Introduction

The defeat went barely noticed by the media. Amid the rolling hills of Quebec’s lush farm and wine region, the small town of Dunham had beaten back oil giants.

Companies like Enbridge and the owners of Portland-Montreal Pipe Line—namely Imperial Oil, Suncor, and Shell—have been trying to construct a pumping station to pipe heavy crude over a nearby mountain range. The infrastructure is integral to Enbridge’s plans to ship Alberta tar sands, via Quebec, to the eastern coast of the United States. But when Enbridge quietly initiated this project in 2008, a coalition of local farmers, residents, and environmentalists formed in opposition. They marched, launched legal challenges, and organized Canada’s first UK-inspired climate camp, which culminated in promises of civil disobedience.1

The oil companies fought back in court. Enbridge dropped the project’s initial name—“Trailbreaker”—in an attempt to fool residents into thinking they had abandoned their wider plans to ship Alberta tar sands eastward. The federal government even dispatched spies to intimidate community organizers. But, ground down by Dunham’s efforts, the companies withdrew in July 2013. They still want a pumping station in Quebec; they just won’t be able to build it in this town.

The triumph may herald the fate of two massive tar sands pipeline projects that loom over central and eastern Canada. The first is Enbridge’s now-unnamed plan, which involves reversing a network of pipelines that currently carry African and European oil from the East Coast to western Canada. This could bring up to three hundred thousand barrels of Alberta tar sands oil daily to the US seaboard, via the Enbridge Line 9 pipeline in Ontario and western Quebec, as well as the Portland-Montreal Pipe Line, which runs between Montreal and the coast of Maine.2 The other plan is TransCanada’s recently announced Energy East project, a $12 billion investment to convert a natural gas pipeline and build an extension in the provinces of Quebec and New Brunswick. It could ship as many as 1.1 million barrels per day to Canada’s coast. Covering 4,400 kilometres, it would require the construction of 1,400 kilometres of new pipeline.3 Both projects would traverse some of the most densely populated areas in the country.

False Promises

Business leaders, politicians, and the mainstream media have intoned patriotically about the potential boost these projects will bring to the prosperity and energy security of Canadians. “This is truly a nation-building project that will diversify our economy and create new jobs here in Alberta and across the country,” Alberta’s then-premier Alison Redford declared about Energy East.4 “Each of these enterprises required innovative thinking and a strong belief that building critical infrastructure ties our country together, making it stronger and more in control of our own destiny,” added TransCanada CEO Russ Girling.5

The exercise in flag-waving is intended to sell a single idea: that the interests of oil companies are the same as those of the population at large. But if the soaring rhetoric is an indication of anything, it is the growing desperation of Alberta’s oil barons and their allies in government. With a protest movement having (so far) blocked the construction of TransCanada’s Keystone XL pipeline south to the Gulf Coast, and Enbridge’s Gateway pipeline west to the Pacific, Alberta’s oil companies are sitting on top of a lot of landlocked bitumen. And as their crude sells at a reduced price, they are losing billions in profit.6

Thus, the frantic drive for an eastern ocean distribution route has nothing to do with the needs of ordinary Canadians: it is an export plan to serve the corporate bottom line. Once the crude reaches the coast, it will fetch higher prices on the world market and go to the highest bidder—the United States, Europe, India, or China. Nor will these tar sands solve Canadians’ need for energy security: as Canada’s oil prices align with the world’s, consumers at the pump may pay even more.

If the oil companies will capture the benefits, everyone else will carry the risks. To start with, tar sands crude is much more corrosive. An international expert on pipeline safety has concluded that there is a “high risk” that Enbridge’s pipeline will rupture because of cracking and corrosion.7 TransCanada’s pipeline, built in the 1950s, is even older. The Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Bay of Fundy, rich ecosystems on which fishing and tourism depend, would be threatened by toxic bitumen. These waters should be protected as a public trust, not exploited as a tanker transit route.

The economic consequences are just as drastic. Every pipeline that is built will further lock Canada into a state of dependency on the export of bitumen, a classic “staples trap” that will weaken an economy that relies on extractive industries. Canada’s petro-dollar has already hollowed out its manufacturing core, destroying hundreds of thousands of jobs. And new pipelines will also lock Canada into carbon-intensive production, at exactly the moment when other countries are transitioning to low-carbon energy and preparing to mitigate the impacts of climate change.8

In other words, these are not pipelines to build a nation. They are a scheme by which to swindle it.

The flimsiness of their case has forced the oil barons to resort to other tactics. To split labour unions away from the opposition, TransCanada and Enbridge have taken to making inflated claims about the jobs that might be created. Their template is being drawn from the fight over Keystone XL in the United States, during which TransCanada promised as many as twenty thousand to forty thousand jobs. When economists crunched the figures, they landed on a different total: as few as a thousand temporary jobs, and only twenty permanent ones.9

Neither company appears to be shying away from conflicts of interest— they seem, in fact, to depend on them. The media has reported that Enbridge is handing out “donations” to municipalities along the path of its Line 9 pipeline, including $44,000 to a police station in Hamilton, Ontario.10 This practice is better described by a simpler term: bribery. And TransCanada has hired a company to lead their lobbying charge in Quebec. Who else have they worked for? The same municipalities they intended to lobby.

Prospects for Opposition

Those opposed to the pipelines must do a better job of countering business proponents, who have suggested that if the Enbridge pipeline is not approved, it would be a “clear signal” that “no economic development [is] possible in Quebec.”11 Such fear mongering about how action on climate change would bring about an economic Armageddon have become common, though no less effective. A local of the Communications, Energy, and Paperworkers (CEP) union in Quebec—now a branch of the new union Unifor—joined a business coalition in supporting the pipeline, hoping that a few hundred refining jobs in Montreal will be revived.12 CEP has argued for the refining of bitumen in Canada instead of exporting abroad, and thus joined the movement against Keystone XL and the Northern Gateway pipeline. But both labour and other voices must do better at highlighting the importance of building economic alternatives into the movement against pipelines, an omission that marked the battle against the Keystone XL, and allowed some US labour leaders to stridently attack the environmentalists leading that campaign.

In Quebec and elsewhere, the movement needs to confront the right-wing narrative on these issues by arguing the facts: investment in a green industrial transition will bring far more jobs—secure, ecological, and socially useful jobs—relative to investment in the infrastructure needed to develop the tar sands.13 Pipelines will create only a few jobs and huge private-sector profits, while burdening the public with long-term environmental damage. The movement must demand loudly that the same workers who shouldn’t be building pipelines or staffing refineries should instead receive good, high-paying jobs, albeit jobs that simultaneously address climate change: retrofitting homes and buildings, erecting high-speed rail and public transit, and building infrastructure to protect against the storms ahead.14

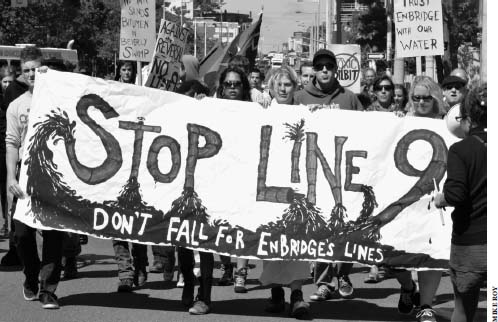

Whatever the limitations of existing campaigns, the pipeline struggles have had an electrifying impact on organizing across Canada. As pipelines have become the most visible—and vulnerable—instruments disfiguring the country’s environment, economy, and democracy, they have spawned an unprecedented development: wherever they have been proposed, their path traces the outlines of a new resistance. Through the summer months of 2013 alone, there were protests in Winnipeg, an occupation in southern Ontario, mobilizations in Ottawa and Toronto, and blockades in New England. The only “nation-building” occurring appears to be a coast-to-coast movement of opposition.

While the resistance in Dunham, Quebec, was the earliest to appear against Enbridge’s eastern pipeline project, it was soon followed by organizing among cities and First Nations communities in southern Ontario. More specifically, organizing has been underway in different boroughs of Toronto, in cities such as Guelph and Kingston, and on Six Nations territory. The regional campaigning against the project has consisted of a set of local campaigns. When locals initiated a six-day blockade of an Enbridge pumping station along the Line in Hamilton in 2013, they were actively supported by activists across southern Ontario. At the western end of Enbridge Line 9, Aamjiwnaang First Nation has been at the centre of other regional protest efforts. This Native community is located within Sarnia in the middle of so-called “Chemical Valley,” one of the most toxic industrial zones in North America (see chapter 13). In 2013, non-Native organizers were drawn to Sarnia for two regional strategy sessions and protests. Campaigners opposing Enbridge’s plans for Line 9 have often stressed the importance of treaty and Aboriginal rights in opposing the shipment of tar sands crude. Indigenous rights pose the biggest obstacle to Canada’s reckless resource extraction agenda—and organizing that prioritizes these rights offers a model for organizers elsewhere.

A Swamp Line 9 rally in Hamilton, Ontario, 2013.

Across the US border, in New England, opposition has also been mounting, building off a rich and varied tradition of environmental and anti-nuclear organizing.15 The Portland-Montreal pipeline, constructed in the 1950s, currently pumps about 400,000 barrels of overseas oil a day from Portland, Maine, and then up through Canada—but it will be reversed as part of Enbridge’s plans to bring oil from the West in Alberta. Environmentalists have closely tracked these plans, and organizing was catalyzed by meetings between activists from Dunham, Quebec, and Vermont and Maine. In February 2013, some two thousand people marched out onto the pier in Portland from where the tar sands would be shipped. A month later, almost thirty Vermont towns became “tar sands-free zones,” passing resolutions against the transport of tar sands through the state in town-hall meetings that are part of a storied, direct democratic tradition dating back hundreds of years. (In the early 1980s, close to two hundred towns in the state passed resolutions for a nuclear weapons freeze, boosting the national anti-nuclear movement.)

But it is the movement simmering in Quebec that may ultimately be the most fiery, and decisive. In the spring and summer of 2011, Quebec residents mobilized for one of the world’s only moratoriums on shale gas exploitation. On Earth Day in April 2013, nearly fifty thousand people marched through Montreal, with a main demand of rejecting the transport of tar sands through the province. Polls regularly indicate that a majority of Quebecers have serious objections to the idea.16 And in the summer of 2013, Quebec’s population was still reeling from the explosion of a train carrying fracked shale oil through the town of Lac-Mégantic. The incident left forty-seven people dead—casualties of deregulation and a boom in dirty, unconventional energy. Quebecers may have to pay the $200 million cleanup costs themselves, after the US company responsible declared bankruptcy to avoid liability.

The former Parti Québécois (PQ) government extended a moratorium on shale gas projects, but their stance on tar sands shipments was in keeping with the close links between top party members and the oil and gas industry. Environment minister Daniel Breton briefly made waves when he harshly criticized the idea of shipping tar sands through Quebec and promised to closely scrutinize the plan. But a few weeks later—the same day that Enbridge filed an application for their pipeline with Canada’s federal energy regulatory body—Quebec’s premier, Pauline Marois, booted Breton out of her cabinet. “A total coincidence,” insisted an Enbridge spokesman.17

In the face of mounting opposition, the Quebec government initially promised a public consultation on the Enbridge pipeline, though not on TransCanada. But it proved to be a charade, as Quebec’s parliamentary commission gave a green light to the reversal of Line 9 in early 2014 (which was soon followed by the National Energy Board’s approval of the reversal of Line 9 in Ontario and Quebec).18 The fact that a Quebec nationalist premier has rarely caved in such a brazen way to the interests of oil corporations and the federal government will no doubt rile much of the Quebec sovereigntist population.19 Unfortunately, the two parties to the PQ’s right—the Liberal Party and Coalition Avenir Québec—are worse on the question of the pipelines, supporting both Enbridge and TransCanada’s projects.

The movement in Quebec has the chance to achieve more than just blocking tar sands pipeline projects in the province. It could set an inspiring international precedent by winning a moratorium on the exploitation and shipment of all extreme fossil fuels, extending the existing moratorium on shale gas by adding to it both tar sands and oil shale, which companies are exploring on Anticosti Island in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. It is a positive sign that the Regroupement interrégional gaz de schiste de la vallée du St-Laurent—the anti-shale gas coalition that includes more than a hundred citizen groups—has changed its mandate to actively oppose all extreme energy sources, including the tar sands pipelines.

For now, the anti–tar sands movement in the province awaits the kind of proactive strategy that was provided for the anti-shale gas movement by the grassroots group Moratoire d’une génération (One-Generation Moratorium). That group issued an ultimatum to the government, completed a six-hundred-kilometre walk across the province, and trained for and promised sustained civil disobedience-galvanizing the movement and prompting the government to respond with a moratorium.20

While mainstream Quebec environmental organizations like Équiterre have laid important educational and media groundwork in the campaign against the tar sands pipelines, a lot will depend on grassroots and rural groups who could generate a plan for coordinated, escalating direct action, much like the campaign against Dunham’s pumping station, on a province-wide scale.

If that can happen, the victory over the oil barons that has been celebrated in the little Quebec farm and wine town will not be the last.