He found a job at the original Pottery Barn on Tenth Avenue in Chelsea—then really a barn, actually selling pottery. When co-worker Wendy Wolosoff-Hayes met him, he was still David Voyna. She invited him over for dinner, and in the sketchbook where she was collecting recipes, he drew a bare-breasted woman—one hand holding a breast while her other hand touches a long-eared rabbit. He labeled it “David’s first porno drawing 1973.”

David worked in the basement with the discounted items, but his main job was packing bags and loading them onto a dumbwaiter. Working with him was a young writer named John Ensslin, who eventually became David’s best friend and co-editor of the literary magazine they started: RedM. By the time they met, David had taken back the surname “Wojnarowicz.” (The change to “Voyna” was never official.) Ensslin described his new friend as a voracious self-directed reader. The two of them spent hours in the Pottery Barn basement discussing poetry.

In this era, poetry was braided into the counterculture. Every coffeehouse and bar boasted a reading series, or so it seemed, while small presses and little magazines proliferated. When David came off the streets and returned to school, he’d discovered Rimbaud, Kerouac, and Genet. While he still drew constantly, he hadn’t gone past quirky line drawings, occasionally funny, sometimes tentative, often derivative. He hadn’t yet found a way to connect his art to what moved him. But with poetry, he’d discovered a path quivering with hallucination, euphoria, dissociation, and rage—the hot spots on his own internal map. And the legends must have resonated too: Rimbaud leaving Charleville, wandering beneath the stars in torn clothes, sleeping in a Paris doorway, getting arrested and sent home as a vagrant. Kerouac hitting the road with Neal, rhapsodizing over diner food, conversing with bums. David romanticized that life. Certainly he saw it as a model for how to think about his own experience.

By late ’73 or early ’74, David had left town to live on a farm outside Churubusco, New York, near Plattsburgh and just a few miles south of the Canadian border. Exactly how David came to be living with a couple named Paul and Jane Braun remains a mystery, but apparently he knew both Paul’s father and brother from Pottery Barn.

Among his contact sheets are three—in an envelope he labeled “FIRST PHOTOS (AWFUL)”—that come from this location: a hippie couple, a dwelling that looks like two connected yurts, a haymow, a potbelly stove, snow-covered farmland, and young, long-haired David. What appears to be his first letter to Ensslin from Churubusco is postmarked February 23, 1974. He reports that he’s practicing the harmonica and will soon help someone build a fieldstone fireplace. In subsequent letters, David mentions planting a half-acre garden, building compost bins, and tearing down an old house “for lumber to build the barn.”

He and Ensslin were also exchanging poems in the mail. Responding to one critique Ensslin does not recall making, David wrote, “I understand what you are saying about my poetry as far as its bordering on self pity.” In another letter, he says he is “trying to refrain from being hung up on depressing things as all I’ve been writing is about some sad gray dismal thing in life.… people wandering in the great grey void of the world, endless littered streets, sagging docks and railroad cars rusting in the oily rain.… I can’t change what I write about or rather feel so it’s a never ending cycle which really throws me around.” He hopes to do primal scream therapy “so as to work out the tension.” And he wants to take writing classes, “as I need them terribly.”

Ensslin lived in North Bergen, New Jersey, and organized poetry readings in nearby Weehawken for an antiwar, pro-farmworker co-op called the Community Store. He also edited its mimeographed magazine, Novae Res (New Things), filled with poets who’d read at the store. Though David had never read there—or anywhere—Ensslin invited him to contribute. The one and only issue appeared in April 1974, with David’s first published work: several illustrations, including the cover, and four untitled poems. “Running through the dense underbrush / twigs snapping angrily scattering rabbits / quail and others I fought my enemies / treading softly among the moss and ferns / stumbling over logs I waylaid my father.…”

John Ensslin, co-editor of RedM, hosting a poetry reading at Morning Star Arts Center, where he got David his first reading. (Courtesy of John Ensslin)

The other three poems include imagery of farm life, a dream that he and a girl are “enveloped in each other’s feelings,” and a childhood memory of ice-skating on a pond. For the cover, David created a careful pen-and-ink drawing of the Sea-Port Diner in Lower Manhattan. Inside he illustrated some of the other poems—here a caterpillar on a branch, there a hand lifting a child’s drawing from a garbage can. He hadn’t found his style.

In a letter postmarked April 23, 1974, he asked Ensslin to send copies of Novae Res to his sister’s house in Queens because he was leaving Churubusco for a while. Obsessed with going to California, David had come up with a mad plan. Later, his claim that he tried to ride a bicycle to California and made it as far as Ohio would seem especially unbelievable. But he really did this. (He just, typically, had the date wrong.) That spring, he returned to his sister’s place in Forest Hills to prepare. Somehow David had acquired a nineteenth-century edition of the complete works of Shakespeare, which he sold for two hundred dollars—to Fitzgerald, who wasn’t sure they were worth that much. But this allowed David to buy a bicycle.

Fitzgerald recalled the day David left for the West Coast. “Pat and I went out to bid him farewell, out in front of the house in Forest Hills. He got on his bicycle with a knapsack on his back and started wobbling up the block, and I said to Pat, ‘He’s not going to make it to the Brooklyn Bridge. He’s just ridiculous.’ And she goes, ‘You’re always putting him down,’ and I said, ‘Pat I’m not putting him down. I’m realistic.’ “

They did not hear from David for two weeks. Finally he called collect—from Ohio. He’d been sleeping on the ground and someone had stolen his wallet, leaving him flat broke. He was also very sick. Pat and Bob wired him money, telling him to ship the bicycle and take a bus back to New York. Fitzgerald recalled David going into the hospital with pneumonia upon his return. Then he went back to Churubusco. In an undated letter to Ensslin he reported, “I am doing a lot better after abandoning my insane cross-country trek to primal therapy.”

The sojourn upstate is most notable for David’s changing perspective on it over the years. In a letter to a friend written in 1976, he described his time there this way: “I did an acre of organic vegetables and an acre of grass in the backwoods in a clearing.… The people who owned the property were almost never there it seemed & I had no vehicle other than my own legs so I spent weeks wandering through the woods & streams & sitting in a rocker in one of two domes we built burning cherry wood and letting the mind wander out into the dusty fields.” But when he constructed his Dateline in 1989, he wrote: “Worked as a farmer on Canadian border. Was supposed to share profit from ten acre vegetable garden. When time to pick crop, the vet tried to run me down in a pick-up truck. Left for n.y.c.” Both accounts could be true: An idyll that ended badly. But it’s like hearing from two different Davids and it’s right there in the syntax—from breezy long lines to telegraph staccato.

David returned to the city by late August 1974. In September, Pat left for Europe—a move she never expected to become permanent. She had signed with the Stewart Modeling Agency sometime in ’73, and the agents there decided she should go to Europe “to build her book.” Within a year, she was on the cover of L’Officiel. She appeared in a Vitalis commercial that ran during the Super Bowl. Her modeling career would continue until 1986.

Steven had left New York City in ’71, after taking an extra six months to graduate from high school. (He too had had excessive absence.) “I had turned my life around in the Home,” he said. “I started to understand conceptually how you can get ahead if you just cooperate. And so I was given an honor from St. Vincent’s for being an excellent child and student, and consequently they agreed to pay all of my college tuition.” St. Vincent’s also gave him money for rent and, when he was ill, paid his medical bills. Steven began his studies at Middlesex County College in Edison, New Jersey, about fifteen miles from his father’s place in Spotswood. He began trying to reconnect. He’d go see his father at five in the morning. “It was the only time he was sober. He would take me to the bar at seven, and he and Tuna Fish Charlie would have five or six shots of Seagram’s. Then I’d take off and leave him be.”

David and Pat visited their father once after Pat’s marriage. She wanted him to meet Bob Fitzgerald. Pat and David hadn’t seen the house in Spotswood before. What stayed with Pat is that her father wanted to show her the upstairs. “As I started to walk up the steps, he smacked my behind. I had a short skirt on. So I turned around and he said, ‘Oh come on. I changed your diaper when you were a baby.’ And I said, fuck this, and never went back. Couldn’t go back.”

As Fitzgerald remembered it, Ed had been friendly, nice, doting, giving them food. When Pat announced as soon as they left that she would never go back, he didn’t know why. As for David’s experience of the visit, Fitzgerald said, “I can picture him right now. He sits in this chair with this long hair. He had very long hair. Way down past his shoulders. With glasses. And he sat there and said nothing. Sat there and listened all day.”

Sometime in 1974, David visited Steven in New Jersey and drew some pictures for him. They would not really spend time together again for ten years.

After his sister left for Europe, David moved in again with Bob Fitzgerald in Forest Hills and got a job in Manhattan at Barnes and Noble, where he met poet Laura Glenn. There was a flirtation, “a little bit of a romantic entanglement that we had just briefly,” as Glenn put it. But David scared her with his stories about living on the street. “There was a seamy side to his life.” She also thought he was gay. David told her he was not. Ultimately, they were “just friends,” but there’d been a spark. When Glenn left for a job at Marloff Books on Sheridan Square, David would visit her there.

He soon left Barnes and Noble himself for a job at Bookmasters, a chain with several stores in Manhattan. There he hit if off immediately with a coworker, Peeka Trenkle, who was living with her boyfriend in a large apartment at 104th and West End. David had moved in with them by January 1975.

David lived at the West End apartment for at least a year and a half. Peeka’s boyfriend, Lenny, was a part-time musician and full-time purveyor of Thai stick. He had a music room lined with cork, a living room covered with red felt, a cat named Spider, and three extra bedrooms to rent out. David had a mattress on the floor, a pile of books, a Patti Smith poster, and a manual typewriter, at which he worked diligently on poems and stories. He sported a droopy mustache and hair down to his collar. The roommates took to calling him “Woj-narrow-witz” and recalled that, despite his shyness, he could be cuttingly funny, and though he wanted to be a writer, he also did a lot of drawing. “That was almost compulsive,” Peeka said.

On January 31, David gave his first public reading at Morning Star Arts Center in Union City, New Jersey, thanks to Ensslin, who organized it and acted as MC. The next day, David wrote a rapturous three-page letter to Ensslin, though by then Ensslin was ensconced nearby, in a Columbia University dorm. “Oh joy,” David began. He’d been so nervous, so keyed up, he wrote. “But when you gave that introduction, it bang-knocked away all fears inside.” A world had opened and David was feeling expansive. So, if the Community Store in Weehawken needed anything—a political cartoon for the newsletter, a painting to sell (the co-op could keep all the money), any resources he had—he would give it. He wrote that he was again anxious to travel but said, “I get this vision that I’ll lose all I’m hoping to do if I leave now. Just starting to get slowly in touch with work (writing) and I have so far to go before I can successfully release my unspeakable images, visions, whatever. I’m glad having friends like you.… Maybe it’s all inside me and it takes certain people to strike a thing inside that releases it all or in parts.”

Ensslin was dating a woman named Lee Adler, who lived on Court Street in Brooklyn with two young gay poets, Dennis DeForge and Michael Morais. Ensslin had invited DeForge and Morais to read in Union City along with David. Though David doesn’t mention them in his letter to Ensslin, this had been a significant encounter. The poets at West End began to socialize with the poets on Court Street. Morais was editing Brooklyn College’s undergraduate literary magazine, riverrun, and David drew the cover and an illustration for it that year.

He also had an affair with Morais, much to the surprise of everyone who heard about it later, including DeForge, who did not think David was gay. David was not even sure he was gay at this point. He kept the relationship secret, but Morais told DeForge about it. People who knew Morais seemed to be in awe, describing him as not just a dynamic performer of his own poetry but also “a muse” and “creativity personified.” He’d been part of the Negro Ensemble Company. He was also bisexual. Within a year or two, Morais had married and moved to Montreal, where David kept in touch with him by letter.

The West End apartment was convivial most of the time, with occasional agitation—and there David stepped in. Lenny, thirty-eight years old to Peeka’s nineteen, was constantly criticizing and browbeating her. David would sneak up behind Lenny, mimicking all the huffing and puffing, making faces. One night, a roommate named Leo—a black belt in kung fu—tried to break down the bathroom door so he could beat his wife, who’d taken cover there, and David stopped him.

On Easter they were all sitting around, too broke to do anything festive, when David caught one of the cockroaches that infested the place, cut out bunny ears, gave it a cotton tail, and set it down on the kitchen table, where it lurched along in its costume to the delight of the roommates. Years later, David would name these critters “cock-a-bunnies.”

He spent hours in the kitchen talking to Peeka. She was the one he spoke to about his father’s violence, perhaps because she too had had a rough childhood. Her memories of these conversations were vague, but she recalled their “heart connection,” that David was troubled, that they talked at length about painful things, and that he would cry. She felt there was a softheartedness in him that he was not interested in cultivating. After he moved out, in 1976, they lost touch. “He was very enamored of William Burroughs and Jack Kerouac and this sort of self-destructive brilliance—he loved that and we used to have talks about it,” Peeka said. “My big question was, do we have to destroy ourselves in order to be creative. I felt like he was kind of hell-bent on it. He wanted that. He wanted the dark part.”

Peeka Trenkle became a confidant of David’s while they were roommates at the West End apartment. (Courtesy of Peeka Trenkle)

By early ’75, David was working at the Bookmasters in Times Square. Sometime during that year, he ran into his old high school pal John Hall—either at Bookmasters or on the street. They hadn’t seen each other since David was fifteen and they’d squabbled over something. John Hall couldn’t get over how much better David looked. Aviator glasses instead of “goofy” glasses. A decent haircut. “I remember thinking pleasantly … he looks more normal now, whatever that means.”

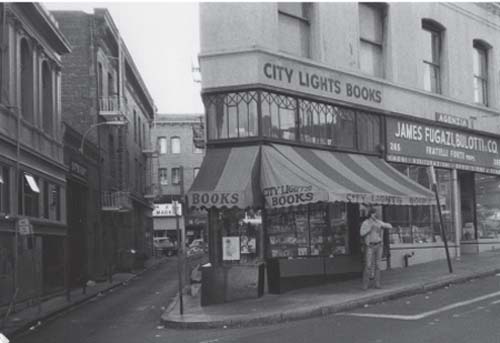

Late in the summer of ’75, David went on vacation and finally made it to California, the first of many cross-country trips. This time, he took the bus. First stop: San Francisco, where he made the neo-Beat’s pilgrimage to City Lights Bookstore. “A three floor rush,” he reported via postcard to Richard Benz, another poet and a colleague at Bookmasters. He dipped into Mexico, which he found difficult—“as I know little Espagnol (?)”—and spent his twenty-first birthday at a religious youth hostel in New Mexico.

He wrote prose poems about both the Nashville and Denver bus stations, along with a short story set in the El Paso terminal. All those bus stations. If he wasn’t yet ready to write about his own experience, the transients and lowlifes often found in such spaces, especially in the seventies, would do nicely. David identified with street people and outcasts right to the end. “Every stinking bum should wear a crown,” reads one of the epigraphs to his book Close to the Knives.

In 1975, David took the bus to San Francisco and made his first pilgrimage to City Lights Bookstore where he asked someone to photograph him. (David Wojnarowicz Papers, Fales Library, NYU)

By the time David returned, Ensslin had taken a room at the West End apartment. Earlier that year, Peeka’s sister Sauna had moved in. She was just seventeen or eighteen but soon found herself going to readings with David and Ensslin, immersed in their ongoing raptures and debates over poetry.

Bob Fitzgerald also accompanied David to readings occasionally. Fitzgerald described David’s poems as “letters” because they didn’t rhyme. “He was very introverted,” Fitzgerald said. “Until he got up on those little stages and he started reading his letters, wailing about something that was bothering him in society. He’d go to these sleazy little coffee shops and there’d be about eight readers. He could stand up in front of a crowd, which always amazed me, because he was so shy.”

That fall, David signed up for Bill Zavatsky’s free workshop at St. Mark’s Poetry Project. The class met one night a week from September to May and constituted the whole of David’s higher education. Zavatsky remembered him—a beanpole, very gentle, very soft-spoken. “You kind of had to pry stuff out of him.” David’s work from this period could be dense if not overwritten and purplish. Zavatasky would tell him, “Cut back, cut back, find a spine here somewhere.” But he encouraged David because he worked so hard, while some in the class produced very little. Zavatsky advised his students to do readings, do magazines, proliferate. At some point during this workshop year, David decided he’d start a journal—with Ensslin, who was not part of the class.

Eileen Myles was. She, of course, developed into a well-regarded poet, novelist, and critic. But she and David didn’t get acquainted until the East Village years, the 1980s. In Zavatsky’s class, she said, “We were not interested in each other.” She thought him passive, laid-back, and she didn’t remember his poems. In retrospect, she felt he’d used poetry as a launching pad. “Part of the reason poetry gets sneered at as a form so often is because it’s where so many people began,” she says. “Poetry is very often a plan. Like a list. At the beginning of a career, it can be a list of the directions you’d like to go.”

David brought Richard Benz, his buddy from Bookmasters, into Zavatsky’s class, and Benz recruited four poet friends from Staten Island. David then invited the Staten Island poets to contribute to his magazine, but not Eileen Myles. One of those Staten Islanders, Richard Bandanza, recalled that David also got him some poetry gigs. Ensslin set up readings at West End Café, and David often suggested people to him.

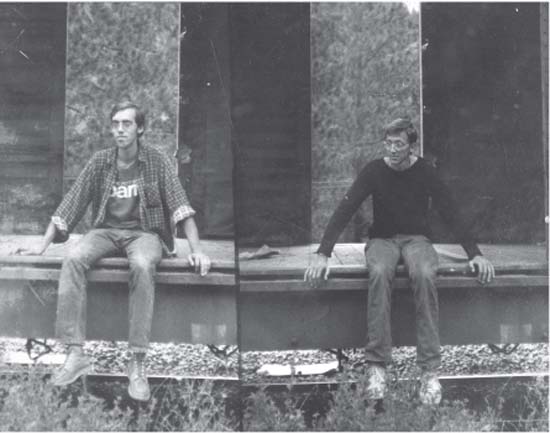

Around the time he started at the Poetry Project in the autumn of 1975, David began a love affair with Jezebel Cook, who was sixteen and Sauna Trenkle’s best friend. Jezebel had dropped out of school and left home, and she liked to go to Sauna’s and hang out with the bohos. “He actually pursued me and had this crush on me,” Jezebel said, “and I remember him bringing me a ring back from Mexico.” She’d just left another boyfriend, a “crazy, sick, nutty relationship.” She moved in with David. “I’m not really sure why it didn’t work out. I was very kind of hurt by not understanding. Seemed like I was madly in love with him, although I remember in the beginning it was the other way around.” The affair lasted for a few months. Jezebel is certain that it was over before she turned seventeen, in February 1976.

David with his girlfriend Jezebel, probably late in 1975. (Courtesy of Peeka Trenkle)

A decade or so later, David was long out of touch with his friends from West End and the Poetry Project, but as he became a public figure and spoke about his background, the old friends were stunned to hear the stories. Each brought up doubts when I spoke to them, even Peeka, one of the few to hear the stories from David directly. Throughout his life, David selected certain people to hear certain things and kept people he knew apart from each other, which Peeka understood. “It’s what the psyche needs to do when there’s been a lot of trauma. There’s no way to have a continuous linear reality. You have to compartmentalize. Otherwise it can flood your consciousness.” He had told Ensslin and Peeka about his hustling years. He’d talked to Peeka about his abusive father. But she found it hard to put his stories together with the David she knew. Even as she heard the anecdotes, she sometimes wondered “where it was reality and where it was elaborated on and where it was fictional.”

When Richard Benz heard about David’s past, he discussed it with others who’d known him. “Hearing some of the backstory about him being on the street, the piers—we were just saying to each other, when did this happen? Because he wasn’t doing that when we knew him, and he didn’t seem to be that kind of person. That sounds terrible, but it didn’t seem like he had come out of that life.” This was actually a general consensus. As Richard Bandanza put it, “Drama was absent from my recollection of this guy. A lot of people felt—wow, this is very counter the kind of guy he seemed to be. In the poetry scene, there was speculation that he sort of made it up—some of it.”

None of them had known he was gay. Eileen Myles, who wasn’t yet out herself in 1975, said that the David who came to Poetry Project “looked like a straight guy with a lot of hair.”

His ex-girlfriend Jezebel said, “That he was gay was weird to us because we had no idea. When we knew him, that wasn’t part of his story.” And she wondered why he hadn’t talked to her about it. She was not judgmental. “I have become a social worker because I’m the kind of person people tell all that shit to. I just find it odd that I wouldn’t know anything about that.” But it was how David handled his conflicted feelings. He just didn’t bring those feelings to the surface. Jezebel didn’t know what to think about the idea that he’d had a terrible childhood. “My impression is that some of that is how he invented himself.”

Certainly, his letters from this period indicate that he’d honed a cheery affect.

David was hiding, maybe even from himself during the poetry years. But part of him would always wear camouflage. No one who ever knew him—not even those closest to him—saw all of David.

Sauna Trenkle was most surprised to learn that he’d become an activist. She’d always had the impression that “he felt he had to keep a low profile.” She also used to notice him crying over “things you wouldn’t assume someone would cry about.” Like some poignant moment on a television show or “a beautiful meal with people all being nice to each other.” He and Sauna talked about “how overwhelming the good things could be,” she said. “Because neither of us had had a lot of good stuff happening in our lives.” Even with these sisters, he compartmentalized. Sauna knew nothing of his emotional talks with Peeka. And Ensslin knew nothing of the crying, but said, “There were times he would just retreat to his room and you knew to leave him alone.”

On November 29, 1975, David wrote to his sister Pat. “I really want to show you what I’ve been heading towards in my life,” he explained. So he composed a manifesto, a first articulation of his resistance to what he would later call “the pre-invented world.”

He wanted to explain his “feelings on the voice within the body, the voice of the subconscious.” While he had to follow this voice, or be unhappy, he knew that it would take “a separation from the normal levels of existence,” a rejection of “the foundation that really covers over the real world underneath.… The reasons for my wanting to reach this level … is to find the entirety of my own soul … to find that area in the vast cosmos both internally and externally where the true voice is to be found. Rimbaud came close to it, he came so close but turned his back to it on its very steps, either out of fright from what he saw or because he was unprepared to meet it.… I am a poet, one who hasn’t found the true voice yet.… I won’t worry about total acceptance once I break through the immediate binds around me which hold me back. What is really more important is that I at least give my life up to it.”

He did not mail this letter.

In December 1975, Lee Adler was murdered in the Manhattan neighborhood of Washington Heights. Though she and Ensslin had split up by spring of that year, he was still quite traumatized and remembered what a good friend David was to him then, talking to him about it, not letting him isolate. Police never figured out who killed Adler. She was one of 1,631 homicide victims in New York City that year.

David had begun to work, with Ensslin, on the journal they would eventually title RedM—and dedicate to the memory of Lee Adler. The title stood for “red mirage,” or as David used to say, “Red M I Rage.” Ensslin explained: “It had to do with this thing David talked about. There’s what you see in front of you and then there’s this movie that plays in your head, this internal vision that you have of what’s going on around you. He used to call it ‘the film behind the eyeball.’ That was his expression. So the magazine, if it had any kind of collective reason for being—it was a celebration of people’s individual visions.”

By 1976, David was making some headway with his poetry connections. Peter Cherches had taken over as editor at riverrun, and he accepted a poem along with two of David’s photographs: a winter woodland scene and an old man alone in a coffee shop. Zavatsky’s class did a xeroxed zine, Life Without Parole, which included two poems by David, one on the Nashville bus station. But the big coup was getting a poem accepted by Cold-spring Journal. Not only did the other contributors include Aram Saroyan and Gerald Stern, but one of the editors was Charles Plymell, a poet who’d lived with Neal Cassady for a while and counted all the Beats as friends. Coldspring no. 10 included David’s prose poem on the Denver bus station (“7 blocks from station / the sidewalk in fronta liquor store filled w/great assortment of bums old/young all w/the same looka shock in their eyes / standing/leaning w/taut bristled faces”).

On February 22, David went with John Hall to hear Plymell read at the Fugue Saloon. Plymell called in sick, but the other reader that afternoon inspired David to write a fan letter. That poet was Janine Pommy Vega, younger than the other Beats but also part of their scene. She didn’t reply to that letter, but David wrote to her again in May, asking her to contribute to his then-unnamed magazine. He had decided to just write blind to poets he admired. He even tracked down Carl Solomon, the man who’d inspired Allen Ginsberg to write “Howl.” David found Solomon working in the appliance department at Korvette’s. In the end, RedM included Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Bernadette Mayer, Ron Padgettt, Charles Bernstein, Plymell, Solomon, and Pommy Vega along with friends like Benz and Bandanza, De-Forge and Morais. While they had no trouble drawing contributors, David and Ensslin hadn’t realized how much labor would be involved. Producing RedM would take more than a year. They published only one issue.

Among David’s papers, I found answers to a questionnaire about his poetry life. “I have plenty of interests besides writing but I devote no time at all towards them,” he reported. “I gave up the application of paint to paper some time ago because I found writing a much more effective release for me.” Prompted to say where he’d published, he omitted Novae Res but listed the other publications above, along with Zone (where his work appeared in 1977). That was the extent of his poetry career.

And once he began to tell his own story, David erased it all. Even the people closest to him at the end of his life knew nothing about RedM or Forest Hills or Pottery Barn. Fales Library at New York University ended up with 175 boxes of material. Along with his diaries, correspondence, and photos, the collection includes torn to-do lists, envelopes with footprints on them, wads of ATM receipts—but not a single one of the literary magazines that published David’s poetry except for one copy of his beloved RedM.

The poetry in particular seems an odd thing to hide. Maybe David regarded his poetic output as juvenilia he couldn’t be proud of. Maybe it was just too much the conventional path into the artist’s, or certainly the writer’s, life and didn’t suit the persona he’d crafted. Certain friends of David’s from the mid-seventies came to feel that this was about more than creating a persona, however—that David had willed himself into becoming someone else.

David yearned to hit the road, and later in his life he would speak of his many hitchhiking and freight-hopping trips across America. He certainly hitched to Montreal and back at least once to visit Michael Morais. But he made just one round-trip to the West Coast and back that way, with very little freight-hopping, in summer 1976.

He intended to head, once again, for the holy grail of City Lights Bookstore, this time with his tall, skinny buddy, John Hall. They studied The Hitchhiker’s Field Manual, with its state-by-state suggestions about where it was safe to thumb a ride, and they found Michael Mathers’ photo book Riding the Rails a great inspiration. Hall said they knew they wouldn’t be able to hop a train until they were away from the eastern seaboard. Not that it couldn’t be done. But it was “like secret hobo knowledge and more advanced than we were capable of.”

David had hoped to finish production work on RedM before he left town. But a friend who was going to surreptitiously typeset the poems at his shop had been too busy to do more than one a week. Ensslin had left Columbia, broke, and gone up to the Berkshires to work for the summer. Early in June, David wrote him to say they’d have to do most of it on an IBM Selectric at the Print Center in Brooklyn. David used vacation days from the bookstore to type. In another letter to Ensslin he said he’d found an image for the cover in the twenty-five-cent bin at Argosy Books—a geological survey plate showing a cave town cut into a cliff, and a man in a cowboy hat seated on the cliff edge. This “gaucho,” as David described him in a letter to Janine Pommy Vega, was staring in a trancelike way, “like someone who has seen behind the eyes for the first time.” At that point, RedM went into limbo. The nonprofit Print Center had shut down till October for lack of funds.

On July 15, 1976, David left town with John Hall and Peeka Trenkle, who drove them to Massachusetts in a borrowed VW bus. They wanted to visit Ensslin before the hitching began. For the first time since his Outward Bound trip, David would keep a journal, and he waxed Kerouacian as he recorded day one: “into dense sound of all of America rushing forward—destinations—shaved forests—lonely tollbooth guards with empty holsters—all the country moving … crossing state lines into areas unknown myself now homeless (no base place) makes me feel that disconnectedness.”

Ensslin had rented a room in West Stockbridge from Rosemarie Beenk, a former Isadora Duncan dancer then in her midsixties. David was entranced by Rosemarie, someone who had lived for her art. At her little house on the Williams River, he and John Hall spent a five-day idyll, swimming in a nearby marble quarry and hiking. They also created the first of their “Trail-o-Grams,” news on their travels that they would send to friends back home. David drew R. Crumb–style illustrations and they both wrote, though David wrote most.

While at Rosemarie’s, David also worked on a “story about brief time doing the streets,” the account in which he refers to Willy as Lipsy. “I no longer have any scars on myself in any sense of the word,” he wrote in an introductory paragraph. “Confronted by the past I take it as the present.… Regret hasn’t any meaning.”

On July 20, two hopeful hitchhikers bound for California left Rosemarie’s place near the western edge of Massachusetts carrying a sign that said “Syracuse.” After some initial good luck—a ride to Albany—their first twenty-four hours developed into an almost comical ordeal: the hours of waiting on an entrance ramp in the rain, the three other hitchers jumping ahead of them into the one car that stopped, the decision to then camp in a marsh infested with mosquitoes and potato bugs, the scramble back to the highway, the can of fruit cocktail split for dinner, and finally the ride near midnight to a rest stop east of Utica, where they slept behind a state police station in the rain and nearly got arrested in the morning.

They finally got to Syracuse on their second day, after someone dropped them a mile away and they walked. David went to the university library and read half of Kerouac’s Tristessa—a novel almost impossible to find in 1976—in the Rare Books Department.

Already David was collecting stories from people he encountered, some of them destined for his book Sounds in the Distance (reissued after his death as The Waterfront Journals). He never taped, just listened intently, and the storytellers I’ve been able to find vouch for his accuracy. At this point, however, he didn’t have publication in mind. The first “monologue” he’d recorded was Rosemarie Beenk’s warped account of the American Revolution—how it started when the king ordered people to drink tea instead of coffee. Then, as he moved across the country, David also wanted to hear, for example, from a guy he met who took his nephew rail-riding and who never looked for work until his money got below fifty dollars. David wanted stories from those who’d opted out of society, or had never gotten in—the footloose, the pariahs, those who did what they wanted, paid the price, and didn’t care. David treated these (usually) marginal people as if their positions on the margin gave them access to secret truths.

In Northfield, Minnesota, they stayed a couple of days with a friend of David’s, a poet he’d known in New York as a “burning Cassady character.” But now that energy was gone. The friend was a forklift operator. “He’d given up in a way I never thought he would,” David wrote to Ensslin, disquieted. While they were in Northfield, David and John Hall assembled their second and final Trail-o-Gram.

From here, the trip became arduous as they began trying to freight-hop. In St. Paul, they prowled the train yards, consulted hoboes for advice, snuck into open cars that would back up instead of move forward, and kept running into security guards. Then someone shot at them from a car full of kids, and David felt the bullet go through his hair. But later he wrote in his journal about what he considered the truly disturbing moment of that day—he’d gotten a haircut, thinking it would make travel easier. He assured himself, that, while his new image felt unnatural, he still saw through the same eyes. And if the people driving the cars or sitting at counters could see behind his eyes, he’d be in trouble.

After another bungling day or two at the rail yard, he and John Hall went back to hitching. In North Dakota, they waited twenty-four hours for a train they then rode for four hours. (They had to ditch when workers began searching the cars.) They were halfway through Montana before they had consistent success with rail-riding. Finally they put their hammocks up inside a freight car and rolled toward the coast. Nearly broke by the time they hit Portland, Oregon, they spent a day there in fruitless job hunting. David decided then that they better head for San Francisco, where he would “either find work or slowly fall into becoming a bum.”

David and John Hall on their cross-country trip. David joined the two separate photos, taping them onto a three-ring binder labeled “Journal New York–California 1976.” (David Wojnarowicz Papers, Fales Library, NYU)

They were able to freight-hop for one more night, until the train stopped just south of Mount Shasta and two officers of the law chased them away, brandishing clubs. That ended David’s rail-riding career. They hitched the rest of the way, arriving in San Francisco on August 12, only twenty-three miserable and exhilarating days since western Massachusetts.

John Hall took a bus back to New York after about a week. They’d moved into the San Francisco YMCA, where David remained as he started looking for a job. “Oh silent San Francisco with your long streets of movement yr New Yorkian times square with pomegranate nosed winos leafing through the trash where is your secret,” he wrote in his journal. “Do I stand a chance in your woeful streets?”

By his second week, he was heading out at six A.M. for the Casual Labor Office. There he found work sorting eggs for the V-C Egg Company. The Viet Cong Company, he liked to joke. His job was to sort by size, removing any that were cracked or misshapen, for $2.50 an hour. But his major work in San Francisco became the collection of stories and voices. At the Labor Office. At the Y. And every day during lunch at a Chinatown greasy spoon where he listened to the regulars—junkies and “dull gangsters”—and made notes on napkins. Later he included many of these stories in Sounds in the Distance.

David and Ensslin were corresponding about RedM, still adding and subtracting poems. “At this point have lost touch with old self” he informed Ensslin on September 7, but it was too much for longhand. He needed a typewriter “to explode on.” He hoped John Hall would send his soon. By September 9 he had a machine, and his explosion produced a seventeen-page, single-spaced epistle to Ensslin—“a letter I could only write to you and maybe John Hall,” he said. He was trying to explain his “attraction to extreme social outcasts.” He’d been talking night after night “till 1 2 3 4 am” to his next-door neighbor at the Y, a “strange Genet-ian character.” This man had checked in with the clothes on his back, one extra cotton shirt, The Tibetan Book of the Dead, and a pack of Pall Malls. He told David a long, complex tale about his “self-imposed hermitude in a boarded-up house in New Orleans”—which is part of the title David gave it in Sounds in the Distance. David thought he needed to associate with certain characters, like this man.

“One of my fantasies for a long time,” he wrote Ensslin, “had been to withdraw again into the streets away from the social mainstream of society and hang out again with every kind of social ‘monster’ and keep secret notebooks hidden beneath my coat … writing the grim sagas of that experience. But I don’t need that fantasy any longer. I no longer entertain it ’cause it’s inevitable—I’ll end up there. Whether in a few years, or more likely when I am an old man, toothless and benumbed.… Ah hell. The way in which I’m living reflects the end.”

He’d had a cushy situation in New York—an easy job, an apartment with good, energetic roommates, comfort, money, books—and he’d tossed it all. Now he had a tiny room, few friends, and twenty bucks to his name. But he was happier this way! “Why? Because I’m experiencing the more important things in my thought of life. I’m associating with people who interest me and it’s that strange unknown beauty that I touch when riding into a town for the first time, not knowing a single person. It’s an unexplainable excitement I feel when approaching unknown things.”

He related more of his neighbor’s saga, even some of the guy’s dreams. He quoted Genet, from A Thief’s Journal, the part where Genet takes money that belongs to a friend—money the friend desperately needs—and tears it up, then thinks better of it, pastes it back together, and buys himself a big meal. To “purify” himself, says Genet. To break his emotional bonds. David couldn’t remember all the conversations with the fellow next door, but he remembered the feelings: that the guy was purging himself of everything programmed into him by society. The Genet-ian character wondered why David wrote, assuring him that it was useless.

The night before David wrote this letter, he began to feel he was disintegrating inside. As he explained it to Ensslin, “I went too far into an area I was incapable of handling at this point.” The area where you let go of the constraining walls that fence in your thoughts. Where you lose your opinions and “thought molds.” Where you see each and every thing as nothing. Where time isn’t understandable and politics are useless. “It’s an almost total abandonment of social ties,” a place in society he’d discovered two years ago when he first read Rimbaud. That night in San Francisco he had “this weird sense of [his] death drawing near.” He felt there was someone in the room with him. He heard a voice like his sister’s whispering his name, then felt what seemed like a jolt of electricity into his head. At three in the morning, the next door neighbor banged and kicked his door till David opened up. The neighbor came in and asked angrily, you have to work and I woke you, so why are you so calm? David didn’t know. The man walked out. Then David too left his room. It was “as if it contained all the things that I dislike,” he wrote, “all emotional and disruptive energies that I’ve come in contact with inside of myself in the last so many years—that I had rid myself of during the last two years at west end avenue.” The Genet-ian character checked out the next day.

On October 23, after learning that Bookmasters would take him back, David set out to hitchhike back to New York. Again, he started with great luck, as someone gave him a ride to Reno in a single-engine Cherokee aircraft.

Out on the interstate, he was fixing his sign (“East I-80 New York”) when another hitchhiker showed up. They stood there for four hours—the other hitcher walking back some yards to snag the first ride. No fair, David thought. But he didn’t say anything. Finally a battered pickup pulled over and, sure enough, the other hitcher got into the cab with two guys. As the truck cruised by slowly, looking for a place to nose back into the interstate flow, the hitcher yelled at David: “We’re going to Denver.” David yelled, “Can I come?” The truck stopped and he climbed into the back.

He was headed into the most dangerous ride of his hitchhiking life. The teens who’d picked him up had stolen the truck, and they began stopping to rob what David described as “supermarkets.” The other hitchhiker joined right in as their accomplice. According to David’s account in the Dateline, the self-described outlaws showed him their shotguns and said they were going to kill him, and if the police tried to stop them at any point, they intended to shoot it out. The account David gave Janine Pommy Vega in a letter was less dramatic; he’d pared it down to a couple of sentences: The outlaws did two burglaries and a robbery and “one hung out all night in the back of the truck with me talking about going to Mars.”

Later, when David typed out the entire journal he kept on the trip west, he wrote what he labeled “an intro of sorts” for John Hall. Here he tried to explain why he had not tried to escape from these kids, because he had had a chance, and whatever the exact details, he did feel his life was in danger. “After I had accepted all foggy notions of death,” he told Hall, “and slipped into that quiet reflective stage where I would think of anything and it was savored slowly … all I can remember is wanting to get out of it alive enough so I could tell you the story.” The outlaws had entered one market with the other hitchhiker, leaving David alone in the truck with their two shotguns. He could have run. Yet he just sat there. “I had to live it through,” wrote David, “regardless of what it led to—oh gee! Adventure! That’s all it really is sometimes and that’s all that matters to me in a series of systems that attempt to quash that kind of rush. Sure I get afraid, but somewhere in the midst of the action of following through an experience, there comes a sense that’s incomparable to any other. Ah, that’s what I strive for.”

He wrote this up for Hall by way of thanking him. He might never have jumped into that first railroad car without his presence. “I believe that it takes a number of things (objects or people) to stimulate certain currents inherent in one’s own system.”

He spent at least twenty-four hours with the outlaws. In the Dateline, he wrote that, when they finally dropped him off on a dirt road, he assumed they were going to shoot him and he ran into the woods. Later, a woman and her daughter picked him up in another stolen vehicle. As he told Pommy Vega, the women ducked every time a cop came into view, “which made the car swerve.”

Into the back of his journal, David pasted a warning issued to him by the Indiana State Police on October 27, 1976, for hitchhiking.

Soon after returning to New York, David moved to Court Street in Brooklyn with the other poets—the other gay poets. David had a long talk with Ensslin at the end of a pier on the Hudson and told his friend that he thought he was gay. He also came out to Laura Glenn, but added that he’d give up men for her if she’d have him. She declined.

Poet Steve Lackow drove David and his belongings from the Upper West Side to Court Street in Lackow Sr.’s old Chrysler New Yorker. It was snowing, the car had bad brakes, and they cruised into Brooklyn on a controlled skid. Lackow moved into Court Street shortly afterward. He remembered a David who drew compulsively on anything available and who survived almost exclusively on cheese sandwiches. David, Lackow, and Dennis DeForge shared the typewriter always in place on the dining room table.

That autumn, David read at the Prospect Park band shell in a series sponsored by Mouth of the Dragon, the first gay male poetry magazine. Among the spectators was Brian Butterick. “As soon as I saw him read,” Brian said, “I was like, ‘Wow, I want to meet him.’ “ David soon realized that he’d read one of Brian’s poems in the window at Brentano’s bookstore in 1973—and loved it. That year, Brian had won second prize in the New York City high school poetry contest, earning the display of his poem. David was either living on the street or at the halfway house.

Shortly after he met David, Brian moved to Provincetown, Massachusetts. But he would return almost a year later and become one of the few people from this era to stay at least semi-connected to David for the rest of his life.

Steve Lackow met David in 1975 and felt certain that David hadn’t seen his mother in years.

Actually, David had had some contact with her. In a letter to his sister, Pat, dated February 21, 1976, he wrote, “Dolores has been pretty quiet, getting in touch now and then out of a sense of motherly duty, I guess.… She’s sort of coming into her own and leading a life in her interests. I feel happy about that and don’t mind at all not hearing from her ’cause that means she’s happy.” About a week later he wrote again and mentioned that Dolores was on vacation—though he’d only heard that from Bob Fitzgerald and didn’t know where she’d gone. Clearly, he and Dolores weren’t close, but she did make the list of people who got Trail-o-Grams that summer.

After David moved to Court Street, she apparently made more of an effort to connect. “She caught up with him on the phone and then she came on over one day,” Lackow remembered. The moment stayed with him because, as he put it, he “couldn’t help hating her guts.” Lackow had had such an emotional response to David’s stories about living on the street. None of the other friends remembered this reunion, but in the end, everyone from the Court Street era met Dolores—and liked her. No one from West End had ever met her and didn’t remember David ever talking about her.

“Dolores is probably the most guilt-ridden individual I ever met in my life,” said Lackow. “Totally filled with regret about her life, about what happened with her and David. She did everything she could to remake that relationship. At first I don’t think David was all that interested, but ultimately he really was won over to it, and responded in kind.” Dolores was charming, vivacious, almost “puppy-doggish” as she sought her son’s approval. “She won us over. Basically we were following David’s lead,” he said. “He bent over backwards. I don’t know where he found it within himself.”

Since age eleven, David had seen his father for just a few hours, the day he visited with Pat and Bob Fitzgerald. Now David was twenty-two, and even as he reconnected with his mother, Ed Wojnarowicz was in a state of serious self-inflicted decline.

Ed’s alcoholism had worsened after he sent his three oldest children away. He had also left the merchant marine, after working on ships that took cargo to Vietnam, so his family no longer had the respite of his weeks at sea. He found boiler room jobs at local factories and schools, but he was always fired for drinking. He lost his driver’s license three times for DUI, first for six months, then for two years, then for ten years. He bought himself a moped. But usually Marion had to drive him to work. When he had work.

Marion now took the brunt of his beatings, though his two youngest children also lived in a state of terror. What came through in Pete’s and Linda’s stories was their father’s constant childlike need for attention: Waking Pete one morning to tell him some interminable story and giving him a fat lip when he didn’t appear to be listening closely. Coming home one night when Marion, Pete, and Linda were in the middle of dinner and heaving a plate of spaghetti against the wall when they didn’t stop eating to listen to him. Picking up the family dog by the neck and threatening to kill it if he didn’t get a reaction.

Marion took to shutting herself in the bathroom when Ed’s rampages began. It was the only room with a good lock. She’d bring a book and sit in there until he gave up or passed out. “He had a hatchet, and you’d see the marks [on the lock],” Linda said. Pete began trying to intervene in the attacks on his mother when he was thirteen or fourteen. Linda, Pete, and Marion all testified against him in court at some point. The police were now regulars at the house.

When he was unemployed, he’d head for the bar as the kids headed to school. Coming home from school was always fraught for them. Sometimes he’d be sitting in the front yard with a baseball bat. They could always dodge him when he took a swing, or outrun him—he was so drunk. But usually, they’d keep going, past the house to hang out with friends in the neighborhood. “We would stay for hours and hope for him to pass out on the couch,” Linda said.

“We were petrified whenever he’d start fooling around with a gun,” Pete said. Ed kept his rifles in a locked cabinet: a .30-06 rifle, a shotgun, an M1 carbine (now banned as an assault weapon), a .22, a .32 Marlin, and a BB gun. He hunted, but also liked firing the guns at home “outside the door for no apparent reason,” said Pete. “Just to be angry.”

He fired a gun in the house only once that anyone knows of: three shots through the downstairs bathroom ceiling with his .32 Marlin. Marion swears she was sitting on the couch when this happened, though both Pete and Steven believed her to be in that bathroom. Linda was the only other person home at the time, but she was upstairs, thinking her dad had just shot her mother dead. The bullets tore through the upstairs bathroom and out the roof. That night, the police arrested Ed and confiscated his rifles.

Marion began to stand up to him after she joined Al-Anon. Ed hated this, of course. He’d take her keys away and lock her out of the house when she went to a meeting. But she persisted and had the kids join Alateen. “I wanted them to understand they weren’t the only kids going through what they were going through,” she said, fighting back tears. For years, Ed had had the habit of stopping the car at some bar and telling the family to wait for him while he went in and drank. Sometimes they’d sit out there for an hour. Then, one day Marion decided to just leave him there. She drove away.

For eight or ten years, Marion worked a minimum-wage job at a blouse factory, sorting the pieces cut from patterns. She had to, since Ed was drinking up his pension check. Marion knew he hid his Seagram’s in a tire in the garage, and she tried pouring it out, especially when there wasn’t enough money to replace it. But the bar always gave him credit.

One night he came at Marion with the baseball bat and chased her out of the house. She called the police, who hauled him off to jail again. Several times, the court ordered him into psychiatric institutions for rehab. He’d detox. He’d work the program. He’d be pleasant when the family came to visit. But once he returned home, Ed was never sober for more than a day.

In December 1976, there’d been much talk in the family about Pete getting his license and helping to chauffeur the still-unlicensed Ed. Steven came to the house to confront his father. He was worried about Pete, knowing from his own experience that Ed saw his growing sons as a challenge to his authority. Steven pushed his father up against a wall and said, “Do you realize what it is to be so fucking afraid of you? Do you know what you’ve done to your children? I’m not afraid of you anymore. But I love you.” Ed broke down crying. Steven urged him to get away from the family and straighten out his life.

Pete turned seventeen on December 21, and Steven drove him to the Department of Motor Vehicles to take his driving test. The next day, Pete was the first one home from school. Walking in from the breezeway, he could see straight down into the basement. And there he saw his father’s feet. Off the floor.

“I got a knife and I cut him down,” Pete said. “And when I cut him down, an exhale of air came out of his lungs. I tried to give him mouth-to-mouth. And realized he was gone. I’m looking at him thinking, ‘This can’t be. This is friggin’ surreal.’ And I sat down on the steps. I cried maybe ten seconds, and then I stopped. And as I sat there—this was the oddest thing that ever happened to me—but the weight of years and years of abuse, it lifted off my shoulders. An unbelievable feeling. You never know the burden that you’re carrying until it’s lifted, but someone just pulled it right off me. And I felt free. There’d be no more abuse. It was over.”

Pat happened to be back from Paris for the holidays. Bob Fitzgerald drove her and David to New Jersey for the funeral. Three or four times, David begged Fitzgerald to pull over and stop so he could throw up. Since these pit stops followed an already late start, they actually missed the church service and joined the rest of the family graveside. Ed had drinking buddies but few friends. The funeral home had had to hire pallbearers.

That year, David spent Christmas Eve with his sister, his brother-in-law, and his mother at the Hell’s Kitchen apartment. David had been very quiet, when he suddenly stood up and said, “I have an announcement to make.” They sat there waiting until he blurted, “I’m gay!” and ran out of the room crying.

“Dolores really got pissed off,” Fitzgerald remembered. Not about David being gay. She just thought he’d ruined Christmas.