CHAPTER

3

THE POWER OF HYPERFOCUS

INTRODUCING HYPERFOCUS

Think back to your last uber-productive work day, one when you accomplished a huge amount. On that day, chances are a number of things were true.

For starters, you were probably focusing on only one thing—maybe out of necessity, driven by a deadline. This one task filled your attentional space.

You were also likely able to dodge distractions and quickly got back on track every time an interruption did come up. While you were working with intense focus, you weren’t working frantically, constantly switching between tasks. When your attention wandered—which it still did often, but less than usual—you quickly brought it back to the task at hand.

Your work was probably also at a comfortable level of difficulty: not so hard as to be intimidating; not so easy that it could be done out of habit. Because of this, you may have even become completely engrossed in your work, entering a “flow” state, where each time you looked at the clock another hour had flown by, even though you experienced that time as only fifteen minutes. Miraculously, you managed to accomplish the equivalent of several hours of work in each of them.

Finally, once you overcame the hurdle of getting started, you experienced little resistance to continuing. Even though you were working hard, you weren’t exhausted afterward; curiously, you were less tired than after slower workdays. Your motivation remained strong even if you had to stop working because you got hungry or had a meeting or it was time to head home.

On this day you activated your brain’s most productive mode: hyperfocus.*

When you hyperfocus on a task, you expand one task, project, or other object of attention . . .

. . . so it fills your attentional space completely.

You enter this mode by managing your attention deliberately and purposefully: by choosing one important object of attention, eliminating distractions that will inevitably arise as you work, and then focusing on just that one task. Hyperfocus is many things at once: it’s deliberate, undistracted, and quick to refocus, and it leads us to become completely immersed in our work. It also makes us immensely happy. Recall how energized you were by your work the last time you found yourself in this state. In hyperfocus you might even feel more relaxed than you usually are when you work. Allowing one task or project to consume your full attentional space means this state doesn’t make you feel stressed or overwhelmed. Your attentional space doesn’t overflow, and your work doesn’t feel nearly as chaotic. Since hyperfocus is so much more productive, you can slow down a bit and still accomplish an incredible amount in a short period of time.

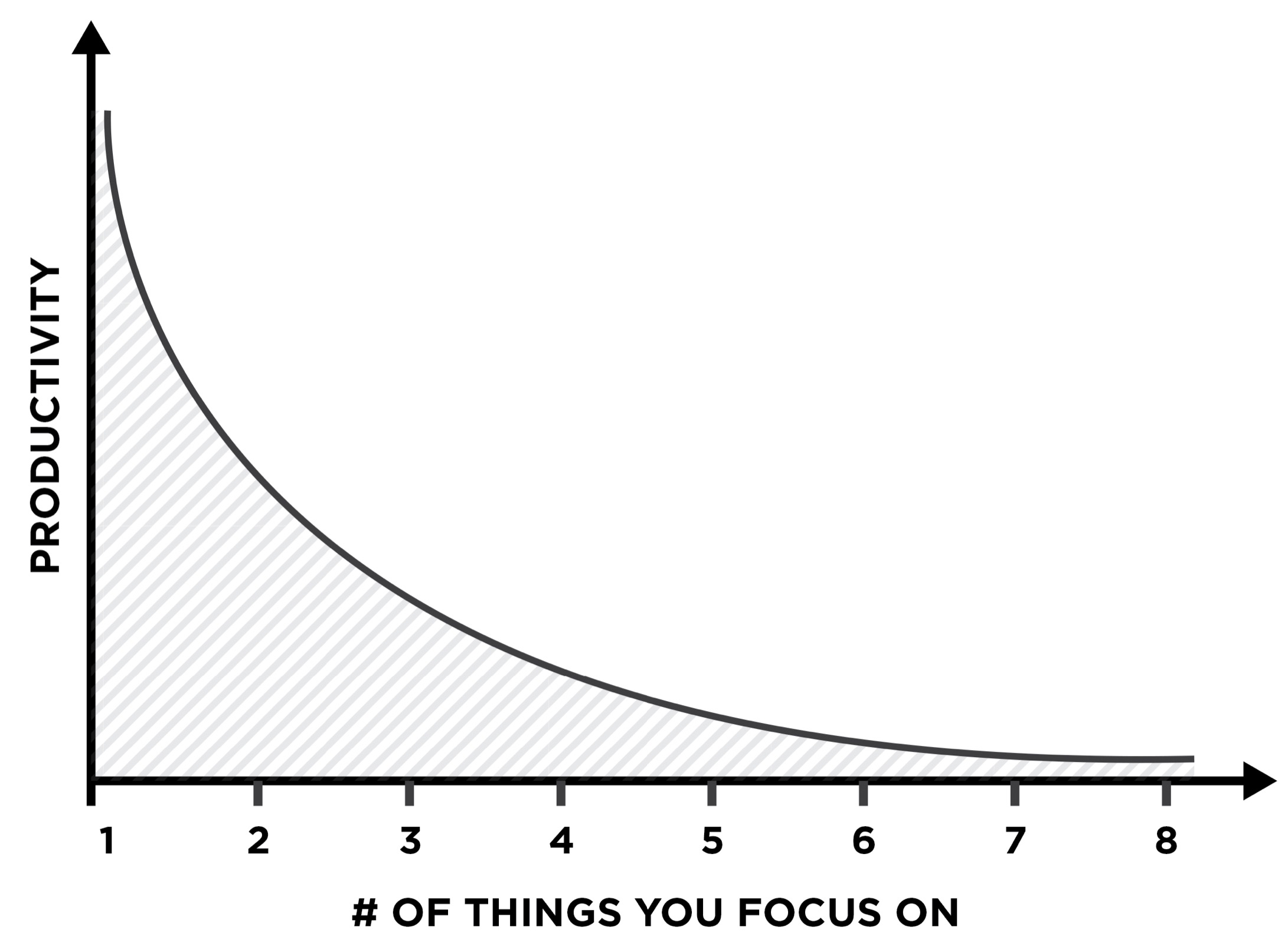

This mode may feel like an elusive luxury in the on-the-go environments in which we work and live today. But nothing could be further from the truth. Hyperfocus means you’re less busy, because you’re permitting fewer objects into your attentional space. Picking which tasks to work on ahead of time lets you focus on what’s actually important in the moment. This has never been more crucial than in our knowledge-work environments, where not all tasks are created equal. You’ll often accomplish more in one hour of hyperfocus than in an entire day spent filling your attentional space to the brim with multiple—and often undeliberate—concerns. This is counterintuitive but absolutely essential advice: the more demands made on your time, the more essential it becomes to choose what—and how many—things you pay attention to. You’re never too busy to hyperfocus.

When it comes to your most important tasks, the fewer things you pay attention to, the more productive you become.

HYPERFOCUSING ON HABITS

The most important aspect of hyperfocus is that only one productive or meaningful task consumes your attentional space. This is simply nonnegotiable. Here’s why: the most critical tasks, projects, and commitments benefit from every bit of extra attention. They’re usually not habits, which by default don’t often consume your full attentional space.

This is not to say it’s impossible to hyperfocus on a habit. There is no task too small to consume your attention—if you tried hard enough, you could commit your complete attention to watching paint dry. But there are two reasons why this mental mode is best preserved for complex tasks, rather than habits.

First, hyperfocus requires willpower and mental energy to activate, drawing from the limited supply we have to make it through the day. Because habits consume so little of our attentional space, there’s really no need to hyperfocus on them.

Second, and more interesting, while your performance on complex tasks benefits when you focus more completely, your habitual-task performance actually suffers when you focus with your total attention.

You may have experienced this the last time you noticed someone watching you walk, and you brought your focus to making sure you walked like a perfectly normal human being. Chances are you immediately started moving like a full-blown mechanical robot, feeling as if you were flailing all over the sidewalk. To put it bluntly, your walking performance suffered.* Or maybe the last time you went bowling you found yourself thinking about why you were scoring more points than usual—what exactly you were doing well. But then your opponents started pulling ahead and eventually won. You choked, and your performance suffered by your bringing your full attention to a game you usually play out of habit. Studies analyzing skilled typists found this same phenomenon: the more attention they brought to their typing, the slower they typed and the more mistakes they made. When doing such habitual tasks, it’s best to not focus completely on what you’re doing.

Save hyperfocus for your most complex tasks—things that will actually benefit from your complete attention, such as writing a report, mapping your team’s budget, or having a meaningful conversation with a loved one.

A few marvelous things happen when you do so. First, because you’re focusing on a single task, you likely have some attentional space to spare—enough that you are also able to keep your original intention in mind. As a result, you are less likely to be derailed by distractions and interruptions, because you have enough awareness to notice that they are about to derail you. And maybe most important, you have enough attention to also think deeply about the task as you work. This allows you to remember and learn more, get back on track when your mind wanders, and consider alternative approaches as you solve problems. All of this will save you an immense amount of time in completing the task. One of the best ways to get more done—and done faster—is by preventing yourself from focusing on things that aren’t important.

THE FOUR STAGES OF HYPERFOCUS

In any given moment you’re focused on either your external environment, the thoughts in your head, or both. Engaging solely with your external environment means you’re effectively living on autopilot. You slip into this mode as you wait for the traffic light to change or find yourself bouncing around a loop of the same apps on your phone. When you’re engaged only with the thoughts in your head, you’re daydreaming. This can happen when you go on a quick walk without your phone, your mind wanders in the shower, or you go for a jog. You enter into hyperfocus when you engage both your thoughts and your external environment and direct them at one thing intentionally.*

So How Do We Enter Hyperfocus Mode?

The science suggests we pass through four states as we begin to focus. First, we’re focused (and productive). Then, assuming we don’t get distracted or interrupted, our mind begins to wander. Third, we make note of this mind wandering. This can take awhile, especially if we don’t frequently check what is consuming our attentional space. (On average, we notice about five times an hour that our mind has wandered.) And fourth, we shift our focus back to our original object of attention.

The four stages of hyperfocus are modeled on this framework.

To hyperfocus, you must

-

choose a productive or meaningful object of attention;

-

eliminate as many external and internal distractions as you can;

-

focus on that chosen object of attention; and

-

continually draw your focus back to that one object of attention.

Setting an intention for what we plan to focus on is the most important step—the more productive and meaningful the task, the more productive and meaningful your actions become. For example, if you set your intention to focus on mentoring a new employee, automating a repetitive task, or brainstorming a new product idea, you’ll be infinitely more productive than if you work intention-free and in autopilot mode.

This same idea applies at home: the more meaningful our objects of focus, the more meaningful our life becomes. We experience the benefits of hyperfocus mode by setting such simple intentions as being present in a conversation with our partner or fully enjoying a meal with our family. We learn more, remember more, and process our actions more deeply—and our lives become more meaningful as a result. This first step to reaching hyperfocus mode is essential—intention absolutely has to precede attention.

The second step to reaching hyperfocus is eliminating as many internal and external distractions as possible. There’s a simple reason we fall victim to distraction: in the moment, distractions are more attractive objects of attention than what we really ought to be doing. This is true both at work and at home. Email alerts that pop into the corner of our screen are usually more tempting than the task we’re doing in another window; the TV behind our partner at the pub is usually more enticing than focusing on the conversation.

Distractions are infinitely easier to deal with in advance—by the time they appear, it’s often already too late to defend our intention against them. Internal distractions must be tamed as well—including random (and sometimes cringeworthy) memories and thoughts that bubble up as we’re trying to focus, the mental resistance we have to unappealing tasks (like doing taxes or cleaning the garage), and the times we want to focus but our mind wants to wander.

Third, hyperfocus becomes possible when we focus on our chosen object of attention for a predetermined amount of time. This involves hunkering down for a set period that is both comfortable and feasible. The more groundwork we lay in the first two steps of hyperfocus, the more deeply and confidently we can accomplish step three.

Fourth, and finally, hyperfocus is about drawing our attention back to the original object of attention when our mind wanders. I’ll repeat this point frequently, as it’s one of the most important ideas in this book: again, research shows that our mind wanders for 47 percent of the day. In other words, if we’re awake for eighteen hours, we’re engaged in what we’re doing for just eight of them. It’s normal for our mind to wander, but the key is to center it so we can spend time and attention on what’s actually in front of us.

In addition, it takes an average of twenty-two minutes to resume working on a task after we’re distracted or interrupted. We fare even worse when we interrupt or distract ourselves—in these cases, it takes twenty-nine minutes to return to working on the original task. The more often we assess what’s occupying our attentional space, the quicker we’re able to get back on track. Don’t stress too much about this right now—we’ll get to specifics later in the book.

The concept of hyperfocus can be summed up in a single tranquil sentence: keep one important, complex object of attention in your awareness as you work.

Choosing What to Focus On

Attention without intention is wasted energy. Intention should always precede attention—in fact, the two ideas pair perfectly. Intention setting allows us to decide how we should spend our time; focusing our attention on that task gets it done efficiently. The best way to become more productive is to choose what you want to accomplish before you begin working.

When we set intentions, it’s important to remember that not all work tasks are created equal. Some tasks enable us to accomplish an incredible amount with every minute we spend on them. These include such goals as setting aside time to plan what main tasks you want to accomplish each day, mentoring a new employee who joined your team a month ago, and writing that book you’ve been meaning to for years. These tasks fall into the “necessary” and “purposeful” quadrants discussed in chapter 1. When you measure work in these quadrants against unnecessary and distracting tasks like attending useless meetings, catching up on your social media feeds, and repeatedly checking for new email, it’s not hard to see which are more productive. When we don’t choose which quadrants of tasks to spend time on, we fall into autopilot.

This is not to say that we can’t “get by” in autopilot mode. By being ultraresponsive to the work that comes our way, we can stay on top of most of it and probably be productive enough to not lose our jobs. But autopilot also fails to progress our work in any meaningful way. I suspect you don’t get paid simply to play the role of “traffic cop” by moving emails, conversations, and instant messages around. Such tasks, and answering unanticipated demands that come your way, are always necessary. But whenever possible, you should take an active role in choosing where you spend your time and attention.

If you haven’t done so already, this is a great time to create a 2 x 2 grid of your work—sorting your standard monthly tasks based on whether they’re productive or unproductive and attractive or unattractive. The ironic thing about investing in your productivity is that it’s almost impossible to do when you’re slogging it out in the office trenches. There’s simply too much to keep up with—meetings, email chains, and project deadlines included. For this reason, the best productivity tactics are the ones that require you to step back and remove yourself from your work so you have the mental space to think critically about how you should approach that work differently. That way, when you return to work, you can do it more intelligently, instead of just harder. Figuring out your four types of work tasks is one of these “stepping back” activities. Now is the best time to do so—especially before you read the very next section. It’ll take just five to ten minutes.

In researching attention and intention over the last few years, I’ve developed a few favorite daily intention-setting rituals. Here are my top three.

1. The Rule of 3

You can probably skim this section if you’re familiar with material I’ve written in the past. If not, allow me to introduce the Rule of 3: at the start of each day, choose the three things you want to have accomplished by day’s end. While a to-do list is useful to capture the minutiae of the day, these three intention slots should be reserved for your most important daily tasks.

I’ve done this little ritual every morning for several years, ever since learning about it from Microsoft’s director of digital transformation, J. D. Meier. The Rule of 3 is deceptively simple. By forcing yourself to pick just three main intentions at the start of each day, you accomplish several things. You choose what’s important but also what’s not important—the constraints of this rule push you to figure out what actually matters. The rule is also flexible within the constraints of your day. If your calendar is packed with meetings, those commitments may dictate the scope of your three intentions, while an appointment-free day means you can set intentions to accomplish more important and less urgent tasks. When unexpected tasks and projects come your way, you can weigh those new responsibilities against the intentions you’ve already set. Because three ideas fit comfortably within your attentional space, you can recall and remember your original intentions with relative ease.

Make sure to keep your three intentions where you can see them—I keep mine on the giant whiteboard in my office or, if I’m traveling, at the top of my daily to-do list, which is synced between devices in OneNote. If you’re like me, you may also find it handy to set three weekly intentions, as well as three daily personal intentions—such as disconnecting from work during dinner, visiting the gym before heading home from the office, or gathering receipts for taxes.

2. Your Most Consequential Tasks

A second intention-setting ritual I follow is considering which items on my to-do list are the most consequential.

If you have the habit of maintaining a to-do list (which I highly recommend and whose power I will discuss later in the book), take a second to consider the consequences of carrying out each task—the sum of both its short-term and long-term consequences. The most important tasks on your list are the ones that lead to the greatest positive consequences.

What will be different in the world—or in your work or in your life—as a result of your spending time doing each of the items on your list? What task is the equivalent of a domino in a line of one hundred that, once it topples over, initiates a chain reaction that lets you accomplish a great deal?

Another way to look at this: when deciding what to do, instead of considering just the immediate consequences of an activity, also consider the second- and third-order consequences. For example, let’s say you’re deciding whether to order a funnel cake for dessert. The immediate consequence of the decision is that you enjoy eating the cake. But the second- and third-order consequences are quite a bit steeper. A second-order consequence might be that you’ll feel terrible for the rest of the evening. Third-order consequences might include gaining weight or breaking a new diet regimen.

This is a powerful idea to internalize, especially since the most important tasks are often not the ones that immediately feel the most urgent or productive. Writing a guide for new hires may not, in the moment, feel as valuable as answering a dozen emails, but if that guide cuts down on the time it takes to bring each new employee on board, makes her feel more welcome, and also serves to make her more productive, it is easily the most consequential thing on your list. Other consequential tasks might include automating a task that’s annoying and repetitive, disconnecting so you can focus on designing the workflow for an app you’re building, or forming an office mentorship program that lets employees easily share their knowledge.

If you have a lot of tasks on your to-do list, ask yourself: which are the most consequential? This exercise works well in tandem with the four types of tasks in your work. Once you’ve separated them into the four quadrants of necessary, purposeful, distracting, and unnecessary, ask yourself: Out of the necessary and purposeful tasks, which have the potential to set off a chain reaction?

3. The Hourly Awareness Chime

Setting three daily intentions and prioritizing your most consequential tasks are great ways to be more intentional every day and week. But how can you ensure you’re working intentionally on a moment-by-moment basis?

As far as productivity is concerned, these individual moments are where the rubber meets the road—it’s pointless to set goals and intentions if you don’t act toward accomplishing them throughout the day. My favorite way to make sure I’m staying on track with my intentions is to frequently check what’s occupying my attentional space—to reflect on whether I’m focusing on what’s important and consequential or whether I’ve slipped into autopilot mode. To do so, I set an hourly awareness chime.

A key theme of Hyperfocus is that you shouldn’t be too hard on yourself when you do notice your brain drifting off or doing something else weird. Your mind will always wander, so consider how that might present an opportunity to assess how you’re feeling and then to set a path for what to do next. Research shows that we are more likely to catch our minds wandering when we reward ourselves for doing so. Even if you minimize one or two distractions and set just one or two intentions each day, you’re doing better than most. If you’re anything like me, your hourly awareness chime may at first reveal that you’re usually not working on something important or consequential. That’s okay—and even to be expected.

The important thing is that you’re regularly checking what’s occupying your attentional space. Set an hourly timer on your phone, smartwatch, or another device—this will easily be the most productive interruption you receive throughout the day.

When your hourly chime rings, ask yourself the following:

-

Was your mind wandering when the awareness chime sounded?

-

Are you working on autopilot or on something you intentionally chose to do? (It’s so satisfying to see this improve over time.)

-

Are you immersed in a productive task? If so, how long have you spent focusing on it? (If it was an impressive amount of time, don’t let the awareness chime trip you up—keep going!)

-

What’s the most consequential thing you could be doing right now? Are you working on it?

-

How full is your attentional space? Is it overflowing, or do you have attention to spare?

-

Are there distractions preventing you from hyperfocusing on your work?

You don’t have to answer all of these questions—pick two or three prompts that you find most helpful, ones that will make you refocus on what’s important. Doing this hourly increases all three measures of attention quality: it helps you focus longer because you spot and prevent distractions on the horizon; you notice more often that your mind has wandered and can refocus it; and you can, over time, spend more of your day working intentionally.

When you first start this check-in, you probably won’t fare so well and will find yourself frequently working on autopilot, getting distracted, and spending time on unnecessary and distracting tasks. That’s fine! When you do, adjust course to work on a task that’s more productive, and tame whatever distractions derailed you in that moment. If you notice the same distractions frequently popping up, make a plan to deal with them. (We’ll do this in the next chapter.)

Try setting an hourly awareness chime for one workday this week. While at first the interruptions will admittedly be annoying, they’ll establish a valuable new habit. If you don’t like the idea of an awareness chime, try using a few cues in your environment that trigger you to think about what’s occupying your attentional space. I no longer use an hourly awareness chime, though I found it to be the most helpful method to get into the practice. Today I reflect on what I’ve been working on during a few predetermined times: each time I walk to the washroom, when I leave my desk to get water or tea, or when my phone rings. (I answer the call after a few rings, once I’ve reflected on what was occupying my attentional space.)

HOW TO SET STRONGER INTENTIONS

Over the last few decades Peter Gollwitzer has been one of the most renowned contributors to the field of intention. He’s perhaps best known for his groundbreaking research on the importance of not only setting intentions but also making them very specific. While we often achieve our vague intentions, specific intentions greatly increase our odds of overall success.

Let’s say, for example, you rushed to set your personal intentions this morning and came up with this list:

-

Go to the gym.

-

Quit working when I get home.

-

Get to bed by a reasonable time.

I’ve deliberately made these intentions vague, but how can we make them more specific and likely to stick?

First, it’s worth considering how effective these intentions are as I’ve formulated them. They will certainly prove to be more effective than doing nothing. In fact, Gollwitzer’s research discovered that even vague intentions like these boost your odds of successfully carrying them out by around 20 percent to 30 percent. So, if you’re lucky, you might cross another one or two off the list. Not bad!

Setting more specific intentions, however, does something remarkable: it makes our odds of success much higher. In one study, Gollwitzer and his research colleague Veronika Brandstätter asked participants to set an intention to complete a difficult goal over Christmas break—such as completing a term paper, finding a new apartment, or settling a conflict with their significant other. Some students set a vague intention while others set what Gollwitzer calls an “implementation intention.” As he explains the term: “Make a very detailed plan on how you want to achieve what you want to achieve. What I’m arguing in my research is that goals need plans, ideally plans that include when, where, and which kind of action to move towards the goal.” In other words, if a student’s vague goal was to “find an apartment during Christmas break,” his implementation intention could be “I will hunt for apartments on Craigslist and email three apartment landlords in the weeks leading up to Christmas.”

Comparing Gollwitzer and Brandstätter’s two participant groups is where things get interesting. A remarkable 62 percent of students who set a specific implementation intention followed through on their goals. The group that did not set an implementation intention fared a lot more poorly, following through on their original intention a third as often—a paltry 22 percent of the time. This effect, which subsequent studies validated further, was positively staggering. Setting specific intentions can double or triple your odds of success.

With that in mind, let’s quickly turn my three vague intentions into implementation intentions:

-

“Go to the gym” becomes “Schedule and go to the gym on my lunch break.”

-

“Quit working when I get home” is reframed as “Put my work phone on airplane mode and my work laptop in another room, and stay disconnected for the evening.”

-

“Get to bed by a reasonable time” becomes “Set a bedtime alarm for 10:00 p.m., and when it goes off, start winding down.”

Implementation intentions are powerful in much the same way as habits. When you begin a habit, your brain carries out the rest of the sequence largely on autopilot. Once you have a game plan for an implementation intention, when you encounter the environmental cue to initiate it—your lunch break rolls around, you get home after a stressful day at work, or your bedtime alarm goes off—you subconsciously get the ball rolling to accomplish your goals. Your intentions take almost no effort to initiate. As Gollwitzer and Brandstätter put it, “action initiation becomes swift, efficient, and does not require conscious intent.” In other words, we begin to act toward our original goal automatically.

Gollwitzer told me that the intentions do not necessarily have to be precise if they are specific enough for a person to understand and identify the situational cues: “We did studies with tennis players, and they made plans on how they want to respond with the problems that might come up in the game. Some of the tennis players were specifying ‘when I get irritated’ or ‘when I get nervous.’ That is not very specific or concrete, but it worked brilliantly because they knew what they meant with ‘nervous.’ Specific means the person can identify the critical situation.”

There are two notable caveats to setting specific intentions. First, you have to actually care about your intentions. Implementation intentions don’t work nearly as well for goals that don’t especially matter to you or that you’ve long abandoned. If you had a goal in the 1990s to amass the world’s largest collection of Furbys, you’ll probably be a lot less motivated to achieve that goal today.

Second, easy-to-accomplish intentions don’t have to be as specific. Deciding in advance when you’ll work on a task is significantly more important for a difficult one than when your intention is to do something simple. If it’s the weekend, and your intention is to go to the gym at least once, you don’t need to be as definite about when you’ll do so. If you’re trying to accomplish something more challenging, though, like saying no to dessert at the restaurant on Saturday, setting a more specific intention is essential. That vague intention can become more specific by planning, when you see the dessert menu, to politely decline and treat yourself to a decaf coffee instead. This caveat works well for intentions at home, but when Monday rolls around, you may need to again set more thoughtful intentions. “When the goals are tough, or when you have so many goals and it’s hard to attain them all, that’s when planning works particularly well,” Gollwitzer adds.

STARTING A HYPERFOCUS RITUAL

The next chapter focuses on taming the external and internal distractions that inevitably derail hyperfocus. However, before discussing these, I want to offer a few simple strategies to begin hyperfocusing on your intentions. These will become infinitely more powerful as you learn to tame the distractions in your work in advance.

Let’s first cover how to focus, and then when. Both ideas are pretty simple.

How to hyperfocus:

-

Start by “feeling out” how long you want to hyperfocus. Have a dialogue with yourself about how resistant you feel toward the mode, particularly if you’re about to hunker down on a difficult, frustrating, or unstructured task. As an example: “Do I feel comfortable focusing for an hour? No way. Forty-five minutes? Better, but still no. Thirty minutes? That’s doable, but still . . . Okay, twenty-five minutes? Actually, I could probably do that.” It’s incredibly rewarding to experience your hyperfocus time limit increase over time. Push yourself—but not too hard. When I started practicing hyperfocus, I began with fifteen-minute blocks of time, each punctuated by a five- to ten-minute distraction break. Hyperfocusing all day would be a chore, and a few stimulating distractions are always fun, especially at first. You’ll soon become accustomed to working with fewer distractions.

-

Anticipate obstacles ahead of time. If I know I have a busy few days coming up, at the beginning of the week I like to schedule my hyperfocus periods—several chunks of time throughout the week that I’ll use to focus on something important. This way, I make sure to carve out time to hyperfocus, instead of getting swept up in last-minute tasks and putting out proverbial fires. Such planning lets my coworkers and assistant know not to book me during these times, and it also reminds me when I’m committed to focus. In weeks like these, a few minutes of advance planning can save hours of wasted productivity.

-

Set a timer. I usually use my phone for this, which might sound ironic, given the distractions it can bring. If these phone distractions will cause a focus black hole, either put it on airplane mode or use a watch or other timer.

-

Hyperfocus! When you notice that your mind has wandered or that you’ve gotten distracted, bring your attention back to your intention. Again, don’t be too tough on yourself when this happens—this is the way your brain is wired to work. If you feel like going for longer when your timer rings—which you probably will because you’ll be on a roll—don’t stop.

That covers the how. Here are a few suggestions that I have found work for deciding when you should hyperfocus:

-

Whenever you can! Naturally, we need time for the little things, but the more you can hyperfocus, the better. Throughout the week, you should schedule as many blocks of time to hyperfocus as your work will allow, and for as long as you personally feel comfortable. We’re the most productive and happy when we work on one meaningful thing at a time, so there’s no reason not to spend as much time in this mode as we possibly can. Whenever you have an important task or project and a window in which you can work on it, don’t pass up the opportunity to hyperfocus—you’ll be missing out on a lot of productivity if you do. Naturally, because of the nature of our jobs, we often have to do a lot of collaborative work, which necessitates our being available to our colleagues. But when you’re working on a task that only you can do, it’s the perfect time to enter into hyperfocus mode.

-

Around the constraints of your work. Most of us don’t have the luxury of hyperfocusing whenever we wish. Productivity is often a process of understanding our constraints. On most days we will be able to find a few opportunities to hyperfocus, and on others it simply won’t be possible. I find the latter to be especially the case while traveling, when I’m at a conference, or when I have a day full of exhausting meetings. Make sure you account for time and energy constraints—and if possible, work around these obstacles when you’re planning your week.

-

When you need to work on a complex task. While I started hyperfocusing by scheduling blocks of time into my calendar, I now enter into the mode whenever I’m working on a complex task or project that will benefit from my full attention. If I’m just checking my email, I won’t set an intention to hyperfocus, but if I’m writing, planning a talk, or attending an important meeting, I invariably do.

-

Based on how averse you are to what you intend to accomplish. The more aversive you find a task or project, the more important it is to tame distractions ahead of time. You’re most likely to procrastinate on tasks that you consider boring, frustrating, difficult, ambiguous, or unstructured, or that you don’t find rewarding or meaningful. In fact, if you call to mind something you’re putting off doing, chances are it has most of these characteristics. The more aversive a task, the more important it is that we enter into a hyperfocused state so we can work on the task with intention.

BUILDING YOUR FOCUS

Over the next several chapters, I’ll give you the tools you need to develop your focus. As you’ll find, your ability to hyperfocus depends on a few factors, all of which affect the quality of your attention:

-

How frequently you seek out new and novel objects of attention. (This is often why we initially resist a hyperfocus ritual.)

-

How often you habitually overload your attentional space.

-

How frequently your attention is derailed by interruptions and distractions.

-

How many tasks, commitments, ideas, and other unresolved issues you’re keeping in your head.

-

How frequently you practice meta-awareness (checking what’s already consuming your attention).

As we’ll discuss, even your mood and diet can influence hyperfocus. For these reasons and more, everyone has a different starting point when it comes to entering the mode.

Ironically, when I first started exploring the research on how we best manage our attention, I could hardly focus for more than a few minutes before becoming distracted. This is often the case when we continually seek novel objects of attention and work in a distracting environment.

While experimenting with the research, I’ve been able to steadily increase the amount of time I can hyperfocus, and I’ve grown accustomed to working with fewer distractions. I wrote the sentence you’re now reading near the end of a forty-five-minute hyperfocus session—my third of the day. These sessions have enabled me to write exactly 2,286 words in around two hours. (This is one of the fun parts about writing a book about productivity: you can verify that your methods actually work by using them to write the book itself.) The third session was my last hyperfocus block, and between those periods I caught up on email, enjoyed checking social media, and had a quick chat with a coworker or two.

But right now isn’t one of those times. And focusing on just one thing—writing these words—is what has allowed me to be so productive over the last forty-five minutes. It’ll work for you too.