FERDINANDO II WAS succeeded in 1670 by his twenty-eight-year-old son, who became Grand Duke Cosimo III. His reign would be distinguished only by its longevity – lasting for fifty-three years, longer than that of any other Medici – though during this period little of historical import would take place, other than the long, slow and occasionally pitiful decline of both Tuscany and its ruler. Cosimo III had been the second son, and would probably have been better off following the usual course for Medici second sons into the Church; but his elder brother had died at birth, and as a result Cosimo had become the unsuitable heir.

All who met the young Cosimo stressed his gloom and piety; indeed, the ambassador from Lucca went so far as to claim that the grand duke was ‘never seen to smile’. His dominating mother Vittoria encouraged his religiosity, which appears to have been more a psychological ailment than genuine spirituality. All Cosimo spoke about was martyrs and salvation; all he read was theology and descriptions of miracles, all he seemed to do was attend daily Mass and go on pilgrimages to shrines around the countryside. By the time he was nineteen, even his unassertive father realised that something had to be done – the obvious answer was to get him married.

Ferdinando II began making enquiries, and finally managed to arrange a highly advantageous marriage to a niece of King Louis XIII of France. The separate French and Italian blood lines of the Medici were now becoming worryingly close: Ferdinando I’s French wife Christina had been a granddaughter of Catherine de Médicis; and now Ferdinando I’s great-grandson was marrying a granddaughter of Marie de Medicis, who had been Catherine de Médias’ distant cousin. Other Medici had already married into the great royal houses of Europe – the Habsburgs, as well as the Valois and the Bourbons (both of France). These too had many intermarriages, and the shadow of inbreeding hung heavily over all such families who wished to preserve their high pedigree by marrying only royalty, which frequently meant marrying amongst themselves. Madness, degeneracy and odd physical features (such as the notorious Habsburg chin, where the lower teeth overlapped those of the upper jaw) were now becoming a recurrent feature of all European royal families, and of lesser, often related families, such as the Italian grand-ducal branch of the Medici who wished to marry into them. In aspiring to greatness of lineage, the Medici were playing a dangerous game.

Cosimo’s bride-to-be was Marguérite-Louise of Orléans, daughter of Gaston, Duke of Orleans, and the marriage was arranged through Cardinal Mazarin, chief adviser to the French king Louis XIV (who had succeeded in 1643, on the death of his father Louis XIII, son of Marie de Médicis). Cardinal Mazarin had an ambition to be pope, and had quietly informed Ferdinando II that the price for this marriage was Medici support for his candidacy when the occasion arose.

Word reached Florence that the fifteen-year-old Marguérite-Louise had ‘brown hair, greenish-blue eyes, and a sweet, gentle temperament’. As regards her temperament, nothing could have been further from the truth. Marguérite-Louise was a wilful, utterly spoilt teenager, who was used to having her own freedom and getting her own way. By this stage she had become infatuated with her eighteen-year-old cousin Charles of Lorraine and wished to marry him. Even Marguérite-Louise’s mother, the Duchess of Orléans, was against her daughter marrying a distant, unseen Italian, but Cardinal Mazarin bribed her to support his case.

The marriage contract was signed in January 1661, with a proxy marriage ceremony due to take place in April of that year. Arranged royal marriages of the period were the reverse of modern practice, and must have involved some peculiar psychological procedures at the best of times; following her proxy marriage, Marguérite-Louise would be expected to depart for Italy to meet her unknown bridegroom, take up married life, and only then get to know him.

From the start Marguérite-Louise put up spirited opposition to her arranged marriage. Then in March 1661 Cardinal Mazarin died, whereupon the Duchess of Orléans immediately petitioned the king to call off the marriage. But Louis XIV would not hear of this, so Marguerite-Louise went to see the king herself; kneeling before Louis XIV, she begged him forcefully not to make her marry Cosimo de’ Medici, However, the king remained adamant, the proxy marriage was ‘celebrated’ in the Louvre and Marguerite-Louise departed for Florence, ‘weeping openly for all to see’. It was a hard fate for a fifteen-year-old girl, made even harder by her obdurate character. She cheered up briefly when she arrived in Marseilles, where Charles of Lorraine came unexpectedly to bid her farewell, but in the end this only made matters worse. When Marguérite-Louise embarked on the galley decked with garlands and coloured ribbons, which was to row her to Livorno, it must have seemed like a fairy tale without a happy ending.

Back in Florence, Ferdinando II had been pleased to notice certain changes in his son’s demeanour. Cosimo started taking care about his appearance, and even began dressing in the French syle, preparing to make a good impression on his French bride. Yet beneath this uncharacteristically fashionable attire, it was all too plain that Cosimo remained a fat and gloomy nineteen-year-old, with heavy-lidded Medici eyes and bulbous lips.

The young married couple set eyes on each other for the first time on 15 June at the Villa Ambrogiana, the Medici hunting lodge near Empoli, just fifteen miles from Florence. It was an inauspicious meeting; Marguérite-Louise was morose, which proved a discouragement to Cosimo, who could not even be induced to kiss the bride. Despite the unprepossessing character of both the bride and the groom, it is hard not to feel sympathy for them both in this impossible situation (which would have had its echoes in every family of consequence throughout western Europe).

Such were the two figures who would star in one of the most glorious celebrations that Florence had ever witnessed. The festivities commenced five days later, in a city whose every street had been transformed for the occasion; not since the entry of Pope Leo X, a century and a half previously, had Florence been so decorated. The Piazza San Gallo was lined with banks of seats, and triumphal arches bordered the route to the cathedral. Preceded by columns of Swiss Guards, Cosimo rode into the piazza resplendent in a black tunic laced with glinting diamonds, accompanied by 100 men-at-arms all dressed in the Medici colours. Following him, reclining in an open carriage drawn by white mules, came Marguerite-Louise, wearing a wedding gown of embroidered silver cloth overlain with ‘a chain of diamonds, and forty tapering pearls hanging between them, the whole attached to the shoulders by two pearls the size of a small pigeon’s egg’. Shielding her from the sun was a large gold canopy fringed with more pearls, held aloft by thirty-two young scions drawn from all the ancient families of Florence. The procession was followed by no fewer than 300 carriages, containing the remaining members of the city’s ancient families. The bride and groom dismounted and proceeded towards the cathedral, and at the entrance they were sprinkled with holy water by the Bishop of Fiesole, as twelve massed choirs sang out the Te Deum. In the midst of it all, the bridegroom’s face was fat and expressionless, his bride unable even to raise a smile.

After the ceremony the citizens of Florence celebrated as only they knew how, and the festivities would continue intermittently throughout the summer. Chariot races at the Piazza Santa Maria Novella were followed by jousting tournaments in the Piazza Santa Croce; horseraces preceded nights of fireworks; and in between there were costume balls at the Pitti Palace on such themes as historic heroes and ancient Greek legends. Even Marguerite-Louise appeared impressed by the sumptuous masque performed before 20,000 spectators in the amphitheatre of the Boboli Gardens, where tableaux enacted historical events, ballet dancers performed on horseback, and finally Cosimo himself appeared in bejewelled armour as the figure of Hercules. Yet no sooner were the celebrations over than Marguerite-Louise sank into an increasingly sullen depression, and Cosimo retreated into his customary pious gloom. Gossip amongst the palace servants was that the bride and groom were so averse to each other that they could not even bring themselves to consummate the marriage. Yet this must eventually have proved untrue, for after two years of marriage Marguerite-Louise finally gave birth to a son, Ferdinando, in August 1663.

By now the marriage was all but over. Marguerite-Louise did all within her power to antagonise and embarrass Cosimo, while for his part Cosimo withdrew into the consolation of prayer. When on one occasion he approached his wife’s bed, she snatched a bottle from her bedside table and threatened to break it over his skull if he did not leave her chamber. Marguérite-Louise surrounded herself with her French servants, moving her residence from chamber to chamber in the vast palace so that her husband could not find her. Early on, she browbeat him into giving her the Medici crown jewels, which she immediately ordered her servants to take back to France. (Ferdinando II managed to have the servants intercepted before they reached the coast.) After the birth of her child, Marguerite-Louise began writing a stream of letters to Louis XIV, begging him to arrange for the pope to annul the marriage. Louis XIV ignored her pleas, ordering her to cease writing such letters; so instead she wrote to Charles of Lorraine saying how much she loved him, imploring him to come and visit her. In the end he relented and paid a brief visit to Florence, but nothing came of this and a further stream of love letters followed him back to France. Ferdinando II then got wind of what was happening and had her letters intercepted. Early in 1667 it became clear that Marguerite-Louise was pregnant for a second time, whereupon she took to setting off on long gallops in the hope of inducing a miscarriage. This was to no avail, and in August 1667 she gave birth to a daughter, Anna Maria Luisa.

Still the misery continued: Marguerite-Louise ranged between violent anger and comatose despair, while Cosimo sank into a state of almost permanent holy depression, and the only enjoyment he appeared to gain was from eating extensive meals. Ferdinando II began to find his son’s marriage intolerable, and in pursuance of his wish for a quiet life he suggested to Cosimo that he set off on a tour of Europe – alone. Besides providing an escape from his domestic difficulties, this would also enable Cosimo to make useful diplomatic contacts in preparation for when he succeeded to the grand duchy.

In 1668 Cosimo set off on an extended summer tour of Austria, Germany and the Netherlands, but when he returned home matters remained just as before. So the next year Ferdinando II despatched Cosimo on another tour, this time to Spain, Portugal and London. His appearance in London was noted by Samuel Pepys in his Diary, where he described Cosimo as ‘a comely black fat man in a mourning suit’. Cosimo was entertained by King Charles II, and himself entertained many members of London society at a series of lavish dinner parties, which – according to those invited – were enjoyed by all present, including the host. On his way home through France, Cosimo visited Paris, where it was noted that he ‘spoke admirably on every topic and he was well acquainted with the mode of life at all the courts of Europe’, These trips seem to have taken Cosimo out of himself, his novel surroundings causing him to forget his piety and simply enjoy himself But this carefree interlude was not to last, for shortly after he returned from his second trip his father Ferdinando II died. At twenty-eight years old, his son succeeded as Grand Duke Cosimo III.

To the surprise of the court, the new grand duke began his rule by launching into an ambitious plan to reform the grand duchy’s finances, in an attempt to revive Tuscany’s flagging economy. However, this operation soon proved more complex than expected, so Cosimo III turned to his mother Vittoria for advice. As he lost interest in the problems of his administration, the formidable Vittoria gradually took over the reins of power, and it was not long before the grand-ducal cabinet was holding its meetings in her private apartments.

In 1671 Marguérite-Louise produced a second son, who was named Gian Gastone, after his French grandfather Gaston, Duke of Orléans. A year later Marguérite-Louise wrote a letter to Cosimo: ‘I declare I can live with you no longer. I am the source of your unhappiness as you are of mine.’ She informed her husband that she had written to Louis XIV asking for permission to enter a convent in Paris.

Cosimo III was outraged by this news, and ordered the grand duchess to leave Florence forthwith. She was commanded to take up residence in the Medici villa at Poggio a Caiano, twelve miles east of the city at the foot of Monte Albano, and remain there until further notice. Making a great show of her displeasure, Marguérite-Louise set out from Florence taking with her more than 150 servants, cooks, grooms and sundry attendants. Cosimo III gave orders that his wife was not allowed to leave the villa except to take walks or rides in the grounds, when she was to be accompanied at all times by a detachment of men-at-arms.

News of this situation reached Louis XIV, who entered into correspondence with Cosimo III on this matter of his wife’s incarceration; Louis was not in the habit of allowing a cousin of the royal blood to be treated in this fashion. Eventually, in December 1674, it was decided that Marguérite-Louise should be allowed to journey back to France, where she would enter a convent at Montmartre, just north of Paris. This plan appeared to suit everyone: Cosimo III kept his three children, as well as his pride; Louis XIV was heartily relieved; and Marguérite-Louise embarked on the monastic life after her own fashion. No sooner had she taken up residence at her convent than she wrote and attempted to take up once more with Charles of Lorraine, but she discovered that he was now happily married to someone else. So instead Marguérite-Louise instituted dancing lessons at the convent, and ‘indoor games’ involving the guardsmen who had been set to watch over her. Occasionally, dressed in a blonde wig with her cheeks heavily rouged, she would set off for Versailles, where she enjoyed herself gambling. When she had lost all her regular allowance from Cosimo III, she would write to him for more, interspersing her demands with such endearments as: ‘There is not an hour or a day when I do not wish someone would hang you.’ Eventually the abbess of the convent could endure Marguérite-Louise’s behaviour no longer and complained to her superiors. Marguérite-Louise responded by threatening to burn down the convent, whereupon Louis XIV arranged for her to be moved to the smaller convent of Saint-Mandé, east of Paris. Here, at the age of fifty-one, Marguérite-Louise learned to her delight that she had inherited a small fortune from a distant cousin. The mother superior of Saint-Mandé, who enjoyed dressing as a man on trips outside the walls, eventually absconded; whereupon Marguérite-Louise took over, running the convent as she saw fit. Her fiery temper began to mellow in her later years, and as mother superior she settled down to a life of quiet domesticity with a renegade priest and her community of frequently absconding nuns. In old age she would enjoy reminiscing about her glorious years as Grand Duchess of Tuscany, before she finally died in 1721 at the age of seventy-six.

No sooner had Marguérite-Louise departed in 1675 to begin her monastic life in Paris than Cosimo III found that he began to miss his wife. Despite the fact that his domestic loneliness was punctuated by letters from her heartily wishing him dead, something within him remained inconsolable. He sank further into depression, comforting himself with ever larger meals; and as these gastronomic marathons began to develop heroic proportions, so did their main participant. Feasts would be arranged on a national theme, with attendants dressed in appropriate national costumes. Oriental nights involved robes and tarbooshes; English feasts were served by men in black leggings and wigs; and on Moorish nights, attendants were required to black their faces. Similarly there could be no skimping on the food: joints and roasted fowl had to be weighed in Cosimo III’s presence before they were allowed to grace the table, and those that failed to pass the test of the scales were despatched back to the kitchens. Ice creams were sculpted into swans or boats, jellies came in the form of fortresses, their battlements cleverly incorporating exotic fruits such as pineapples. Cosimo III’s particular favourite was crystallised fruits, a delicacy that he had encountered in London, and one of his cooks was despatched to England to discover the secret of manufacturing this delight.

Such indulgence appears to have been driven by factors involving psychological displacement, rather than sheer greed, for it was not accompanied by other forms of overtly decadent behaviour or sensual licence. On the contrary, despite his increasing girth, Cosimo was a convinced – if somewhat unconvincing – puritan; he remained deeply pious and was determined that the morals of Tuscany should reflect his devout behaviour. Here he retained the domineering influence of his mother Vittoria, with the result that the fun-loving citizens of Florence, who had so enthusiastically celebrated his wedding, now began to experience a distinct chill in the city’s moral climate, which would become more extreme as Cosimo’s long reign continued.

The University of Pisa, whose scientific reputation throughout Italy was second only to that of Padua, was informed by official decree: ‘His Highness will allow no professor . . . to read or teach, in public or private, by writing or by voice, the philosophy of Democritus, or of atoms, or any saving that of Aristotle.’ There was no avoiding this educational censorship, for at the same time a decree was issued forbidding citizens of Tuscany from attending any university beyond its borders, while philosophers and intellectuals who disobeyed this decree were liable to punitive fines or even imprisonment. Gone were the days when the Medici were the patrons of poets and scientists; Florence, once one of the great intellectual and cultural centres of Europe, now sank into repression and ignorance.

Such decrees defended the moral teachings of religion; and further decrees would safeguard its moral practices. The annual May Festival was banned because of its pagan origins, and girls were forbidden to sing the joyous songs of May in the streets, on pain of whipping. The practice of young men calling up to young women leaning from the windows, a long-established exercise in flirtation and courtship, was also forbidden because ‘it led to rape and abortion.’ There was even a futile attempt to revive the canon law that forbade actresses. Likewise, it was found impossible to banish prostitution, but from now on this practice was strictly supervised. All prostitutes had to buy an annual licence costing the equivalent of six florins (at the time a month’s wage for an orthodox unskilled worker); they were also required to wear yellow ribbons in their hair and to carry a lantern in the street at night. Failure to comply would result in the offender being stripped to the waist and whipped through the streets. Those accused of sodomy were beheaded; and as Cosimo III’s reign extended from years into decades, there was an ever increasing number of public executions for all manner of offences. Even comparatively minor misdemeanours could result in the offender being sentenced to the galleys, a fate from which only a few spectral, broken figures ever returned.

As is so often the case where social purity is concerned, the new laws soon began to take on a racial element. For many years there had been prohibitions on Jews living in Florence, and these were now much more strictly enforced throughout the whole of Tuscany. Anti-Semitism became institutionalised, with Jews forbidden to marry Christians, or even to live in the same household. Jews were also forbidden to visit Christian prostitutes, and any woman found guilty of prostituting herself to a Jew was whipped before being sent to jail. The effect of these laws was most strongly felt in Livorno, where the Jewish colony had reached 22,000; many Jews began to seek refuge elsewhere, and tax revenues gathered from trade between the free port and the Tuscan hinterland slumped. In such a climate any xenophobic prejudices were given licence, and the new laws represented the tip of the iceberg where daily social intercourse was concerned, especially in such a time of general austerity and need. As a result, the thousand or so Jews, Turks and Balkan nationals remaining in Florence found themselves becoming persecuted minorities. The benign despotism of the early grand dukes now became out-and-out tyranny, and while Cosimo III glumly stuffed himself in his palace, the night streets of an impoverished Florence were dark and silent.

As the economy of the grand duchy continued to decline, Cosimo III imposed further taxes, which were required in order to support the bureacracy that continued to run the country for him. Left entirely to its own devices, this administration might well have proved the saviour of Tuscany, yet it too was affected by the heavy hand of repression; the administration was efficient, but it was not permitted to initiate the necessary reforms to revive the economy. Only the Church thrived; priests and religious institutions were for the most part exempt from tax, and Florence became ever more a city of priests and nuns. During the reign of Cosimo III the number of nuns rose to the point where they accounted for 12 per cent of the female population.

Measures taken to raise money from the few remaining lucrative elements of the commercial sector only had the effect of stifling enterprise. Merchants were sold monopolies on staple commodities such as salt, flour and olive oil, but traders were then permitted to buy an ‘exemption’, which provided limited immunity from a monopoly. Despite this, such monopolies were not taken lightly. The salt monopoly was a case in point: the extraction of salt by illegal means, such as boiling down fish brine, became a capital offence.

The small traders and craftsmen, upon whose businesses the prosperity of the grand duchy so depended, fell into decline, while in the countryside outlying fields of arable land returned to wilderness. There are no precise reliable figures, but all the indications are that the population of Tuscany as a whole may well have declined by over 40 per cent during Cosimo III’s long reign. The English Bishop of Salisbury Gilbert Burnett, travelling through Italy in 1685, noted: ‘As one goes over Tuscany, it appears so dispeopled that one cannot but wonder to find a country that hath been the scene of so much action, and so many wars, now so forsaken and poor.’

Cosimo III must also have seen this, for he too travelled about Tuscany on a regular basis, though the purpose of his tours was not to observe the state of the grand duchy. Cosimo III was a great believer in pilgrimages to the many obscure shrines dotted about the countryside, and when not engaged in such spiritually nourishing journeys, he would spend hours on his knees in the dimness of his personal chapel in the Palazzo Pitti.

Cooks were not the only members of Cosimo III’s staff who were despatched abroad on errands; he also had a team of agents who roamed Europe in search of holy relics. These were purchased with sums from the ever-decreasing exchequer; and when this became depleted, Cosimo III would make inroads into the Medici family fortune. The purchase of expensive religious knick-knacks, many of which were no longer required by Protestant states, may be seen as the last gasp of ruling Medici patronage, though such patronage at home in the old style had not yet entirely dried up. Cosimo III did indulge in direct patronage of his favourite artist, Gaetano Zumbo, a Sicilian who produced intricate lifelike works in wax depicting the sufferings of the damned in Hell, saints undergoing excruciating martyrdom, and luridly imaginative depictions of plague victims. In the same vein, Cosimo III maintained a collection of drawings depicting with great verisimilitude various freaks of nature, including doubleheaded calves and dogs, misshapen dwarfs, as well as imaginative drawings of exotic creatures and medical drawings of diseases. These last catered to his increasing tendency to hypochondria, which he nursed with pampering cures and obscure elixirs. Fortunately these did not affect his physical health, which was remarkably robust, given his overweight frame and unhealthy lifestyle; his mind, on the other hand, was said to have become increasingly obsessed with a fear of death.

It had taken the Medici just over two and a half centuries to reach this pitiful state of decline. Compare this state of affairs with that which had prevailed during the time of Cosimo III’s original namesake, Cosimo Pater Patriae. This first Medici ruler of Florence was racked by painful and debilitating illness, and lived in fear of hellfire for disobeying the Bible’s prohibition of usury. Yet his fear of death and damnation had produced churches and orphanages, libraries filled with ancient learning, many pioneer scholars of humanism and masterpieces of early Renaissance art.

In 1694 Cosimo III’s formidable and pious mother Vittoria finally died, leaving her son with the prospect of running the grand duchy on his own. He now had to take at least a passing interest in the affairs of state; the administration may have virtually run itself, but foreign policy required decisions that lay beyond the scope of the bureaucracy. Here Cosimo III proved unexpectedly adroit in following the policy of inert neutrality maintained by his father Ferdinando II, and the continuance of this policy meant that Tuscany was now largely disregarded on the international scene. Formerly courted (and threatened) by kings of France and Naples, consulted (and coerced) by Holy Roman Emperors and popes, the ruler of Tuscany was now considered an irrelevance. Fortunately his territory was also disregarded, which meant that Tuscany was not involved in such major upheavals as the War of the Spanish Succession, which lasted from 1701 to 1714, during which northern Europe was torn apart as the French, the English and the Dutch Republic fought over the German, Spanish and Austrian territories of the Holy Roman Empire. In Italy, Savoy and Naples became involved, but Cosimo III did nothing to jeopardise the fate of Tuscany, largely by doing nothing.

Neutrality was not only wise for Tuscany, it was also a necessity, for during these years the grand duchy would have been incapable of military action. A glance at the detailed military records kept by the ever-efficient bureaucracy is revealing. The garrison at Livorno is listed as containing 1,700 men, though closer inspection reveals that many of the soldiers on the payroll were more than seventy years old, some even more than eighty. Descriptions of their able-bodied readiness descends into farce, with such entries as ‘has lost his sight’ and ‘does not see owing to advanced age and walks with a stick’. As for the once-great Tuscan navy, this was reduced to three galleys and a few support craft, manned by a company of just 198 men.

However, Cosimo III’s policy was never entirely neutral. With suitable diplomatic secrecy, during the early years of his rule he began a covert but persistent correspondence with the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, who was by now ill and ageing. Leopold I’s long reign was degenerating into the struggles that presaged the War of the Spanish Succession, but Cosimo III was more interested in another matter. He was insistent that the Grand Dukes of Tuscany should be promoted to royal status, so that instead of being addressed as ‘Your Highness’, Cosimo III could be addressed as ‘Your Royal Highness’. In order to terminate this seemingly interminable correspondence, Leopold I finally agreed to license this ‘trattamento real’ (treatment as royalty) for the Grand Dukes of Tuscany in 1691. Armed with this pedigree, Cosimo III could now concentrate on the problem of the Medici succession. This involved trying to marry his offspring into European royalty so that they could produce male heirs, though this proved a somewhat difficult task, largely owing to the genetic heritage at his disposal.

At first glance, Cosimo III’s eldest son Ferdinando seemed promising dynastic material. Despite having his early childhood disrupted by the wilful and unpredictable behaviour of his mother Marguerite-Louise, he had grown into a young man of high intelligence who was also a genuine connoisseur of art, becoming arguably the most discerning of all the great Medici collectors of paintings. The previous great Medici collectors had always used patronage for a purpose: as a means of political aggrandisement and control, as a salve to their conscience or to win friendship. There had invariably been an ultra-artistic motive in the commissioning of an artist. Ferdinando, on the other hand, collected paintings purely because they appealed to his taste, though unfortunately the art, the artists and the funds available to him were all of a lesser magnitude than those of his predecessors. As a result, the collections in his apartments at the Palazzo Pitti and the Medici residence at Poggio a Caiano consisted of exquisite minor masterworks – rather than, say, the self-glorifying bravura of the Botticellis inspired by Lorenzo the Magnificent and his court. Ferdinando’s collecting would remain a triumph of pure taste, rather than an expression of political patronage.

Ferdinando also played a considerable role in the musical flowering that took place during this period – an event that can be seen as a direct cultural consequence of the earlier renaissance in other arts. Ferdinando’s most renowned achievement in this field was the close association he formed with the Sicilian-born operatic composer Alessandro Scarlatti. Since its birth in Florence over a century and a half previously, opera had spread far beyond Italy to the courts of Louis XIV in France and the new Holy Roman Emperor, Joseph I, in Vienna. But Italian opera remained supreme, especially in Venice and Naples. Scarlatti was the leading practitioner of his time, extending opera beyond its early Baroque manifestation into the new musical era now known as Pre-classical. He gave a form to opera, making it revolve around recitative and arias, during which the drama stopped while the singer gave operatic vent to his emotions, often at some length. This ushered in the era of the virtuoso leading singers, with the female roles usually sung by castrati. In character and role, these were the first prima donnas – to such an extent that they soon succeeded in appropriating most of the leading male roles!

In 1702 Ferdinando invited Scarlatti to Florence, where he composed five operas for performance in the Medici villa at Pratolino (where Galileo had once tutored the young Cosimo II). These operas were highly regarded at the time, though all but fragments of them are now lost. After two years Scarlatti moved on to Rome and then Venice, but he corresponded regularly with Ferdinando over the next decade or so, to such an extent that these letters are now the main source for Scarlatti’s life during this period.

As a young man, Ferdinando had soon become aware of his father’s lack of interest in the governance of the grand duchy, but when he approached Cosimo III in the hope of taking on some of these duties, he was firmly rebuffed. This produced a predictable psychological reaction, and from then on the capable and intelligent son did all he could to outrage his doltish, bigoted father. Unfortunately this involved increasingly self-destructive behaviour, and what had begun as wilful rebellion quickly degenerated into a roistering dissipation to which his Medici temperament proved all too enthusiastically suited. Ferdinando took himself off to Venice, where there was more scope for such behaviour, and returned some time later with an arrogant castrato opera singer called Cecchino in tow.

After the joys of Venice, Florence proved a distressing anticlimax; the streets were filled with sanctimonious priests and nuns, whilst every corner had its wretched beggar. In an effort to liven things up (and further outrage his father), Ferdinando organised a great jousting contest for the pre-Lenten carnival of 1689, which took place before an enthusiastic crowd in the Piazza Santa Croce. The theme of the joust was a battle between Europe and Asia, and with a burst of energy and organisation worthy of Lorenzo the Magnificent himself, Ferdinando produced two teams of exotic jousters. One was dressed as Eastern warriors, with some members even in authentic armour captured from campaigns against the Ottomans; the other team was outfitted as European knights. Was this perhaps a sign of things to come, when Ferdinando succeeded as grand duke? Or would it prove just a final flourish of the old Medici ways?

Ferdinando continued in his erratic behaviour. One moment he would be corresponding with the German composer Handel, trying to persuade him to visit Florence, or involved in efforts to save a decaying Raphael altarpiece from one of the city’s churches; the next he would be setting off with Cecchino for a further bout of debauchery in the fleshpots of Venice, where he contracted syphilis, allegedly from Cecchino. Undeterred, Cosimo III doggedly continued with his enquiries around the courts of Europe in search of a prestigious wife for his son, one who would produce further male heirs to ensure the continuance of the Medici dynasty. Eventually he managed to secure Princess Violante of Bavaria, who on her arrival in Florence turned out to be a dull and rather intimidated sixteen-year-old girl. At Cosimo III’s insistence she was married to Ferdinando nonetheless, though by now Ferdinando’s dissipated behaviour and homosexual inclinations made it almost certain that he would prove incapable of producing an heir.

When Cosimo III realised that his obsession with male heirs had probably been thwarted in this direction, he turned his attentions to his second child, his daughter Anna Maria Luisa, a tall, bony, rather masculine and awkward girl with long black hair. Approaches for a suitable husband were made to a string of royal families. The Spanish were not interested, nor were the Portugese; the French and the House of Savoy politely but firmly turned him down; and he was then rebuffed by the Spanish (again). Finally Cosimo had success in Germany, managing to secure Johann Wilhelm, the elector palatine, as a prestigous bridegroom; though it turned out that he had syphilis, and as a result Anna Maria Luisa would produce only a series of miscarriages.

With increasing urgency, Cosimo III turned his attentions to his final child, his second son Gian Gastone, an intellectually gifted, aesthetically inclined young man who preferred his own company to that of his fellow human beings. Gian Gastone was to prove even less of a catch than his elder brother; he was both obese and immoderately sensitive, and the harshness of reality had by now driven this touchy colossus to drink. His positive abhorrence of female company soon made it clear that he was also homosexual. Even these hindrances might just have been overcome, if Cosimo III’s choice of a bride for his thin-skinned offspring had not been so disastrous.

Princess Anna Maria Francesca of Saxe-Lauenburg, who had recently been widowed by the death of Count Palatine Philip of Neuberg, was considered a great catch by Cosimo III. She brought with her further titles, and her claim to the Saxon electorate through her dead father meant that her husband might one day become a prince of the Holy Roman Empire. On the other hand, Anna Maria Francesca of Saxe-Lauenburg was described as being ‘of enormous weight, immense self-will and no personal attractions’. Her overbearing behaviour was said to have driven her husband to drink himself to death after just three years of marriage. In contrast to her aesthete husband-to-be, Anna Maria Francesca was uneducated, wifully philistine in her attitudes, and enjoyed rural life. According to the near-contemporary Medici historian Jacopo Galluzzi: ‘Her favoured forms of exercise had long been riding, hunting and conversing with her horses in her stables.’

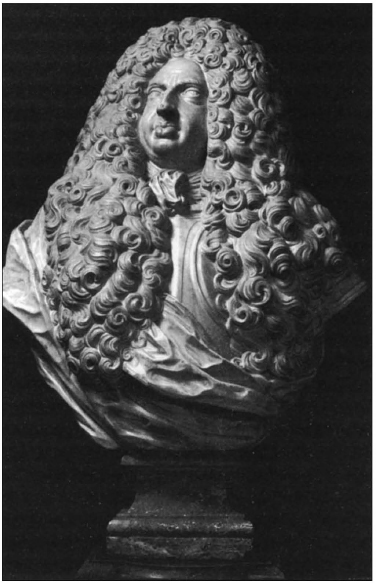

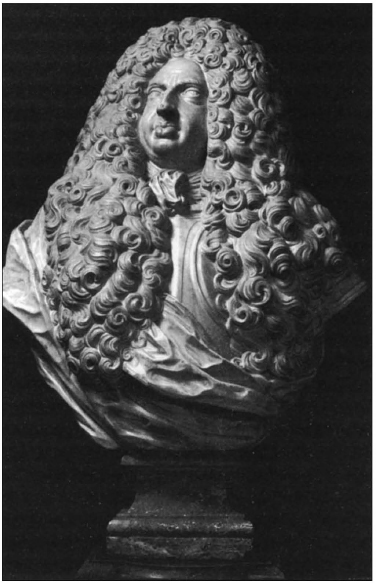

Fig 20 Gian Gastone de’ Medici

The merest rumours concerning his future bride were enough to drive Gian Gastone into a fit of trepidation, but his father was adamant that the wedding should proceed. Dejectedly and resignedly Gian Gastone made his way north across the Alps to marry his dynastically endowed German bride. On his arrival at Düsseldorf he was taken aback to find that his future wife was as fat as he was; and in her own way, she was also just as physically unappealing. Yet where Gian Gastone was simply unattractive, his bride was formidably ugly; apart from their mutual physical monstrosity, it soon became clear that neither had anything whatsoever in common.

In July 1697 the ill-matched couple were married by the Bishop of Osnabrück in the chapel of the elector’s palace at Düsseldorf; both were said to be twenty-five years old, though the formidable bride looked somewhat older. The wedding celebrations included a lengthy programme of peasant dancing; the rural attire, clashing music and raucous tenor of this entertainment proved excruciating to Gian Gastone’s classically attuned ears, though his wife applauded boisterously.

The bride insisted on leaving Düsseldorf as soon as the wedding celebrations were over, informing her husband that she could not abide urban living or sophisticated company of any sort. Gian Gastone accompanied his new bride in the royal coach down the long rutted highway across Bavaria, through the Bohemian Woods to Prague and on to the village of Reichstadt, where above the hovels and crooked rooftops rose the gloomy battlements of the bride’s ramshackle castle. Pleased to be home, Anna Maria Francesca quickly disappeared to the stables, which seemed far better equipped than the damp and chilly human living quarters, where the bridegroom was left to his own dispirited devices. It soon became clear that there was no prospect of any offspring, male or otherwise. Anna Maria Francesca renewed her interrupted equine dialogues, and Gian Gastone began dolefully consoling himself with an Italian groom called Giuliano Dami. After a while he and Giuliano began making occasional sorties into Prague, where they would enjoy the low life. According to a contemporary memoir: ‘There was also no small number of palaces at Prague belonging to great and opulent nobles. These had regiments of retainers about them in their households, footmen and lackeys of low birth and humble station. Giuliano induced His Highness to seek his diversions with these, and to mingle freely in their midst, so as to choose any specimen that appealed to his singular sense.’

In time, Gian Gastone became bolder, on one occasion even taking a trip to Paris. When Cosimo III got to hear of this he was deeply vexed, and wrote a letter to Gian Gastone bemoaning his lack of attention to producing an heir and upbraiding his son for his impious behaviour. By now Cosimo III had become even more devout and austere, and he had learned to moderate his eating habits. According to the English traveller Edward Wright, who stayed in Florence: ‘For the last twenty years of his life, his constant beverage was water. His food was plain: he ate but one dish, and always alone, except upon the festivals of St John, and other peculiar days, when his family were summoned to join him.’

Florence was undergoing a similar austerity. The population of the city had now declined by 50 per cent and was down to around 42,000. Weeds grew up between the stones in the back alleys, and houses lay derelict, fallen in on themselves. The slump in Florence’s fortunes affected all levels of society; beggars did their best to live off the tourists, meanwhile the great families were reduced to camping out in their empty palazzi, collecting their meals from local taverns. Their dismissed cooks and servants hung about the gateways of the palazzi that had formerly employed them, indicating the quality of people for whom they had once worked and the fact that they were for hire. During cold winters and times of sparse harvest, groups would gather beneath the windows of the Palazzo Pitti, calling pitifully for bread. Cosimo III would retire to his personal chapel to pray for them, while the palace guards chased them away. By 1705 the Tuscan exchequer was to all intents and purposes bankrupt.

News of this state of affairs soon began to circulate abroad. By now the Austrians had begun making inroads into northern Italy, staking a claim to Parma and Ferrara, and it soon became clear that the Austrian Holy Roman Emperor, Joseph I, had plans to extend his territory still further and annex Tuscany. The prospects for the continuation of Medici rule looked bleak: Cosimo III’s son and heir, Ferdinando, was by this stage in alcoholic decline, suffering alternately from delusions and amnesia, though the public remained largely unaware of this because he rose only at night and seldom went out. Likewise, it was becoming evident that Gian Gastone was simply incapable of ruling the grand duchy. The Emperor Joseph I was convinced that under Austrian rule, Tuscany could be turned into a thriving province once more, and at the same time Austria’s central European empire would benefit greatly from such a revitalised economic force.

Joseph I entered into diplomatic negotiations with the ageing Cosimo III, whose son Ferdinando had by now developed epilepsy – it was evident he would soon die. The population had placed great faith in Ferdinando, believing that his accession to power would bring about a return to better days, and to many he was seen as a ‘good Medici’. The Emperor Joseph I warned Cosimo III that Ferdinando’s death could well spark anti-Medici riots amongst the disillusioned population, and that these might even lead to the overthrow of the Medici. If Austrian troops could be garrisoned on Tuscan territory, this catastrophe could be avoided.

Cosimo III resisted this suggestion, but Joseph I now made plain his objective, informing Cosimo III that his imperial lawyers had made a study of the family trees of the major royal houses of Europe, and this had led them to conclude that Tuscany in fact belonged to the Holy Roman Empire. (One of Ferdinando II’s daughters had married Ferdinand Karl of Austria, while another had married the Duke of Parma, whose territory was now Austrian.) All of Italy was shaken by this news: spurious or not, Joseph I’s claim could lead to the entire peninsula becoming embroiled in a war, with Tuscany being ravaged in the process.

Pope Innocent XII, whose domains would have been next under threat, urgently contacted Cosimo III telling him to buy off the Emperor Joseph I. But Cosimo could only reply that he had no money; whereupon Innocent XII immediately authorised him to withdraw the clergy’s immunity from tax in Tuscany. As a result, Cosimo III was able to raise the equivalent of 150,000 florins, which was then used to buy off Joseph I, inducing him to withdraw his claim.

Even so, the Austrian occupation of Parma and Ferrara meant that Tuscany remained under threat, although by this stage Austria was not the only danger, for Tuscany was now menaced on all sides. The Tuscan navy, in its pitiful state, was incapable of defending the coast against any French invasion, and Spanish troops were garrisoned menacingly close across the border to the south. Only the prospect of Austrian troops entering Tuscany appeared to be keeping these other powers at bay. Cosimo III continued to dither, and in the end this lack of policy miraculously paid off In 1711 the Emperor Joseph I died, and this was followed by a lull in the War of the Spanish Succession and the empire’s territorial ambitions. Two years later Cosimo III’s son and heir Ferdinando died, but the expected riots did not materialise; by now the population was too cowed and dispirited even to take to the streets.

Cosimo III’s reign tottered on, and by 1720 it had lasted for fifty years. The English traveller Edward Wright described Cosimo III in the same year:

His Highness was about eighty years old: his state of health was then such as would not allow his going abroad; but whilst he could do that, he visited five or six churches every day. I was told he had a machine in his own apartment, whereon were fix’d little images in silver, of every saint in the calendar. The machine was made to turn so as still to present in front the Saint of the day; before which he continually perform’d his offices. His hours of eating and going to bed were very early, as was likewise his hour of rising.

By now Cosimo’s religious obsessions made him easy prey to his narrow minded advisers, most of whom were priests. All naked statues were removed from the streets and galleries, on the grounds that they were ‘an incitement to fornication, and even Michelangelo’s David, the great symbol of Florence, was hidden beneath tarpaulin. Cosimo III rarely ventured beyond the precincts of the Pitti Palace; though when he did, crowds of curious citizens gathered in sullen silence to catch a glimpse of their detested ruler. In September 1723 he was overcome by a curious fit of trembling whilst sitting at his desk, and this spasmodic affliction lasted for two hours, leaving him drained and filled with foreboding. By October Cosimo III was on his deathbed; and daily he prayed, beseeching God to forgive him for his sins – though he still managed to sign a decree further raising the ruined grand duchy’s income tax. On 31 October, at the age of eighty-one, he finally died – bringing to an end the longest and most ruinous Medici reign.