Chapter Two

The Avant-Garde as Network

Let us look at the interconnected literary and artistic vanguard groups of early twentieth-century Barcelona and Madrid concurrently. In doing so, we will instantly see a complicated web of connections linking these two cosmopolitan centers. We also will see how experimental literature and the arts were instrumental in reformulating both Barcelona and Madrid’s cultural identities in a dynamic, complex, and highly interconnected process. While there may not have been a high level of information exchange between these two centers on a daily basis in the way we might see today, there were real, legitimate, and significant connections between individuals and groups linking these two cities. One case that illustrates this point can be found in the life and work of Ernesto Giménez Caballero, one of the leaders of the avant-garde network in Madrid.

Just weeks after the remarkable success of the Catalan Book Fair in Madrid, Ernesto Giménez Caballero, one of the main organizers of this extraordinary event, which will be discussed in more detail in the final chapter, made an important trip. He flew to Barcelona on Iberian Airlines to exhibit his “literary posters” in the most cutting-edge art gallery in Spain. Each one of the literary posters depicted a contemporary writer, critic, editor, or artist using mixed media, especially colorful paper and newspaper cutouts. After allegedly being hassled by military police at the Barcelona airport, he convinced the authorities that he was simply returning a cultural visit. The Catalans had just exhibited their books in Madrid, and now he was exhibiting his artwork in Barcelona. He was allowed to display his literary posters at the Dalmau Galleries from January 8 to 20, 1928, but only under the supervision of police officers. On the opening day of the exhibit, Gustavo Gili, a successful Catalan book editor, purchased all of Giménez Caballero’s posters for an undisclosed amount. But before Giménez Caballero handed them over to Gustavo Gili, he exhibited the posters in Madrid at an art gallery located in an exhibiting space of the Ediciones Inchausti publishing company.

The contemporary poet Pedro Salinas attended this second showing of Giménez Caballero’s innovative approach to literary criticism through visual art. In an article published by Giménez Caballero in Madrid, he describes a dialogue he had with Salinas.1 According to this account, Salinas remarked that the collection would be more complete if it included a poster that reflected on Spain’s new literary movement as a whole, not just some of its protagonists. Giménez Caballero responded to Salinas’s challenge at the closing ceremony of the Madrid exhibit. In his response, the creator of these literary posters argued that the center of Spain’s experimental literary activity and cultural production was not Barcelona, as highly suggested by the Catalans during their recent Book Fair in Madrid, but Madrid.

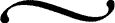

To argue his point, he drew the “Theorem of New Spanish Literature” on a blackboard. This image would later be published in his periodical La Gaceta Literaria, accompanied by a fragment of his talk.2 He depicted the Iberian Peninsula as a pentagon that contained various networks in the form of five small triangles from which the “new Spanish literature” was emerging. According to his visual, verbal, and written explanation, none of the three main triangles inside the pentagon are connected. In other words, there are no points of connection between the various groups creating new literature on the peninsula. In fact, he uses this image, the public occasion as well as the follow-up published article, to prove that Madrid is the center of Spain’s new literary phenomenon. While Giménez Caballero was relatively safe making this argument from his hometown of Madrid, he chose not to make the same argument at the Dalmau Galleries in Barcelona several months earlier. Or at least there are no indications that he did so, at least not publicly.

Figure 2.1. Theorem of New Spanish Literature by Ernesto Giménez Caballero.

Giménez Caballero begins to prove his “theorem” by asserting that the shape of Spain is that of a pentagon. Inside this figure, he drew five triangles. The first triangle is located to the north and covers the region of Catalonia. Outside of the pentagon, there is an arrow to the right above the geometric shape representing Catalonia, to suggest that this region functioned like a funnel for all of the ideas pouring in from the rest of Europe. In order to measure the size and shape of each of the triangles, he uses the literary and cultural periodicals, which he considers to be “el núcleo absoluto donde se insertan numeradores y denominadores” (the absolute nucleus where numerators and denominators can be found). He uses the periodicals to mark the figure’s coordinates.3 The coordinates, then, are indicated on the map using the initial of the city from where the periodical originates. Therefore, the “G” is an abbreviation for Granada, the city where Gallo is published.4

Once he determines the coordinates for each of the triangles, he labels each of them: Alpha (a) = Catalonia and Valencia; Beta (b) = Castile and Murcia; Gamma (g) = Andalusia; (d) Delta = Galicia and Portugal.5 Before defining their value, he compares them in the following manner: First, “a < b > g > d” (alpha is less than beta, which is greater than gamma, which is greater than delta; or Catalonia/Valencia is less than Castile/Murcia, which is greater than Andalusia, which is greater than Galicia/Portugal). Second, “b > a > g > d” (Castile is greater than Catalonia, which is greater than Andalusia, which is greater than Galicia and Portugal). Third, “g < a < b < d” (Andalusia is less than Catalonia, which is less than Castile, which is smaller than Galicia).

In conclusion, he determines that the new literary movement in Madrid is greater than that in Barcelona, which is greater than that in Andalusia, which is greater than that of Galicia and Portugal. Yet he does not offer any proof or explanation as to how he came up with any of these calculations. His evaluation is completely subjective, even though he would like to seem objective by using the guise of geometry.

The triangle that corresponds to the new literary movement in Catalonia and Valencia is nearly “all political,” he states in the already referenced article, and not so literary. Not only did he disapprove of the fact that both the Nova Revista and L’Amic de les Arts published entirely in the “vernacular,” that is, in the Catalan language, but he loathed it. As we will see in the final chapter of this book, Giménez Caballero distrusted periodicals that centered themselves exclusively on Catalan issues. He strongly believed that the new literary movement had to be inclusive of the peninsula’s plurality of cultures and languages and that the different regions of Spain had to collaborate. There was no room for separatisms in his vision of Spain’s new literary movement. In his theorem he explains that the triangular area that corresponds to Madrid can be characterized as having everything that the one that corresponds to Barcelona does not, especially its “desdén por la política” (dislike of politics). Giménez Caballero goes on to say that if Madrid’s cultural periodicals included any politics, it was so lyrical that one could argue that it was more literary language than anything else. The only politics of Madrid periodicals such as Revista de Occidente and La Gaceta Literaria was to “correct” Barcelona’s disdain toward Madrid. Giménez Caballero believed this could be achieved not through traditional politics, but through avenues opened up by collaborating in the new literary and artistic movement, organizing events like the Catalan Book Fair in Madrid, and getting them covered in the press of both cities.

Rather than enter into dialogue with the Catalans, Giménez Caballero would often impose his idea of what he thought was correct on them. It is almost as if he truly believed that just because he included Catalan news in the periodical he directed (La Gaceta Literaria), the Barcelona press would reciprocate—as if the historic tensions between the two cities could be solved overnight and without any true dialogue. His mission, through his bimonthly periodical, was to fight for an “indigenous Spain”; that is, a nation composed of many subgroups, including Castilians, Catalans, Portuguese, Sephardic Jews, and Latin Americans.6 For this reason he called for the “trinity of peninsular languages,” the three languages being Spanish, Catalan, and Portuguese, in order to achieve the “Iberian ideal of cooperation founded on geography and culture.”7 No other periodical involved in the new literary movement in Spain worked so diligently toward creating a more unified Spain through the arts. The value he placed on this “higher” mission may be one of the reasons why the beta triangle, the one corresponding to Madrid, is greater than the alpha or the one corresponding to Barcelona. We can only deduce that this is the reason why he considers Madrid to be greater Barcelona, based on the variables he introduces into his equations.

When the editor of La Gaceta Literaria differentiates between Barcelona and Madrid by accusing the people of Barcelona of being more influenced by the ideas that funnel in from France and Italy, in contrast to Madrid’s “autochthonous influences,” he places more value on all that is Spanish than that which is “foreign.”8 In Madrid, new ideas come from writers and intellectuals like José Ortega y Gasset, Miguel Unamuno, Azorín, Pío Baroja, Juan Ramón Jiménez, Eugeni D’Ors, Ramón Gómez de la Serna, Antonio Machado, and Ramón Pérez de Ayala. Without further explanation, Giménez Caballero concludes that ultimately, the new literary movement in Spain is one that is defined by its limits. He was setting himself up to be the hero of uniting a divided Spain through his multilingual periodical. Correspondingly, he considered his periodical and his city to be the center of Spain’s literary and artistic vanguard movement.

Ernesto Giménez Caballero was not the only one who took a centralizing stance in shaping the development of the Avant-Garde phenomenon in Spain. A few years earlier, the Madrid-born poet and literary critic Guillermo de Torre published the first book-length study written in Spanish describing all of the major European literary and artistic avant-garde movements: Literaturas europeas de vanguardia (Literatures of the European Avant-Garde) (1925).9 In this lengthy text, he describes every artistic and literary avant-garde style in Europe, including Madrid’s Ultraísmo movement, but fails to mention Barcelona at all. According to the histories that Ernesto Giménez Caballero and Guillermo de Torre construct, Barcelona played little to no role in the development of Spain’s Avant-Garde as a whole. However, if we place the literary and artistic networks of Barcelona and Madrid on the same playing field, rather than dismissing one or the other, a system of connections linking these two centers is revealed. Seen in this way, the new literary and artistic movement suddenly plays a much larger role in the development of Barcelona and Madrid’s identity politics at the beginning of the twentieth century. More importantly, we can see how the relationships between the people and groups involved in reshaping the identities of these two urban centers at the level of this literary and artistic revolutionary movement, known as the Avant-Garde, were dynamic, complex, and highly interconnected. Giménez Caballero, for one, could not claim that Madrid was the heart of the Avant-Garde movement in Spain without mentioning its relationship to Barcelona. Specifically, he argued that the new literary movement in Spain was greater in Madrid than in Barcelona.

In a more contemporary account of artistic activity in Spain, Jaime Brihuega’s indispensible Las vanguardias artísticas en España: 1909–1936 (The Artistic Avant-Gardes of Spain) (1981) offers an impressive report of invaluable documentation.10 But, the way in which he presents this data implies a disconnection between these two cities, as if it were a given. The art historian compiles a year-by-year account (in some instances a month-by-month, sometimes day-by-day, listing) of the many exhibitions, books, periodicals, meetings, happenings, lectures, individuals, and political acts associated with the origins and development of the Avant-Garde in Spain. This rendering implies that both communities operated within independent and mutually exclusive orbits of cultural production, similar to the way in which Ernesto Giménez Caballero depicted it in his theorem of new literature in Spain. While there may not have been excessive communication between writers and artists from these two cities on a daily basis, it does not mean that there were no links.

The difficulty of recounting the dynamic nature of Spain’s cultural scene during the beginning of the twentieth century is apparent from the start of Brihuega’s account. He begins his narrative with 1909, the year that the first futurist manifesto written by the Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti was translated into Spanish, in a literary periodical edited by Ramón Gómez de la Serna called Prometeo (Madrid, 1904–12). The original Italian manifesto was published in the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro on February 20, 1909:

1909.—Partimos de la publicación del Manifiesto Futurista en ‘Prometeo.’ Ese mismo año, en marzo, Gabriel Alomar había dado la noticia de la aparición de este manifiesto en París, diecisiete días después de su publicación en ‘Le Figaro.’

(1909.—We begin with the Futurist Manifesto in ‘Prometeo.’ This same year, in March, Gabriel Alomar announced the appearance of this manifesto in Paris, seventeen days after it appeared in ‘Le Figaro.’)11

This art historian would like to begin his annotated chronology of the history of the Avant-Garde in Spain with the publication and Spanish translation of the Italian futurist manifesto in Madrid. Yet, in good faith, he cannot do so without making a reference to Barcelona. The Catalan writer Gabriel Alomar, living in Barcelona at the time, had already philosophized about another type of futurism, a Catalan futurism, several years before Marinetti. As Brihuega points out, Alomar reported the news of the Italian futurist manifesto in Barcelona about one month before Ramón Gómez de la Serna did so in Madrid (April 1909).12 In fact, Alomar broke the news of the Italian manifesto in Barcelona (March 9, 1909) before it was even reported in Marinetti’s homeland, Italy (March 11, 1909, in the periodical Poesía V).

After the chronological complications involved in explaining the Marinetti (Paris)–Alomar (Barcelona)–Gómez de la Serna (Madrid) triangle that is necessary to mention when describing the inception of futurism in Spain, Brihuega settles for simplicity. In order to avoid such future entanglements, he opts for a city-based chronology and chooses as his starting point the year 1911. He avoids further confusion by focusing on the avant-garde developments in Spain on a city-by-city basis. In doing so, he establishes Madrid as the central axis of his chronology. Brihuega traces the cultural history of the vanguard movements in Spain by centering his timeline in Madrid, while Barcelona and other cities are treated laterally. He maintains this structure throughout the book, until he reaches the year of the onset of the Spanish Civil War (1936), when his account ends.

Separating these major events in Spain by city oversimplifies the time period, causing the impression that avant-garde activity in each city operated on its own, as if there were no contact or communication connecting them. The other cities in Spain that Brihuega mentions—Barcelona, Bilbao, La Coruña, and Seville—all seem to function independently, like nerve centers feeding off the central medulla of Madrid. This organizational structure gives his readers a sense that all avant-garde artistic activity in Spain originated in Madrid or depended on it, which is certainly not the case. This disconnected account, like so many others, further exaggerates the distance between these cities, leading the reader to believe that there was no dialogue of any kind. Indeed, a significant geographical and cultural distance divided Barcelona and Madrid, but they were not completely unaware of one another, as evident in the daily press and specialized periodicals and other evidence gathered for this study. The artistic and literary visionaries of Barcelona and Madrid, just like many others who participated in the new literary and artistic movement of both cities—politicians, doctors, philosophers, business people, journalists—did not function in complete isolation from one another. In fact, the case is quite the opposite—they oftentimes acted and behaved in relation to one another.

Introduction to Network Studies

The Avant-Garde in Spain is a cultural phenomenon comprised of networks, not isolated groups as presented in Ernesto Giménez Caballero’s theorem explaining the new direction of literature and the arts, as discussed above. Up until now, many have approached the artistic and literary movements that evolved throughout Europe during the first three decades of the twentieth century—cubism, futurism, expressionism, dadaism, and surrealism—as discrete and separate entities, instead of interconnected systems. To isolate them from each other denies their essence. Those who practiced the Avant-Garde in Spain were a diverse group of individuals. Many lived in Barcelona and Madrid, but they resided in others cities as well. One aspect of this diversity was that some of these artists and writers were born in Spain, but others were not. Some of them came from wealthy families, but others had more humble beginnings. Most of them traveled, and many of them contributed to literary and artistic periodicals from a variety of cities in Spain and beyond. Considering the dominant, more conservative cultural scene at the time, believers in and practitioners of the Avant-Garde in Spain were a minority. In order to stay alive, so to speak, they networked with other believers, regardless of nationality, city of origin, age, social status, religious beliefs, or sexual preferences. In studying this cultural phenomenon as a network of networks, a hierarchy of power is revealed. In order to make out these distinctions, different questions must be asked, new evidence collected, and alternative ways to describe and analyze social structures must be adopted.

When we think about social networking today, we think of Internet sites like Facebook and Twitter. Within these digital universes, we can easily discover and quickly connect with friends. We can post pictures and describe exactly what we are doing right now. We can document our lives and share them with anyone who cares to know. Anthropologists and sociologists have been studying and theorizing about patterns of human relationships and how they function since the 1960s. More recent network analysis focuses on how groups and individuals communicate information and knowledge. Analysts study the links among social systems then provide visual renderings of these relationships. The purpose of these maps is to probe the underlying deep structures connecting and dividing social systems.

Those who study social networks generate hypotheses, collect data, analyze results, and propose theories about how humans communicate. It has been critical to explore the area of network studies in order to articulate and understand how the social networks between the people and groups of avant-garde Barcelona and Madrid behaved. Just like the subjects of structural network analysis, actors of the Avant-Garde in Spain were also enmeshed in complex social networks cutting across national, geographical, and linguistic boundaries. The methodology used in this analysis focuses on links between nodes in both cities in order to better define the nature and function of the cultural movement in Spain as a whole. As pointed out by network analysts, the basic strength of the total network approach is that it permits simultaneous views of the social system as a whole by analyzing the parts that make up the system.

In general, a network requires two key elements: relational ties and nodes. Both of these foundational elements surfaced in my search for relationships that connected people, groups, events, organizations, literary reviews, and art journals from Barcelona and Madrid. For instance, there were people and periodicals that functioned as centers of information and its dissemination. Then there were links that connected these various centers. Consequently, the conceptualization of the cultural moment in question here is as a system of networks. Analyzing the individual parts of the Avant-Garde movement allows for simultaneous views of the system as a whole. It also permits the connections and disconnections between the individual parts to emerge from the data. It was not one or five individuals responsible for the communication that occurred between these two cities, as has been suggested in the past, but many more; however, there were some that were more influential or powerful than others. If one individual played a key role in communicating news with people from the other city, let us say in the direction of Madrid to Barcelona, it was likely that this person in Madrid knew at least four other people in Madrid who together may have known at least ten people in Barcelona. In this way, as relationships between individuals that comprised these systems of contacts were identified, the web of connections became increasingly complicated. At the same time, it revealed deeper structures of behavior between the people of Barcelona and Madrid that ran parallel to Spain’s political struggles at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Network analysis, in the strictest sense of the discipline, is much more analytical than what I intend to do here. Traditional network analysts compile data on the number of times one individual, for instance, wrote letters to another. Then they enter this data into a computer program to create a graph or map. The purpose of creating these maps is so that researchers can represent and explore the nature and properties of certain relations. While I do not plan on entering my data into a network analysis software program at this time, I have borrowed some of the key concepts of the discipline to approach the kinds of relationships that surfaced in my research. A node, for example, can be a person, group, or organization, and it is one of the fundamental concepts of networks. In this study, nodes are leaders of the Avant-Garde in Madrid and Barcelona, or influential periodicals, important art exhibits, or major cultural events.

According to network analysis, once the nodes have been determined, links that connect them are identified and described. Nodes can be linked directly or indirectly. A direct link occurs when two nodes connect without the assistance of a third node. Indirect links occur with the assistance of another node. Networks can be sparsely or highly connected. If the system is very insular, it is sparsely connected. But if the network is open to communication, it is described as being a highly connected system. Networks also can be centralized or decentralized. The centrality of the network depends on whether the people that compose the network are vital in relation to the others in the group. The extent to which an actor is central to a network depends on factors such as the number of direct links with other actors or the actor’s proximity to, or ability to easily reach, all the other actors in network. Within network analysis we must ask ourselves questions such as: Is it just one individual running the network, or is it multiple people? How is this individual connected to the other actors in his or her network? And how do these relationships affect the overall behavior of the network?

The way the avant-garde movements in Spain worked was that one individual would be the editor of a literary review that disseminated these new ideas and practices, but usually that was not all he did.13 Oftentimes this individual was also a poet, journalist, artist, writer, politician, teacher, or student. Also, it was rare for this person to work in isolation. The periodical this person directed did not exist in a vacuum, nor did he or his staff. The literary periodical competed and co-existed with several other journals within the same city and neighboring towns. Most scholars have treated the avant-garde system in Spain as if it were decentralized. Yet, one of the main objectives of periodicals devoted to the new literary and artistic movement in Barcelona and Madrid was to connect with other avant-garde enthusiasts outside of their own city. If we were to create a new version of Ernesto Giménez Caballero’s map of new literature in Spain, it would consist of several centers, all connected to one another, similar to what a telephone map from the late 1920s (fig. 2.2) looked like.

Figure 2.2. Map of Spain’s Telephone Network.

Desire for interconnectedness is clearly evident in the fact that most of the cultural periodicals from this period included a section dedicated explicitly to reviews of journals, books, art shows, and performances in the city they represented and, in some cases, in others as well. Being informed of what was happening in other avant-garde circles was of primal importance to the survival and strength of the movement as a whole. If it were not so important to connect with other believers or competitors, most of the editors would not have bothered wasting time, space, or money on such a section in their journals. In some instances, these sections would initially be situated at the end of the journal, but were later transposed to the front of the periodical. The placement of these reviews in the journal demonstrates readers’ interest in knowing about the world outside of their little magazine. This desire to be informed of the quick developments and introduction of new avant-garde styles demonstrates that overall, the movement, as a system or network, desired to be more connected than disconnected.

The links that connect the nodes are central to studying networks because they define the nature of the communication between them. Relational ties have numerous properties, such as strength, symmetry, and multiplicity. Within formal network analysis, lines on a graph or chart traditionally represent the relations between nodes. These lines are known as links, ties, or arcs. Relations can be directional or nondirectional; binary or valued; uniplex or multiplex; tangible or symbolic. All of these major network concepts developed by Daniel Brass in 1995 are useful for understanding the complex relationships between the artistic and literary networks of Barcelona and Madrid during their avant-garde moment at the beginning of the twentieth century.14

Following the lead of network analyst Barry Wellman, first I would like to describe how social networks are measured at the most basic level.15 The first of seven main concepts is direction. For instance, an indirect link that connects two nodes consists of two people, or actors, linked to one another through a third. The connectivity of a network is the extent to which actors in networks are linked to one another, either by direct or indirect ties. As applied to a specific case in Spain’s Avant-Garde, Federico García Lorca was a poet from the south of Spain who moved to Madrid as a young man to study. A second actor, the Uruguayan painter Rafael Barradas, met Lorca in Madrid in 1919 at the place where Lorca was living, the Residencia de Estudiantes (Students’ Residence). Barradas introduced Lorca to a third actor, the Catalan art critic Sebastià Gasch. Barradas first lived in Barcelona, moved to Madrid, and then returned to Barcelona. When Barradas moved to Barcelona for the second time, he sent a telegram to his friend Gasch inviting him to meet Lorca, who was visiting Barcelona. Gasch and Lorca were the same age and like minded. Barradas was almost ten years older than both and saw the opportunity for a friendship between these two people whom he admired and who were both involved in the new literary and artistic movement, but residing in different cities. Using network analysis terminology, then, Lorca and Gasch were linked indirectly by Barradas. This relational tie can also be described in the opposite direction: Gasch was indirectly linked to Lorca through Barradas. All three actors, Barradas, Lorca, and Gasch, can be considered as nodes of the same overall network (the Avant-Garde in Spain), which was made up of at least two other avant-garde networks: (1) the one in Barcelona that included Barradas and Gasch, and (2) the Madrid system that also included Barradas and Lorca. In time, Lorca became a member of the Barcelona network and Gasch of Madrid’s, precisely because of this original connection and the friendship that developed as a result.

Since Sebastià Gasch is the lesser known of the Barradas–Lorca–Gasch cluster discussed here, a few biographical notes are in order. Sebastià Gasch (Barcelona, 1897–1980) was one of the most astute modern art critics of his era. Early on in his career, he wanted to be a painter. He associated himself with one of several modern art schools in Barcelona, called El Cercle de Sant Lluc (Saint Lluc’s Artistic Circle), which officially hired him as their librarian in 1923. It was through his connections here that he met the Catalan avant-garde painter Joan Miró (Barcelona, 1893–1983), about whom he wrote his first published article as an art critic in the Barcelona press (Gaseta de les Arts, December 1925). Over the course of the following year, Gasch went on to write with great objectivity about the works of similarly innovative artists and poets, such as Salvador Dalí, Rafael Barradas, and Federico García Lorca. Even though Gasch was a firm believer in cubism, new architecture, and new film, he also is known to have once said: “¡Vanguardismo! La palabra odiosa no ha producido únicamente paradojas” (Vanguardism! That hateful word has produced nothing but paradoxes).16

Gasch is unique in that he published most of his journalistic essays in one of two journals: L’Amic de les Arts, centered in a beach town located just outside of Barcelona called Sitges, and La Gaceta Literaria, which was located in the center of Madrid. In this second publication he edited his own section titled “Gaceta de arte” (Art Gazette) (1929). We can also find his byline in other cultural periodicals from Barcelona (D’Ací d’allà, Les Arts Catalanes, Butlletí, Fulls Grocs, Gaseta de les arts, Hélix, Mirador, La Nova Revista, L’Opinio, Quaderns de Poesia); as well as newspapers (La Veu de Catalunya, La Publicictat). He also published in periodicals based in other places in Spain (Gallo, Mediodía, Papel de Aleluyas, Verso y prosa) and outside of Spain (1928 [Havana]; A.C., Atlántico, Amauta, Circunvalación [Mexico]; OC, Democracia [Rosario, Argentina]). In 1928, he signed the infamous anti-artistic manifesto, Manifest Groc (Yellow Manifesto) along with Salvador Dalí and Lluís Montanyà.17

In an interview with a journalist from the Catalan newspaper La Nau (March 17, 1928), Dalí gives Gasch credit for having the original idea for the Manifest Groc after long hours of conversations with him in Barcelona.18 Nevertheless, it would be Dalí who would write the first version of said document in February 1928.19 Despite his devotion to anti-art, Gasch vehemently renounced surrealism. By 1932 his beliefs diverged so much from those of his friend Dalí that the two parted ways indefinitely. From this brief description, we can already see that Salvador Dalí was another node involved in the Barradas–Lorca–Gasch cluster connecting the avant-garde networks of Barcelona and Madrid, but his involvement will be discussed in more detail later.

After direction, frequency is the second element to consider in studying networks. Frequency measures how many times or how often a link occurs. After Barradas introduced Gasch and Lorca, the two avant-garde enthusiasts exchanged letters frequently over the next few years. The frequency of a link determines its strength. Again, as explained by Barry Wellman, the strength of a relationship consists of the amount of time, emotional intensity, intimacy, or reciprocal services between two actors. In Lorca’s letters to Gasch, we can see the strength and frequency of their link by the intimacy he expressed in these letters. Notice the increasing level of emotional intensity of Lorca when directing himself to Gasch over time: “Querido Sebastián Gasch; Querido Gasch; Querido amigo Gasch; Mi querido Gasch; Querido Sebastián; ¡Mi querido Sebastiá!; ¡Querido Gasch!; ¡Querido!; Queridísimo Gasch; Mi queridísimo Sebastián” (Dear Sebastian Gasch; Dear Gasch; Dear friend Gasch; My dear Gasch; Dear Sebastian; My dear Sebastian! Dear Gasch! Dear! My very dear Gasch; My very dear Sebastian!).20 At the beginning of the relationship, Lorca addressed himself to Gasch formally, using both his first and last name. As the relationship developed, he used either his first or last name. The “dear” became “dearest,” and exclamation marks are introduced. The frequency, intimacy, and intensity of these exchanges indicate a strong link between these two actors of this one particular cluster.

Another measure of frequency is stability, or the existence of the link over time. In the case of Lorca and Gasch, after they met in 1927 they were friends until Lorca’s assassination in 1936. If their correspondence is a measurement of the stability and frequency of this link, the period of greatest intensity in their relationship occurred between 1927 and 1928, during Lorca’s inception to the Catalan avant-garde network and during Gasch’s initial involvement with that of Madrid. Based on the collection of letters between Lorca and Gasch, it appears that Lorca spent more time writing to Gasch than the other way around. One reason for this imbalance could be that when Lorca and Gasch first met in Barcelona, Lorca was just starting a literary periodical in his hometown in the south of Spain. The mission of this literary review was to be “anti-local” and “anti-provincial.” It was to be a magazine from Granada but intended for an audience well beyond Granada. In other words, Lorca expected that his local network in the south of Spain would reach Madrid and Barcelona.

Lorca needed help getting this ambitious project off the ground. He also needed people who would be willing to work for free and who were connected to the right circles in Barcelona and Madrid. At the same time, Lorca also wanted his review to be of the highest caliber. Lorca knew that Gasch was a well-respected art critic, and as we can read in his letters, he highly valued Gasch’s work. Lorca also preferred to fill his magazine with articles written by friends, not strangers. In the end, Lorca and his brother Francisco only published two issues of his little magazine, called Gallo (February 1928, April 1928). Interestingly, the last issue includes a Spanish translation of the “anti-artistic” Catalan manifesto signed by Salvador Dalí, Sebastià Gasch, and Lluís Montanyà. Lorca has been credited with the translation, but it is possible that he had a little help from his Catalan friends, either Salvador Dalí or Sebastià Gasch.

Lorca seemed to have intended Gallo to function as a way to inform others about the relationships he had recently established with Barcelona and Catalonia. The Catalan painter Salvador Dalí drew the icon of the rooster, the Catalan art critic Lluís Montanyá wrote an article about new Catalan literature, and the Catalan art critic Sebastià Gasch wrote about Picasso.21 If Madrid and Barcelona seemed distant, the geographical divide between Granada and Barcelona was even greater. With this experimental magazine, Lorca minimized the gap between the north and the south while simultaneously strengthening his network with the Catalans. Evidently, Lorca intended to bridge the gap between the cultures of Andalusia and Catalonia. As he mentioned to Gasch in one of his letters, Lorca believed that these two regions were the sources of Spain’s vanguard movement. Lorca planned to devote an entire issue of Gallo to Dalí, and if there was enough money, another issue to avant-garde painting from Catalonia and Andalusia. Lorca knew that what he was doing with his journal was revolutionary, and that most would not understand. Lorca expected his reading public to be enraged by his proposition of approximating the two cultures, “aunque haya gente que rabie, patalee y nos quiera comer” (even though people will be livid, kicking and screaming and wanting to eat us alive).22 The avant-garde circles of Andalusia and Catalonia were united by these individual friendships, but also because of the strides these friends took to create the two periodicals preoccupied with the avant-garde spirit, Gallo and L’Amic de les Arts.

The network between Lorca and Gasch is one of multiplexity, because as time passed they became linked by more than one relationship (i.e., Lorca is friends with Dalí, who is also friends with Gasch). In other words, even though Barradas introduced Lorca and Gasch, once they became friends they realized that they were also connected through other friends and colleagues; their networks started to merge based on previous links and common interests, thus creating a larger system beyond their local base. At the beginning of the Lorca and Gasch friendship, they sought each other out for advice and worked together. Lorca introduced Gasch to his friends in Granada by telling them about him and publishing his work in his literary journal from Granada. He also spoke about Gasch in Madrid. At the same time, Gasch wrote about Lorca’s drawings that he liked so much within the pages of the Barcelona cultural magazines. So while Lorca was promoting Gasch in Madrid and Granada, Gasch was promoting Lorca in Barcelona and beyond. As a result, the relationship between these two nodes—Lorca and Gasch—created a whole series of other nodes, links, and clusters.

The final measure used to study social networks is symmetry or reciprocity, which values the extent to which the relationship is bidirectional or mutual. In the case of Lorca and Gasch, their relationship at the beginning was symmetrical and mutual. Lorca would ask Gasch for advice and vice versa; or Lorca would encourage Gasch and vice versa. As their friendship grew, Lorca encouraged Gasch to keep writing in Spanish despite his insecurities with the language, while Gasch supported Lorca in developing his drawing skills, even though he felt more confident as a musician and writer. One of the ways Gasch encouraged Lorca was by reviewing his drawings in the most active avant-garde journals in Barcelona (L’Amic de les Arts) and Madrid (La Gaceta Literaria). At the same time, Lorca encouraged Gasch to continue writing for the journals in Madrid. Lorca felt that Gasch’s knowledge and understanding of the Avant-Garde was much more necessary in Madrid than in Barcelona. In January 1928, Lorca explains:

Yo siempre digo que tú eres el único crítico y la única persona sagaz que he conocido y que no hay en Madrid un joven de tu categoría y de tu conciencia artística, ni tampoco, es natural, de tu sensibilidad. Por eso no debes tener ningún reparo con tus artículos (siempre preciosos y utilísimos) en la Gaceta Literaria. Tú haces mucha falta y debías publicar todavía mucho más. En cuanto a tu castellano, te aseguro que es noble y correcto y llena el fin para que lo utilizas. Pero mucho más importante que el idioma que usas son tus ideas . . . Y en Madrid, querido Sebastián, haces mucha más falta que en Barcelona, porque Madrid pictóricamente es la sede de todo lo podrido y abominable, aunque ahora literariamente sea muy bueno y muy tenido ya en cuenta en Europa, como sabes bien.

(I always say that you are the only critic and the only astute person that I know and that there is no young person in Madrid of your quality and of your artistic conscience, nor, it’s clear, of your sensibility. This is why you should have no qualms with your articles [always lovely and very useful] in the Gaceta Literaria. You are very needed and you should publish even more. In regards to your Spanish, I assure you that it is noble and correct and the means justifies the end. But much more important than the language are your ideas . . . And in Madrid, dear Sebastian, you are much more needed than in Barcelona, because Madrid pictorially is the seat of everything that is rotten and abominable, although now literarily very good and considered throughout Europe, as you very well know.)23

Lorca and Gasch were the kind of friends who encouraged one another regarding their respective goals and pushed one another to overcome their fears. The fact that Gasch would take Lorca’s advice and vice versa shows that they respected one another as professionals, but also as believers in the Avant-Garde. In another letter from Lorca to Gasch, he admits, “If it wasn’t for you, the Catalans, I would have never kept drawing.”24 Lorca and Gasch were also the kind of friends who thanked one another. The strength and quality of the relationships between Lorca and his Catalan friends in Catalonia, such as the one with Gasch, encouraged him to overcome fears and cross major boundaries in his professional and personal life. Lorca respected and admired his Catalan friends and their feelings were mutual. He learned from them and in turn he spoke to his friends in Madrid and Granada about them, thus expanding his network and theirs.

Beyond the basic social network measures mentioned above, actors can play a series of roles including star, liaison, bridge, gatekeeper, and isolate. To summarize, a star is an actor who is highly central to the network (e.g., Lorca is central to the Madrid network, Gasch to the Barcelona network, Picasso and Miró to the Paris network). A liaison is an actor who links two or more groups that would otherwise not be linked, but is not a member of either group. A bridge is a member of two or more groups (e.g., Barradas is a member of both the Madrid and Barcelona networks), while a gatekeeper is an actor who mediates or controls the flow between one part of the network and another (e.g., Giménez Caballero). Finally, an isolate is an actor without links, or relatively few links to others. There are very few cases of isolate roles in Spain’s overall Avant-Garde.

Other kinds of communication linkages between nodes within a social network include migratory and embedded knowledge.25 The first consists of information in easily moveable forms that encapsulate the knowledge that went into its creation (books, designs, machines, blueprints, and individual minds). Following the example stated above, the drawing that Lorca dedicated to Gasch, Leyenda de Jerez (Legend of Jerez), in 1927 is an example of a text that functions as migratory knowledge, because it was shown in an exhibit in Barcelona and it was published in a journal. Another example could be a prose poem that Lorca wrote and dedicated to Gasch, “Santa Lucía y San Lázaro,” which was the only literary text Lorca wrote from January to August of 1927. On the other hand, embedded knowledge is more difficult to transfer; as defined by the network analyst scholar Joseph Badarraco, it “resides primarily in specialized relationships among individuals and groups and in the particular norms, attitudes, information flows, and ways of making decisions that shape their dealings with each other.”26 An example of embedded knowledge could be conversations that occurred between various actors of the Avant-Garde that would be shared with others but of which there is no evidence.

It is clear from Lorca’s letters to Gasch that their relationship functioned as a way of uniting the distant worlds of Barcelona and Madrid, as well as those of Catalonia and Andalusia. Lorca wrote to Gasch: “Como ves, cada día Andalucía y Cataluña se unen más gracias a nosotros. Esto es muy importante y no se dan cuenta, pero más tarde se darán.” (As you can see, each day Andalusia and Catalonia are less distant thanks to us. This is very important and most do not realize it, but in time, they will.)27 As Lorca points out, the cultural unity achieved by this friendship was neither recognized nor understood by their peers in Granada, Barcelona, or Madrid. Yet, for him, it was a critical element of their friendship. Through their common faith in the Avant-Garde, they were uniting their different cultures. In an article he published in L’Amic de les Arts, a Catalan journal out of Sitges, just outside of Barcelona, Gasch laments the small-mindedness of the “Little Catalaners,” or Catalans, who are clueless about what is happening on the other side of the Ebro River; in other words, the land that is south of Catalonia.28 Their friendship, united by a common vision defined by new ideas developing in the literature and the arts, tackled problems, found solutions, and created a unity that most could not achieve, especially not politicians.

Lorca was so spiritually united with his Catalan compatriots of the Avant-Garde that he once declared himself a fervent Catalanist. His links with Catalonia were strengthened by two trips there. The first was in 1925, and the second was a much longer stay (approximately four months) in 1927, both during the dictatorship of General Miguel Primo de Rivera. Barradas prompted Lorca’s first trip to Barcelona when he invited Lorca to give a talk at the ateneo, or athenaeum. The fact that Salvador Dalí, his friend from the Residencia de Estudiantes in Madrid, invited Lorca to spend a few days with him in Cadaqués while he was in Catalonia was surely a motivating factor to make this long journey during his spring recess from school, instead of returning to Andalusia where his family lived, as was customary.

During Lorca’s 1925 trip to Barcelona and to the Dalí family summer home in Cadaqués, which took place during Holy Week, Lorca read his play Mariana Pineda three times to audiences that Dalí and his father organized for him. Although these readings were informal, they eventually led to a performance of the play in Barcelona’s Teatro Goya two years later with Dalí in charge of set design and the talented and popular Catalan actress Margarita Xirgu in the leading role. Barcelona staged the play that Lorca dreamed of performing in Madrid. Theater companies in Madrid feared that military censors could read this text as an affront to Primo de Rivera’s regime. With this experience of staging the controversial play, Lorca discovered that the Catalans in Barcelona were more open than the powers that be in Madrid. This support was crucial for him and his confidence as a young aspiring artist. Lorca’s second trip to Catalonia was much longer, since he was there primarily to prepare for the opening of Mariana Pineda.

When Mariana Pineda opened in Barcelona on June 24 of 1927, another Catalan, Josep Dalmau, invited Lorca to exhibit twenty-four of his drawings at his gallery. By the time of this second visit to Barcelona, Lorca’s supporters there included Dalmau, Dalí, Rafael Benet, J. V. Foix, Josep Carbonell, M. A. Cassasayes, Lluís Góngora, Regino Sainz de la Maza, Lluís Montanyà, Joan Gutiérrez Pili, and, of course, Sebastià Gasch. According to Lorca, his main attraction to Barcelona was his friends, as he notes in a letter to Gasch, “Barcelona me atrae por vosotros” (I am attracted to Barcelona because of you all).29 We can be sure that Lorca loved his friends in Catalonia. Lorca spent the month of July in Cadaqués with the Dalí family, the same month that an experimental piece of prose written by Dalí, “San Sebastián,” dedicated to Lorca, was published in L’Amic de les Arts. After this particular publication, Dalí became a regular contributor to this Catalan journal. Perhaps the fact that Dalí was connected to other avant-garde networks outside of Catalonia made him an attractive choice as a journalist for the editor of this magazine that supported the Avant-Garde. Using network studies terminology, then, Lorca’s ties to the Catalan Avant-Garde network were mutual, multiplex, and strong.

While Lorca remained friends with Gasch, this was not the case with Dalí. When Lorca published his poetry collection, titled Romancero gitano (Gypsy Ballads), in 1928, it received rave reviews in the press nationwide. Dalí, on the other hand, did not agree. He was greatly disappointed with the book. Dalí’s letter to Lorca, filled with stinging criticism, suggests that perhaps something else was bothering Dalí, perhaps something that could have happened between these two good friends during Lorca’s second, much longer, stay in Catalonia in 1927. Something must have sparked Dalí to cause such a mood change toward his dear friend who had been the subject and inspiration of so many of his foundational early works and who had become so close to the Dalí family. In this letter we can see how Dalí felt that Lorca committed treason with this collection of anecdotal gypsy ballads, thereby denying everything the two friends had been fighting for as avant-garde artists. With this letter, Dalí wounded Lorca for life, and it marked the beginning of the end of their close friendship.

Dejected and demoralized, Lorca retreated to his family’s rural home in Andalusia and put his pen down for almost an entire year. His parents were so worried about their son’s emotional state that they sent him across the Atlantic in hopes of brightening his spirits. Echoes of a conflicted poetic voice struggling to escape from an inferno are heard in the collection of poems that he wrote there, Poeta en Nueva York (Poet in New York). At the same time, Dalí and Luis Buñuel (another close friend from Lorca’s days at the Residencia de Estudiantes in Madrid) released their debut Surrealist film, An Andalusian Dog, without the help of their good friend Lorca. In their minds, Lorca had given the public what they wanted with his book Romancero gitano, rather than stay true to the Avant-Garde spirit. But Lorca had that extraordinary human quality: the ability to overcome and make the best of things. When he returned to Spain, he exceeded everyone’s expectations, produced his best work, and continued to befriend Catalans; one of the strongest examples being that of the talented actress Margarita Xirgu, who continued to collaborate with him on stages worldwide.30 Even so, Lorca kept his distance from Barcelona. He would not return there until September of 1935 for the opening of his play Yerma.

Other Considerations and Critical Nodes

How did the nodes of various avant-garde networks in Barcelona and Madrid identify and communicate with one another? What language did they speak? What tools did they use? Joaquim Molas, a contemporary Catalan scholar, author of one of the few more panoramic studies of the avant-garde literary movement in Catalonia, sheds some light on these questions. Molas describes the removal of boundaries between art and literature as one of the inherent characteristics of the Avant-Garde:

Las vanguardias borraron las fronteras entre las diversas formas de expresión . . . entre la pintura y la literatura . . . por su parte, los poetas, con la idea de hacer nuevas exploraciones de tipo estético, para romper con la rutina tradicional del discurso o para hacer frente a la crisis de la palabra, reforzaron la escritura con toda clase de componente gráficos, la sustituyeron por su representación plástica y, a la larga, por el propio objeto que designa.

(The avant-garde erased boundaries between different forms of expression . . . between painting and literature . . . poets did so, on their end, with the idea of making new discoveries of the aesthetic kind, to break with the traditional routine of discourse or to confront the crisis of the word, they reinforced writing with a whole class of graphic components, they substituted traditional written discourse with a plastic representation, and in the end, with the object itself that it described.)31

Avant-garde poets confronted the “crisis of language” that was so characteristic of modernism by incorporating imagery into their writing. In order to do so, the boundaries dividing art and literature were erased. Their boundary-breaking experiments in search of a new mode of representation resulted in losing the word itself. The signifiers became the signified. The poem became the image. If the breaking of formal and traditional boundaries was an inherent characteristic of the Avant-Garde, would it be a stretch to think that the actors who practiced these ideas also challenged other kinds of limits (cultural, political, linguistic, and geographic)?

If these poets were to break with the past and with traditional poetic discourse, how would they communicate? What was their common language? Throughout this period of experimentation, the poets and artists of Barcelona and Madrid often communicated with one another through a code language of images inspired by the lexicon proposed in cubism. To be fluent in the language of images allowed them to communicate effectively with all of their spiritual peers regardless of nationality or mother tongue. The grouping of these images on the printed page or on the painted canvas functioned like symbols on a map. Poets experimented with drawing, as is the case with Federico García Lorca, and artists experimented with writing, as did Salvador Dalí. To speak the language of the Avant-Garde required learning a new form of expression: one centered on the image, free of descriptions, anecdotes, sentimentalisms, and narrative. The goal was to break with the direct mimicking of reality. The Avant-Garde was fueled by a desire for rupture, especially with the bourgeois and academic models; it was motivated by research and experimentation; finally, it was concerned with sharing, or publicizing, its members’ experiments and findings of innovative aesthetic styles beyond their own networks.

Just like the poets and artists who wanted to remove the boundaries between the old and the new in literature and the arts, there was also an intention on the part of many of the actors of each city’s movement to permeate the physical boundaries that divided them politically, linguistically, and culturally. Therefore, when we define the main characteristics of Spain and Catalonia’s Avant-Garde, one key concept emerges: interconnectivity or connectedness. The Avant-Garde, arguably the most influential cultural movement of the twentieth century in Spain, with its all-star cast of artists and writers such as Pablo Picasso, Juan Gris, Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí, Luis Buñuel, and Federico García Lorca, was the result of an intended and, in some cases, achieved communication, collaboration, contact, and networking with others who shared these actors’ beliefs in the same kinds of new ideas. One of the aspects of being avant-garde in Spain was crossing over and entering new territories in art, literature, politics, and culture with an enthusiastic spirit. Oftentimes it also involved crossing geographical boundaries, thus forming a complex series of networks connecting the various groups. Communication across borders may not have been the motivation of their art, but it was certainly a consequence. It also was a mode of survival, since the Avant-Garde was a minority movement.

A good number of the protagonists of the Avant-Garde in Spain traveled to Barcelona or Madrid to meet, work with, befriend, and, in some cases, collaborate with their spiritual peers. Some of these individuals were native to either Barcelona or Madrid, but others were (originally) from places as diverse as Irún in the Basque Country, Palafrugell in the interior of Catalonia, or Montevideo, Uruguay. Nevertheless, these cultural nomads resided in Barcelona or Madrid at one point or another. They were all visitors to or residents of either Madrid or Barcelona, and they all made it a point to meet their peers while visiting the other city. Generally, the purpose of the contact between these artists and writers was for them to learn about the other and return to their respective local networks and disseminate news. We can call this behavior “networking.” Their trips, contacts, friendships, exhibits, and projects all play a fundamental role in understanding the essence of the origins and development of Spain’s dynamic Avant-Garde moment. To overlook these contacts would result in a distorted view and incomplete understanding of the cultural movement as a whole.

Federico García Lorca and Salvador Dalí stand as the two best-known bridge figures, or nodes, involved in the cultural networking between Barcelona and Madrid, but they were not the only ones.32 Even though they are often treated as exceptional cases, Lorca’s activity in Catalonia and Dalí’s pursuits in Madrid are emblematic of a mode of conduct that was inherent to the Avant-Garde in Spain and Catalonia. In order for their communication to be effective, they had to speak the same language of the Avant-Garde, as well as share a similar spirit and network. In the case of Lorca and Dalí, we know they first met in Madrid as students at the Residencia de Estudiantes, where they both lived. Neither one was a native of Madrid. Lorca was from the south of Spain (Andalusia) and Dalí from the north (Catalonia), but they shared all of the three aforementioned qualities: aesthetic language, spirit, and networks. It is not surprising that they became so close.

If we look at the specific case of this friendship, we will find that they collaborated, traveled, performed, and published together. Because of their relationship, the distance between Barcelona and Madrid was greatly reduced. But the Lorca-Dalí link is just one within the much larger cosmos of Spain’s Avant-Garde. Like Lorca and Dalí, lesser-studied writers like Luis Bagaría, Rafael Barradas, Ernesto Giménez Caballero, Joan Salvat-Papasseit, and Sebastià Gasch formed friendships that bridged gaps dividing Barcelona and Madrid. As a result of these relationships and the networks they generated, the ideas that sprang forth from these individuals traveled across cultural, geopolitical, and linguistic borders. Together, they formed a larger network of a human system with the unified goal of combating tradition while creating new modes of representation. Their desire and ability to permeate boundaries through traveling, writing, painting, publishing, and networking were crucial to the development of improved communication between the artistic and literary networks of Barcelona and Madrid. Unfortunately, the way the Avant-Garde in Spain has been documented and described over the last century has made it challenging to determine the relationships that made up this overall network connecting Barcelona and Madrid.

Another famous bridge figure who connected Barcelona and Madrid but who predates Lorca and Dalí is one of the original initiators of the European artistic avant-garde movement, Pablo Picasso (Malaga, 1881–1973). Picasso lived a comfortable middle-class life in Andalusia until his father took a post in the city of La Coruña in the northern region of Galicia, Spain, as an art professor in 1891. Four years later, Picasso’s only sibling, Conchita, died of diphtheria, and the family moved to Barcelona. His father enrolled his only son at the Llotja School of Fine Arts in Madrid, where he visited El Prado Museum frequently. Two years later, Picasso presented his painting Science and Charity at the Fine Arts General Exhibition in Madrid, and he was accepted to the San Fernando Academy of Fine Arts. After falling ill with the scarlet fever, he returned to Barcelona. On the invitation of his friend Manuel Pallarès, he moved to Horta d’Ebre in Catalonia for eight months. When he returned to Barcelona in 1899, he joined the artists and poets who frequented the tavern Els Quatre Gats (The Four Cats), a meeting place of modernists. This group of artists shared close ties to the Parisian symbolists. By associating himself with this group of painters and intellectuals, he was inherently rejecting the academic style of painting of his father. In 1900 he had his first solo show at Els Quatre Gats, consisting of 150 modernista-style portraits with an art nouveau influence. These small pictures depicted his Catalan friends and other leading figures like Ramon Casas, Santiago Rusiñol, Miquel Utrillo, and Pere Romeu, who happened to be the four founders of the club.33 That same year Picasso made his first trip to Paris, where he attended the Universal Exhibition. He spent Christmas in Barcelona and the New Year in Malaga before moving to Madrid, where he intended to stay for one year.

During this second stay in Madrid in 1901, Picasso founded a small journal named Arte Joven (Art of the Youth) with his Catalan friend Francesc d’Assís Soler, which ran five issues. He returned to Barcelona, followed by a second trip to Paris, where he showed sixty-three works alongside the Basque painter Francisco Iturriño in the gallery of Ambroise Vollard. He returned to Barcelona, and in 1902 took a third trip to Paris, where he lived and worked with the symbolist writer Max Jacob. In 1903 he went back to Barcelona and in 1904 moved to Paris indefinitely. Picasso’s work from 1901 to 1903, known as the Blue Period, reflects the major changes he was going through as a young man looking for his way as he worked feverishly and traveled back and forth between various cities, especially Barcelona, Paris, and Madrid.

A recent art show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City displayed the Picasso works in the museum’s permanent collection (thirty-four paintings, fifty-eight drawings, a dozen sculptures and ceramics, along with two hundred of the museum’s four hundred prints). This show emphasized the importance of Picasso’s early friendships with Catalans, especially with Pedro Mañach, Jaime Sebartes, Ricard Canals, and Carles Casagemas. One of the important results of these friendships was an easier transition to Paris. In Barcelona, Picasso found a network of like-minded individuals centered at Els Quatre Gats tavern, something that was harder for him to find in Madrid but that he was willing to create with the attempt of founding a small journal with his Catalan friend Francesc d’Assís Soler. Barcelona was where the Picassos had their home, the place he would always call home after many of his trips, his headquarters, a cultural center that was open to change. Then, at the age of twenty-three, in the spring of 1904, he took a leap of faith. He left behind the comfort and security of Barcelona and moved to Paris permanently. This was the artistic capital of the world and a major avant-garde center. Soon thereafter, Picasso became a critical node in Paris for the young artists and writers of Spain who aspired to follow his lead.

The complexity of describing a node and the nature of communications between one node and another can be seen in the case of one of the leaders of the Madrid avant-garde network: Ramón Gómez de la Serna (Madrid, 1888–1963). No history of the avant-garde movement in Madrid is complete without including him or his work. The filmmaker Luis Buñuel considered him (not Dalí, Picasso, Miró, or Lorca) to be “the man who most influenced our entire generation.”34 Even today, he stands as one of the only Madrid natives ever to be mentioned in Catalan literary histories.35 He is also one of the few Madrid-born poets who published in the Barcelona avant-garde press, even though it was not very often. Gómez de la Serna is considered by many to have founded the Avant-Garde movement in Spain (not Catalonia) when he published a translated version of F. T. Marinetti’s first futurist manifesto in his monthly periodical, Prometeo (Madrid, 1908–12).36 As a result of his correspondence with Marinetti, over the course of a year, the Italian futurist wrote a manifesto specifically addressed to Spaniards that appeared in Gómez de la Serna’s journal, Prometeo (no. 20, 1910), but nowhere else in Spain, not even Barcelona. Gómez de la Serna enthusiastically supported this radical way of writing poetry, inspiring him to publish more of his experimental poems, which he called greguerías. For Gómez de la Serna, Italian futurism represented a new kind of literature that had nothing in common with the introspective and overly emotional writings of the Generation of ’98 authors or the extravagant poetry of modernista writers. Italian futurism was liberating. It dismantled boundaries of representation and freed the word from all its previous constraints in an original way. Yet Marinetti’s ideas did not stick in Madrid, while in Barcelona, Italian futurism found much greater resonance.

Even though Ramón (as everyone called Ramón Gómez de la Serna) visited Barcelona only once, and only briefly, he fostered significant ties with Catalans from his headquarters in Madrid.37 He formed and maintained many relationships with individuals from all corners of Spain and throughout Latin America and Europe. Besides being a tireless letter writer, he was also the editor of a magazine, a frequent contributor to the press both in and outside of Madrid, the leader of a popular literary club, a public speaker, and inventor of the catchy greguería—brief, image-based metaphoric lines of prose usually involving humor. His capacity to weave so many intricate webs between people from all walks of life was the result of his untiring, creative, and charismatic personality, in addition to his unbreakable faith in the Avant-Garde. Gómez de la Serna mediated the flow of information within the Madrid avant-garde network through his various activities, especially the weekly social gathering he hosted, without ever spending much time away from Madrid and without becoming a core member of any other avant-garde network. Other avant-garde actors from Spain and Catalonia came to him, not the other way around. People referred to him as “the Pope,” and to his literary gathering place, discussed more in depth later, as “the Sacred Crypt” or “the Tabernacle.”

Even though Gómez de la Serna did not visit Barcelona until 1930, he was still connected to the avant-garde network there. In order to determine the nature of his relationship to the Barcelona avant-garde network, it would be useful to examine two of his strongest links: first, his contributions to the Catalan-language press, and second, his role as the leader of the well-known Pombo tertulia, or literary gathering. Members of the first avant-garde circles of Barcelona probably initially heard about Gómez de la Serna as the first in Spain to publish Marinetti’s futurist manifesto, in his Madrid-based periodical Prometeo. Gómez de la Serna initiated a correspondence with Marinetti that resulted in the latter writing a special manifesto addressed exclusively to Spaniards that was published in the same magazine the following year.38 Gómez de la Serna was one of the first writers from Madrid to take a serious interest in Marinetti. Avant-garde enthusiasts in Barcelona keeping up with Madrid’s press (e.g., Prometeo) would have taken note.39

Rather exceptionally, Gómez de la Serna was one of the few representatives of Madrid’s small avant-garde network who published in Barcelona’s press, and he did so in two of the key Catalan avant-garde journals, namely Un enemic del Poble (Barcelona, 1917–19) and Hèlix (Vilafranca del Penedés, 1929–30), both of which were primarily Catalan-language periodicals. He was one of the only Madrilenians to publish in Joan Salvat-Papasseit’s two-page “subversive sheet,” Un enemic del Poble, even if it was only on two occasions.40 Much later, Hèlix published Gómez de la Serna’s work alongside that of other Spanish writers, such as the novelist Benjamín Jarnés, Ernesto Giménez Caballero, and the journalist Ledesma Ramos. His contributions to both Un enemic del Poble and Hèlix were printed in Spanish. Outside of these two exceptional cases, Gómez de la Serna’s work can also be found in almost every other city and town in Spain that had an avant-garde periodical. The exact link between Gómez de la Serna and the Barcelona avant-garde remains a mystery. One possible connection could have been Marinetti, who visited and maintained contact with avant-garde enthusiasts in both Barcelona and Madrid. Another possible connection could have been through the Catalan journalist Josep Maria de Sucre.

Josep Maria de Sucre (Barcelona, 1886–1969) was a member of the Catalan avant-garde network who visited Madrid during the period in question (approximately 1909–29). Younger than the Catalan futurist Gabriel Alomar, and a good friend of the established modernista poet Joan Maragall, Sucre was a government worker, poet, painter, art critic, journalist, and curator. For twenty years, from 1903 to 1923, Sucre’s day job consisted of documenting criminals for the city government of Barcelona. His early books, all written in Catalan, include Un poble d’Acció (1906), Apol-noi (1910), Joan Maragall (1921), L’ocell daurat (1922), and Poema barber de Serrallonga (1922). His Spanish collection of poetry, Poemas de abril y mayo (1922), caught the attention of Joan Salvat-Papasseit while convalescing in a tuberculosis sanatorium near Madrid. After meeting the Barcelona art gallery owner and collector Josep Dalmau in 1920, Sucre’s painting flourished. He exhibited in Dalmau’s Galleries on three occasions.41 He also helped Dalmau organize several exhibitions, such as Ernesto Giménez Caballero’s literary posters (January 1928) and the Homage to Rafael Barradas (August–September 1928). Another one of his contributions was organizing the banquet to celebrate the opening of Lorca’s exhibition of twenty-four drawings at the Dalmau Galleries (1927). As an art critic, Sucre wrote numerous catalog introductions and reviews of art shows, in addition to making introductory speeches during art openings.

Sucre’s first trip to Madrid was in 1910, and although the motive for his visit and the length of his stay are unknown, it is a fact that he met Gómez de la Serna while he was there. As president of the Ateneu Enciclopèdic Popular of Barcelona (1912–15), Sucre organized a cultural excursion from Barcelona to Madrid, including visits to Toledo and the Escorial. The theme of the 1914 trip was the Renaissance artist El Greco, and it is possible that he met up with Gómez de la Serna again while he passed through Madrid. According to Sucre’s memoirs, he attended the opening of Pombo as a literary club that took place in 1915.42 Almost a decade after his first visit to Madrid, Sucre published a poem dedicated to Gómez de la Serna in the last issue of Salvat-Papasseit’s Un enemic del Poble (no. 18, May 1919). Written in Catalan, the poem takes the reader on a virtual tour of Madrid’s cultural landmarks, including Gómez de la Serna’s Pombo Café. Sucre is one of the few Catalans associated with the Barcelona avant-garde network who visited Madrid on several occasions, met Gómez de la Serna, befriended him, and possibly facilitated publishing his work in Barcelona. Sucre maintained a sustained working and publishing relationship with the writers in Madrid up until approximately 1929, when he published his last of many articles in La Gaceta Literaria (Madrid, 1927–32).43 His articles appear in this periodical, one of Madrid’s strongest supporters of the Avant-Garde movement, from beginning to end. Sucre functions as a node connecting the avant-garde networks of Barcelona and Madrid because of his friendship with Gómez de la Serna, but also because of his later collaborations in the cultural press of Spain and abroad, writing in both Spanish and Catalan.44

Sucre began his career under the influence of modernisme, frequenting Els Quatre Gats, Barcelona’s famous modernista meeting place for revolutionary, anti-bourgeois painters like Pablo Picasso and Joaquim Sunyer. Most critics agree that Sucre abandoned his modernista tendencies around 1910 or 1911. His aesthetic and ideological turn from the neo-romantic to the avant-garde may very well have been directly related to his 1910 trip to Madrid, where he met Gómez de la Serna, who had recently translated and published the first Italian futurist manifesto. The year that Sucre and Salvat-Papasseit met is unknown, but it could not have been too much after his third trip to Madrid in 1915. The first letter to Sucre included in Salvat-Papasseit’s correspondence is dated December 1917. Interestingly, in this postcard, Salvat-Papasseit explains why he and Sucre could not visit Barradas, who had promised to paint a portrait of Sucre. If Barradas was planning on painting a picture of Sucre, he must have been a close friend or, more probably, Sucre was one of the Catalan avant-garde network nodes who also happened to be connected to Madrid.

Further research shows that Sucre and Salvat-Papasseit collaborated on several projects as they both experimented with notions of the Avant-Garde. For instance, Sucre wrote the prologue for Salvat-Papasseit’s posthumous essay collection, Mots propis (In My Own Words) (1917–19). Sucre left Els Quatre Gats to join a new circle of friends that included Salvat-Papasseit, Barradas, and Torres-García. After 1925, he regularly attended Barradas’s literary gathering in the outskirts of Barcelona every Sunday. He was one of the group’s core members. He wrote about Barradas’s influence and importance within the modern art movement on multiple occasions, from various platforms, and in both Spanish and Catalan. By the end of the 1920s, he was one of Madrid-based La Gaceta Literaria’s main correspondents in Barcelona, just as he was for Alfar out of La Coruña in Galicia. His main responsibility at La Gaceta Literaria was to review new Catalan books.

If we describe the links between Gómez de la Serna and the Barcelona network using network terminology, we can also describe the nature of the relationship between these various nodes. In the case of Un enemic del Poble, the link seems unidirectional. Gómez de la Serna may have been connected to Barcelona through Sucre’s early visit to Madrid (1910) and their subsequent friendship. Gómez de la Serna published in the Catalan periodical with which Sucre was associated (February and May 1918), but did Gómez de la Serna reciprocate by publishing the magazine’s editor, Salvat-Papasseit, in Madrid? Was it Gómez de la Serna who informed the other avant-garde actors in Madrid of this Catalan avant-garde poet who was founding avant-garde periodicals and publishing books of poetry inspired by Italian futurism? Is there symmetry in this link? In the face of so many questions left unanswered, the frequency of the tie between Gómez de la Serna and Salvat-Papasseit is not very strong, since the work of Gómez de la Serna only appeared in two of the eighteen issues of Un enemic del Poble and no where else, until ten years later in a journal published outside of Barcelona. However, we must also keep in mind that the period between 1918 and 1929 was also the period of the Primo de Rivera dictatorship in Spain (1923–30), when relationships between the avant-garde networks of Barcelona and Madrid became estranged.

Gómez de la Serna was one of the few Madrid experimental poets to publish in the Barcelona avant-garde press, but seen from the other direction, the first person to publish him in the Barcelona avant-garde press was also one of the founders of the Catalan literary avant-garde movement: Joan Salvat-Papasseit (Barcelona, 1894–1924). It was his intention to use Un enemic del Poble (1917) as a platform to publish the experimental work of others outside of Barcelona, regardless of their nationality, so long as they spoke the same language of the Avant-Garde. Salvat-Papasseit, however, was not concerned with creating any sort of new nation, vanguardist or otherwise, based on some sort of common spirit. Just one year prior to the publication of the first issue of Un enemic del Poble, another group of poets in Barcelona was already incorporating and practicing the lessons they learned from the Italian revolutionary poet, Marinetti, in 1909. With the added influence of dadaism, an artistic and literary movement created in Zurich in 1916 that responded directly to the atrocities of World War I, and exposure to the experiments of French exiled avant-garde artists who practiced these radical poetic philosophies and forms of expression, like Francis Picabia, the Catalans were the first in Spain to found literary journals strictly devoted to promoting these new styles (e.g., Troços, 1916, directed by Josep Maria Junoy).

Poets like Junoy and Salvat-Papasseit were instantly attracted to Marinetti’s “words in freedom” and futurism’s goal of increasing the expressivity of language through the minimization of adjectives, adverbs, finite verbs, and punctuation. Also interesting for these Catalan poets were the onomatopoeia and typographical experimentation proposed by futurism. After founding three avant-garde magazines (some of the first in Catalonia and Spain) and publishing several books of experimental poetry, such as Poemes en ondes hertzianes (1919), Salvat-Papasseit published the “First Manifesto of Catalan Futurism” (1920), which he signed: “poetavanguardistacatalà,” or Catalan-avant-garde-poet. Four years later, his plans to revolutionize Catalan poetry were cut short.45 Tuberculosis took the poet’s life at the age of thirty.

Joan Salvat-Papasseit is an exceptional case for the concerns of this study, because he was a figure who strongly linked the Barcelona and Madrid avant-garde networks through a series of publications. His futurist-inspired poetry appeared in three of the foundational avant-garde literary journals from Madrid: Grecia (1920), Ultra (1922), and Tableros (1922). The poems in Grecia stand out because they are in Spanish. When a group of poets writing in the Madrid-based Ultraísmo style were seeking inspiration, they turned to Barcelona and found Salvat-Papasseit. This young, revolutionary poet spoke the language that both avant-garde centers could understand. One of the greatest lessons Salvat-Papasseit learned from Italian futurism was finding meaning in the sounds and shapes of words. He understood that with typography, he could create the grammar for a more universal language. Poetry had a visual component just as much as the visual had a poetic element. He was in the process of constructing this language and developing his voice when his illness worsened, at which point he took a quick detour toward a more traditional and sentimental style of poetry.