THE MEDICI FAMILY is said to have been descended from a knight called Averardo, who fought for Charlemagne during his conquest of Lombardy in the eighth century. According to Medici family legend, Averardo was travelling through the Mugello, a remote valley near Florence, when he heard tell of a giant who was terrorising the neighbourhood. Averardo went in search of the giant, and challenged him. As they faced each other, the giant swung his mace. Averardo ducked and the iron balls from the giant’s mace smashed into his shield; but eventually Averardo managed to slay the giant. Charlemagne was so impressed when he heard of Averardo’s feat that he decreed that henceforth his brave knight could use his dented shield as his personal insignia.

The Medici insignia of red balls (or palle) on a field of gold is said to derive from Averardo’s dented shield. Others claim that the Medici were, as their name suggests, originally apothecaries dispensing medicines to the public, and that the balls of their insignia were in fact pills. This story was always denied by the Medici, and their denial is supported by historical evidence, as the medical use of pills did not become common-place until some time after the appearance of the Medici insignia. The most likely origin of their insignia is the sign that medieval money-changers hung outside their shops, depicting coins. Money-changing was the initial Medici family business.

The legendary knight Averardo settled in the Mugello, the fertile valley of the River Sieve, which runs through the mountains twenty-five miles by road to the north-east of Florence. Even today, the region remains a picturesque spot with vineyards and olive groves either side of the curving river, beneath steep wooded hills and the mountains beyond. This isolated region of less than twenty square miles must have had an exceptional gene pool: not only did it produce the multi-talented Medici, but also the families of geniuses as disparate as Fra Angelico, Galileo and Giotto. The Medici family came from the village of Cafaggiolo, and was always to retain strong links with this spot.

Some time before the turn of thirteenth century the Medici family appears to have left Cafaggiolo to try their luck in Florence. They were not the only country people to seek their fortune in Florence at around this time, and between the mid-twelfth and mid-thirteenth centuries the population of Florence is said to have increased fivefold to more than 50,000. Medieval methods of ascertaining the population were notoriously fanciful, which leaves such figures open to question. The census-taking methods of Florence were a case in point: births were registered by the simple method of counting beans – when a child was born, the family was expected to drop a bean into the local census box: black for a boy or white for a girl. However, we know that Florence experienced an unprecedented increase in population during this period, making it larger than Rome or London, though it remained smaller than the great medieval centres of Paris, Naples and Milan.

The Medici settled in the neighbourhood of San Lorenzo, clustered about the church of San Lorenzo, the earliest part of which had been consecrated in the fourth century. As a result, San Lorenzo would become the patron saint of the Medici, and some of the family’s most illustrious sons would be named after him. From San Lorenzo it was just a few minutes’ walk to the Mercato Vecchio (Old Market), the hub of the city’s commercial life (now the large central Piazza della Repubblica). Here visitors came from miles around to buy the cloth for which the city was famous, with bolts of brightly coloured material laid out on the trestle stalls, cut to measure against the customer as he bargained. Early in the morning the streets leading to this large square would be filled with the carts of farmers bringing their wares to market, the squeals of driven pigs, bleating sheep, the mooing of milk cows. Amidst the cries of the sellers and animals, there were stalls selling freshly caught fish from the Arno, slices from hooked slabs of bloody meat, varieties of cheeses, wine from the barrel. Along the walls were neatly stacked piles of coloured vegetables and fruit – onions and withered greens in the spring; fennel and figs, cherries and oranges in summer; and in winter, meagre piles of earthy root vegetables. Amidst the throng of townsfolk and yokels, the mendicant friars in their threadbare robes begged from passers-by. The blare of a herald’s trumpet, and the crowd would throng the entrance to the Via del Corso to watch a bloodied, stumbling criminal in rags and chains being whipped through the street amidst jeers, on his way to the Bargello and a public hanging on the morrow.

The first Medici mentioned in the records of Florence is one Chiarissimo, who appears on a legal document dated 1201. Little is known of exactly what happened to the family during this period; all we know for certain is that the Medici became money-changers and gradually prospered – to such an extent that by the end of the thirteenth century they had become one of the better-known business families in the city. Even so, the Medici were not regarded as one of the leading families, who were all either noble landowners or well-established merchants. Then in 1296 Ardingo de’ Medici became the first member of the family to be chosen as gonfaloniere.

Florence was an independent republic, theoretically run on democratic lines. It was ruled by a nine-man council known as the Signoria, the chief of whom was the gonfaloniere, who presided for a period of two months. The gonfaloniere and his Signoria were selected by lottery from amongst members of the guilds. These lotteries were increasingly fixed, so that the Signoria generally represented whichever leading family, or families, held sway at the time. In 1299 Guccio de’ Medici was the second member of the family to become gonfaloniere. Guccio must have shown his benefactors that the Medici could be relied upon, for in 1314 Averardo de’ Medici became the third Medici Gonfaloniere.

Florence may have been lacking in power and historical greatness, compared with such cities as Paris and Milan, but it soon made up for this in the creation of wealth. This was mainly due to the new growth industry of the thirteenth-century – banking, which was to a large extent an Italian invention. (The English term derives from the Italian word banco, referring to the original counters on which the bankers conducted their trade.) At this time Italy was the main economic power in Europe, with the Genoese and the Venetians controlling the import of silk and spices from the Orient. Marco Polo even records that in the last decade of the thirteenth century Genoese merchant ships were trading on the Caspian Sea; and as early as 1291 two Genoese galleys disappeared searching for a route to the Orient by way of West Africa. International trade was on the increase, despite hazardous rutted turnpikes and shipping routes raided by pirates. The overland journey from Florence across the Alps to the northern trading city of Bruges in Flanders, a distance of some 700 miles, usually took between two and three weeks. The less dangerous sea journey, via the port of Pisa and the Bay of Biscay, could take twice as long.

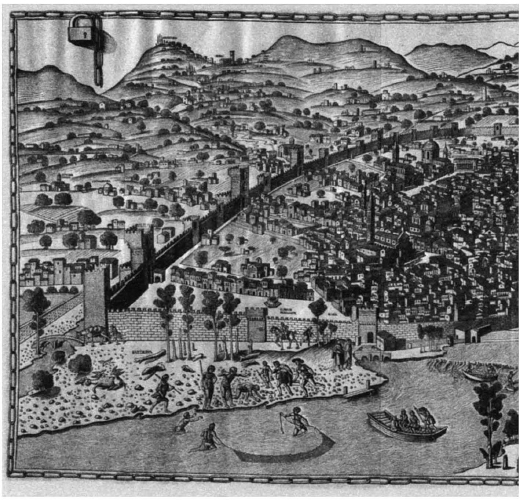

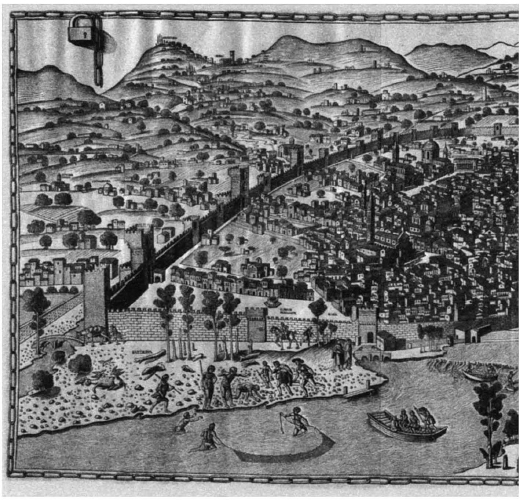

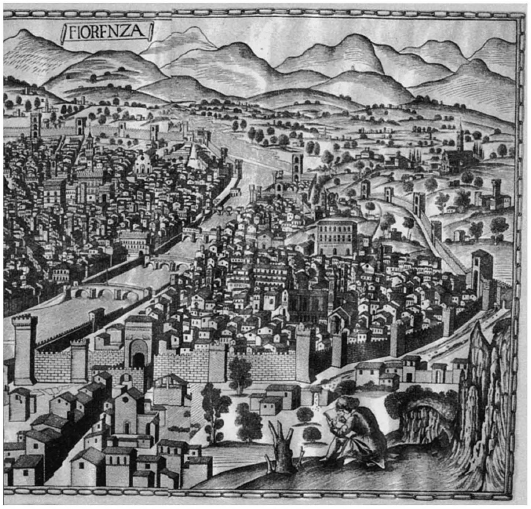

Fig 2 Florence around 1480

Goods such as cloth, wool and grain were supplemented by luxury goods from the Orient, which were mainly destined for the courts of powerful noblemen and royalty. The setting up of banks in the main trading centres greatly facilitated this burgeoning international trade, and in the process merchant bankers accumulated large assets at these centres, which they soon began loaning out at interest, despite the Church’s ban on usury. Many banks managed to circumvent the Church’s ban by maintaining that there was always a possibility of loss in their business; any extra charge was merely a payment against ‘risk’, so this was not really usury at all. Others claimed that they were not actually charging interest on their loans – any increase in the size of the repayments was due entirely to fluctuations in the exchange rate. Despite the spuriousness of its justifications, banking soon became an accepted practice.

At the end of the thirteenth century the main banking centre was Siena, the smaller city over the mountains some forty miles south of Florence; but in 1298 the leading Sienese bankers, the Bonsignori family, went bankrupt. This was largely because they had loaned huge sums to royalty and powerful courts, the main borrowers in this market, whose requests were often impossible to refuse. The difficulty was that banks simply had no power to enforce these debts: such rulers were quite literally a law unto themselves, as the Sienese bankers found to their cost. Siena never recovered from the Bonsignori collapse, and Florence quickly took over the banking trade. This was soon dominated by three leading Florentine families: the Bardi, the Peruzzi and the Acciaiuoli, which became the greatest banking houses throughout Europe, with the Peruzzi house having a network of fifteen branches, stretching from Cyprus to London.

In its early heyday one of the symbols of Florence was a lion, which occasionally appeared stamped on commemorative medals, rather than the more usual Florentine lily. This lion was to become more than a fanciful symbol, for it was during this period that the city acquired its first real lions, probably through its trading link to the Levant. The lions were kept in a large cage on the Piazza San Giovanni, close to the cathedral, and these exotic creatures were a source of wonder and pride to the citizens; their occasional roars, which resounded through the streets, became regarded as omens by the superstitious population. Some time during the mid-fourteenth century the lions were moved to a site behind the Palazzo della Signoria, where their cage stood in the street still known as Via dei Leoni. Yet despite their popularity, and their central appearance in the life of the city, they were not adopted as the symbol for the city’s most successful coinage, an honour that fell to the lily.

Florence’s banking supremacy, and the trustworthiness of its bankers, led to the city’s currency becoming an institution. As early as 1252 Florence had issued the fiorino d’oro, containing fifty-four grains of gold, which became known as the florin. Owing to its unchanging gold content (a rarity in coins of the period), and its use by Florentine bankers, the florin became accepted during the fourteenth century as a standard currency throughout Europe. This was a considerable advantage to bankers, who otherwise had to deal with flexible exchange rates between a range of different coinages.

It was during this period that the foundations of modern capitalism were laid, business practice was established, and banking evolved many of its skills. Double-entry bookkeeping was invented (first appearing in 1340); fiduciary money (that is, credit based on trust, and not matched by assets) was conjured up out of nothing; and payment by ledger transfers and bills of exchange was developed. Despite these advances, the Florentine bankers soon repeated the Sienese mistake, by opening loan accounts for King Robert of Naples and Edward III of England. In 1340 Europe suffered an economic depression, and the kings who were unable to repay their debts simply reneged on them. By this stage Edward III had embarked on what would come to be known as the Hundred Years War against France, and it was reckoned that he owed the Peruzzi bank ‘the value of a realm’. As a result, the three leading banking families in Florence went bankrupt in quick succession.

Even before this catastrophe, the early fourteenth century had seen volatile times in the Florentine Republic, with political power frequently changing hands in violent fashion. The population was divided into two main parties, the Guelfs and the Ghibellines, and there were of course factions within these two parties. The Ghibellines drew their support mainly from the noble families, while the Guelfs were supported by the wealthy merchants and the popolo minuto, meaning ‘the small people’ – that is, the general public or working class. (Besides being disparaging, the term popolo minuto also contained an element of truth, mainly because the poorer classes endured a severely reduced diet, which restricted their growth: the popolo minuto were literally small people.)

Despite such political instability, the early fourteenth century saw Florence’s first cultural golden age, with the city producing three of Italy’s finest writers – Dante, Boccaccio and Petrarch – in just half a century. In a break with clerical tradition, they chose to write in Tuscan rather than Latin, and this not only established the Tuscan dialect as the standard form of Italian, but introduced a secular humanist element by dispersing literature beyond the language of the Church. This secular humanism was also reflected in the interests pursued by these authors. Petrarch, for instance, would become renowned for seeking out the manuscripts of ancient classical authors, which had long lain forgotten in monasteries throughout Europe. Boccaccio, on the other hand, would become notorious for his Decameron, a sequence of sometimes obscene and often humorous tales depicting life as it was actually lived amongst the people of the time, rather than the way the authorities (particularly the Church) considered it ought to be lived. The two finest artists of the period, Giotto and Pisano, also lived in Florence and showed humanist inclinations, with their figures breaking away from the medieval formalism of the day to assume a more modern, lifelike manner with recognisable expressions of emotion. Such luminaries brought Florentine culture to the brink of the Renaissance; but before this could develop further, Europe was struck by the greatest disaster in its history.

The economic depression of the early 1340s was followed by the catastrophe of the Black Death. This arrived in Europe from China, by way of Genoese ships from the Black Sea, in 1347. Contemporary chroniclers, confirmed by recent research, record that during the next four years around one-third of Europe’s population was wiped out by the plague. Owing to bad sanitation and ignorance of how the disease spread, the situation was worst in the cities, where families suspected of having the plague were sometimes simply bricked up in their homes and left to die. Those who could afford to do so fled from Florence into the surrounding Tuscan countryside; of those who remained behind, well over half perished. Not surprisingly, the first stirrings of the new humanism were quickly replaced by superstitious morbidity; yet the comparative social stasis of medieval Europe had begun to crumble, and fundamental change was inevitable.

The Medici family in Florence had by now expanded to include some twenty or thirty nuclear families. The affiliation of these families, recognisable by name, would have been looser than that of a single family, more akin to that of a clan, with its own internal rivalries but overall group loyalty. The Medici appear to have taken advantage of the vacuum left by the bankruptcy of the three leading Florentine banking families, with several Medici going into banking, establishing their own separate small enterprises. Brothers or cousins would have joined together as partners to provide shares of the original capital, often working together in the daily running of the bank, which would have involved such business as foreign-currency exchange, small deposits, and seasonal loans to wool traders, weavers and the like. At least two of these enterprises were sufficiently canny, or lucky, to survive the economic ravages of the Black Death, and were thus able to consolidate the Medici power base. The Medici now provided the city with more than the occasional gonfaloniere. Giovanni de’ Medici (a direct descendant of the first-documented Chiarissimo) departed from the usual Medici preserve of civil affairs, and became a military leader. Keen to demonstrate his prowess, in 1343 he encouraged the Florentines into a war against the small city state of Lucca, some forty miles to the west. Giovanni tried to take Lucca, failed, then laid siege to the town; but the campaign turned into a fiasco, and on his return to Florence Giovanni was executed. After this, the Medicis stuck to civil affairs – yet on occasion these could prove just as dangerous.

In 1378 Giovanni’s cousin Salvestro de’ Medici became gonfaloniere, and during his two-month period in office a revolt broke out amongst the wool-workers, who were known as the ciompi (after the sound that their distinctive wooden clogs made on the stone-slabbed streets). The ciompi revolt was ostensibly led by Michele di Lando, who fronted a mob of fellow wool-workers and artisans demanding the right to form their own guilds – and thus the right to vote, and at least theoretically have a chance of getting onto the ruling Signoria. Despite being gonfaloniere, Salvestro sympathised with the revolt, though it appears that he also saw it as an opportunity to advance the Medici cause. In order to stir up trouble and intimidate the noble faction that had balked the Medicis, Salvestro secretly threw open the prisons. What had begun as a protest quickly became a riot, with Salvestro and the other eight members of the Signoria forced to barricade themselves in the Palazzo della Signoria while the mob went on the rampage, looting the palaces of the nobles and merchants, setting fire to houses and roughing up members of the guilds. In a characteristic political homily, Machiavelli would later remark of these events in his History of Florence: ‘Let no one stir things up in a city, believing that he can stop them as he pleases or that he is in charge of what happens next.’

Salvestro’s house was spared, allegedly because of his sympathy with the protesters, though this caused some to believe that Salvestro may well have instigated the revolt. Even given the deviousness of Florentine politics, this seems unlikely, especially in the light of what followed. In the immediate aftermath of the disturbances a commune was set up by the mob, Salvestro was deposed as gonfaloniere and the mob-leader Michele di Lando was installed in his place. Despite the continuing atmosphere of instability, this state of affairs would last for more than two years, though in time Michele di Lando found himself more and more out of his depth, and took to consulting secretly with Salvestro about what to do next. The ciompi and their supporters eventually got wind of this, and fearing an undercover return of power to the old rulers, took to the streets, threatening to destroy the city rather than let this happen. Michele di Lando panicked and turned to Salvestro de’ Medici, who proposed that they use their joint influence to call out the militia. It responded to their call, whereupon the mob backed down without a fight, dispersed and returned to their homes: the revolt was over.

The guild workers and the shopkeepers, as well as the nobles and merchants, had been horrified by the ciompi revolt; the new guilds formed by the ciompi were dissolved, and the nobles took firm control. Salvestro de’ Medici and Michele di Lando would normally have been executed, but instead they were merely exiled, in recognition of the part they had played in ending the revolt. The exile of Salvestro put paid to the bid of the Medici clan to become a leading force in Florentine politics, and was also a severe blow to the family business, which was run only with difficulty from exile.

When Salvestro died in 1388, the main Medici banking business was taken over by his cousin Vieri. The new head of the Medici firm was not interested in politics and devoted himself entirely to building up the business, opening exchange offices in Rome and Venice and conducting an export–import trade through the river port of Pisa. Vieri was the first Medici to achieve any business success that extended beyond the city itself, and according to Machiavelli: ‘All who have written about the events of this period agree, if Veri [sic] had been possessed of more ambition and less integrity, nothing could have stopped him from taking over as prince of the city.’ As Machiavelli was writing 130 years after the event, his assessments are not always to be trusted; here he was almost certainly exaggerating, in order to glorify the Medici. Even so, the political integrity of the Medici clan, and its loyalty to the constitutional government of Florence, was certainly put to the test during this time, no matter the precise extent of their potential political power. Just over a decade after the ciompi revolt there was another revolt, this time by the popolo magro, literally, ‘the lean people’ – the distinction being that they were the near-starving unskilled underclass, rather than the powerless artisans of the popolo minuto. But when the mob took to the streets, all those excluded from power joined them in voicing their grievances. The mob still remembered how the Medici family had been sympathetic to their cause, and they called on the elderly Vieri to lead them; but Vieri tactfully declined this dangerous offer. According to Machiavelli, he told the disappointed mob ‘to cheer up, for he was willing to act in their defence as long as they followed his advice’. He then led them to the Signoria, where he made an ingratiating speech to the council members. ‘He pleaded that the ignorant behaviour of the mob was none of his doing, and besides, as soon as they’d come to him he’d brought them straight here, before the forces of law and order.’ Miraculously, everyone concerned appeared satisfied with this performance: the revolutionaries dispersed, while the Signoria accepted Vieri’s word, allowing him to return home, and there were no reprisals. Yet despite Vieri’s skilful handling of this affair, the strain of it all had evidently been too much for him, because later that same year he died; and with Vieri the senior line of the Medici family vanished from history.