Chapter Four

One Hundred Little Magazines

Substantial proof that members of avant-garde circles in Barcelona and Madrid were well aware of one another lies within the pages of over one hundred small-circulation periodicals, more commonly known as “little magazines.” Many of these publications are art objects in and of themselves, for it was in their nature to be everything that commercial publishing was not. In Spain, they came in all shapes and sizes. Editors of the little magazines published poems alongside drawings, arranged for illustrated covers, printed on a variety of paper textures, and experimented with color printing and new fonts. Unfortunately, since many of these periodicals did not have consistent financial backing, most of them were short lived. Some editors managed to publish only one issue of their periodical. Others succeeded and were in print for years. Some little magazines were smaller than others, while others were far from little. For example, Ramón Gómez de la Serna’s monthly Prometeo (Madrid, 1908–12), the periodical to first report the news of Italian futurism in Madrid, averaged about one hundred pages per issue.

In Catalonia, literary reviews played an important role in what Robert Davidson calls “the consolidation of Catalan culture.”1 In Barcelona, especially, there was an artistic and literary journal for every taste (e.g., modernisme, noucentisme, futurisme), as well as publications associated with a variety of political groups (e.g., anarchists, communists, traditionalists). The function of these Catalan publications went far beyond reporting news. As Joan Ramon Resina puts it, they “took the ostensible public role of modernizing culture.”2 Writing about the little magazines in 1930, Ezra Pound believed that the history of contemporary literature is contained within the pages of these magazines. The motivation to produce and sustain these publications was a combination of creating, documenting, debating, and modernizing contemporary culture. Without these periodicals, it would be difficult to imagine how the Avant-Garde could have thrived.

Matthew Luskey notes how culture is formed within the pages of the small-press periodicals, in which social, political, material, and economic forces interconnect.3 In the case of the periodicals directly related to the Avant-Garde, “[They] functioned as brief yet defiant public spheres, promoting vanguard movements and providing forums for their initial reception of an artist’s works.”4 While Luskey refers to the Avant-Garde in the United States, the same can be said for the movement in Catalonia and in the rest of Spain. The homepage for the Little Magazine Collection at the Memorial Library at the University of Wisconsin offers another reason why these texts are so fundamental for the study of early twentieth-century culture:

Little magazines have continuously rebelled against established literary expression and theory, demonstrating an aggressive receptivity to new authors, new ideas, and new styles . . . Little magazines have sponsored or introduced all of this century’s literary trends, including imagism, dadaism, surrealism, symbolism, and the Beat generation. They were also the first to publish and discuss the artistic and literary manifestations of socialism, psychoanalysis, and Marxism and other social movements.5

Even though the collection at Madison is centered on English-language periodicals, this summary can also be used to describe the role of little magazines in Spain. In particular, the little magazines in Barcelona and Madrid were aggressively receptive to new authors, new styles, and new ideas. They were also some of the main instruments for sponsoring and introducing the century’s new trends. Additionally, the majority of the little magazines from Barcelona and Madrid showed an explicit interest in connecting with other periodicals and other centers of cultural production that shared the same spirit or mission as their own publication. This final point especially supports the main argument that drives this book: the Avant-Garde as a movement in Spain functioned as a system of networks that connected people, ideas, and artifacts.

Over one hundred periodicals dedicated to art, literature, and culture from 1900 to 1936 were consulted in the periodical archives in both Barcelona and Madrid, in special libraries known as hemerotecas, to compile the evidence for this book. Many more periodicals pertaining to this period remain to be discovered and studied in detail. Most of them do not have facsimile editions, and many are not available in full sequence. With the progress of today’s internet age, more and more of these periodicals are becoming available online and can be accessed virtually through library Web sites. Many of these documents were censored or destroyed during the Spanish Civil War and during the subsequent dictatorship of General Francisco Franco. For the most part, scholars did not have access to these texts until after Franco’s death (1975). Some of the consulted periodicals for this book have been very well documented; others have rarely been considered in relation to the Avant-Garde in Spain. Given the available archival material over the last five years, this search involved discovering links between the artistic, literary, and political worlds of Barcelona and Madrid, if any.

Returning to the discipline of social networks, one could potentially create a graph or map showing how many of the little magazines of Barcelona and Madrid were related to one another. One would start by analyzing the nature of connections between nodes: editors, illustrators, journalists, advertisers, and other contributors. The relational ties connecting these nodes would reveal an elaborate network, matrix, or web. Since there were so many little magazines from the specific period in question (focused mostly in the period from 1909 to 1929), this task would be a project in and of itself. To create such a graph, chart, or map is not the intention here. Instead, the goal is to draw attention to several key periodicals from this vast editorial universe that were critical in connecting the artistic and literary avant-garde networks of Barcelona and Madrid.

It quickly became clear that the little magazines from these two cities did not exist in a vacuum. They were naturally linked to other periodicals within their own cities, and in most cases, they were connected to periodicals outside of their own city of origin. On one level, writers and artists were often the people who were most responsible for establishing these links. Going back to the Catalan art critic and avid Avant-Garde supporter, Sebastià Gasch, he started contributing to periodicals in Barcelona, then in Madrid, followed by other cities in Spain, and later in the Latin American press (e.g., Atlántico). The little magazine was the platform from which many friendships and relationships formed and evolved. They functioned as the heart of the literary and cultural Avant-Garde movement in Spain, and most of them, but certainly not all, were published in Barcelona and Madrid. They played a leading role in receiving and divulging avant-garde ideas in Spain and Catalonia, as well as maintaining the networks that sustained them.

The little magazines from Barcelona and Madrid share many similar qualities. They include poetry, reviews, editorials, essays, illustrations, and forums for criticism. They confront readers with new ideas that challenge tradition and the status quo. For the most part, those who contributed to the little magazines were united by a common Avant-Garde spirit, or, in the words of Ezra Pound, some sort of “binding force.”6 It is for this reason that when a periodical launched its first issue, its editors printed a statement of purpose, often adopting the kind of language and tone found in the artistic and literary manifestos so closely tied to the Avant-Garde movement; these mission statements were often located on the first page of the first issue of the periodical. Very few little magazines went to press without publishing such a declaration. Oftentimes the editor penned this mission statement, but sometimes a highly regarded member of the intellectual community, such as José Ortega y Gasset or Miguel de Unamuno, would be asked to write it. Other times, the text was anonymous, perhaps for fear of recrimination during times of censorship.

Overall, the little magazines from Barcelona and Madrid shared very similar functions. Their goal was to discover new voices that spoke to the moment and that perpetuated the Avant-Garde spirit. Usually, this voice was in the form of poetry, but it was also expressed in prose. This message was also expressed visually with illustrations or in the periodical’s layout and design. The vanguard style had a distinctly modern look and new voice that clearly distinguished it from more traditional periodicals. In contrast to the immediacy of a newspaper, the weekly, bimonthly, or monthly journals called for pause and reflection. Their objective was to disseminate information about art, literature, and culture that resonated with the mission of their program, as stated in the first issue, while building a network of supporters in the process. Their function was cultural, social, intellectual, and, in some cases, political. Many of these periodicals published lesser-known writers or works that would never be considered in commercial or more conservative publications. The vanguard magazines not only introduced new literary and aesthetic theories, usually exported from abroad, but they put these new ideas to practice in the form of poetry, prose, illustrations, and the design of the overall journal. The little magazines are one of the most valuable resources for understanding the Avant-Garde movement throughout Europe, the United States, and Latin America.

In my search for understanding the kinds of relationships that connected avant-garde Barcelona and Madrid, three major patterns emerged. First, I discovered a clear intention to dialogue that predates the arrival of the Avant-Garde in Spain and Catalonia (1904–9). Second, with the arrival of the first European avant-garde movements (1909–23), there was an increase in communication and a greater emphasis placed on intercultural communication across geographical, social, and political lines. Third, a major shift occurs in the mid-twenties (1923–29), when avant-garde periodicals begin to appear mostly in areas outside of Barcelona and Madrid. This chapter deals with these three stages of development in the construction of this networking platform between Barcelona and Madrid, and how it informs our overall understanding of the Avant-Garde in Spain.

As discussed in the previous chapter, at the turn of the twentieth century, most Spanish intellectuals and politicians were preoccupied with the regeneration of Spain following the colonial Disaster of 1898. A number of periodicals from this period demonstrate a clear attempt to dialogue with one another, or have as their mission the goal of gaining greater mutual understanding between Barcelona and Madrid in particular. Some of these periodicals published in Madrid clearly state that their mission was to achieve a greater “spiritual unity” between the various regions of Spain. With the introduction of futurism in Spain in 1909, a second pattern emerges amongst the cultural press that lasts until the end of the First World War. Poets in Barcelona, inspired by Italian futurism, Swiss dadaism, and French literary cubism, experiment with these new ideas from abroad with enthusiasm. Writers in Madrid, on the other hand, were still looking inwards. It is not until a group of poets who were gathered in Madrid invented their own avant-garde style, Ultraísmo, in 1919, that we see the first steady signs of experimentation sparked by the European avant-garde movements within the pages of the journals published in Madrid. By this late date, the excitement of futurism, dadaism, and literary cubism had fizzled in Barcelona. By 1923, experimentation with these new poetic and artistic styles came to a sudden halt with the military takeover of General Miguel Primo de Rivera. The effects of this dictatorial regime are reflected in the small-circulation periodicals in numerous ways. This date marks the beginning of the third stage in the study of the literary and cultural press, in which direct connections between Barcelona and Madrid diminish to the point of almost disappearing. Instead, a significant number of avant-garde periodicals from other cities in Spain establish connections by circumventing or avoiding Barcelona and Madrid altogether.

Much work remains to be done in the hemerographic study of the Avant-Garde in Spain.7 I am not the first to make this assertion. For one, Juan Manuel Bonet, the contemporary literary and art critic, as well as the once-director of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia (MNCARS) in Madrid, and prior to that of the Insitut Valencià d’Art Modern (IVAM) in Valencia, has already made this point. He has identified the lack of study of the little magazines as one of the most “obtrusive lacunae” preventing us from gaining a greater understanding of this cultural moment. At the beginning of the introduction to his indispensable dictionary of the Spanish Avant-Garde (1995, first edition), he admits to his lack of knowledge about the Catalan avant-garde as a major obstacle: “[C]onfieso que donde más dudas he tenido, ha sido en el ámbito catalán” (I confess that where I have had the most doubts [in compiling this dictionary], has been in the area of Catalonia).8 Similarly, after a long career devoted to documenting the literary and cultural press of the Spanish Avant-Garde, Rafael Osuna, in his latest book, Revistas de la vanguardia española (2005), rallies Hispanists to continue hemerographic research of the historical Catalan press:

Mucho tememos que la fogosidad investigadora y crítica de que hoy goza la vanguardia conozca un decaimiento en el futuro, a menos que se propongan nuevas avenidas de investigación, como pueden ser las conexiones con las vanguardias francesas e italianas—no con telescopio como casi siempre hasta ahora, sino microscópicamente—, sin olvidar la catalana, ésta última por ser, no sólo muy fecunda, sino parte esencial de nuestro mundo cultural; esta ampliación de miras nos haría también redirigir un orbe más universal esos afanes localistas, regionalistas o nacionalistas que hoy se observan.

(We greatly fear that the eagerness of the research and criticism about the Avant-Garde today will experience a decline in the future, unless new avenues of investigation are proposed, like those seeking connections between the French and Italian vanguards—not with a telescope as it has been approached until now, but with a microscope—, without forgetting the Catalan avant-garde, because not only is it plentiful, but it is also essential to our cultural world. This widening of scope would also redirect our world to one that is more universal beyond the local, regional, and nationalist zeal that can be observed in the criticism and research of today.)9

This book serves as an initial attempt to bridge some of the blaring gaps that both Bonet and Osuna describe above in their description of the relationship between the Catalan and the non-Catalan early twentieth-century vanguard in Spain. Specifically, my focus is on defining and studying the connections between artistic, journalistic, and literary networks in Barcelona and Madrid. While I have consulted a wide array of primary sources (e.g., literary almanacs, poetic anthologies, artworks, illustrations, letters, maps, memoirs, museum exhibit catalogues, photographs, and other literary and visual texts), much of the evidence I use to describe the system of networks connecting avant-garde Barcelona and Madrid comes from small-press periodicals. After consulting these archival documents from Spain, France, Italy, England, Switzerland, and various North and South American countries, it is abundantly clear that a relationship between Barcelona and Madrid did indeed exist—even if that means that sometimes they intentionally ignored one another.

Stage 1: Consensus (1904–9)

Renacimiento (Renaissance) (1907) was the first twentieth-century periodical printed in Madrid to regularly feature Catalan writers and artists. Although this cultural magazine predates any sort of avant-garde activity in Spain, its editor, Gregorio Martínez Sierra (Madrid, 1881–1947), would become one of the leaders in the renovation of Spanish theater in his role as playwright and director. For example, Martínez Sierra was the first director to offer the young Federico García Lorca the opportunity to stage his first play, El maleficio de la mariposa (The Curse of the Butterfly) (1920), at the Teatro Eslava in Madrid. From the earliest stages of his career, Martínez Sierra proved to have an open mind toward Catalan literature and culture, in the same way that he would be open to radical ideas proposed by the Avant-Garde.

Each issue of this monthly magazine totaled over one hundred pages. In other words, there was nothing “little” about it.10 Under the modernist banner of “art for art’s sake,” or in Martínez Sierra’s words, “¡Vivimos por la belleza!” (We live for the sake of beauty!), the magazine’s objective, as stated on the first page of the first issue, was for readers to discover the newest modernist poetry written in Spain in any language. Besides including poems by Juan Ramón Jiménez and the Machado brothers, the inaugural issue also included work by the leader of modernisme, the modern Catalan poetry movement, Joan Maragall (Barcelona, 1860–1911). Renacimiento published one of his poems in Castilian (“La Hazaña” [The Heroic Deed]), accompanied by an article by the Spanish-speaking poet and literary critic Enrique Díez-Canedo, who was born in Badajoz, Spain, and lived in Barcelona before moving to Madrid, and who also worked as a translator.11 The appearance of this article by Díez-Canedo, someone who lived in both Barcelona and Madrid, suggests that he is a probable link between Joan Maragall in Barcelona and Gregorio Martínez Sierra in Madrid. He also was likely the one who was able to connect what each of these two men represent—the Madrid and Barcelona cultural and intellectual elite and their respective notions of modernism. In the same issue, Martínez Sierra also published a poem written by the Catalan modernist painter Santiago Rusiñol, also in Castilian (“Cigarras y Hormigas” [Cicadas and Ants]).12 It is important to note that Renacimiento had its main office in Madrid, but it also had a satellite office in Paris. Anchoring his magazine in both Madrid and Paris allowed Martínez Sierra to feasibly connect the cultural worlds of both of these cities. By reaching out to Paris, he connected with Spanish expatriates living in the French capital. It was also a likely attraction for his Catalan contributors and potential readers, who have a history of strong ties linking them to Paris. Martínez Sierra appreciated the beauty of the works by Maragall and Rusiñol, which is why he brings these two Catalan poets to light in this first issue of his Madrid and Paris-based periodical, but he made the editorial decision to print them in Spanish, rather than in their original Catalan.

After Renacimiento published a Spanish article by the Catalan writer Gabriel Alomar (September 1907, and continued in November 1907) titled “Futurismo” (Futurism), the periodical took a radical step. Martínez Sierra published several poems in Catalan by Alomar, Joan Maragall, José Pijoan, and Josep Carner in subsequent issues (October and November 1907). According to my research, the publication of Catalan poetry in Catalan in the Madrid press was extremely rare. After the publication of Alomar’s 1907 “Futurism” article, Renacimiento printed texts written in Catalan without Spanish translations.

As discussed in the previous chapter, several years prior to the publication of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s first futurist manifesto in the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro, Alomar gave a lecture in Barcelona’s Ateneu entitled “Futurisme” (1905). He argued that Catalan autonomy and the regeneration of Catalan culture could only be achieved by adopting a forward-looking attitude, rather than reviving the past, an idea promoted by the nineteenth-century Catalan Renaixença movement. In response to Alomar’s 1905 Barcelona lecture, the editor Ignasi Folch published the first issue of the Catalan magazine Futurisme, subtitled Revista Catalana, in Barcelona (June 1907). The future of Catalan identity, culture, and independence depended on writing, speaking, and publishing in Catalan today, in the present moment. Ignasi Folch showed his support of Alomar’s futurism by publishing in Catalan.13 Interestingly, Renacimiento ceased to exist after the issue in which the Catalan poems were published (December 1907). I have not found evidence to prove that the demise of Renacimiento is a direct result of the publication of these Catalan texts, but it is a strong possibility, given the political climate. In the journal’s final issue, Martínez Sierra did not give any explanation as to why his periodical was folding. He merely stated that Renacimiento would merge with La Lectura, another literary magazine.14 While the termination of Renacimiento remains a mystery, what is clear, and most important, is that the attempt made by this periodical to forge a rebirth, renaissance, and regeneration of Spanish culture included collaboration and connection with Catalan culture.

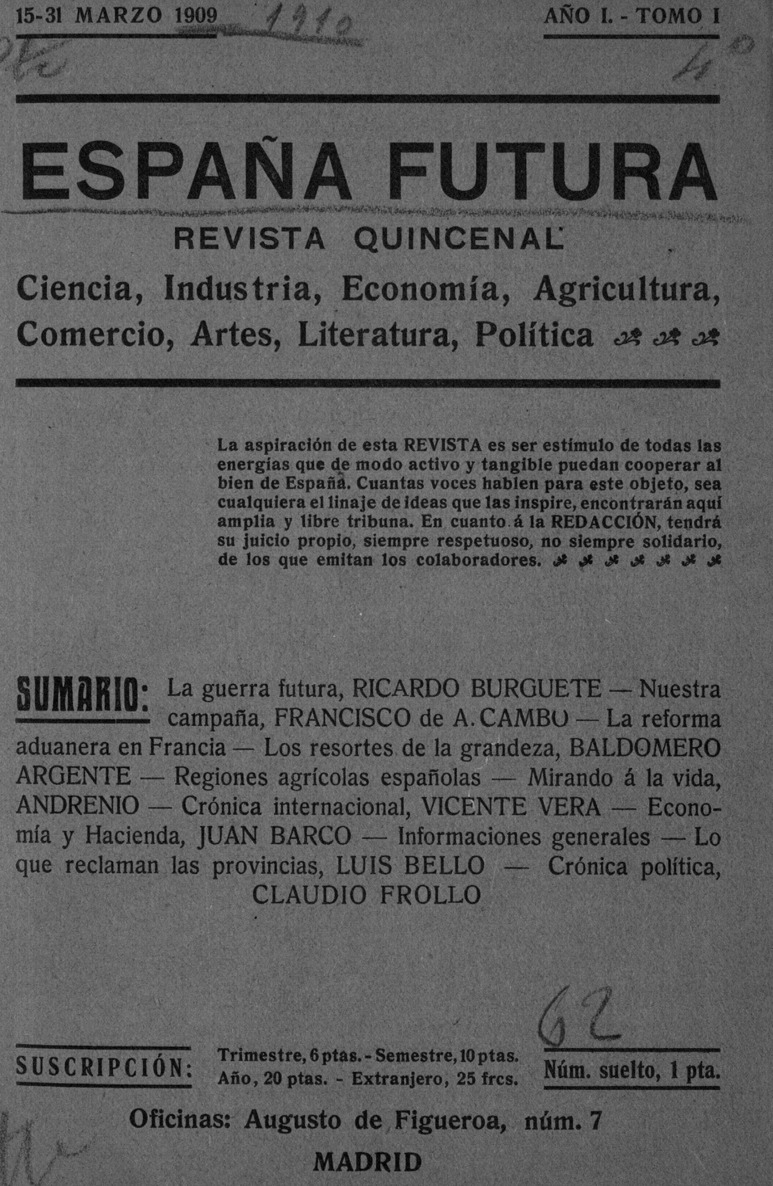

Following the futurism trail initiated by Alomar in Barcelona led me to the discovery of a small-circulation periodical that has been overlooked by most critics concerned with this movement in Spain: España Futura (Madrid, 1909–10). This bimonthly magazine is unique in that its contributors included a significant number of Catalan writers. Most of them were journalists or politicians, all writing in Spanish about topics as varied as science, business, agriculture, art, literature, and especially, politics. In the mission statement, the editors claim that the objective of their journal was to provide an open arena for dialogue with the common goal of achieving a brighter future for Spain. Once again, this “future Spain” is one that includes Catalonia. Specifically, the editor of this periodical from Madrid wanted to forge a Spanish national identity that was disassociated from the centrifugal powers of Madrid. The ideal readership of España Futura included not only those interested in art and literature, but also those involved with large industries, factories, and banks. Another way that this periodical hoped to reach a wider audience was by focusing on a different area of the country in each issue. This periodical served as a potential model for understanding between Madrid and other parts of Spain, from the point of view of business-minded people whose eyes were set on the future. Almost every issue included news from Barcelona, one of the major industrial centers of Spain, with a specific focus on its relationship to Madrid and the rest of Spain.

The wide scope of España Futura centered on an explicit interest in politics. For instance, in the inaugural issue, the editors published a speech by the Catalan politician Francesc Cambó, wherein he makes an argument for Catalonia’s autonomy.15 Printed alongside Cambó’s text, another article by the Castilian lawyer, journalist, and writer Luis Bello cautions Madrid about the dangers of ignoring the other regions of Spain, especially Catalonia. Bello recommends that Madrid, which he believes is economically weaker than other cities in Spain, should work with the Catalans, not against them. Bello points out that up until now, one of the causes of the mutual incomprehension between Barcelona and Madrid has been that all of the communication between these two cities has been stimulated by either politicians or caciques, elite landowners, rather than by intellectuals or common citizens. According to Bello, politicians and the bourgeoisie are to blame for the establishment and perpetuation of a divide between Barcelona and the rest of Spain. But with the efforts of periodicals such as España Futura, made up of mostly common citizens rather than politicians or the wealthy, this mutual incomprehension can be minimized.

Figure 4.1. Cover of the magazine España Futura.

The mission of España Futura, as stated in the first issue, was to provide an alternative to the communication initiated by politicians and the bourgeoisie by providing a more objective form of reporting for the people and by the people. The frequent news reported in this periodical about Catalans and their relationship to Madrid is noteworthy. España Futura reprinted an article by Cambó, who founded the Lliga Regionalista party in Catalonia, which would otherwise be almost impossible to access in Madrid. In a subsequent issue, Bello recounts a recent visit by Catalans to the Parliament in Madrid. According to the report, the purpose of their trip was to complain that the central state was halting their economic and political progress. They argued that Madrid moved at a much slower pace than Barcelona. Instead of focusing on the politics that motivated this visit to Congress, Bello suggests that non-Catalans in Madrid should use this encounter as an opportunity for them to learn about Catalans.

As is often the case, it is almost impossible to ignore politics when addressing the relationship between Barcelona and Madrid, or the Catalans and non-Catalans in Spain. The co-director of the periodical, Claudio Frollo, used España Futura to inform his Madrid readership about Catalonia and its potential power to build a brighter future for Spain. On several occasions, he notes that Spanish politics revolved around the axis of Catalonia, because the political influence of Catalonia was much greater than that of the rest of Spain. He argues that Catalan politics were stronger and more productive than ever, yet he insists that separatism is a mistake. His utopian vision for Spain involved the “disentanglement” of the provinces from the central powers of the state, without compromising the country’s unity:

Lo del separatismo es un error. Los catalanes todos somos fervientes españoles, y nosotros lo demostraremos con más elocuencia que nadie . . . los que protestan de nuestra conducta son los fracasados en política, los ambiciosos y los egoístas . . . nuestra política es que se entiendan unas regiones con otras para desenlazarse; que se unan, para desligarse del Poder central . . . esta es una obra de “inteligencias interregionales.”

(Separatism is an error. All Catalans are fervent Spaniards, and we will prove this with more eloquence than anybody . . . those who protest our behavior are failed politicians, the ambitious and the selfish . . . our politics is that the regions [of Spain] understand one another in order to untangle themselves; that they may unite, in order to unbind themselves from the central power . . . this is the work of the “interregional intelligence.”)16

Frollo strongly believed that if Spaniards had a more comprehensive knowledge about the specifics of the other regions of Spain (e.g., economy, industry, agriculture, architecture, literature, history), they would agree with his utopian idea of a unified but decentralized Spain. In order to educate his Spanish-speaking readership in Madrid, España Futura published a myriad of charts and graphs with pages of statistics on taxes, commerce, trade, transportation, housing, debt, and loans, thereby offering readers the quantitative tools with which they could create arguments and form opinions of their own.

Ever concerned about the future of Spain, Alomar also made a contribution to España Futura, in which he mostly agrees with Frollo’s utopian idea of a decentralized state composed of various regions. He uses the magazine based in Madrid to reassert his role as one of the first to work toward the “de-regionalization” of Catalanism, as he calls it. According to Alomar, in order to “futurize” the country, it must first be “de-regionalized.” Then, Spain can consider itself more modern and less traditional, rural, and religious. This “futurization” process was necessary for the regeneration of Spain at this moment of political and economic crisis:

Y si he tenido la pequeña gloria de improvisar esta palabra, futurismo, que ha entrado ya en nuestro léxico habitual ¿cómo no veré yo en esta revista el órgano mismo necesario al aspecto español, no ya meramente catalán, de la obra futurizante?

(And if I have the small glory of inventing this word, futurism, that has entered in our everyday lexicon, how would I not see in this periodical the same opportunity to apply it to the Spanish case, no longer just merely a Catalan one, of the work of futurization?)17

As we can see, Alomar takes credit for inventing the term “futurism,” which was making its way into the daily lexicon. As the inventor of the word and the ideology behind it, that of modernizing Catalonia, he was using the platform of this periodical to spread this “futurizing” concept outside of Catalonia, to modernize Spain as a whole. In other words, what began as a plan for the modernization of Catalonia was now being applied to Spain from the platform of Madrid’s press.

Incidentally, Ramón Gómez de la Serna published an introduction to and translation of Marinetti’s first futurist manifesto in his own periodical, Prometeo, of which he was editor, in the same month that Alomar published this article about the futurization of Spain in España Futura. Whether Alomar knew of Serna’s intentions or vice versa prior to either of these publications is unknown. What is certain is that two different concepts of futurism were circulating in the Madrid press at the same exact time: one originating in Italy and centered on aesthetics, and the other in Catalonia and focused on politics. It is also worth noting that Gregorio Martínez Sierra had already published Alomar’s two-part article on his brand of futurism in Renacimiento (September and November of 1907); also, by 1908, there were at least two other cultural periodicals in Catalonia titled Futurisme in tribute to Alomar and his new concept of futurizing Catalonia. This preoccupation with the future of Spain, especially after it lost its final colonies to the United States in 1898, was clearly shared by intellectuals both in Barcelona and Madrid during the first decade of the twentieth century. Based on the evidence found in both Renacimiento and España Futura, the construction of Spain’s future by Catalan and non-Catalan intellectuals had to include Catalan culture, language, and identity.

The Spain of the future for Alomar is one in which political power had to be decentralized and redistributed throughout the different regions of Spain. He reiterates this vision in an article titled “Las dos capitales” (The Two Capitals), published in España Futura. In this text, he claims that the fundamental problem between Catalonia and the rest of Spain is the antagonism between Barcelona and Madrid. This assertion is followed by a list of differences comparing the two cities, in which Barcelona prevails over Madrid in every case. Furthermore, Alomar belittles Madrid and its people, arguing for the supremacy of Catalan culture. For one, he accuses the people of Madrid of having a “doubly provincial” spirit, unlike the Catalans, who are cosmopolitan. He argues that unlike the people of Madrid, Catalans had the great advantage of belonging to a culturally rich historic past. According to Alomar, Castilians were conformist when it came to politics, whereas Catalans were activists. The frustrated tone in this article shows how Alomar, like so many others, fell into the same trap of comparing and contrasting these two capitals. This article would be the last one published by Alomar in Frollo’s periodical. Certainly, its negativity toward non-Catalans was unacceptable to the editor.

Besides working on bridging the gap between Barcelona and Madrid, España Futura also addressed other hot domestic topics of the day: the future of agriculture, terrorism, feminism, socialism, patriotism, nationhood, and monarchy. The periodical also reported on such international concerns as Moroccan society and politics, the cost and consequences of Spain’s colonial war in Morocco, and the crisis in Germany. Reviews of literature and art stemming from both Barcelona and Madrid served to inform both Catalans and non-Catalans, so that these two groups could better understand one another and, in the words of one journalist, so that they could live in greater harmony. In the end, the magazine failed in transmitting its message, since it did not continue after the nineteenth issue. Perhaps the Madrid readership was not interested in this Catalan-centered message of unity. Maybe its staff dissolved, or the funds to keep the periodical in print were depleted. What is certain is that the publication closed less than one year after it first appeared, and, with the arrival of the First World War, the approach to bridging the Barcelona-Madrid gap from the point of view of the Madrid cultural press would take a different turn. Renacimiento and España Futura are just two examples of little magazines centered in Madrid from the post-1898 and pre-Avant-Garde era that show a shared interest among Catalan and non-Catalan intellectuals in establishing connections between Barcelona and Madrid, as seen in their content as well as in the composition and efforts of their editorial staff. Even though España Futura was centered in Madrid, the majority of the staff were Catalans who worked toward communicating news from and about Catalonia in Spanish. As was the case with many of the little magazines, this platform for informing readers in Madrid about Catalonia was short lived, but its seeds were planted.

Before continuing to track the evolution of the relationship between the Barcelona and Madrid vanguard networks as seen in the cultural press, I would like to address briefly the reception of Italian futurism in Spain, since the movement was such a pivotal phenomenon for the development of avant-garde attitudes and manifestations in both cities. One of the first writers in Spain to report on the publication of Marinetti’s first futurist manifesto in the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro (February 20, 1909) was a defensive Gabriel Alomar in the Catalan periodical El Poble Català (Barcelona, March 9, 1909; “Spotula: El Futurisme a Paris”).18 One month after El Poble Català published Alomar’s article, Ramón Gómez de la Serna published his translation of Marinetti’s manifesto, “Fundación y manifiesto del Futurismo” (Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism), in Prometeo, the monthly magazine that his father founded.

Except for the epistolary relationship between Gómez de la Serna and Marinetti, which resulted in the “Proclama futurista a los españoles” (Futurist Proclamation to Spaniards), the news from Italy and France did not cause the same response in Madrid as in Barcelona.19 Many studies concerning the reception of futurism in Spain have suggested that after a brief outburst in 1909 and 1910, interest in futurism dissipated in Spain until the arrival of Ultraísmo ten years later. Yet I have found substantial documentation in numerous magazines from Barcelona that proves that many journalists there followed the Italian movement with sustained interest and in great detail. There was also an equally enduring interest in the other new and extravagant European vanguard style—cubism. However, since the reception of Italian futurism in Spain is not the focus of this study, I will only mention a part of the report that appeared in Barcelona in order to challenge the idea that futurism completely disappeared from the radar until 1919.

First, an article in Barcelona’s newspaper La Publicidad informed readers of a futurist disturbance in a square in Florence and announced that Barcelona’s Real Círculo Artístico planned to mount an exhibit of futurist paintings in late 1912; that exhibit subsequently fell through. Another example of the reception of Italian futurism in Barcelona can be found in Josep Junoy’s monthly journal Correo de las letras & de las artes (Barcelona, 1912). Printed entirely in Castilian, this periodical was evidently distributed and sold in Barcelona, Madrid, Florence, Berlin, London, Munich, Paris, and Buenos Aires. Although Junoy’s first attempt at directing a periodical only amounted to three issues, this very understudied journal serves as yet another example of a little magazine that attempted to offer a vast forum for international debate that also includes readers from Barcelona and Madrid. Unlike España Futura, Junoy’s periodical focused exclusively on literature and art. He announced that the magazine would be sold in five different bookstores and kiosks in Madrid. As a promoter of Italian futurism and French cubism, Correo de las letras & las artes’s first issue (November 1912) announced that Marinetti would be visiting Spain that summer to embark on a lecture tour (a visit that never took place).20 It has been documented that Junoy maintained correspondence with Marinetti, as did other members of the Catalan vanguard, including the poets Joan Salvat-Papasseit, Sebastià Sànchez-Juan, and J. V. Foix. Additionally, the Italians Gino Cantarelli and Luciano Folgore, both poets who supported futurism, also maintained epistolary contacts with another Catalan poet, Joaquim Folguera.

Another Barcelona magazine that continued to report on the developments of Italian futurism and to which Junoy contributed was Revista Nova (1914–16). Directed by the illustrator Apa (pseudonym for Feliu Elias as illustrator; his second pseudonym was Joan Sacs, when in the role of a literary and art critic), this periodical, printed entirely in Catalan, made reference to the futurist movement, in a review of the Italian periodical Lacerba, as early as its first issue (April 11, 1914, p. 10). This first mention of futurism was followed by another, in the ninth issue, by Francesc Pujols, entitled “Cubisme i Futurisme” (Cubism and Futurism) (June 6, 1914, p. 6), and in the magazine’s last issue, before it had to shut down temporarily at the onset of the Great War. Francisco Iribarne published a longer, more critical article, “Consideracions sobre el futurisme” (Concerning Futurism), written in Spanish despite its Catalan title. This piece is followed by fragments of two poems: one by Carlo Carrá and the other by Marinetti; both are reproduced from Lacerba (no. 31, November 5, 1914, pp. 4–6).

It would not be until 1916 that two other accounts of futurism appear in the Catalan cultural press. The first can be found in the little magazine Vell i nou (Barcelona, 1915–21), in an article by the Uruguayan artist and theorist Joaquin Torres-García, who had been living in Barcelona since 1891 and who contributed regularly to the cultural press.21 Another mention was by the critic and poet Rafael Sala, who traveled to Florence in 1914 and befriended members of the Lacerba group. He offered a firsthand account of futurism in the last issue of another little magazine, Themis (Vilanova i la Geltrú, 1915–16), in his article “Els futuristes i el futurisme” (Futurists and Futurism) (no. 18, March 20 1916, pp. 1–5). This article was supplemented by a Catalan translation of Marinetti’s manifesto of the futurist women, “Manifest de la dona futurista” (Manifesto to the Futurist Woman) (original dated March 25, 1912).22 Besides these fleeting mentions, the first periodical from Spain to take a committed stance on Italian futurist poetry was La Revista (Barcelona, 1915–36), directed by the literary critic and poet Josep Maria López-Picó. This magazine was printed entirely in Catalan and functions as a textbook on the formulation of contemporary Catalan culture, while also engaging in critical dialogue with the artistic activity of World War I Barcelona. La Revista is also notable for its anti-Castilian stance.23 In the case of this periodical, the editors wanted nothing to do with the centralizing forces of Madrid or its press. Unlike the other little magazines mentioned until now, La Revista was more interested in connecting with Italy and France than with the rest of Spain.

After nearly two years in print, without ever having mentioned the Italian futurist movement, La Revista published a series of Catalan translations of Italian futurist and French cubist poems, paying special attention to the experimental typography of the originals (no. 36, April 1, 1917, pp. 136–38). La Revista supplemented these poems with a brief introduction to this new style of poetry imported from Italy. These translations were an effort to remain true to a promise that the editorial staff had made to its readers one year prior to this issue: to report on the most innovative literary trends. The reception of Italian futurism in the press of Barcelona in El Poble Català, La Publicidad, Correo de las Letras & las Artes, Revista Nova, Vell i Nou, Themis (Vilanova i la Geltrú), and La Revista from 1909 to 1917 eventually led to futurist and literary cubist experiments in the more frequently referenced literary and artistic periodicals of the early Catalan vanguard years: Troços (Barcelona, 1916), Un enemic del Poble (1917), and Arc-Voltaic (1918). All three of these little magazines, centered in Barcelona, were printed before poets in Madrid renewed their interest in futurism with the founding of Ultraísmo late in the year 1918.

Troços (Barcelona, 1916–18), directed by the Catalan poet and literary critic Josep Maria Junoy, stands as the first journal in Spain and Catalonia that had as its mission the practice of avant-garde theories, namely Italian futurism, dadaism, and, above all, literary cubism. All of the contributors, aside from the illustrators, were either Catalan or French, and all of the written texts were published in Catalan. As indicated in an advertisement, the journal was sold in Barcelona, Paris, New York, and Milan, but not Madrid. Since only 101 copies of the inaugural issue were printed, the chances that this little magazine ended up in anybody’s hands in 1916 Madrid are slim, but not impossible. Although I did not find any reviews of Troços in the periodicals of Madrid, there is a possibility that one of the daily newspapers may have reviewed it. Considering that Troços was first published by the Barcelona art gallery, Galeries Laietanes, and then later by another Barcelona gallery, the Dalmau Galleries, it is likely that its readers in Barcelona would have been familiar with Francis Picabia’s equally innovative, subsequently published, Dada-inspired journal 391 (1917–24), which was founded in Barcelona. Both of these avant-garde periodicals were sold at the bookstore of the Galeries Laietanes, where the Catalan poet Joan Salvat-Papasseit worked and which many of the young poets and artists of Barcelona frequented on a regular basis, including J. V. Foix, who claimed to have visited there daily. Both Troços and 391 influenced and inspired Joan Salvat-Papasseit, who founded several avant-garde journals in Barcelona soon after these two were launched, in 1916 and 1917, respectively.

Stage 2: Revolution (1909–23)

Prior to the creation of Troços and 391, two other important cultural periodicals, one from Madrid and the other from Barcelona, both established in 1915, explicitly had as one of their central missions the creation of a greater dialogue between the two cities they represented: España (Madrid, 1915–24) and Iberia (Barcelona, 1915–19). Originally directed by the philosopher José Ortega y Gasset, España outlasted the Great War, even though it encountered great challenges on several occasions.24 This periodical covered an array of topics including art, poetry, theater, music, and book reviews in approximately twelve pages per issue. The magazine’s main political concerns included Spain’s colonial war in Morocco and the “Catalan problem.” As stated on the cover of the first issue, its goal was to renew the lost faith in Spain, as felt by the editorial staff. After the Disaster of 1898 and all of the political, social, and economic turmoil that characterized the first two decades of twentieth-century Spain, the staff at España—and presumably its readership—had lost hope in the country’s state-run institutions, especially the government.

España’s mission was to renew the lost faith of Spaniards with optimism, while its editorial team worked toward uniting a fragmented nation. Their goal was “ante todo, una solidaridad” (before all else, solidarity). In order to achieve this ambitious goal, the staff members were carefully selected to represent a wide range of Spanish regions. Even though this periodical was published in Madrid, the editors aspired to create a publication that would be written by the entire nation, because for them, Madrid did not represent the “moral center” of Spain.25 Following this mission statement, there is a long list of contributors, representing twenty different cities or regions of Spain. These locations were printed in capital letters, followed by the corresponding names of España’s journalists in title-case letters. Even though only three Catalans were listed as the magazine’s representatives in Barcelona (Pedro Corominas, Manuel Reventós, and A. Ras), over the magazine’s lifespan, reaching over four hundred issues, many other Catalans would be added to this list, including Salvador Albert, Gabriel Alomar, Salvador Dalí, Marcelino Domingo, Eugeni d’Ors, and J. J. Pérez-Domènech.

One critical contributor to the periodical who is not mentioned in this original list is the Catalan artist behind most of the cover pages of España, Luís Bagaría (Barcelona, 1882–Havana, 1940). As one of the most popular caricaturists among the intellectual elite of Madrid, his cartoons appeared in the newspaper El Sol nearly every day. Bagaría was born in Barcelona and spent most of his youth and adolescence there until his father’s death in 1899, after which he accompanied his mother to Mexico, Cuba, and New York. One of the crucial discoveries he made while in Latin America was an interest in the visual arts. He and his mother returned to Barcelona, where he was taken under the wing of the noucentista painter Santiago Rusiñol, who was also a poet and playwright. By 1905, at the age of 25, Bagaría was showing his work in Paris. After a brief return to Cuba in 1908, he made Madrid his permanent home until the Spanish Civil War, when he moved to Paris (1938) before exiling to Cuba. While in Madrid, he was one of the founders of the Pombo tertulia alongside Ramón Gómez de la Serna. Bagaría’s connections to the vanguard networks in Barcelona and Madrid through his work as an illustrator and journalist make him one of the central nodes of the Avant-Garde network in Spain, even though most have probably never heard of him.

In the spirit of solidarity, the number of articles in España that addressed some aspect of Catalan culture or politics, either briefly or in detail, is remarkable. Gabriel Alomar or Marcelino Domingo wrote most of these articles, and they were always printed in Spanish.26 Evidently, Alomar found a new forum in Madrid after España Futura folded. Over the course of its history, this Madrid-based journal also published articles about Catalonia, Catalans, and Catalan culture written by non-Catalans, two exceptional examples being “El caso de Dalí” (The Case of Dalí), by the pioneering Spanish playwright Cipriano Rivas Cherif, and a review of Antoni Rovira i Virgili’s book, El nacionalismo catalán (Catalan Nationalism), written by Nuñez de Cuevas. Much like another periodical from Madrid, La Esfera, España dedicated an entire issue to Catalonia and Catalan culture (June 1916). This special issue leads with the headline: “¿Qué es el catalanismo?” (What is Catalanism?). The author of the anonymously written article on the front page states that any liberal Spaniard interested in decentralizing the state and fostering regionalism should be interested in Catalanism. The fact that an entire issue was devoted to Catalan nationalism suggests that the editorial staff of España shared these views and hoped to convince their readership of the same. The following issue, one week later, published a series of reactions to this Catalan-centered feature issue. Catalans and non-Catalans quickly responded and sent letters to the editorial staff for publication. This speedy reply shows that Catalan culture and politics were controversial, as well as a subject of high interest for both the readership and the editorial staff.

Specifically, the Catalanism issue included articles by the politician Francesc Cambó (a fragment from a speech he gave to Madrid’s Parliament); a definition of “nation” by another politician, president of the Mancomunitat Enric Prat de la Riba; a definition of “nationalism” by the author of Historia dels moviments nacionalistes, La nacionalització de Catalunya, and Debats sobre el catalanisme (The History of Nationalist Movements, The Nationalization of Catalonia, and Debates about Catalanism), Antoni Rovira i Virgili; a definition by the poet Josep Carner of “El hecho catalán” (The Catalan Fact); an anonymously written list of the demands of Catalan nationalism that included the desire for an autonomous state, as well as executive, legislative, and judicial power, in addition to freedom of speech in Catalan for all private and public events; and finally, an article about Catalonia’s economy. In conjunction with these political and economic issues, art, language, and literature were also included in the definition of Catalanism. The issue ends with an article by the politician Marcelino Domingo, “¿Qué es España y qué es Cataluña?” (What is Spain and What is Catalonia?), which is a fragment of a speech he gave in Congress a few days prior to this issue’s publication. In the midst of war, readers of España in Madrid had the opportunity to learn about Barcelona, Catalonia, and Catalan culture in Spanish and from the point of view of both Catalan and non-Catalan journalists.

The group of intellectuals that orbited around this weekly periodical created in Madrid came to be associated with the so-called Generation of 1914. This term, which was coined much later, places importance on 1914 as the year of the beginning of the Great War. This group of writers consisted of intellectuals like José Ortega y Gasset (editor of España in 1915), Luis Araquistain (editor of España from 1916–22), Manuel Azaña (editor of España from 1923–24), Ramón Gómez de la Serna, Gregorio Marañón, Gabriel Miró, Ramón Pérez de Ayala, and many others, including several women. Two Catalan writers who are sometimes associated with this group are Eugeni d’Ors (noucentisme leader) and Gabriel Alomar (futurisme founder). The phrase “Generation of 1914” is sometimes used interchangeably with the term “novecentistas,” in a direct reference to the Catalan noucentistas. Similar to the goals of noucentisme, these writers focused on defining Spain’s identity as a nation after the Disaster of 1898 by initiating radical and systematic changes in their vision of Spain and its role in history. “Science” was a key word for the Generation of 1914 writers, who openly promoted the “Europeanization” of Spain. The contents of España also imply that the Spain of the future was one that would be politically decentralized and strengthened by having its many regions work together.

The Barcelona counterpart of Madrid’s weekly periodical España was Iberia. These two journals shared many characteristics. Both were weekly periodicals, were printed primarily in Spanish, and consisted of articles that expressed an overall preoccupation with the state of Spain as a whole from a cultural perspective. Unlike the Madrid-based journal, the Barcelona magazine preferred the more encompassing term of Iberia, which includes Portugal. Correspondingly, Iberia published articles in multiple languages, including Spanish, Catalan, and Portuguese. One of the most striking similarities between these two periodicals is the layout of their cover pages. Both consisted of a one-word title in the masthead, followed by a large illustration, almost always printed in color, with a few lines of commentary text underneath the image. The main illustrator for the Madrid magazine was the Catalan Lluís Bagaría, although other, non-Catalan artists were also featured. The most frequent illustrator for the Barcelona periodical was the Catalan artist Apa, but it also featured works by other Catalan artists, notably Inglada, Colom, Canals, and Aragay.

One of the main political differences between the two periodicals is that the editors of España insisted that their stance was neutral in relation to the Great War, while Iberia explicitly allied itself with France and Britain. According to the editor of the facsimile edition of España, the periodical received funding from private British entities on several occasions in order to stay afloat. Unlike España, which survived until 1924 and published over four hundred issues, Iberia only lasted until 1919, with half that number of issues. Another major difference between the two periodicals is that the journalists who wrote for Iberia did not represent as many different places in Spain as those who wrote for España. Very few Madrid-based reporters contributed to Iberia, whereas at least a handful of Catalans regularly contributed to España, such as the caricaturist Luis Bagaría.

Curiously enough, the editor in chief of Iberia, Claudi Ametlla, who had been a contributor to the Catalan subversive periodical El Poble Català (1906), opened the first issue with a mission statement by a non-Catalan, Miguel de Unamuno. The statement is written in Spanish, like the majority of articles in Iberia. In this inaugural message, Unamuno explains that this periodical was the result of an idea for a multilingual magazine that he and his “soul mate,” the Catalan poet Joan Maragall, had envisioned many years earlier. The magazine they envisioned was also to have been called “Iberia,” and it would have included the “literary languages” of the Iberian Peninsula, especially Spanish, Catalan, and Portuguese. In this opening statement for the inaugural issue, Unamuno states that he and Maragall discussed this project through a series of letters, some of which have been collected and are readily available. One of Maragall’s propositions in this correspondence was that the periodical base itself in the city of Salamanca, both because of its proximity to Portugal and because it represented more of a neutral space in comparison to Barcelona or Madrid. For Maragall, Salamanca was an alternative cultural, intellectual, and spiritual center of Spain. Instead, this project, which finally came to fruition in 1915, was based out of Barcelona.

Similar to Ortega y Gasset’s inaugural message in España, Unamuno stated that if people from the different regions of Spain, with their diverse languages, history, literature, and cultures, were going to understand one another better, they first had to learn about one another. Furthermore, Unamuno, much as Alomar had argued in España, emphasized the importance of the “spiritual proximity” between the different peoples of Spain:

Halagábame el llegar a tener un órgano de aproximación espiritual entre los pueblos ibéricos de distintas lenguas. Aproximarse espiritualmente es conocerse cada vez mejor. Y mi ensueño y anhelo ha sido que nos conozcamos mejor, aunque sea para disentir.

(It flattered me to one day have an instrument of spiritual approximation between the different peoples of Iberia and their different languages. To come closer spiritually is to get to know one another even more. And my dream and desire has been that we get to know one another better, even if it means to disagree.)27

Unamuno had been dreaming of a platform from which the different cultures and languages of the Iberian Peninsula could come together. In this process of achieving some sort of mutual understanding, it was Unamuno’s vision that all of the different regions of Spain and Portugal would discover a broader Iberian spirit or identity. As he goes on to explain, that spirit would be that which differentiates Iberians from other Europeans. He emphasized that Iberians must defend that which differentiates them, just as much as that which unites them. Unamuno believed that without these differences, life was simply not worth living. Given the scenario of the World War, Unamuno feared that Europe would fall under an oppressive dictatorship in which Germany would dominate every other European country. Spaniards would become the “worker bees” of the Germans, and in the process they would lose their identity. Unamuno also predicted that this war would evoke repressed feelings of national identity. He finally urged the people of Iberia to resist the violent imposition of one language over another as in Alsace-Lorraine and Poland, because “La unidad es buena y santa, pero cuando es violentada no es unidad” (Unity is good and sacred, but when it is violent, it is not real).

Two years after the publication of the first issues of Iberia and España, Spain was in turmoil. The Russian Revolution erupted in February and the Great War continued. The social, political, and economic consequences of Spain’s neutrality in the war led to a general strike in August 1917. The unrest in Barcelona, plus the influx of European avant-garde artists escaping the First World War, was the ideal breeding ground for a new kind of periodical. The Catalan poet Joan Salvat-Papasseit founded Un enemic del Poble (An Enemy of the People) (Barcelona, 1917–19), which, like its predecessors Iberia and España, included Catalan and non-Catalan writers in its eighteen issues. It was published on an irregular schedule, even though it was intended to be monthly. The mission statement emphatically denied association with any group or aesthetic movement, or as the painter Joaquín Torres-García put it, “Tindríem d’ésser inclassificables” (We must be unclassifiable). But the editor published several literary and artistic manifestos that defined the publication’s radical ideas. In order to illustrate these points, the editor published poems that put into practice typographic experiments reminiscent of Italian futurism, Swiss dadaism, and French literary cubism. Un enemic del Poble is a small-circulation periodical directly related to the nascent literary avant-garde movement in Catalonia, in direct line with Troços and 391. In form and content, it was the antithesis of España and Iberia. The journal itself was very small. Each issue consisted of one large folio printed on both sides.

Unlike the periodicals that worked toward unifying the spirit of Spain, like Iberia and España, as Unamuno put it, Salvat-Papasseit explicitly wrote in his mission statement that his goal was not to create any sort of collective spirit: “Un enemic del Poble no correspond per ara, a cap necessitat d’ànima collectiva. N’estem tan convençuts que [sic] sols el publiquem per satisfacció pròpia” (Un enemic del Poble, for the moment, does not answer to any necessity for a collective spirit. We are so positive in that respect that we are only publishing out of personal satisfaction).28 In saying so, Salvat-Papasseit speaks directly against the philosophy of more mainstream journals like Iberia and España. Later on, the Uruguayan painter and theorist Joaquin Torres-García would further define the little magazine’s role, in Catalan, as consisting of “individualismo, presentisme, internacionalisme” (individualism, being present, internationalism).29 Even though there are more Catalan than Castilian texts overall in the lifespan of the avant-garde periodical, almost every other issue includes a Spanish text. Sometimes contributions in Spanish appeared on the front page, as was the case with a text written by the Madrid Avant-Garde enthusiast Ramón Gómez de la Serna.

The inclusion of Spanish in Un enemic del Poble made Salvat-Papasseit’s “subversive paper” accessible to more readers. Even if it did not end up in anyone’s hands outside of Catalonia, it sent out a message to non-Catalans in Spain that they too were welcome to participate in this cause. It also sent a political message that it was interested in including Spanish-speakers, not just Catalan-speakers, in its efforts to be individualistic, present and international. Un enemic del Poble acted out its inclusionary politics without having to explain them in any sort of mission statement, as many of the other periodicals discussed so far did. In the case of this little magazine, there was no space to waste. There were only two pages available for each issue. Salvat-Papasseit began a literary and aesthetic movement in Barcelona through this periodical that welcomed anyone who shared his mission and was willing to collaborate, whether they spoke in Catalan, Castilian, Italian, or French—all the languages that appeared in print without translation. By openly including non-Catalans, Salvat-Papasseit spun a web of contacts for himself in Madrid. Along these same lines, his second publishing enterprise, Arc-Voltaic (Barcelona, 1918), expanded on this notion of all-inclusiveness toward other languages. Once again, texts were published in their original languages: Catalan, Italian, French, and Spanish. Unfortunately, there was only one issue of this periodical, with an illustration by the avant-garde painter Joan Miró on the cover, before it folded. It was likely because of these early contacts with Castilian writers like Ramón Gómez de la Serna in Madrid, as well as his openness toward other languages and cultures, that Salvat-Papasseit was one of the only Catalan poets published in the little magazines associated with Madrid’s vanguard Ultraísmo movement.30

Ultraísmo, also referred to as Ultra, materialized toward the end of 1918 and was practiced by a group of young poets living in Madrid desperately seeking to renovate poetic language. The first Ultra manifesto was published in Madrid in January 1919. Even though it is primarily considered a poetic movement, it also made room for visual texts. Some of the most active participants of Ultra were three foreign artists in residence in Madrid: the Uruguayan Rafael Barradas, the Argentinean Norah Borges, and the Polish Wladyslaw Jahl. Generally speaking, Ultraísmo was a combination of the isms that preceded it, including futurism, dadaism, creacionismo, cubism, expressionism, vibrationism, and others. First and foremost, and in the spirit of other vanguard movements, it was created to radically oppose the modernismo style of poetry practiced by Latin American and Spanish poets since the late nineteenth century. Like many of the other European avant-garde movements, Ultraísmo spread its message through the platform of the little magazines and by organizing social events like literary clubs, banquets, and poetry recitals. Curiously, despite the diversity of Ultraísmo’s team of players in Madrid, who represented almost every Spanish region, the only Catalan participants were Salvat-Papasseit (poet), Sebastià Gasch (art critic), and Salvador Dalí (painter). In his latest study of the little magazines related to the Spanish Avant-Garde, Rafael Osuna makes note of the absence of Catalans in Madrid’s Ultraísmo movement:

Ante tanto nombre español y francés, un nombre catalán salta a la vista en la salida sexta (de la revista Grecia). Se trata de la reseña que se le hace a Les absències paternals de José María López-Picó; lo mismo se podría haber reseñado un libro húngaro, pues los catalanes, tanto novecentistas como actuales, brillan por su ausencia aquí como casi en el resto de la hemerografía española vanguardista de la época, ignorándose ambas culturas mutuamente.

(Among so many Spanish and French names, a Catalan name sticks out in the sixth issue [of the little magazine Grecia]. It is a review of a book by José María López-Picó titled Les absències paternals [Paternal Absences]; it might as well have been a review of a Hungarian book, since the Catalans, noucentistas and vanguardist, shine for their absence here just as they do in the whole Spanish Avant-Garde hemerography of the era, both cultures mutually ignoring one another.)31

Osuna’s claim that Catalans were completely absent from the hemerography of Spain’s Avant-Garde is not entirely accurate. Perhaps their periodicals were not included in the hemerographic archives in Madrid, something I found to be the case; but that does not mean that they did not exist. One must consult the Catalan magazines in the Barcelona archives in order to see that Osuna was only focusing on Madrid.32 Just because Catalans did not participate in Madrid’s Ultraísmo movement does not mean that they were not involved with the Avant-Garde movement. In fact, artists and poets in Barcelona were the first to experiment with European avant-garde ideas, as seen in periodicals that predate the Ultra movement, already discussed, such as Troços (1916), 391 (1917), Un enemic del Poble (1917), and Arc-Voltaic (1918).

Osuna oversimplifies when he claims that the Catalans and Spaniards mutually ignored one another throughout the vanguard years in Spain. The people of Barcelona and Madrid who were involved in the founding, practice, and promotion of these experimental movements—poets, painters, sculptors, illustrators, journalists, editors—were well aware of the literary and artistic news from the other city, primarily through the contents of the little magazines (e.g., book and magazine reviews), as well as through friendships and cultural events like art shows. One example can be found in a review of little magazines penned by Héctor (pseudonym for Guillermo de Torre) in the periodical Cervantes (Madrid, 1916–20). In this review, he demonstrates his knowledge of little magazines in Barcelona:

Sus últimos números dejan ya insinuar el florecimiento de las nuevas direcciones ultraístas que al ser paralelizadas en las mismas páginas, con rescoldos líricos estrictamente novecentistas, adquieren un confrontamiento de superación, Grecia es, con algunas revistas barcelonesas, la publicación española más juvenil y sugeridora del momento.

(Their latest issues are more forthright about the new direction of poetry as proposed by Ultra, that by being situated next to and on the same pages with embers of strictly nineteenth-century lyricism, they acquire a confrontation that supersedes this old style of poetry, Grecia is, along with some magazines from Barcelona, the most youthful and suggestive Spanish periodical of the moment.)33

Guillermo de Torre, for one, was aware of the little magazines published in Barcelona; why would his closest friends and colleagues be unaware? The majority of the literary periodicals of this time period had a section either at the beginning or at the end of the issue that reviewed other magazines and newly published books. The function of such sections was for the readers to stay on top of new publications, but also to stay connected to the newest literary and aesthetic trends outside of Madrid. Barcelona magazines were not often reviewed in Madrid’s periodicals and vice versa, but it was one of the ways that the Avant-Garde practitioners from either city could be more aware of one another, as in this particular case from the periodical Cervantes.

Osuna is right in saying that the collaboration (or inclusion) of Catalans within the pages of Madrid’s Ultra magazines was almost nonexistent. One of the reasons why it may appear that the Catalan periodicals had no role in the Spanish Avant-Garde is because the Madrid press, for the most part, did not pay close attention to it, or perhaps they chose to ignore the Catalan movement. Beginning when Guillermo de Torre published Literaturas europeas de vanguardia (1925), and continuing until today, as in the case of Osuna’s Revistas españolas de vanguardia (2005), the periodicals from Catalonia are almost always left out of the picture in telling the story of the Avant-Garde movement in Spain as a whole. One Catalan magazine that has made its way over the divide into the histories of both sides of the Avant-Garde story in Spain is L’Amic de les Arts (The Friend of the Arts) (Sitges, 1926–29), but it was certainly not the only Catalan periodical that promoted avant-garde ideas and practices throughout this period.

One question that begs an answer is why the names of Catalans do not appear in the little magazines from Madrid but do appear in avant-garde periodicals from smaller cities in Spain and abroad, such as Alfar (A Coruña, 1920–54), Ronsel (Lugo, 1924), Mediodía (Sevilla, 1926–29), and Circunvalación (Mexico, 1928). Were the Catalans purposefully excluded from the Ultra magazines in Madrid? Were the Catalans not interested in Ultra? In a modification of his definition of Ultra, Osuna states that in fact it was not a movement that was a “mixed bag” of everything: “Todo no, en realidad, pues los catalanes ni están en España ni en Francia ni en Europa: simplemente no se les presta atención” (Not really everything, because the Catalans were not in Spain or France or Europe: they are simply ignored).34 If the Catalans were neither in Spain, France, nor Europe, does Osuna suggest that they were only in Catalonia? And who is ignoring the Catalans—the artists, writers, and editors of magazines in Madrid, the scholars of today, or both? Were the Catalans not concerned about publishing their poetry in Madrid? Was their intention to publish only in Barcelona or Catalonia, and only in Catalan? Joan Salvat-Papasseit published several of his poems in Madrid and founded two multilingual periodicals; therefore it would be erroneous to say that the avant-garde movement in Barcelona was completely insular. It would be more accurate to say that from the introduction of Italian futurism in 1909 until the beginning of the Miguel Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship in 1923, the vanguard movements in Barcelona and Madrid were out of synch, but not out of touch.

Stage 3: Retreat (1923–29)

By the time the Ultraísmo movement played itself out in Madrid (1923) and before surrealism picked up any steam (1929), the cultural periodicals in Spain passed through a third stage. Generally speaking, the main trend during this period was that even fewer Catalans contributed to the Madrid press and vice versa. During this post-Ultraísmo phase, only a few vanguard journals can be found on Madrid’s cultural press radar, including Vértices (1923), Tobogán (1924), Plural (1925), and Atlántico (1929–30)—all of which were short-lived periodicals. Tobogán was the least avant-garde of these, while the others still show some signs of experimentation. The only Catalan names that appear in any of these little magazines were those of two critics: the Valencian ex-Ultraísta J. J. Pérez Domènech and the Catalan art critic Sebastià Gasch. Similarly, almost no names or mentions of Spanish poets, artists, or critics from outside of Catalonia appear printed in the pages of the vanguard periodicals of Barcelona. Instead, a group of pro-Catalan magazines formed a sort of barricade from the rest of Spain. All of the journals that were established in Barcelona during the Primo de Rivera dictatorship took a unified stance to protect the Catalan language and culture from further aggression.35 The only non-Catalan Spaniards who contributed to any of these cultural periodicals appeared in the last issue of L’Amic de les Arts that was entirely masterminded by Salvador Dalí (March 1929). Dalí’s friends from Madrid that contributed to this issue of L’Amic included Pepín Bello (Andalusian), Luis Buñuel (Aragonese), and Federico García Lorca (Andalusian). All of these men were Salvador Dalí’s friends from his time at the Residencia de Estudiantes in Madrid.

Any progress that may have been made in increasing communication and awareness between the people of Barcelona and Madrid through the cultural press in the previous decade was almost completely erased during the Primo de Rivera dictatorship. During this time, both cities turned inwards, and this introspection reveals itself in the content of the magazines. Two exceptions to this rule include a periodical from Madrid, La Gaceta Literaria (1927–31), which is discussed at length in the final chapter of this book, and Les Arts Catalanes (1928–29) from Barcelona. In the case of the former, one of the periodical’s main missions was, once again, to create a greater dialogue between Madrid and the rest of Spain, especially Catalonia, Portugal, and Latin America. The editor frequently printed articles in Catalan, and the magazine included several Catalans on its regular staff. In the case of the latter, Les Arts Catalanes, this periodical printed the lead article of every issue in four languages: Catalan, French, Castilian, and English. The journal’s mission statement, which appeared in the inaugural issue (October 1928), was published in these four languages. This free, monthly magazine consisted of art, journal reviews, art exhibit reviews, and schedules of exhibits in Catalonia and also outside of Spain. This little magazine dedicated to the contemporary arts was clearly interested in taking an international stance. Since the journal only published eight issues, its impact may have been minor, but nevertheless, a seed was planted.

Outside of Madrid and Barcelona, the names of writers and artists from both cities often appeared side by side in the small-circulation periodicals located in the peripheries of Spain and Latin America. Up until this date, the only Catalans who contributed to any of these peripheral periodicals were either critics or visual artists, such as Salvador Dalí and Sebastià Gasch, not poets. By 1926 the names of several Catalans began to surface in these little magazines outside of Barcelona and Madrid. For example, Mediodía (Sevilla, 1926–29) published the work of Dalí and Gasch but also that of three other Catalan writers: Tomàs Garcés, Lluís Montanyà, and Eugeni d’Ors.36 Another little magazine from the south of Spain that published works by Catalan artists like Dalí, Josep de Togores, and Apel·les Fenosa was Litoral (Málaga, 1926–29). Another journal from the south of Spain, Verso y Prosa (Murcia, 1927–28), which was also sold in Madrid, also published texts by Dalí and Gasch. Another Catalan, Eugeni d’Ors, and again Gasch, published in another little magazine from Andalusia, Papel de Aleluyas (Huelva/Sevilla, 1927–28). Finally, one last example of the appearance of Catalans in the little magazines from the south of Spain is Meridiano (Huelva, 1929–30), which published works by Dalí and Gasch.

A similar pattern can be seen in three avant-garde periodicals from Latin America: Amauta (Lima, 1926–32), Sagitario (Mexico, 1926–27), and Circunvalación (Mexico, 1928). Since the Latin American avant-garde magazines are not the focus of this study, I did not delve deeper into this area of the investigation, but at least in these three cases, Dalí and Gasch were included, as were Joan Miró, Eugeni d’Ors, and the literary critic Josep Maria de Sucre. The periodical Circunvalación is particularly interesting for the purposes of this study. First, it included the greatest number of Catalan contributors of any of this group of Latin American avant-garde periodicals, although only three issues made it to print. Notably, its mission statement, printed perpendicular to the rest of the words on the page and outlined in red, stated: “Para el diálogo y para la amistad” (In the name of dialogue and friendship). The editors of this vanguard magazine draw attention to the fact that expansive networking, effective communication, and strong friendships were critical elements of the Avant-Garde. The particular goal of this free periodical, Circunvalación, was to embrace all. It was created to connect people with similar interests despite their differences (e.g., geographical, national, linguistic). The binding force that united them was a shared belief in the Avant-Garde spirit, or renewal, renovation, and change.

One explanation for the participation of the Catalans in these peripheral periodicals, outside of Madrid and Barcelona, is that there simply were not many vanguard magazines published in either of these cities during the Primo de Rivera dictatorship.37 Another possibility is that since one of the main goals of these little magazines was to connect with the larger world outside of their small circles, they extended their network to include experimental poets and artists from other Spanish cities. Many of these contacts were initiated by friends, or by connecting with friends of friends. For instance, Salvador Dalí’s frequent appearance in the periodicals of Andalusia can be explained by his close friendship with Federico García Lorca. In 1928, Lorca founded his own little magazine, Gallo, in his hometown of Granada, with the help of two Catalan friends: one from Madrid, Dalí, and the other from Barcelona, Gasch.

From the marketing point of view, publishing notable writers and artists added value to these little magazines on the periphery. For instance, if one of the most respected art critics of Barcelona and Madrid contributed to the journal, it would make the publication more attractive. It was also another way of expanding the entire network. By publishing in Murcia (Verso y Prosa) or Huelva (Papel de Aleluyas, Meridiano), the overall Avant-Garde network expanded. Interestingly, periodicals on the periphery of Barcelona, but still within Catalonia, also show an interest in publishing the work of non-Catalans from Spain. First, Ciutat (Manresa, 1926–28) not only published the work of Federico García Lorca, but also featured an article about him in Catalan written by Josep Maria de Sucre. The avant-garde magazine Hèlix (Vilafranca del Penedès, 1929–30) published the greatest number of texts from non-Catalan Spaniards representative of the avant-garde style, including Gerardo Diego, Ernesto Giménez Caballero, Ramón Gómez de la Serna, Benjamín Jarnés, and Ledesma Ramos. All of their works were published in Spanish. Finally, there is the case of L’Amic de les Arts out of Sitges, mentioned earlier.