THESE DAYS Gnosticism is the center of much interest, confusion, and faulty analysis. The term has long been applied to a number of esoteric ancient manuscripts, some of which claim to reveal a secret Christianity that is very different from the faith that appears in the New Testament. In addition, a variety of dissident religious movements, the first dating from as early as the second century, also have often been referred to as Gnostic.

I will take up both these aspects of Gnosticism in this chapter. First and foremost, however, I will examine the proposal made by Michael Allen Williams in the subtitle of his remarkable study Rethinking “Gnosticism”: An Argument for Dismantling a Dubious Category. As Williams so carefully documented, when the many manuscripts and movements usually categorized as Gnosticism are examined closely, various clusters of characteristics can be identified, but the only element common to all is that each is remarkably heretical, which is how they were quite properly judged by their contemporaries—not just “one heresy but a swarming ant-heap of heresies,” as the distinguished Simone Pétrement explained.1

Purely as a matter of faith, one is free to prefer Gnostic interpretations and to avow that they give us access to secret knowledge concerning a more authentic Christianity, as several popular authors recently have done.2 But one is not free to claim that the early church fathers rejected these writings for nefarious reasons. The conflicts between many of these manuscripts and the New Testament are so monumental that no thinking person could embrace both. Consider that some Gnostic ‘scriptures’ equate the Jewish God with Satan! Should those who defended conventional Christian teachings stand condemned of bigotry for not siding with such views? In addition, many of the Gnostic scriptures are obvious forgeries, easily recognized as such by the early church fathers, just as they ought to be today,3 in that whoever wrote them tried to deceive readers into believing they were the work of famous figures of first-generation Christianity—Peter, James, Mary Magdalene, Pilate, or Thomas, for example—or someone claiming extraordinary status, such as being the twin brother of Christ.

Whether the Gnostic teachers were ‘right’ or ‘wrong,’ that they were heretics vis-à-vis conventional Christianity cannot be disputed. Hence, the major portion of this chapter is devoted to heresies, and readers should imagine single quotation marks around the terms ‘Gnostic’ and ‘Gnosticism’ to indicate that they are being used very provisionally. However, by the end of the chapter, after we have empirically explored variations among these many heresies, it will become clear that there is a coherent subset of cases that deserves a collective identification.

This chapter begins by assessing Gnosticism as a category and then deals with a common confusion among manuscripts, schools, and movements. Many Gnostic manuscripts have been treated at various times in history, including the present, as if they had inspired social movements. But in many instances no trace of any such movement exists, and the most likely interpretation is that the manuscript was written by someone having few if any followers—so few, in fact, that we haven’t the slightest idea of who wrote the manuscript, when, or where. In other instances, prominent Gnostic writers are known to have gathered only small ‘schools’ of devotees, some of which met in secret and none of which bore any resemblance to even a small popular movement. After we have quantified a set of such schools, we will test several significant hypotheses concerning them. Then we will shift our attention to heretical movements that did attract popular support: Marcionism, Valentinianism, Montanism, and Manichaeism. These too we will quantify in terms of where each attracted supporters in order to test a variety of hypotheses concerning each, paying particular attention to correlations among heretical movements.

Gnosticism: A Dubious Category?

The word Gnosticism comes from a Greek word meaning “one who knows,” and what such a person knows is called gn–osis,4 which “does not refer to understanding of truths about the human and natural world that can be reached through reason. It refers to ‘revealed knowledge’ available only to those who have received secret teachings of a heavenly revealer.”5

The term Gnostic was applied by Irenaeus about 180 CE to the writings and followers of Valentinus.6 Several years later, Tertullian applied the word to groups other than the Valentinians.7 The name came into more frequent use by scholars during the eighteenth century, slowly gaining acceptance, and it has enjoyed great popularity since an international colloquium on Gnosticism was held in Messina, Italy, in 1966. In their “Final Document” members of the colloquium formally defined the term Gnosticism as claims to “knowledge of the divine mysteries reserved for an elite.”8 Many of the writers and groups taken to be Gnostic did “understand themselves to be the elite ‘chosen people’ who, in distinction from the ‘worldly-minded,’ were able to perceive” sophisticated matters and were in accord with the “goal of gnostic teaching…that with the help of insight (gn–osis), the elect could be freed from the fetters of this world.”9 This particular form of Gnosticism resembled what are known today as initiation cults.10 But not all putative Gnosticism involved secret elites; some inspired mass movements. So, knowing that secret elitism was not a criterion sufficient to embrace the full body of writings and organizations they wished to call Gnostic, the colloquium added many features to their definition and in doing so made it progressively less useful.

The stimulus for this international gathering of scholars was the discovery at Nag Hammadi in Egypt in 1945 of fifty-three fourth-century-CE manuscripts (forty-eight of them different). This trove of ancient texts had been carefully buried in a large earthenware jar. In all there were thirteen volumes bound in red leather, each volume containing multiple manuscripts. Some of these have no “Christian character whatever, a point established by the presence of part of Plato’s Republic.”11 However, at least forty of these manuscripts were subsequently labeled as Gnostic, many of them being complete copies of works known previously only by name. Others had been known only by excerpts included in attacks on them by early Christian opponents, beginning with Irenaeus, Bishop of Lyon, whose Adversus haereses (Against Heresies) appeared in about 180 CE. Perhaps surprisingly, when these actual Gnostic texts were compared with the synopses and excerpts included in the writings of their conventional opponents, they were in remarkably close accord. Jean Doresse, one of the earliest to study the manuscripts found at Nag Hammadi, noted that comparisons of the actual text of the Secret Book of John with excerpts quoted by Irenaeus show that the good bishop followed the Gnostic text essentially “word for word.”12 This came as a very great surprise to most modern scholars, who had made it an article of faith that, of course, the church fathers had greatly misrepresented the ‘heretics,’ the better to discredit them. Instead, the church fathers had quoted them accurately, perhaps because they thought that “the views they were quoting were so contorted and ludicrous that the heretics were best condemned out of their own mouths.”13 Even so, the charge that the early church fathers greatly distorted the Gnostic texts lives on among their modern advocates. Marvin Meyer, for example, wrote in 2005 that their “accounts are biased and apparently distort many features of the gnostic religion.”14

By the time of the conference at Messina, these newly found materials had all been translated from Coptic and published in several modern Western languages, and in 1977 splendid English translations of the entire set were published under the editorship of James M. Robinson. Aside from being at substantial variance with the New Testament, these Gnostic works contain no themes or theses common to all. But certain elements are common to many, and we turn to those now.

Chief among the common themes is the idea of two gods, taken from Greek philosophy and carried to a radical extreme: a supreme good God who is very remote from the world, and a less powerful, evil Demiurge who created a completely worthless, evil world and who torments humanity.

Radical Dualism

As discussed in Chapter 4, except for monotheisms based on impersonal divine essences such as the Tao, all monotheisms are dualistic to some extent. This provides them with a solution to the problem of evil. If there is but one God, creator of everything and in charge of everything, why is there evil in the world? It follows that God, being the source of all things, is the source of all evil. What is to be made of such a being? The traditional Jewish, Christian, and Muslim solution to this thorny issue is to accept the existence of lesser supernatural beings who are the source of evil—who for various reasons and within various limits brought evil into the world. Satan and his demons are fallen angels who tempt humans to sin, but whose powers are puny compared with God; and therefore these fallen ones will eventually be defeated—in God’s good time.

For many Gnostic writers this was much too accommodating and failed to acknowledge that the world is evil to the core, that nothing in this life has any redeeming features. Influenced by Plato’s ideas about a remote supreme God who allowed a lesser god, the Demiurge, to create the world, some Gnostic writers spun out extremely dualistic accounts of the universe.

To summarize these views, the best source to consult is The Secret Book According to John (or The Apocryphon of John). In part this is because this Gnostic manuscript has survived in four copies (three of them from Nag Hammadi), which suggests that it was widely circulated. Moreover, because it is a complete document dating from around the fourth century, no one can dismiss it as a biased summary written by the conventional Christian enemies of Gnosticism. Finally, to the extent that there is a core Gnostic work, this is it—Michel Tardieu has called it “the gnostic Bible par excellence.”15

The manuscript identifies its author as the Apostle John, based on a postresurrection appearance by Christ, who instructed John about “the mysteries which are hidden in silence.”16 The revelation begins with the supreme mystery, the nature of God, who is identified as the “invisible spirit,” so “superior to deity” that it “is not fitting to think of it as divine.” Eventually, when God thought about his own perfection, that resulted in the existence of an independent entity known as First Thought, or Barbelo. Barbelo also is the Mother and hence the consort of God the Father, and this resulted in a self-generated Child. This trinity then produced a whole entourage of divine entities known as “aeons.” For some immense time all went well: “[T]he scene portrayed in this divine realm is one of complete order, peace, and reverence.”17 But the calm didn’t last. One of the divine entities went bad—the one named Wisdom. Without permission from God, Wisdom did her own creative imagining, bringing forth a child. It was a grotesque monster: “serpentine, with a lion’s face, and with its eyes gleaming like flashes of lightning.” To hide her folly, Wisdom “surrounded it with a luminous cloud. And she put a throne in the midst of the cloud, so that no being might see it except for the holy spirit…and she called its name Ialtabaoth.”

Now things get interesting. Ialtabaoth doesn’t merely look like a monster; he is one. “Completely self-willed, he steals spiritual power from his mother and runs off and sets about creating a world he can control as he pleases.”18 He is none other than the God of Genesis, who creates “a gang of angelic henchmen, rulers (“archons”) who are to help him control the realm of darkness, and he goes about setting up his rule in the classic style of a petty tyrant,” as Michael Williams so aptly summarized.19 Having created the earth and given it inhabitants, Ialtabaoth began to assert, “For my part, I am a jealous God. And there is no other god apart from me.” The book now relates a revised version of the whole Adam and Eve, Garden of Eden saga. Once having thrown Adam and Eve out of the Garden, Ialtabaoth instilled a desire for sexual intercourse in humans and then seduced Eve to produce Cain and Abel, the former with the face of a bear, the latter with that of a cat. Adam then fathered Seth, who, unlike Cain and Abel, possessed the spirit of God. Seth and his descendents were regarded as an affront by Ialtabaoth and his henchmen, so he tried to kill them all with the flood. Having been thwarted by Noah, next Ialtabaoth sent evil angels disguised as men; they took women for their brides and generated a polluted humankind.

At this point the secret book offers a “poem of deliverance,” wherein Jesus explains that he came to free humanity from the chains of Ialtabaoth. However, Jesus does not end his revelations by encouraging John to go forth and convert the world. Not at all: “For my part, I have told you all things, so that you might write them down and transmit them secretly to those who are like you in spirit.”

The core message of The Secret Book of John and of many other Gnostic teachings is that the earth is held in thrall by an evil God. But since many other Gnostic teachings propose no such thing, it fails as a definitional criterion.

Anti-Judaism

According to many Gnostic texts, the evil God is the God of the Jews, and his Chosen People were so designated for good reason—in that they worship and proselytize on behalf of this evil creature. Although some Gnostic texts do not condemn the God of the Old Testament as evil and are very favorable to Jews,20 most of them display what Hans Jonas described as “a kind of metaphysical anti-Semitism.”21 They “portray the Old Testament God as vain, ignorant, envious, and jealous—a malicious Creator who uses every means at his disposal to keep humanity from attaining true perfection.”22

In The Testimony of Truth, another of the manuscripts recovered at Nag Hammadi, a section begins by recounting the story of Adam and Eve eating from the tree of knowledge as told in Genesis. Having reached the point where God found out that Adam and Eve had eaten of the tree, God said:

“Behold, Adam has become like one of us, knowing evil from good.” Then he said, “Let us cast him out of Paradise lest he take from the tree of life and eat and live forever.” But of what sort is this God? First (he) maliciously refused Adam from eating of the tree of knowledge. And secondly he said, “Adam, where are you?” [This] God does not have foreknowledge; (otherwise) would he not know from the beginning? (And) afterwards he said, “Let us cast him (out) of this place, lest he eat of the tree of life and live forever.” Surely he has shown himself to be a malicious grudger.

At this point the Testimony shifts from an exclusive focus on the God of the Old Testament to those who worship him.

For great is the blindness of those who read, and they do not know him [ for what he is]. And he said, “I am a jealous God; I will bring the sins of the fathers upon the children until three (and) four generations.” And he said, “I will make their heart thick, and I will cause their mind to become blind, that they might not know nor comprehend the things that are said.” But these things he said to those who believe in him (and) serve him!

These passages are not exceptional. Many Gnostic texts abound in antagonism toward the God of the Jews—and some do not.

Sexuality

Christianity may be somewhat ambivalent about sexual expression, but, being very pro-natal, it values marital sexuality. Not only did Paul admit, “It is better to marry than to burn,” but he also counseled married couples not to practice chastity, but to fully extend to one another their “conjugal rights.”23 In contrast with many Gnostic texts, Paul seems a virtual libertine.24

For most early heretics, sexual intercourse was to be absolutely avoided: it provided the wicked angels (archons) with the means to continue to mislead and torment humans, in that sex was assumed to be an act of utter defilement. In The Sophia (or Wisdom) of Jesus Christ (found at Nag Hammadi), following his resurrection the Savior appears to “his twelve disciples and seven women [who] continued to be his followers” and informed them that, among other things, they can be released from the grip of forgetfulness concerning wisdom if they do not engage in “the unclean rubbing” of sexual intercourse.25 The Paraphrase of Shem condemns intercourse as “defiled rubbing.”26 The Gospel of Philip, another work recovered at Nag Hammadi, gets right to the point: “There are two trees growing in paradise. One bears animals, the other bears men. Adam ate from the tree which bore animals. He became an animal and he brought forth animals.”27 Or, as it says in The Book of Thomas:

Woe unto you who love the sexual intercourse that belongs to femininity and its foul cohabitation.

And woe unto you who are gripped by the authorities of your bodies; for they will afflict you.

Woe unto you who are gripped by the agencies of wicked demons.

Consequently, many heretical texts advocate absolute celibacy and rate it as especially virtuous to not bring children into the world.

This persistent element in Gnostic writings, especially as reflected in the commitment to radical abstinence by major heretical movements such as the Marcionists and Manichaeians, may have been a major factor in the failure of such movements. Although the conventional Christian church accorded special sanctity to those who observed celibacy, it fully embraced those who lived in marital bliss. Nock put this well: “Christianity did indeed go a long way with those in whose eyes sexual life was unclean; it gave satisfaction to the many who were fascinated by asceticism, but it repressed those elements within itself which overstressed that point of view, and it never set its face against the compatibility of normal life with the full practice of religion.”28

Of course, some heretics also accepted sexuality, at least within marriage. Moreover, a few seem to have gone far in the other direction, taking the view that their access to secret wisdom liberated them from all need for sexual restraint. As Robert M. Grant summed up: “Gnostic ethics ran the gamut from compulsive promiscuity to extreme asceticism.”29 Several somewhat obscure Gnostic groups believed that the sexual morality of the Old Testament was but a control mechanism by which the archons enslaved humanity, and those groups therefore advocated unrestricted sexuality as a means of bursting these evil bonds. It was charged against the Valentinians that they approved of adultery. In the words of Bishop Irenaeus:

Wherefore also it comes to pass, that the “most perfect” among them [Valentinians] addict themselves without fear to all those kinds of forbidden deeds….[Some] yield themselves up to the lusts of the flesh with the utmost greediness, maintaining that carnal things should be allowed to the carnal nature, while spiritual things are provided for the spiritual. Some of them, moreover, are in the habit of defiling those women who have been taught the above doctrine, as has frequently been confessed by those women who have been led astray by certain of them, on their returning to the Church of God, and acknowledging this along with the rest of their errors. Others…seduce [women] from their husbands…. [Others] pretend to live in all modesty with [women] as with sisters, [but] have in course of time been revealed in their true colors, when the sister has been found with child by her pretended brother.

Two centuries later, Epiphanius of Salamis claimed firsthand knowledge of libertine practices among members of a Gnostic sect, stating that as a young man he had been seduced by members of this group during a ritualized orgy and that “they curse anyone who is abstinent.”30

Most of those Gnostics who denounced sexuality did so as means to thwart the evil Demiurge, not on grounds of right and wrong. The concept of virtue is incompatible with the idea that the world and all that is in it is totally and inherently evil, being the creation of a diabolical deity. On these grounds, the great third-century Neoplatonist philosopher Plotinus condemned the Gnostic schools in his famous Enneads (2.9.15): “Their doctrine[,]…by blaming the Lord of providence and providence itself, holds in contempt all…virtue…[and] puts temperance to ridicule, so that nothing good may be discovered in this world…. It is revealing that they conduct no inquiry at all about virtue and that the treatment of such things is wholly absent from their teachings…. Without true virtue, God remains an empty word.”

Of course, abstinence was not the only plausible response to the denial of virtue; on logical grounds alone, libertinism was an equally valid conclusion. As for the truth of charges that some Gnostics were libertines, one should note the many instances in which modern elitist, esoteric groups have opted for promiscuity—for example, the many Hermetic and Wiccan groups.

Heresy

Elaine Pagels stresses that the Gnostic writers “did not regard themselves as ‘heretics.’”31 Of course not. But the issue of heresy is hardly a matter of self-designation. Let us assume that these writers (including the forgers) sincerely believed that they possessed the truth and that the conventional Christians had it all wrong, while the conventional Christians were equally sure that theirs was the true Christianity. Within the confines of faith, the charge of heresy can be resolved objectively only on the basis of which side more accurately transmitted the original teachings of Jesus. That decision must come down to sources. The New Testament gospels claim to be based on the recollections of those who knew Jesus and heard his words. The four gospel narratives abound in correct historical and geographical details, and nearly everything takes place on this earth and involves people who very probably existed. As Philip Jenkins put it: “[O]rthodox Christians at least believed that Jesus had lived and died in a real historical setting, and that it was possible to describe these events in objective terms. For Gnostics, by contrast, Christ was not so much a historical personage as a reality within the believer.”32 Hence, the typical Gnostic work, like The Secret Book of John, gives its origins as the author’s visions and mystical revelations, which are set in another reality and include almost no historical or geographical content. As Pheme Perkins explained, “Gnostics reject gods and religious traditions that are tied to this cosmos in any way at all! Thus, Gnostic mythology often seems devoid of ties to place or time.”33 In this way, Gnostic scriptures far more resemble pagan mythology than the New Testament, in that ‘events’ so often occur in an immaterial, otherworldly, ‘enchanted’ setting. In fact, many Gnostic works are an exotic amalgam of paganism, Greek philosophy, Christianity, and Judaism.

In keeping with their intuitive methods and their lack of worldly referents, various Gnostic writers stressed that originality was the test of true inspiration. Irenaeus put it wryly: “[E]very one of them generates something new, day by day, according to his ability; for no one is deemed ‘perfect’ who does not develop among them some mighty fictions.”34 Elaine Pagels has taken a rather more favorable view of the matter: “Like circles of artists today, Gnostics considered original creative invention to be the mark of anyone who becomes spiritually alive. Each one, like students of a painter or writer, expected to express his own perceptions by revising and transforming what he was taught. Whoever merely repeated his teacher’s words was considered immature.”35 Pagels went on to contrast this ‘creative spirituality’ with what she seemed to regard as the rather constipated orthodoxy of Bishop Irenaeus, who thought it both bizarre and wicked to propose that “mighty fictions” were a superior guide to history and truth.

Had the Gnostics prevailed, they presumably would be viewed today rather more in the manner that Pagels and other ‘Ivy League’ Gnostics would wish, assuming that such a thing as Christianity still existed. But the Gnostics did not prevail, because they did not present nearly so plausible a faith, nor did they seem to understand how to create sturdy organizations. Instead, most of them did and taught their own ‘thing.’ To sum up, the Gnostic gospels were rejected for good reason: they constitute idiosyncratic, often lurid personal visions reported by scholarly mystics, ambitious pretenders, and various outsiders who found their life’s calling in dissent. Whatever else might be said about them, surely they were heretics. As N. T. Wright put it, they “represent…a form of spirituality which, while still claiming the name of Jesus, has left behind the very things that made Jesus who he was, and that made the early Christians what they were.”36

Even so, these writers and groups weren’t Gnostics, unless we deprive that word of any useful meaning. Some were radical dualists; some weren’t. Some were extremely anti-Jewish; some were very pro-Jewish. Some were remarkably ascetic; some were libertine. Some regarded their beliefs as arcane secrets to be revealed only slowly to a small elite initiated into the inner circle; some led mass movements. Because of these gross inconsistencies (and many others),37 it seems wise to shelve the term Gnostic except when dealing with traditional discussions of these movements and materials. Instead, let us use the one concept that fits them all—“early heresies”—as we look at early heretical manuscripts, schools, and major movements.

Early Heretical Manuscripts

It too often is assumed that manuscripts imply social movements. Thus, the existence of a Gnostic manuscript often is taken to mean that it served as the gospel of a heretical movement. But that simply doesn’t follow. Today’s New Age bookstores are filled with publications that represent nothing more than one writer’s opinions. The same seems plausible in the case of many of the surviving heretical manuscripts. They are works entirely without provenance or context. We don’t know who wrote them, where, or (within several centuries) when. Nor is there the slightest surviving hint that most of these strange works were associated with a social movement—there is no necessary reason even to suppose that it was an organized heretical group that buried the manuscripts at Nag Hammadi. Consequently, these works can be studied only as literature. It is not idle to examine the ideas in these works or to compare them to other works of the era. But even the existence of similarities does not establish that any one of them influenced other works; it could as well mean that the author of the work in question was influenced by others. In the end, it is impossible even to say who read many of these anonymous manuscripts, except that the works quoted by Irenaeus, Hippolytus, and Epiphanius obviously had circulated sufficiently to arouse opposition, and the books buried at Nag Hammadi presumably had been read by someone.

Of course, some surviving heretical manuscripts were written by known historical figures. While some of these people also led major heretical movements, others modeled themselves on classical philosophers and were content to found a ‘school’ consisting of a small group of disciples, among whom the “authoritative teaching was transmitted, interpreted, and kept secret. There must have been regular meetings of some sort.”38

Early Heretical Schools

Very little is known about the “School of St. Thomas”39 other than that it was probably located in Edessa. Beyond that, what survives are manuscripts that clearly were not written by their central character: St. Didymus Jude Thomas, Apostle of the East, and self-proclaimed twin brother of Jesus. The Thomas literature lacks some ‘typical’ elements of Gnosticism. For example, although these works stress that the spiritual world is within the individual, they do not posit an inferior, evil creator-deity. However, most of the Thomas works appear to be very strange fantasies, although some interpreters propose that there is profound meaning concealed “behind a figurative fairy tale or folktale.”40 However, the most famous of the Thomas works, The Gospel According to Thomas, has no story at all. It consists entirely of 114 sayings attributed to Jesus, beginning:

1) These are the obscure (or hidden) sayings that the living Jesus uttered and which Didymus Jude Thomas [his twin] wrote down. And he said, “Whoever finds meaning in these sayings will not taste death.”41

Some of the sayings appear in the New Testament. Some do not. Some seem to be of Gnostic origin. Some are remarkably obscure. Some seem quite inferior, straining for profundity, compared with those of New Testament origin. Since the entire work can be printed on a few pages, it seems remarkable that Elaine Pagels would have written a book-length celebration of the liberating ideas she finds in this “secret gospel” without providing her readers with all 114 sayings, even if only in a brief appendix. In fact, she very seldom quoted from Thomas—perhaps so that she could emphasize the joys of seekerhood and mock the constraints of creeds without having to interpret ‘sayings’ such as these:

As to freedom from constraints:

27) Jesus said: “If you do not abstain from the world you will not find the kingdom. If you do not make the sabbath a sabbath you will not behold the father.”

As to elitism:

49) Jesus said: “Blessed are those who are solitary and superior, for you will find the kingdom; for since you come from it you shall return to it.”

As to feminism:

114) Simon Peter said to them: “Mary should leave us, for females are not worthy of life.” Jesus said, “See, I am going to attract her to make her male so that she too might become a living spirit that resembles you males. For every female (element) that makes itself male will enter the kingdom of heaven.”

In fairness, Pagels did include this last saying (114) in her earlier (1979) book on the Gnostic gospels.

Those most favorable to the Gnostics assign a very early date to Thomas, but most historians date it from the middle to late second century, when the New Testament canon was already formed. This later date is encouraged by the fact that no mention is made of it by Irenaeus; the first known reference to it is by Hippolytus, who wrote between 222 and 235 CE. In addition to probably having begun in Edessa, the St. Thomas school seems to have stimulated several ‘branch campuses,’ in Alexandria, Memphis, and Oxyrhynchus.42

Historians agree that Saturninus (often Satornil or Satorninos) was a real heretical teacher who founded a school in Antioch around the end of the first century. But that’s all that is known about him. As to his views, no manuscript has survived, but his teachings, as summarized by Irenaeus, included all of the ‘classic’ elements of Gnosticism. To quote from Irenaeus:

Saturninus…set forth one father unknown to all, who made angels, archangels, powers, and potentates. The world, again, and all things therein, were made by a certain company of seven angels. Man, too, was the workmanship of angels…. He [Saturninus] also laid it down as a truth, that the Saviour was without birth, without body…that the God of the Jews was one of the angels; and, on this account, because all the powers wished to annihilate his father, Christ came to destroy the God of the Jews…. They [the followers of Saturninus] declare also, that marriage and generation are from Satan…. Saturninus represents as being himself an angel, the enemy of the creators of the world, but especially of the God of the Jews.

Since these all are frequently expressed Gnostic tenets supported by actual surviving texts, there is no reason to doubt the accuracy of Irenaeus’s summary. If only the good bishop had also included some biographical information on Saturninus.

Slightly more is know about Basilides, who founded a very influential heretical school in Alexandria during the second century. It was he who ‘discovered’ that there had been no crucifixion or resurrection of Jesus. Again Irenaeus:

[Basilides claimed that Jesus] did not himself suffer death, but Simon, a certain man of Cyrene, being compelled, bore the cross in his stead; so that the latter being transfigured by him, that he might be thought to be Jesus, was crucified through ignorance and error, while Jesus himself received the form of Simon, and, standing by, laughed at him.

No one now disputes Irenaeus’s summary, although many seem to prefer Basilides’ versions to those in the New Testament. As to influence, Basilides’ school in Alexandria “was apparently still active in the mid–fourth century.”43

Valentinus opened a heretical school in Alexandria before moving it to Rome. Born in the Nile Delta about the year 100 CE, Valentinus was educated in Alexandria, quite possibly as a student of Basilides.44 He is believed also to have been greatly influenced by the writings of the Hellenized Jewish philosopher Philo and to “have been exposed to the mystical Thomas tradition that originated in Mesopotamia and was popular in Egypt in Valentinus’s time.”45 He moved to Rome around 140 CE, where he soon became a serious candidate for the office of bishop of Rome (before being expelled from the Christian church for heresy).

Valentinus was very much the academic intellectual, and his “movement had the character of a philosophical school, or network of schools, rather than a distinct religious sect.” What he and his students aspired to achieve was “to raise Christian theology to the level of pagan philosophical studies”; in fact, “the very purpose of the school was speculation.” They justified their speculations as based “on the authority of a secretly transmitted academic tradition, whose origin they traced back to St. Paul.”46

What Valentinus actually taught is open to some dispute, since most of the views attributed to him were actually expressed by his outstanding student Ptolemy. There is no reason to suppose that the student departed greatly from his master, however, and therefore it seems reasonable to associate Valentinus with at least some of the radical speculations presented in Ptolemy’s own teachings. Consequently, many scholars “see in Valentinus’ teachings the apex of gnosticism, the greatest and most influential of the gnostic schools.”47 Not only do many later Gnostic texts clearly reveal Valentinian influences, but his students carried on his work by establishing several branch campuses (one in Carthage) and by organizing a major heretical movement, as will be seen. What made Valentinus so successful, and such a threat to conventional Christianity, was his effort to reconcile the New Testament with classic elements of Gnosticism by applying “a peculiar allegorical interpretation of those commonly accepted texts,”48 thereby discovering hidden and deeper levels of meaning consistent with those revealed to Gnostic visionaries. Put another way, what Valentinus and his students did was ‘discover’ proofs in support of Gnostic interpretations hidden in the conventional gospels.

These four heretical schools, then—the schools of Valentinus, Basilides, Saturninus, and St. Thomas—were the best known. In addition, both Cerdo and Heracleon probably had schools in Rome, as did Marcus in Byzantium.49 Several others, including Isidore, Justin, Concessus, and Marcarius,50 may have led schools too, but we know nothing of these ‘writers’ except their names. Some scholars place Gnostics in Corinth on the basis of passages in 1 and 2 Corinthians,51 and this may be so. But even if Paul’s local opposition in Corinth did come from some extremely early Gnostics, there is nothing to suggest that they constituted a ‘school.’

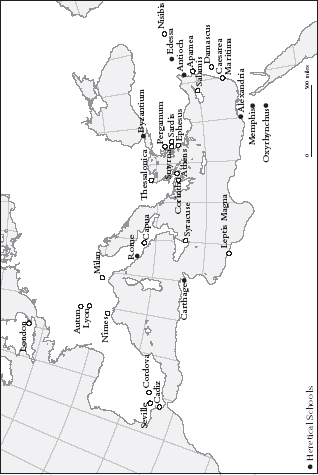

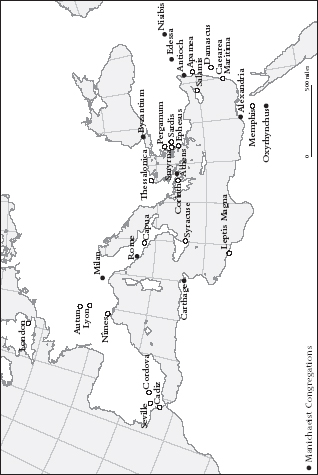

Map 6-1 shows cities thought to have had heretical schools prior to 300 CE. By scoring all eight cities having a school as one and the others as zero, we transform the location of heretical schools into a variable.

Travel

We have seen that Christianity and Isiacism spread across regular trade and travel routes, gaining supporters in port cities sooner than elsewhere. But Robert M. Grant has argued that the reason early heretical schools exhibited such “remarkable diversities in doctrine” is because they did not spread nearly so much as they were independently constructed by various ‘teachers’ who shared only “a common Gnostic attitude.”52 This leads to:

HYPOTHESIS 6-1: Port cities were no more likely than inland cities to have heretical schools.

The data show that Grant was quite right (Table 6-1). There is no relationship between ports and heretical schools—as with other intellectual pursuits, heretical scholarship was a sedentary activity.

City-Size

Heretical schools surely fit Claude Fischer’s definition of a deviant subculture, meaning that his subcultural theory of urbanism would apply. Moreover, since schools did not travel, their existence depended upon rounding up a sufficient number of local students. Consequently:

HYPOTHESIS 6-2: Larger cities were more likely than smaller cities to have heretical schools.

This hypothesis is strongly supported: nearly two-thirds of the larger cities did shelter heretical schools, as compared with only 13 percent of the smaller cities (Table 6-2). However, this relationship probably isn’t just about population size per se. The larger cities also tended to be the cultural centers of their region, and intellectuals always have congregated in such places. The heretical teachers were no exception.

Jewish Roots?

We turn now to one of the great controversies concerning Gnosticism. Until the start of the twentieth century, scholars were content to regard Gnosticism as a Christian heresy—in keeping with the judgments of the early church fathers. Then, in keeping with the impulse to novelty prompted by the fact that the rapid road to academic status is innovation, Moritz Friedlander traced the origins of Gnosticism to Jewish roots and claimed that Christianity and Gnosticism were parallel offshoots of first-century Hellenic Judaism.53 This view soon gained a great deal of support, culminating in Birger Pearson’s assertion: “Gnosticism is not, in its origins, a ‘Christian’ heresy, but…it is in fact a ‘Jewish’ heresy.”54 As for the intense anti-Judaism of much of this literature, it was said to reflect the antagonism of bitterly rebellious ex-Jews against the faith of their fathers.

But it is not only its widespread “metaphysical anti-Semitism” that gives pause to accepting the claim that Gnosticism originated in Judaism. There also is the fact that, with only several exceptions, the Gnostic writings are greatly concerned with new stories about and new interpretations of Christ. Other than giving great attention to Genesis, most Gnostic books focus on New Testament matters: about what Jesus really said, his true nature, and how his mission will be accomplished, as revealed to various figures claiming major Christian status: John, Peter, Mary, Thomas, Mark, James, Matthew, and others. I suppose that if Gnosticism were primarily Jewish, much more attention would have been devoted to Old Testament matters and many of the manuscripts would have been attributed to various prophets. Of course, Pearson was careful to say only that Gnosticism was of Jewish origins. This leaves room for its Jewish authors to have been Christian converts. In that case, all Pearson really said is that Gnosticism originated with Jewish Christians. But so did Christianity! If one can spot Jewish elements in Gnostic writings, so what? The gospels contain at least as much Judaism! And for all the concern over the anti-Jewish passages of the New Testament,55 they are mild and infrequent compared with many Gnostic gospels.

For all these reasons, a reaction has been building up against the notion that Gnosticism is Jewish rather than Christian. The celebrated French historian Simone Pétrement delivered a major blow to that notion in 1990, with the publication of her book A Separate God: The Christian Origins of Gnosticism. This is just the sort of never-ending dispute that is suitable for a quantitative approach to early church history. Let’s use the data to test the following:

HYPOTHESIS 6-3: Heretical schools did not cluster in cities having large Diasporan Jewish communities.

This hypothesis is very strongly supported: there is no significant correlation between the Diaspora and Gnostic schools (Table 6-3). Of course, this does not prove that Gnosticism wasn’t mainly a Jewish enterprise, but it would seem to make it rather less probable: if the Gnostics were intellectual Jewish rebels, they must have left home.

Churches and Schools

Finally, there is no particular reason to suppose that Gnostic schools were more apt to be established in cities that were in the forefront of Christianization. For one thing, the presence of vigorous local Christian groups may have been a deterrent when heretical teachers were deciding where to set up a school. Such teachers may have considered it far more important to locate in a community where religious novelty and diversity thrived.

And that leads to an additional consideration, one that mostly has been ignored by recent participants in this dispute concerning the origins of Gnosticism. Fully in accord with von Harnack’s claim that Gnosticism was “the acute secularizing or hellenising of Christianity,”56 a strong case can be made that paganism and Greek philosophy played an even more important role in Gnosticism than did either Judaism or Christianity—in other words, that many Gnostic works were pagan adaptations of the rapidly expanding Christian and Jewish monotheism. As noted in Chapter 5, many elements found in Genesis and in the Christ story were familiar pagan doctrines well before the birth of Jesus. In addition, the idea of a remote supreme God and a lesser divinity called the Demiurge does not derive from either Judaism or Christianity, but was prevalent in classical philosophy. (As noted earlier, Plato probably originated the Demiurge thesis.) In addition to these correspondences, consider how much more like paganism than either Judaism or Christianity is the relentlessly ‘mythical’ and a historical character of the Gnostic materials. A serious examination of the pagan roots of Gnosticism will be undertaken in the next chapter. Here it is sufficient to hypothesize that:

HYPOTHESIS 6-4: Heretical schools did not cluster in cities having an early Christian congregation.

The data confirm that, as hypothesized, Christianization is not significantly related to heretical schools (Table 6-4).

To sum up: in founding their schools, heretical teachers did not favor port cities, nor did they seek places abundant in either Jews or Christians. What they did was gravitate to the cultural centers which were, for the most part, the larger cities.

Major Heretical Movements

We now shift our attention from manuscripts and schools to more significant undertakings. Whatever can be deduced about the intentions of those who wrote the texts buried at Nag Hammadi, the leaders of major heretical movements aimed to supplant the conventional Christian church. As we characterize and analyze these movements, it will be useful to keep in mind just how tiny they must have been. Consider that during the first half of the second century, when “Marcionites could be found all over the empire,”57 there probably were no more than twenty to thirty thousand Christians of all varieties. How many of these were Marcionites is impossible to say, although many historians believe that they made up a very significant minority.58 Even if this is so, there never were all that many people involved in the movement—surely not more than ten thousand, and probably many fewer—although their numbers may have increased by the third century (given that Marcionite congregations still existed as late as the fifth century). In any event, Marcion was regarded as “the most formidable heretic of the second century CE.”59 His was also the earliest of the major heretical movements.

Marcionism

Marcion probably was born late in the first century in Sinope, a Black Sea port in Asia Minor; his father may have been the bishop of Sinope. There is some reason to believe that Marcion made a huge fortune in the shipping industry, but beyond that very little is known of his life and career. Some historians assume he must have become a bishop at some point before going to Rome, since no layman would have been permitted to debate theology with the church presbyters.60 The only date of probable reliability is that he was excommunicated in Rome in 144 CE. What is certain is that “Marcion was apparently the first Christian ever to set forth a ‘New Testament’—that is, a closed collection of Christian Scriptures.”61 His consisted only of Luke’s gospel (somewhat edited), ten letters of Paul (not including the Pastoral Epistles and Hebrews) and his own Antitheses, which has not survived but which was an elaborate statement of what Marcion believed to be the many contradictions between the Old Testament and what Jesus taught. Therefore, Marcion argued, if one were to fully embrace Christ, one must expel the Judaizers from Christianity—he included Peter, James, and John among those who had “diluted and distorted the true teaching of Jesus”62 to accommodate the Old Testament. Many historians of the early church agree that in defining his testament, Marcion made it necessary for the church fathers to be specific about what was and was not part of their official canon, thus creating the New Testament pretty much as we know it.

On purely theological grounds, Marcion’s position might have had considerable appeal. Clearly there was conflict between Jewish and Gentile Christians, and there always have been difficulties in harmonizing the New and Old Testaments. But Marcion was not content to promote a purely Pauline brand of Christianity. He demanded total celibacy, charging that the directive to be fruitful and multiply came from the God of the Jews. He also preached other forms of abstinence, declaring that it was sinful to enjoy food or drink; he even substituted water for wine in liturgical use. Consequently, what Marcion founded was not so much a mass movement as an ascetic ‘order’ for the laity.

There is some disagreement among scholars as to whether Marcion should be identified as a Gnostic. He was bitterly opposed to Judaism and dismissed the Jewish God as inferior and unjust, thereby seeming to echo the essential Gnostic idea of the evil Demiurge. But, as Hans Jonas explained, he did not pursue this point to the Gnostic conclusion: “[H]owever unsympathetically depicted, he [the Jewish God] is not the Prince of Darkness.”63 Nor did Marcion spin out a new Genesis: “[H]is teaching is entirely free of the mythological fantasy in which gnostic thought reveled: he does not speculate about the first beginnings; he does not multiply divine and semi-divine figures.”64 Instead, Marcion was content to catalogue the contradictions between Christianity, as he understood it, and the Old Testament. Moreover, within his limits he was an orthodox Christian who fully accepted Luke’s gospel and Paul’s teachings, without adding any esoteric touches. As von Harnack put it, Marcion “unequivocally confessed a Pauline Christianity.”65 Consequently, Marcion seems to have been somewhat optimistic about his chances when he took his proposals for a ‘purified’ Christianity to leaders of the Christian church in Rome. It was only after they rejected him, and excommunicated him when he refused to recant, that Marcion became a rebel—although he probably had attracted followers and founded congregations prior to visiting Rome.

Perhaps quantitative analysis can shed light on some of these matters.

Let’s look at Map 6-2, which draws primarily on von Harnack’s extensive study of Marcionism,66 supplemented by others.67 We see on the map that 13 of the 31 cities in the data set were determined to have harbored a Marcionite congregation.

First to be addressed is the question of whether Marcion was a Gnostic. On the basis of his teachings, there is no reason to suspect that Marcion was especially influenced by any of the heretical schools discussed above. Hence:

HYPOTHESIS 6-5: Marcionite congregations were not more common in cities having heretical schools.

The data reveal no significant difference between cities with a heretical school and those without as to having had a Marcionite congregation; thus the hypothesis is confirmed (Table 6-5). This finding supports those who contend that Marcion was not a Gnostic.

What seems far more important, however, is Marcion’s anti-Judaism. There are substantial grounds for assuming that this was not a purely intellectual matter, but that it reflected real antagonism between Jewish and Gentile Christians. In this regard, the Gospel of John, which is taken to be the latest of the four synoptic gospels and which probably was written not long before Marcion began his career, is notably more antagonistic toward Judaism than are the other three gospels. Unlike Marcion, John clearly accepts that the God of the Jews is the Father of Christ, but he quotes Jesus “time and again, that the Jews do not know God.”68

This was symptomatic of a worsening in relations between the two faiths, which by Marcion’s time was exacerbated by the Bar-Kokhba Revolt (132–135) in Palestine against the Romans—a revolt that Christians disavowed. But it seems probable that Jewish-Gentile conflicts within the Christian community played an even more important role. First of all, that Marcion could so easily be anathematized suggests that the fledgling church still was greatly influenced by Jewish Christians—the success Marcion had in recruiting followers suggests that his proposal to dismiss the Jewish heritage was popular among Gentile Christians. Indeed, the proposal to dispense with the Old Testament has been favorably reinterpreted by a series of modern scholars who hail Marcion as the first Protestant, “harking back to the pure message of Jesus and his Father.”69 Second, despite Paul’s ruling against Jewish Christians continuing to observe the Law, many clearly did continue to observe it, and it seems likely that they regarded Gentile Christians as somewhat inferior. In fact, there was a heretical form of Jewish Christianity whose members “wished to maintain their Jewish observances (circumcision, food laws, the Sabbath, etc.). Moreover, many of them, even though they venerated Christ, did not consider him absolutely divine or consubstantially united to the one God.”70

One can plausibly hypothesize, therefore, that the anti-Judaism of many early heresies was, as Pheme Perkins suggested, “formed by people who lived in close proximity to Judaism and in reaction against it.”71 That is, these attitudes were aroused by close contact and conflict, not by separation and unfamiliarity. Hence:

HYPOTHESIS 6-6: Marcionite congregations were more likely to arise in cities having large Diasporan Jewish communities than in those without.

This hypothesis is very strongly confirmed. Marcion gathered congregations more successfully in cities with large Jewish populations (89 percent)—cities where conflicts between Jews and Christians, and especially between Jewish and Gentile Christians, would have been maximized—in contrast with cities lacking Diasporan communities, only 27 percent of which had a Marcion congregation (Table 6-6). Indeed, the growth of Marcionism and the severe official church response to its teachings can be taken as additional evidence that Jewish conversion to Christianity, and hence Jewish influence within Christianity, lasted rather longer than has been recognized (see Chapter 5).

MAP 6-2. Marcionite Congregations

In addition, Marcionism proved not to be significantly related to Christianization, ports, or city-size (tables not shown).

Valentinianism

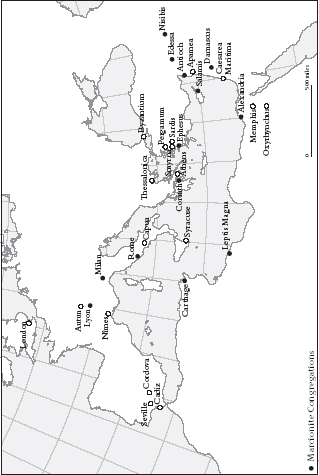

All historians classify Valentinus, unlike Marcion, as a ‘Gnostic’—indeed, perhaps the prototype thereof. They take the same view of the Valentinians, the heretical religious movement launched by his successors. Map 6-3 locates Valentinian congregations.72

In keeping with the traditional view of the Valentinians as Gnostics, it follows:

HYPOTHESIS 6-7: Valentinian congregations were more common in cities having heretical schools than in cities having none.

Seven out of eight cities with a heretical school had a Valentinian congregation, while only two of twenty-three cities without a school had a Valentinian congregation (Table 6-7). The correlations are huge and significant. This not only demonstrates that the Valentinians were in some sense Gnostics but also reinforces the finding that the Marcionists weren’t.

Not surprisingly, there was no significant correlation between Valentinianism and Marcionism, nor was Valentinianism correlated with Diasporan communities, Christianization, or ports. What about city-size?

HYPOTHESIS 6-8: Valentinian congregations were more common in larger cities than in smaller ones.

True! Seventy-five percent of the larger cities had a Valentinian congregation, compared with 13 percent of the smaller cities (Table 6-8).

Using regression analysis to inspect the impact of both city-size and heretical schools on Valentinianism (Regression 6-1), we discover that both factors matter, but heretical schools matter much more. This indicates, in part, what it was about big cities that attracted the Valentinians: they were intellectual and cultural centers conducive to nonconformity, in addition to being large enough that the nucleus of members needed to form a local congregation could be found.

Montanism

Had they appeared in modern times, the followers of Montanus would probably have been designated as a “doomsday cult.” Their two primary tenets were that Montanus and his two female associates, Priscilla and Maximilia, had the gift of prophecy (achieved during states of ecstasy), and that their most important prophecy was that the end was very near. “After me there will no longer be a prophet, but the end,”73 was how Maximilia put it. It also has long been assumed (based on writings by Eusebius and by Tertullian) that the Montanists were eager for martyrdom, but they probably were “not substantially different from” other Christians in that regard.74

Fundamentally, the heresy of the Montanists lay in their claim to have gained authentic new revelations and in their method for gaining revelations, rather than the content of these revelations. To condone continuing revelations puts all religious organizations at serious risk of constant doctrinal upheavals; thus most religious groups, after the founders are gone, prohibit or monopolize revelations.75 Moreover, in this particular circumstance, condoning revelations gained during ecstatic states came far too close to embracing pagan oracles.76 As for doctrinal matters, even late in the second century, when Montanus first began to preach and prophesy, many church fathers still accepted that the Day of Judgment was near. Nor did the rest of the Montanist teachings and practices differ in other than minor ways from that of the conventional church; “prophecy was the primary point of contention.”77

MAP 6-3. Valentinian Congregations

Consequently, historians agree that the Montanists were not Gnostics, but merely heretics—the words Montanus and Montanism do not even appear in the indexes of most of the leading books on Gnosticism. Thus, Montanism provides a useful basis for comparison with other movements.

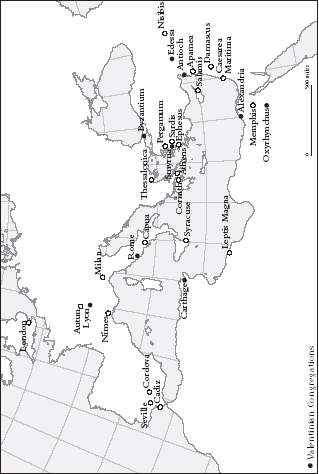

See Map 6-4, which identifies the twenty-two cities with Montanist congregations.78 You will note that there is less of an eastern tilt to this map than to many of the other maps.

Since historians do not consider the Montanists Gnostics, it follows that:

HYPOTHESIS 6-9: Montanist congregations were not more common in cities having heretical schools.

The data revealed no significant difference between cities with and without heretical schools as to the presence of Montanist congregations (Table 6-9). The hypothesis is confirmed.

While the Montanists seem not to have been Gnostics, they were condemned as heretics. That being the case, on the basis of Fischer’s subcultural theory: Montanists ought to have been more successful in the larger cities:

HYPOTHESIS 6-10: Montanist congregations were more common in larger cities than in smaller ones.

All of the larger cities had Montanist congregations, compared with 61 percent of the smaller cities (Table 6-10). The difference is significant, and the hypothesis is confirmed.

Montanism was not significantly correlated with Christianization or with the Diaspora, however.

Manichaeism

The ‘prophet’ Mani managed to be declared a heretic in both the East (by the Zoroastrian state church in Persia) and the West. Born in 216 CE in Mesopotamia, he was related to the local nobility through his mother and was enrolled in a “Judeo-Christian baptismal sect with gnostic and ascetic features”79 by his father at age four. He began receiving revelations at age twelve, and at twenty-four received one in which he was ordered by an angel to begin his ministry.

Unfortunately, because he was a Persian and missionized quite successfully in the East, several generations of scholars, especially in Germany, erroneously dismissed Manichaeism as a Persian religion. Their error repeated one made in 279 CE by Emperor Diocletian, who issued an edict against the Manichaeians as “Persians who are our enemies.”80 This was nonsense. As Peter Brown put it, the “Manichees entered the Roman Empire not as…[an] Iranian religion…but at the behest of a man who claimed to be an ‘Apostle of Jesus Christ’: they intended to supersede Christianity, not spread a [Persian faith.]”81 Manichaeism was, in the words of Christoph Markschies, “the culmination and conclusion of ‘Gnosis.’”82

As to what Mani taught, it was the well-worn Gnostic account of an evil creator and an evil world, with some especially scandalous details. It was not Adam but an evil archon who had sex with Eve and fathered Cain. Then Cain had sex with his mother and fathered Abel. Later Eve managed to arouse the ascetic Adam to father Seth, thus beginning a race of beings who are noble in spirit but “entrapped in innately evil material bodies.”83

MAP 6-4. Montanist Congregations

Mani created two levels of membership: the Auditors and the Elect. The former ‘heard’ the word but did not live a life that could qualify for admission to the Kingdom of Light upon their death. Rather, they could hope only to be reborn as vegetables and then to be eaten by the Elect and “belched” to freedom from the evil archons and sent on their way to the Kingdom of Light. As for the Elect, they were bound by extraordinary restrictions: no sex, no alcohol, no meat, no baths, and virtually no physical activity of any kind. They could meet these requirements only if Auditors waited on them hand and foot.

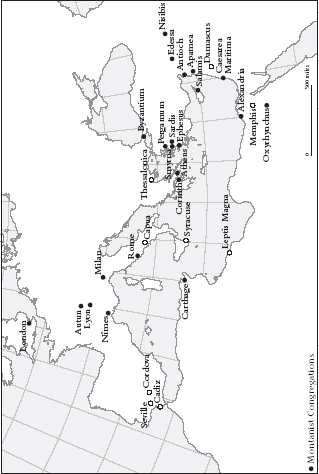

The Manichaeians enjoyed some success. They missionized far eastward (into China), making converts even among the nobility, as well as far westward—the young St. Augustine was a Manichaean for a few years (but only as an Auditor and without giving up his mistress). The favorable response to Manichaeism can be seen in Map 6-5.84

If, as Pheme Perkins put it, “Manichaeism [was] the last powerful manifestation of Gnostic spirituality in the ancient world,”85 it follows that:

HYPOTHESIS 6-11: Manichaeist congregations were more common in cities having heretical schools than in cities without.

This hypothesis is very strongly supported. Like Valentinianism, Manichaeism did better where there were heretical schools (Table 6-11).

Since the Manichaeists also were heretics, it follows that:

HYPOTHESIS 6-12: Manichaeist congregations were more common in larger cities than in smaller ones.

Seventy-five percent of the large cities had Manichaeist congregations, compared with 17 percent of the smaller cities (Table 6-12). This, then, is another confirmation of Fischer’s subcultural theory of urbanism.

Manichaeism was not significantly correlated with Christianization or with the Diaspora.

The Demiurgists: ‘Gnosticism’ Reconceived

Probably the primary flaw in the immense literature on Gnosticism has been a lack of discrimination. If the early church fathers condemned any work as heresy, it was likely to be treated as an instance of Gnosticism. If manuscripts were found stuffed in the same big earthen pot, that was prima facie evidence that each was a Gnostic work (aside from some obvious exceptions, such as a portion of Plato’s Republic). But, despite all the variations that have invalidated the term Gnostic as an analytic category, clearly there is something here—a subset of manuscripts, schools, and movements that share a particularly outlandish heresy: that there are two gods and that the one who created and controls the world is utterly evil and inferior to the supreme God, who is good but remote.

In the conclusion of his book on the inadequacies of Gnosticism as a historical concept, Michael Williams proposed that his colleagues narrow their scope to this subgroup of heresies and dispense with the label Gnosticism as hopelessly compromised. He suggested that this subgroup be named “biblical demiurgical” and that “it would include all sources that made a distinction between the creator(s) and controllers of the material world and the most transcendent divine being, and that in so doing made use of Jewish or Christian scriptural traditions.”86 For ease of expression, it would seem adequate to refer to these sources as the Demiurgists, who embraced Demiurgism, with the understanding that the term is limited to those within the Judeo-Christian tradition.

The bases for this new concept, and for treating these instances as members of a single class, have been evident in some of the analyses pursued above. It will be useful to bring these results into focus by examining how these movements are correlated with heretical schools. Theologically, both the Valentinians and the Manichaeists were Demiurgists, and so were the major heretical schools. These three measures are very highly intercorrelated, as should be the case with members of a common class. Moreover, the Marcionists and Montanists are not statistically part of this Demiurgical cluster, just as would be predicted from their doctrines (Correlations 6-1).

MAP 6-5. Manichaeist Congregations

When one has identified several measures of the ‘same’ thing, it often is useful to combine them into a single measure—in this case, by adding the three measures of Demiurgism together into what we might call the index of Demiurgism. Previous results involving the individual measures of Demiurgism indicated that it was not an aspect of the sociocultural ‘set’ that has been the primary focus of this study. In support of this view, the index of Demiurgism is unrelated to Christianization, the Diaspora, Hellenism, or ports. However, the Demiurgical heresies were very highly correlated with city-size (Correlations 6-2). Just as in modern America one does not seek exotic cults in Peoria or Fargo, but in New York and Los Angeles, so too in ancient times one found them in Rome, Alexandria, Antioch, and the other major centers.

Conclusion

In some sense it is true that there were ‘many’ Christianities during the first several centuries. But, contrary to the wild claims made by members of the Jesus Seminar and by other media-consecrated experts concerning the lack of an early Christian consensus, the dissidents were mostly gadflies—even Marcion was easily turned away. As often is the case with gadflies, some were sufficiently annoying as to provoke significant responses: Marcion did prompt the early church to create a scriptural canon, for example. But the more overwhelming fact is that these heretics did not pose any real threat to the Christian church, if for no other reason than that their doctrines were so bizarre and the religious practices advocated by most of them (including non-Demiurgists) were so extreme as to appeal only to the few. As doctrines define behavioral prohibitions, they can matter a lot! Even if their friends and relatives do join, most people will not readily embrace a life of austere denial—a loveless, sexless, childless, meatless, bathless existence—especially if it offers no greater or more plausible posthumous rewards (the long shot chance to become an Elect belch, for example) than does a faith that is far less restrictive. For most Greco-Romans, it was far more attractive to be a conventional Christian or indeed to remain a pagan.

MITHRAEUM. The pagan cult of Mithraism met in underground caverns like this one excavated beneath the Church of San Clemente in Rome. Dozens of Mithraea have been found, and since all of them were as small as this one, the congregations could not have numbered more than fifty men. (Women were not allowed.)