Our choices about motherhood have expanded enormously over the past sixty years. In generations past, the lack of effective birth control, along with rigid societal expectations, meant that almost all women who were fertile had children. Today, however, access to birth control, legal abortion, reproductive technologies, and adoption make it possible for more of us to control whether, with whom, and when to have children. In addition, changing laws and social mores have led to greater acceptance of women who decide not to have children, as well as of single women, same-sex couples, and other nontraditional families who seek to conceive or adopt a child.

For some women, the urge to have a baby is strong and clear:

Sometime when I was eighteen, some specific biological thing started to tick inside me—I think I actually have a memory of feeling it start, or at least of suddenly becoming aware of it. Out of nowhere came this deep hunger to be pregnant, to have a tiny living creature inside me, to experience my body going through the processes of pregnancy and childbirth. I think about being pregnant all the time, and my belly and my chest actually ache when I see pregnant people or small babies.

Others are equally certain that children are not in the future:

I am not interested in having children at all. . . . Fortunately [I am] with someone who also doesn’t want to have children. We talk about the social pressures put upon us and the judgments we encounter, and how relaxing it is to be in a relationship with someone who shares the position of not wanting to have children.

And many of us find ourselves, at some point (or points), struggling with ambivalence:

I still debate whether or not I want to have children. Some of the reasons relate to whether or not I really want to dedicate that much of my life to children at the sacrifice of personal pursuits versus whether or not I think I will regret it or feel lonely one day for not making that choice.

Life’s realities often interfere with our desires. You may be single and not want to raise a child alone or in love with someone who doesn’t want to be a parent. Limited financial or other resources may make it difficult to imagine having and raising a child. You may find yourself pregnant without having consciously made a decision to do so, or you may be infertile or have an illness or disability that prevents conception, pregnancy, or parenthood. Having more control of our fertility can give us the ability and time to think deeply and fully about becoming mothers, but sometimes, for all the consideration we give it, what occurs is the opposite of what we intended.

Children can bring joy and complexity into our lives in ways we might not even imagine. As they grow and change, we grow and change along with them. It can be wonderful sharing activities, stories, and places with our children that meant something to us when we were young. Children can challenge and inspire us to make the world a better place, and they give us a way to be part of the continuity of life. Many of us want to nurture and love children of our own and consider having a baby to be one of the richest human experiences.

I loved being pregnant, and our partnership while I was pregnant and when our girls were new babies was amazing: our emotional and sexual intimacy was intense. The feelings of joy and love and hope that I’ve experienced as a parent are like nothing I could have imagined.

At the same time, being a parent involves exchanging spontaneity and relative control of everyday life for a huge responsibility, complicated schedules, and relative chaos. Juggling your needs and dreams alongside the needs and demands of your child is an ongoing challenge. You may fear bringing children into a troubled world or want to pursue dreams incompatible with child rearing. Being child-free often means more personal freedom and more time, money, and energy to invest in relationships, work, and other interests and passions.

Not having a child has given me time to pursue my love of singing and theater. It allows me to focus on myself, which is important to me because I’m in a helping profession. I can’t quite imagine seeing clients all day and then going home and taking care of kids all night. I do sometimes feel like I’m missing out on something really important, but most of the time I’m happy with my choice. I like having children in my life but not being responsible for them.

Like many of the choices we make, the decision whether to have children is influenced by our families, our communities, our culture, and the society in which we live. It can be difficult to separate our genuine feelings about being a mother from the external pressure most of us feel to have a child:

I debate this question under the shadow of the mainstream media that try to scare women into thinking marriage/children is the most important thing in life. . . . People, especially women, who remain single are seen as failures regardless of how successful and fulfilling the rest of their lives may be.

As we think about whether to parent, many questions arise. Some have straightforward answers. Others are more complicated: Does my job give me financial stability? Do I have a stable household? Is my partner or any other household member abusive in any way? What about alcohol and drugs? Are there family medical problems that might be passed on genetically? Do I have parenting skills, or am I eager to learn them? How will I juggle work and child care? If I am single, how would having a child affect any new intimate relationships? Do I have adequate health care insurance and accessible health care? What will the financial costs be? What kinds of values would I want to encourage in my child, and who could help me do this? What kind of community would I want to raise children in? Would I have support if I or my child develop a disability? Am I ready to prepare a child to deal with difficulties in life, such as racism, sexism, and homophobia? Am I too young? Do I know what I’m doing? Am I too old? What if something happens to me and someone else has to raise my child?

And that’s just the start. If you have a partner, talk about the kind and amount of involvement in child rearing you each would want to have. Would one of you stay home with the baby? Would you find child care? If your partner is a man, you may want to be especially conscientious about discussing how he, too, and not just you, will be balancing parenting, work, and other priorities.

Try, too, to evaluate your emotional resources for parenting. Are there caring people around you to help you keep your perspective, your temper, your sense of humor, and your sanity in the midst of the emotional upheaval, changes, and chaos that occur with parenthood? Is there a mother or mother figures you can turn to for advice, support, and resources?

Answering “no” to any of these questions does not mean you should not have children. They are just considerations. Many of us feel that it’s impossible ever to feel completely ready to be a parent:

My husband and I batted the idea of children around for a while. There are enough reasons to have them as there are to not have them. Every other milestone in our relationship seemed to take a while, but when we decided to have a child, we just closed our eyes and jumped. If we’d have deliberated on children as long as we did our other decisions, we’d never have a kid!

Three women reflect on how they made the decision to have children and how they felt in the aftermath of their decisions:

I spent a lot of time being the oldest child and helping my mother out with my siblings. I don’t remember being a happy child or ever wanting or thinking I would have children. Then I became a social worker and youth worker. One day I realized I spend all my time caring for children, exactly what I thought I didn’t want! After getting over my fears, I finally had a child, and it is the best thing that ever happened in my very wonderful life. She is a complete joy, and I feel so lucky. My biggest regret is getting started too late and only having one child.

I love kids, but I’ve never had a strong urge to have them myself. I always wondered: How do you fit together the pieces of taking care of yourself and being a parent? I was single for most of my thirties, then got involved with someone who was sure he didn’t want children. But I still felt it was important for me to make an active choice for myself—I didn’t want to say no just because he said no. I talked with a lot of women, looked at both sides, then decided against having a child. The hardest part was telling my parents, because I felt like they’d be so disappointed in me. But when I did, I felt a tremendous relief, and really, I haven’t thought about it much since.

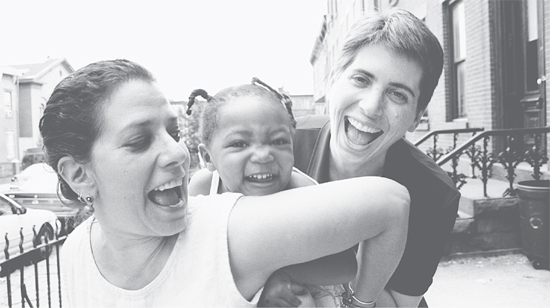

© Donna Alberico

I had a child at forty-six. Before that, although I loved being with other people’s children, anytime something went wrong and the child irritated me, I would think to myself, How could I ever stand the full-time responsibility of being a mother? Somehow, becoming a mother changed that. There is an intangible, indescribable bond intrinsic to the relationship that in the long run transcends the petty everyday irritating occurrences.

Once my husband and I had been married a few years, there were constant questions about when we would start a family—particularly from our parents, whose friends were all grandparents. Then there was additional pressure when our friends were all having children—this changed the dynamics of our friendships and was an unexpected result of deciding not to have children.

The societal and familial pressures on women to have children can be intense. Our culture sees having children as an intrinsic part of being a woman, and many people assume that a woman cannot be truly fulfilled if she doesn’t have a child. Those of us who choose not to have children are often judged as selfish by those around us. Many of us find it helpful to join a support group or find others ways to connect with people who support and validate our choice. For more information and support, see the Childless by Choice Project at childlessby choiceproject.com.

In becoming parents, we embark on a transformative journey. Welcoming children into our lives brings moments of elation, fear, grief, frustration, and joy. This section offers a brief overview of several different paths to parenthood: conceiving and bearing a child; adopting; or caring for a foster child.

It’s amazing how little we are taught about our own bodies in health class. We get a few basic lessons on birth control, but that’s it. Where is the detailed information on predicting the timing of ovulation and learning to monitor your own unique fertility patterns? It certainly wasn’t covered in my high school health curriculum.

Once you decide to try to get pregnant, you may be surprised to find that you know much more about preventing pregnancy than about achieving it. Charting your menstrual cycle is one way to learn about fertility “signals” and optimize your chance of getting pregnant. (To find out more, see “Charting Your Menstrual Cycles.”)

If possible, it’s good to meet with your health care provider or a maternity care provider before you begin trying to get pregnant. A preconception visit can help you learn about how to best prepare for pregnancy. During this visit, a good health care provider will do the following:

• Learn about your past pregnancies and births, take a family history, and examine you to assess for potential problems during pregnancy.

• Identify ways to help you manage current medical conditions and avoid pregnancy complications.

• Review all medications you are taking and recommend changes, if necessary.

• Learn whether you are a good candidate for genetic screening tests.

• Offer any immunizations you need that cannot be given during pregnancy.

• Recommend that you start taking folic acid supplements (400 mcg a day for most women) a few months before you start trying to conceive.

• Offer support and help for substance abuse, such as smoking cessation and/or alcohol or drug abuse.

• Identify any unsafe environmental exposures you can reduce or eliminate during pregnancy.

Adoption is another way to create or extend families. You may be unable to conceive, or you may have a medical condition that would make pregnancy and childbirth unsafe. Some women prefer not to become pregnant or choose adoption over giving birth out of concern for children who need loving families.

Adopting Katy has been the greatest joy of my life. She is 11 months old now and was born in Kazakhstan. Several people have said how lucky Katy is or how brave I am to be doing this alone. In all honesty, though, I am the lucky one to have such a fabulous daughter, and courage has nothing to do with it. A mother’s love and desire are what made (and continues to make) this family happen. I have never been more sure of anything and am thrilled that she is my daughter.

Another woman says of her experience adopting after infertility:

The time between finding out you cannot or should not have a pregnancy and deciding to follow a new dream is the saddest time. In life there are no guarantees, but if you go with an adoption agency with a good reputation, you can be almost certain you will become a parent. And once you make the decision, it is as if a rainbow appears. We call this our paper pregnancy, a child born in our hearts. Instead of running out of stores at the sight of a pregnant woman and avoiding the baby-product aisle at the market. I smile, hold my head up. I am on cloud nine.

Adoption entails logistical, emotional, and financial challenges. Though our options are often limited by finances, the requirements of adoption agencies and foreign countries, or the availability of children to adopt, learning about the various choices and being honest about whatever limits exist will help create a situation that will work for everyone.

My partner and I were present at the birth of our son, which we considered an incredible gift after years of infertility and a long adoption process. After a difficult birth, I was allowed to carry the baby to the neonatal unit, where he was measured and tested. It was in this intense moment that we learned that our birth mom had tested positive for drugs, so they were going to test our baby, too. I experienced an amazing tug of mixed emotions—I was furious at the birth mother for lying to us about her drug use and worried that the baby would have some problem that we weren’t prepared to take on . . . [The baby] also looked terrible—so huge and puffy from the birth mom’s untreated diabetes—and I worried whether I could love this ugly baby. Over the next few days, as it became clearer that the birth mom was going to follow through with the adoption, I still freaked out about my mixed feelings about the baby. Ironically, my partner, who had always been more ambivalent about being a mother, was the one who immediately and fiercely bonded with the baby. My feelings gradually resolved themselves as I spent time holding and talking to this little person in the NICU [neonatal intensive care unit], where he spent six days. He began to lose his puffiness and turned into my beautiful baby.

There are a number of things to think about in planning to adopt. How would you feel about having and maintaining contact with your child’s birth parents? Would you want to have a child who resembles you as much as possible, or would you embrace a child of another race or ethnicity? Do you want to adopt a newborn baby or an older infant or child? Are you willing to welcome a child with medical or emotional challenges? Are you open to parenting any child you are able to adopt?

The process of adoption can force us to confront complex ethical questions rarely considered by those who produce biologically related children: Why are home studies and other measures of parental fitness reserved only for adoption? How much control should we be allowed to exercise over the selection of a child? How can we be aware of, avoid, and work to prevent situations that might exploit or coerce birth mothers? How do we balance the potentially different needs of the child, birth parents, and adoptive parents regarding the degree of openness in adoption? Are those of us who live in wealthier nations “entitled” to raise children left homeless in other parts of the world by poverty or social stigma? How can we help our children deal with the racial, cultural, and identity issues they may face?

Many of us find it helpful to connect with a community of other adoptive and prospective adoptive parents or an adoption organization. They can answer questions, direct you to resources, and support you in the joys and frustrations of the adoption process. These groups are available in many cities, and many adoption websites offer online support.

Adoption is often an expensive process. To help offset the cost, the federal government provides a tax credit of up to $13,170 per child (as of 2011) to adoptive families; many states also provide tax credits or deductions. The military provides some reimbursement for adoptive families. Low- or no-interest loans are also available for adoptive families, and many employers offer adoption benefits.

The process of adoption can be an emotional journey. It is exciting to welcome our children, but there are also many times when we experience frustration, sadness, powerlessness, anxiety, and impatience. If you have been infertile, you may discover that adoption doesn’t “fix” that experience. You may be elated at finally becoming a mother, yet still grieve for the pregnancies you will never have.

If you come to adoption purely through choice or preference rather than infertility, your primary struggles are likely to be logistical. The time it takes to find your child can feel as though it will never end, and it is difficult to plan ahead.

Women entering parenthood through adoption need as much support as women who are pregnant. The logistics of your life, your sense of identity, and your relationships will all change. In addition, you face challenges unique to adoption. You won’t look pregnant, so you can choose not to discuss the ins and outs, ups and downs of your adoption process. On the other hand, others may discount your experience because they can’t see that you are in the process of becoming a parent. In addition, some people still have misunderstandings and negative judgments about adoption.

Parenting is hard work, both emotionally and physically. Our technological, fast-paced society does not serve the complex needs of parents and children, nor does it truly support and value caregiving within families. In order for women to balance the demands of family and work, we need a public commitment to family policies that make women’s and children’s needs a priority.

Child rearing is important and valuable work that deserves social and economic support. Whether or not we individually choose to have children, we all have a shared stake in the next generation and must work together to advance better family policies. For more information on the social policies that affect families, see “Being a Mother Today.”