With his installation at Gracie Mansion Gallery in November 1984, David began addressing the events of his childhood for the first time.

He covered a child mannequin with maps. He added flames to the child’s arms, legs, and back. The burning child runs across the bottom of the sea. David brought sand into the gallery to create his ocean floor, and added aquatic plants made from newspapers. At the back of the sandy area he placed a map-wrapped cow skull clamping a small globe in its jaws. Suspended above this from the ceiling was a shark covered in maps. Looming over it from the back wall—the specter the burning child ran from—was a large four-paneled painting of an ocean liner titled Dad’s Ship. On another wall, he depicted impending doom on a larger scale with his painting Soon All This Will Be Picturesque Ruins. He lit the scene with tiny white Christmas lights and added a soundtrack he’d done with Doug Bressler from 3 Teens.

The day of the opening, scheduled for six P.M., David didn’t show up to install the work until five thirty—with Marion Scemama and Greer Lankton in tow. The opening was delayed for at least an hour and a half while they worked.

David had decided to include some of Greer’s work—six human figures, maybe a foot tall, with arms raised in supplication or distress, made from wire frames wrapped in black tape. Greer was a transsexual who made dolls that addressed issues of gender and identity—their mutability. They could be “sissies” or hermaphrodites or Siamese twins, usually anatomically correct. She had had the first show at the new Civilian on Avenue B, but apparently it hadn’t sold too well. David put her in his installation because she needed money. The cow skull and Greer dolls were sold as a package. According to Sur Rodney Sur, the collector who bought them threw Greer’s dolls away and kept the Wojnarowicz. But Greer got paid.

David had also been invited to show with Greer at the Timothy Great-house Gallery in January ’85. David told Greathouse that he would do it only if he could collaborate with Marion. She was an unknown but Great-house wanted David enough to agree. “It was unbelievable,” Marion said. “I never showed in my life. David was the first person who said to me, ‘but you’re an artist.’ This guy made an eruption in my life and changed everything about how I considered myself.”

One night David and Marion went to a desolate site under the Brooklyn Bridge to stage a photo. David wanted it to look as if he’d been beaten. Queer-bashed. He lay back against an abandoned bathtub, a dazed look in his eye and fake blood coming from his mouth. Marion lit the scene with headlights from the truck they’d borrowed to drive there.

They would use this in one of their collaborations for Greathouse, and in a poster they were making for Between C & D magazine. David wanted to pair the photo with a text about a recent court decision ruling that homosexuals had no constitutional right to privacy, probably a reference to Bowers v. Hardwick, then winding its way toward the Supreme Court.o David also spoke of how a person could get away with murder by saying the victim was a queer who tried to touch him. So in his text, he becomes the aggressor. “Realizing that I have nothing to lose in my actions, I let my hands become weapons, my teeth become weapons.… In my dreams … I enter your houses through the smallest cracks in the bricks that keep you occupied with a feeling of comfort and safety.… I will wake you up and I will welcome you to your bad dream.”

Marion went home and processed the film immediately. Then she spent the night printing. “I start getting scared about having taken this photo” she said, “because I thought maybe one day he’s going to die this way. Because when you’re European, you have this image of Americans who just can come from nowhere, come with a gun and kill somebody if they don’t like what he represents. I thought maybe I took a fiction photo but one day it could be reality. So I called David. It was early in the morning, and I said, ‘I’m kind of scared of this photo.’ He said, ‘But do you like it?’ I said, ‘Just come and see it.’ It was six or seven in the morning, and I showed him the photo, and he said, ‘Wow that’s great.’

“But I said, ‘Are you sure you want to use this?’

“He said, ‘Yes, of course. Why?’

“And I said, ‘I feel a kind of responsibility about this image. Imagine that one day this happens to you.’

“And he got really, really angry. Really angry. I mean, later I understood that David could become angry at a point where you were not expecting it. But this was the first time he yelled at me: ‘How can you say that? If you say that, it means you want that for me!’ ”

So David began 1985—his year of fury.

He’d always had a temper, but now he was leaping into rages that were both irrational and damaging to some of his closest friendships. He and Marion went on to make four or five pieces for Greathouse. They produced the poster for Between C & D (which was folded into quarters and slipped into each ziploc bag). They remained on speaking terms. But David withdrew. Marion didn’t understand it. She just knew that suddenly “something was gone, something was broken.”

Years later, David tried to analyze his ups and downs with Marion, and he made the following notes about this first break with her: “Couldn’t leave me alone—together all the time. I asked for a week alone. I thought I was going to kill myself or that she was pushing me to kill her. Asked for week. She said yes. She called screaming about poster collaboration in show. I rejected her.”

David did put the poster in a group show without telling her. Then she happened to see him on the street and asked why. He replied, “I don’t need to tell you everything.” That made her so angry that she went to Keith Davis’s loft, where they’d stored the posters, and crossed her name off each one with a black marker. “It was a way of saying, ‘OK, I don’t want this to be considered a collaboration.’ Which was infantile,” Marion says. “Later Keith told me that when David saw that, he laughed.” However, David told people later that he had crossed off Marion’s name. Whatever the case, this was the beginning of discord.

Allen Frame had continued to experiment with Sounds in the Distance after the run in Bill Rice’s garden. He took it to Berlin during the film festival there and staged it in someone’s loft. Then at the end of November 1984, he directed Sounds at BACA Downtown in Brooklyn. The new cast included Steve Buscemi, Mark Boone Junior, John Heys, and Richard Elovich. They didn’t get reviewed, but Frame was gratified by the packed houses and positive feedback from theater people.

This time, David did not hesitate to attend, and as Frame put it, “he was not that gracious.” Frame had been much more ambitious this time. He had fifteen actors instead of eight. He had sets. One actor stepped out of a locker room at the back for his monologue. Another stepped out of an office party. One woman performed a monologue zipped up to her neck in a steam sauna. Onstage until intermission was a sculpture by Robin Hurst—a house sitting on a train trestle.

Frame asked David what he thought, and David responded, “Do you have four hours?”

David’s complaints amounted to the fact that he didn’t want these monologues reinterpreted. He could accept the locker room and office party ideas, but he certainly hadn’t gotten a story from anyone in a steam sauna; he wouldn’t have been interested in such a person. And how could the truck driver monologue be assigned to a woman—who then played it as a lesbian trucker? Changing the gender changed the content. On the positive side, one actor sounded so much like the guy he’d originally talked to that David was floored.

Frame felt disappointed that David saw things so literally but dutifully took his “notes” back to a couple of the actors—who were not happy to hear them.

David spent most of January 1985 in Paris, and while there he purchased some real human skeletons along with a baby elephant skeleton. He shipped them in one big crate to Keith Davis’s loft. Keith seemed to have infinite patience for any adventure or demand, if art was involved. When he left David a phone message saying, “Termites are coming out of the elephant; we have to bomb it some more,” he did not sound perturbed. David told people that the baby elephant had died in a game preserve, crushed in a closing gate or maybe electrocuted on a fence.

In February David bought a car—a green ’67 Chevy Malibu station wagon. He’d been renting cars periodically ever since he first had some money. Often he just drove to New Jersey with Hujar or Steve Doughton or Marion Scemama or some other friend to visit junkyards and swamps. He loved looking for snakes, frogs, and bugs. David and Hujar were especially fond of the industrial wasteland near the Meadowlands and another such site along the Hudson at Caven Point. They would both take pictures.

Almost immediately, David began adding tchotchkes and totems to the dashboard of the Chevy. Doughton recalled that among the very first was a figure of the leprous St. Lazarus, attended by helpful dogs. Then came the items that seemed to have floated off one of his paintings—a small skull to which he’d added bulging eyes and fangs, globes, dinosaurs, a bust of Jesus wearing a crown of thorns, assorted monsters, and a hollow green, red, and yellow frog. He once told Tommy Turner that the spirit of the car lived in the frog and had to be fed. Look inside, he told Turner, who found himself staring at a mound of dead grasshoppers, moths, bees, and other bugs collected from the grill and the windshield. A Day of the Dead skeleton decorated with baubles hung from the mirror. Over the glove compartment he eventually pasted a bumper sticker reading “I Brake for Hallucinations.”

One night near the end of February, a big crowd gathered at 8BC for an art auction to benefit Life Café, a sort of community canteen that was having trouble paying its rent. The New York Times sent a reporter to cover this exotic event. The club, “a dark ruin,” was packed. The unnamed auctioneer had accessorized his full-length evening gown with a beard and red hornrimmed glasses. Bidders held up not paddles but numbered paper plates.

The dramatic highlight came during the bidding over a sculpture by “David Wojnarowicz—the hottest among hot East Village artists.” It was a cat’s skull, two inches high and covered with maps. Bids jumped in $25 and then $100 increments. When they hit $800, the auctioneer cried, “Push it to a thousand! Think what you’d be doing for the community!” It topped out at $1,100 to wild applause.

The custom at benefits was for artist and beneficiary to split the proceedings, though an artist could always decline to take his half. David did take his $550, but not for himself. Early in March, he stopped in at the old Civilian Warfare storefront, which had become Ground Zero. Now living in the tiny back room were James Romberger, the artist who had once mistaken David for a lumberjack, and Marguerite Van Cook, then pregnant with their child.

James and Marguerite had become dealers almost by accident. Late in the summer of ’84, they’d curated an exhibit at Sensory Evolution Gallery called “The Acid Show”—so-called because they handed out LSD at the opening. The show was such a hit that it moved to a nightclub called Kamikaze for a short run. One of the artists they’d included was Dean Savard, thrilled to be able to show one of his own paintings for a change. Walking home from Kamikaze one night, they ran into Savard on the street. Civilian was about to move to Avenue B, and Savard said, why don’t you take the Eleventh Street space and bring the Acid Show there? He handed them the keys.

James and Marguerite ran Ground Zero in the spirit of the original galleries. “We’re not serious art dealers,” Marguerite told no less than the New York Times. “We do and show what we like.” David had heard from Marion Scemama that Ground Zero needed money at least as much as Life Café did. He had never even met Marguerite until the day he came by and handed her a check for $550. She did not allow herself to look at the check while he was there—thinking, wow, maybe it’ll be for fifty dollars.

The day after David wrote that check, he went to the opening of the 1985 Whitney Biennial. He had two paintings in the exhibition. He had wanted this since his first year at Civilian, and they couldn’t make it happen in ’83, when he was such a beginner. Now, just two years later, he was one of two “East Village” painters in the show. (The other was Rodney Alan Green-blat.) He’d arrived.

And he was terribly unhappy.

I remember running into him on the street—either after the plaster-heads show at Civilian or later that year when the Whitney announced who’d made it into the Biennial. When I congratulated him, he had such a look of distress on his face. He told me he just hated the art world. And then, I believe the exact sentence went: “If I were straight, I’d move to a small town right now and get a job in a gas station.”

Dennis Cooper also ran into him on the street, probably after the Biennial opened. Cooper, of course, had published some of David’s Rimbaud in New York photos and some of David’s monologues in his literary journal, Little Caesar. Cooper had moved to New York in 1983. He and David weren’t close, but Cooper always went to see his shows and he didn’t like the new work—the burning children, the kissing men, the shark. It was all so obvious, he thought. He liked the early work and thought David had “lost the quality of complete and pure alienation that had given his talent its bite and specificity.” So Cooper analyzed it in Artforum’s special issue on East Village art, published in October 1999. When he saw David on the street that day in 1985, he expressed these misgivings, “half expecting one of his famous bursts of temper,” Cooper wrote.

Instead, Wojnarowicz sat down with me on a stoop and launched into a tormented, self-righteous, hour-long harangue that has, ever since, struck me as definitive of East Village Art’s brief moment, for better or worse. He said that his success was destroying him because he couldn’t reject it in good conscience. He’d dreamed of this kind of recognition and had even fantasized about exactly the kind of black-sheep art world that the East Village scene encompassed in theory, a situation where art could be anything at all, and where walking into a gallery would always involve a disconcerting, confrontational experience with an uncompromised, individual vision. But this belief had been contingent on the idea that New York was secretly full of artists who had as clamorous a sensibility as his own. Instead, he found himself surrounded by peers whose talent was merely raw, and raw only by virtue of economic hardship, but whose sensibilities were as coddling and self-indulgent as those of the Salles, Fischls, and Longos who populated the official art world. As a consequence, similar delusions of greatness had settled over the scene. In response, he’d rebelled against his peers by giving his work a social conscience and physical grandiosity, both to counteract the ongoing romanticization of the homespun and to embody what he imagined an “East Village art” should be. But his rebellion had backfired. The political sheen had given critics and curators a way to pigeonhole his work and had led them to misdiagnose his personal rage as the spearhead of a movement with which he felt no camaraderie whatsoever. He said he was going to quit making art, and stormed off.

Of course, David did not quit making art. He just quit painting for the rest of 1985. The only picture in his oeuvre with an ’85 date is Attack of the Alien Minds, shown in the Biennial; that’s dated 1984–85 and features the same alien head he used in his May ’84 show at Civilian. A couple of exceptions were paintings he included in the installations that occupied him that year—which really began with the burning child fleeing Dad’s Ship, at Gracie Mansion. These are the scenarios he created after that: Parents eating their children. Parents being murdered by their children. (That was both an installation and a film.) Then, a burning child fleeing the apocalypse. He also began work on a film about a murdering “satanic” teen. A fourth installation, in a show that raised money for a child victims’ fund, featured a kid being hunted down like an animal.

What he realized later was that his newly secure foothold in the art world had relieved all that pressure just to survive—the pressure that had kept him from facing his past. “It was a rough time for me,” said David when I interviewed him. “I had more money than I’d ever had in my life. Which gave me access to time, gave me access to movement … and it shook up a lot in my life. I hit a really dark period. I think I became somewhat self-destructive, just—you know, I was hitting against that whole childhood.” He had tapped into a huge reservoir of neediness and rage.

In 1985, he didn’t just make one installation after another about imperiled children or dead families; he began to lash out at people who were “like family.”

Jim Stark, soon to start producing Jim Jarmusch’s films, decided to become the next to take on Sounds in the Distance after he saw the show in Brooklyn. He knew nothing of David’s reaction to that version. He just thought the material could use a bigger production and maybe get to a bigger audience. He enlisted a young director, Molly Fowler, who’d never heard of David but was fascinated by the monologues Stark showed her. Then they went to Gracie Mansion to look at David’s artwork.

“I fell in love with what I saw,” Fowler said. “I knew there was real power in where he’d been and what he’d seen.” Her thought was to incorporate David’s life into the script, “to keep each monologue on its own and use him to draw us from character to character.” She asked if she could spend some time with him.

“We met in various all-night restaurants on Second Avenue,” she said. “I don’t think we ever met before eleven o’clock at night, and we would sometimes talk for three or four hours about his life, about where the various characters came from, what he remembered about them, and how they’d affected him.”

A new version of Sounds in the Distance would open in November, but Fowler soon realized that, for David, these meetings at the beginning of ’85 were less about a theater piece and more about his need to tell someone his story.

Peter Hujar began a new project, setting out to photograph what he called “tribes,” meaning a kind of surrogate family. “Peter was amassing around him people that shared his ideas about life. That was your immediate tribe,” John Erdman said. “He loved to talk about his tribe.” Hujar had invited Erdman, then working more than full-time at the photo lab with Gary Schneider, to put such a group together. Erdman never did and always regretted it. Hujar soon got bored with the whole idea and stopped the project.

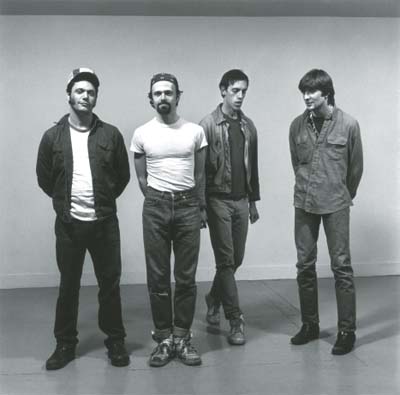

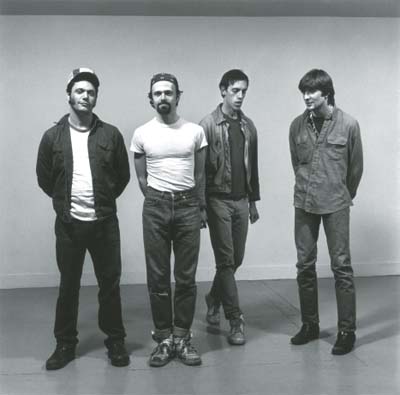

But he was thinking “tribe” when he photographed David in a group shot with Chuck Nanney, Steve Brown, and Steve Doughton. Hujar selected these people. Nanney remembered him saying, “You guys are inseparable and you have this really intense relationship that I admire, and I just want to capture this moment.”

David agreed to it, but had he assembled his own group, he might have included Keith Davis, for example. Some of his message tapes from this era survive, and the two Steves, in particular, seem to have called almost every day, sometimes more than once. Apart from art world activities and voyages to the Jersey woods, one thing the four of them did together was go bowling. David bowled with “a natural grace,” said Doughton. “When he released the ball, it would touch the floor almost silently. He had a fair amount of power in his delivery too.”

Peter Hujar had begun to photograph certain of his friends and their “tribes” when he took David Wojnarowicz and Friends in 1985. From left: Steve Brown, Chuck Nanney, David, and Steve Doughton. Vintage gelatin-silver print, 20 × 16 inches. (© 1987 Peter Hujar Archive, LLC. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York)

They went to Hujar’s loft to pose on March 19. “He gave us no directions,” Doughton said, “and I remember feeling awkward. I think we all felt awkward.” A couple of days later Hujar called them over to see the print. “This is a shitty portrait,” he announced. “I’m trying to capture what you guys have, and it’s not there.” He began pulling out other pictures to illustrate what he meant. He had one of himself and three other photographers, jumping.

“Do you want us to jump?” asked Nanney.

“I want you to act like you know each other,” said Hujar. But he did not reshoot the picture.

Nanney ended up thinking it was funny, saying, “Instead of getting what he wanted, which was us exuding togetherness, he got the walls between us.”

Shortly before the Biennial opened, the first AIDS antibody test became available. Gay groups immediately announced their opposition to testing—until there could be guarantees of confidentiality. Not that the test would be easy to get in New York in any case. Other cities set up drop-in centers where the procedure could be done quickly and often anonymously. Other cities allowed physicians to use private labs. But under health commissioner David Sencer, New York had what many regarded as the most restrictive testing policy in the country—along with the most AIDS cases. The antibody test could be conducted “only by a city laboratory on referral from personal physicians” and it took months to get the results, reported the New York Times when the policy finally changed at the end of 1985. Sencer was the health commissioner who’d told reporters in February that there was no AIDS crisis, that no education about the disease was needed, that “the people of New York City who need to know already know all they need to know about AIDS.”

In her April 1985, East Village Eye column, “Dr.” Cookie Mueller answered a letter from a gay man who’d just broken up with his boyfriend and felt like a dinosaur at the bars. She told him it was OK to be more selective. “And don’t worry about AIDS, for God’s sake.… If you don’t have it now, you won’t get it. By now we’ve all been in some form of contact with it.… Not everybody gets it, only those predisposed to it. If everyone got it that was introduced to it, half the population of New York would be on death’s door by now.”

After a couple of negative letters came in, Cookie responded that she simply wanted to speak against paranoia and fear. “I’m sorry if I offended anyone.” At this point, no one knew how likely it was for someone infected with the virus to actually get AIDS, or how quickly that might happen. With health officials like Sencer in denial, ignorance was not Cookie’s fault, but it was her problem. She died of AIDS in 1989.

Newly ensconced at 155 Avenue B, Civilian Warfare managed to get a ten-thousand-dollar credit line from Citibank. “This poor bank officer probably lost his job over it,” Marisa Cardinale said. “He really believed in the East Village.” She was able to write checks at last—pay for the renovation, pay some artists, and pay rent until the end of ’84.

Operation Pressure Point had not yet pushed out the drug traffic, and Avenue B still qualified as the Wild East. So the typewriter they’d finally acquired was soon stolen. “Somebody unplugged it and walked out with it,” Alan Barrows remembered. “Somebody stole my jacket that had my keys in it. I had to change all the locks. Greer Lankton lost a sculpture that was in the gallery, a little baby. This couple came in with a baby carriage, and when they left, the mother was holding the baby in her arms and pushing the carriage out.” They realized later that the couple had put Greer’s sculpture in the baby carriage. Greer was devastated. She began wheat-pasting the neighborhood with flyers that said: “Sissy Baby Stolen. Reward.”

The January ’85 rent check bounced, and from then on, Civilian paid cash in bite-size payments. By spring it was $450 or $250 or $200 at a time.

In February ’85, Civilian sent David a check for $337.50—and it bounced. He may have eventually been paid. No one remembers. But in April, he dreamt that he’d fought with Barrows and Savard over the money they owed him. It was part of his only journal entry for 1985. He woke up angry, not remembering details except that at the end of the dream, he showed Barrows the IOU they’d given him. “It’s like some strange poetry,” David wrote. “Won’t stand up in court.”

The contrast at the gallery between Barrows and Savard grew sharper now as Savard’s drug addiction escalated, while Barrows, after experimenting, had stopped cold. At first, Marisa Cardinale recalled, Savard had just a “friendly” problem where, for example, he might pay her forty bucks he owed her, then ask for twenty back because he’d just “seen someone.” He’d disappear and come back, announcing that he now had two dime bags to share with her but he’d been shorted and he’d been charged “all that for just this.” So she knew he’d already used some of what he’d bought. And then he’d say, “Don’t tell Alan. It makes Alan crazy.”

For a while, Judy Glantzman lived upstairs from Savard and his boyfriend, Steve Adams. She remembered Savard knocking on her door sometimes “late at night and saying, ‘You know, I just need twenty dollars for’—and it would be something like ‘for eggs.’ ”

“Your work would get sold and you’d never hear about it,” said Bronson Eden, “because Dean would use the money to buy junk.”

“He was taking money from the gallery,” Barrows said. “He was taking checks out of the back of the book so we wouldn’t know there was money missing, and then the accounts wouldn’t jibe.” Usually that was small money, ten or twenty dollars. But then he started stealing things. For example, Barrows learned that Savard had stolen someone’s purse and was passing bad checks written on the purse owner’s checking account.

Barrows and his partner (also named Steve) had hired a friend of Savard’s to clean their apartment, not realizing that this woman, Martha, was actually Savard’s drug buddy. Barrows and Steve went out of town and returned to find that Martha and Savard had moved in. Savard was standing there in a necklace that Steve had inherited from his grandmother. He’d been stealing their clothes and their jewelry. Soon after they got Savard and Martha out, Barrows and Steve went to their local video store to rent a movie, only to be told that they had not returned that pile of porn movies they’d rented. Savard, of course, had used their account to get those films, then sold them. Barrows said of Savard: “It was like watching somebody become a vampire.”

Savard announced that he and Martha were going to Provincetown to clean up. Bronson Eden remembered the day Savard made his grand reentry at the gallery, declaring that he was now off drugs and everything would be different. This probably occurred around the beginning of April, when Eden and Steve Doughton had a two-man show at Civilian. At the opening, Martha came in and gave Eden a congratulatory hug. “As she was hugging me, this guy came in and put his hand on her shoulder,” Eden said. “It was a cop. She’d just bought heroin someplace, and he busted her right there in the gallery. The cat was out of the bag. Dean was still on drugs.”

When Barrows’s mother came to visit him at the beginning of May, he broke down crying one night and told her what was happening with Savard. She suggested getting his family involved. A couple of days later, they staged an intervention at Barrows’s apartment. Any focus on drug addiction got derailed, however, when Savard’s parents learned the (to them) startling news that Savard was gay. Barrows’s mother was the one who told them. She also declared that there was nothing wrong with it and that they should accept it. Barrows couldn’t remember how the topic even came up. He did remember Savard’s father announcing, “We are going to take the gay out of you,” and then driving Savard home to Connecticut.

The next issue of the East Village Eye reported, “Dean Savard is taking an extended vacation from his gallery to travel, relax, and work on his own art.”

That spring Judy Glantzman left Civilian for Gracie Mansion. She knew nothing of the intervention, but saw that “Dean was so far gone, it wasn’t going to get better.” She and David had been Civilian’s two biggest earners.

In April, photographer Timothy Greenfield-Sanders began inviting artists, dealers, and critics from the East Village scene to pose in a series of six group portraits he called The New Irascibles. He’d been out looking at art with his friend Robert Pincus-Witten and told him, now that the scene was so big, wouldn’t it be interesting to document the first generation of artists, the second generation, the first dealers, and so on. Pincus-Witten joked that such a project would become “the central document in the history of world culture.” They laughed, but Greenfield-Sanders followed through, and Pincus-Witten helped him make the lists.

For each grouping of twelve to fifteen people, Greenfield-Sanders used the same visual composition seen in Nina Leen’s historic 1950 portrait of the abstract expressionists, The Irascibles. Greenfield-Sanders’s pictures would run in Arts magazine with an article by Pincus-Witten describing how much in the scene had changed since 1983. David ended up in the cover shot—the first artists from the first galleries—with Judy Glantzman, Greer Lankton, Mike Bidlo (center, where Jackson Pollock sat in the original, assuming Pollock’s pose), Futura 2000, Mark Kostabi, Rodney Alan Greenblat, Luis Frangella, and others. Rick Prol overslept and missed the shoot, thus joining the “second generation,” and he told Greenfield-Sanders he would never forgive himself.

Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, The New Irascibles—Artists 1, 1985. Gelatin-silver print, 14 × 14 inches. Back row from left, after David: Futura 2000, Mark Kostabi, Craig Coleman, Greer Lankton. Second row from left: Judy Glantzman with knee up, Stephen Lack, Mike Bidlo, Luis Frangella, Arch Connelly, Rhonda Zwillinger. Seated at front, from left: Rodney Alan Greenblat, Joseph Nechtval, Richard Hambelton. (© Timothy Greenfield-Sanders 1985)

Everyone understood that history was being recorded here. Glantzman remembered the buzz around the scene about “who was going to make it into the pictures, and what cut would you make it into.” The rivalry, the jealousy—it was unpleasant, she thought, even nasty, and it was new. She and David were acquaintances at this point, not yet friends, but her feelings echo what David had confessed to Dennis Cooper around the time of the Biennial. “I remember 1985 as the end of the East Village,” Glantzman said. “The whole thing had broken down.”

Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, The New Irascibles—Dealers 1, 1985. Gelatin-silver print, 14 × 14 inches. Back row from left: Alan Barrows, cut-out of Dean Savard, Rich Colicchio, Gracie Mansion. Second row from left: Elizabeth McDonald, Bill Stelling, Sur Rodney Sur, Mario Fernandez, Peter Nagy. Front row from left: Doug Milford with knee up, Patti Astor, Nina Siegenfeld, Alan Belcher. (© Timothy Greenfield-Sanders 1985)

“What was ending was the intimacy,” Greenfield-Sanders said, “the sense that everyone knew everyone else.” New galleries were still popping up in old storefronts, but they were not there to present a wry commentary on the art world. They were the art world, and they had swallowed the art playground.

Greenfield-Sanders asked Glantzman to bring in the wood cutout she’d made of Dean Savard. (She had just done a show at Steve Adams Gallery called “Glantzman Cuts Up Her Friends,” sixty-six cutouts of artists, critics, and collectors at three-quarters lifesize.) That got Savard into the photo of “first dealers.” Just so, one of Nicolas Moufarrege’s embroidery pieces represented him in the critics’ portrait. For a couple of months, he had been in the hospital and was said to be suffering from “a terrible pneumonia.” It was Pneumocystis.

Moufarrege’s death from AIDS on June 4 sent a shock wave through the community. I spoke to people who hadn’t known him personally who could still recall just where they were when they heard the news.

For some reason, he’d been hospitalized in the northern end of the Bronx, far from his friends. Nevertheless, David did go to visit. This would have been his first look at what it could mean to be sick with AIDS. Chuck Nanney also visited, though he and Moufarrege had broken up more than a year earlier. The breakup was so bad they wouldn’t speak when they ran into each other on the street or at openings. So Nanney made the trip with some apprehension, but Moufarrege clearly had no memory of whatever had gone wrong between them. He had Kaposi’s lesions on his face and some form of dementia. He actually seemed happy, Nanney remembered. “He was able to respond, but then part of his conversation would be all nonsensical, and then he would apologize for it and—it was so hard.”

Hospital staff would come in “practically wearing hazmat suits,” said Nanney. “The nurses didn’t want to be around him. They didn’t want to touch him.”

Myths about how the disease was transmitted would persist for years. Along with fear. Along with stigma. Moufarrege’s obituary in the New York Times said he died of pneumonia.

Hujar was closer to Moufarrege than David was, so he must have gone to visit him as well, but that’s conjecture. Nor can we know what inspired Hujar and then David to see a nutritionist that spring. But in those days, diet was one of the few ways anyone could think of to combat the disease if they had it—or to keep from getting it if they didn’t. That spring they both began what Hujar, in a phone message to David, called a “lymph fast.”

This may have had nothing to do with AIDS, however. (David told a few people that spring that he’d been tested for what was still called HTLV-III and was negative, though as previously noted, it was not yet easy to get such a test.) He was unhappy enough to be looking for a major life change. In a couple of handwritten pages found among his papers, he wrote, “I feel lonely and … fear that I am totally unlike other people, that I haven’t the ability to trust them completely … that I am emotionally drifting further away from myself and my abilities to show emotion. I think that I am unloved … and the longer I am not in a relationship the further I am cut off from emotions and I want to be with people but I cut myself off from people … and never let anyone near except for Peter and I think if he were not there I would go crazy.”

But the day he wrote that, he’d awakened with such wonder from a dream in which he could fly. Now he felt that he was beginning “to get out from under the havoc and meanness I see in people in the art scene. Something from my conversation with Peter yesterday when he showed me my qualities—that unlocked the beginning of change. The cigarettes etc are what I need to stop in order to keep the change stronger.”

By the beginning of May, David was at work on an installation in the Anchorage beneath the Brooklyn Bridge. He was one of fourteen artists selected to show that summer (from two hundred applicants) by Creative Time, an organization that brings art into public spaces. Until the city shut it down for national security reasons in 2002, the Anchorage was one of the most spectacular spaces an artist could hope to work in. The fifty-foot-tall vaulted ceilings, stone floors, windowless brick, and overhead traffic hum made for an ambience that could be all gothic gloom or cool cave, dungeon or cathedral, depending on the art.

David’s piece was installed in one of the “most confined and sinister spaces,” according to the brochure handed out for that year’s Art in the Anchorage. Here he created a cannibal tableau, a family dinner in hell. Two skeletons sit at either end of a long table. One of them, painted red, applies bare wires from a radio to a yellow skeleton stretched before it. The other skeleton looks blue but is at least partly covered with maps. This one has a blue baby doll raised to its mouth. Blood drips down the torn tablecloth. There’s a centerpiece of burnt wood; around it, debris, half-drunk glasses of wine and a bottle of Night Train (with Ronald Reagan’s face on the label). Dry leaves and other detritus litter the floor. Behind the blue skeleton there’s a roadside scrum of weeds, old tires, and another skeleton at least partly covered in maps. This one is seated in one of the tires, a globe between its knees and a gun in its mouth.

David hired his friends Steve Doughton and Philip Zimmerman to help him create what he simply called Installation #5. (They gathered garbage and painted the skeletons.) He never talked to them about what the piece meant, but it’s rather crudely apparent. The predatory parents. The alcohol, burning, and blood. The waste surrounding it all. Suspended over the center of the dinner table is the skeleton of a child, ascending into heaven in a white dress and a garland of flowers. “She appears unusually pure and un-mutilated compared to the other child skeletons,” wrote Mina Roustayi, the one critic or journalist who spoke to David about what the thing meant. Roustayi told David that she thought Installation #5 related to “the global nature of problems like greed, nuclear war, child abuse, and the instinct for self-extinction.” That was valid, he told her, but in fact he’d based the piece “on his childhood and life experience.”

That month, Life magazine published a feature on East Village art with a photo of David spread over two pages. He’d staged this picture months earlier, setting up at dusk in one of Alphabet City’s many vacant lots, this one with low hills of dirt and the usual garbage. Marion Scemama knew someone with a truck, and they’d carted the elephant skeleton, a human skeleton, a burning child, and a few cow skulls covered with maps to this location, then lit a fire in a wire trash receptacle. Marion thought the magazine chose “the most stupid photo. He’s sitting there painting a skull.”

In New Jersey that month, Steven Wojnarowicz’s wife, Karen, happened to see the magazine and showed it to Steven, who learned then that his brother had become an artist of some renown. Steven managed to track David down by phone. When David learned that his brother was working for the American Automobile Association, he told Steven that he sometimes used maps in his work. Could Steven get him some maps? Yes. He could. It was the first time they’d spoken since their father’s funeral, eight and a half years earlier.

They arranged to meet at a restaurant on Forty-second Street. “I remember sitting down to talk to him, and David said, ‘You don’t know I was a child prostitute.’ He was hitting me with everything, trying to see if he could just turn me away,” Steven remembered. “And I said, ‘Well, that’s OK. I still love you. You’re my brother.’ ”

Sometime around May 22, David left town in the Malibu. He gave up the apartment on Fourth Street and told Tom Cochran, who still held the lease, that he didn’t know if he was coming back to New York. Most startling, he left without telling Hujar.

“He disappeared,” John Erdman said. “I saw Peter a lot, and he was always wondering where David was, wondering what it meant, wondering if he was going to come back. He wasn’t angry. He was never angry at David, ever, about anything. I remember Peter talking about it and I remember thinking, poor David. He really had to do something to get out from under Peter’s thumb. Peter was controlling him or trying to like crazy. He saw him as an offspring and he wanted him to do what he wanted him to do. You saw David getting quieter and quieter. You saw him pulling in and withdrawing. At the same time, you could see that he adored Peter but didn’t know what to do. I don’t think they had any specific fight. David just had to get out of there. He had to get out from under Peter.”

David intended to spend the summer on the road with Steve Dough-ton and Philip Zimmerman, the friends who’d helped him at the Anchorage. “We had this romantic idea of moving to New Mexico,” Doughton said. Not to live together but maybe to live near each other.

Doughton and Zimmerman were also artists interested, like David, in tough elemental and mythic imagery. Doughton sculpted figures from wood, human blood, excrement, and semen. He thought that both he and David had been much influenced by Zimmerman, whose work Doughton described as “devotional, sometimes made out of his own blood and found objects.” Zimmerman worked with alchemical, magical, and religious symbolism and had created, for example, many paintings of figures on fire. Invited at one point to show his work to a curator at a New York museum, Zimmerman unfurled a painting of a life-size devil standing in flames with the inverted heads of Lincoln, Washington, and Kennedy at the devil’s feet like glowing coals, and a burning church atop the devil’s levitating head. “I got thrown out of the curator’s office,” said Zimmerman. David liked that. He thought it was funny. In 1984–85, Zimmerman was making tiny paintings out of bug parts, fingernails, cat whiskers, gold, paint, dried bats, bones, human blood, spiderwebs, dried bread, and dust. He and David would discuss, for example, the symbolism found in existing belief systems like voodoo or Santeria and how an artist could, in Zimmerman’s words, “articulate an internal paradigm but use symbols from older traditions.” All three of them collected objects like animal skulls, but also traded them and gifted them.

Their plan was to head for the Southwest, where David wanted to visit the Hopi village of Oraibi, Arizona. Then they’d drive up the west coast and loop into the northern plains, stopping at Yellowstone. First, though, they would travel to Louisiana to visit Steve Brown, who had planned to join them on this summerlong trip until he got a job on a film called Belizaire the Cajun.

The trip was an utter debacle. Doughton said later that he and Zimmerman should have seen it from day one, when David came to pick them up and said, “What the fuck!” as they brought out boxes of books they were going to read and sculptures Doughton was taking to a show in Portland. “He made us haul half the stuff back,” Doughton recalled. “Then we get to his house and he’s bringing just as much as we had, including a typewriter. This car is just loaded to the gills. We’re all making sculptures, and we’re going to be doing art on the road, so we need our materials. It was just absurd.”

Nothing practical had been thought out. Doughton and Zimmerman each had about $120 to their name. Even more ominous was the news that David was still following his new diet and had decided that the trip would give him a good chance to detox. “We start this road trip,” Doughton said, “and David is all of a sudden a vegan, not smoking, not drinking coffee, not drinking beer, not eating sugar, and he’s just being a real asshole.” David’s true drugs of choice were caffeine and nicotine, his favorite dinner was steak, and he sometimes seemed to be living on candy bars. Now he was headed across the country drinking spirulina and a barley grass supplement called green magma.

Something again seemed to be cracking inside him. He’d behaved terribly in April when Steve Brown left for Louisiana and his film job. David and Doughton had helped Brown with last-minute errands before he caught his train at Penn Station. Brown was in a foul anxious mood, and David spent the day needling him. Doughton thought it was because the two had had a brief affair: “David really loved Steve Brown. And the feelings were not returned.” So, as they ran their errands, David elbowed Brown and raised his eyebrows every time they passed a guy, like, “there’s a hottie for ya.” Brown told him to knock it off, so David did it more, with any male they passed—child, old man, or bum. “There’s one for ya.” Brown begged him to stop. David simply switched to something more irritating. He pulled out a black permanent marker and started writing “For a good time call Steve” or “I love cock! Ask for Steve” with Brown’s real phone number—tagging every surface they passed, from signs to parking meters, while Brown threw fits. Finally Brown became hysterical and started crying, and Doughton asked David to stop.

David stopped. They got to the train platform and helped Brown load his luggage on board. He had reserved a little compartment for himself with a foldout bed and a small desk. He talked about how he was looking forward to watching the landscape roll by while he worked on a script. He apologized for overreacting, after David apologized for writing the graffiti. David and Doughton then went outside to wave goodbye. The train began to inch away. Brown had his face up to the window blowing kisses. Suddenly, David whipped out the marker and wrote “QUEER” on Brown’s window in huge letters. Said Doughton: “I’ll never forget the image of Steve jumping up and down in his little room, veins bulging in his purple face, and the sound of his muffled screams as the train disappeared down the tracks.” David was doubled over, laughing.

That was the prelude to a full summer of blowups between David and his friends. Doughton, though, said, “We were not battling 24-7. Many of our experiences were great and among the best of my life.” They camped in the Blue Ridge Mountains, visited the shore near Virginia Beach, and one day, driving west of Richmond, spotted a bottle tree. They backed up to take a look at the dead tree festooned with bottles on its branches, driving up to a house on a bit of a rise. This turned out to be a highlight of that summer. An old man came outside. They told him they were artists and had noticed his tree. He then invited them into his house and showed them his own amazing work. Zimmerman said the man had taken “dolls with pink plastic flesh and long blonde nylon hair and given them new faces made out of sawdust and Elmer’s glue. So the figures had dark crude and crusty faces with a shock of flaxen blonde hair coming out of the top. Others were robust women carved in wood from pieced boards with these same crusty sawdust and glue faces. They had teapot lids for hats. He also made animals out of logs and stuck real antlers on them.” David bought one of his deer. Doughton and Zimmerman each bought one of the woman sculptures. The man had signed each of the figures: AbeL Criss. They found out later that he was a rather well-known folk artist, Abraham Lincoln Criss. He was selling his pieces for about twenty dollars each.

They meandered on toward their rendezvous with Steve Brown in Louisiana, dipping into Alabama and north into Tennessee, visiting Graceland and Loretta Lynn’s country store and a rattlesnake exhibit set up in cages along the side of the road. But what stood out in both Doughton’s and Zimmerman’s memories was their growing friction with David. He criticized their driving when he himself was none too good behind the wheel, in Doughton’s opinion. David never looked more than twenty or thirty feet ahead, so he was always slamming on the brakes or swerving at the last minute. He stopped constantly to take pictures of roadkill, no matter the situation. “He’d cross three lanes of freeway to photograph a dead animal,” Doughton said. Also, David always drove with the windows open, even when it rained, because, Doughton observed, “he hated having glass between him and the world. He hated being in a bubble.” But these were endurable irritations. The real tension began when they stopped for the night. David grew increasingly angry because Doughton and Zimmerman would refuse to undress in front of him.

Philip Zimmerman (left) and Steve Doughton in the only photo David took of them together during the rancorous cross-country trip in summer 1985. (David Wojnarowicz Papers, Fales Library, NYU)

This was not about sex. “He thought we were having a secret life apart from him,” Zimmerman explained. Doughton is straight and Zimmerman is gay. They were roommates and best friends, but never undressed in front of each other either. Still, Zimmerman thought, they were about as intimate as a straight man and a gay man could ever be. “We were almost symbiotic,” he said. “It is hard to explain, but we had an understanding about each other and a connection that David was jealous of.”

They got to Lafayette, Louisiana, at the beginning of June. Steve Brown was happy to see them, though he acted a little miffed at first over David’s prank. Lafayette is on the western rim of the Atchafalaya Swamp, where they spent a few days trying to find alligators—and restaurants that served gator steaks. (They found none.) David still wasn’t officially eating meat, but he hadn’t lasted long as a vegan. One of their first nights on the road, they’d stopped at an all-you-can-eat seafood buffet and David packed away three plates of crab. In Lafayette, they went to what was probably a wrap party for the movie and feasted on crawdads.

One day they went into the Atchafalaya with a guide. Zimmerman said, “David was in heaven, looking for alligators and water moccasins. He just had amazing empathy for animals and their innocence. His best stories were about innocent creatures who were tormented by their owners, then rescued by [someone who] would give the evil humans their comeuppance” David identified with such animals. He took photos in the swamp, but they found no alligators and finally had to go to a gator farm to see some.

One night they went to a Black Flag concert and were astonished to see a drag queen walk into the roiling crowd of slam dancers. When some muscular jock pushed the queen to the floor, Brown yelled, “Let’s get him!” Doughton recalled that Brown punched the jock while feeling him up until a bouncer pried them apart and that “David was laughing hysterically and snapping photos.” For years after, David would not show them the pictures. When he finally did, they saw that these were not vacation snapshots, not a record of friends’ antics. David had framed most of the photos to show just legs and torsos, to make people unidentifiable. “He reduced this wild experience to anonymous sweaty male bodies in some bizarre state of rage and ecstasy,” Doughton said. Even then, David was making his art. A few years later, one of these photos ended up in a piece called Spirituality (for Paul Thek).

Before they left Lafayette, David and Steve Brown had another fight. Doughton thought it had to do with “David feeling that his love for Steve was one-sided. According to Steve, David said, ‘The only way you’d love me is if I were a cold son-of-a-bitch.’ ”

They were in Texas when David gave them the heave-ho. Neither Doughton nor Zimmerman could remember what finally pushed David over the edge or even what city they were in when he drove them to the bus station and announced, fuck you, you’re getting out here.

They’d had a terrible blowup at the hotel in Lafayette. “I don’t remember the cause of it, but David was angry with all three of us and stormed out of the room,” said Doughton. “The three of us sat there trying to figure out what was eating him. I suggested that it wasn’t us, that it was unresolved anger about something from his past. Suddenly the door burst open. David had been listening. He rushed in shouting at me, ‘You wanna know what it is? It’s you. You’re selfish. It’s you and your selfishness!’ ”

Zimmerman and Brown left the room so Doughton could hash it out with David. But Doughton couldn’t remember David giving him any examples of his selfishness. Nothing was resolved. “At one point, I decided that I wanted to nail him so I told him that he reminded me of my father,” Doughton said. “It was a low blow, and I knew it. Later, in the fall when we patched it up, he told me that those words hurt and asked me if I meant them. It’s not that my father was a bad guy. David had met him and liked him. He said he just hated to have his faults compared to those of any father.”

Soon after they crossed the state line into Texas, David was driving up a long incline when he suddenly swerved onto the shoulder. “Steve [Dough-ton] and I started to giggle,” Zimmerman said, “because David had just lambasted us for our poor driving skills. He got so enraged—I was sitting in the back—and when he turned around to snarl at me, I almost didn’t recognize him. His face had turned purple, and his eyes were bugging out. It was actually scary.”

When they parted at the bus station in San Antonio or Dallas or wherever it was, Doughton and Zimmerman were relieved. “David was tough to be around,” Doughton recalled. “The rage he was going through at that point was just incredible.”

Doughton bought a ticket for Portland and had a dollar left. “I spent it on a bag of sunflower seeds.”

David drove on alone toward Albuquerque. Once there, he sent the first of two postcards to Hujar, and their wording suggests that he had already been in touch by phone, that Hujar knew who he was traveling with. “Me and the guys split up in different directions,” wrote David. “I guess it was for the best.… I’m too wound up crazy to travel with them.”

David called Keith Davis to tell him that he’d jettisoned Doughton and Zimmerman—“such jerks.” Would Keith like to fly out to meet him? They could travel the Southwest together and head up the coast. Keith thought that sounded great. By mid-June he had joined David in the desert. From the time they’d first met, Keith had been very attached to David. They’d also had an affair at some point, though that may have been very brief. Keith was having a tough year. He’d ended a long-term relationship, and his business was in trouble. He’d started Swimming Pool Productions with the goal of bringing fine artists into his graphic design practice. For example, he hired Hujar to photograph ads for a high-end clothing store called Dianne B. (Hujar had used David as his model wherever it was appropriate: David shirtless and wrapped in a luscious blanket. David in the sort of white shirt he would never wear in real life. And so on.) Keith put David’s gagging cow at the pier on the back of an Evan Lurie album. And he was designing Nan Goldin’s celebrated first book, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. Keith had started the year hoping he’d make enough money to pay off his mortgage. By October, he would declare the enterprise a failure.

Keith Davis with souvenirs, most of them probably David’s, during the cross-country trip in summer 1985. (David Wojnarowicz Papers, Fales Library, NYU)

David’s contact sheets from this leg of the journey show him and Keith in Monument Valley and in Death Valley. “We made it alive through Death Valley,” David wrote in his next postcard to Hujar. “Peter I feel crazy but I think of you and hope I can work this all out—my problems and such. Love you. Ciao, David.” He continued to photograph roadkill along with his Western obsessions, like kachina dolls and newspaper stories about snake injuries. In his pictures, he and Keith reach the coast and the forests, and whatever has gone awry between them by the time they got to Oregon does not show.

Keith was good friends with both Zimmerman and Doughton. They were all Oregonians. Keith told Doughton later that David had been “flying into fits of rage.” But the tension all came to a head when Keith and David stopped to spend the night with Zimmerman at his parents’ house in a town southeast of Portland. (Zimmerman said he and David were “OK” at that point, or enough OK that he could have them spend the night, but he sensed tension between David and Keith.) “My parents had only one extra room,” Zimmerman said, “and Keith and David weren’t going to sleep in the same room, probably because they’d been fighting. My parents have this awful sofa bed in a room full of spiders. Keith got the good room, and David had to sleep on the spider bed. He was furious about that.”

As soon as Keith and David arrived in Portland the next day, Keith got out of the Malibu and didn’t look back. He called Doughton.

“I get this phone call from Keith,” said Doughton. “He’s like, ‘I’ve been driving with David, and he’s such a fucking asshole.’ ”

“I said, ‘Tell me about it. I hate him.’ ”

“And Keith said, ‘I do too. I hate him.’ ”

David drove back to Albuquerque alone and spent at least a week there. The Malibu needed repairs. He called Richard Kern and Tommy Turner to tell them that he’d separated from some other friends who were jerks. Would they like to join him on a trip through the South? They thought that sounded like fun.

David met Kern and Turner and Turner’s wife, Amy, at the Memphis airport. All three of them were using heroin, and Kern admitted to being dope sick for the duration—probably about ten days. He remembered going to Graceland, David’s second visit of that summer to Elvis’s grave, and then going to Charleston, South Carolina, at a time of flooding. Receipts indicate that they overnighted at a truck stop in Georgia and visited the Outer Banks.

At some point between Portland and Memphis, David had given up his self-imposed diet restrictions and gone back to coffee, cigarettes, red meat, and sugar. That may have helped to smooth some jagged edges. But, years later, what Kern remembered most about this trip was David’s anger.

David paid for all the hotel rooms, so they always got one room with two double beds. Tommy and Amy Turner took one. David thought he and Kern should share the other. Kern told him, “I’m not sleeping with you, dude. I’ll be laying there feeling weird all night, so I’ll sleep on the floor.” Kern suggested they take turns. The next night, David could take the floor. “After a couple days of this,” Kern said, “we’re sitting in the car, and David’s like”—Kern made a huffing sound—“just like in the movie.” Meaning Stray Dogs, where the David character rages silently until he literally explodes.

Their last stop was Washington, D.C. David went off to the Smithsonian with Turner, and they arranged to meet Kern later. Without telling them what he planned, Kern went directly to Union Station and caught a train to New York. David and Turner waited an hour. According to Turner, David was relieved when Kern didn’t show up. Later, David remembered his travels with Kern and the Turners as the good part of his summer.

He got back to New York on August 2 and went to see Keith Davis, an encounter Keith then wrote up in his journal: “I knew [David] would have to call me to get his check book. But I had no idea he would still be full of the shit I experienced out west. More of the line about me sharing responsibility for what happened.… He said that he will be spending less time with art world people like Philip [Zimmerman], Steve [Doughton] and me. And that there were no problems with Richard Kern, Tommy or Amy so there must be something wrong with us—Steve, Philip, Keith. Real shit. I couldn’t even respond. Fuck him.” Later that day, he added, “I don’t feel any sadness for David. I wish he were dead.”

The strictures against “art world people” did not apply to Hujar. On August 7, David sent him a postcard: “Dear Peter, It’s time to get together.”