground sewers flushed by running water, sewers in Greco-Roman cities were ditches running down the middle of each narrow street—ditches into which everything was dumped, including chamber pots at night, often from second-or third-story windows. We know this was a common practice because officials so often condemned it.7 As for water, it may have come to most cities via the picturesque Roman aqueducts, but once there it was stored in cisterns where it quickly turned “malodorous, unpalatable, and after a time, undrinkable.”8 In any event, except for a few of the wealthy to whose homes water was piped, everyone else had to lug water home in jugs from public fountains. That meant there was little water for scrubbing floors or washing clothes. It was a filthy life. And it stank! No wonder the ancients were so fond of incense.

Not only were these cities struck by deadly plagues, but less dramatic diseases were chronic. Sickness was highly visible on the streets: “Swollen eyes, skin rashes, lost limbs are mentioned over and over again in the sources as part of the urban scene.”9 In a time before photography or fingerprinting, written contracts offered descriptive information about the principal parties involved and “generally include[d] their distinctive disfigurements, mostly scars.” In one substantial collection of papyrus contracts examined by Roger Bagnall, all of the signers were scarred.10

In addition to physical misery, Greco-Roman cities suffered from high levels of social chaos. Because of their very high mortality rates, these cities required a large and constant stream of newcomers in order to maintain their populations. As a result, there always were a number of people who were unattached, and many of them eked out a living by victimizing others. Compared with even the most crime-prone modern cities, these cities were overrun with crime. “Night fell over the city like the shadow of a great danger, diffused, sinister, and menacing. Everyone fled to his home, shut himself in, and barricaded the entrance. The shops fell silent, safety chains were drawn behind the leaves of the doors…. If the rich had to sally forth, they were accompanied by [armed] slaves who carried torches to protect them on their way.”11 In addition, the constant influx of newcomers resulted in remarkable ethnic diversity in a time that was equally remarkable for its ethnocentrism. Diverse groups did not assimilate, but created and sustained their own separated enclaves—resulting in frequent turf conflicts and sometimes all-out riots and pogroms. At the same time, since (with the exception of Rome) Greco-Roman cities were so small, most people did not suffer from loneliness or alienation, but from the many burdens of living a too-intimate, insufficiently private life—the small town ‘claustrophobia’ that not long ago was still a principal literary theme.

And finally, disasters. Most of the cities examined later in this chapter were conquered by enemy forces, some of them many times. Antioch, for example, was conquered 11 times during a six-hundred-year span. Conquests sometimes resulted in such complete destruction that cities lay in uninhabited rubble for a time, as in the cases of Carthage, Corinth, and Antioch. In addition, many of these cities were effectively destroyed by earthquakes and fires, and deadly plagues swept through them periodically.

Because life in antiquity abounded in anxiety and misery, suffering played a substantial role in Christianizing the empire, but not in the way that has so often been claimed. Many have linked misery and anxiety to Christianization by supposing that in the third century things went from bad to worse, thereby spurring many to embrace the promise of eternal bliss offered by Christian teachings. In the words of E. R. Dodds, people turned to Christ out of revulsion “from a world so impoverished intellectually, so insecure materially, so filled with fear and hatred as the world of the third century, any path that promised escape must have attracted serious minds.” Dodds’s thesis, and all similar deprivation theories of the rise of Christianity, has two serious deficiencies. First, and most devastating, there is no evidence that conditions did get any worse in this era. As Peter Brown put it, too many modern historians have imposed a “false sense of melodrama” on this critical era.12 Indeed, as did Dodds, these historians rely heavily on “must have” assertions—people must have felt alienated from city life; they must have feared their increasingly despotic government; they must have longed for a life beyond death. But to say something “must have been” is not evidence. With Brown, I propose that the Christianization of the empire was not the result of “reactions to public calamity,”13 but to religious influences per se. That is, religion did not merely offer psychological antidotes for the misery of life; it actually made life less miserable!

The power of Christianity lay not in its promise of otherworldly compensations for suffering in this life, as has so often been proposed. No, the crucial change that took place in the third century was the rapidly spreading awareness of a faith that delivered potent antidotes to life’s miseries here and now! The truly revolutionary aspect of Christianity lay in moral imperatives such as “Love one’s neighbor as oneself,” “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” “It is more blessed to give than to receive,” and “When you did it to the least of my brethren, you did it unto me.” These were not just slogans. Members did nurse the sick, even during epidemics; they did support orphans, widows, the elderly, and the poor; they did concern themselves with the lot of slaves. In short, Christians created “a miniature welfare state in an empire which for the most part lacked social services.”14 It was these responses to the long-standing misery of life in antiquity, not the onset of worse conditions, that were the ‘material’ changes that inspired Christian growth. But these material benefits were entirely spiritual in origin. Support for this view comes from the continuing inability of pagan groups to meet this challenge.

In 362, when Emperor Julian launched a campaign to revive paganism, he recognized that to do so it would be necessary to match Christian “benevolence.” In a letter to a prominent pagan priest, Julian wrote: “I think that when the poor happened to be neglected and overlooked by the priests, the impious Galileans observed this and devoted themselves to benevolence…. [They]support not only their poor, but ours as well, everyone can see that our people lack aid from us.”15 But his challenge to the temples to match Christian benevolence asked the impossible. Paganism was utterly incapable of generating the commitment needed to motivate such behavior. Not only were many of its gods and goddesses of dubious character, but they offered nothing that could motivate humans to go beyond self-interested acts of propitiation. Indeed, many pagan temples were essentially ‘eating clubs,’ where a host furnished an animal to be sacrificed to the gods, after which the beast was cooked and eaten by the host’s many invited guests. (Temples employed skilled chefs.) The funds for this came from the host, while the setting—the temple and its priests—was provided mainly by wealthy donors, motivated at least as much by a desire to display their social status as by any religious concerns. And little or nothing was expected of the rank and file—nor could it be.

The Religious Context

To say that the Greco-Roman world was polytheistic is a gross understatement—the Greek poet Hesiod claimed there were 30,000 distinct gods.16 The precise pantheon of major gods differed somewhat from one city to another, but everywhere urbanites were confronted with a vast array. In most cities there were temples for from fifteen to twenty major gods, and additional temples or shrines for a mass of others.17 As Roger Brown put it so well, in this era people “lived in a universe rustling with the presence of many divine beings,” and, seen in perspective, even the early Christians occupied “an ancient, pre-Christian spiritual landscape.”18

In part, the classical world sustained many gods because each specialized in a limited range of abilities. But the larger part was played by the enormous ethnic and cultural diversity of imperial cities and the extensive amount of trade and travel across the empire—all of which not only spread local gods far and wide, but led to their recombination and amalgamation. This was well known in classical times. In his History, the Greek historian Herodotus (ca. 484–425 BCE) gave considerable space to comparing gods and rituals and suggesting how they might have spread, based on his personal travels to about fifty different societies. For example:

I will never believe that the rites [of Dionysus] in Egypt and those in Greece can resemble each other by coincidence…. The names of nearly all the gods came from Egypt to Greece…but the making of the Hermes statues with the phallus erect, that they did not learn from the Egyptians but from the Pelasgians, and it was the Athenians first of all the Greeks who took over this practice, and from the Athenians, all the rest.19

Perhaps the most fundamental aspect of Greco-Roman paganism was its inability to sustain itself by contributions from the rank and file. Most people were involved with too many gods to make significant contributions to any one of them, nor did they feel sufficient basis for doing so. Instead, the primary source of funding for paganism came almost entirely from a few very wealthy donors.20 As the empire expanded and the number of temples multiplied, the financial burden grew increasingly heavy and donations were divided among an ever-larger throng of gods.

As E. R. Dodds recognized, religious life in the empire suffered from excessive pluralism, from “a bewildering mass of alternatives. There were too many cults, too many mysteries, too many philosophies of life to choose from: you could pile one religious insurance on another, yet not feel safe.”21 Moreover, since no god could effectively demand adherence (let alone exclusive commitment), individuals faced the need and the burden to assemble their own divine portfolio,22 seeking to balance potential services and to spread the risks, as Dodds noted in his reference to religious insurance. Thus, a rich benefactor in Numidia contributed to temples and shrines honoring “Jove Bazosenus…Mithra, Minerva, Mars Pater, Fortuna Redux, Hercules, Mercury, Aesculapius, and Salus.”23 Ramsay MacMullen reports a man who simultaneously served as a priest in four temples,24 while many temples served many gods simultaneously.

Whereas competition within or among monotheistic faiths can result in strengthening each,25 within polytheism the greater the pluralism the weaker each particular temple was likely to become. Historians continue to puzzle over the fact that beginning in about 260 CE, “inscriptions proclaiming…whole-hearted private support to the cults of the traditional gods of the cit[ies]…wither[ed] away within a generation.”26 Following Michael Rostovtzeff,27 many historians have accepted that this was caused by a rapid economic decline of the Greco-Roman cities in this era. This is, of course, what one would expect historians steeped in materialism to conclude. However, a substantial number of subsequent studies, especially those based on specific cities, fail to reveal such economic declines.28 Indeed, the effects that earlier historians had “taken for the death throes of city life” now are regarded as “the growing pains” of urban evolution.29 Cities increased in size and in cultural diversity. And it was this diversity that seems the likely culprit in the decline of private donations to the temples. The common vision of a coherent set of a city’s gods was being lost, turning civic-mindedness in other directions. In other words, Greco-Roman paganism may have proliferated to the point that it was nearly overwhelming in its variety. This is not to suggest that paganism had thereby lost its credibility. As will be seen at length in Chapter 7, paganism didn’t just suddenly succumb to Christian persuasion or even to imperial suppression; vigorous paganism persisted well into the sixth and even the seventh centuries. But the rapid procession of new gods created a cultural fluidity that made it progressively easier for new faiths to gain a foothold: Chapter 4 demonstrates how the influence of Eastern faiths, such as worship of Cybele and of Isis, helped to prepare the way for Christianity.

Now, against this general background, it is time to be more specific about the contexts of the early church.

Cities of the Empire

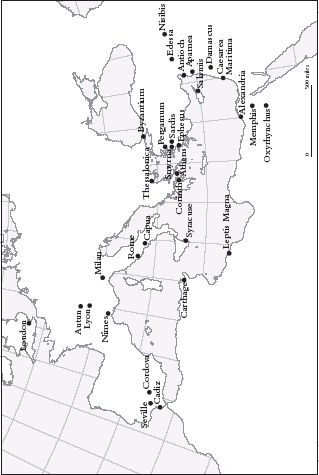

This book is based on the cities of the Roman Empire. But which ones should be included? One might suggest including all places that were large enough to leave historical traces. However, even in this era when cities were very small, it would be unreasonable to count a place with 1,000 residents as a city, even by the standards of the time.30 Worse yet, the actual populations of ancient cities are very difficult to determine. Back then, even local officials probably had only crude estimates, although probably not as crude as some used by historians for generations, which accounts for the many extraordinary variations in the figures offered by reputable scholars. Did Rome have a million residents or only 200,000?31 Were there 8,000 or nearly 24,000 inhabitants of Tiberius?32 Did Carthage and Antioch each have “over 500,000”33 residents or only one-fifth that many?34 As for Pergamum, Encyclopaedia Britannica says its population was 200,000, while Tertius Chandler places it at only 40,000.35 Fortunately, in recent years considerable attention has been paid to reconstructing ancient populations from such things as archaeological evidence. These data are, of course, far from precise, but they are sufficient for our needs.36 Assuming that 30,000 residents is a reasonable minimum city-size, there were thirty-one cities of that size or larger within the Roman Empire in the year 100 CE. They stretched from London in the west to Nisibis in the east and Oxyrhynchus in the south, as is shown in Map 2-1. Since these thirty-one cities will be the basis for all subsequent analysis, it seems useful to offer a thumbnail sketch of each.

It might be supposed that a study such as this would begin with the city of Jerusalem. However, as of the year 100, Jerusalem had only a small population, having been smashed, burned, and sacked by the Roman army in 70; and it would be almost completely depopulated again when razed by Hadrian in 135. Of course, there will be frequent references to Jerusalem throughout the book, but it does not qualify as one of the cases to be included in the analysis.

The Near East

It does seem appropriate, however, to begin with the imperial cities of the Near East, those closest to Jerusalem.

CAESAREA MARITIMA. Population: 45,000. Located about sixty miles north of Jerusalem, Caesarea was built by Herod the Great, who named it in honor of Caesar Augustus.

Construction began about 22 BCE and was completed twelve years later. As would befit a king’s whim, it was a beautiful city made of white marble, in the midst of which, on a hill, stood one of the earliest temples dedicated to the Imperial Cult that elevated some emperors to divinity. This splendid temple contained two large statues of Augustus. But the city’s most remarkable feature was the harbor. The site had no natural harbor, not even an inlet, but was a barren beach on a dangerous coast. Herod had a large harbor constructed in 20 fathoms of water by building two moles (or breakwaters) extending 1,600 feet into the sea. The moles were constructed of masonry blocks 50 feet long, 18 feet wide, and 9 feet thick, made of a specially invented concrete that would harden under water. To create a block, a wooden box was floated to the desired position and then sunk. The mortar was poured into the submerged box through a wooden tube with flexible leather joints and left to harden. A gap 60 feet wide between the two moles provided an entrance to the harbor. When completed, the moles were from 150 to 200 feet wide, adequate to stop even very high stormy seas; in addition, they provided space for many warehouses and served as a pier for unloading.37

Caesarea figured prominently in early Christian history. Pontius Pilate made Caesarea his headquarters and wintered his legions there. Paul and his companions passed through the port on their return from several missionary journeys, and later Paul was held captive there to await being sent to Rome. The early church father Origen lived there for about twenty years, as did his student Eusebius, the remarkable first church historian who also served as bishop of the city.

DAMASCUS. Population: 45,000. For Christians, the road to Damascus greatly overshadows the city itself. Yet it is one of the oldest cities in the region, mentioned both in Genesis (14:15; 15:2) and on clay tablets dating from 2400–2250 BCE found at Ebla. Damascus is located at an oasis sixty miles from the Mediterranean and is surrounded on three sides by desert. In addition to a number of springs, several rivers pass by, providing sufficient water for an abundant agriculture. A number of major caravan routes crossed at Damascus, making it a commercial center. Given its location and lack of any natural defensive features, Damascus was incorporated into one ancient empire after another: Egyptian, Hittite, Aramean, Hebrew, Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, Seleucid, and finally Roman. Although Damascus served for a time as the capital of the Seleucid Empire (founded by Greeks who had served with Alexander the Great), it soon was eclipsed by Antioch, which was founded by the Seleucids to exploit its far superior strategic location. Pompey conquered Damascus in 64 BCE and incorporated it into Rome’s province of Syria. Roman rule allowed rapid expansion of the local Jewish community.38

Christianity must have come very early to Damascus, since Paul (Saul) was on his way there to stop Christian missionizing among the Jews when he had his dramatic conversion experience.

ANTIOCH. Population: 100,000. Sometimes called Syrian Antioch, this city was founded around 300 BCE by Seleucid rulers wanting to take advantage of its strategic location on the Orientes River where it cuts through the mountains: “Antioch stands at the focal point for communications with Palestine to the south…and with the Euphrates to the east.”39 After Antioch was annexed by Rome in 64 BCE, the emperors regarded it as of such strategic importance that they rebuilt the city and resettled it with veterans each time it was destroyed—by earthquakes, fires, and war.40 Unfortunately, the city was equally susceptible to internal disasters. Rioting was chronic as various ethnic enclaves attacked one another.

The Diasporan Jewish community in Antioch was old and large, but its first members weren’t migrant Jewish merchants, as in many other cities, but Jewish veterans retired from the Seleucid army.41 In the year 40 CE Emperor Caligula declared himself a god and ordered that his statue grace the temple precincts in Jerusalem. Following Jewish protests against sacrilege, organized mobs burned the synagogues in Antioch and murdered a large number of Jews. A few years later, the Jewish Revolt in Palestine led to even worse riots and more Jewish fatalities.

Meanwhile, some Jews in Antioch became Christians, as did some Gentiles, thus giving urgency to the issue of “uncircumcised” converts. With that issue resolved by a ruling from Paul, what probably was the first Christian church with a substantial Gentile membership came into existence here. In fact, this fortress city was second only to Jerusalem as the most important setting in the early history of Christianity.42 Paul used Antioch as his home base, and it was from here that he set out on his three missionary journeys. According to Acts (11:26), it was in Antioch that the name Christian was coined by city officials needing to distinguish Jesus’s followers from Jews and pagans.

APAMEA. Population: 37,000. Located south of Antioch on the route to Damascus, Apamea was long a part of the Seleucid Empire and, along with Antioch, served as its major gateway for trade to the West. In 64 BCE Pompey imposed Roman rule on the area. According to Josephus, as Pompey marched to Damascus he “demolished the citadel that was at Apamea.”43 Subsequently, the city joined in Syria’s revolt against the empire and held out for three years against the Romans, finally falling to Cassius in 46 BCE.44 Even after coming under Roman rule, Apamea remained a very Hellenic city in terms of its culture. Paul probably passed through Apamea on his way back to Antioch at the end of his second missionary journey, but there is no indication that he stopped to visit. However, a Christian congregation was established here by early in the second century.

SALAMIS. Population: 35,000. The principal city of ancient Cyprus, Salamis was on the east coast of the island, north of modern Famagusta. It is not to be confused with the small Greek city also named Salamis, just off the coast of Athens, where the Persian fleet was drawn into the narrow strait and destroyed by the Greeks in 490 BCE. This Salamis on Cyprus was, however, the site of a naval battle of almost equal magnitude when, in 360 BCE, a Greek and Egyptian fleet was sunk by Macedonians.

In peacetime Salamis was, for centuries, a busy port and a major commercial center. Not surprisingly it attracted a Diasporan community of sufficient size and significance to be mentioned in Acts (13:5). Like many cities in this region, Salamis was often nearly destroyed by natural and military disasters. Finally, in 648 Salamis was attacked and destroyed by Arabs and has since remained an abandoned ruin.

Mesopotamia

Let us now venture off to the northeast of the cities described above, where two of our cities were located in what was then Mesopotamia.

EDESSA. Population: 75,000. This is one of the most easterly of the larger Roman cities. Over the centuries there probably were many settlements on this site, but Edessa was founded in about 303 BCE by Seleucus I Nicator, who had been one of Alexander the Great’s officers. Subsequently, Edessa was ruled by the Parthians, who were vanquished by the Romans. Located on the River Scirtus (a tributary of the Euphrates), the city was subject to repeated devastating floods and frequent earthquakes. A great flood in 201 CE destroyed most of the city, including its Christian church.45

Because the ruling prince probably was baptized late in the second century, Edessa may have been the first Christian ‘state,’ and a substantial body of Christian writings appeared here translated into Syriac (including the Peshitta, a Syriac version of the New Testament). Subsequently, Edessa produced Gnostic literature and the Nestorian Heresy, which proposed that Mary ought to be referred to only as the “Mother of the Christ,” not as the “Mother of God,” for which its founder had to flee to Persia. Edessa is mentioned in Revelation (2–3) as one of the places where Christian communities made an early appearance.

NISIBIS. Population: 67,000. There was a very ancient city on this site, which is located to the northeast of Edessa—some even have associated that city with those referred to in Genesis. However, the Nisibis of New Testament times was refounded by Macedonians and was a solidly Hellenic rather than Persian city. Indeed, it stood as a frontier stronghold against eastern incursions, first under the Seleucids and then as part of Rome. In the early days of Roman rule the city was often lost to and retaken from the Parthians. It was strengthened by Trajan, and Septimius Severus made it his headquarters when campaigning in the East. Thus, Nisibis served as “the advanced outpost of the Romans against the East”46 until it was lost again to the Persians as a result of Julian’s abortive fourth-century offensive. Although there was no significant Diasporan Jewish community in Nisibis, it had a Christian church by the second century.

Asia Minor

Let us now turn west to the cities of Asia Minor, in what today is Turkey.

PERGAMUM. Population: 40,000. This Grecian city, sixteen miles from the Aegean Sea, was “easily the most spectacular city of Asia Minor.”47 It began as a fortress situated atop a hill that rose 900 feet above the surrounding plain. In about 330 BCE, the Attalid dynasty added a palace on the hilltop, and then a temple to Athena. Eighty feet down the hill was built a Great Altar of Zeus, and on the other side of the hill a fine theater was located. The Attalids also founded a great library with a reading room about fifty feet square (which has been excavated), said to have included 200,000 volumes of parchment. In fact, when the Egyptians would not export papyrus, parchment (made from treated animal skins) was invented in Pergamum. The word parchment derives from the Latin “Pergamena charta,” or “paper of Pergamum.” During their stay in Pergamum, Mark Anthony gave the library to Cleopatra.48 Whether she was able to move the library to Egypt to be merged with the great library at Alexandria is not known. If she did, then nearly everything written in classic times, papyrus and parchment, was destroyed during the various disasters that beset the library in Alexandria.

Under Roman rule, which began in 133 BCE, Pergamum served as the capital of ‘Asia’—eventually to be replaced by Ephesus. Meanwhile, the city greatly expanded at the bottom of the hill, and many new temples were built. The most significant of these was dedicated to the Imperial Cult. “Here was built the first Asian Temple of the divine Augustus, which for more than forty years was the one centre of the Imperial religion in the whole Province. A second Asian Temple had afterwards been built in Smyrna, and a third at Ephesus; but they were secondary to the original Augustan Temple at Pergamum.”49 In addition, of course, Pergamum was one of the “seven churches of Asia” named in Revelation (1:11; 2:12). Christianity arrived here in the first century, perhaps brought by missionaries trained by Paul at nearby Ephesus.

EPHESUS. Population: 51,000. Remarkable feats of engineering kept the harbor at Ephesus from silting up, a chronic problem for all Mediterranean ports at the mouths of rivers because the very small tides are inadequate to scour them out.50 (Today the city is five miles from the sea.) But even more remarkable engineering was required to construct the Temple of Artemis (Diana) on landfill. Having 128 pillars sixty feet high, it was so huge a structure that it was regarded as one of the “seven wonders of the world.” The splendor of the temple is attested by one of the most famous statues from ancient times—that of the goddess Artemis depicted with rows of breasts—which is believed to have come from the temple.

Ephesus enjoyed a lucrative tourist business from pilgrims to the temple, but it profited even more by lending money from the “enormous wealth deposited in the temple itself.”51 According to the Greek philosopher Dio Chrysostom, the temple also served as a bank of deposit; even kings, he said, “deposit there in order that it may be safe, since no one has ever dared to violate that place.”52 Of course that didn’t stop Julius Caesar from robbing the temple during the civil war of 49–46 BCE.

When Paul arrived, there already was a functioning Christian congregation, perhaps based on a group that had been committed to John the Baptist and converted to Christ by Aquila and Priscilla. Paul remained for about three years helping to build up the congregation and to train and dispatch missionaries to found congregations in other towns and cities in the area.53 Various early church fathers, including Irenaeus and Clement, attested that the Apostle John died and was buried in Ephesus,54 though that fact was not mentioned in Acts.

Ephesus was seized by the Romans following their victory over the Seleucids at the Battle of Magnesia and assigned to Pergamum. About fifty years later the Romans took direct control of the city. Mark Antony and Cleopatra spent the winter of 33–32 BCE in Ephesus.

Nero rebuilt the stadium at Ephesus, but like Caesar he also looted the great temple. Domitian had a large temple constructed in Ephesus and dedicated it to himself as a god. Trajan also built a temple to himself here, and Hadrian claimed that Ephesus was his favorite city and made it the capital of Asia, replacing Pergamum, for which the city built him a temple too. Today the city is one of the finest excavated sites in Turkey.55

SARDIS or SARDES. Population: 100,000. It was in Sardis, somewhere around 670 BCE, that the very first metal coins were minted, made of electrum, an alloy of gold and silver. Soon after, the first pure gold and silver coins were struck. In those days, Sardis was part of the Lydian kingdom, and its most famous king was Croesus, celebrated for his immense wealth from the fabulous amounts of gold panned from a nearby stream. Ancient tradition concerning the abundance of gold in Sardis was confirmed in 1968, when archaeologists found nearly three hundred crucibles for refining gold.56

As it turned out, Croesus was the last of the Lydian kings, Sardis having been captured by Cyrus the Great of Persia in 546 BCE. Historians disagree as to whether Croesus was executed or spared. The city remained Persian until taken by Alexander the Great. It came under Roman control in 133 BCE. The city was destroyed by an earthquake in 17 CE but was very quickly rebuilt by Emperor Tiberius, whose restoration efforts led to a major outbreak of emperor worship.57

The patron deities of the city were Cybele and Artemis. Both seem to have fostered highly sexually charged rites—for example, Cybele was served by priests who castrated themselves during frenzied celebrations and then wore feminine costumes, makeup, and jewelry.58 Christianity arrived in the first century.

SMYRNA. Population: 90,000. Smyrna was situated on the coast, thirty-five miles north of Ephesus. It was destroyed and rebuilt several times. When Alexander the Great rebuilt it in the fourth century BCE, the site seems to have been nothing but ruins. Soon Smyrna was known as the “ornament of Asia,” and in 195 BCE it became the first city in Asia to “erect a temple for the cult of the city of Rome.”59 Later came temples for both Tiberius and Hadrian. There also was a sizable Diasporan community in Smyrna and a very early and very active Christian community. In 117, when Bishop Ignatius of Antioch dispatched letters during his trek to Rome, one of them went to Bishop Polycarp of Smyrna, who would eventually be martyred in Smyrna’s stadium.

BYZANTIUM or CONSTANTINOPLE. Population: 36,000. Destined one day to be the huge, glittering capital of the eastern empire, at the end of the first century Byzantium was a relatively small city, having been founded six centuries earlier by Greeks from Miletus and Megara. Situated at the eastern frontier, the city was “engaged in perpetual warfare with the neighbouring barbarians.”60 In fact, the Persians took the city in 512 BCE. However, it was taken back by the Athenians in 496 BCE. In 343 BCE the city allied itself with Athens, and together their forces defeated Philip II of Macedonia when he tried to capture Byzantium in 340 BCE. The city could not withstand his son, however, and accepted rule by Alexander the Great without resistance. As Grecian power faded, Byzantium came under Roman rule. Then, in 196 CE, Byzantium sided with the usurper Pescennius Niger against Emperor Septimius Severus. As a result, Severus took the city, killed its inhabitants, and reduced Byzantium to ruins. Severus soon realized the strategic importance of this location and had the city rebuilt. It continued to flourish, and its beautiful site led Constantine to make Byzantium his capital city, renaming it after himself at the formal inauguration in 330.

North Africa

From Asia Minor we move to the cities of North Africa.

ALEXANDRIA. Population: 250,000. Founded in 331 BCE by Alexander the Great, it became the capital of Egypt under the Ptolemaic dynasty and developed into “the busiest port in the ancient world,”61 exporting immense amounts of wheat to feed Rome. Rome’s dependence on Egyptian wheat led to Roman rule in 80 BCE, but Roman control greatly increased after Octavian’s victory over Mark Anthony and Cleopatra in 30 BCE.

With its huge library and collection of famous scholars, including Euclid, Eratosthenes, and the Jewish philosopher Philo, Alexandria was the intellectual center of the Greco-Roman world. But it was even more important as a religious center. Here a very large Jewish population mingled with an unusually vigorous paganism. It was in Alexandria that the Old Testament was translated into Greek (because the local Jews had mostly lost their Hebrew) and here too that a host of apocryphal books were written.62 Alexandrian paganism was equally creative, combining Egyptian and Greek gods and rites in innovative ways, and exporting new gods and faiths to the rest of the empire. In the first century, Alexandria’s pagans and Jews were confronted by a rapidly growing Christian community. According to tradition, St. Mark is credited with bringing Christianity to the city, and he is believed to have been martyred there in the year 62 for preaching against the worship of Serapis, a god paired with the goddess Isis and first heard of in Alexandria (see Chapter 4). The story of St. Mark’s death is probably mythical, but no doubt it served to inspire subsequent generations of Alexandrian Christians.

MEMPHIS. Population: 50,000. One of Egypt’s most ancient cities, Memphis was the first capital of the United Kingdom of Upper and Lower Egypt. Located where the Nile divides on its way to the sea, Memphis was placed on the west bank so that the river served as a defensive barrier against invaders from the east (the desert to the west being devoid of significant enemies). Memphis is the location of the great pyramids and the Sphinx, and in ancient times the city abounded in splendid temples. Many centuries later, when Egypt came under Greek rule, it was in Memphis that Alexander the Great’s body was given temporary burial, before being moved to Alexandria. By the time of Roman rule (first century BCE), the city was rather decayed. Today it lies in ruins, thirteen miles south of Cairo.

Memphis is mentioned once in the Old Testament but never in the New, the city having lost much of its importance by that time. However, a Christian church existed in Memphis by the second century, having come up the Nile from Alexandria.63

OXYRHYNCHUS. Population: 34,000. Named for a fish of the sturgeon species, which was an object of local worship, this Egyptian city on the western bank of the Nile has been nearly forgotten by history. It rates a brief paragraph in Encyclopaedia Britannica only because of the discovery of a huge cache of ancient papyri here at the start of the twentieth century. Included were copies of long-lost classics of Greek literature as well as many Gnostic and apocryphal books. The most significant find probably was a fragment of the Gospel of John, dated about 125 CE, which suggests the presence of a Christian congregation in Oxyrhynchus by that date. In all, about 40,000 pieces were unearthed here, including several thousand complete documents. Although, before being overrun by Islam, Oxyrhynchus was an Episcopal See, its fame was as a center of monasticism, with as many as 10,000 resident monks. That undoubtedly is why such an accumulation of buried papyri existed here. The city also attracted and sustained a number of Gnostic writers, whose manuscripts were likewise among those recovered, including three Greek manuscripts of the strange Gospel of Thomas, a document that, a century after the discovery of that papyrus, has been touted by an Ivy League professor as a suppressed document that reveals the ‘true’ Christianity.64

The Romans operated a mint in Oxyrhynchus, but today there are only some ruins and a small Egyptian village at this site.65

LEPTIS MAGNA or LEPCIS. Population: 49,000. Located on the North African shore, about two-thirds of the way from Alexandria to Carthage, Leptis Magna was founded in about 600 BCE by the Phoenicians. Subsequently, it became part of the Carthaginian Empire, and after the fall of Carthage it was incorporated into Roman Africa. At its height, during the first through third centuries, Leptis Magna was a major port exporting grain and olives from its fertile hinterland. It was a wealthy city, and this was reflected in its architecture: many colonnaded avenues, a magnificent theater and sports field, massive baths, and beautiful temples. As the birthplace of Septimius Severus, who was emperor of Rome from 193 to 211 CE, it enjoyed a period of great imperial favor. During that time there was much refurbishing and additional construction, including the four-way triumphal Arch of Severus, made of the best marble. As Roman strength in Africa waned, Leptis Magna was repeatedly sacked by raiding Libyan tribes and then by the Arabs. What its enemies started, nature finished: soon most of this beautiful city was covered by sand, and it seldom is mentioned in histories of its time. Today it is one of the premiere archaeological sites, with most of the city remaining unexcavated.66

CARTHAGE. Population: 100,000. Rome’s deadliest enemy was situated on the north coast of Africa. The city was originally founded by Phoenicians, who over many centuries built an empire in Africa and the islands of the Mediterranean to rival that of Rome.

This threat to Roman power led to the Punic Wars. The first of these began in 264 BCE and ended in 241 with a treaty favorable to Rome, but both sides soon violated their agreement: Rome by seizing Sardinia and Corsica, Carthage by invading Spain. The second Punic War broke out in 218 BCE and lasted for seventeen years. After the famous Carthaginian General Hannibal Barca led an elite army of about 40,000 soldiers and a number of elephants on an overland march from Spain, over the Pyrenees, across Gaul, and over the Alps, most of the fighting took place in Italy. For many years, Hannibal won the battles, but he couldn’t win the war because Rome kept raising new legions. Finally, Hannibal was forced to withdraw his army to Carthage to head off a Roman invasion. He lost a battle in front of the city, and Carthage surrendered in 201, though many Romans rejected the settlement. For years, Cato the Elder greeted every opening of the Senate with the pronouncement “Carthage must be destroyed.” And so it was. The third Punic War was initiated by Rome in 146 BCE and ended in a house-by-house conquest of the city, all of its inhabitants being killed or sold into slavery, every building razed, the city plowed up, and salt sown in the soil.

A century later Julius Caesar formulated plans to refound Carthage, but he was murdered before they could go forward. So, two years later, in 44 BCE, Carthage was refounded by Emperor Augustus to serve as Rome’s administrative center for the region, taking advantage of its strategic location. Augustus sent 3,000 Roman colonists, and they were joined by many people from the immediate area. The city grew very quickly, and Carthage soon regained its position as an important trading center. Christianity arrived early in the second century, probably from Alexandria.

Greece

Three cities in Greece also are included in this set.

ATHENS. Population: 75,000. Although Athens proper was located about five miles from the Mediterranean, the city walls extended all the way to the water and encircled three harbors, which allowed Athens, at its height, to be a major sea power and a busy port. Of course, it was best known as the intellectual capital of ancient Greece. However, by the time of Paul’s visit in the first century, “Athens was well past its prime, living on bygone glories, rich in monuments but an intellectual desert compared to what once had been.”67 Athens’s human population was less than a third of what it had been in Plato’s day, but the population of gods had continued to grow. There were temples everywhere, including one “to an unknown god.”68 During his stop in Athens, Paul used this opportunity to inform the local intellectuals of the identity of their unknown god, whom he presented as the One True God of the Jews and Christians. The Athenian philosophers were not receptive, and according to Acts, Paul left the city disappointed and convinced that in the future he would not waste time with philosophy, but would stick to the gospel message.69

CORINTH. Population: 50,000. Despite its great prominence in early Christian history, Corinth was a “brawling seaport…being notorious for its blatant immorality. Much of its population was transitory—sailors, freebooters, adventurers, swindlers of every sort.”70 Corinth’s great commercial advantage came from its location on a narrow isthmus, which offered a very substantial shortcut for westbound shipping from most other Greek ports, including Athens and Thessalonica. Rather than making the long voyage around the large Peloponnesian Peninsula, boats were off-loaded at Corinth and their cargoes hauled a few miles overland to the Adriatic, there to be reloaded and sent on. Sometimes the ships themselves were dragged overland and relaunched!

In 146 BCE Corinth served as headquarters for the Achaean League, which rashly challenged Roman rule. The league was quickly defeated by the Roman Consul Lucius Mummis. As a lesson to all, Corinth’s citizens were slaughtered or sold into slavery, and the city was burned and reduced to rubble. The Romans then devoted the site to the gods and prohibited any human habitation. But it was too good a site to be abandoned: in 46 BCE Julius Caesar had Corinth rebuilt and settled with a mixture of retired veterans of the legions and thousands of Rome’s ‘undesirables.’ The results were predictable: “It was the most licentious city in all Greece; and the number of merchants who frequented it caused it to be the favorite resort of courtezans. The patron goddess of the city was Aphrodite, who had a splendid temple…where there were kept more than a thousand sacred female slaves for the service of strangers.”71

It was here that Paul spent eighteen months and built up a congregation of both Jews and Gentiles. Historians have long attributed his success to the dreadful situation of the city’s poor. As recently expressed: “It was primarily among the miserable poor that Paul found a positive response to his preaching.”72 And, as usual, 1 Corinthians 1:26 was cited as proof: “[N]ot many of you were wise according to worldly standards, not many were powerful, not many were of noble birth.” However, as E. A. Judge suggested, substitute the word “some” for the words “not many” and the implications of this verse change dramatically. In a Roman world where the aristocracy “amounted to an infinitesimally small fraction of the total population,”73 Paul is acknowledging that his small congregation in Corinth included “some” of noble birth and “some” who were powerful. Indeed, scholars now agree that among Paul’s members at Corinth was Erastus, “the city treasurer,”74 and in his remarkable studies of the church at Corinth, Gerd Theissen has identified other members of the “upper classes.”75 This was not unique; all across the empire Christianity was a movement of the more privileged.76

THESSALONICA. Population: 35,000. Although located in mainland Greece on a great natural harbor at the head of a large gulf on the Aegean Sea, Thessalonica was nothing but a collection of tiny villages until Alexander the Great’s brother-in-law Cassander founded a city there and named it after his wife. The city grew very rapidly, and its economic life continued to prosper under Roman rule, which began in 168 BCE.

As a boom town having a large transient population of sailors, merchants, travelers, and soldiers, Thessalonica developed “a profuse…religious life, as foreign cults put down roots alongside the more traditional philosophic schools and indigenous forms of worship.”77 In 1917 a large temple devoted to Isis was excavated, dating from the third century BCE. Other Egyptian gods also were represented in the city, including Anubis.

Paul and his group of missionaries added to this exotic mix when they arrived in Thessalonica about 50 CE or earlier. The Christian mission seems to have been quite successful, but as usual the Christians soon came into conflict with the Diasporan community. To deflect attacks on his host, Jason, Paul withdrew to a nearby town. But because the attacks continued, Paul departed, leaving Silas and Timothy behind to continue the mission.78 Once back in Corinth, following his visit to Athens, Paul wrote79 two remarkable letters to the growing church in Thessalonica. He did so to head off the kinds of misunderstandings and conflicts that are inevitable in a new religious community. No one has put this so well and so gracefully as Arthur Darby Nock:

The letters to the Thessalonians give us a notable picture of the human failings of a new community. There were misunderstandings of the doctrine which had been so recently imparted; there were almost certainly divisions; the leaders on the spot were perhaps a little too anxious to exercise authority and somewhat lacking in tact, while on the other hand, some of the rank and file, in their confidence in the Spirit which they were said to have received, were reluctant to submit to any direction; again, moral problems did not disappear overnight.80

To deal with all these problems, Paul had to write a lucid primer of basic Christianity as he understood it, thereby providing a priceless legacy to all subsequent generations.

Italy

Now to Italy (and Sicily).

ROME. Population: 450,000. It seems pointless to devote much prose to the geography or history of the most famous city of ancient times, but something can usefully be reported about its Christianization.

There is no record of missionaries going to Rome. Although both Peter and Paul were executed in Rome, there was a substantial congregation in the city long before either of them arrived. A persuasive clue as to how Christianity arrived in Rome comes at the end of the Epistle to the Romans (16:3–16). Despite never yet having been to the capital, Paul greeted a number of old friends in the congregation.81 This prompted Nock to propose that the “Christian community in Rome seems to have come into being without any missionary act—simply as a result of the migration of men [and women] from Palestine and Syria.”82

However, these migrants must have engaged in a great deal of rank-and-file missionizing once they reached Rome, since the congregation soon included not only many Romans, but among them some members from the upper strata of Roman society. Historians now accept that Pomponia Graecina, a woman of senatorial class, accused in 57 of practicing a “foreign superstition,” was a Christian. Nor, according to Marta Sordi, was she an isolated case: “We know from reliable sources that there were Christians among the aristocracy [in Rome] in the second half of the first century (Ancilius Glabrio and the Christian Flavians) and that it seems probable that the same can be said for the first half of the same century, before Paul’s arrival in Rome.”83 Consequently, at the end of the first century, when Ignatius, bishop of Antioch, was arrested and led to Rome for execution in the arena, his special fear was that the Roman Christians would interfere with his desire for martyrdom and obtain his pardon. So he wrote to them: “The truth is, I am afraid it is your love that will do me wrong. For you, of course, it is easy to achieve your object; but for me it is difficult to win my way to God…. Grant me no more than that you let my blood be spilled[;]…do not interfere. I beg you, do not show me unseasonable kindness.”84 Ignatius’s concerns would have been silly had he not known that the Christians in Rome probably could have saved him.

CAPUA. Population: 36,000. Located south of Rome and just north of modern Naples, Capua was situated on an open plain, lacking any natural defensive features. It was the capital of the region known as Campania. In about 300 BCE Capua was linked to Rome by the Via Appia, probably the most important military highway in Italy. It was a very rich city, renowned for luxurious lifestyles, and it also was the home of many gladiatorial schools—Spartacus and his followers were trained there. In fact, as with Spartacus, Capua had a long history of backing losers. During the Punic Wars, Capua defected to Hannibal, and he wintered his army nearby, for which Rome later punished some civic leaders. Then the city became involved with a colonizing scheme led by Brutus. In 69 CE Capua backed Vitellius, whose corrupt and debauched rule as emperor lasted less than a year.

Although it had a small Jewish community, Capua probably did not get a Christian church until the reign of Constantine.

SYRACUSE. Population: 60,000. Located on the southeast coast of Sicily, Syracuse had a magnificent port and a history of intrigue, assassination, revolt, repression, and general bloodiness that was exceptional even for ancient times. Having two harbors, one of them among the largest on the Mediterranean (guarded by two islands), Syracuse was coveted by empire-builders throughout the centuries. Internal conflicts began soon after the city was founded by Corinthians in 734 BCE.85 Thucydides mentioned the expulsion of a faction in 648 BCE, and in his Politics Aristotle mentioned a subsequent, similar event.86 Around this time Syracuse attempted to sustain democracy and adopted the Athenian practice of “petalism,” wherein every man wrote on an olive leaf the name of the most powerful citizen: the one receiving the most votes was banished for five years. But democracy had a very rocky and intermittent existence in Syracuse.

Frequently attacked from the sea by various Greek and Carthaginian erstwhile invaders, the city usually was up to the test, but its domestic rule amounted to serial murder. For example, in 317 BCE a general named Agathocles obtained mob approval for appointment as head of state by slaughtering the six hundred richest citizens. He is remembered as “a good ruler,” but eventually he lost his popularity and was murdered by his nephew.87 The subsequent period of anarchy was ended in 288 BCE by Hicatas, who was killed and replaced by Tinion eight years later. At the start of the Punic Wars Syracuse allied itself with Rome. However, in 216 BCE Hieronymus led the city to support Hannibal, an alliance that was continued even after Hieronymus was murdered by a popular government. Consequently, two years later Claudius Marcellus laid siege to Syracuse and in 212 BCE sacked the city. Syracuse then became the Roman capital of Sicily and remained so until Byzantium took the island.

Local tradition holds that Peter brought Christianity to Syracuse, but historians think it most likely that Christianity did not arrive here until early in the second century.

Gaul

We now move northward to Gaul.

MILAN or MEDIOLANUM. Population: 30,000. Located on the only broad, fertile plain in Italy, near the foot of the Alps, Milan was the capital of Cisalpine Gaul. Before being conquered by the Romans, it was merely a village—as were all Gaulish settlements. It was annexed by Rome in 190 BCE, and its residents were made full citizens of Rome in 49 BCE. Milan rapidly became the largest and most important city in northern Italy, and all of the major roads north crossed here. Thus, it was so strategically located for directing Roman forces against barbarian threats that, beginning with Augustus, Roman emperors spent considerable time in the city. In 303 CE Maximian took up residence in Milan, as did many subsequent emperors. Christianity probably did not establish a congregation here until sometime in the third century.

AUTUN or AUGUSTODUNUM. Population: 40,000. Located in central France (southwest of Dijon), it was founded by its namesake, Emperor Augustus, on the site of a city called Bibracte (after a local goddess) by Caesar in his Commentaries. Built as a fortress city encircled by stout masonry walls, Autun was renowned in Roman times for its schools of rhetoric, which educated the sons of nobility from all over Gaul.88

Though there seems not to have been an organized Christian congregation in Autun until after the year 200, a marble gravestone found there in 1839 is regarded as one of the important archeological finds concerning the early church. Known as the Inscription of Pectorius, it consists of eleven verses in Greek, which refer to Christianity as “the Fish,” and describe the Eucharist while acknowledging “the Redeemer” and the “Lord Savior.” Scholars date the gravestone to the third century or early fourth.89

LYON or LUGDUNUM. Population: 50,000. Located in southern France at the juncture of the Rhône and the Saône rivers and at the end of several major routes across the Alps, Lyon began as a Roman military colony in 43 BCE. Over time a city grew up around the legion outpost and Emperor Augustus made it the capital of all Gaul, building a number of roads that converged on the city. Consequently, it became a very cosmopolitan city, and the largest in Gaul, drawing merchants and traders from distant places. The city was destroyed by fire during the first century and was restored by Nero, whom the city had supported when Galba challenged Nero’s reign.

By early in the second century “the first Christian community of Gaul was established” in Lyon.90 In 177, during the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the Christians of Lyon were brutally persecuted. Eusebius devoted many pages to reporting the savagery of both the mob and the governor toward these “martyrs of Gaul.”91

Then, in 197, Lyon bet on the wrong contestant for emperor, as so often happened to Roman cities. When Albinus was defeated by Septimius Severus, the winner directed his troops to sack the city and had the leading citizens put to death. Severus also destroyed Lyon’s aqueducts, hastening the city’s decline.

NÎMES or NEMAUSENSIS. Population: 44,000. After Lyon, Nîmes was probably the second richest and most important Roman town in Gaul. Located southwest of Lyon, it was founded by Emperor Augustus on the site of a village that served as the capital of a Gallic tribe that had submitted to Rome in 121 BCE. Augustus named the city Nemausensis after the genie of a sacred fountain.

Augustus not only founded the Roman city and gave it many political privileges, but he also funded a lavish construction program. Most of the resulting structures are still standing: a huge amphitheater with seats for 24,000; a large temple dedicated to Augustus’s adopted sons; city walls that include a tower nearly 100 feet high; a magnificent Temple of Diana that was connected to the baths; and a great aqueduct known as the Pont du Gard.

There was no Diasporan community in Nîmes, and Christianity arrived there quite late as well.

Spain

Three Spanish cities are included.

CADIZ or GADIR or GADES. Population: 65,000. This coastal city at the southern tip of Spain, beyond the Pillars of Hercules (the Strait of Gibraltar), was founded by the Phoenicians. “To the Greeks and Romans it was long the westernmost point of the known world.”92 Cadiz has a remarkable location, being surrounded by the sea except for a tiny spit connecting it to the mainland. After the Phoenician era, Cadiz became a major Carthaginian port before surrendering peacefully to Rome at the end of the second Punic War (about 200 BCE). Throughout its history, Cadiz has been a city of seafarers. In fact, the remarkable English historian William Smith suggested that Cadiz usually was “not densely peopled, since a large part of the citizens were always absent at sea.”93 Strabo, the early Greek geographer, reported that the imperial census taken under Augustus revealed that Cadiz had a higher proportion of rich citizens (equites) than all but one other Roman city (Patavium), due no doubt to its lucrative trading activities.94 The city also had a famous oracle and unusually splendid temples, especially those devoted to Saturn and Hercules.

CORDOVA. Population: 45,000. Founded in 152 BCE by Roman colonists, Cordova is situated northeast of Cadiz on the very navigable Guadalquivir River. Cordova was on the wrong side in the war between Julius Caesar and Pompey. Having been defeated repeatedly elsewhere in the empire, the Pompeian forces fled to Spain and assembled thirteen legions. Caesar landed with eight legions and annihilated the Pompeians at Munda in 45 BCE. In the aftermath Caesar took Cordova and killed a large number of its citizens.

The city quickly recovered as newcomers continued to arrive, and Christianity had gained a firm foothold in the city by no later than the second century.

SEVILLE or HISPALIS. Population: 40,000. Originally, this was a Phoenician city valued for its minerals, especially iron, which could be shipped downriver to the coast. The actual site of Seville seems to have moved around a bit as the city went through successive foundings. For a time, Seville was a Carthaginian city. Then came the Punic Wars, and Seville became Roman in 206 BCE when Scipio Africanus defeated the Carthaginians in the Battle of Ilipa Magna, fought about eight miles to the north. Scipio then settled a number of his veterans here and the city boomed, becoming famous for its many porticoed streets and attractive amphitheater with the capacity to seat 25,000. In 44 BCE Julius Caesar granted Seville the highly sought status of a colony,95 which later prompted the erroneous tradition that he was founder of the city. Two emperors, Trajan and Hadrian, were born in Seville. Christianity came sometime in the third century, and shortly thereafter Justa and Rufina achieved martyrdom for refusing to bow to an image of the local god Salambó.

Britannia

And finally, across the channel to Britannia.

LONDON or LONDINIUM. Population: 30,000. Supposedly, Julius Caesar imposed Roman rule on a collection of ‘semi-savage’ British tribes. In truth, these ‘barbarians’ were sufficiently civilized to use chariots against the legions. Seventeen years after the conquest, Queen Boudicca, head of a British tribe, led a rebellion during which London was sacked and burned. Eventually Hadrian had to build a great wall across the country to hold off rebels from northern strongholds. Still, Roman Britain endured for five centuries, during which London was its commercial and political capital.

Keep in mind, however, that while London technically was a port, it was effectively limited to cross-channel shipping. Except for the last twenty miles or so, the trip to London from Rome was a very long journey by land. Being so remote, London had no early Diasporan community and played virtually no role in church history until perhaps the third century. Later, of course, both British and Irish monks sustained extensive missions to the continent.

Conclusion

Map 2-1 shows all thirty-one cities having a population of 30,000 or more that were part of the Roman Empire in 100 CE. The map shows far more clearly than can be put into words that the urbanites were clustered in the East.

Despite the fact that about 95 percent of its population lived on farms or in tiny rural villages, Rome was an urban empire.96 As Wayne Meeks explained, “[T]he cities were where the power was…[and] where changes could occur.”97 The rural “population hovered so barely above subsistence level that no one dared risk change.”98 Thus it was that the overwhelming majority of early Christians were urbanites. Some of these urban Christians lived in cities and towns too small to be included in this set of the thirty-one largest. However, considering that the total urban population of the empire was about three million,99 the fact that the total population of these thirty-one cities was approximately two million suggests that they housed about two-thirds of the Greco-Romans who lived in towns and cities and probably about the same proportion of all urban Christians. The point is that the focus on the larger cities does not greatly distort our ‘slice’ of early Christian progress—most of it occurred here.

As is obvious, these cities differed in many ways. Had they not, they would be useless for analysis—all the important indicators being invariant. For it is the differences that matter: Why did only some cities attract Jewish settlements? Why didn’t they all welcome Isis? Why did some quickly embrace Christianity while others held out for several centuries? These sorts of questions underlie the entire enterprise. To proceed requires clear definitions and plausible measurements, and the place to start is with the primary concept of all early church history: Christianization.

MAP 2-1. All Greco-Roman Cities Having a Population of 30,000 or More

BAPTISM OF CHRIST. Some would say that Christianity began at this moment when John the Baptist baptized Jesus (as depicted by Joachim Patnir, ca. 1515).