Art Reborn: The Egg Dome and the Human Statue

THE NEW HUMANISM that arose from the rediscovery of ancient knowledge and literature would in turn give rise to the Renaissance, which began as a ‘rebirth’ but would soon evolve an originality of its own. There is one crucial aspect that links this long and gradual process, which would come to full flowering as the fifteenth century progressed. This aspect is knowledge – the early humanists rediscovered it, and the Renaissance artists saw themselves as extending it. The most characteristic and original expression of the Renaissance would be its art, yet crucially its artists saw this activity as a form of learning; and here at least, the passage from humanism to the Renaissance is all but seamless.

The Renaissance artists would paint images of a visibly different humanity from that depicted in the religious paintings of their medieval predecessors. This was achieved by shedding previous stylisation and formalism, and although much of the medieval religious symbolism would be retained, this would increasingly be tempered by the artist imbuing his figures with an element of psychological realism. Human beings would be depicted with all the verisimilitude of a classical statue, usually placed in a recognisable landscape. Although the subjects remained for the most part religious (saints, the Madonna, biblical scenes and so forth), these holy figures were seen less as transcendental or metaphysical figures and more as they might have lived in the reality of their human lifetime. Art would become a form of learning about what a human being was, of understanding the purely human condition; this new art would seek to teach man about himself, and his world, in an almost scientific manner – indeed it would, in many ways, aspire to be a science. As we shall see, later Renaissance artists, such as Leonardo da Vinci, would even use their art to depict the secrets of nature, and of human nature – drawing the intricacies of flowing water, human anatomy, as well as imagined or invented complex mechanical objects. It is important to remember that this aspect of art as a form of knowledge was always an integral part of the new enterprise; from the outset, Renaissance artists saw themselves as discovering new truths – about art, about technique, about humanity and the world.

The first manifestations of this new artistic movement would be seen in fifteenth-century Italy, all but exclusively in Florence. Yet why did it originate here – why not Naples or Venice, Milan or Rome? All these other cities had sufficient wealth and elements of sophistication, as well as vivifying contacts with international trade, yet each had in its own way a debilitating factor that hampered the innovation, independence and breadth of outlook required to instigate such a major transformation as the Renaissance. Naples and Milan were subject to autocratic rulers; Rome remained for the most part a backward city, liable to the vagaries of different popes; whilst Venice was ruled by a stable patriciate. Florence, on the other hand, saw itself as a quasi-democratic republic, yet its arcane democratic process was unstable as well as being liable to corruption, and it may well have been this political instability that proved so conducive to innovation. The city also had a long tradition of civic patronage: successful merchants were expected to contribute to the glory of the city almost as a patriotic obligation. Partly as a result of all this, Florence had a tradition of artistic excellence going back generations – in the fourteenth century, Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio all had close links with Florence – and it still saw itself as a city of art, producing as well as attracting painters and artists who required patronage. This became a self-perpetuating process that would encourage the creative spark of rivalry and innovation, whilst in conjunction with this there was a flourishing intellectual tradition whose interest in ancient manuscripts nurtured early humanistic ideas, resulting in an intellectual cross-fertilisation whereby artists and poets mingled with the new philosophical humanists and scholars. All these factors, rather than any one particular reason, probably accounted for Florence’s unique role in the founding of the Renaissance – and unique in furthering this role would be the Medici. The vast yet discriminating patronage of the Medici family, particularly Cosimo, would play a formative part. The Florentine Renaissance would certainly have happened without the Medici, and the Medici would be just one Florentine family amongst several who contributed to this initial flowering – yet their distinctive and enlightened contribution, their particular encouragement of many of the main Renaissance artists, would leave its indelible mark. There would be an element of the Florentine Renaissance that was characteristically Medicean, and for better or worse it would arise from their role as godfathers, through several generations, of both the city and its cultural life.

The Medici were to be involved in the development of this new art from the very outset. In a telling coincidence, Giovanni di Bicci’s first participation in artistic patronage would result in what many consider to be the first great Renaissance work of art – the bronze doors for the Baptistery of San Giovanni. The commissioning of this work was inspired by an event that had taken place in recent Florentine history. In 1401 there had been an outbreak of plague in the city, causing widespread fear and consternation. Fortunately this outbreak abated almost as quickly as it had first appeared, yet memories had been stirred of the Black Death, which had struck so devastatingly just over half a century previously. As a thanks-giving to God for protecting the city from another Black Death, the Florentine authorities decided to provide some magnificent new bronze doors for the twelfth-century Baptistery of San Giovanni. This stood in the piazza in front of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, and held a particular place in the heart of all Florentines, for the Baptistery was the location where every child born in Florence was baptised.

Artists were invited to submit models of the doors for a competition, and a committee was set up to judge the winner. Giovanni di Bicci served on this committee, and it may well been his earliest taste of civic office, providing the shrewd middle-aged banker with his first experience of the world of art and patronage. The decision that the committee finally arrived at was a controversial one: the winning design was judged to have been provided by an unknown illegitimate twenty-four-year-old goldsmith called Lorenzo Ghiberti.

It would take Ghiberti more than twenty years before he was finally satisfied with the bronze doors he produced; and in order to achieve this, he would have to transform the art of bronze-casting, introducing both new methods and new apparatus. This was almost as much a feat of technology as it was a work of art. Ghiberti’s doors contained a series of biblical scenes cast in relief, depicting classically draped figures who were remarkably lifelike, enacting dramatic scenes, often against striking architectural backgrounds, such as an imposing Ancient Roman arch or Noah’s Ark depicted as a pyramid. These backgrounds, and the drapery in which many of the figures were clothed, reflected Ghiberti’s deep interest in the formerly ignored ancient ruins that were now being noticed as if for the first time, as well as his interest in the newly discovered classical learning (his depiction of Noah’s Ark as a pyramid comes from the third-century Greek theologian Origen, a description that was ignored throughout the medieval era).

Ghiberti’s Baptistery doors were received with great acclaim, and are now regarded as one of the formative works of early Renaissance art. Such was their success that Ghiberti was commissioned to design another set of doors for the eastern entrance to the Baptistery, and these would take him more than thirty years to complete, finishing in 1452 – though this was not entirely due to his perfectionism. During this period Ghiberti also accepted many commissions for other work: the Baptistery doors had made him famous, and as a result he would become one of the richest artists in the city. His later catasto tax returns show that he owned a farm outside Florence, as well as a vineyard and even a flock of sheep. His self-portrait, which he included unobtrusively in the east doors, depicts an amiable, balding man. He would take so long over these second Baptistery doors that they would only be installed in the year following his death. It was said that when the young Michelangelo first saw these doors years later, he was so overwhelmed by their beauty that he declared ‘they could be the gates of Paradise’.

Yet not all the artists of Florence were so impressed. The man who narrowly lost out to Ghiberti in 1402 had been so angry at his rejection that he had packed up and gone to live in Rome. This was the artist Filippo Brunelleschi, who had been born in Florence in 1377 and was renowned as an extremely difficult character: proud, easy to take offence, secretive and possessed of a volatile temper. One of his favoured habits was sending scurrilous and insulting anonymous verses to people he felt had somehow slighted him.

Brunelleschi felt so humiliated over his defeat by Ghiberti in the competition for the Baptistery doors that he decided to abandon fine art and become an architect; this time, he promised himself, no one would better him. He travelled to Rome with the precocious sixteen-year-old artist Donatello, who was possessed of an equally inflammable temperament, and together the two of them searched and argued their way through the ruins of Ancient Rome, unearthing statues and studying pediments. Extraordinarily, Brunelleschi never confided in Donatello that he was in fact studying to become an architect, though in the course of these explorations he would come to understand one of the greatest secrets of architectural history.

Amongst the few remaining intact classical buildings in Rome was the Pantheon, with its miraculous 142-foot-wide dome, which had been built for the Emperor Hadrian at the height of Rome’s imperial grandeur. The secret of how its dome had been constructed had long been lost, and for 1,300 years this had remained the widest dome ever erected. Brunelleschi became intrigued, and somehow contrived to climb up onto the roof of the Pantheon, where he removed some of the dome’s outer stones and discovered that it had an inner dome. This inner vaulting consisted of blocks of stone that dovetailed into one another, so that they became virtually self-supporting; at the same time, the connections between the inner and outer dome were constructed in such a way that they actually supported each other.

When Brunelleschi returned to Florence around 1417, he quickly established a name for himself as one of the city’s leading architects. As we have seen, in 1419 Giovanni di Bicci headed the committee that commissioned Brunelleschi to build the city’s foundling hospital, named in quaint euphemistic fashion Ospedale degli Innocenti. This would be Brunelleschi’s first major work, and its clean classical façade would mark a distinct contrast to the surrounding medieval buildings, incorporating as it did such rediscovered technical details as graceful supporting pillars. In the course of this work, the dry ageing banker and his temperamental architect unexpectedly formed a deep bond of friendship. From the outset, Brunelleschi had expressed very definite ideas about the type of building he wished to erect; while Giovanni for his part felt very uncertain in the novel role of patron, and took to consulting his humanist-educated son Cosimo. It required little encouragement for Cosimo to become enthusiastic about the project, and his explanation of Brunelleschi’s innovative aims soon filled Giovanni with admiration for his architect, while Cosimo’s informed understanding of Brunelleschi’s intentions meant that soon he too became a friend of Brunelleschi. The two men now managed to persuade Giovanni to branch out in his role as patron, and as a result he commissioned Brunelleschi to restore and enlarge San Lorenzo, the church of the Medici clan. Brunelleschi would eventually finish the sacristy of San Lorenzo just in time for Giovanni’s burial here in 1429 – although by this stage he had become involved in a far greater project, the one for which he will always be remembered.

The Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore had been started as long ago as 1296, when Florence’s first banking boom and its ascendancy as a centre of the wool trade had made it one of the richest cities in Europe. Filled with civic pride, the inhabitants of Florence had come to see their city as the embodiment of a new Rome. To celebrate this self-acclaimed eminence, it had been decided that the new cathedral should be one of the largest in all Christendom, a match for the great Gothic cathedrals of northern Europe, and the Byzantine Santa Sophia in Constantinople with its famous dome.

But in rapid succession Florence had been hit by the bankruptcy of the Peruzzi, Bardi and Acciaiuoli banks, followed by the Black Death, with the result that just half a century after building had begun, the new cathedral remained little more than an abandoned building site. The unfinished façade enclosed a patch of waste ground exposed to all weathers, making it look more like a ruin than a construction project, while the eastern foundations had remained exposed for so many years that the street running beside the proposed cathedral had become known as Lungo di Fondamenti (‘Along the Foundations’).

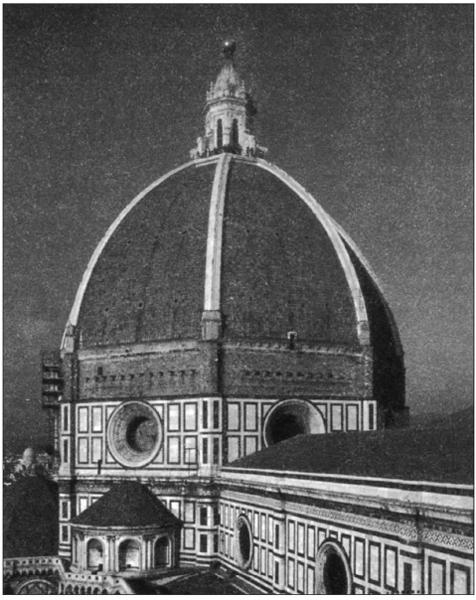

Yet prosperity had eventually returned: the European wool trade had begun to flourish again, and the second generation of Florentine banks had asserted their pre-eminence, with none throughout Europe able to match the Medici Bank. Once more work had started again on the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, and by 1418 it was ready for the construction of its great crowning dome. This brought to light a crucial problem, for according to the original model of the cathedral the dome would need to have a span of 138 feet, wider than any but the Pantheon in Rome. This dome had been intended to represent the pride and achievement of the great city of Florence, but unfortunately the ambition of its citizens had far outstripped the achievement of any contemporary architect – with the result that instead of representing the city’s pride and achievement, the impossible dome was now exposing Florence as a laughing stock.

The question remained as to how such an enormous structure could be erected without the walls of the cathedral buckling beneath the insupportable weight. At anxious meetings of the Signoria and the relevant committees, all manner of ingenious ideas were put forward. Perhaps the dome could be constructed out of a lightweight material, such as pumice stone; but then it was discovered that there simply was not enough wood available to build sufficient scaffolding. A suggested solution to this problem was that the entire inside of the cathedral should be filled with earth, so that the dome could be constructed with its stones supported from beneath. But there then remained the question of how all the earth was to be cleared from inside the completed cathedral. A proposal was made that it should be liberally mixed with small coins, which would encourage the poor, and small boys, to carry it out for free! The committee despaired, and as a final resort a prize competition was announced.

Brunelleschi entered the contest, proposing an egg-shaped dome supported by stone ribs, and out of the eleven submitted entries his was judged to be the best. But before awarding him the project, the judges wanted to be sure he was able to complete the task, and demanded to know exactly how he planned to construct his dome. Brunelleschi adamantly refused to reveal his secret, and in answer to the committee’s persisting demands he proposed a question of his own: producing an egg from his pocket, he asked the committee if any of them could tell him how to make it stand on its end. When no one could answer this, Brunelleschi banged the upright egg sharply on the table so that it cracked open, but remained upright. The committee immediately protested that any of them could have done this, but Brunelleschi replied: ‘Yes, and you would say just the same if I told you how I intended to build the dome.’

The committee remained wary. Eventually they awarded him the project, but in order to safeguard themselves they insisted on one condition – Brunelleschi would have to take on a partner to assist him in this project. The partner whom the committee chose was Ghiberti, and when Brunelleschi heard that he would be expected to work alongside his great rival, he was beside himself with rage, so much so that the committee was forced to call the palace guard to have him forcibly removed and thrown out into the piazza. Yet in the end, by sheer persistence and obstinacy, Brunelleschi got his way. Even so, he would remain as suspicious as ever: from now on he would jealously guard the secrets of his construction methods, labelling his plans with cryptic symbols, using his own cipher of Arabic numerals for the calculations. Not only were his methods secret, but many of them had never been tried before; the risk was enormous, and even Brunelleschi himself was not sure they would work. He decided to build the dome without erecting any supporting scaffolding, devising instead a method by which its arching stones supported themselves during its construction. The secret of his method was adapted from the Pantheon in Rome: he built two domes, one within the other, each in its own way supporting the other, with the bricks of the inner dome laid in an interlocking self-supporting herringbone pattern. Yet these techniques were much more than mere copies; the Romans may have left their dome, but they had left no instructions telling how they had built it. This meant that when it came to the actual details of construction, Brunelleschi was forced to resort to a blend of historical detective work, inspired guesses and ingenious invention. Here was learning reborn, yet at the same time adapted. The result was a superb work of art, one of the masterpieces of the early Renaissance. It was also a supreme achievement of engineering: in all, the dome required four million bricks, weighing around 1,500 tons, and besides inventing a crane to lift them, Brunelleschi later conceived of a novel hoist that proved even more efficient. Once again art had required science; at the very outset of the Renaissance these two were inseparable, advances in one proving impossible without advances in the other.

The building of the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore would take Brunelleschi more than fifteen years, at last being completed in 1436. This spectacular new feature would transform the skyline of Florence; yet at the same time the city was also being transformed at street level. Whilst Brunelleschi worked on the dome, he continued working for Cosimo on the Medici Chapel in the church of San Lorenzo, and completed many other projects in the city. Now that his father Giovanni was dead, Cosimo de’ Medici felt free to begin pouring money into a number of building schemes, and in the midst of medieval Florence a new Renaissance city was beginning to appear. The architects chosen by Cosimo – such as Brunelleschi, Donatello and Michelozzo – had all studied the ruins of Ancient Rome, and now proceeded to construct their own versions of its classical style in Florence.

Fig 5 Brunelleschi’s dome, Santa Maria del Fiore

The new art may have required science, but it also required money, and this was largely provided by Cosimo, who according to one admiring historian ‘appeared determined to transform medieval Florence into an entirely new Renaissance city’. This was hardly an exaggeration, for Cosimo funded the construction, or renovation, of buildings ranging from palaces to libraries, churches to monasteries. When his grandson Lorenzo the Magnificent examined the books many years later he was flabbergasted at the amounts that Cosimo had sunk into these schemes; the accounts would reveal that between 1434 and 1471 a staggering 663,755 gold florins had been spent. (Cosimo died in 1464, but the legacies and unfinished projects went on.) Such a sum is difficult to put into context; suffice to say that just over a century beforehand the entire assets of the great Peruzzi Bank at its height, accumulated in branches all over western Europe and ranging beyond to Cyprus and Beirut, were the equivalent of 103,000 gold florins.

Yet such munificence was always built on a foundation of solid banking practice. An examination of the Medici Bank records shows that while it made use of the most efficient financial instruments available, it was in no way innovative in its practices; it was if anything highly conservative compared with other similar institutions. Neither Giovanni di Bicci nor Cosimo de’ Medici introduced any novel methods or ways of doing business, their practice being based entirely on the efficient and prudent use of proven methods pioneered by others. This should always be borne in mind, for it was only this, and the Medici political organisation, that made all Cosimo’s other activities possible. No matter what he was doing, he was always first and foremost, every day, a cautious and highly astute banker. Indeed, the only persistently creative element in his accounts appears to have been with regard to his tax returns; but then this too had long been an established Italian banking tradition.

Cosimo may have been conservative in his banking practice, and may have consciously conducted himself in a modest and retiring fashion, yet surprisingly he was capable of tolerating the most extravagant behaviour amongst his protégés. This is perhaps epitomised by an incident involving the touchy Donatello, who was probably his favourite. One day, on the recommendation of Cosimo, a Genoese merchant commissioned Donatello to produce a life-sized bronze head; but when Donatello had finished, the merchant refused to pay for it, claiming that Donatello was charging him too much. Cosimo was called in to mediate, and ordered the head to be carried to the roof of his palazzo, where it was placed on the parapet, so that it could be seen in the best light. Yet still the Genoese merchant complained that he was being asked to pay too much, pointing out that Donatello had only taken a month to complete the commission and was charging more than fifteen florins. Upon hearing these words Donatello became incensed, declaring that he was an artist, not a labourer who was paid by the hour. Before anyone could restrain him, Donatello leaped forward and pushed the bronze head over the parapet, whereupon it crashed down into the street below, shattering into fragments. The merchant was immediately smitten with remorse at what he had caused to happen, and promised to pay double if Donatello would make him another head; but despite the merchant’s promises and Cosimo’s pleadings, Donatello remained adamant, refusing point blank to produce anything for the merchant, even though he was a friend of Cosimo.

Surprisingly, Cosimo did not censure such behaviour. He appears to have been one of the first patrons to recognise the new kind of artist being produced by the Renaissance, insisting: ‘One must treat these people of extraordinary genius as if they were celestial spirits, not as if they are beasts of burden.’ The effect of humanism had been to encourage a new emphasis on individuality; the personality was becoming recognised as an integral part of what a human being was – not just the prerogative of rulers. Donatello was very much a case in point; his complex personality consisted of conflicting elements, which would inform his art in a manner hitherto unseen. Yet paradoxically, his character retained a distinctly medieval otherworldliness, and he cared so little about his personal appearance that in the end Cosimo decided it was time he smartened up. To encourage Donatello out of his scruffy ways, Cosimo gave him a set of fine red clothes, complete with a new cloak; Donatello wore his smart red outfit for a few days, but soon reverted to his habitual working-mans clothes, and Cosimo gave up.

Despite Donatello’s prickly pride, he in fact cared little for money; he would place what he earned in a basket in his studio, telling his assistants that they could help themselves without asking, whenever they needed some ready cash. Yet for such trust, he demanded absolute loyalty. When one of his assistants ran away, Donatello is said to have chased him as far as Ferrara with the intention of murdering him. Though there is probably more to this story than meets the eye: Donatello was homosexual, and many of his violent outbursts certainly resulted from passionate entanglements. His first appearance in the records is as a fifteen-year-old involved in a fight with a German, and according to this report Donatello’s opponent ended up being hit over the head with a heavy piece of wood, causing profuse bleeding. It was a year later that Donatello set off for Rome with Brunelleschi, and this would mark the beginning of a lifelong friendship, interspersed with stormy interludes – Donatello would receive more than his fair share of insulting poems, but he evidently soon forgot them.

Donatello made no secret of his homosexuality, and his behaviour was tolerated by his friends; certainly Cosimo is known to have played his part in patching up at least one lovers’ quarrel between Donatello and one of his young assistants. Attitudes to homosexuality in Florence appear to have been ambiguous. The passionate young Italian male found himself in a difficult situation, with girls marrying much younger than men and a high premium being placed on their virginity. As a result, any young blood who attempted to interfere with this was liable to find himself in serious trouble, not to say mortal danger, from the offended family; deflowering a virgin meant devaluing a considerable family asset, to say nothing of dishonouring the family and any prospective groom.

All this meant that sodomy amongst young men was covertly tolerated, despite the frequency of edicts expressly forbidding this practice (1415, 1418, 1432). In fact, homosexuality was seldom prosecuted, and its practice was so rife in Florence in the fourteenth century that the German slang term for a ‘bugger’ was Florenzer. When Florence lost a war against Lucca in 1432, the more diehard members of the Florentine military blamed their defeat on the fact that so many of the conscripts were homosexuals. The authorities were deeply worried by this and decided that something had to be done about it; yet another decree was issued banning all kinds of homosexual behaviour, but this time they also decided to take more positive action. A number of licensed bordellos were opened around the Mercato Vecchio (Old Market), and the prostitutes who worked from them were known as meretrici – meaning ‘to merit paying’, the source of our word ‘meretricious’. As was the custom elsewhere in Italy, all meretrici were required to wear distinctive gloves, high-heeled shoes and little tinkling bells in their hair; they were also instructed ‘to keep out of respectable churches’. The introduction of meretrici was to prove highly popular in Florence, and would remain so for years to come – within 130 years prostitutes numbered one in every 300 of the population.

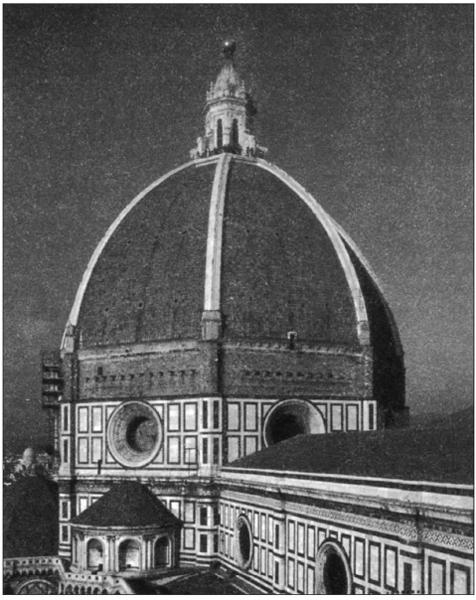

Fig 6 David with Goliath’s Head by Donatello

However, none of this was to influence Donatello, whose masterpiece would prove to be one of the most overtly homosexual artworks of its era. This was the bronze life-sized David that he produced for Cosimo, which was placed on a pillar in the inner courtyard of the Palazzo Medici and would become one of the most treasured of all the works commissioned by the Medici. Despite this fact, it has been argued that this was not originally created for the Medici, yet merely bought by them, as there is no record of it being commissioned; but the evidence against this view is to be found in the laurel wreath that adorns the hat on David’s head and the larger laurel wreath that encircles the base of the statue. The saint to whom the Medici church was dedicated, and the patron saint of the Medici family, was San Lorenzo; this is echoed in the Italian for laurel, which is lauro.

This statue is an unabashed masterpiece of homoerotic sexuality; and its sensuous nudity is only emphasised by the young David’s calf-length ornamented leather boots, large floppy ‘country-style’ hat and the long curly tresses that fall down over his shoulders. His open-toed boot rests casually on the helmeted severed head of the slain giant Goliath, but in such a way that the exaggerated feathered wing of Goliath’s helmet softly caresses his inner thigh. The specially darkened bronze adds highlights to the soft smoothness of the flesh, giving it a sensuality that ensures this is no idealised Renaissance figure, or emblematic ancient hero, at which we gaze in awe; on the contrary, this is a figure that beguiles the eye, all but enticing the spectator to feel its radiant surface. Yet such is the power of its beauty that somehow it transcends its flagrant homoeroticism: this is much more than an object of desire, it is an aesthetic masterpiece.

Once again, there was a major scientific aspect to this work of art. It was the first free-standing bronze sculpture to be produced in over a millennium, and as such represented the rediscovery of a lost knowledge; its casting alone was a huge technical achievement. Previously statues had been created for niches in buildings, or as architectural embellishments, rather than as complete objects in themselves; and the fact that this sculpture is to be seen in the round also required further scientific understanding. Donatello’s David is a work of great anatomical precision, requiring more than a passing knowledge of this subject. The adolescent podginess softening the line of the rib bones, the slightly protuberant stomach, the swivel of the hips and the lined skin on the forefinger clutching the sword all indicate an eye for physiological detail. Yet at the same time there is no denying that this is a statue of a particular human body, a particular individual. The sensuality of its hand-on-hip pose may appear to outrage sexual orthodoxy even now, but it is not an exaggeration; anatomically and psychologically it is masterful – art and science combined here too.

Yet despite all this, Donatello’s David remains something of a mystery. David was emblematic for the Republic of Florence: the hero who slew the Goliath of oppression was also seen as the embodiment of a republic free from autocratic rule. This would explain why it was originally commissioned, just as Donatello’s homosexuality may explain why the commission was fulfilled in this particular way. Yet was Donatello really expected to produce such a statue? There would certainly have been preliminary sketches and models – which would have been seen by Cosimo, so he must have known what was coming; and why did the finished work prove so acceptable that it was given the place of honour in the middle of the courtyard of the Palazzo Medici? There is no record of it having caused any controversy when it was first erected; indeed, the very opposite was the case – the Medici family, and Cosimo in particular, appear to have taken it to heart, despite the fact that this was not a slightly inappropriate statue embodying republican Florence, it was wholly inappropriate.

Yet the key to this statue’s mystery may well lie in its very inappropriateness; its supreme beauty, which transcends any particular sexuality to an almost hermaphroditic degree, may well contain esoteric meaning. The hermaphrodite was a compelling figure in classical mythology – a combination of Hermes and Aphrodite – who also played a central role in alchemy and hermeticism, both of which underwent a revival during the Renaissance, along with other such esoteric ‘sciences’ as astrology, magic and geomancy. These had all thrived in Constantinople, and arrived in western Europe with the influx of manuscripts and adepts that preceded the fall of the Byzantine Empire, with the result that the Renaissance saw a rebirth of rational and irrational knowledge. (Indicative of this ambivalence is the fact that before Ficino could finish his translations of Plato, he would be diverted to translate the Corpus Hermeticum by the legendary Greek alchemist Trismegistos.) It could well be that Donatello’s David was intended to represent some kind of summation of knowledge, or of completed beauty, whose allusions now escape us; its combination of male and female sexuality would not be out of place in a Platonic ideal of human perfection.