Chapter 2

You Are What You Eat: The Link between Your Diet and Your Heart

In This Chapter

Identifying the eight key factors that contribute to your overall heart health

Identifying the eight key factors that contribute to your overall heart health

Determining how many calories you need each day

Determining how many calories you need each day

Lowering your total fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol intake

Lowering your total fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol intake

Reducing the sodium in your diet

Reducing the sodium in your diet

Getting more antioxidants in the foods you eat

Getting more antioxidants in the foods you eat

Assessing the healthfulness of your diet

Assessing the healthfulness of your diet

N ot long ago, at my research laboratory, a man who had just finished an 18-week dietary intervention study sat down with a research dietitian to review his cholesterol results. The purpose of the study he participated in was to see if following a healthful, low-saturated-fat diet, which included a whole-grain, oat, ready-to-eat cereal, could lower cholesterol levels in adults. The man’s cholesterol results revealed a distinct correlation between the amount of saturated fat in his diet and the level of his LDL cholesterol (see “Controlling Your Fat and Cholesterol Intake,” later in this chapter for more information on the different forms of cholesterol). When he ate the most saturated fat during the study, his LDL cholesterol was at its highest, and when he ate the least saturated fat during the study, his LDL cholesterol was at its lowest. When the dietitian pointed this out to him, he excitedly said, “You mean what I eat makes a difference in my cholesterol level?”

You bet it does! What you eat makes a big difference not only in your cholesterol levels but also in other risk factors for heart disease, including obesity, high blood pressure, and diabetes. Your diet can also help you promote healthy coronary arteries. In this chapter, I give you the information you need in order to make the link between these scientific facts and the issues you encounter every day, particularly selecting and preparing heart-healthy foods.

Understanding the Eight Key Eating Habits

Hundreds of scientific studies have established that your eating habits and food choices can either increase or decrease your risk of heart disease. In the following list, I highlight the eight key factors these studies point to, all of which affect your risk of heart disease:

The number of calories you consume

The number of calories you consume

The amount of total fat you consume

The amount of total fat you consume

The amount of saturated fat you consume

The amount of saturated fat you consume

The amount of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fat you consume

The amount of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fat you consume

The amount of cholesterol you consume

The amount of cholesterol you consume

The amount of fiber you consume

The amount of fiber you consume

The amount of sodium you consume

The amount of sodium you consume

The amount of antioxidant-rich foods you consume

The amount of antioxidant-rich foods you consume

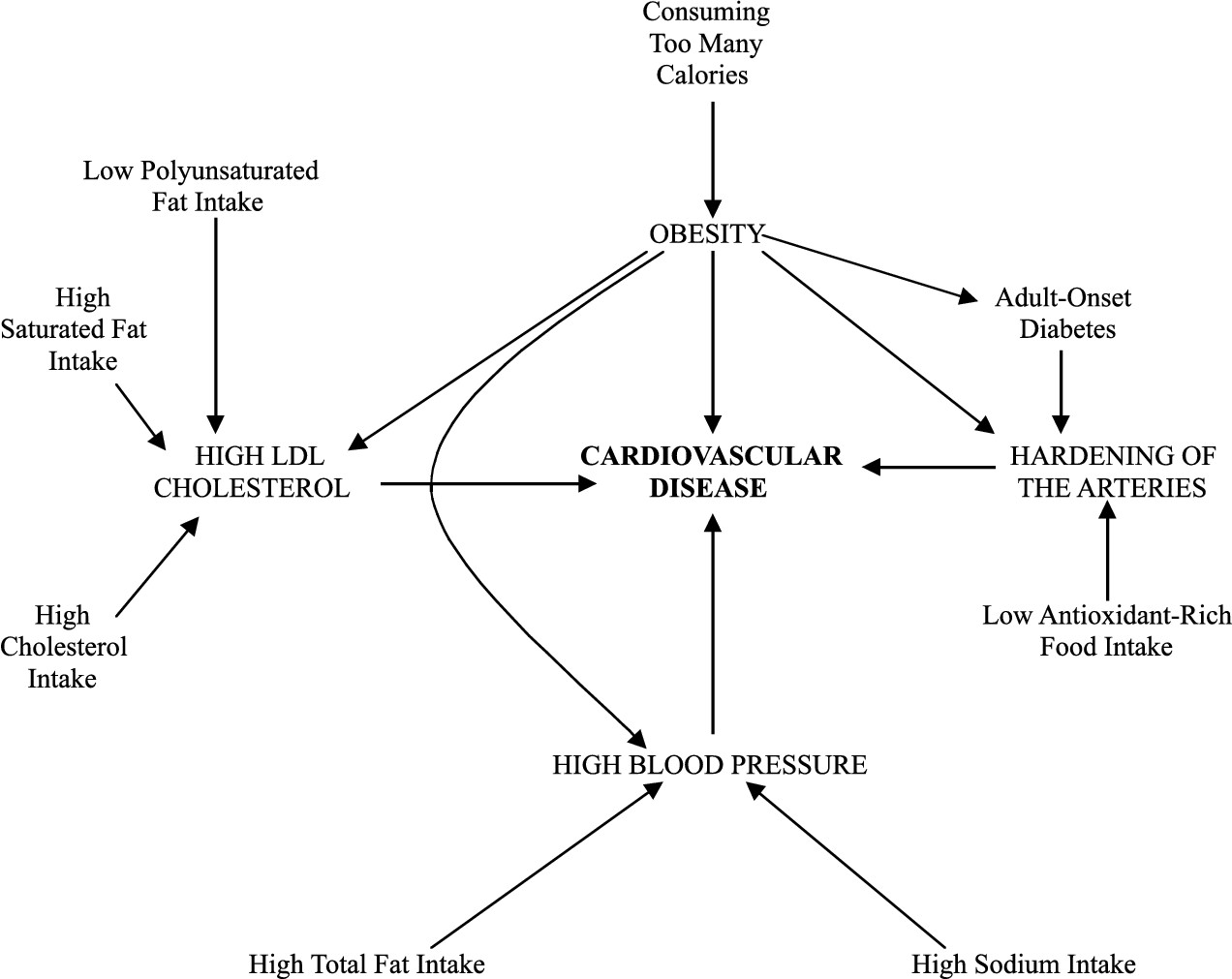

Figure 2-1 illustrates the way these key eating habits or food choices influence individual risk factors and your overall risk of heart disease.

|

Figure 2-1: Diet-related factors that influence your risk for cardiovascular disease. |

|

These eight key eating practices don’t refer to specific foods; instead, they refer to nutrients that are found in a wide variety foods. My research dietitians are fond of reminding me that “People eat food, not nutrients.” So rather than focusing heavily on nutrients, I try, in this book, to keep the information practical and easy to use. But this chapter establishes an important foundation for the practical shopping strategies, cooking techniques, and great recipes you can find in the rest of the book. In order to provide you with this foundation, I give you a brief look at how nutrients such as saturated fat, cholesterol, and sodium contribute to obesity, elevated blood cholesterol, and high blood pressure — all of which are risk factors for heart disease. I also discuss nutrients (such as antioxidants, phytochemicals, and fiber) that you should eat more of in order to decrease your risk of cardiovascular disease.

Calories Count

Although healthy-heart cooking doesn’t ask you to count calories, calories do count in helping you achieve and/or maintain a healthy weight. And the nutrient value in the calories you consume is important to heart health, too.

A calorie is a way of measuring the amount of energy that is available in the foods you eat, which your body uses to fuel all its functions. Calories come from four major nutrient groups: fat, protein, carbohydrates, and alcohol. All calories are equal in energy, but not in their nutritive value for the human body. For example, a bag of potato chips and a banana may have the same number of calories (about 150). But where the potato chips provide mainly fat calories, which, in excess, contribute to elevated cholesterol and high blood pressure, the banana provides carbohydrate calories, the foundation of good nutrition, as well as essential vitamins and minerals. That’s why you want to select wisely when preparing or selecting a meal or snack. You want to get the most bang for your nutrition buck, so choose foods that not only provide calories you need for energy but also nutrients you need for good health. All the recipes in this book can fit within a heart-healthy way of eating. In addition, I provide a nutritional analysis with each recipe so you can tell what you’re getting and plan accordingly.

Everyone needs a certain number of calories (a certain amount of energy) each day to maintain his or her body weight. (Of course, your daily calorie intake varies, but it is your average calorie intake over time that matters.) The number of calories you consume has a direct effect on your body weight:

When you consistently eat more calories than you need, your body weight increases. Just 50 extra calories each day (the amount in two Hershey’s Kisses), over the span of one year, would lead to a 5-pound weight gain. Over time, weight gain may lead to obesity, one of the major risk factors for heart disease.

When you consistently eat more calories than you need, your body weight increases. Just 50 extra calories each day (the amount in two Hershey’s Kisses), over the span of one year, would lead to a 5-pound weight gain. Over time, weight gain may lead to obesity, one of the major risk factors for heart disease.

When you consistently eat fewer calories than you need, your body weight decreases. Your body weight may also decrease if you eat the same number of calories as you have in the past but increase your level of exercise. Increasing activity increases the need for energy (which means you burn more calories).

When you consistently eat fewer calories than you need, your body weight decreases. Your body weight may also decrease if you eat the same number of calories as you have in the past but increase your level of exercise. Increasing activity increases the need for energy (which means you burn more calories).

Figuring out how many calories you need

Your daily caloric need is based on a number of factors, including gender, age, height, weight, body composition, health status, and physical activity level. But the two biggest determinants of calorie needs are current body weight and physical activity level.

Table 2-1 gives you a quick and easy way to determine how many calories you need based on your activity level and your current body weight. Find your current activity level in the table, and locate the number that corresponds with your gender. Then multiply that number, called a metabolic multiple, by your current weight in pounds. The resulting number gives an estimate of your current calorie needs.

| Women | Men | Activity Level |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 12 | Sedentary lifestyle (no regular physical activity) |

| 12 | 15 | Sedentary to average lifestyle (mild aerobic exercise |

| less than 2 hours per week) | ||

| 15 | 17 | Average to active lifestyle (2 to 4 hours of regular |

| aerobic exercise per week) | ||

| 17 | 20 | Active lifestyle (daily regular aerobic exercise more |

| than 4 hours per week) |

For example, Mary takes three 45-minute aerobics classes each week, which means she exercises for a total of 2 hours and 15 minutes, which translates to an average to active lifestyle. Her metabolic multiple is 15. Mary weighs 150 pounds. Multiplying her metabolic multiple by her current body weight indicates she needs about 2250 calories per day to maintain her weight. Compare this to Sue who also weighs 150 pounds but who never engages in physical activity. Sue’s metabolic multiple is 10. Multiplying her metabolic multiple by her current body weight indicates that Sue only needs 1500 calories per day to maintain her weight. As you can see, the more you exercise, the more food you can eat and still maintain your weight.

Why can men eat more than women?

Why does a man have a higher metabolic multiple than a woman if they both engage in the same amount of physical activity? Because men tend to have more muscle mass than women do (male hormones, specifically testosterone, account for this difference in body composition). Muscle is more metabolically active than fat, bone, and other non-muscle components of the body. So, pound for pound, men simply burn more calories than women do.

Looking at the connection between your caloric intake and your heart’s health

Even small amounts of weight gain substantially increase your risk of heart disease. By the time that you are 20 percent overweight (the medical definition of obese ), you have doubled your risk of heart disease. Obesity also interacts strongly and negatively with other risk factors for heart disease such as cholesterol and lipid problems, high blood pressure, and diabetes.

If your current pattern of eating is maintaining your body weight within an optimal range for health, as indicated by your body mass index (BMI), then you are on the right track. You can assess your current body weight by using the BMI chart included in Chapter 1. A BMI between 19 and 24 is optimal; a BMI between 25 and 29 indicates you’re overweight, and a BMI of 30 or higher indicates obesity. If you are overweight or obese, the best thing you can do to reduce your risk of heart disease is lose weight.

Losing weight

If you need to lose a few pounds (or more) to improve your health, remember that the payoff for modest weight loss is huge. Losing weight, even 5 percent of your current body weight, can help reduce your cholesterol level, reduce your blood pressure, and reduce the risk of adult-onset diabetes, all of which are risk factors for heart disease.

To lose those pounds, you can cut calories, burn more calories, or do both. To cut your caloric intake, you need to cut back on the amount of food you eat. I recommend cutting back on empty-calorie and high-fat foods, such as sodas, candy, and fried foods. I don’t recommend cutting out entire foods groups, such as dairy or grain products; doing so may give you an inadequate supply of nutrients. To burn more calories, you need to get more physical activity and exercise. If you eat less and increase your physical activity, you’ll have the best plan for successful weight loss and weight management.

If you want to explore the topic of weight management more thoroughly, refer to Dieting For Dummies or seek assistance from a medical professional, such as a registered dietitian who specializes in weight management.

Controlling Your Fat and Cholesterol Intake

Fat and cholesterol are both vital nutrients, used by your body to perform specific functions. However, when you consume too much fat or cholesterol, they can be damaging to your body instead of helping it. Most importantly, eating too much fat or cholesterol increases the level of cholesterol in your blood and contributes to the development of heart disease. In the following sections, I explain cholesterol and fat in terms that are easy to understand, and I let you know how you can watch your fat and cholesterol intake to maintain a healthy heart.

The cholesterol connection

The amount and type of fat you consume and the amount of dietary cholesterol you consume have an important connection to a major risk factor for heart disease: They influence the amount of cholesterol and other lipids (fats) in your blood.

Cholesterol is a naturally occurring waxy substance present in human beings and all other animals. It is an important component of the body’s cell walls. The body also requires cholesterol to produce many hormones (including sex hormones) as well as the bile acids that help to digest food. Humans get cholesterol from two sources: Our livers produce cholesterol and we consume it in animal products (particularly meat, eggs, and dairy).

How high cholesterol contributes to heart disease

The higher your level of blood cholesterol, the greater your risk of coronary artery disease. If your cholesterol is above 200 mg/dl, your risk of heart disease increases dramatically. If your cholesterol is above 240 mg/dl, your risk of dying from heart disease is more than two times greater than the risk faced by individuals whose cholesterol level is below 200 mg/dl. Generally speaking, the lower your cholesterol level is below 200 mg/dl, the better.

The good news is that lowering your overall blood cholesterol level even a smidgen can make a positive difference. And the more you lower it, the greater the benefit. It is estimated that for every one point that your cholesterol drops, your risk of heart disease drops by 2 percent. Thus, a drop in your overall cholesterol of 10 points can decrease your risk of heart disease by 20 percent. Except for a few people who have inherited a predisposition to high cholesterol, the amount and type of fat and the amount of cholesterol in food you consume play the most important role in keeping your blood cholesterol levels low or in lowering them if they are too high.

“Bad” versus “good” cholesterol

Cholesterol as a whole, however, is made up of different types of substances, some of which are bad for your heart health and some of which are good. Cholesterol travels around the blood stream on complex structures called lipoproteins, which are made up of cholesterol or other fats (lipids) and proteins (now you know how they got the fancy name). Lipoproteins can be separated and measured according to their weight and density. They range all the way from very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) to high-density lipoproteins (HDL). Some lipoproteins are dangerous to your heart and some are helpful.

One particularly dangerous form of cholesterol is called low density lipoprotein (LDL). LDL cholesterol is dangerous because it contains more fat and less protein, making it fairly unstable. Because LDL cholesterol is unstable, it’s prone to fall apart, making it easy for the LDL cholesterol to adhere to artery walls.

On the other hand, a beneficial type of lipoprotein called high density lipoprotein (HDL) can actually help protect your heart from heart disease. HDL cholesterol is stable, so it does not adhere to artery walls the way LDL cholesterol does. Instead, it actually helps carry cholesterol away from the artery walls, which is particularly important for the coronary arteries.

Controlling the total amount of fat, the kinds of fat, and the cholesterol you consume in your daily diet can do a lot to help you lower your overall cholesterol, as well as lower the bad LDLs and increase the good HDLs. The following sections look at how.

Fat: The good, the bad, and the sludgy

Fat has gotten a bad rap as an evil substance that raises cholesterol, makes people fat, and increases their risk of cancer. The truth is that there are many types of fat, some harmful and some helpful. Fat comes in three basic forms:

Saturated fat. This kind of fat is typically found in animal sources, although some fats from plants such as cocoa butter, palm oil, and coconut oil are also saturated. Trans fats (unsaturated fats that are turned into solid form, such as margarine, through the process of hydrogenation) function like saturated fats. Typically, saturated fats and trans fats are solid at room temperature. Eating saturated fat promotes increased LDL cholesterol (the “bad” cholesterol) levels; that’s why cutting back on saturated fat intake can help reduce your LDL cholesterol level.

Saturated fat. This kind of fat is typically found in animal sources, although some fats from plants such as cocoa butter, palm oil, and coconut oil are also saturated. Trans fats (unsaturated fats that are turned into solid form, such as margarine, through the process of hydrogenation) function like saturated fats. Typically, saturated fats and trans fats are solid at room temperature. Eating saturated fat promotes increased LDL cholesterol (the “bad” cholesterol) levels; that’s why cutting back on saturated fat intake can help reduce your LDL cholesterol level.

Monounsaturated fat. Derived from vegetable sources, such as olive, canola, and peanut oil, monounsaturated fat is typically liquid at room temperature. Recent evidence has suggested that consuming monounsaturated fats (particularly when part of a Mediterranean diet featuring olive oil) can significantly lower the risk of heart disease by raising HDL cholesterol (the good cholesterol that helps remove the bad LDL cholesterol from your blood) without raising total cholesterol.

Monounsaturated fat. Derived from vegetable sources, such as olive, canola, and peanut oil, monounsaturated fat is typically liquid at room temperature. Recent evidence has suggested that consuming monounsaturated fats (particularly when part of a Mediterranean diet featuring olive oil) can significantly lower the risk of heart disease by raising HDL cholesterol (the good cholesterol that helps remove the bad LDL cholesterol from your blood) without raising total cholesterol.

Polyunsaturated fat. Like monounsaturated fat, polyunsaturated fat also comes primarily from vegetable sources and is typically liquid at room temperature. Corn oil and most other salad oils are examples of polyunsaturated fats. Although saturated fats may raise your LDL cholesterol (the “bad” cholesterol) level and monounsaturated fats may raise your HDL cholesterol (the “good” cholesterol) level, polyunsaturated fats may reduce your VLDL cholesterol (another type of harmful blood cholesterol) levels. Polyunsaturated fat from cold-water fish (referred to as omega-3 fatty acids) provide other heart health benefits. More information on these benefits come later in this chapter.

Polyunsaturated fat. Like monounsaturated fat, polyunsaturated fat also comes primarily from vegetable sources and is typically liquid at room temperature. Corn oil and most other salad oils are examples of polyunsaturated fats. Although saturated fats may raise your LDL cholesterol (the “bad” cholesterol) level and monounsaturated fats may raise your HDL cholesterol (the “good” cholesterol) level, polyunsaturated fats may reduce your VLDL cholesterol (another type of harmful blood cholesterol) levels. Polyunsaturated fat from cold-water fish (referred to as omega-3 fatty acids) provide other heart health benefits. More information on these benefits come later in this chapter.

All fat-rich foods contain a combination of the three basic types of fat, but the proportions of the three types of fat vary greatly. For example, only 6 percent of the fat in canola oil is saturated, whereas 87 percent of the fat in coconut oil is saturated. Experts recommend choosing dietary fats with the least amount of saturated fat and the greatest amount of monounsaturated fat. The following sections provide specific suggestions on limiting your intake of fat.

DASH to lower your blood pressure

Do you know that you can DASH to lower your blood pressure by increasing your consumption of fruits and vegetables and cutting your fat intake back?

DASH refers to a large clinical study called Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension. This study examined the effects of the DASH Eating Plan on blood pressure. The DASH Eating Plan emphasizes whole-grain foods and encourages a high consumption of fruits and vegetables (8 to 10 daily servings). It also encourages people to eat 4 to 5 servings of nuts, seeds, and legumes every week as well as 2 to 3 servings of low-fat and nonfat dairy products every day. Finally, it suggests cutting fat intake back to less than 30 percent of your total caloric intake.

The results of the DASH study were very impressive. The DASH diet was just as effective in lowering blood pressure as blood pressure medication in many participants with moderate hypertension.

Here are four things you can do to adopt the DASH Eating Plan:

Increase your intake of fruits and vegetables to at least eight servings each day.

Increase your intake of fruits and vegetables to at least eight servings each day.

Increase your intake of low-fat or nonfat calcium-rich dairy products to at least two servings each day. For adequate calcium intake, many people (especially post-menopausal women not taking hormone-replacement therapy) need 3 to 4 servings of calcium-rich foods each day.

Increase your intake of low-fat or nonfat calcium-rich dairy products to at least two servings each day. For adequate calcium intake, many people (especially post-menopausal women not taking hormone-replacement therapy) need 3 to 4 servings of calcium-rich foods each day.

Center your meals around beans, rice, pasta, and vegetables instead of meat to reduce your fat intake and increase your nutrient intake. The recipes in this book feature lots of these very healthful foods.

Center your meals around beans, rice, pasta, and vegetables instead of meat to reduce your fat intake and increase your nutrient intake. The recipes in this book feature lots of these very healthful foods.

Keep your fat intake low. Keep in mind that you can’t eat a few more servings of fruits and vegetables while still eating a high-fat diet and expect your blood pressure to drop dramatically.

Keep your fat intake low. Keep in mind that you can’t eat a few more servings of fruits and vegetables while still eating a high-fat diet and expect your blood pressure to drop dramatically.

For more information on the DASH Eating Plan, request information from:

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Information Center P.O. Box 30105 Bethesda, MD 20824-0105

Read more about the DASH Eating Plan online at dash.bwh.harvard.edu or on the Web site of The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at www.nhlbi.nih.gov.

Limiting the total fat in your diet

Because of the negative role excess fat can play in health, experts such as the American Heart Association and the American Dietetic Association recommend that you limit the total amount of fat in your diet to less than 30 percent of your total calorie intake.

Recent studies suggest that reducing dietary fat intake to less than 25 percent of your total calorie intake may help you lower your blood pressure and cholesterol level, as well as helping you to lose weight. Cutting back on calories from dietary fat also leaves room for calories from non-fat foods such as fruits and vegetables, which contain nutrients such as magnesium and potassium that lower blood pressure.

Lowering your intake of saturated fat

Use lean meats such as poultry, all seafood, lean cuts of beef (eye of round and top round, for example), lean cuts of pork (pork tenderloin, for example), and 95 percent lean ground beef.

Use lean meats such as poultry, all seafood, lean cuts of beef (eye of round and top round, for example), lean cuts of pork (pork tenderloin, for example), and 95 percent lean ground beef.

Switch to skim or nonfat milk.

Switch to skim or nonfat milk.

Eat low-fat and nonfat cheeses and dairy products.

Eat low-fat and nonfat cheeses and dairy products.

Use soft tub margarine instead of butter.

Use soft tub margarine instead of butter.

Avoid packaged cookies, crackers, and other foods that contain tropical oils such as coconut, palm, or palm kernel oil.

Avoid packaged cookies, crackers, and other foods that contain tropical oils such as coconut, palm, or palm kernel oil.

If a product has very little total fat, it will also have very little saturated fat. Chapter 4 provides more tips on choosing products with the least amount of saturated fat. Chapter 19 also offers more tips on reducing your cholesterol level.

Emphasizing monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats

Although saturated fat is detrimental to your heart health, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats may both have beneficial effects on your heart health.

Monounsaturated fat, when used in place of saturated fat, helps raise levels of HDL cholesterol. The following are good sources of monounsaturated fat:

Olive oil. A whopping 74 percent of the fat in olive oil is monounsaturated.

Olive oil. A whopping 74 percent of the fat in olive oil is monounsaturated.

Canola oil. Ranking second, 62 percent of the fat in canola oil is monounsaturated.

Canola oil. Ranking second, 62 percent of the fat in canola oil is monounsaturated.

Other sources: Peanuts, natural peanut butter, olives, and avocados are also good sources of monounsaturated fat.

Other sources: Peanuts, natural peanut butter, olives, and avocados are also good sources of monounsaturated fat.

Polyunsaturated fats are found in a variety of foods, but the best known for their effects on heart health are the omega-3 fatty acids. Omega-3 fatty acids are a type of polyunsaturated fat found in cold water fish. Research indicates that the regular consumption of fish rich in omega-3s reduces the risk of heart disease. Omega-3s appear to reduce the risk of heart disease by reducing VLDL cholesterol levels (another type of bad cholesterol), lowering blood pressure, and reducing the stickiness of platelets. Eating fish just two to three times each week may reduce your risk of heart disease.

Cutting your cholesterol intake

Plants do not produce cholesterol — only animals can make cholesterol, so the cholesterol in foods you eat comes from animal products such as dairy products with fat, egg yolks, meat, seafood, and poultry. The American Heart Association recommends limiting dietary cholesterol intake to 300 milligrams per day. You can limit your intake of cholesterol in three easy ways:

Choose nonfat or low-fat dairy products. If a dairy product doesn’t contain any fat, it won’t contain any cholesterol either.

Choose nonfat or low-fat dairy products. If a dairy product doesn’t contain any fat, it won’t contain any cholesterol either.

Limit your total intake of meat to less than 6 ounces per day. Unlike dairy products, lean meat doesn’t always have a low cholesterol content, because cholesterol is present in flesh as well as in fat and skin. The amount of cholesterol in a very high-fat meat, such as salami, is actually less than the amount of cholesterol in an equal amount of skinless chicken! One ounce of salami has 17 milligrams of cholesterol, whereas 1 ounce of chicken has 25 milligrams of cholesterol. By limiting your total meat intake each day, you can limit your cholesterol intake as well.

Limit your total intake of meat to less than 6 ounces per day. Unlike dairy products, lean meat doesn’t always have a low cholesterol content, because cholesterol is present in flesh as well as in fat and skin. The amount of cholesterol in a very high-fat meat, such as salami, is actually less than the amount of cholesterol in an equal amount of skinless chicken! One ounce of salami has 17 milligrams of cholesterol, whereas 1 ounce of chicken has 25 milligrams of cholesterol. By limiting your total meat intake each day, you can limit your cholesterol intake as well.

Use liquid oil or soft tub margarine instead of butter or lard. Although 1 tablespoon of olive oil, 1 tablespoon of soft margarine, and 1 tablespoon of butter all have 110 to 130 calories and 12 to 14 grams of total fat, butter and other animal fats have cholesterol (vegetable fats don’t) and more saturated fat. So vegetables fats are always preferable.

Use liquid oil or soft tub margarine instead of butter or lard. Although 1 tablespoon of olive oil, 1 tablespoon of soft margarine, and 1 tablespoon of butter all have 110 to 130 calories and 12 to 14 grams of total fat, butter and other animal fats have cholesterol (vegetable fats don’t) and more saturated fat. So vegetables fats are always preferable.

Fighting cholesterol with fiber

Consuming more fiber can help you fight the good fight against cholesterol and other health threats such as certain cancers. Fiber only comes from plant-based foods. No matter how hard you look you will never find any fiber in animal-based foods such as milk, meat, fish, or cheese. Fiber contains no calories but is considered an essential dietary component. Guidelines for healthy eating recommend that you consume 25 to 30 grams of fiber each day. Most Americans get only half that amount.

There are two types of fiber — soluble and insoluble:

Soluble fiber combines with water and fluids in the intestine to form gels that can absorb other substances and trap them. The trapped substances include bile acids that contain a lot of cholesterol. Thus, soluble fiber is particularly good as a way of lowering cholesterol because, as bile acids are excreted from the body, the liver uses up cholesterol to make more bile acids.

Soluble fiber combines with water and fluids in the intestine to form gels that can absorb other substances and trap them. The trapped substances include bile acids that contain a lot of cholesterol. Thus, soluble fiber is particularly good as a way of lowering cholesterol because, as bile acids are excreted from the body, the liver uses up cholesterol to make more bile acids.

Two types of soluble fiber have been proven to have substantial benefits:

• Whole-grain oat products such as oatmeal, Cheerios cereal (and its clones), and products containing oat bran: These products are so effective that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has allowed certain foods rich in such soluble fiber to make the health claim that, when used in conjunction with a low-fat diet, these foods may further lower your risk of heart disease.

• Psyllium: Another natural fiber that helps to lower your cholesterol, psyllium can be found in certain breakfast cereals (such as Kellogg’s Bran Buds) and is also available in supplements such as Metamucil. Note that the supplemental forms of psyllium are not for everyone, because they may cause gas and other uncomfortable side effects for some individuals and because they may also interfere with certain heart and blood pressure prescriptions by slowing the absorption of certain drugs. Talk with your doctor before taking a psyllium supplement, and go easy on psyllium cereals.

Insoluble fiber, what many people call “roughage,” contains benefits that are not related to heart disease. For example, this type of fiber helps trap water in the stools, providing more bulk and helping food move through the digestive system more quickly. This effect may help lower the risk of colon cancer.

Insoluble fiber, what many people call “roughage,” contains benefits that are not related to heart disease. For example, this type of fiber helps trap water in the stools, providing more bulk and helping food move through the digestive system more quickly. This effect may help lower the risk of colon cancer.

Both soluble and insoluble fiber are found in a wide variety of foods. The most fiber-rich foods include

Whole grain breads

Whole grain breads

Berries

Berries

Black beans and other legumes

Black beans and other legumes

Lentils

Lentils

Nuts and seeds

Nuts and seeds

Butter versus margarine: The trans fatty acid wars

After years of hearing “butter is bad” consumers then started hearing “margarine is worse.” The confusion arose over the issue of trans fatty acids, which are created when oils are hydrogenated, a process that makes the oils solid at room temperature, more stable, and more flavorful. Trans fatty acids have the same effect on our bodies as saturated fat: They raise blood cholesterol levels.

So what’s a health conscious-consumer supposed to do? Margarine is still the better choice for day-to-day use. Look for soft tub margarines that list a liquid vegetable oil as the first ingredient. These margarines contain very little trans fat compared to stick margarines or those that list a partially hydrogenated oil as the first ingredient. Trans-fat-free margarines (such as Promise and Smart Beat margarines) are an even better choice, if you can find them.

Recently, two new margarines have arrived on supermarket shelves that may help promote healthy cholesterol levels. Benecol Spread (made by McNeil Consumer Products, a division of Johnson & Johnson) and Take Control Spread (made by Lipton, a division of Unilever) are margarines with unique ingredients that help lower cholesterol levels. Benecol Spread contains a substance derived from pine tree sap that inhibits cholesterol absorption in the gut. Studies show that consuming three servings per day for at least two weeks may help lower LDL cholesterol levels by up to 14 percent. Take Control Spread contains a soybean extract that also inhibits cholesterol absorption. Studies suggest that just two servings per day for at least three weeks may lower LDL levels by up to 10 percent. For more information on these products and the other products made with these beneficial substances, visit the product Web sites at www. benecol.com or www.takecontrol.com.

The eggstraordinary news about eggs

Are you wondering why I don’t suggest that you eat fewer eggs? A single large egg has 215 mg of cholesterol, so health professionals have long advised patients with cardiovascular disease to avoid eggs due to their high cholesterol content. The traditional recommendation for all people, in fact, was to eat no more than 3 or 4 whole eggs a week. (Unlimited cholesterol-free egg whites were okay.) And following this recommendation is still a good idea if you have established coronary artery disease or diabetes.

But a number of well-designed, very large studies have found, overall, that egg consumption is not related to elevated cholesterol levels and cardiovascular disease risk. The bottom line is that consuming up to an egg a day poses no increased risk for cardiovascular disease. (The one exception is for people with diabetes. Research has shown that, for some unknown reason, the cholesterol level of people with diabetes is more affected by dietary cholesterol intake. If you have diabetes, limit yourself to 4 egg yolks per week.)

This may be great news if you’re an egg lover who has been feeling deprived lately. But watch what you eat with those eggs. Skip the traditional high-fat accompaniments such as bacon, sausage, buttered toast, and hash browns. Enjoy eggs instead with other healthful foods like whole-grain, unbuttered toast and fresh fruit.

Limiting Your Intake of Sodium

Researchers estimate that about 30 percent of adults in the United States are salt-sensitive, which means that their blood pressure is raised when they consume more sodium. The American Heart Association recommends no more than 2,400 milligrams of sodium per day — a little more than the a teaspoon of table salt (2,300 milligrams). The average American consumes 6,000 to 8,000 milligrams of sodium per day.

High blood pressure, or hypertension, is often called the “silent killer” because it does not typically cause any noticeable symptoms. By any name, high blood pressure is a major risk factor for heart disease. Over 25 percent of adult Americans suffer from high blood pressure. And the older you are, the more likely you are to have it. In addition to being a risk factor for heart disease, high blood pressure is a major risk factor for stroke and kidney failure as well. For optimal health, you should strive to keep your blood pressure below 12 0/80 mm Hg.

.jpg)

Cut back on added salt and salty foods.

Cut back on added salt and salty foods.

Reduce the total amount of fat you eat.

Reduce the total amount of fat you eat.

Eat more fruits and vegetables — a lot more.

Eat more fruits and vegetables — a lot more.

You should still watch your sodium intake even if your blood pressure isn’t high. Too much salt is not beneficial for anyone, and cutting back may be beneficial for many.

.jpg)

Protecting Your Arteries with Powerful Antioxidants

Oxygen is essential for life, but, in certain circumstances, it can wreak havoc on our bodies. Many reactions in the body that require oxygen create substances called free radicals. Also found in cigarette smoke and polluted air, free radicals can damage artery walls, initiate the growth of precancerous cells, and are believed to be responsible for aging. Wherever an artery wall is damaged by a free radical, LDL-cholesterol will collect. When enough LDL cholesterol collects in an artery, that artery becomes clogged, which can lead to a heart attack or stroke.

Antioxidants are substances that combat the negative effects of free radicals. Research supports the notion that a diet rich in antioxidant nutrients is one of the best defenses against free radical damage in the body. The major antioxidant nutrients include vitamin A (also known as beta-carotene ), vitamin C, and vitamin E. (See Table 2-2 for a list of foods rich in antioxidants.)

Fruits and vegetables are the best sources of vitamin A (in its beta-carotene form) and vitamin C. Nuts, seeds, and certain oils are the best sources of vitamin E. A diet rich in citrus fruits and bright green, yellow, or orange vegetables provides adequate amounts of vitamin A and vitamin C, but it is difficult to get enough vitamin E in a low-fat diet. Many health professionals strongly recommend that adults over age 50 take a vitamin E supplement that supplies 200 to 400 International Units (IU) every day. Vitamin E is the most powerful antioxidant nutrient, and getting adequate amounts through supplementation has been associated with reduced risk of cardiovascular disease.

| Foods Richest in Vitamin A | Foods Richest | Foods Richest |

|---|---|---|

| and Beta-Carotene | in Vitamin C | in Vitamin E |

| Apricots | Asparagus | Egg yolks |

| Broccoli | Broccoli | Sunflower seeds |

| Cantaloupe | Cantaloupe | Vegetable oils (look for oils |

| with added vitamin E) | ||

| Carrots | Enriched fruit juices | Wheat germ |

| (look for juices with | ||

| 100 percent vitamin C) | ||

| Egg yolks | Grapefruit | Whole-grain foods (for exam |

| ple, whole-wheat bread) | ||

| Mango | Kiwi fruit | |

| Milk (vitamin A is added to all | Oranges, orange juice | |

| milk in the United States) | ||

| Oranges, orange juice | Potatoes | |

| Pumpkin | Spinach | |

| Spinach | Strawberries | |

| Squash | Sweet potatoes | |

| Sweet potatoes | ||

| Yams |

.jpg)

Hooking up with the fighting phytochemicals: Nature’s gift to health

Phytochemicals are substances created by plants to protect themselves from bacteria, viruses, fungi, and insects. The thousands of phytochemicals in the plant foods we eat may help protect us from a wide range of diseases, including heart disease. Many phytochemical compounds act as antioxidants. Others act as anticancer agents in a wide variety of ways. And where can you find phytochemcials?

One great source is soybeans and the food products made from soybeans, including tofu and soy milk, which are filled with a variety of phytochemicals that reduce the risk of certain cancers and heart disease. Different forms of soy contain different phytochemical components. Check out Chapter 9 for recipes that use tofu, a versatile protein-rich, cholesterol-free substitute for meat.

Here are some other great sources of phytochemicals:

Berries, including cranberries and blueberries

Berries, including cranberries and blueberries

Black or green tea (but not herb tea)

Black or green tea (but not herb tea)

Citrus fruits

Citrus fruits

Vegetables, such as broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, and onions

Vegetables, such as broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, and onions

Fresh herbs

Fresh herbs

Garlic

Garlic

Legumes, such as navy beans, kidney beans, and lentils

Legumes, such as navy beans, kidney beans, and lentils

Nuts

Nuts

Orange and yellow fruits and vegetables like apricots, mango, carrots, and sweet potatoes

Orange and yellow fruits and vegetables like apricots, mango, carrots, and sweet potatoes

Red grapes and red wine

Red grapes and red wine

Soy foods, such as tofu, soy milk, and soy protein powder

Soy foods, such as tofu, soy milk, and soy protein powder

Tomatoes

Tomatoes

Whole grains, including whole wheat, oats, and barley

Whole grains, including whole wheat, oats, and barley

Can I just supplement my way to heart health?

With few exceptions, the best way to eat your way to a healthier heart is by making better food choices. A standard multivitamin/mineral supplement is fine to take if you want a little insurance. But many studies show that greater benefits, such as those I cover in this chapter, come from eating the nutrients in fruits, vegetables, and other foods, not from supplements. Also, don’t think that a supplement can save you from the negative effects of a bad diet.

You may, however, want to consider taking as a supplement three nutrients: calcium, vitamin E, and folate, for reasons I describe below:

Calcium. If you’re a post-menopausal woman not on hormone-replacement therapy, your daily need for calcium is 1,500 milligrams, which is equal to five 8-ounce glasses of skim milk. For most women, that level of calcium intake is difficult without a little help from a supplement. Look for one that also contains vitamin D, which is needed to absorb the calcium.

Calcium. If you’re a post-menopausal woman not on hormone-replacement therapy, your daily need for calcium is 1,500 milligrams, which is equal to five 8-ounce glasses of skim milk. For most women, that level of calcium intake is difficult without a little help from a supplement. Look for one that also contains vitamin D, which is needed to absorb the calcium.

Vitamin E. If you’re over 50 and have a family history of heart disease, taking a vitamin E supplement is a good idea, because vitamin E has been associated with a reduced risk of heart disease. Look for gel caps that contain 200 to 400 international units (IU).

Vitamin E. If you’re over 50 and have a family history of heart disease, taking a vitamin E supplement is a good idea, because vitamin E has been associated with a reduced risk of heart disease. Look for gel caps that contain 200 to 400 international units (IU).

Folate. Folate, also called folic acid, helps lower the blood levels of homocysteine, an amino acid that at high levels has been shown to increase the risks of heart attacks. (Folate is also essential for pregnant women to help prevent certain birth defects.) You can get folate in green leafy vegetables, dried beans, peas, and orange juice, but it’s hard to consume enough. You may want to consider eating a fully fortified whole-grain cereal or taking 400 micrograms (mcg) of folate in a supplement.

Folate. Folate, also called folic acid, helps lower the blood levels of homocysteine, an amino acid that at high levels has been shown to increase the risks of heart attacks. (Folate is also essential for pregnant women to help prevent certain birth defects.) You can get folate in green leafy vegetables, dried beans, peas, and orange juice, but it’s hard to consume enough. You may want to consider eating a fully fortified whole-grain cereal or taking 400 micrograms (mcg) of folate in a supplement.

Putting Science to Work in Your Daily Food Choices

It’s one thing to read the kind of information I provide in this chapter; it’s another thing entirely to make it a part of your daily life. Implementing these healthy lifestyle choices can be daunting. But keep in mind that wise old saying that the journey of a thousand miles starts with a single step. To help you begin this journey, in the next few sections, I take you through a few simple steps that get you off and running.

Evaluating your current eating habits

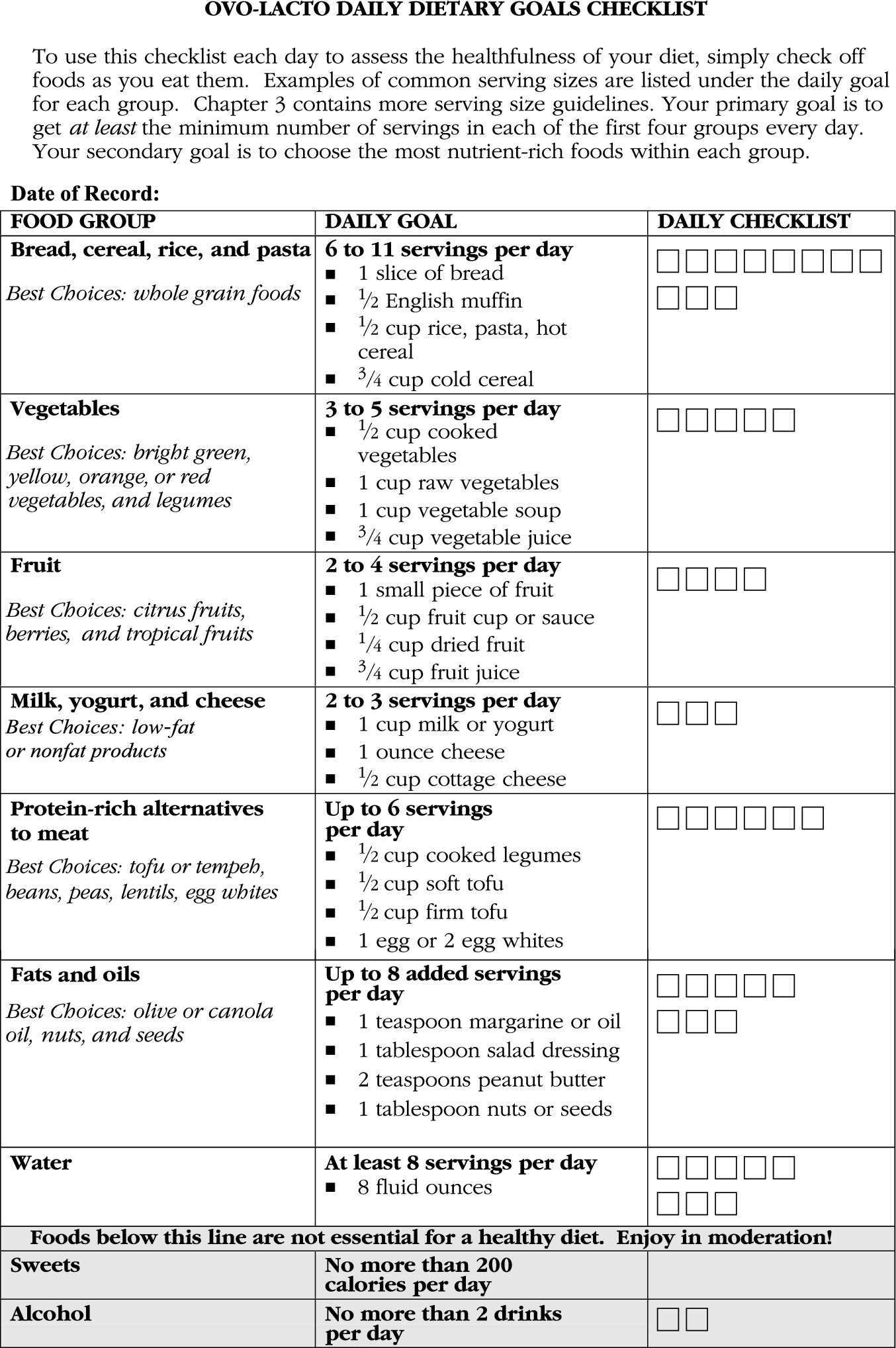

Your first step should be to do a self-evaluation to see if you’re currently eating a balanced diet that includes foods from all the major food groups (grains, vegetables, fruits, dairy products, and protein-rich foods). To help you assess your current eating habits, I provide a checklist for meat-eaters (see Figure 2-2) and another for ovo-lacto vegetarians (see Figure 2-3).

Using the checklist (make several copies before you start), keep a record of everything you eat for at least three days. Then look over the completed checklists to see where your strengths and weaknesses are. Are you eating a balance of foods from all food groups? Or are you falling short in some areas? For example, if most days you don’t get any servings of dairy products (and ice cream doesn’t count!), but you ate at least the minimum of everything else, that’s great. All you need to do is concentrate on getting more dairy products. However, if your diet is bottom heavy, and you’re falling short in many of the nutrient-rich food groups at the top of the checklist, you have some work to do. Consider meeting with a registered dietitian who can help you navigate a sea of dietary changes.

Planning to make some changes

What changes will you make? I suggest you take a two-step approach to making your diet more heart-healthy:

1. Work first on balancing your diet, if you need to.

2. Work to consume the most nutrient-rich foods you can within each group. The checklists indicate characteristics of the most nutrient-rich foods within each group, to get you started.

Enjoying your new lifestyle

While you’re planning your goals, use the recipes in this book for inspiration and enjoyment. We provide over 100 recipes that fit into a heart-healthy way of eating. You’ll find taste treats that range from simple entrées and side dishes to elaborate party dishes. Each recipe has clear, easy-to-follow instructions and most demonstrate heart-healthy cooking techniques that you can use to modify some of your own favorite recipes.

|

Figure 2-2: Dietary goals checklist for meat-eaters. |

|

|

Figure 2-3: Dietary goals checklist for ovo-lacto vegetarians. |

|