“Coming back here after that time in Paris so many scenes I once embraced as a living movement now seem weary and burlesque, a step outta rhythm,” he wrote two weeks into his return, still adjusting to the new pace and timbre of his life. It wasn’t just what he’d added while in Paris, but what he’d subtracted: “the removal from media, hard street energies, manic violence … and tension.” He didn’t specify what he now found “vapid, harsh and useless,” only observed that there was “an energy here that destroys the most subtle responses in human nature.” That same day he made notes for a new piece called “Wounded Wild Boy.”

He pulled back into his shell. At least in what he recorded about his life. (The passage above is unusually ruminative.) The effusiveness and reflection he’d accessed so instantly in France—gone. Maybe he just didn’t have the time.

Once again he had nowhere to live. And no job. He wrote a letter or postcard to Jean Pierre roughly every other day, mostly to say that he loved him. Brian had remained a faithful friend despite everything and was basically supporting him at this point. They’d moved into Court Street temporarily with friends of Brian’s, downstairs from David’s old place.

The first thing David covered in his journal after his return, on June 6, 1979, was a trip with Brian to the West Village—“its immediate visual effect,” which he doesn’t describe except to agree with his ex-roommate Dennis De-Forge’s assessment: It’s an outdoor whorehouse. “Don’t think I’ll ever forget that initial sense of shock.” He didn’t elaborate, but clearly he wasn’t talking about cruising on Christopher Street. He meant the piers, which would become the center of his life for the next year and a half.

These rotting treacherous structures along the Hudson River provided cover for acres of public sex. The waterfront from Christopher to Fourteenth Streets was the unofficial gay men’s playground. Separating the piers from the edge of the Village was the elevated West Side Highway, which had been closed to traffic since ’73 but still provided shelter to transvestite hookers among its stanchions. On the city side of the highway were gay bars like the Ramrod, Peter Rabbit, and Alex in Wonderland. This big libidinous play district included the trucks parked along the highway every night and somehow never locked. Certain men preferred the truck ambience to the piers for casual sex. David would surely have been familiar with this area. He’d been frequenting the nearest dive coffee shop, the Silver Dollar, since his street days with Willy, but he usually picked up men on the streets or in bars. The piers could be dangerous, not just because they were falling apart and pock-marked with holes open to the river. Men had been murdered there. For many, the lawlessness and risk only added to the excitement. This was an autonomous zone.

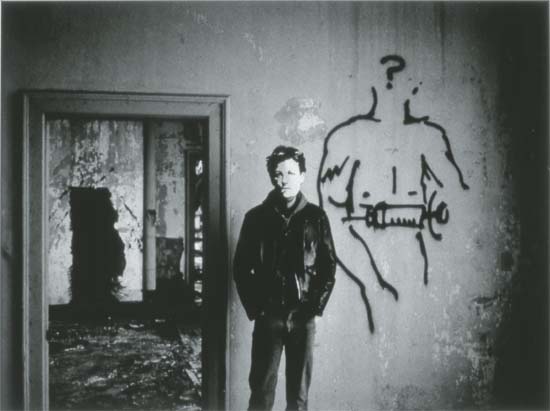

Sex among the ruins—David found it fascinating. He wanted to cruise the piers, but he also wanted to paint them, photograph them, and record what happened in them. Soon he was back with Brian and a can of spray paint. He drew a crude Rimbaud face on a windowpane. On a wall, he sprayed a male torso shooting up with a big hypodermic needle. Elsewhere he painted a target. Then he sprayed a kind of a haiku onto a wall: “Did you watch the dogfight yesterday (under Mexican sky).” He graffitied a line often quoted by William Burroughs: “ ‘There is no truth / Everything is possible’ Hassan I Sabbah” and added his own ten-line poem underneath, beginning, “Some men gun fast trucks down red roads / Down into distant valleys where mountains / Are slowly eaten by deserts.”

Other artists had already seen the possibilities in these abandoned structures. Gordon Matta-Clark, for example, had cut a large half-moon shape from the end of Pier 52, off Gansevoort Street, to create Day’s End in 1975, but David may not have known about this. While in Paris, he’d discovered Joseph Beuys—in a book. He’d been especially excited to learn of I Like America and America Likes Me, a piece in which Beuys lived in a gallery with a coyote for three days. A Beuys retrospective was scheduled for the Guggenheim that fall. In homage, he sprayed a Beuys statement on another wall: “THE SILENCE OF MARCEL DUCHAMP IS OVERRATED.”

David had one short-lived minimum-wage job that summer. In mid-June, an ad agency trained him to print photographs and to run a photostat machine. They fired him when he almost immediately started using his sick days. But while there, he was able to photostat the cover of Illuminations to create a life-size mask of Arthur Rimbaud.

Rimbaud was a kind of lodestar for David at this point in his life. He identified with the poet. They’d been born a hundred years apart—Rimbaud in October 1854 and David in September 1954. Both were deserted by their fathers and unhappy with their mothers. Both ran away as teenagers. Both were impoverished and unwilling to live by the rules. Both were queer. Both tried to wring visionary work out of suffering. David just didn’t yet know the rest—that he would soon meet an older man and mentor who would change his life (as Paul Verlaine had changed Rimbaud’s), and that he too would die at the age of thirty-seven.

He began photographing Rimbaud in New York that summer with a borrowed camera, using Brian as his model. In 1990, the first time these photos were exhibited as a series, David told an interviewer from the New York Native, “I felt, at that time, that I wanted it to be the last thing I did before I ended up back on the streets or died or disappeared. Over the years, I’ve periodically found myself in situations that felt desperate and, in those moments, I’d feel that I needed to make certain things.… I had Rimbaud come through a vague biographical outline of what my past had been—the places I had hung out in as a kid, the places I starved in or haunted on some level.”

Brian posed in the Rimbaud mask on Forty-second Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, a block then lined with porn theaters. He stood in front of dangling cow carcasses in the meatpacking district. He rode a graffiti-scarred subway. He spent quite a bit of time at the Hudson River sex piers and wandered among various other crumbling eyesores. He posed at the dancing-chicken booth in Chinatown. He stood outside the Terminal Bar. He shot heroin.

David wrote two “35mm photo scripts,” with dozens of ideas for the poet’s adventures. He had a narrative in mind. Rimbaud would arrive by ship, alighting at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in one script and at Coney Island in the other. Eventually he would die of a heroin overdose. Most of these scenarios were never photographed—like Rimbaud eating in the Salvation Army cafeteria, Rimbaud inside Port Authority, Rimbaud making rude gestures at St. Patrick’s during mass—probably because David lacked money for film and processing. Usually he economized on what he did shoot. Rimbaud on the subway: two exposures, one printed. For the heroin shot, he removed the needle and replaced it with a pin, its point inside the hypo, which he’d glued to Brian’s arm. “The head of the pin was pressed into the flesh,” Brian said. “It looked like it was in the flesh.”

Arthur Rimbaud in New York (Pier, Junkie), 1979. From a series of twenty-four gelatin-silver prints, 10 ×8 inches each. (Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York)

John Hall also took part in the Rimbaud project, though he doesn’t remember when. He posed at the piers and in the meat-packing district as Brian had. (David used the images of Brian from those locations.) He was also Rimbaud wounded (bandaged hand) and Rimbaud with a Dubuffet sculpture. Most famously, though, John Hall was Rimbaud masturbating. He remembers nothing about where this photo was taken or how it came about, only that David put him at ease when he thought he was too skinny and didn’t have a good body. Brian thought the photo might have happened when David went to photograph Hall’s apartment, whose disarray he found fascinating. Indeed, David even described the place in his journal: “The hurricane dive that seems to be John’s symbol, obsessively in turmoil—wild in a sense—I photographed parts of it for the images—the clash of headlines and food containers and loops of stereo wires and bass guitar—piles of papers sliding down hills of music magazines and newspapers. Posters of the Slits and James White on the walls—ashtrays of cigarette butts from guests who came and departed weeks ago.” The Ludlow Street building was so old and decrepit that, according to Hall, tenants had been known “to fall through their living room floors into the apartment below.”

Arthur Rimbaud in New York (Coney Island), 1979. From a series of twenty-four gelatin-silver prints, 10 ×8 inches each. (Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York)

When Jean Pierre came to visit, David quickly incorporated him into the project as well. JP became Rimbaud at Coney Island. JP remembered going two or three times. They’d leave at five A.M. to get there when it was deserted. He remembered the black jacket and white T-shirt he wore. Alone on the beach. Alone at the closed kebab stand. Alone in front of the parachute drop. JP could not remember where they stayed. Not Brooklyn, he thought. David still hadn’t found a place to live.

All that summer and fall, David and Brian bounced around. After Court Street, they lived with Dolores for a couple of months, taking the bedroom while she slept on the couch. They crashed in a photographer’s studio. They stayed briefly with Susan Gauthier and Steve Gliboff in the East Village. Sometimes David talked about looking for work, but he didn’t look. He was drifting again.

During this first year after Paris, he devoted a great deal of time to the piers. He’d spent his first night there with John Hall early in July. Just as John’s presence had once helped him to cross the country freight-hopping, now it seemed to reassure him about beginning to cruise the piers. He did his graffiti there during the day, but at night, you couldn’t even see the floor until your eyes adjusted. David and Hall just dipped into the warehouse between Perry and Charles Streets and watched men drifting through it, then headed back to the Silver Dollar for English muffins. They dropped in at Dirk Rowntree’s place, where Dirk photographed them. David and Hall walked out talking about no-wave bands, how good it was that they always broke up so fast and “nothing gets stale.” They moved on to Tiffany’s, a Sheridan Square coffee shop with terrible food and a colorful Christopher Street clientele. Then on to the Bank Street pier, which was open, and there they discussed the propriety of watching public sex—while they watched it “from a discreet distance … as it is an intense visual to be confronted with,” David reported. That’s when Hall proposed, for the first time since suggesting it by letter, that he and David should have sex, and David decided that if they were ever going to do it, this was the right place. They entered the warehouse again, but just as they started to make love, they heard shrieks and terrified, moved out along the river, where they found themselves trapped. Then the source of the racket, a gaggle of drag queens, burst out through the doors a few yards away. Outside, along a “U-shaped arena of warehouse walls and windows,” they found “miraculously” a cheap rug to lie down on, where they watched the disappearing night, the waves slapping up from tugboats and barges, and they finally made love. All night, David had been carrying Burroughs’s Algebra of Need. He lit a cigarette and looked up at the World Trade Center, “the very top of it emerging into a dim sunlight of rising dawn. It was framed by crossbars of metal on top of the far warehouse roof and it was like some kinda vision in all this.”

Arthur Rimbaud in New York (on the subway), 1979. From a series of twenty-four gelatin-silver prints, 10 ×8 inches each. (Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York)

While the Rimbaud project was under way, he wrote nothing about it in his journals. He said nothing to the posing Rimbauds about what it meant to him. And he wrote nothing about Jean Pierre, who visited for most of August.

That summer he pasted into the journal his first drawing of a burning house. Somewhere he had seen the work of Saul Ostrow. “Desire one of his fire images,” he wrote. “Stuff haunts the head.” David was then having an affair with a guy acquainted with Ostrow. By September, he’d begun corresponding with Ostrow himself. David told me, “Ostrow was doing paintings of burning houses, and we had a correspondence of at least six or seven letters between us where we sent each other burning houses in the mail. Like, I’d find a logbook for a fire department from 1950 and do dotted lines in bold that he could cut, and make a burning house out of this paper. Things like that.” It would take another two years for the burning house to become one of David’s stencils, and one of the first images associated with him. In the journal, on lined paper, the burning house just sits behind a man in the foreground with a dog-head puppet on one hand saying, “If he’s following my scent … this’ll throw him off.”

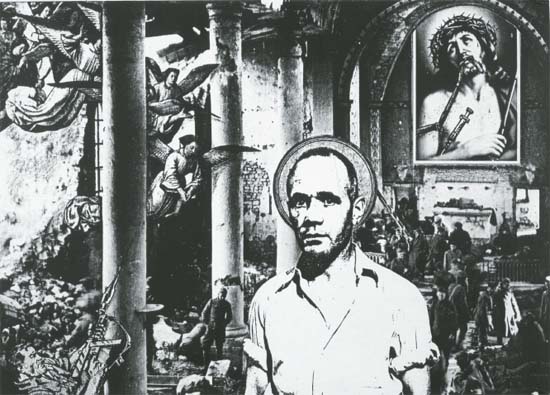

He’d started making “to do” lists. One from September includes this instruction to self: “Do a Saint Genet collage—go to Strand for a copy of his photo on Funeral Rites.”

He also made a first rough sketch for this. Untitled (Genet) became controversial in 1990 because it includes an image of Christ shooting up. When he began it, he was working with images of the sacred and profane and seems simply to be questioning, what is evil? And by extension, what is good? He was just beginning to find his subject matter.

The original sketch is overly busy. He wants to set this scene at the waterfront, with Genet in the center, a Madonna and child looking down from a fortress at the right, and a large ship “possibly with flame inside” at the left. Salamanders without legs rain down on the ship. There’s an eclipse. Onshore, left, two men are fucking. He’s thinking the Madonna should have a weapon, maybe a cigarette. His second sketch is much simpler—just Genet on the left and the Madonna and child in a window to the right. He still thinks it should be set at the waterfront, and this time the baby Jesus holds a pistol.

But no. The waterfront suggests his own life—the piers, and his father the sailor. Madonna and child—that would be the Catholicism he knew as a young boy. It would take him till the end of the year to work this out, to see that the piece had a meaning beyond his own life, and that it is about sorrow. In the final version, he replaces the waterfront with a war-ravaged church. David had been very aware in France of all the people around him who’d come through the war, often at great cost. Genet’s lover had died “on the barricades” in 1944. Funeral Rites is the story of his grief. David has angels flying in from the left side of the picture and at bottom, one comic-book machine-gunner firing bullets toward heaven. Genet wears a nimbus.e David may well have skipped Sartre’s critical study, drawing inspiration simply from the title Saint Genet. But he’d read all the novels. He particularly loved The Thief’s Journal, telling JP in a letter that the book had made him feel good about his own early life. The Thief’s Journal presents a world of inverted values, where criminality is a way to oppose the social order and evil can be the path to sainthood. David may also have noted lines such as, “Going into mourning means first submitting to a sorrow from which I shall escape, for I transform it into the strength necessary for departing from conventional morality.”

Untitled (Genet, after Brassaï), 1979. Photocopied collage, 8½ × 11 inches. (Private collection)

As for the junkie Christ destined to so upset the American Family Association, it creates balance with the criminal Genet who’s been exalted into sainthood. But where Genet wants to transcend his sorrow, Christ wants to embrace it, because he has chosen to identify with “the least of these.” Jesus describes this to his followers who will get into heaven by saying, I was hungry, I was sick—and you fed me, you visited me. “Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.” In David’s mind, he could have added, I was a junkie, I was a bum, I was a lonely drag queen trolling the piers.

One night David and Brian went to the Christopher Street pier and sat on the loading dock of the abandoned warehouse under a streetlamp, reading Genet’s Funeral Rites out loud. David had begun the practice of going to the piers to write. He’d pick up a cup of coffee at the Silver Dollar and sit with his journal in the yellow streetlamp glow that came through the side of the warehouse. He was there to record the whole scene, including its architecture and ambience—headlights moving across a wall, the sound of tin doors banging, water slashing at pier posts. Later, he would tell me that he saw these dying structures as symbols of what was essentially a dying country. In the first journal entry he made after visiting the pier with John Hall, he wrote, “It’s so simple, the man without the eye against a receding wall, the dog’s head impaled against the surface: the subtleties of weather, of shading.”

It was the first draft of a piece he would include in Close to the Knives in 1991: “Surrounded by shadows, the mudcaked floors and harsh scent of urine in damp corners, men moving with unbuttoned shirts, teeshirts tied around thick waists, dreams falling in dense heaps along the stairways, last flies of summer circling the busted windows, his hands red and moving thickly where his lips traced lines down on the belly.”

By mid-September 1979, David had noticed that his “Marcel Duchamp” line was flaking off the wall, and someone had thrown rocks through the Rimbaud face he’d painted on a window.

But he would have heard nothing of the following news, also from September ’79: Two young gay male New Yorkers went to their doctors complaining of odd purplish lesions on their bodies. Kaposi’s sarcoma, declared the doctors—baffled, since KS was a rare cancer that usually appeared among elderly men of Mediterranean or Middle Eastern descent. The disease these young men would soon die from would not get the acronym “AIDS” until 1982.

One day, David went to the piers to draw, but the wind made it hard to manage his paper. He ended up helping the warehouse’s self-appointed artist in residence, Tava, carry paint cans inside. Tava was working on a huge mural of two men masturbating that would cover the back wall. David had encountered Tava before, in a former washroom among the broken shards of porcelain, and had watched him paint a giant hand on a giant cock. David thought of Tava’s work as “thug frescoes.” Outside, facing every passing boat, Tava had painted two men with huge erections, like two caryatids, as tall as the central doorway.

David loved just hanging out in this ambience. The piers were a glimpse of life outside the approved social structure. And the pier denizens were more than sexual objects. They represented what the hoboes in Paris had represented. “They can be seen as a physical rejection of society’s priorities; which elevates many of these characters in my eyes,” he’d written to a friend regarding the hoboes. Sex just added to the fascination—and the layers of meaning.

In October, David had a sexual encounter at the piers that he mused over for days:

I’m losing myself in the language of his movements—he drifted, turned on his heel in grey light and passed into a quiet room with torn walls and glass “paymaster” windows boarded over on the other side. A hermaphrodite was scrawled on the wall near the broken window, lines of rain slowing to a halt.… I moved towards the stranger in the leather jacket, the brief motion of his body eyes and hands a brief shuffle in the vacant room, the swirling of fine shadows in the corners, the grace of his movements, all contributed to erasing the formality of being strangers, we eased towards one another and my jacket swung loose and to the side; blue colors of light, blue moving effortlessly over his face, the red glow of the skin making the hands luminous as they passed over my legs to my crotch. I slipped my hand between his shirt and smooth chest, fingers touching lightly to his nipples as he rubbed slow and hard with his hand. I felt his neck and grew hard and he unzipped my trousers, drew them down slightly, a strong palm beneath my balls, face lowering slowly as he squatted and took me into his mouth. I bent my torso forward and rolled my hands down the linings of his collar, smoothed out the shadows and the heat of his skin, felt my blood had been removed, boiled slowly and then replaced, warm currents in the forehead and stomach, sleep rolling outside in the hallways in coils like rope. He stood up briefly as I tongued his chest, running my lips over his belly and chest, sucking at his nipples, caressing his smooth sides, his arms encased in leather, the leather becoming an extension of his flesh only in the way that belongs to men who have graceful animal movements and sexual energies running through their corded arms and legs. I felt a sweat run down my body in the cold air as is the case, rare that it is, when I’m in the company of a man like this; a culminating sense of time and age and direction coasting on a single track towards walls of life lived, felt naked as I came and grabbed his shoulders and shook him violently ramming my cock into his mouth with each movement, grabbed his hair between my fingers and stroked his face and neck and skull and embraced his back and shoulders and blew out shadows and bleak visions of sky and rain and water and blew out delirium from the base of my skull, felt heavy and lightweight simultaneously, felt a pitch of heat in my chest and belly, and he rose to his feet, said: whoah … really good, and I blushed slightly, all these unspoken sentences at the tip of my tongue.

Before they parted, David learned that the man was originally from Texas—and though the guy didn’t live there anymore, David added that image to his musings. The cowboy. The pickup truck. The drive toward endless vistas with a bullet in the dashboard—the romance of that. This was about freedom. The fact that he connected anonymous sex with possibility. He decided that he’d never yet lived the life he wanted. “Really it’s this lawlessness and anonymity simultaneously that I desire, living among thugs, but men who live under no degree of law or demand, just continual motion and robbery and light roguishness and motion, reading Genet out loud to the falling sun overlooking the vast lines of the desert … aimlessness in terms of the senseless striving to be something, the huge realization of the senselessness of that conscious attempt in the way this living is really constructed.”

David decided that if he was living his life for anything, it was for this man from Texas—not that individual so much as what the encounter represented, “the combination of time, elements, visuals, visions, light, movements, all associations … as if that past moment holds everything that will make my life valid, that will save my life.” That was the sense he had until he wrote it down, and then he was faced with emptiness, “having tasted a real freedom, a freeing of myself from this life from this city rotating with the world on its axis.”

Writing about sex at the piers always sent him into these reveries, even when he was not personally involved. One day he watched as men drifted toward a corner of a warehouse to watch a blow job—like metal filings drawn to a magnet—and the scene spiraled out in his mind to the vistas he wished to travel and then back again, to his own mortality, to his wish to extend time, to turn sunsets “into lifelong moments, unbreathing, no need for food, no need to scratch or shift, the lengths of measure contained in the dragging feet of the large man who follows me from room to room, emptiness shadowed by rusting floor safes and broken glass that holds pieces of sky along the dark floorboards.”

One of the men he met “along the river” took to him to see his first opera, Le Prophète. Tedious, David thought, except for the parts where he had to pinch his leg to keep from laughing. Afterward, David showed this man his artwork and could see that he didn’t like it. How was it, he wondered, that his imagery was so threatening to those who enjoyed the established order? How could he explain that his images reflected energy he’d picked up “in society, in movement through these times? It’s just a translation of what takes place in the world.” But sometimes he questioned himself about why he was so drawn to imagery that unsettled and disturbed. Once he’d kept his life hidden. He wondered, did he now keep beauty hidden?

In November, David and Brian finally moved into their own apartment, in a desolate Brooklyn neighborhood called Vinegar Hill just north of DUMBO (down under the Manhattan Bridge overpass). DUMBO felt deserted and dangerous in the Seventies. A few artists had moved into old industrial buildings, but there were no grocery stores, newsstands, or Laundromats. Just one seedy bar stood between the York Street subway stop and the Brooklyn Bridge. Vinegar Hill was even harsher and more isolated. The blocks between the subway and their apartment at 59 Hudson Avenue were industrial, mostly cobblestone, and inhabited at night only by packs of stray dogs. It was a fifteen-minute walk that felt like an hour. But the apartment had five rooms. Out the back window they could see the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Out the front they could see the Manhattan Bridge, and beyond it the Brooklyn Bridge. They kept a three-ring binder to which, every day, they would each add an artwork: a drawing, a found object, a poem, a collage. They had no telephone.

Brian paid the rent. He worked the graveyard shift at the Empire Diner in Chelsea, as a short-order cook. David had a few short-lived jobs, often acquired through men he met cruising. Mostly he painted the occasional apartment, though one guy got him a job with decent pay in a piano factory. David quit after a week. The labor was exhausting, the commute too long. Early in November, David went to a clinic on Forty-second Street and sold some blood. Then for a couple of months that winter, he worked at a bookstore again, but it folded.

For David, these were “grey and confusing times.” This was the year he began admitting to his sense of mortality, at least in the journals. He was now twenty-five.

He dreamt he’d been buried in coarse brown earth, all the way up to his teeth. That image again—of his own partly buried face. But it doesn’t seem to be a death dream. One molar’s been exposed to air, it’s throbbing, and after running “with cutthroats,” he returns to his own burial spot to lift out the aching tooth. He sees that it’s rotten, filled with maggots. He feels he mustn’t scream since it’s his own tooth. He’s given a shot of morphine and feels secure. “The matter of having no home becomes something relegated to the self of the past.”

By the end of 1979, he’d rewritten the piece about the piers, which he now called “Losing the Form in Darkness.” The four paragraphs in his journal appear almost verbatim in the final version:

It’s so simple: the man without the eye against a receding wall, the subtle deteriorations of weather, of shading, of images in the flaking walls. Seeing the quiet outline of a dog in the plaster, simple as the splashing of a fish in dreaming, and then the hole in the wall further along, framing a jagged sky swarming with glints of silver and light. So simple, the sudden appearance of night in a room filled with strangers, the maze of hallways wandered as in films, the fracturing of bodies from darkness into light, sounds of plane engines easing into the distance.

He did the first of many drawings of a factory with one large smokestack, like the one on the Jersey side of the Hudson that he could see from the West Side piers. He drew this factory, with reindeer, on his Christmas card for JP.

He still wrote to Jean Pierre once or twice a week. For all his fantasies about “freedom” and living with thugs, he also fantasized about going back to JP. This would be a lifelong internal struggle: the urge to roam versus the longing for stability. He responded to warmth in others with such hunger, wanting to connect. But when he did, it scared him. On December 30, he wrote to JP: “For the first time in my life, I don’t have any idea what will happen to me—I think sometimes that I would like to return to Paris.”

On that same day, December 30, a tremor hit the downtown art world, but the shift in tectonic plates was so small that few noticed it at the time. This was the day that some thirty-five artists—their bolt cutters in a guitar case—broke into an abandoned city-owned building on Delancey Street and set up “The Real Estate Show.” The artwork, in every medium, addressed how “artists, working people, the poor are systematically screwed out of decent places to exist in,” according to the East Village Eye. Few people ever saw this exhibit, which opened on January 1, 1980, and included works by Rebecca Howland, Jane Dickson, Bobby G, Christy Rupp, Mike Glier, Edit DeAk, and others. Police closed it on January 2. But no matter. In retrospect, “The Real Estate Show” was a conceptual project, and the idea that it had happened was much more consequential than anything exhibited. The city responded to the break-in and attendant agitprop by giving the artists another building on nearby Rivington Street. It became ABC No Rio, its name lifted from a sign fragment across the street. No Rio not only preceded the East Village galleries but also outlasted them.

Ironically enough, the artists had never intended to start an “alternative space” in the neighborhood. They were members of Colab (a.k.a. Collaborative Projects), a nonprofit set up to do thematic shows and access funding. They were the harbingers of new energy in a stultified art world. Members included Jenny Holzer, John Ahearn, Kiki Smith, and others who felt they had no access to that closed world. They were also “political” and acutely conscious of what it meant to bring their work into a neighborhood off the art world’s beaten path. In 1978, Colab member Stefan Eins had opened a storefront art space called Fashion Moda in the famously blighted South Bronx. Fashion Moda connected graffiti and hip-hop artists with the downtown scene. Graffiti writers were beautifully “bombing” the trains. At least, most artists thought so. Wait on any platform and a masterpiece might roll in.

Charlie Ahearn, also a Colab member, would begin working on Wild Style in 1981. The film starred real graffiti writers and rappers like Lee Quinones, Fab 5 Freddy, and Lady Pink, with a small featured role for Patti Astor as the intrepid journalist who goes to the Bronx to do a story on them. Astor was an actress in no-wave films and a self-styled blonde bombshell who would open the first East Village gallery in the summer of ’81. “There seems to be little doubt these days that the story of the ’80s is going to center on the merger of the South Bronx and the East Village,” wrote Steven Hager in a cover story on Astor for the East Village Eye. Who knows? Maybe that could have happened if artists were really in charge. Wild Style ends by making an uptown-downtown connection when rappers and break-dancers perform at the East River Park amphitheater just off the Lower East Side—a vandalized eyesore until Quinones paints it into glory.

In 1980, gentrification seemed eons away in the South Bronx, while Delancey Street—and Rivington, and Grand—were literally within walking distance of Soho, then the epicenter of the art world. The artists could foresee the changes in which they would soon play a part. One of the idealists involved in “The Real Estate Show” promised in a letter to the architecture magazine Skyline, “In the past, artists have been forced to move on once they had adequately defined new real estate values. This time, on the Lower East Side, they intend to stay put and help determine the area’s evolution.”

Shortly after the New Year, David had a big argument with his mother and told her he’d never see her again. That night, he dreamt that he’d run into Jean Pierre on the subway. They talked like old friends. JP had just found an apartment in Chicago, or was it Washington, D.C.? After they parted, David realized that he didn’t know and had no address for him. “Jean Pierre is lost to me,” he thought inside the dream. “He feels for me but feels its best not to continue. World seems to be crashing apart for me. I feel upset as hell.” Then, still in the dream, he rationalizes it. Birth always meant there’d be loneliness. He goes home with a guy he meets on the street, a “jerk.” Looking out the window in the jerk’s apartment, he sees Dolores scaling the side of the building. They’re on at least the tenth floor. She’s huffing and puffing and losing hold. He opens the window and grabs her hand, pulling her inside. She gives him a look. “Sadness in there.” He turns and now his mother is on the couch with some wealthy middle-age man. The guy is pulling out gifts. David is disgusted, thinking his mother must be going for money. “I sit there wondering if I’m made of the same desperate actions.”

Though he did not yet identify himself as a visual artist, he entered three pieces in a juried show at Washington Square East Gallery. The art had to be a foot square or smaller. There were three thousand submissions. On January 15, he found out that he’d be one of 457 artists in the show. They had accepted one piece of his, a self-portrait. He wrote to Jean Pierre, “Now I have something to put on a resume.”

But what this acceptance triggered internally, which he decided he could tell no one, was a sense of himself in time: “a sense of the aging self, a sense of how much I want to do and experience, no country in the world could hold that much.”

He was still sad about his argument with Dolores. He decided that he’d vented his anger and frustration at her for not being what she could be when, really, he was mad at himself for not living up to his own potential. “I guess what scares me more than anything else in my life or in my box of fears is that I won’t be able to exercise my senses, my leanings in the time period of my living.” He was soon in touch with his mother again.

On a small paper bag he made notes for an installation or performance (never realized). He would appear shirtless, carrying a piece of timber from the piers like Christ going to his crucifixion. He’d attach a clock to the timber. He’d crush animal skulls, shells, and fossils underfoot. And he kept drawing that power plant. Sometimes with one smokestack, sometimes with two.

He’d started a new project—portraits of men. This went on for months, with Brian his most frequent subject: Brian blindfolded. Brian in a bow tie. Brian at the barbershop. Brian at home. Brian on the sand, against a wall, in a car, lying on grass, shooting up. Brian as St. Sebastian at the pier, standing in what used to be an office or a cubicle. And of course, Brian as Rimbaud. He began shooting more Rimbauds at the end of February. Brian remembered always complaining, “I don’t wanna,” because he worked nights and David was constantly after him to “ ‘get up, get up.’ “

Fire ravaged the pier warehouse at the end of January 1980. When David went to inspect the damage a few days later, he found that some of his graffiti had gone up in flames. In the main section of the covered pier, he found an old ratty couch on an upraised ledge and a barrel cover set up on a box “like some wino’s living room.” Upstairs the entire roof had burned. Steel girders twisted like snakes poked into the sky. Some areas were impassable now, “rooms and rooms of crushed plasterboard, cinders, ash heaps, a couple walls with strange graffitied frescoes done in crayons of altars and angelic faces and swooning winds and muscular bodies.”

He noted in his journal on February 8 that a sheet of corrugated iron had been nailed over the walkway that led into the covered pier. He did at least half his cruising closer to home now, along the waterfront in Brooklyn. But mere iron would not keep determined men off the pier for long. On March 6, David was back at the warehouse watching drag queens pick their way through the charred wreckage while a group of men scoured the place for copper to sell. The guy he made it with that night was built like a weight lifter and had a couple of large feathers hanging from one shoulder of his jacket by a piece of string. David wrote, “[This] decoration … perplexed yet gladdened me for it threw meaning into his image, as if it were a tribal gift.” Later he drew a picture of it in his journal.

David had begun to feel distance growing between him and Brian, though on certain days it would seem “okay” again. He was also editing more of his life from the letters to Jean Pierre, which he still sent once or twice a week. Naturally he’d never mentioned his sexual encounters, though I don’t think either of them expected fidelity. But when he met a French man at the piers who took him to Los Angeles for a couple of days, he told JP only that he might go—that he’d been told he could find work there. JP apparently responded with some concern, because David’s next letter assured him: “I thought I would possibly go to Los Angeles only if I cannot come to Paris by summer.… Remember I love you.” (Actually, Los Angeles had been “a kind of refuge,” he told the journal, “from thoughts about Paris and the constant limbo I feel I’m in.”) He didn’t tell JP about the drugs either. David tried heroin for the first time in late March. He was with Brian and friends of Brian’s including Sister Roxanne, “nurse of the Nether-worlds,” who selected the best needle from a fistful of hypos and shot them all up. Just days earlier, he’d injected cocaine with Brian and his friends from the Empire Diner, then gone to the Mudd Club—which David thought “bourgeois” but, he wrote in his journal, “with friends it’s endurable.” He told JP only about dancing there and about escaping a mugger in the subway by leaping into an F train just before the door closed, then finding himself surrounded by homeless men, asleep across every seat.

David also met the poet Tim Dlugos that March and showed him the Rimbaud series. Dlugos wrote to his friend, the writer Dennis Cooper, who was then in Los Angeles editing a journal called Little Caesar. As Cooper remembered it, “Tim said, ‘I bought this hustler last night and he showed me some of his stuff and it’s really good.’ “

A hustler?

“Maybe it was ‘trick.’ I don’t know,” Cooper said. “But Tim sort of made it seem like he had bought him at the piers.”

If David had gone back to selling himself, he never said so. A “trick” could refer to someone he’d picked up. But David might not have been averse to a little cash “gift.” He certainly had not paid for the trip to Los Angeles with the French guy. The upshot was that, in April, David sent a package of sixteen Rimbaud photos and a couple of his monologues to Dennis Cooper, who agreed to publish all of them. There would, of course, be no payment.

At the beginning of May, David went out with John Hall to shoot pictures of trash in the squalid alleyway called Extra Place that ran behind CBGB’s. He’d been there a few days earlier, and he couldn’t help but notice that the rotting fish he’d photographed then had been stripped to the bone. As he approached a discarded sack of clothing, he realized that it was actually a man, and a gigantic bum called out to tell him he’d be in trouble if he photographed his sleeping friend. The bum pronounced himself sick of “you people coming down here and making money off us.” David told him he was just photographing the trash and had never sold a photo. So the bum told him that if he really wanted a story, he should write about “conditions,” the fact that sixteen hundred men a night couldn’t find a bed in a shelter. And young kids were coming to the Bowery dives and taking the spaces—when those kids could work. His sleeping friend was eighty-six years old and made about ten dollars a day washing car windows on Houston Street. As did he. David asked if he could come back and record their stories. Sure, said the bum. His name was Maurice.

David hadn’t abandoned his monologue project. In fact, he’d added a piece about a sexual encounter he had in February with “a young tough” who probably hadn’t slept inside for a week (by David’s estimate). They met on a bench along the river, where the guy was having trouble rolling a joint because his fingers were so frozen. David helped him, and then they walked down a ramp to have sex in an abandoned playground.f

Even if they didn’t become monologues, David was still making notes on intriguing marginal characters. Like the drag queen at the Silver Dollar with a cardboard suitcase under her feet and a cigarette held between shaking fingers, “writing letters with a chewed pencil and stuffing them nervously into envelopes destined for Texas.” Or the ravaged old “Genet” character who invited him to see his room in the Christopher Street Hotel, a room about twelve feet square and plastered with news photos of President Jimmy Carter, the First Lady, Carter’s mother, and the American flag. A large flag covered most of the guy’s mattress. He pulled out a greeting card featuring a seminude woman, “like a Vargas Playboy painting.” On this he’d written a letter to the president’s mother, explaining to David: “How do I know she didn’t look like this when she was younger?”

But if David ever found Maurice again, there’s no record of it. He did end up with a photo showing the lower part of a man’s body in a pile of trash.

The day he took that picture, he and John Hall went to Squat Theater on Twenty-third Street to see James White and the Blacks. The doors had opened at nine, but these were the days that clubs had to add the word “sharp” if there was any chance of the show beginning close to the advertised time. James White (a.k.a. James Chance) showed up at twelve thirty. David wrote a long description of his performance and the feelings of aggression it aroused in him. White snaked out into the audience touching people. He was famous for attacking spectators. When he grabbed a woman’s sweater and pulled her about a yard, David wanted to punch him. “I was gonna grab him by the hair if he fucked with me,” he then decided. “That’s the intense stuff he inspired—didn’t feel good contemplating it—just thought he was both brilliant and a creep.” Hall felt certain that the people there must have known White’s reputation for these assaults. Dirk Rowntree analyzed it as “a method of making you impatient for freedom—feeling the limitations or boundaries of your freedom by exiting from his self-made boundaries into yours.”

Soon after Dennis Cooper accepted his work for Little Caesar, David wrote to Sarah Longacre, editor in charge of the centerfold at the SoHo News, wondering if she’d be interested in considering his Rimbaud photos. She would. He met with her on May 7, after he’d spent the afternoon making new prints in a darkroom on Prince Street. She immediately asked if she could use the image of Rimbaud shooting up to illustrate a story they were doing on heroin. (It ran in the very next issue, one column wide.) She loved the whole series, but told David she wasn’t sure enough New Yorkers would know who Rimbaud was. She needed time to consult with the editor in chief.

That same week, between his meeting with Longacre and the appearance of junkie Rimbaud in print, David finally got a job. He ran into Jim Fouratt at Julius’s bar. They knew each other from hanging out late nights at Tiffany’s coffee shop. Fouratt had just opened a new club, Danceteria (with business partner Rudolf Pieper), and David asked if he might work for him. Fouratt told him that the only position still available was busboy. Fine, said David. He was so elated to get this job he nearly fell over a chair.

That night at Julius’s, he also met Arthur Bressan Jr., a filmmaker. David was thinking about making a Super 8 film. Arthur was all for it, said that’s how he’d started. They rambled around the Village, ending up at the Hudson River, where they had sex out on one of the piers. David would realize a couple of days later that he hadn’t even seen Arthur’s face clearly, but at the end of the evening Arthur had held David’s hand. David reacted to this gesture with “almost bewilderment insofar as people rarely do that in this city, much less when they hardly know you, and I really dug it.” He met Arthur again a couple of days later, feeling self-conscious because of the “honesty” they’d shared in talking and touching. They went to the pier, and Arthur told him he wanted to make a film about child abuse—actually a film about a man making a film about child abuse, in which a fourteen-year-old boy leaves his cruel parents and finds love with the filmmaker.g

Arthur thought that when kids had sex with older guys, they grew up suddenly—even adopted the mannerisms of an older person, while the older guy became more childlike. David thought this perceptive, based on his own experiences. He flashed back to teenage times when he’d been on the street: “The older men I’d lain down with and the recollection of my movements, my mannerisms with them, those scenes in dim-lit rooms in Jersey swamp motels manipulating a cigarette in my fingers and reflecting on my life and past while talking in a purposefully more sophisticated manner, out loud to the man unseen in the bathroom combing his hair before a fluorescent-lit mirror.” David was quite taken with Arthur and gave him the two Rimbaud prints he requested. However, Arthur thought that David wasn’t really a still photographer; he should be “doing cinema.” Nowhere does David say that Arthur made mostly porn films. Maybe that wouldn’t have mattered to him.

Arthur was at least ten years older than David and took a paternal approach. David had never been truly appreciated, Arthur told him, and had a sadness about him, a loneliness. David didn’t agree with this. The line that came into his head immediately was “I never feel loneliness,” but he didn’t say it out loud.

The affair with Arthur Bressan lasted most of May. That month, David sent fifteen cards or letters to Jean Pierre. He waited for a decision from SoHo News, and he began working at Danceteria on Friday and Saturday nights.

He was soon dismayed by his new job and disgusted with the clubgoers. His duties included keeping bartenders supplied with iced Heineken or Bud, carrying broken sacks of ice between floors, emptying garbage cans, pulling bottles or whole rolls of paper towels from toilets, mopping up vomit, and diving “through human walls of sweating pounding thrusting dancing bodies to sweep up broken bottles.” Arthur told him that the club goers thought destructiveness was anarchy, and if someone told them to do whatever they wanted with a window, they’d just break it. In a letter to JP, David complained, “Fou! The punk new wave people are becoming very boring to me.… [They] destroy anything they desire, break chairs, doors, light fixtures. I have to clean up after them.… These people have no imagination concerning what to do with freedom.” It was in this letter that David told Jean Pierre he’d met a filmmaker who was showing him how to use a movie camera.

The film David planned—silent, black-and-white, Super 8—would be all about eroticism in everyday life, i.e., cruising. But also about repression, represented by cops bursting into a room. A naked man would be bound to suggest “that waterfront/bar sexuality can be seen as either a result of, or an attempt to break the weight of social/political restraints.” He wrote two scripts for this film, which he never made.

Just before meeting Arthur, he’d written to JP: “I do not think I will be in love again in my life, except with you. These are honest words.” And they were. His anxiety about the long separation from JP seemed to intensify during the affair with Arthur, especially after he decided that Arthur wanted him only for sex. “I’m still very much in love with Jean Pierre,” he wrote in his journal near the end of May. “I still desire the chance to leave here and live with him in Paris. Jean Pierre was the first man to be completely relaxed and loving with me. Unafraid of my personality or my creative movements. There was room with him to love and live and grow and change. Time has put a distance between us. And my meeting Arthur filled up that kind of empty space.” He hadn’t even gone to the piers in two and a half weeks. But he felt that he didn’t have Arthur’s real attention. Something was missing.

Ever since David left Paris, he and JP had tried to figure out some way to get back together. Like dual citizenship—which would have allowed David to work in France but would also require his mandatory service in its military. Then there was the idea of entering a French university, but David didn’t have the money. That May, they had one last pipe dream between them: David would get a position with UNESCO. Jean Pierre knew a woman who worked there and she promised to help, but David had none of the skills or education the agency required.

It would have been easy to lose touch completely. David still had no telephone. Letters usually took about a week to arrive and sometimes as long as three. But now that David finally had some income, he hoped to visit France in August. He and JP had, of course, not seen each other since the previous August.

One day in Sheridan Square, David ran into his old friend Jim McLauchlin, a.k.a. Jimmy James Strange. McLauchlin had spent the past two years in India, as a Bagwan. He’d changed his first name to “Anado” and was driving a cab. “I was dressed in all orange clothing and had a religious medal around my neck—you know, total cult city,” McLauchlin remembered. And he decided that of all the people he’d known in New York, David was the one to whom he could give a book by his teacher. “David was a spiritual man, despite all the anger,” McLauchlin observed. That was the last time they saw each other.

David spoke on the phone around this same time with his old roommate Dennis DeForge, and was upset to learn that DeForge had been attacked and nearly killed on the Brooklyn Bridge. David thought of his own close call at the hands of the madman posing as a cop, and he remembered Lee Adler’s brutal murder. “Death coming so close to myself, to people I have shared part of life with.… Being in my midtwenties I sense the incompleteness that an unexpected death would be. I fear death and disablement, I feel the fear and horror of death coming close to friends.”

He was, however, moving away from his Court Street and West End friends and into a new orbit. Years later, when his old buddy John Ensslin showed up at St. Mark’s to hear him read, David acted, said Ensslin, “like a ghost from the past had just walked in.” Ensslin had moved to Colorado and into a journalism career, and he could see that David did not want to reconnect.

Around June 1, 1980, the SoHo News finally let David know that it wanted to run four of his photos in its centerfold: Rimbaud at Coney Island in front of the parachute drop. Rimbaud holding a small pistol in front of a “Jesus Is Coming” mural. Rimbaud at the pier with the torso-hypo graffiti. Rimbaud with a wounded hand.

Sara Longacre asked him to write something poetic to accompany the pictures. He gave her about two hundred words, with lines like “And some of us take off our dreams with our shoes and live in grand cities in day and night while still others move like sailors in a squall, passing among small islands and murmuring their imperfect truths to the shorelines.”

The $150 payment was the first he ever received for his art.

The day the paper came out, June 18, David walked for ten blocks with a copy before he had the nerve to open it. He loved how it looked. That issue of the SoHo News also carried an interview with Jayne Anne Phillips, which he pasted into his journal because she’d articulated exactly what he was feeling. She said of her book Black Tickets:

If it is about anything, it’s about displacement, deracination and movement—and the kind of distortions that happen when this movement is going on. Alienation is probably an end result of that kind of transience—I don’t think that it’s a bad thing to experience but it’s become a national mood. Now it’s possible for people to be absolutely in one place for years and feel as though they don’t belong there.… A lot of the voices [in the book] have to do with that kind of alienation that happens when you’re involved in a culture but you’re isolated within it.… If you can deal with aloneness in a way that finally lets you be unafraid, you’re prepared … for the big transformation and you know certain things about it before it even happens—not only death but passion as well.

He was printing Rimbaud photos into July. In the end, he had fourteen contact sheets, roughly five hundred images. He mailed twenty or thirty prints to JP, asking him to take them to a couple of magazines in Paris.

He had become head busboy at Danceteria and now worked three nights a week.

In July, the “Times Square Show” opened in a run-down former bus depot and massage parlor on Forty-first Street and Seventh Avenue with a hundred-odd artists including Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Jenny Holzer, and Kenny Scharf. A motorized James Brown cutout (by David Wells) danced just inside the door, setting the tone. This too was a Colab event, but a legal one.

Mired in inertia at the end of the seventies, the art world was aching for an act of artistic rebellion to kick it in the teeth. The astonishing success of the “Times Square Show” proved how bored everyone had become with sleek white walls, the formalist paintings hanging on them, and the hushed propriety in art’s presence. Jeffrey Deitch’s review in Art in America praised the show’s presentation and accessibility, how direct it all was: “entertainment, sexual expression or communication of political messages.” How wrong it would have looked in an elegant or even a clean setting. “Art must come to be marketed with the kind of imagination displayed by this exhibition’s organizers,” Deitch declared. These lessons from the “anti-space” would soon be confidently applied in the East Village.

But if David was even aware of this show, he did not mention it. He was still preoccupied with the riverfront, and the nonstop show around Sheridan Square: The woman at Tiffany’s coffee shop painting the frames of her sunglasses with purple nail polish. The drag queen from the previous year’s “hell hath no fury fight” (on Christopher Street with another queen) buying pills. Homeless men searching the garbage outside a bar for beer cans that weren’t quite empty. Someone in an apartment building at two A.M. throwing firecrackers at the winos on the stoop, though the winos were so drunk they barely flinched. The man with steel blue eyes on Christopher Street standing in front of the church with the wrought iron fence, then walking with David down to the warehouse that had caught fire. “He pulled me down to take him in my mouth.”

“Passing by the river awhile later … I threw a penny over the water and watched it sink—threw a penny in the river for history, for time and future archeologists and studying civilizations.” To David, this collapsing wreck would always be a monument. In just a few years, he would paint a picture called Soon All This Will Be Picturesque Ruins, featuring multiple images of the Acropolis as a backdrop to a crumbling building and a couple of the alien heads he created at the beginning of his career. Often he spoke of “the compression of time.” To him, Rimbaud was easily transposed to his New York. And we were all in the Acropolis, thinking it permanent.

At the pier, he’d seen some chunk of his own graffiti leaning against a wall. One day in July, he filled two pages of his journal with descriptions of the “vagrant frescoes” still visible, the men moving over charred floors, the sexual motions in rooms that he passed—and he climbed a ladder to an unburned section of the roof where men lay sunbathing nude. He stood facing west and there he had a moment of feeling himself connected in defiance and exhilaration to all of America and all of its history from this epicenter of queer freedom. “I pulled myself up through the roof overhead and stood above the city and saw … the red hint of the skies where the west lies; saw myself in other times, moving my legs along the long flat roads of asphalt and weariness moving in and out of cars … dust storms rolling across the plains and the red neoned motels of other years and rides and the distant darkness of unnameable cities.”