Those of us who lived among the alphabet avenues in the 1980s grew accustomed to hearing a certain refrain: “Works! Works! Works!” The drug paraphernalia could be rented for just a couple of dollars, and needles littered the sidewalks and gutters. Neighbors complained about all the dealers at the corner. You had to elbow your way through the crowd in broad daylight and would be offered five kinds of heroin on the way to the grocery store. “That corner”—Second Street and Avenue B—“no longer belongs to the city of New York,” someone from a group of Loisaida block associations told the New York Times in the summer of 1983.

Heroin was a social drug in the eighties, and Alphabet City was its round-the-clock supermarket—or, as the police called it, “the retail drug capital of America.” Finally it was easy to find a taxi, people joked, what with so many cabbing in from elsewhere to buy drugs. David had described one kind of transaction—the cement block pulled from a sealed-up door and a hand reaching out. It could be that open, with a line of buyers down the street. But often the dealers hammered some cavelike entrance into a sealed building and allowed customers inside to line up on a rickety stairway lit with votive candles. Upstairs something would usually be rigged at a door or landing to keep buyer and seller from actually seeing each other. Or, if the stairway was gone, someone lowered a bucket for the money, counted it, then lowered the bucket back down with product. Millions of dollars were changing hands.

To an outsider like me—a non-drug user—this was a world of gothic scenery. I’d see ruined buildings down the street a-flicker with candles every night. These were the forbidding cryptlike shooting galleries. Often I saw users on the street, dipping and swaying like cobras. One day I walked out to see someone who’d ODed sprawled on the sidewalk, surrounded by a crowd debating whether he was dead or alive. He’d turned blue. Just then, an ambulance rolled up and the EMTs calmly revived the guy. As if they did it every day, and they probably did.

The most unexpected feature was the din, at least in summer. One night I visited a friend who lived across from one shooting gallery and next to another on East Third. We could barely hear each other over the screams from the street: “Works!” when the coast was clear, or “Bajando!” (“It’s coming down”) when cops were near. Cars with out-of-state plates were lined up as if headed through a drive-in bank.

Community groups had been clamoring for more cops for years, and occasionally they’d get them—standing on corners along Avenue A, when everyone knew the action was on Avenue B and beyond. Certainly the police made arrests. Sometimes there’d be a whole line of perps standing against some abandoned building with their hands up. But they’d all be back the next day. So, when the NYPD began Operation Pressure Point in January 1984, I did not expect much to change. But this would prove to be more than just another sweep. Operation Pressure Point lasted for a couple of years. By January 1986, the NYPD had made 17,000 arrests in the neighborhood, more than 5,200 of them for felonies, while seizing 160,000 packages of heroin. The courts couldn’t even keep pace. New U.S. attorney for the Southern District, Rudolph Giuliani, stepped in to prosecute low-level street dealers one day a week in federal court, where they got longer sentences than they would have in the state courts.

Why did law enforcement suddenly get so serious? As the operation began to squeeze dealers out, longtime neighborhood resident Allen Ginsberg told the East Village Eye: “It’s seemed to me to be the policy for the last 20 years to destroy the community of the Lower East Side. Apparently the supply of junk has been manipulated by the powers that be to drive the poor out of the neighborhood: use the junk population to burn down the area. The deed is done.” That sounds like a conspiracy theory, but it jibed with what I witnessed.

When I lived between Avenues C and D in the seventies, I was aware of some drug dealing, but it was nothing like the open-air drug bazaar of the early eighties. Everyone I knew who’d been flushed out of Loisaida because of drugs—because they couldn’t take one more break-in or mugging—fell into the “working poor” category: struggling artists or Puerto Rican families. In the early 1980s, the East Village lay at the cutting edge of the gentrification process.

After David returned from Europe at the end of February 1984, he visited the art piers with a French photographer, Marion Scemama. This was the beginning of a passionate friendship that lasted for seven years—but a relationship of such ups and downs that for several of those years they were not on speaking terms. They went to the piers so Marion could photograph David for a French-language magazine, ICI New York. David took her both to Pier 34, which she’d visited the previous summer with so many others, and to Pier 28, which few people had seen. (The derelict structures were still six or seven months away from demolition.) Marion had been active in left-wing politics in Paris, and they got to talking about the Red Army Faction, the West German terrorists sometimes referred to as the Baader-Meinhof Gang. During this conversation, Marion felt something click between her and David.

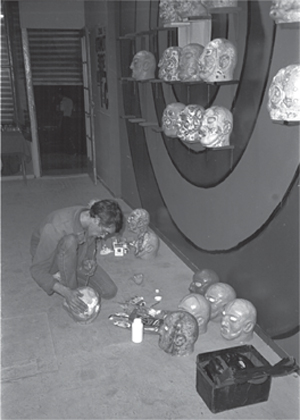

A couple of weeks later, Dean Savard called her to ask if she could photograph David for his next Civilian show. They were doing a poster, and David had suggested hiring her. Feeling too shy to go alone, Marion asked her friend Brigitte Engler to accompany her to the tiny Fourth Street apartment where David now lived alone. (Tom Cochran had moved out, probably at the end of ’83.) The central room, the kitchen, was filled with new sculpture. Plaster heads. Not yet painted. David was using the oven to dry some of them. Marion photographed him seated among the heads, wearing shades and puffing on a cigarette, the essence of boho cool. Then they smoked pot and talked until two in the morning. From that point on, David called Marion nearly every day. They’d meet for breakfast and talk for hours over coffee after coffee.

Beginning with Kiki Smith—or maybe with Peeka Trenkle and Susan Gauthier—David had relationships with certain women that were very intense but never sexual. Marion filled that slot now that he and Kiki had retreated from each other a bit. He was still seething over her comment that she wasn’t going to have children with him, while she’d begun to feel that it wasn’t good for her emotionally to be, as she put it, “so deeply invested” in a relationship with a gay man. Nor did she identify with the aesthetics of the East Village or want to be part of that scene.

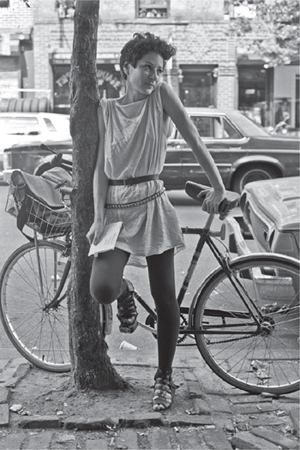

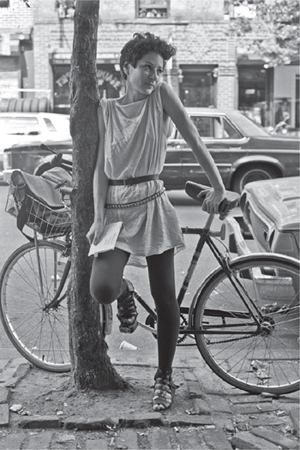

Marion Scemama in 1984. (Photograph © Andreas Sterzing)

At the time of my interviews with David in 1990, he and Marion were in one of their “up” phases. He explained that they had a “friendship that was beyond friendship,” that when they met “we were both dealing with a lot of dark stuff, working out things from our pasts.” He thought she had an interesting mind.

Marion introduced David to Catherine Texier and Joel Rose, who’d just started their insanely labor-intensive Lower East Side fiction magazine, Between C & D. The publication was actually a fanfold computer printout sealed in a ziplock bag with handmade East Village art on each cover. (Price: four dollars.) For their second issue, released in summer 1984, they accepted a piece David wrote about his hustling days, “Self-Portrait in 23 Rounds.”

Even though the neighborhood galleries embraced everything from graffiti (at Fun, for example) to conceptualism (at Nature Morte, for example), I knew what people meant by an East Village “look”—a kind of cartoony figuration, painted quickly, probably meant to register quickly, often helped to that end by simple shocking imagery. By that standard, the quintessential East Village artist was Rick Prol, whose paintings all featured skinny men in business suits with knives stuck through their necks, or some variation on that theme. Prol also curated one of the quintessential East Village group shows, “Underdog” at East Seventh Street Gallery, which included David’s work. The same issue of the Eye that covered the NYPD’s Operation Pressure Point also carried interviews with Prol and another artist Mark Kostabi. They made it clear that a deep cynicism had already infected the scene.

Prol said he’d gone through art school hearing that painting was dead, but “then painting found itself again by letting itself be stupid.” As for curating, artists were willing to do anything, Prol declared. “You give them a group show called ‘Shit in a Road’ and they’d paint pictures for it.”

But Prol’s was the voice of innocence compared with Mark Kostabi, who liked to say that his middle name was “Et.” (“Mark-et.” Nudge, nudge.) He told the Eye: “Paintings are doorways into collectors’ homes.” He was still a few years away from opening his own version of Warhol’s Factory, Kostabi World, where assistants would manufacture his work for him—a practical approach for someone who regarded his paintings as mere “product.” Kostabi would later claim to be a satirist. And maybe he was. In August 1985, while a gaggle of East Village artists painted a mural at the Palladium nightclub, Kostabi threw fifty bucks in singles out over the dance floor and watched people dive for dollars. The problem was that Kostabi’s persona rather overwhelmed his actual artwork. A documentary on him that appeared in 2010 was titled Con Artist.

By March ’84, some thirty galleries had opened. At Fun, Patti Astor and Bill Stelling had taken to wearing sweatshirts that read “The Original and Still the Best.” Nicolas Moufarrege, that early enthusiast, published a piece called “The Year After” in Flash Art that summer. The key word was now deal, he reported, when last year it had been show. “The underground Bohemia of last year is now an all-out new establishment with all the intrigues that this engenders,” he wrote. While he thought there were good artists at work, “there are too many fastly painted pieces; neo-expressionism and ‘bad painting’ have made it easy for many to pick up the figurative brush.” He hoped this did not signal “the beginning of an era of ‘souvenir’ art and tourist boutiques.”

Nowhere was the blatant commercialism of the scene embraced more openly than in a now-classic piece by Carlo McCormick and Walter Robinson that appeared in Art in America that summer. “Slouching Towards Avenue D” cheerfully described the East Village as a “marketing concept” suited to “the Reagan zeitgeist.” The neighborhood itself, with its poverty, drugs, burnt-out buildings and crime, they called “an adventurous avant-garde setting of considerable cachet.” I found this statement shocking, but they were also naming something real. Tour buses would soon arrive to show the curious-but-timid what the artists had wrought amid the rubble. Art in America allotted twenty-eight pages to a celebration of the scene’s history and artists. Then, two pages went to Craig Owens for his retort: “The Problem with Puerilism.” In Owens’s view, the East Village was “an economic, rather than esthetic, development.” But had anyone pretended otherwise? He decried the appropriation of “subcultural productions” (graffiti, cartooning). Was this an East Village problem? He criticized the scene as a “simulacrum” of bohemia. But it felt real to me.

What can be seen in hindsight was that reality and hype were tumbling over each other so quickly that both reactions were possible. The whole concept of marginality was in flux here. The media spotlight pushed cultural change at such a velocity that bohemians barely had a chance to stew in their legendary juices before someone was there trying to decide if they were the Next Big Thing.

On April 23, 1984, Health and Human Services Secretary Margaret Heckler appeared in Washington with Dr. Robert Gallo to announce that he had found the virus that causes AIDS. This should have been good news. Instead it marked one more spot where progress had snagged. French scientists at the Pasteur Institute had actually isolated the virus almost a full year earlier. In other words, a couple of months before the death of Klaus Nomi. Not that it would have helped Nomi. There were no treatments. But the news that this was an infectious disease might have been useful to know, even if no one could say for sure how it was transmitted.

Gallo had shown in 1980 that a retrovirus he called HTLV caused a rare form of leukemia. His hypothesis was that a related retrovirus caused AIDS. The Pasteur Institute scientists sent Gallo samples of their retrovirus, which they called LAV, in July ’83 and again in September, to establish that it was not a leukemia virus. Gallo announced at the end of that year that he’d discovered the cause of AIDS: HTLV-III. The assistant secretary for health asked him not to make the finding public just yet. It was an election year and credit for the discovery was to go to the Reagan administration, to the president who would not even utter the word “AIDS.”

By March 1984, however, the Centers for Disease Control had proven that HTLV-III and LAV were one and the same. The CDC director let the news slip in a March 28 interview with the New York Native: The AIDS virus had been discovered—by the French. The New York Times picked up on that and ran a story on April 22. Which forced Heckler and Gallo to make their announcement the next day.

Ultimately, the French scientists got the Nobel Prize in Medicine, while it was Gallo who demonstrated that the virus first isolated at the Pasteur Institute is the virus that causes AIDS. So everyone contributed, but the controversy over credit had a negative impact on research. As Randy Shilts pointed out in And the Band Played On, scientists working internationally on AIDS were forced to take sides, and certain good virologists opted out to avoid the politicking. Meanwhile, it was time to develop an antibody test, and while Gallo sent samples of the virus to pharmaceutical companies, he did not send any to the CDC until the end of 1984 because the agency had leaked news of the discovery and he saw it as allied with the French.

In April 1984, however, very few people understood the significance of these events or the magnitude of the crisis about to engulf them. The issue of the Native that broke the story on the virus did not even give it a cover line. It was just one more theory at that point. More coverage went to the possible closure of the bathhouses.

On April 15, 1984, Mike Bidlo re-created Warhol’s Factory in the attic at P.S. 1.

Bidlo appeared as Warhol and spent the evening making silk-screen prints of “Marilyn” to give out gratis. Silver foil covered the walls. Naturally, the not-quite-Velvet Underground performed. Keiko Bonk—a painter, musician, and friend of David’s—put the band together and played Nico. Julie Hair was John Cale while David played Lou Reed and sang a creditable rendition of “Heroin.” He also dropped acid for the first time in his life. Dean Savard wafted through the crowd dressed as Edie Sedgwick. Rhonda Zwillinger appeared as Valerie Solanas. Many who’d been there commented later on the crush and the rhythmic bouncing on the floor—remembered indelibly because they thought it was going to collapse.

That month David was engaged in finishing work for his show at Civilian. He had made twenty-three plaster heads with, as he put it, “a couple of extras that were separated from the series,” which he called Metamorphosis. They looked like the alien heads he’d started to include in a few paintings. No two were alike. A few were covered with maps or parts of maps, others were painted, the colors of the eyes changing “according to what colors mean spiritually,” he said. Then halfway through the progression, the heads showed signs of distress: bandages, blood, black eyes, incineration, and finally one “fell off the shelf.” A twenty-fourth head sat on the floor in a doctor’s bag, an old one. He said the piece was about the evolution of consciousness. With perhaps the attendant consequences. He’d been thinking, twenty-three genes in a chromosome; a twenty-fourth causes mongoloidism. (That was also the reasoning behind the story that was about to appear in Between C & D, “Self-Portrait in 23 Rounds.”) Some of the individual heads were photographed, but the piece as a whole was never documented. David threw one of the “extra” heads into the Hudson as a sort of offering.

He’d begun to refine his private symbol system. He continued to work with maps, which remained forever mysterious to him as an acceptable version of reality. Ripping them could be a metaphor for so many things, like groundlessness and chaos. He’d stopped working with garbage can lids and driftwood. The new sculptures used animal skulls, skeletons, mannequins.

To look at David’s early work is to watch him figuring out how to be an artist. A painting he did in 1983 called The Boys Go Off to War is a kind of diptych, and the imagery is simple. On the left half are two men, naked to the waist, perhaps in a bar (since one holds a drink), perhaps lovers but at least friends (since one has his arm around the other). On the right are two gutted pigs. With the paintings he did for the 1984 Civilian show he was really beginning to develop his collage approach. For example, Fuck You Faggot Fucker features, again, a male couple. The background is all maps but the only one clearly visible is behind the couple at the center. Created with a stencil, they stand waist-deep in water, kissing. Directly below them is a scrap of paper found by David, on which some anonymous homophobe has written, “Fuck You Faggot Fucker,” around an obscene doodle. He’s embedded that in the painting. At the four corners are photographs: one of Brian Butterick as St. Sebastian, photographed at the pier; three of David with John Hall, naked at the Christodora.

David’s show with the plaster heads, other sculptures, and new paintings opened on May 5, 1984. Though none of the principals, including David, knew it at the time—this would be his last solo show at Civilian. I remember the opening because everyone stood out on Eleventh Street watching David inside, finishing the work. He’d hung the show earlier, placing the heads on a wall where he’d painted a big bull’s-eye. Then he left, and the twenty-three heads started to slide off their shelves. The wall was just Sheetrock with no studs. Savard and Marisa took them all down in a frenzy and rehung them on the opposite wall, where Savard repainted the bull’s-eye. Then they had to rehang everything else. David, who’d probably been sitting in some restaurant, came back furious. He didn’t like Savard’s bull’s-eye. I remember him standing inside with a paintbrush—opening delayed. What he said to me about it later, though, was that he liked the way that broke the art-world rules. You couldn’t go to an opening in SoHo or on Fifty-seventh Street and find the artist still standing there with a bucket of paint.

Earlier that day, David had argued with Alan Barrows about Fuck You Faggot Fucker. Barrows remembered, “I said, ‘David we can’t have that name.’ It really bothered me. And he said, ‘Well, that’s the name of the painting.’ I said, ‘Can’t you change it?’ I was thinking of these prissy people coming in.” The critics. The collectors. The art crowd. They’d be offended. David adamantly refused.

David installing the plaster heads at Civilian Warfare on May 5, 1984. (Photograph by Philip Pocock)

He then responded to Barrows with a work of art, though Barrows didn’t know it until he saw the piece at a New Museum retrospective six and a half years after David’s death. There was the familiar image of the two men kissing, this time stenciled over two contact sheets. The one on the right shows Jesse Hultberg at the pier; he’s naked in most of the pictures and either wearing a dog mask David made or posing as St. Sebastian. No doubt David intended to contrast Jesse, who was literally willing to expose himself, with the reserved Barrows. The contact sheet on the left shows Barrows in photos David took during their European trip. In one, right near the center, Barrows is sticking his finger down his throat over a plate of bad food at the Berlin airport. So, Barrows realized, “because I had trouble with it, he’s forever connected me with that image, and now this”—it’s simply called Untitled—“is in the permanent collection at the Whitney.”

The Civilian show sold pretty well. David was becoming, in the words of Dennis Cooper, “a lion of the scene.” And around this time begin the stories of his frightening and often irrational rage.

It was sometime in ’84 that David got mad at Chuck Nanney and stopped speaking to him—snubbed him on the street, wouldn’t return phone calls. Nanney couldn’t figure out why. Finally their mutual friend Steve Brown let Nanney know: “David came over to your apartment while he was tripping, and you looked at him funny.” Nanney was astonished. And hurt. The rift was patched up eventually. They had so many mutual friends that it was hard to avoid each other. But they never actually discussed what had happened, and, said Nanney, “Something odd started to happen to our relationship after that.”

Then came an explosion at his ex-lover, old roommate, and onetime bandmate, Brian Butterick. One night Doug “Wah” Landau (who later opened King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut) pulled up at the Pyramid Club and asked, “Want to go to Provincetown for a couple of days?” Brian did. David piled in too, and Jesse Hultberg. They left after four A.M. when the club closed.

In the course of the four-to five-hour drive, Brian said something sarcastic and, he thought, innocuous. He did not remember the content, except that it had nothing to do with David. But David, seated in front, turned to him so enraged that his face had turned purple. He said something about how Brian was acting like a jaded old queen “and he peppered it with some really hurtful personal stuff,” Brian said. David wouldn’t drop it, either, until someone else in the car yelled, “Enough!”

“Everyone else was signaling to me when David’s back was turned,” Brian said. “Like, ‘What the hell is going on?’ It was so vitriolic and directed towards me, and I didn’t understand why he was mad. It wasn’t even about him.”

By now, Brian was one of David’s oldest friends, and he’d never seen him behave like this before. “He was usually held back,” said Brian. “With bad emotions. Good ones too. He had never lashed out at me.”

The two of them never discussed this incident. “I didn’t go there, because it was so nutty,” Brian explained. “I talked about it to the other people in the car.”

It was a preview of things to come.

Like most villages, this one reveled in gossip. At some point, a delicious story circulated that Gary Indiana had written a feature on David for Art in America, but then got so furious with him that he went to the magazine’s office and ripped the type off the boards. Carlo McCormick called it “common knowledge at the time.” Gary denied it, and Betsy Baker, then editor of the magazine, said that nothing like that ever occurred.

But what had happened between Gary and David in Paris didn’t end there. Gary was still in love, and now when they met on the art-world circuit, David acted as if they hardly knew each other. As Joe Vojtko put it, “The more Gary kept trying, the crueler David became.” Vojtko said that for many months, even years after, when he ran into one of them on the street, David or Gary would complain for what seemed like hours about the other. Vojtko thought they were both irrational on the topic.

David told people that Gary was stalking him. Marisa Cardinale remembered David coming into the gallery to discuss this, but she couldn’t recall specific incidents. “I remember more the emotional tenor,” she said. “I remember fraught conversations. Like, ‘What am I going to do? How am I going to get him to stop?’ “

Judy Glantzman, part of the Civilian stable and later a good friend of David’s, confirmed that “David was unnerved.”

But Gary adamantly denied that he did any stalking, and when David later wrote about Gary in the E ye, he did not mention stalking. Instead he complained, for example, about Gary leaving fifteen screaming phone messages in one night. Gary said he has never called anyone that many times in a day, but in a short letter to David he wrote, “I’m sorry I terrorized your answering machine Saturday night. The more direct thing would have just been to scream in your face.” David also charged that Gary was writing him letters of “up to twenty pages outlining how I was still a prostitute.”

“We said a lot of things to each other,” Gary said. Which isn’t exactly a denial, but there is a surviving letter (of five and a third single-spaced pages) in which Gary says, “If you can’t cop to the fact that everyone is corrupted by the need to make money, maybe it’s because you’ve never transposed your experience of being a hustler to the market for works of art.… Don’t you imagine that part of your public image, like Kathy Acker’s, has ANYTHING to do with your willingness to expose yourself sexually, and the sexual attraction to you of the viewer/reader/spectator, whatever?”

David was writing letters too. Once the two of them made up—years after this—they agreed to destroy each other’s letters, which Gary did. David either did not or he overlooked a couple—quite possible since he always lived in chaos.

But until the end of his life, David believed that Gary had spread stories about him that hurt his career. He thought, for example, that Gary told people he was a junkie. Gary denies this—and it’s not clear that such news would have discouraged anyone’s interest. Look at Jean-Michel Basquiat, a notorious heroin addict who practically had collectors lined up at his studio door. David also claimed, for example, that Gary put other critics up to writing bad reviews of his work. Gary denies it, and it’s hard to imagine any critic taking such direction.

I have spoken to everyone in the art world who’s in a position to know, asking them to speak off the record if they must, but to answer the question: Did Gary hurt David’s career? What everyone has told me is that David hurt his own career. Whenever his work was most in demand, he would stop painting.

In 1984, Lydia Lunch moved back to New York after spending several years in Los Angeles and London. By the age of twenty-four, Lydia had worked with more than a dozen bands, starting with Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, starred in at least a dozen underground films, and become a pioneer in what would later be called “spoken word.” As a self-described catastrophist and contrarian, Lydia liked to rant. Underneath the fierce persona, however, Lydia—like David—was as much a seeker as an agitator.

That spring, she invited David to participate in several spoken-word events she set up at the Pyramid Club: “Readings from the Diaries of the Sexually Insane and Other Atrocities,” “The Grand Finale of the Memorial Day Parade of Idiots,” and “The Weekend of Emotional Abuse.” Other participants included Vojtko, Richard Kern, Thurston Moore, and Victor Poison-Tete. David probably read from his monologues. He’d written some new ones based on stories he’d heard from Bill Rice and Alan Barrows.

Reminded years later of her menacing titles, Lydia laughed. She’d forgotten them but had a clear memory of what mattered back then to her and the artists she was close to: “We were just so disgusted with the hypocrisy of everything, whether we were talking about sex or money or the police state or personal relationships. Everyone felt that they had to do these performances, had to paint these pictures, had to make these films. They were driven to get it out of their system. To expel into the world what was trying to kill us or silence us or just beat us down.

“We lived with a toxicity in our blood or in our brain or in our psyche that drove us in an explosive way to try to create,” she said. “We were going as fast as we could because we didn’t think we were going to be around much longer. It’s not only about AIDS. It’s that you didn’t think you could last because you were going to burn out one way or another. It seemed that it was already written for you. That you better do as much as you could right now. Maybe because some people had already gone through so much and they couldn’t take much more.”

Lydia didn’t know a lot about David’s life but was drawn to the immediacy of his work. “He made it sound like ‘I experienced it, I wrote it, I took it to the stage.’ That was very attractive to me,” she said. “He was just a spontaneous performer or artist. Not trained, like myself. Not trained. So in a sense we came from a similar background or maybe a mind-set. There were a few people that were really hard-core people just because they were hardcore from circumstances beyond their control. David was one of those. You knew that the experiences were written deeper than the paper he was reading from.”

Vojtko recalled performing with his boyfriend, David Said, at one of Lydia’s “Weekends of Emotional Abuse.” They’d prepared a piece about AIDS, “Secret Love (From a Room at the End of Everything),” using money to record tapes of ambient sound that should have been applied to their overdue electric bill. Fellow readers like Kern and Henry Rollins had attracted what Vojtko saw as an aggressively heterosexual crowd that night. Over the weeks of performing with Lydia, Vojtko remembered, he and Said and David had grown bolder in their “willingness to push the limits and to flaunt the grimy details of [their] sexuality in ways that made the humorless straight crowd uncomfortable.” On the night Vojtko and his boyfriend did the AIDS piece, they brought it to a cacophonous crescendo, banging on metal and breaking furniture. “Half of the crowd was weeping and applauding, and the other half was shouting obscenities and throwing things at us. It was just the kind of reaction that Lydia liked best.”

Later in the dressing room, Lydia divided the door money among the performers. David tried to give Vojtko and Said his share, saying that he was selling paintings now and didn’t need the money. Vojtko and Said told him they appreciated the gesture but couldn’t take it. At home later, Said went into his backpack for cigarettes and was astonished to find a wad of twenty dollar bills—more than David’s share of the door.

In June, when Luis Frangella traveled to Buenos Aires to visit family, David went with him.

“The colors here are colors that brought me close to fainting,” he wrote in a letter to Hujar. He loved the drives with Luis into the countryside and the jungle. They stayed for a couple of days near Iguazú Falls and went hiking. David ventured out into a raging stream above the falls, his feet on bamboo while he held a vine overhead—as Luis screamed, “Come back! You’ll be swept over the falls if you slip!” David laughed at him. Until the bamboo broke. He managed to pull himself back to dry land, heart in throat, and found Luis “in the forest too sick to watch me anymore.”

He hadn’t gone to Argentina to work, but David rarely stopped working. No doubt it was Luis who arranged for him to show at the Centro de Arte y Comunicación. David created A Painting to Replace the British Monument in Buenos Aires on a street poster—burning race horses running below a large smoking alien with one eye a British flag, the other an American flag. One of the other pieces he made, Altar for the People of Villa Miseria, refers to a shantytown he’d visited with Luis, where he’d seen “huge families picking around mountains of smoking garbage.” The major elements in this sculpture: a human figurine seated in a wood cabinet painted pink. A red hand reaching for that human. A loaf of bread on the shelf below, cut in half and sewn together with red thread. All of this on a plinth. A Mayan statue sits at the base of the plinth. Above it all hangs a torn red banner. In a real departure, perhaps an experiment, David also painted about twenty watercolors in a sketchbook, mostly landscapes, which he never chose to exhibit.

He hoped he could come back to Argentina, he wrote Hujar. He would learn the language and travel the continent. But something changed in his relationship with Luis during this trip, according to Marisela La Grave, the young photographer who’d met them at the pier. David and Luis had had an affair, and Marisela thought that Luis broke it off during this trip or maybe just after. He discussed it with her. David and Luis remained friends, however.

David got back to New York on July 8. A couple of weeks later, Jean Pierre came to visit. According to Marion Scemama, David had decided that his relationship with Jean Pierre was over, but he didn’t know how to tell him. So David proposed that they take a trip—the three of them. He rented a car and drove them first to Virginia Beach, then to the Outer Banks—two spots he’d come to love during an earlier vacation with Kiki Smith, probably in ’83. As Marion remembered it, David was nervous and paranoid for much of the trip. One day in a restaurant, when Marion and JP began conversing in French, laughing at something, David stood up and went to sit at another table. One night David left them alone at the hotel for most of the night. Then there was the fight in the car when David said something so insulting to Marion (she couldn’t remember what) that she demanded to be let out so she could take the train home. He let her out, then came back and got her. “David could be really mean with people when he didn’t know how to handle the situation,” she said. Jean Pierre didn’t seem to remember any of this, but he is also the sort of person who doesn’t want to speak ill. He maintained that he and David never broke up.

In 1984 Richard Kern began making Super 8 films like The Right Side of My Brain, a collaboration with Lydia Lunch. She plays a woman drawn to increasingly abusive men—though they’re never abusive enough for her. In the film, she loves how she feels with a man when she’s “squirming under his fist.” It would have looked like a work of pure misogyny if Lydia herself hadn’t written the script.

David in Richard Kern’s Stray Dogs. (Photograph by R. Kern)

The Cinema of Transgression reveled in depravity, deliberate ugliness, and amorality. A line from Right Side of My Brain summarizes the whole ethos: “We’ll take the bad with the bad and make it worse.” Some of the films that came out of this movement were just silly, but Kern had enough talent to create others that were truly horrifying. Most of his films revolve around sexual power plays, with an emphasis on bloodletting and self-injury.

Kern asked David to appear in “Stray Dogs,” one of the four sections of a film called Manhattan Love Suicides. David plays a man identified as “a fan” who’s obsessed with an artist (Bill Rice) and follows him home. For some reason, the artist allows this demented fan into his apartment. David wildly overacts—mugging, leering, and twitching. The artist paints while the fan jerks off. Then the fan approaches, and the artist pushes him away. The fan begins literally to explode, first bursting a blood vessel in his neck, then losing an arm. That gets the artist interested. He wants to draw the fan, now lying in a puddle of gore. The cheap special effects are one of the film’s major charms. David loved playing out this cartoon version of repressed emotion. It was done over a weekend, and David kicked in $250, which probably covered most of the budget.

When David analyzed his attraction to the Cinema of Transgression later on, though, he didn’t even discuss the movies. He said that he’d found a group of people who saw “unarguable truth” in violence.

The art world had turned upside down. Suddenly, a Fifty-seventh Street gallery could close while full-page ads in Artforum might be purchased by the occupant of an unheated shoebox between Avenues A and B. It took me quite a while to realize that this was largely an illusion. No one had actually uncovered a pot of gold in the East Village. Hardly any of these tiny galleries made big money. Hardly any of them would survive the scene.

Civilian Warfare, for example, was a hot gallery with a horrible cashflow problem. The gallery had no backers, and no one working there had any business training. Major collectors would walk out with a number of pieces and promise to pay, for example, a thousand dollars a month. The gallery had to pay rent, utilities, and three salaries, along with the artists whose work had been sold. “We didn’t understand the ramifications,” Marisa said. “You can’t call your artist and say, ‘We sold ten pieces,’ and then not be able to pay them. We wouldn’t have been able to pay them in years, at the rate money was coming in.… And I was making, like, two hundred dollars a week.”

Back in more innocent times, someone had once come in and paid cash for a piece—a large sum. Savard was there, and Marisa, and David. Maybe Barrows too. “We laid the bills out end to end because we had never seen that much money before,” Marisa said. “I don’t remember how many thousands of dollars, but it took up a lot of the floor.”

In March 1984, however, David deposited a check from Civilian for forty-five dollars, and it bounced. In May, he sold quite a bit of work from the plaster-heads show, but the gallery could not afford to give him his cut. Not all of it, at least. Marisa remembered David and Savard arguing over it.

One day David came into the gallery and saw a receipt push-pinned to a shelf in the back—a receipt for a limousine ride. Savard and Gracie Mansion had taken a limo together to an event uptown, and they were dividing the cost, so Gracie had brought the receipt over. Apparently Savard had some sort of explanation but David couldn’t hear it. “He was livid. Just screaming,” Marisa said. “We were spending this money, and he hadn’t gotten paid. He could not be talked down. He stormed out.”

Savard’s drug problem hadn’t yet begun to wreak havoc with their everyday operations. It was his spirit that was driving Civilian Warfare. People who knew the gallery’s directors would describe Alan Barrows with words like “steady” and “mature” while Dean Savard was “charismatic” and “outlandish.” Judy Glantzman analyzed it this way: “Dean’s strength was also his weakness. That very far-reaching ambition and imagination made Civilian what it was. He was a visionary.” But then he’d go too far. He reveled in hyperbole. The gallery’s summer show that year was called “25,000 Sculptors from Across the U.S.A.” Glantzman estimated that there were maybe a hundred pieces crammed into the storefront. And that was amusing. But she also remembered being with Savard at the home of some important collectors one night and feeling embarrassed by his absurd fabrications. That particular night it was “we’ve sold five hundred thousand dollars’ worth of work.”

“He was a pathological liar,” said Barrows, who believed Savard’s stories for years and then suddenly saw that they didn’t add up. Marisa agreed: “He told gigantic lies. He said he’d been raised in Vietnam and was airlifted off the roof of the embassy at the end of the war. He used to bleach his hair and people thought he was Scandinavian—they couldn’t wrap their mind around the fact that a man would bleach his hair. So he told those people he was born in Sweden.” He’d told Alan that his father was in Kuala Lumpur.

In August the East Village Eye reported that Civilian Warfare was going to buy a building—another fantastic lie from Savard. What did happen that summer was that Savard and Barrows decided to leave their storefront for something bigger. They weren’t playing anymore. (They definitely had a typewriter now, though according to Barrows, “Someone probably gave it to us.”) And they had to keep up appearances in the ever more glamorous and growing scene. Savard seemed to feel especially competitive with Gracie Mansion, and she was moving to a larger space on Avenue A while turning her old storefront on East Tenth into the Gracie Mansion Museum Store. Savard and Barrows found a place on Avenue B and Tenth Street where they would pay $900 rent instead of $550. They hired someone to renovate the space, then couldn’t pay him.

David went to Marisa and asked her if she would start a gallery. Luis came to her with the same idea. But she didn’t want to own a gallery. She stayed with Civilian and was there the day David came to the new space on Avenue B and demanded his slides and his clippings. “He said he was going to have a show at Gracie Mansion,” she remembered. “It was terrible. Dean cried.”

David walked the one block to Gracie’s with his loose slides, press releases, and clips in a shopping bag.