8

The Reagan Intellectual Legacy

Americans are a free people, who know that freedom is the right of every person and the future of every nation. The liberty we prize is not America’s gift to the world; it is God’s gift to humanity.

—George W. Bush, “State of the Union Speech,” 2003

Time magazine contended in 1975, “Republicans now must decide whether he [Reagan] represents a wave of the future or is just another Barry Goldwater calling on the party to mount a hopeless crusade against the twentieth century.”1 In hindsight Reagan represented the future of the Republican Party, and maybe even America. His 1980 election bordered on a landslide. Furthermore the 1984 election was arguably the largest landslide in American history. Never has the Electoral College voted for anyone as overwhelming as it did for Reagan in 1984. In 1994 Reagan’s party took control of Congress for the first time in forty years. At the federal level, from 2002 to 2006 Republicans controlled the House, the Senate, and the presidency. They hadn’t controlled this much federal government for so long since the days of Teddy Roosevelt. And the same phenomenon occurred again in the wake of the 2016 elections.

Yet few figures divide people as Reagan does. Many may not realize this, but Ronald Reagan was the Donald Trump of his day. The first real conservative to be elected an American president (Nixon and Eisenhower were moderates), he is probably to the right of Trump on the ideological spectrum. His corresponding rhetoric and policies naturally evoked anger and hatred by segments of the American population. Reagan’s intellectual faculties too were questioned. He was considered dumb by some, senile by others. After he entered politics, some of his political opponents deemed him racist. And like Trump, he was called a warmonger because he postulated an aggressive foreign policy, used harsh rhetoric, and condemned arms reductions. The fate of the whole world seemed perilous during the Reagan years too.

These passions for and against Reagan naturally lead to strong biases. One biographer insists that writing about Reagan is not for the faint of heart, or the untenured.2 For twenty-second-century Reagan specialists studying secondary sources from this era, identifying the political affiliation of the author will matter. For many academics and scholars, the issues are personal. John Patrick Diggins contended, “The election of 1984 was a referendum on the 1960s.”3 If so, how did activists of the 1960s feel about Reagan? The writing of history can be very personal, often revealing more about the writer than the subject.

Interpreting the Reagan presidency often takes center stage in the battle between the American left and right. Jerry Sloan accurately wrote, “Conservatives recognize that the stakes of this interpretive conflict are high. The battle over Reagan’s legacy is really a struggle to determine America’s future. If the Reagan administration is perceived by the public as being successful, that increases the possibility of the new conservative leaders inheriting Reagan’s mantle and continuing his policies into the next century.”4 This is true, but it’s only half of the truth. Liberals equally understand the importance of the interpretive struggle; continuing their policies into the twenty-first century means denying any success to Reagan. Democratic senator Chuck Schumer contended, “We’re in better shape than [Republicans] are, because they don’t realize that Reaganomics is dead, that the Reagan philosophy is dead. . . . We realize that New Deal democracy, which is still our paradigm, which [sic] is sort of appealing to each group.”5 If Reagan’s ideas and tax cuts in fact stimulated economic growth and reduced unemployment, one of the central legs of the left-wing paradigm has been undercut. Moreover, if it becomes accepted that Reagan’s massive military expenditures led to the collapse of the Soviet Union, Republicans could use these historical examples to justify a large defense budget, a liberal nightmare. If it becomes conventional wisdom that Reagan’s tax cuts spurred economic growth, this would increase the appeal of Reaganesque candidates. This in turn would weaken other causes traditionally dear to liberals, such as environmentalism and abortion access. The left benefits by denying the overall success of the Reagan presidency, just as the right must promote his successes. Both sides have an equal stake in the debate.

When Obama lauded Reagan, he was instantly castigated by his fellow Democrats. The left-wing columnist Paul Krugman felt the need to tell “the truth about the Reagan presidency.” “Historical narratives matter,” insisted Krugman. “That’s why conservatives are still writing books denouncing F.D.R. and the New Deal; they understand that the way Americans perceive bygone eras, even eras from the seemingly distant past, affects politics today.” After explaining why conservatives must lambaste FDR, Krugman continued, “The Reagan economy was a one-hit wonder. Yes, there was a boom in the mid-1980s, as the economy recovered from a severe recession. But while the rich got much richer, there was little sustained economic improvement for most Americans. By the late 1980s, middle-class incomes were barely higher than they had been a decade before—and the poverty rate had actually risen.” After eight years of Reagan, he argued, most Americans were not better off.6 This narrative dominates the minds of Reagan’s political critics.

Three days after Reagan’s death, UC Berkeley eulogized him: “Ronald Reagan launched his political career in 1966 by targeting UC Berkeley’s student peace activists, professors, and, to a great extent, the University of California itself. In his successful campaign for governor of California, his first elective office, he attacked the Berkeley campus, cementing what would remain a turbulent relationship between Reagan and California’s leading institution for public higher education.”7 It’s important that UC Berkeley students know the truth about Reagan. “This was not a happy relationship between the governor and the university—you have to acknowledge it,” recalled Neil Smelser, a Berkeley professor of sociology. “As a matter of Reagan’s honest convictions but also as a matter of politics, Reagan launched an assault on the university.”8 Reagan dished it out just as well as he took it. As governor in 1966, he called UC Berkeley “a haven for communist sympathizers, protestors and sex deviants.”9

Conservatives have their own interpretation of Reagan, of course. Many conservatives deem him a demigod. He won the cold war, jump-started the American economy, and, most important, renewed American optimism. The conservative writer Dinesh D’Souza writes in his hagiography of Reagan that the 1980s were a time of technological innovation and advancement in the United States. Lou Cannon quantifies the period: “During the buying binge of the last six years of the Reagan administration, Americans purchased 105 million color television sets, 88 million cars and light trucks, 63 million VCRs, 62 million microwave ovens, 57 million washers and dryers, 46 million refrigerators and freezers, 31 million cordless phones and 30 million telephone answering machines.”10 Tax cuts enabled all of this, conservatives contend.

One of the greatest inventions in the history of humankind, the personal computer, proliferated, even becoming available to middle-class Americans in the mid-1980s. How does this relate to Reagan? D’Souza writes, “Where did all the venture capital for the new industries of the 1980s come from? There was a little of it around in the 1970s. George Gilder points out the number of major venture capital partnerships surged from 25 in the mid-1970s to more than 200 in the early 1980s. The total pool of venture capital nearly doubled, from $5.8 billion in 1981 to $11.5 billion in 1983.”11 This happened because Reagan poured hundreds of billions of dollars into private hands through his tax cuts, promoting investment in private companies, analogous to what today we call “start-ups.” The reasoning goes that wealthy Americans had more money, which they invested in technology. Seek the Kingdom of Freedom first, conservatives say, and then your material needs will be met. Computers, televisions, and airplanes are just some examples of the material benefits of freedom, and these have benefited all strata of society. Facebook, Google, Amazon, the iPhone, and Uber have emerged from the American economic system more recently.

Besides the reduction in taxes and the lowering of inflation and unemployment that followed Reagan’s tax cuts, as D’Souza contended, “when Reagan took office the poverty rate had been rising, from 11.4% to 14% in 1981. After climbing to a high of 15.2% during the recession of 1982, the poverty rate fell to 12.8% in 1989.”12 Under the Reagan presidency, the number of poor Americans declined. (This happens whenever the economy booms.) Conservatives thus believe that poverty was reduced as a result of Reagan’s tax cuts. Everyone benefits from freedom.

The Reagan Foundation has its own statistics:

- Twenty million new jobs were created.

- Inflation fell from 13.5 percent in 1980 to 4.1 percent by 1988.

- Unemployment fell from 7.6 percent to 5.5 percent.

- Net worth of families earning between $20,000 and $50,000 grew by 27 percent.

- Real gross national product rose 26 percent.13

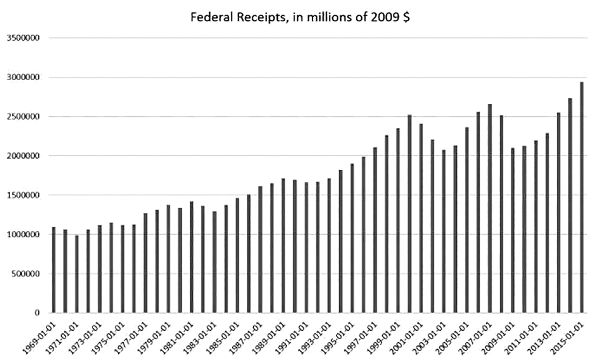

The last two stats concerning net wealth and GDP matter because they lead to more government revenue. Generally the more money people make, the more they pay in taxes. In 1980, 4,414 Americans filed tax returns with adjusted gross income of at least one million dollars. By 1987 that number had reached 34,944.14 Consequently, despite the fact that Reagan dramatically slashed the top marginal tax rate, the U.S. government actually collects more tax revenue per capita, adjusted for inflation, today than in 1980. Figure 1 demonstrates this.

America’s population is about 1.5 times greater now than in 1980, but our federal government is poised to collect more than 2 times more tax revenue (receipts), despite a significantly lower top marginal tax rate.

Fig. 1. 2009 Federal Receipts. Based on “Federal Recipts, in millions of 2009 $” from the article “Flush with Cash: US Government Collects Record Taxes in 2015” by Ryan McMaken, published online by the Mises Institute, April 25, 2016.

Given all of these statistics and different interpretations, is an objective study of Reagan even possible? Sean Wilentz, in his study of Reagan, contended, “Concerning the issues of objectivity and partisanship, I firmly believe that it is possible for a historian to lay aside personal views, commitments and earlier judgments when writing about the recent past—including events in which he or she has had a small hand.”15 Yet academics, scholars, and intellectuals work within a political paradigm, no different from the scientific paradigm described by Thomas Kuhn. We maximize and celebrate evidence that conforms to our value systems, while minimizing and trivializing evidence that contradicts our deepest, most fervent opinions. When Republican economic policies are followed by economic calamity (as under Hoover), they are celebrated as lessons of history regarding why we shouldn’t vote Republican. When they are followed by strong economic growth (as under Reagan), the evidence gets minimized and even dismissed, such as getting reduced to coincidence. Bias does not manifest itself through lies but rather by emphasizing evidence in such a way that it conforms to the individual person’s ideology. Like lawyers in a court case, historians selectively emphasize some evidence and de-emphasize the evidence they don’t like.

In his own work, for example, Wilentz denies that Reagan’s conservative policies had anything to do with the economic recovery of the mid-1980s. “Several factors led to the boom. In part (as David Stockman [one of Reagan’s budget directors] would later concede), the recovery was a normal phenomenon of the business cycle: the economy was bouncing back from Reagan’s own recession of 1981–1982.”16 Wilentz blames Reagan for the bad economy during the first two years of his presidency but gives him no credit for the booming economy during the rest of the decade, which gets reduced to normal business cycles. Blaming Reagan for the economic realities of 1981 is a bit unfair considering he didn’t even sign his tax cuts into law until August 1981, and they didn’t go into effect completely until January 1982. Reagan inherited a downward-spiraling economy. Other Reagan biographers have called the recession of 1981 and 1982 the “Reagan Recession.” Faulting Reagan for the recession of 1981–82 is as rational as blaming Obama for the bad economy in 2009 and 2010 (as some of those on the right did). Some analysis absolves Reagan of much of the blame for the bad economy in the first two years of his presidency, assuming historians don’t blame Obama for the poor job-creation numbers and rising unemployment of 2009–10. What about Reagan’s foreign policy? Wilentz lauds Reagan for successfully ending the cold war, calling it one of the great achievements in American presidential history.17 Nonetheless he calls the Reagan foreign policy “divided and contradictory.”18 Wilentz uses Iran-contra as evidence of Reagan’s foreign policy shortcomings.

When analyzing whether Reagan’s tax cuts helped improve the economy, it should be remembered that even Democrats in the early 1980s pushed for tax cuts as a way to jump-start the American economy. The difference between Reagan and Democrats in the early 1980s was not whether tax cuts were needed but rather how deep the cuts should go. Democratic leaders Dick Gephardt and Bill Bradley proposed reducing the top marginal tax rate in order to foster economic growth, but whereas Democrats wanted to reduce the top marginal tax rate from 70 percent to roughly 50 percent, Reagan wanted to reduce it to between 38 and 28 percent. Even the Obama stimulus package included tax cuts, proving that he was hardly a socialist who wanted to restrict all private property. The fear was inflation and increased budget deficits. Inflation actually plummeted. The drop in inflation since the 1980s is one of the most remarkable features of the American economy. To contextualize, in 1979 inflation was at 11 percent. In 1980 it was at 13.5 percent. In 1981 it was at 10 percent. Since 1983 inflation has never been over 5 percent. Since 1992 it has never been over 4 percent. This benefits poor and middle-class Americans more than anyone else. Although deficits soared, contrary to what many reasonably feared, the budget deficits had no long-term impact on the American economy: the 1990s was another decade of strong economic growth. Unemployment was lower, inflation was lower, and GDP growth was stronger than in the 1970s, an era with smaller deficits. In the 1980s fears that budget deficits would place great strain on America seemed rational, but in hindsight they were unfounded.

No one can say with certainty whether Reagan’s policies caused the drops in unemployment, surges in GDP, and reduced inflation, but historians generally grant agency to phenomena. For example, Napoleon, Lenin, and Hoover are just three of the figures in Western history to whom historians have granted agency for their economic policies, despite the fact that they had very different economic policies and different results. Historians don’t like the “That would have happened anyway” argument. Even the great Abraham Lincoln fell victim to this sentiment when his opponents argued that slavery would have died out without the Civil War, so it wasn’t really necessary after all. Yet historians don’t like coincidences; there is little point in studying the great figures in history if all of their achievements can be reduced to other causes. Presidential historians, in particular, must be willing to grant agency to presidents; otherwise there would be no point in ranking the presidents. If it were a foregone conclusion that America would claim the Louisiana territory, remain united after the Civil War, win World War I, World War II, and the cold war, and come out of the depression and the economic malaise of the 1970s, then no president should get any credit for his or her achievements. Yet we do know that presidential historians have favorites.

Moreover, it’s been over thirty years, and most of Reagan’s tax cuts are still in place. This is Reagan’s greatest domestic achievement. Even when Democrats have controlled the presidency and both houses of Congress, there have been no attempts to repeal Reagan’s tax cuts. His opponents can criticize all the changes that have taken place in America since 1980, but like FDR’s Social Security Act of 1935, Reagan’s tax cuts have become an integrated feature of American political culture. Their persistence is the best testament to their success. Historians use the existence of social security and the Great Society in the United States and the persistence of the welfare state in Europe as testimony to the success of left-wing parties there, but the same must be applied to Reagan. As long as the top marginal tax rate remains significantly below the 70 percent it was at when Reagan entered office, he can claim victory on this front. Some may dismiss his tax cuts on the grounds that they didn’t make America better, but Republicans maintain the same about social security and the Great Society.

In the Shadow of Reagan

Clearly Reagan cast a long shadow, longer than any other twentieth-century president, save FDR. American conservatives today descend from Reagan. And his influence has extended beyond the Republican Party. Peter Singer writes in a book on Karl Marx, “Nor has Marx’s influence been limited to communist societies. Conservative governments have ushered in social reforms to cut the ground from under revolutionary Marxist opposition movements.”19 American Democrats have adopted Reagan’s ideas to stop the spread of Reagan conservatives. President Bill Clinton adopted Reagan’s ideas. Welfare reform, fixing social security, a low top marginal tax rate, and NAFTA were all Reagan’s ideas, which many Democrats advanced in order to garner popular support. Did not President Clinton declare “The era of Big Government is over” shortly before winning reelection in 1996? Did not President Obama refuse a government takeover of the health care system, instead employing private health insurance companies to provide health insurance? Left-wing American governments have ushered in conservative ideas in hopes of curbing the influence of Reagan Republicans, or more precisely, to win back the support of Reagan Democrats, who are often swing voters. Republicans did and continue to do the same with Roosevelt.

William Leuchtenburg’s In the Shadow of FDR provided a model for this section. Leuchtenburg showed how each of FDR’s successors worked within the system FDR created. So forceful a figure was he, so powerful were his presidency and his ideas, that no one could escape his shadow. The same goes for Reagan. Presidential history following the two men’s presidencies is remarkably similar: both were succeeded by their vice presidents, who served only one full-term due to their unpopularity. Then came eight years of a moderate from the other party, Eisenhower and Clinton. Next came eight years of those who at least sought discipleship, JFK-LBJ and George W. Bush (although with all three, how much discipleship is debatable). Then came eight years of rule by the other party, Nixon-Ford and Obama (all three actually showed respect). Then came someone from the same party, Carter and Trump. This can’t all be coincidence.

George H. W. Bush and Reagan squared off in the contentious 1980 Republican primary. Whereas Reagan was a hardline conservative in the mold of Goldwater, Bush was a moderate, chiding Reagan’s plans for tax cuts, notoriously calling the ideas “voodoo economics.” Despite his experience in government and his early win in the Iowa caucus, Bush was quickly overwhelmed by the Reagan campaign. Reagan still named Bush his vice president (Ford was also considered), and the Reagan-Bush ticket convincingly won the 1980 presidential election. Bush kept a low profile as vice president and was naturally the front-runner for his party’s nomination for president. His résumé for the presidency seemed unimpeachable, including stints as ambassador to the United Nations and director of the CIA. He captured the presidency in 1988, winning 53 percent of the popular vote and 426 out of 537 electoral votes. It was a natural “third term” for Reagan.

Bush had to confront the budget deficits he inherited. Cuts (or slowed growth) to social programs and increases in tax revenue generated by the booming economy from about 1983 to 1989 didn’t make up for increased military spending in the early 1980s. With Democrats controlling both houses of Congress, Bush had to accept their ideas about raising the top marginal tax rate from 28 to 38 percent, thereby breaking his campaign pledge of “No new taxes.” Congressional Republicans, who by now were hailing Reagan as their hero, were furious. They never trusted Bush again. No real Reagan conservative, Bush violated rule number one of the conservative agenda: he raised taxes. Politically this was fatal. Even worse, recession followed, so by the middle of 1992 unemployment edged near 8 percent. Bush had angered Republicans by reneging on a crucial campaign promise just as America faced its first recession in ten years. This perfect storm helps us understand why Bush received only 37 percent of the popular vote in a three-way race in 1992.

Internationally, like Truman, Bush asserted American hegemony, proving that America would not retreat from world affairs, as it did after World War I and Vietnam. For Truman, the occasion was Stalin’s blockading of the American, French, and British sectors of Berlin in 1948. Stalin blocked Western access to Berlin by closing roads and railways in an effort to increase Soviet control of the city. Truman had to make a difficult choice: confront Stalin and risk World War III, or allow Stalin to incorporate all of Berlin into the Soviet Empire. Truman parried Stalin by orchestrating the Berlin Airlift. Demonstrating that America would not yield to Soviet pressures, the airlift was a key event in the early cold war. Berlin was distant, but America would not ignore Soviet expansion. For George H. W. Bush, the occasion was the first Gulf War. In 1991 President Saddam Hussein of Iraq launched a full-scale invasion of Kuwait, prompting the question, Should America take action and risk tens of thousands of lives or allow Saddam to control Kuwait? Now, largely thanks to the Reagan presidency, America could act militarily. The Reagan presidency, like the FDR presidency, initiated a new era in diplomatic history, one in which America reigned supreme, willing to wield its influence across the globe. The United States, leading a multilateral force, quickly pushed Saddam out of Kuwait. Operation Desert Storm was a smashing success, leading Bush to exclaim, “The specter of Vietnam has been buried forever in the desert sands of the Arabian Peninsula”20

American hegemony had returned. Truman and George W. Bush provided singular global leadership, yet despite their critical international successes, contemporaries across the political spectrum were disappointed by the Truman and Bush presidencies. For the members of their own parties, these two men could never live up to the standards set by their predecessors. Reagan and Roosevelt were tough acts to follow. Economic downturns during Truman’s and George H. W. Bush’s presidencies led to national pessimism and frustration, much of it naturally aimed at the incumbent. Both men left office victims of the mantra that it was time for change. (A similar phenomenon occurred during the Adams presidency. Following the great George Washington was an impossible task, and Adams became the first American president voted out of office.) Change was a central theme for both Eisenhower’s and Clinton’s first presidential campaigns.

The time to pay the piper had come. Sure, Reagan and Roosevelt scored landslide elections, but their successes were smoke and mirrors, their critics claimed. Roosevelt and Reagan were politically successful in the short term, but their long-term legacy was malignant. The best evidence for this came from the massive budget deficits both accrued, largely the result of defense spending in the midst of war. These irresponsible fiscal policies, many of Reagan’s critics pointed out, would saddle future generations with debt. Reagan’s biographer John Sloan admits the initial title of his 1999 Reagan biography was “The Reagan Presidency: Political Success and Economic Decline.”21

Reagan and FDR were suns; Truman and Bush, mere moons. Like Truman, Bush never adhered to the core principles of his predecessor; he never acquired the unmitigated support of the party of faithful because he, like Truman, was politically reared in the preceding era, so he wasn’t intellectually influenced by his predecessor. Truman wasn’t a Roosevelt Democrat; he was a product of the Pendergrast Machine, a powerful political organization in Missouri. And Bush, more in the mold of 1970s Republicans, was never a Reagan Republican. Nonetheless, to their opponents both men represented the colossus—a defeat of Truman meant an ex post facto defeat of FDR, while the left took the same view of the Bush administration’s political failings. By 1952 Republicans controlled both houses of Congress and the White House. The Roosevelt Revolution was over. By 1992 Democrats controlled the House, the Senate, and the presidency; all that had been gained during the Reagan years was lost. There was no real Reagan Revolution, as so many conservatives had hoped. The years 1952 and 1992 were years for change, with a new party given the opportunity to govern. It was about time, many believed.

First Democratic Interlude: Bill Clinton

We meet at a special moment in history, you and I. The Cold War is over. Soviet communism has collapsed and our values—freedom, democracy, individual rights, free enterprise—they have triumphed all around the world.

—Bill Clinton, “Address Accepting the Presidential Nomination at the Democratic National Convention in New York,” 1992

The unpopularity of their successors meant that Republicans after Roosevelt and Democrats after Reagan were given a chance to rule. To their opponents this meant that the United States had finally moved away from the policies of Roosevelt and Reagan and was ready to embark on a new course. Yet those who believed America would rid itself of the key components of the presidencies of Roosevelt and Reagan were naïve. It was under Clinton that some of Reagan’s ideas bloomed.

Clinton has been described as a man without a political compass, a man guided by public opinion polls. Even Clinton’s biggest defenders will acknowledge that he, unlike Reagan, lacked a comprehensive, consistent vision for America. Yet Clinton was in a quandary: his biggest supporters despised Reagan, yet much of the American center—those most responsible for determining who wins and who loses elections—were Reagan Democrats. So Clinton walked a fine line. After becoming governor of the conservative state of Arkansas in 1978, he adapted to the conservative winds blowing across America by joining the newly formed Democratic Leadership Council, an organization that contended the Democrats should abandon far-left ideas. He became chairman in 1990 and campaigned in 1992 as a “New Democrat,” promised to “end welfare as we know it,” and stressed the need to reform social security. Apparently he had learned the lessons of the Republican victories in 1980, 1984, and 1988, the first time either side had won three straight elections since the days of FDR. Clinton won the 1992 election relatively easily, capturing 43 percent of the popular vote in a three-man race.

Clinton’s acceptance speech for the Democratic nomination plagiarized some of Reagan’s vision for America and the world. He contended that freedom, democracy, individual rights, and capitalism are not American values; they are universal values, applicable to all societies:

Soviet communism has collapsed and our values—freedom, democracy, individual rights, free enterprise—they have triumphed all around the world. [Everywhere around the world, the cry is for liberty, Reagan said.]

Tonight 10 million of our fellow Americans are out of work. Tens of millions more work harder for lower pay. The incumbent President says unemployment always goes up a little before a recovery begins, but unemployment only has to go up by one more person before a real recovery can begin. And Mr. President, you are that man. [Reagan joked in 1980, “Recession is when your neighbor loses his job. Depression is when you lose yours. And recovery is when Jimmy Carter loses his.”]

That’s why we need a new approach to government, a government that offers more empowerment and less entitlement, more choices for young people in the schools they attend—in the public schools they attend. . . . A government that is leaner, not meaner; a government that expands opportunity, not bureaucracy; a government that understands that jobs must come from growth in a vibrant and vital system of free enterprise. [Reagan said in his Inaugural Address in 1981, “Government can and must provide opportunity, not smother it; foster productivity, not stifle it.”]22

Capitalism promotes economic growth and productivity, not a government bureaucracy. The private sector and freedom create material wealth. Clinton declared that what was needed was “an America that says to entrepreneurs and businesspeople: We will give you more incentives and more opportunity than ever before to develop the skills of your workers and to create American jobs and American wealth in the new global economy. An America where we end welfare as we know it. We will say to those on welfare: You will have and you deserve the opportunity through training and education, through child care and medical coverage, to liberate yourself. But then, when you can, you must work, because welfare should be a second chance, not a way of life.”23 The far-left argued that labor creates economic growth and value, but Clinton focused on the creative classes. No Democrat would adopt so many ideas of George W. Bush, nor would a Republican mimic Clinton. However, just as no political figure in the post–World War II years could ignore FDR’s shadow and legacy, the same can be said for Reagan’s ideas. Even his antagonists must capitulate because his ideas have become ingrained in American political culture. Reagan’s opponents criticize parts of his philosophy, but overall their attitude must be described as ambivalent.

The Democrats swept the 1992 elections, capturing key southern states that had voted for Reagan. In doing so the Democrats won the presidency for the first time since 1976 and even gained seats in the House. Time magazine called the results of the election “a mandate for change.”24 (Eisenhower titled his biography about his first term as president A Mandate for Change.) Despite Clinton’s “New Democrat” pretensions, many interpreted the election as a victory for old-style liberalism and a defeat of Reaganism. The Clinton administration initially lurched far to the left. In his first two years in office, there was no effort to reform welfare. Taxes were raised, although the top marginal tax rate was only raised to 43 percent, far below where it was before Reagan took office. Clinton also introduced the holy grail of liberalism, government-run universal health care. The Health Security Act of 1993, spearheaded by Hillary Clinton, was defeated, even with a Democrat-controlled House and Senate. Clinton didn’t heed Reagan’s warnings about a government takeover of the entire health care system.

American voters voiced their opposition to Clinton in the 1994 midterm elections. In a mini-revolution, Republicans took control of the House of Representatives for the first time in forty years. (Democrats took back control of the House in 1954, after their 1952 fiasco.) The Reagan presidency had changed many congressional districts from blue to red. The new conservative manifesto was the “Contract for America,” much of it modeled upon Reagan’s 1985 State of the Union address. Specifically the contract attempted to shrink divisions between the people and their government. Term limits, reducing the size of government, and auditing fraud and waste were all part of the contract. More significant, the contract promised to cut taxes on businesses and individuals, as well as enact some sort of social security and welfare reform. After a two-year hiccup, Reagan was back.

Accordingly a new Bill Clinton emerged after 1994, a more moderate Clinton, a Clinton willing to implement some of Reagan’s ideas. Like Eisenhower, Clinton attempted and succeeded at placing himself above the political fray. Now he was neither liberal nor conservative; instead he combined the best elements of each philosophy. Clinton triangulated by rising above the political extremes. Just as Ike was no FDR disciple, Clinton was no disciple of Reagan, yet each was politically astute enough not to refute certain principles. This allowed Clinton to capture the support of the American center. In his 1996 State of the Union address, Clinton famously proclaimed, “We will meet these challenges, not through big government. The era of big government is over, but we can’t go back to a time when our citizens were just left to fend for themselves.”25 Government, he contended, was not the solution.

Clinton even adopted the social security position that Reagan had been arguing for decades. He recognized the inherent flaw in social security, and by the 1990s many Democrats agreed that the program needed fixing. At a speech given in Georgetown, Clinton described the impending “crisis”: “If you don’t do anything, one of two things will happen. Either [social security] will go broke and you won’t ever get it, or if we wait too long to fix it, the burden on society . . . of taking care of our generation’s social security obligations will lower your income and lower your ability to take care of your children to a degree that most of us who are parents think would be horribly wrong and unfair to you and unfair to the future prospects of the United States.”26

Clinton embraced Reagan’s ideas about welfare reform too. By the middle of the 1990s there was a concerted effort by those on both sides of the aisle to reduce the number of people on welfare. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act of 1996 implemented many of Reagan’s ideas about tightening welfare by limiting the number of years a person could receive welfare consecutively to two, and overall to five. Also, the program became more decentralized. Money was dispersed by states through block grants. The 1996 Democratic platform bragged, “Welfare rolls are finally coming down—there are 1.8 million fewer people on welfare today than there were when President Clinton took office in January 1993. . . . The new welfare plan gives America an historic chance: to break the cycle of dependency for millions of Americans, and give them a real chance for an independent future. It reflects the principles the President has insisted upon since he started the process that led to welfare reform.”27 Many liberals condemned Clinton, and even key members of his cabinet voiced opposition. But minds began to change, shifting from outright opposition to ambivalence or even modest support. The numbers of those dependent on welfare declined significantly, and there was no corresponding rise in poverty. The left-leaning New Republic admitted in 2006, “A broad consensus now holds that welfare reform was certainly not a disaster—and that it may, in fact, have worked much as its designers had hoped.”28 Like social security, welfare reform will always have ideological opponents, but the persistence of the program—even during times of Democratic majorities—suggests that the pros outweigh the cons.

NAFTA is another Reagan idea that Clinton embraced and ran with. This agreement, consistent with the classical economic theory favored by Reagan, eliminated trade barriers between the United States, Canada, and Mexico. It immediately eliminated tariffs on 50 percent of Mexican exports to the United States and over 30 percent of American exports to Mexico. Clinton maintained, “For decades, working men and women and their representatives supported policies that brought us prosperity and security. That was because we recognized that expanded trade benefited all of us but that we have an obligation to protect those workers who do bear the brunt of competition by giving them a chance to be retrained and to go on to a new and different and, ultimately, more secure and more rewarding way of work.”29 Some resisted NAFTA, arguing that free trade benefited only the economically powerful; instead these people yearned for “fair trade.” Still, the Obama administration made no effort to renegotiate NAFTA. Trump has voiced opposition to parts of NAFTA, but it remains to be seen what changes will be made.

Internationally, Clinton sent the U.S. military globetrotting, something Ford and Carter refused to do in the wake of Vietnam. There have been four presidents since Reagan, and each has sent soldiers and dropped bombs all over the world. Whether it be the first Gulf War, Clinton’s efforts in the former Yugoslavia and Somalia, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, or more recent efforts by Obama in Syria and Libya, Reagan enabled this. Whereas the post-Vietnam years saw a reluctance to use the American military to fight the evils of the world, after Reagan both Democrat and Republican presidents have used the military that Reagan reconstructed to help solve the world’s problems. Vietnam syndrome is dead. And Reagan killed it.

Finally, and maybe most significant of all, Clinton embraced Reagan’s ideas about the universal applicability of American democracy, even to Iraq. Clinton maintained in 1998, “The United States wants Iraq to rejoin the family of nations as a freedom-loving and law-abiding member. This is in our interest and that of our allies within the region. The United States favors an Iraq that offers its people freedom at home. I categorically reject arguments that this is unattainable due to Iraq’s history or its ethnic or sectarian makeup. Iraqis deserve and desire freedom like everyone else.”30 Reagan’s influence is obvious; such ideas would have been impossible before his presidency or the fall of the Soviet Union. Clinton’s role in creating a political climate conducive to war in Iraq has been underestimated, probably because the war’s biggest critics voted for him. But Clinton plays an intermediary role between Reagan’s belief that all people of the world deserved freedom and that America must promote this, and George W. Bush’s attempt to apply this to Iraq. It was Clinton who in 1998 signed the “Iraq Liberation Act,” making regime change the official U.S. policy toward Iraq. By the end of that year Clinton had ordered a sustained bombing campaign of Iraq, insisting that Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction threatened American security.31 Clinton argued, “The hard fact is that so long as Saddam remains in power, he threatens the well-being of his people, the peace of his region, the security of the world. . . . If Saddam defies the world and we fail to respond, we will face a far greater threat in the future. Saddam will strike again at his neighbors. He will make war on his own people.”32 Clinton and Reagan both helped pave the road that George W. Bush traveled. The stage was now set for an invasion of Iraq under the auspices of national security, partly inspired by the desire to spread the Kingdom of Freedom.

George W. Bush and the War in Iraq: Betrayal or Continuance?

By the mid-1990s Reagan, the man accurately described as a “one-man think tank,” became intellectually impaired. Alzheimer’s disease robbed him of most of his cognitive faculties, so he could no longer speak about national and foreign issues, as he had for the preceding fifty years. Now those who followed Reagan, his disciples, were left on their own to interpret his thought. Like all significant intellectual figures, Reagan has heirs and divisions exist among them; they even consider themselves rivals. In Reagan’s case, the divisions are between neoconservatives and more traditional conservatives, sometimes called “paleoconservatives.” Reagan inspired both; each claim to be his true heirs. This is normal in the history of thought.

Neoconservatism is sort of an inverted Marxism. It tries to export democracy instead of socialism. Whereas Marx viewed the advent of world socialism to be inevitable, neoconservatives similarly view Western-style democracy. In fact, some early neoconservatives were weaned on Marxist or, more precisely, Trotskyist dogma, which promoted worldwide or ecumenical worker revolution, as opposed to the more provincial “socialism in one country” preached by Stalin. In the 1920s Stalin argued that the Soviet Union needed to strengthen itself before promoting worldwide revolution, but Trotsky argued for “permanent revolution,” or the belief that socialists needed to promote revolution everywhere, even in countries with primitive economic systems. Neoconservatives merely substitute democracy for socialism. Marxism-Leninism-Trotskyism descends from Christianity, so the fact that many figures on the right, like Reagan, can recast these ideas as their own is reasonable.33

Neoconservatism needs to be contextualized. It emerged after World War II, after the destruction of Nazism, largely thanks to the American military. Neoconservatives were anticommunist and believed that America needed to take an active role in the world in order to stop the spread of communism, as America did with Nazism, so they are hawks. Taking its cue from the first two world wars, American international activism defines neoconservatism, as opposed to the isolationism that America practiced between the two world wars. Neoconservatives thus hail Truman as one of their own. After World War II, Truman ensured that the United States would not revert back to the isolationist period of the 1920s and 1930s. Against popular opinion, he argued that American involvement was needed in Greece, lest communism spread there. Freedom was the issue for Truman, and he felt it was America’s responsibility to “support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures,” such as the Soviet Union. He continued, “If we falter in our leadership we may endanger the peace of the world—and we shall surely endanger the welfare of our nation.”34 “Americans,” Truman declared at another time, would use “our military strength solely to preserve the peace of the world. For we now know that this is the only sure way to make our own freedom secure.”35 In 1950, after North Korean communists crossed the thirty-eighth parallel into democratic South Korea, Truman ordered hundreds of thousands of American servicemen to Korea, starting the Korean War. Over fifty thousand Americans perished.

Nonetheless, neoconservatives hail Truman’s activism and adopt Reagan’s faith in the military, something Republicans were less inclined to do before Reagan. In the twenty-first century the Republican Party is associated with defense spending, but that hasn’t always been the case. A Democrat brought America into World War I. FDR engaged in the largest peacetime military buildup in American history, earning him criticism from Republicans for being a warmonger. Roosevelt’s leading congressional opponent was Republican Robert Taft, an isolationist who opposed any American involvement in Europe during World War II, until Pearl Harbor. After FDR’s death, Taft tried to thwart Truman’s attempt to bring America into the NATO Alliance. Truman remains the only leader in history to use the most deadly weapon in world history, the atomic bomb. Truman started the Korean War. It was ended by Eisenhower, the same Republican who coined the term “military-industrial complex” because he feared the cost of an arms race. What prompted him to make such statements as he left office? His successor, John F. Kennedy, insisted during the 1960 presidential campaign that the Eisenhower-Nixon administration had allowed a “missile gap” to develop between the United States and the Soviet Union, something he vowed to erase. LBJ greatly escalated American involvement in Vietnam. After initially expanding the Vietnam War, his Republican successor wound it down. Nixon and Ford both cut military spending in the post-Vietnam years. Senator Scoop Jackson, an ardent cold warrior militarist during the 1960s and 1970s, was a Democrat. The point is, the Republican Party hasn’t always been the hawkish party that invests more heavily in the military. This demonstrates Reagan’s influence on the contemporary conservative mind: the American military can and must be used to make the world a better place. These efforts are always noble and, if successful, never in vain.

Neoconservatism gained more traction after the fall of the USSR. One of the lessons of the most historically significant event of the second half of twentieth century is that geography doesn’t restrict freedom and democracy. The fall of the Soviet Union gave neoconservatives great confidence in their core values, since it suggested that they had been right all along: America must play a key role in exporting democracy, a universal principle. To neoconservatives Reagan’s hawkish foreign policy played a direct role in undermining the Soviet system. A cursory overview of the second half of the twentieth century reveals that America successfully promoted democracy in Germany, Japan, and Eastern Europe. The Middle East was next. Neoconservatives found safe haven in the George W. Bush administration. At first blush, Bush’s presidency merely continued Reagan’s: a foreign policy aimed at liberating people from tyrants and spreading Western notions of freedom, an economic policy focused on tax cuts, and a socially conservative, theologically inspired agenda. Who else would W look to as a model? Certainly not his father, a one-term president. The political debt that George W. Bush owes to Reagan scarcely needs to be mentioned; had there been no Reagan, there would have been no George W. Bush presidency.

After winning one of the most hotly contested elections in American history, Bush initially focused on domestic issues, mostly out of necessity because he inherited a struggling economy as the dot-com bubble burst. Bush responded by signing the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001. In accordance with Reagan’s policies, it tried to jump-start the American economy through tax relief. Tax rates for all classes were reduced. Unrelatedly, in the summer of 2001 the No Child Left Behind bill was signed into law. Passed with lots of Democratic support, it aimed at incentivizing and increasing federal spending on education, particularly among poor and minority students. Contra Reagan, it expanded the role the federal government played in education. Bush’s focus on domestic issues was short-lived, however.

The attacks on September 11, 2001, led to a new American foreign policy. As commander in chief of the U.S. Armed Forces, President Bush swore that America would respond. His initial rhetoric emulated Reagan’s interpretation of the cold war: “Tomorrow, when you get back to work, work hard like you always have. But we’ve been warned. We’ve been warned there are evil people in this world. We’ve been warned so vividly. . . . My administration has a job to do and we’re going to do it. We will rid the world of the evil-doers.”36 The enemy seemed different, but the perpetual conflict of good versus evil remained. Communism, Nazism, and Al Qaeda might seem like entirely different entities, but they really aren’t, Bush held, because they all descend from the same source. The “War on Terror,” in essence, was merely the latest manifestation of the conflict between good and evil. It was as old as humanity. The United States responded by invading Afghanistan because it provided safe haven for the mastermind of the 9/11 attack, Osama bin Laden. Within days and with broad support, American military forces pounded the Taliban regime for its complicity in the attack. Yet 9/11 revealed America’s vulnerability. The world contained unimaginable threats, and dictatorships in distant lands did, in fact, threaten the peace and security of the United States. America had forgotten the lessons of appeasement and paid the price, again. In hindsight the United States should have taken a more active role in Afghanistan, doing whatever it could to overthrow the regime that abetted Al Qaeda prior to 9/11. President Bush learned the lessons of history and would not make the same mistake in Iraq. Iraq repeatedly violated international law, practiced an expansionist foreign policy, and its leader committed acts of genocide when sarin gas was used against the Kurds in 1988. The Bush administration, with the support of roughly one-third of the world and slight majorities in Congress and the American public, launched an invasion of Iraq in March 2003.

In the tradition of Reagan, Bush argued that those who oppose the war had not learned the lessons of history, namely appeasement. Bush’s critics argued that he did not learn the lessons of history, specifically Vietnam. The issue is, which lesson of history matters? The Bush administration mimicked the Reagan administration by warning against appeasement to buttress its case for war in Iraq. Finding analogies between Hitler and Saddam was easy: besides being brutal tyrants who sought territorial aggrandizement, both flagrantly violated and ignored international law following their nation’s defeat in war. After World War I, Hitler disregarded the Versailles Treaty by reconstructing the Nazi Wehrmacht. Following defeat in the first Gulf War, the United Nations imposed restrictions on Iraq, which Saddam disregarded. Resolution 1441 was passed unanimously in November 2002; everyone agreed that Iraq had violated resolutions 686, 687, 688, 707, 715, 986, and 1284. If Iraq did not comply, Resolution 1441 promised “serious consequences,” which most knew meant war. One of the reasons the Bush administration publicly used Resolution 1441 to justify invading Iraq is because it conformed perfectly with the appeasement era of the 1930s.

Inspired by the success of Reagan’s foreign policy, Bush’s foreign policy aimed at defeating evil and spreading democracy to oppressed peoples. Continuing Reagan’s idea about the moral supremacy of freedom, Bush argued that spreading freedom was a strategic move: “The United States has no quarrel with the Iraqi people; they’ve suffered too long in silent captivity. Liberty for the Iraqi people is a great moral cause, and a great strategic goal. The people of Iraq deserve it; the security of all nations requires it. Free societies do not intimidate through cruelty and conquest, and open societies do not threaten the world with mass murder. The United States supports political and economic liberty in a unified Iraq.”37 Seek the Kingdom of Freedom first, and all your earthly desires will be met.

For Bush, freedom and religion are not distinct concepts; one logically follows from the other. They are inexorably bound. He declared, “I have a message for the brave and oppressed people of Iraq: Your enemy is not surrounding your country, your enemy is ruling your country. And the day he and his regime are removed from power will be the day of your liberation. . . . Americans are a free people, who know that freedom is the right of every person and the future of every nation. The liberty we prize is not America’s gift to the world; it is God’s gift to humanity.”38 The Kingdom of Freedom will continue to march triumphantly. The “enemies of freedom” will have their moments—the Kingdom of Freedom never arrives without struggle and conflict—but in the end, we will win. Hitler spread evil from 1933 through 1945. Initially violence, death, and destruction overwhelmed Germany, but ultimately this yielded a better Germany, a Germany with more freedom. The American Revolution and the French revolutions of 1789, 1830, and 1848 were all violent struggles, but they led to freedom. The birth of freedom in Japan was preceded by the dropping of two atomic bombs on the island nation. History teaches us that death and destruction are sometimes necessary preconditions to freedom.

Despite demands for freedom in Eastern Europe and China and freedom’s success in Muslim Indonesia, some still rejected Reagan’s and Bush’s idea that freedom and democracy are universal values. A writer in the the New Yorker, for example, contends:

Democracy is a wonderful idea, but none of the countries in the Middle East, except Israel and Turkey, resemble anything that would look like a democracy to Americans. Some Middle Eastern countries are now and have always been ruled by monarchs. Some are under the control of an ethnic or religious group that represents a minority of the population. Saudi Arabia and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan are the world’s only major nations named after a single family, and in Saudi Arabia the royal family functions as, in effect, the country’s owner. Most Middle Eastern countries don’t even make the pretense of having freely elected parliaments; in Iran, for example, candidates have to be approved by the mullahs.39

Applying postmodernist arguments, they asserted cultural relativity and appreciation. Bush countered, “There was a time when many said that the cultures of Japan and Germany were incapable of sustaining democratic values. Well, they were wrong. Some say the same of Iraq today. They are mistaken. The nation of Iraq, with its proud heritage, abundant resources and skilled and educated people, is fully capable of moving toward democracy and living in freedom.”40 Japan, Russia, and East Germany prove that freedom is not a Western value but a universal value, longed for and deserved by all people of the world. If democracy can succeed in East Germany and Japan, it can flourish anywhere, including Iraq. Ecumenism permeates neoconservatism. Bush asserted in 2006:

Five years ago, Iraq’s seat in this body [United Nations Assembly] was held by a dictator who killed his citizens, invaded his neighbors and showed his contempt for the world by defying more than a dozen U.N. Security Council resolutions. Now Iraq’s seat is held by a democratic government that embodies the aspirations of the Iraq people. It is represented today by President (Jalal) Talabani. With these changes, more than 50 million people have been given a voice in this chamber for the first time in decades. Some of the changes in the Middle East are happening gradually, but they are real. Algeria has held its first competitive presidential election, and the military remained neutral. The United Arab Emirates recently announced that half of its seats in the Federal National Council will be chosen by elections. Kuwait held elections in which women were allowed to vote and run for office for the first time. Citizens have voted in municipal elections in Saudi Arabia and parliamentary elections in Jordan and Bahrain and in multiparty presidential elections in Yemen and Egypt. These are important steps, and the governments should continue to move forward with other reforms that show they trust their people.41

Everywhere around the world, the cry was for liberty. Reiterating Condorcet’s ideas, Bush asserted that no nation transitions easily to democracy: “Every nation that travels the road to freedom moves at a different pace, and the democracies they build will reflect their own culture and traditions.”42 Bush was not naïve to cultural differences; he just subordinated them to freedom. For better or worse, even in the midst of violence, there was no equivocation. Political pundits may conveniently portray Bush and Obama as adversarial figures, yet spreading democracy to the Middle East has played an important role in both of their presidencies. Like Reagan, Bush and Obama have asserted that the victory of democracy is inevitable.

Naturally President Bush hoped history remembers him as a liberator: “I’d like to be a president [known] as somebody who liberated 50 million people and helped achieve peace.”43 An entire chapter of the Iraqi Constitution (2005) is dedicated to “Liberties.” Parts of it read: “The liberty and dignity of man are safeguarded.”

Article 37:

- First: The freedom of forming and of joining associations and political parties is guaranteed. This will be organized by law.

Article 38:

- The freedom of communication, and mail, telegraphic, electronic, and telephonic correspondence, and other correspondence shall be guaranteed and may not be monitored, wiretapped or disclosed except for legal and security necessity and by a judicial decision.

Article 39:

- Iraqis are free in their commitment to their personal status according to their religions, sects, beliefs, or choices. This shall be regulated by law.

Article 40:

Article 42:

- First: Each Iraqi enjoys the right of free movement, travel, and residence inside and outside Iraq.

- Second: No Iraqi may be exiled, displaced or deprived from returning to the homeland.

Article 43:

- There may not be a restriction or limit on the practice of any rights or liberties stipulated in this constitution, except by law or on the basis of it, and insofar as that limitation or restriction does not violate the essence of the right or freedom.44

Foner wrote in 1998, “The United States fought the Civil War to bring about a new birth of freedom, World War II for the Four Freedoms and the Cold War to defend the free world.”45 To this one may now add the Iraq War, to spread freedom. The Iraq War could be interpreted as a logical continuation of American and Western history: American freedom triumphed in World War II and the cold war, so in our age of unprecedented hegemony, spreading these ideas, using our seemingly unlimited power to spread our values, is hardly a big leap. It may be the nature of powerful civilizations to export their culture, irrespective of any human desire. Bush may represent the most powerful person in the world spreading its most powerful idea. Hegel maintained that every age has its ideas and individuals who spread them, and they are unconscious of their deeper motivations. This isn’t a coronation of President Bush because Hegel contended these figures don’t have to be loved.

Wars in Afghanistan and Iraq highlighted a divide between Reagan Republicans, those who fashion themselves as neoconservatives and paleoconservatives. Both claim to be Reagan’s true heirs. Despite the fact that Bush used Reagan’s ideas to justify the war in Iraq, paleoconservatives assert that he misinterpreted Reagan. More isolationist in nature, they argue that Reagan would have opposed the invasion of Iraq. Every dollar spent on Iraq—and the number of dollars spent exceeded one trillion—is a dollar that could be put back in the pockets of regular Americans. Reagan avoided using force to accomplish his diplomatic goals. The defeat of the Soviet Union did not follow a military conflict. Kirk, for example, wrote regarding the first Gulf War, “Unless the Bush administration abruptly reverses its fiscal and military course, I suggest, the Republican Party must lose its former good repute for frugality, and become the party of profligate expenditure, ‘butter and guns.’ And public opinion would not long abide that. Nor would America’s world influence and America’s remaining prosperity.”46Lamenting the material costs of the first Gulf War and the rise of neoconservatism, Kirk supported Pat Buchanan in his 1992 primary challenge against George H. W. Bush

Was Reagan an inchoate neocon? Diggins didn’t think so. He lauded Reagan, calling him, along with Lincoln and Roosevelt, one of the three great liberators in American history. Diggins believed Reagan played a pivotal role in orchestrating the collapse of the Soviet Union and ultimately the American victory in the cold war, but how he achieved this liberation was key for Diggins. While Lincoln and Roosevelt resorted to violence and ultimately the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Americans in order to achieve liberation, Reagan, to his credit, won the cold war peacefully, specifically through his personal negotiations with Gorbachev. Reagan, unlike modern neoconservatives, did not use war to bring down the Soviet Union, nor did he want war. He abhorred nuclear weapons and insisted that a nuclear war could never be fought. The Strategic Defense Initiative, after all, was a defensive measure aimed at preventing nuclear attack. His personal meeting with Gorbachev, not his military buildup, created favorable conditions for Soviet reform and ultimately Soviet collapse. Diggins quoted from an essay claiming there was “not a shred of evidence” that the U.S. military buildup had anything to do with Soviet reform.47 This was designed to undermine neoconservatism.

Cannon was unequivocal. “So no, Reagan wouldn’t have gone into Iraq,” he declared in his study of the relationship between Bush and Reagan.48 I really don’t know if he is correct, but to play devil’s advocate, Reagan did argue, “There is a profound moral difference between the use of force for liberation and the use of force for conquest,” so clearly the invasion of Iraq is not akin to Hitler’s invasion of Poland.49 The problem with communism from Reagan’s perspective was that it denied freedom, and this can be applied to Iraq. And if Reagan called Vietnam a “noble cause,” then isn’t Iraq also a noble cause? Iraq was less costly to the United States than Vietnam. At least Bush succeeded in toppling tyranny and establishing democracy, something the architects of the Vietnam War never achieved. It remains to be seen whether democracy will succeed in Iraq, but the effort in Vietnam failed.

And Reagan was willing to use force and violence to spread freedom, albeit on a much smaller scale. The island of Grenada became another hot spot in the cold war and really gave Reagan his first chance to apply his ideas to the world. In October 1983 the United States invaded Grenada in an effort to overthrow a Marxist government. It succeeded, with nineteen Americans killed in action. It was America’s first military victory since Vietnam, and it was the first time that a Marxist government had been replaced by a pro-American one. Reagan did maintain that freedom is worth dying for. Moreover those who say that Reagan would have opposed the Iraq War ignore that no international event shaped his geopolitical philosophy more than the appeasement era and that the similarities between Iraq and Nazi Germany were clear.

How would Reagan have handled the situation in Iraq? This is like asking, “Would Marx have supported the Russian and Chinese revolutions?” Lenin and Mao thought so. Would JFK have escalated American involvement in Vietnam? Johnson certainly believed so. After all, didn’t Kennedy promise to bear any burden to defend liberty? Would Reagan have supported the Iraq War? The true answer is, who knows? The biographer cannot answer a question that the subject of the biography has not even remotely addressed. Reagan’s ideas certainly contributed to these events, even if they have been misinterpreted. Iraq did not deviate from Reagan’s geopolitical philosophy, namely the idea that America should seek to spread freedom around the world. Any history of the idea that America has a right and an obligation to overthrow tyranny and spread liberty must include Reagan.

Many scholars draw parallels between American conservatives and Jefferson’s ideas about limited government, but Jefferson’s ideas about freedom and the broader world historical picture helped shaped supporters of the Iraq War. Jefferson, in the midst of the outlandish violence that characterized the “Reign of Terror” phase of the French Revolution, nonetheless defended the Revolution. This was a bold stand in 1794, but Jefferson insisted, “The liberty of the whole of earth was depending on the issue of that contest.” Jefferson didn’t support the violence, but the French Revolution, like the American Revolution, attempted to overthrow tyranny and replace it with republicanism, so it was an encore to the American Revolution. Death, destruction, and violence were necessary preludes, he felt, for a better world. He believed that American principles could be transplanted to other parts of the world. He predicted, “This ball of liberty, I believe most piously, is now so well in motion that it will roll around the globe.”50 Jefferson’s intellectual kinsman, Thomas Paine, also drew connections between the American and French revolutions, insisting each had established “universal rights of conscience, and universal rights of citizenship.” Paine emphasized a “school of freedom” that originated in the Enlightenment and was now blooming in these democratic and republican revolutions, even going so far as to argue that hereditary governments would one day disappear from the earth, replaced with republican forms of government, as mankind becomes more enlightened. Paine, in accordance with Enlightenment principles, insisted that one day all of the world would live in freedom.51 Iraq can be placed in this context.

Paine partly attempted to refute the most famous and influential opponent of the French Revolution, Edmund Burke. In 1790, one year after the French Revolution, Burke, a father of traditional conservatism, wrote a very early history of the Revolution entitled Reflections on the Revolution in France. He argued that by creating a society based on abstract principles, the leaders of the French Revolution were ignoring the complexities of human nature. Fundamentally he was an empiricist, castigating the rationalist underpinnings of the French Revolution. Like many critics of Iraq, Burke did not oppose liberty or even the spread of liberty to France; rather he opposed how the French went about achieving their freedom. The works of the philosophes provided an unstable foundation for the project. Burke predicted collapse. In the short term Burke was right, and near his death Jefferson acknowledged this. It should be pointed out that the “short term,” in this case, was about twenty-five years. In the long run, Jefferson was right: the French people thrive under republicanism, based on the theory that all men are equal and entitled to freedom.

Jefferson’s foremost antagonist, John Adams, never saw a relationship between the French revolutionaries and the crew of 1776. Siding with Burke, Adams argued that American principles could never succeed in France. He insisted that a republican form of government had the same chance of succeeding as a snowball in the Philadelphia sun.52 As it did so often, round 1 went to Adams, but Jefferson ultimately prevailed because today, historians lump the American and French revolutions together. History books describe these tumultuous events in the same chapter, a victory for Jefferson.

What about George W. Bush’s domestic policy? Did this descend from Reagan, in means and ends? Some leading conservatives argued Bush has betrayed Reagan in this realm too. He has been classified as a “Big Government Republican” because he expanded every federal department. Pat Buchanan complained:

What killed the first Bush presidency and is ruining the second is the abandonment of Reaganism and his embrace of the twin heresies of neo-conservatism and Big Government Conservatism, as preached by the resident ideologues at The Weekly Standard and Wall Street Journal. Under Bush I, taxes were raised, funding for HUD [U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development] and Education exploded, and a quota bill was signed under which small businesses, accused of racial discrimination, were made to prove their innocence, or be punished, in true Soviet fashion. . . . Under Bush II, social spending has exploded to levels LBJ might envy, foreign aid has been doubled, pork-at-every-meal has become the GOP diet of choice, surpluses have vanished, and the deficit is soaring back toward 5% of GDP. Bill Clinton is starting to look like Barry Goldwater. . . . When Ronald Reagan went home to California, his heirs said, “Goodbye to all that” and embraced Big Government conservatism, then neo-conservatism. If they do not find their way home soon, to the principles of Taft, Goldwater and Reagan, they will perish in the wilderness into which they have led us all.53

In his work Imposter: How George W. Bush Bankrupted America and Betrayed the Reagan Legacy (2006), Bruce Bartlett wrote, “Traditional conservatives [e.g., Reagan] view the federal government as being untrustworthy and undependable. They use it for only necessary functions like national defense. . . . George W. Bush, by contrast, often looks first to government to solve societal problems without considering other options.”54 The budget for the Department of Education, for example, rose from $38 billion in 2001 to $68 billion in 2008.55 For Buchanan, Bartlett, and millions of other conservatives, Bush and the neoconservatives have hijacked Reagan’s vision for America by increasing government spending, whether it be for the war in Iraq or for other entitlements. Paleoconservatives seek a return to the “real” conservatism of Reagan, the conservatism of limited government. Reagan preached limited government, but his pseudo-disciples have ignored this by increasing education spending, as, for example, the No Child Left Behind Act. This program has given billions of dollars to the Department of Education in an effort to set national teaching standards as well as provide tutoring for poor children, but the Department of Education was barely necessary for Reagan. Whereas Reagan sought to curb the influence of government programs, Bush expanded their role, making them an active force in American life through the No Child Left Behind Act. Reagan explicitly said education should be left to the states, not the federal government. By the time the act was signed, Reagan could no longer comment on political issues, but his son Michael lambasted NCLB in his work The New Reagan Revolution, declaring, “Bottom line: No Child Left Behind is a centrally planned, Big Government invasion of the private rights of educators and parents.”56 Even the National Endowment for the Arts was enlarged. Bush was a false prophet. The revolution was betrayed.

Yet Bush wasn’t always about Big Government. When he vetoed a bill that would have provided health insurance for children who were too wealthy for Medicare but didn’t have private insurance, Democrats were outraged. “The president and Republicans in Congress say that we can’t afford this bill, but where were the fiscal conservatives when the president demanded hundreds of billions of dollars for the war in Iraq?” asked Representative Jan Schakowsky (D-IL).57 The answer is simple: one expands freedom, the other restricts it. If successful, the war in Iraq would bring free speech, freedom of the press, freedom of religion, free elections, and free trade to Iraq. The war in Iraq spread the Kingdom of Freedom. Expanding government-run health insurance only stretches the reaches of government, restricting freedom. The billions of dollars that would be needed to pay for expanded health care would come from the American taxpayer. “I believe in private medicine, not the federal government running the health care system,” stated Bush.58 We must vest our faith in the free, private sector. There are no inconsistencies. Freedom is the highest concept, the greatest value, which transcends all other values.

Although they are never linked, understanding Reagan’s and Bush’s positions on the universal applicability of American values can explain another controversial position as well: the 1986 Amnesty Act. If we view Reagan as a man committed to bringing the Kingdom of Freedom to everyone, his highly controversial position about immigration becomes more rational. Reagan attempted to allow non-Americans to experience the American dream and freedom. Reagan and Bush both rejected hardline conservative ideas about illegal immigration. Whereas some (if not most) conservatives seek to expel illegal immigrants, Reagan and Bush embraced more liberal immigration policies, opening the door to American freedom to several million illegal immigrants. If there is one issue that frustrates conservatives about the Reagan presidency, it’s this one. The Immigration and Reform Control Act of 1986 granted amnesty for undocumented workers who arrived in the United States prior to 1982. Edwin Meese, Reagan’s attorney general, opined, “The lesson from the 1986 experience is that such an amnesty did not solve the problem. There was extensive document fraud, and the number of people applying for amnesty far exceeded projections.”59 A conservative criticizing Reagan? Blasphemy. But Reagan’s and Bush’s liberal amnesty policies come from their desire to extend freedom to people who hitherto had been denied such privileges, because by liberalizing our immigration laws, we further open the doors to the Kingdom of Freedom. This is consistent with their ecumenical principles. Freedom should be open to everyone, regardless of the material consequences. As Cannon put it, “Reagan was a democratic internationalist. He believed that those who did not live in America were equally entitled to the blessings of freedom and material prosperity.”60 The Kingdom of Freedom is meant for everyone.

Bush and the neoconservatives have learned the lessons of history from the Reagan years when it comes to budget deficits. In Reagan’s case, the budget deficits had minimal economic impact. Reagan and Roosevelt were the two biggest deficit builders in American history, but their budget-deficit-ridden eras were economically more prosperous than the preceding eras. Both of them justified huge deficits as a means to improve the economy and fight war. Both succeeded. And despite the deficits they left their successors, the ensuing eras of the 1950s and 1990s were some of the most prosperous in American history, certainly more prosperous than the eras that preceded theirs when deficits were smaller.

This may be called an unintended consequence of the Reagan presidency. Before his presidency he was a deficit hawk. In fact before becoming president, Reagan worried about budget deficits nearly as much as he did about Soviet communism and government intervention in the economy. He lamented in 1964, “Our government continues to spend $17 million a day more than the government takes in. We haven’t balanced our budget 28 out of the last 34 years. We have raised our debt limit three times in the last twelve months, and now our national debt is one and a half times bigger than all the combined debts of all the nations in the world.”61 Yet today conservatives accept the mass budget deficits of the Bush administration. Whereas pre-Reagan Republicans were deficit hawks, post-Reagan neoconservatives are deficit defenders.

Second Democratic Interlude: Barack Obama

I think Ronald Reagan changed the trajectory of America in a way that Richard Nixon did not and in a way that Bill Clinton did not. He put us on a fundamentally different path because the country was ready for it.

—Barack Obama

Reagan and Obama were thrust into office due to an economic crisis and arguably low points in American history.62 Both saw plunges in GDP growth and declining job creation in the midst of their election. The American people sought change and renewal. Reagan and Obama promised this. Who had it worse upon entering office? That depends on which stats you emphasize. Unemployment was roughly the same when both men entered office. It rose to roughly 10 percent by the second years of their presidencies, then began to slide. In fact graphing unemployment shows remarkable similarities. Of course, Obama inherited a housing and credit crisis, which Reagan did not. The collapse of the housing market in 2008 had ripple effects across the world. Record foreclosures meant losses for the banks, which were passed on to those seeking credit, dramatically slowing the flow of money in the American economy. But soaring interest rates meant that money was stagnant when Reagan took office. They soared to 20 percent in 1981. And Reagan had to deal with double-digit inflation, which Obama did not. In 1980, when Reagan was elected, inflation was a staggering 13.5 percent. In 2008 it was a modest 4 percent.

In most respects the economy that Obama left us is better than the one he inherited. Conservatives counter that the Obama recovery has been the worst recovery from recession in modern times. Despite the fact that America has been out of recession since 2010, economic growth has averaged roughly 2 percent. To put this number in perspective, Obama is the first modern president to have zero years with at least 3 percent economic growth. Even George H. W. Bush and Jimmy Carter, neither renowned for the economic prosperities of their eras, had multiple years of 3 percent growth, in four-year presidencies. Whereas the American economy expanded at roughly a 2 percent rate under Obama, it surged under Reagan at an average of over 4 percent. This helps explain why middle-class Americans were more frustrated after eight years of Obama than after eight years of Reagan.

GDP matters more than any other statistic because it measures the wealth of an economy. Recessions are defined by a shrinking GDP; they have nothing to do with unemployment and job creation. Citizens in nations with high GDP have higher wages and incomes. This means they have access to more tax revenue, meaning more money for schools, teachers, health care, the social safety net, infrastructure, and military. Imagine two societies, each with equal populations, each taxing their citizens at a 20 percent rate. One has a $10 trillion GDP, the other $5 trillion. The former will collect $2 trillion in tax revenue; the other, $1 trillion. Even if the former has higher unemployment, it can afford to pay its unemployed workers more in unemployment insurance, for example. Unemployed Americans make more money than employed people in many parts of world. During the most recent recession, an American concept called “fun-employed” emerged. Why can unemployed Americans have so much fun? Because America has the highest GDP in the world.