On New Year’s Day 1986, Tom Rauffenbart drank champagne all day while he cooked suckling pig, collard greens, and black-eyed peas for dozens of friends. It was probably eleven thirty or twelve that night when he left his apartment, wired and drunk, to walk to the Bijou, a porn theater on Third Avenue near Thirteenth Street. And there he saw that guy again, the guy he’d described to a friend as so ugly he was beautiful.

He was Tom’s type, tall and lean with a long face and buckteeth. Tom had encountered him at the Bijou sometime in November ’85, and they’d had sex in a bathroom. “Sometimes you can do that and it’s awful,” Tom said, “but with him it was so sexy.” Though they hadn’t talked much, Tom had mentioned that he’d lived in the East Village since the sixties, and then he heard that startlingly deep voice for the first time: “You must have seen a lot of changes.” They did not exchange names.

When Tom saw him again on New Year’s, he thought maybe the guy wouldn’t be interested again. But he was, and they went into the same little bathroom and began to have sex when Tom asked, as he rarely ever did, “Want to go to my house?” Out on the street, they said their names.

“Tom.”

“David.”

As they walked to Tom’s place on East Ninth, they told each other what they did. David said he was a painter.

Tom replied, “Oh. A house painter?”

David seemed bemused. Tom didn’t know a thing about art, and he’d ignored the galleries popping up around him in the East Village. Ironically enough, he worked for the city’s child welfare department, where he’d spent ten years “in the field,” going to allegedly abusive homes and deciding on the spot whether to take the children out with him. By the time he met David, he was in management.

“We spent the night together, which was really erotic and wonderful,” Tom said. “I invited him to stay over, and he said, thanks, because he was living in a place where there were a lot of junkies around and it wasn’t that comfortable walking home. This was unusual. I rarely invited someone to stay. I usually wanted them out.

“I remember waking up the next morning. I had to go to work, and I just kept looking at him in bed. I was filled with all this emotion. I made a cup of coffee and stood in the doorway watching him sleep, just thinking how wonderful this guy looked and just being really moved. I hadn’t been moved by anybody in quite a long time, but this guy really touched something in me, and I don’t know what it was. I could just feel this electricity going on. And I just wanted to touch everything that touched him. I’d never done anything like this before but—I smelled his shoes.”

Later that day, January 2, Peter Hujar’s show opened at the Gracie Mansion Gallery. David had insisted on this, and Gracie agreed despite Hujar’s reputation in the art world as “difficult.”

A couple of years before this, Timothy Greathouse had offered to show Hujar’s work with Nan Goldin’s, when she was not yet famous. Greathouse then canceled Goldin to give Hujar a solo show, and Hujar canceled out of loyalty to Goldin.

So he had not had a solo show in New York since 1981.

“The rumor was that Peter hated all his dealers,” Gracie said, “that he was worse than David, that he was impossible to work with.” But this time, everything clicked. According to Gracie, “Peter was a sweetheart.”

Hujar’s old friends, Gary Schneider and John Erdman, remembered how happy he was. “He was totally in awe of Gracie,” Schneider said. “He thought she was this brilliant light in the East Village.” Erdman added, “He thought Gracie was enormously glamorous, and he was shocked that she would do a show of his.”

Gracie turned the practical matters over to Sur Rodney Sur, who had a particular knowledge of and interest in photography. Sur asked Hujar what he wanted.

To show a hundred photographs.

Sur told him to bring them in and lay them out, and they’d do it. “We pretty much said, ‘Do what you want, and we’ll make it happen.’ ”

Sur explained, “I installed our shows, but I said, ‘I’m not going to hang a hundred photographs behind glass, all perfectly neat.’ So we hired a very expensive art installer who installed for Pat Hearn, and they did the whole thing beautifully. It was laid out exactly the way Peter wanted, and he was thrilled. Totally thrilled. Because he got the show to look the way he wanted. And I think we sold two prints out of that show. They were six hundred dollars apiece, and no one would buy them.”p

In the opinion of Gary Schneider, this was Hujar’s best show, and though no one knew it at the time, it was also his last show. Gracie had basically given him a retrospective, and she paired him, in her back room, with Al Hansen, an important Fluxus artist from Hujar’s generation and someone Gracie had known for years.

In another decade, another season, the show would have been regarded as an event, but in 1986, the art world ignored it.

The one exception was Village Voice critic Gary Indiana, who wrote a piece called “The No Name Review,” in which he discussed several exhibitions without naming a single artist. As Indiana explained, “Open a fucking art magazine and there’s one proper name after another after another. The proper names just start to stand in for whatever it is you’re looking at. Everybody becomes a brand in the art world. It was something that was particularly bothering me at the time.”

Given that whatever hurt Hujar would hurt David, the two of them probably saw Gary’s review as revenge for David’s East Village Eye piece, which was still on newsstands as this show opened. Maybe Hujar was even thankful not to be named, since his portraits were described as “those serene, elegant, haunting views of dead people and living people who look dead.” Even his pictures of animals were maligned. Gary quoted someone he calls “N” who evokes Alfred Eisenstaedt’s portrait of Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels and claims that most of the people photographed by Hujar looked like Goebbels. “So did the duck. So did the dog.”

Tom called David on January 3 and they decided on a first date. They would drive to Robert Moses State Park on the western end of Fire Island. Tom got his first look at the beat-up Malibu, with its saints and monsters on the dashboard and, at this point, two cat skeletons in the back.

They walked the beach in the bitter cold, and David picked up a bird wing. It was a friend’s favorite image, he said, without mentioning the friend’s name: Peter Hujar. Then he picked up some metal bits. “For my rust collection,” he explained, while Tom thought but didn’t say, “What?” They drove on to a marina, where they sat outside drinking coffee, and Tom confessed to the most violent—and most uncharacteristic—moment of his life. After eleven awful months with his first boyfriend, Tom snapped into such a fury one day that he blacked out, and when he came to, he was pounding his boyfriend’s head on the floor. David would later tell Tom that he had wondered then if he was getting involved with a psycho. They were still strangers, but felt enough of a connection to begin forging past the unexpected and mysterious in each other.

For the next two or three weeks, David came to Tom’s place almost every night. “I was totally crazy about him,” Tom remembered. “I was just so emotionally moved by this guy. And erotically. It was wonderful, terrific sex. It was great being around him too. And I’d be crazy at work all the time. I couldn’t stop talking about him.”

David began to sort out his own feelings as he wrote his fourth and final piece for the East Village Eye:

Walking back and forth from room to room, trailing bluish shadows, I feel weak; something turning emotional and wild and forming a crazy knot in the deep part of the stomach. And on the next trip from the front of the apartment to the back I end up in the kitchen turning once again and suddenly sinking down to the floor in a crouching position against the wall and side of the stove in a blaze of wintery sunlight; it’s blinding me as my fingers trace small circles through the hair on the sides of my temples, and I’ve had little sleep, having woken up a number of times slightly shocked at the sense of another guy’s warm skin and my hands having been moving independent of me in sleep; tracing the lines of his arms and belly and hips and side.… So here I am heading out into cold winds of the canyon streets walking down and across Avenue C towards my home with the smell and taste of him wrapped around my neck and jaw like some scarf.

David did not tell Tom he was writing this. Nor did he show it to him. Tom found it by chance when he picked up a copy of the Eye. He could not remember what they then said to each other. Probably little. While David found it easy to rage at someone, positive feelings were not only hard for him to articulate but also frightening.

He went to talk to Karen Finley about Tom. “He was scared about his feelings and what to do about them,” she said. “I think he was afraid of love because what he had experienced as love from his parents was abuse. With a human who’s been damaged by inappropriate sexuality and the power of abuse—we know that the human psyche becomes schizoid and splits, and he would do that. But I told him he was nuts if he walked away from Tom.” She encouraged him to tell Tom his fears.

During the last week of January, David called Tom at work, said he had to see him and wouldn’t say why. “I immediately thought, well, he wants to break up,” Tom said. They arranged to meet at Veselka, a Ukrainian place on Second Avenue. “David came in and he was just a nervous wreck,” said Tom. “I’d never seen him like that. And I don’t remember exactly how he put it, but the message was that he was really scared. He had all these feelings he didn’t know what to do with, all this churning, and he felt lost. I remember being so relieved. Like, is that all? And I said, ‘We can take it slow, because I’m confused too. There’s so much emotion going on here, I don’t know what I’m doing either.’ And I remember he went, ‘Oh. OK.’ Of course, we immediately went to my house and fucked.”

David’s account of this appeared in a letter he wrote to Luis Frangella in Argentina. After years of not allowing himself to get into a relationship, he wrote, he’d let himself go and now he’d just talked to the guy in a restaurant “and he said something about not seeing each other so much.” That was David’s version of “We can take it slow.”

By the end of January, David had moved into a fifth-floor walk-up in Richard Kern’s building at 529 East Thirteenth. He had declined Tom’s offer to help, saying he had friends who could do the hauling. This was the beginning of a pattern. David would keep Tom separate from nearly everyone he knew.

As Tom once described the contrast between himself and David’s boho friends: “I was settled, I cooked, I had furniture.” He wasn’t just being facetious. Tom had never gone to the Second Street apartment. But on a first visit to Thirteenth Street, he saw that David had a couple of hardback chairs, a futon on the floor, paint, clutter, and a baby elephant skeleton. “Nothing comfortable anywhere,” Tom remembered. And he told David, “You have to buy a bed.”

Like Jean Pierre, Tom was middle class and utterly dependable. He was nine years older than David. He loved cooking and the comforts of home. “David met me at an opportune time for him,” Tom said. “He thought his career might be dead, and he was fed up with the world he had been in, and in a sense, he hid away with me.”

They decided to go to Montreal together the last weekend of January. Tom had always wanted to go there in the winter. So on the appointed Friday morning, he went to Grand Central and bought their tickets and waited. David never showed up. He’d gone to Penn Station. They didn’t reconnect until lunch at an East Village sushi bar, and David offered to pay for airline tickets to Montreal. Then they looked at each other and said, “We’re crazy. Let’s go to the Caribbean.”

Neither of them had ever been there. They went to Tom’s house, called an airline, and asked the ticket agent, “What’s a good place in the Caribbean?” So began their improvised odyssey to the Virgin Islands. From a guidebook bought at the airport, they settled on St. John’s as a final destination. The trip became a honeymoon, and nothing could destroy the glow or the afterglow. Not the wait in San Juan’s airport from three A.M. to six for the flight to St. Thomas. Not Tom learning to drive stick shift on St. John’s as they climbed hairpin turns up a mountain in a rented Jeep. Not learning that the room they’d reserved was unavailable. They loved the inn they found by chance. They abjured the chichi restaurants for great local cooking. They had sex on various beaches and in the ocean. At night they could lie on the sand and see a million stars. It was so romantic.

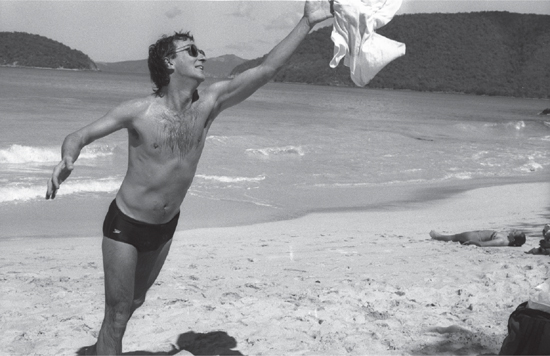

Tom Rauffenbart photographed by David on the beach at St. John’s. (David Wojnarowicz Papers, Fales Library, NYU)

They amazed each other with how public they were, having sex not just on the beach behind some rocks but also in the minivan driving them back to the airport, where they jerked each other off in the back seat. “We were just so aroused. We were outrageous,” Tom said. They didn’t change out of their bathing suits till they got back to San Juan, where they were still walking around with big erections. Someone came up to them and said, “You guys were the scandal of the St. Thomas airport.” They waited for their flight back to New York in a coffee shop, where Tom said to David, “I’m falling in love with you,” and David said nothing. His eyes filled with tears and turned red. He looked away.

“It was fine with me, that response,” said Tom. “I just remember his whole face went into shock.” They boarded their plane. Both liked aisle seats, so David sat in front of Tom. During the flight, David reached his hand back. Tom grabbed it. They held hands.

David wanted to paint again. He did not mention that he’d devoted a year to “imperiled child” or “dead family” scenarios when he explained his hiatus from painting to the New Art Examiner. “The attention and money for me was getting in the way of any kind of clarity, and I needed to pull away,” he said. “All of this media stuff, you get lost in it. You can take it too seriously and become self-conscious. It seemed like a joke at a certain point. People just come into the gallery and take what you put out and they don’t even look at it. You just become a workhorse filling a list. You self-imitate to meet demand.” His main journal for 1986 is all sketches, lists, and ideas for paintings. He seemed infused with a new confidence and focus.

Early that year, he began preparing for an April show at Gracie Mansion he would call “An Exploration of the History of Collisions in Reverse.” David was beginning his mature work here. There would be no more stenciling on a poster, though the title of a painting he’d done in 1984, Soon All This Will Be Picturesque Ruins, still functioned as a theme. That painting was simple, even crude, however, while the new work was dense and multilayered, loaded with messages and storylines about a civilization hurtling toward apocalypse.

Crash: The Birth of Language/The Invention of Lies is emblematic, its central image a steam locomotive that is about to collide with a very small planet Earth. Parts of the train are cut away, and the biggest scene visible inside it, the focus of the whole painting, is a dead human tied facedown in the desert and now serving as carrion for two vultures. References to his own past work are embedded throughout—a floating alien head, a burning building, a ground of supermarket posters visible in bits behind the train. In front of the locomotive, above planet Earth, is a skeleton with a lizard head and possibly a human body. Letters of the alphabet explode above that head but form no words. There’s more, but that describes the major “action.”

David would have been able to say what every single image meant to him. Nothing in his paintings was ever arbitrary, nothing was by chance. The train, in his cosmology, symbolized the acceleration of time. He chose that—over, say, airplanes—because trains were the instrument of westward expansion; they had wiped out a culture. (A pueblo and a kachina are visible inside one of the locomotive’s wheels.) In another of these “history paintings,” Some Things from Sleep: For Jane and Charley, the side of a locomotive is cut away to reveal a baby, floating in water and still tethered to its umbilical cord. Jane Dickson and Charley Ahearn were about to have a baby, and Dickson described David as “enthusiastic” about that. But in David’s view, each new human joins the collision course humanity is on.

The “history paintings” seem to follow naturally out of the Mnuchin installation, down to the gray pile of debris, mostly old machinery, that dominates Excavating the Temples of the New Gods. One image in this painting is a head of Christ with crown of thorns, made to look like one of David’s “alien heads,” green and floating over a background of paper currency. Corrupted spirituality is a new theme. While he was still using supermarket posters, maps, and other paper ephemera to symbolize what people accept without question, his new imagery included Western landscapes, Native American objects, gears and other industrial detritus, hybrid creatures (some combination of animal, human, and machine), and repellant animals with serious jobs (vultures, dung beetles). He was still fascinated by relics and rubble.

He explained a couple of years later that he saw machines as fossils of the industrial age. “For me, the image of the gear or the defunct machine is the image of what history means, reached through the compression of time,” he said. “Scientists have discovered that if the head of a moth is cut off, it can still continue to lay eggs. Somehow I don’t think civilization is all that different.… Society is almost dead and yet it continues reproducing its madness as if there were a real future at the end of its collective gestures.”

Though he hadn’t articulated it in 1986, he had found the subject matter that would preoccupy him for the rest of his life. Broadly speaking, this was what he called “the wall of illusion surrounding society and its structures”—false history, false spirituality, government control. His shorthand for it was “the pre-invented world.” He explained that phrase in Close to the Knives:

The world of the stoplight, the no-smoking signs, the rental world, the split-rail fencing shielding hundreds of miles of barren wilderness from the human step. A place where by virtue of having been born centuries late one is denied access to earth or space, choice or movement. The bought-up world; the owned world. The world of coded sounds: the world of language, the world of lies. The packaged world; the world of speed in metallic motion. The Other World where I’ve always felt like an alien.

When David talked with Tom, he often mentioned a particular good friend, Peter. “One day,” Tom said, “it hit me. Could this be Peter Hujar?”

David told him it was funny, because just recently Hujar had said to him, “Are you talking about Tom Rauffenbart?”

Tom and Hujar had had an affair early in 1974 that lasted a couple of months. When they met, Tom knew that Hujar was a photographer. “But I didn’t know anything about his world,” said Tom. He did know that “the man had no money, ever.” He too had seen Hujar wash his jeans out in the sink and dry them on top of a radiator.

One night they went out and Hujar asked Tom if he’d be willing to close his eyes and let Hujar guide him around. “It was great fun for about two hours,” Tom said. “We’d stop places and he’d say, ‘Feel this and try to tell me where you are.’ ”

Then Tom discovered that Hujar knew certain people who were more or less famous and that he was taking pictures at Warhol’s Factory. “So I was getting the sense that this guy was sort of a mini-celebrity,” said Tom, “and that was intimidating to me. We had some really nice dates, but I just got more and more frightened, more and more self-conscious. It became hard to talk. I remember one time saying to him, ‘I’m just so impressed by who you are and I don’t feel like I’m anything,’ and Peter said, ‘Well, I’ve actually been fascinated by you.’ ”

For the only time in his life, Tom started keeping a journal—which he later found too painful to read. Hujar called him one night and invited him over for dinner. “I asked what he was making, and he said, ‘Tuna noodle casserole.” (At a certain point in Hujar’s life, that was the dish he made every night.) Tom, who was trying to learn to assert himself, said, “I hate tuna noodle casserole. No, I’m not coming.” The affair ended soon after. Not because of this spurned invitation, but because, Tom said, “I would panic inside and lose myself.”

For years afterward, this was the relationship Tom most regretted losing. And now, Hujar was David’s best friend. Tom thought, “Oh, great. Peter will tell him what an asshole I am.”

In fact, Hujar thought that Tom would be good for David, that David needed stability and Tom would give it to him. Now he’d have regular meals and maybe take better care of himself.

But Tom could sense all the fears and insecurities he’d had in his relationship with Hujar starting to build again in this new relationship with David. “I was getting moody and depressed,” Tom remembered. “I was still drinking, and I was afraid to tell David what I felt. I thought he would hate me. It was just horrible.” Tom went into therapy that spring. “I knew that if I didn’t do something about this, I was going to lose this guy.”

David’s show of “history paintings” opened at Gracie Mansion Gallery on April 27. “People were literally fighting in the gallery over these paintings,” Sur Rodney Sur recalled. “It was horrific. I’d never seen anything like it.” Major collectors had come in before the doors officially opened and before David arrived. So, he didn’t hear people arguing: “I want that one.” The difficulty, Sur said, was “when you have two people fighting over the same painting, how do you decide who gets what?”

While David missed this feeding frenzy, everything was sold by the time he showed up. He was stunned. This was exactly what he’d complained about—people buying but (he assumed) not apprehending. Gracie remembered that someone had come in a limo. “And to think that somebody would buy something who had come in a limousine—he both loved and hated it,” she said. Gracie had done her job. David was “hot,” and all the pieces went to major collections. His response to this good fortune was to announce that he would again stop painting. He told Gracie, “It’s over. I’m just going to work on my writing.”

Then he told Tommy Turner that he wanted to make a giant spider for the window of the gallery, and this creature would be preying on a man while a fan blew money out its rear end. Gracie was the spider. “Sucking me dry,” he complained to Turner.

The day after the opening, David left town with Tom. They went back to St. John’s.

David had found the relationship that would sustain him for the rest of his life, and he’d found a new direction for his work. Even so, he hadn’t quite finished with the ugly preoccupations of the previous year. He and Tommy Turner worked on their Super 8 “satanic teen” film off and on through the first half of 1986.

Jim “Foetus” Thirwell offered them a song he’d written about Ricky Kasso. He called it “Where Evil Dwells” and said they could have the music if they made that the title of the film. Turner and David agreed that it was better than the title Satan Teens. They worked out a new title shot. David stapled a piece of transparent plastic between two broom handles, and a couple of assistants held it up in front of a suburban house while David wrote the words “WHERE EVIL DWELLS.” He and Turner felt that Ricky Kasso and friends had used drugs and their own twisted take on black magic to rearrange what David called “the imposed hell of the suburbs.”

They shot footage of satanic teens around a campfire and of the Kasso figure chasing the kid he would kill. They filmed the Kasso figure gouging the eyes from what is clearly a rubber mask. So it was ham-handed. It was also a horror film of unrelenting gloom, with images of grave robbing, burning cars, and dead or dying animals.

The most original scenes are set in heaven and hell. (Kasso warned his victim that he would follow him into the afterlife.) The script describes heaven as a “bourgeois restaurant,” where Jesus, played by Rockets Redglare, sits gorging at a banquet table. A maître’d bars the satanic teen from entering.

Then there’s hell, which turns out to be as barbarous and ghastly as advertised. A number of people have been tied upside down to a locomotive engine, where they’re hit by a man in a hockey mask. Fires burn in barrels. A motorcycle with one Hell’s Angel and two female minions circles slowly. There are people in masks, people with whips, someone in a goat’s head, much smoke and chaos. The Devil (played by Joe Coleman) makes the film’s most indelible impression, whether standing on a railroad bridge and exploding the firecrackers attached to his chest or plucking a live white rat from a tray and biting its head off.

They shot the underworld scene on June 28, 1986, after wheat-pasting flyers around the East Village advertising for “inhabitants of hell: junkies, weightlifters, starving bums, suicides … human oddities, sleepwalkers … screamers, scrooges playing with money … anything you want to be or are and wish to have immortalized forever.” Such volunteers were to meet at a particular spot along Tompkins Square Park for shuttle service to hell. David had found an abandoned warehouse along the river in a not-yet-gentrified Williamsburg. Turner instructed the assembled hellhounds not to tell the locals what the film was about. “Tell them we’re filming Miami Vice,” he said. One of the actors couldn’t contain herself, however, and told some neighborhood kids that they were making a movie about Satan. The kids ran for their older brothers and fathers, who marched down to the warehouse just as filming ended. “It almost turned into a fight,” Turner said. “They threatened to push David’s car into the river.” Somehow David managed to diffuse this situation, but Turner could not remember how.

John Erdman, who played the father of the satanic teen, remembered them shooting the home scenes at an apartment on Front Street in Lower Manhattan. And then something happened between David and Turner. “Something awful, I felt,” said Erdman. “David never said what. But he pulled out. He was enraged.”

Turner did not recall this, but speculated, “Possibly the drug thing was bothering him.” Turner’s heroin addiction had intensified. When David wrote years later about making Where Evil Dwells, he did not say that he’d been angered by anything but that Turner “was being pulled around by his addiction and sometimes failed to show up for filming.”

Turner estimates they had eight hours of footage in the end, but the film was never finished. He and David created a thirty-four-minute “trailer” without sync sound to show at the 1986 Downtown Film Festival. With no sound, though, it’s not coherent. A slightly damaged Howdy Doody appears, apparently to narrate, becoming one more inexplicable image. A couple of years after this, a fire at Turner’s apartment destroyed the sound tape, whatever footage he’d stored there, his rat-fur jacket, and nearly everything else he owned. Turner escaped the blaze carrying little but his infant son, Talon.

David and Turner spoke a few times about going back to work on Where Evil Dwells, but with this film, David seems to have maxed out on dealing with both family trauma and someone else’s death wish. There were limits to what one could learn from the tragic but witless life of Ricky Kasso.

He was no longer infatuated with the worldview of Kern and Turner. He began to withdraw from Kern in particular, even though they were neighbors. Kern thought David was angry because he wasn’t using him in any more of his films. “And the fact that the drug thing just got worse and worse,” Kern admitted. David, meanwhile, had cut way down or even eliminated his own use of speed and psychedelics. The night David and Tom Rauffenbart left the Bijou together, David was on ecstasy, as he told Tom later. But Tom never knew David to take drugs. “Two sips of champagne and he would feel off,” Tom said. “Even aspirin bothered him.”

David wrote of this period in Close to the Knives:

Death was everywhere, especially in my apartment, a gentrified space right above [Kern’s] place. In my depression, I kept thinking it was [Kern]’s fragmented state of mind that was pumping death vibes up through the floor. Later I found out a woman with three kids had occupied my apartment before I got there. She apparently died a slow, vicious death from AIDS. I felt like the connection between me and this circle of friends was getting buried in veils of disintegration; drug addiction creates this vortex of psychological and physical fragmentation that is impossible to spotlight or put a finger on. [Kern] was wrestling with it and at the same time seemed unconscious of it. I thought he was becoming a creep.… [Turner] was getting more erratic and transparent in his addiction.… I felt myself at a point where I needed to either define certain boundaries for myself or get away from my life as it was.

Anna Friebe was one of the German dealers who’d been an early supporter of the East Village, and that summer she offered David a solo show. He left for Europe on July 23 and stayed until September 7. He visited Paris, but for most of that time he was in Cologne creating more “history paintings” for the Friebe Gallery.

Late Afternoon in the Forest, for example, continues the general theme of apocalypse and ruin. One of his hybrid creatures—part bird, part airplane—has crashed in the forest. Behind it sits a large alien head with its lips sewn shut. Visible in the torn fuselage of the bird-plane is a bit of gothic architecture, all arched doorways, and from it crawl a couple of red fire ants with human faces. Maybe only the hybrids survive in this future. Everything 100 percent human here seems to be an artifact, and it’s all quite small—the Greek statue of a man fighting a centaur, the Indian chief that looks like something bought from a souvenir stand, the Parthenon visible in an upper corner.

David was living and working in the gallery, since it was closed for the summer. Before Anna Friebe left town, she asked one of her other artists, Rilo Chmielorz, to look in on him occasionally. “We connected in a strong way,” Rilo said. It felt like “an eternal association.” David made a piece to give her, painting his symbols for Earth (the globe), wind (a cloud with a face, blowing), fire (a devil), and water (a snowman) on a German supermarket poster. They had intense conversations. They went to the zoo. She remembered that he was suffering from insomnia.

In History Keeps Me Awake at Night (for Rilo Chmielorz), he stenciled a sleeping man onto maps at the bottom of the piece. (He would use this sleeping figure in several subsequent paintings that suggest dream imagery.) The history he dreams of here is all violence—a criminal with a gun (the image commonly used in target practice), a headless warrior atop a headless horse, a one-eyed monster, and so on. The same monster appeared in a piece done earlier that year for the Gracie Mansion show—Queer Basher/Icarus Falling. History Keeps Me Awake is a painting about fear, from the violence he dreaded as a gay man to catastrophes that threaten us all, in his view. The titles of other pieces also convey the dystopic vision of America he’d taken as his subject in 1986: The Newspaper as National Voodoo: A Brief History of the U.S.A.; The Death of American Spirituality (begun in ’86 but completed in ’87).

Art historian Mysoon Rizk pointed out that as David developed his iconography, he began using animals to depict, among other things, “certain Sisyphean characteristics of the human condition.… Crawling bugs, in particular, appear regularly in his work, often as tenacious protagonists or super-sized heroes invoking an eternal sense of time.” Just so, David created two Dung Beetle paintings in 1986. Both feature two large scarabs rolling dung around a picture of an American eagle, and in both paintings, disaster strikes an outmoded form of human transportation—the crashed Hindenburg in one, a steam locomotive exploding off the tracks in the other. Rizk observed that in David’s work, “even human apocalypse is unable to prevent nature’s incessant struggle and cyclical compulsions.”

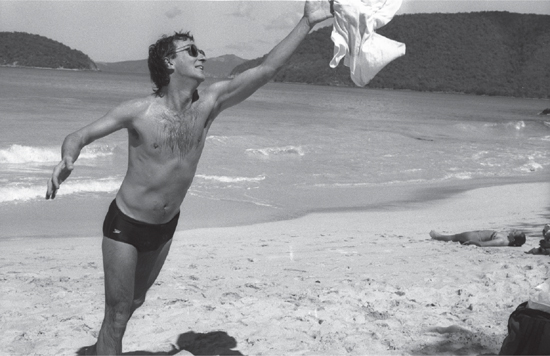

Back in New York, Tom remembered David working on Super 8 film projects during this period. Tom sometimes assisted or posed.

David was creating an image bank. He recorded Tom lifting a baby doll from a bucket and dropping flowers into water. He filmed a doll in stark black and white with a strobe going. He had Tom pose with bandaged hands, sometimes holding coins. He filmed and photographed Tom with his lips sewn shut. “It won’t hurt much,” David would joke. He attached the red string with glue and used red food coloring to simulate blood.

Tom began introducing David to the wonders of Zagat, to the city’s best steak houses, for example, since David loved steak. Another favorite spot was Union Square Cafe, the kind of great but pricey restaurant where David had never eaten before. Tom also loved cooking for David, and he introduced him to such middle-class concepts as “thread count.”

David still spent many of his nights at Tom’s. Tom gave him a drawer but they never officially moved in together. “It would have been hard without a thirty-room apartment,” Tom said. “Neither one of us was easy to live with.” They had their first fight while changing the bed. Tom liked the sheets tucked in. David asked why, and Tom said, “There is no why.”

“I hate those kinds of answers,” David steamed.

Every morning, David would announce that he’d had some dream while Tom would groan to himself, “Oh great,” but tolerate the telling. “David never slept well in all the years I knew him,” Tom said. “He’d talk in his sleep and thrash around. He was always worried that he was going to smack me. One night he did. I wasn’t upset because I knew he didn’t mean it, but he did haul off and whack me. Some nights I’d wake up, and he’d be giving some long dissertation. I’d try to talk back to see if he’d answer, but he never did.”

David editing Super 8 film at Tom’s house. (Photograph by Tom Rauffenbart)

David told Tom that he wished he never had to sleep. He would prefer to be awake all the time. “He was almost afraid to lay down and sleep,” said Tom. “It’s probably when all the demons in his mind got let loose.”

In April 1986, the Eye ran a cover story titled “The East Village Yuppie.” As the subhead put it, “Into our post-apocalyptic playground come the renovators, the upscalers, bringing tidings of America’s New Order.… Survival has replaced self-expression and upward mobility is no longer optional.”

Meanwhile, Ground Zero Gallery maintained its highly original and completely impractical operations. At the beginning of the year, scene-maker and would-be gossip columnist Baird Jones asked if he could exhibit his photos of Mark Kostabi posing with celebrities. James Romberger and Marguerite Van Cook agreed on the condition that he keep the pigs’ blood from You Killed Me First on the walls. That spring they showed Dragan Ilic, carrying out his farcical directive that they rotate all the paintings by ninety degrees every twenty minutes “to simulate a zero-gravity environment.” Then Mike Osterhout did an installation called Hell, painting the walls red, covering the floor with gravel, building a fire in the middle of the gallery, and adding a screen door. “We had all these punk kids coming in, sitting around it like it was a campfire,” Marguerite said. But the fire department came daily. From the park across the street, Ground Zero appeared to be on fire, and someone called it in every day. The firefighters had to respond, even though they knew what it was, so James and Marguerite decided to shut the piece down after a couple of weeks. Then when Marguerite did a show of her own work, she and James covered the front of the gallery with silver Mylar so it reflected the park. For an inside wall, Marguerite created a life-size photo of the Pyramid Club by placing the negative in a slide projector and getting a whole team of friends to roll developer onto a huge paper, then carry it—in pitch-dark—to a bathtub they’d filled with fixer. She put that photo up and hung her artwork on it.

The Wrecking Crew did a show at Ground Zero that summer, with the artists working from the afternoon until sometime the next day and possibly tripping, though Marguerite wasn’t sure everyone dropped acid. “David did a nice big cop eating skulls,” James remembered. “A big cop head. It was really hard to paint on the bricks, so everybody was making these ugly marks. David’s thing looked the best because he had the smooth wall.”

“We all did whatever we wanted,” Marguerite said. “With some flying Needlenoses. I mean, there were general themes of rebellion. Then the psychedelic effect of the artwork got viewers so crazy. We did some performances in there. I think we had Nick Zedd do a poetry thing, and the readings were energized by the environment. There was so much movement within the artwork it unsettled people. It exposed a wildness in the viewers that we were unprepared for.” By that fall, the gallery had moved to its last location, on East Ninth Street, and the Wrecking Crew did its final show, working outside in the backyard. David was probably out of town, since he did not participate.

In September, the East Village Eye, house organ to the scene, became simply the Eye in an attempt to broaden its appeal. It published its last issue in December, then put out a sort of greatest-hits collection of landmark pieces in January, and folded. The scene was clearly melting away, though in 1986 it was hard to see that because no one wanted to. Perhaps Wrecking Crew participant David West offered the best metaphor when he suggested that it was like the sound of a gong reverberating long after it’s been rung.

Early in October 1986, David went to West Palm Beach, one of three artists selected to paint a mural on a courtyard wall at the Norton Gallery of Art. His Some Day All This Will Be Picturesque Ruins; Four Elements would be obliterated when the show closed. But of course, he had always enjoyed painting something that he knew would be destroyed.

In the mural, symbols for all four elements hover over a Southwestern landscape, and there’s a kind of narrative at work about the destruction of Native American culture. A tornado (wind) destroys a kachina doll. The devil (fire) represents the invading white people. And so on. Earth is a globe with an emerging brain, while a snowman represents water. He’d been working this out in his mind for a few months. In another Earth, Wind, Fire, Water painting done earlier that year, he created a similar scenario, using a cloud with a face to represent wind.

He would really figure out how to combine “ruin” with the elements in the much more sophisticated Earth, Wind, Fire, and Water paintings he completed in 1987. But the mural in Florida had to be counted a success given that the Norton Gallery extended the “Walls” show for eight months. Its press release quoted David explaining his work: “It’s just recordings, so that if life were to be wiped out, these records would still exist.”

Both James Romberger and David had been invited into a summer group show in SoHo curated by Michael Carter, editor of the East Village zine Redtape. When the gallery director came to Ground Zero to pick up James’s piece, he saw one of Marguerite’s, liked it, and left with some of her work as well.

“An hour or so before the show opened, they took my painting down and put up a painting by the [gallery] owner’s wife,” said Marguerite. “Carter had an issue with this, and things took a turn for the worse. By the time we got there, they had thrown Carter up against a wall, and he was bruised and shaken up.” Carter did not recall being manhandled or hurt. But he was thrown out of his own show, along with Marguerite. He had a co-curator, however, who finally prevailed upon the owner to let them back in. Marguerite asked for her work to be returned, either that night or the next day. She was told that the back room was locked.

When Marguerite told David what had happened, he returned to the gallery with her—furious and carrying a sledgehammer. “David took his painting off the wall and told them to give me my work back,” she said. “He swung and made a hole in the wall, and then they opened up the back room quick enough. We carried my work out. David’s too.”

David then discovered that his painting Dung Beetles had been damaged. In late October, he went back to the gallery with Tom, who knew nothing about the sledgehammer incident. “David had this huge argument with the gallery owner,” said Tom. “ ‘Are you going to repair my piece?’ And the guy was saying no.” Tom realized later that David had planned this out carefully, because they’d come in on a day when the gallery was getting ready to install a new show. There stood all those pristine, freshly painted, empty white walls. David suddenly pulled out a tire iron, which he must have concealed inside his jean jacket, and announced: “That’s what you do to my painting, this is what I do to your wall.”

“He smashed about five big holes in the walls,” said Tom, who had not known that David was carrying the tire iron. Tom stood there dumbfounded as David stormed out, and the gallery owner screamed at him.

Outside Tom and David met up with Rilo Chmielorz, who was visiting from Cologne and staying at David’s apartment. “We had dinner together and we were speaking the whole time about what happened at the gallery,” Rilo said. “It was Tom who calmed down David a bit. Tom had both feet on the ground.”

When David decided to go to Mexico for the Day of the Dead, he asked Tommy Turner to come with him. He would pay for their tickets. He hoped that Turner could break his heroin addiction and thought a trip away from his drug connections and routines would help. Also, Turner had traveled in Mexico before, while David had just dipped a toe in, swinging through Tijuana and Chihuahua on the bus trip he took in 1975 while vacationing from Bookmasters.

Each of them packed a Super 8 camera, a 35mm camera, and a journal. Early on October 28, they flew to San Antonio, then caught a bus to Laredo, where they spent the night. “Over dinner, David and I discussed the different things we may feel over the next three weeks,” Turner wrote that first night in his journal, “especially concerning respective problems we will leave behind in U.S.A. necessarily.” David seemed prepared to cope with Turner’s withdrawal, and Turner seemed prepared to endure it. He’d slept through most of the trip from New York, so he sat up writing in his journal that night while David went to sleep. Suddenly David sat up, still asleep, and said, “No … life as a bird. Like over a wall. A small wall of feeling. A logging ball. The fast left right. A quiet now. A quiet month.” Then he dropped back onto the pillow. Turner could not get all the lines down because David had spoken so quickly, but he noted, “Wow. I can’t believe it. David dreams in poetry.”

The next day, they crossed the border into Nuevo Laredo, Mexico. In David’s journal entry, which is brief, he mostly recorded observations of people they encountered, and as usual, he was interested in damaged people, like a guy he calls “the elephant man.” He wrote, “Half his face was a hideous color and texture like a truck tire left in a campfire for half an hour.” David followed him, noting the reactions he elicited. He and Turner took the train from Nuevo Laredo to Mexico City. Once on board, they were shaken down by cops who checked them “for pistols.” David handed over 160 pesos, the equivalent of twenty cents.

David had started referring to Turner as “a beacon” because everywhere they went, someone would come up to him and offer him drugs. Turner would say no and David would tease, “Everybody knows.” Turner got through his first two days of withdrawal, consulting his tarot deck, trying to find a spiritual path out of addiction. “I’m going to scorch out my past on top of the Pyramid of the Sun, impregnate my future on top of the Pyramid of the Moon,” he wrote, in anticipation of their planned trip to Teotihuacán, the ancient sacred site and Aztec ruin.

Once they got to Mexico City, Turner came down with dysentery and began hallucinating. He saw a statue of a three-headed nun flying right at him, saying, “Why do you think I’m dinner?” A tortoise made of cactus tried to stab him. Some Mexican cards he’d bought now seemed to have faces on them, all staring malevolently. “I was saying all this stuff out loud,” Turner remembered, “and David was cracking up, writing it down.” Some of these images ended up in a painting David made when he returned to New York, Tommy’s Illness.

Turner recovered after a day, and they took a bus north to Guanajuato, where both shot some film at the town’s Mummy Museum. Later David printed a still from this footage, a dead child with an open mouth that he called Mexican Mummy (Munch Scream).

On November 2, they went to watch Day of the Dead rituals at a cemetery in the Coyoacán section of Mexico City. Turner reported in his journal that he no longer had any withdrawal pain. He felt great. “Flowers everywhere,” he wrote, “incense clouding crucifixes, baby angels painted with blue house paint.… Me and David felt very self-conscious filming this stuff.” This had been Frida Kalho’s neighborhood, and they found her museum, but it was closed for the holiday.

They had more chances that day to think about mortality. As they walked away from Coyoacán, they passed shattered buildings and wreckage still there from the September 1985 earthquake, which had killed some ten thousand people. They climbed aboard a bus “to film unobtrusively,” Turner wrote. “Yea right. My regular camera sounds like a bank vault being slammed when the shutter closes.” On their way to the cemetery that morning, they’d passed a seedy-looking circus, and that’s where they wanted to go next. “David was hoping very much to see a bear ride a tricycle,” reported Turner. “No such luck. The same three guys did everything. Acrobats (missed almost every attempt), clowns, musicians, lion tamers, and motorcycle daredevils.” David filmed all of this.

They found a cabdriver who agreed to take them to see Mexican masked wrestling and act as a sort of interpreter for three thousand pesos (roughly four dollars) per hour. Turner described an anarchic scene at the arena, fighting that kept spilling out into the audience, a wrestler called La Erupción with “a volcano erupting on his chest and flames shooting [up between] his eyes. Me and David were filming like locos.” Then they both nearly lost their cameras. First a security guard accosted Turner and pulled him into the lobby, demanding to see a permit. The cabdriver intervened, and it all got straightened out for a bribe of a thousand pesos. As Turner sat back down, a couple of other guards grabbed both his camera and David’s. They were told that they would have to give up their film. Again the cabbie intervened and worked it out but they had to stop filming.

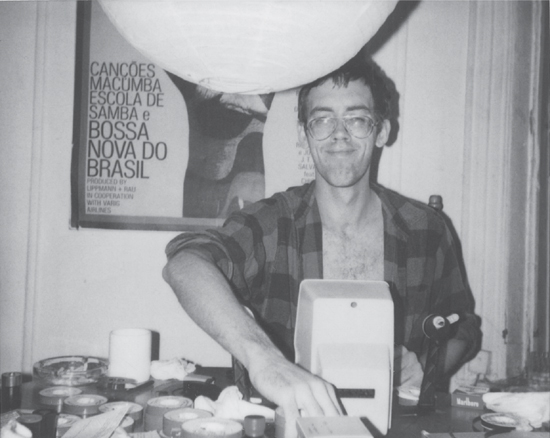

Film still [“legless beggar”] from A Fire in My Belly, 1988–89. Black-and-white photograph, 26 × 31½ inches. (Collection of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art)

David was not insensitive about using a camera here. While he wrote nothing in his journal about the Day of the Dead, the circus, the wrestling match, or the mummies, he did reflect on his own voyeurism, and the fact that it was a luxury he could now afford. “If I were penniless, I’d be just another person hustling for food there,” he wrote. “So in filming in Mexico I pushed the voyeurism to the limit, always shooting through a zoom lens whenever possible, from car or bus windows; points of elevation, third story windows, shop balconies, cliffs, etc.” He was most interested in the street characters and wrote that the best thing he saw in Mexico City was a man walking into a fancy restaurant, carrying his right shoe up to a table of wealthy diners and lifting his leg so they could see that he had no foot, “just a blood red bone covered in tissue thin skin—looked like a cow bone, the kind you see on 14th street in barrels.”

On November 3, he and Turner took a bus to Teotihuacán. David was excited because he’d heard that there were fire ants there. He had brought props with him: watchfaces, coins, a toy gun, a toy soldier, a small Day of the Dead skull, a candle, a sign, a crucifix. Once they reached Teotihuacán, they separated. Turner went to the southern end of the site to meditate and do a tarot card reading atop the Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl. David found nests of big red fire ants somewhere between the pyramids to the sun and moon. He placed the objects he’d brought with him there, took pictures, and filmed the images that would so upset the Catholic League eighteen years after his death. He filmed the pyramids and the Avenue of the Dead. At the end of the day, he and Turner climbed to the top of the Pyramid of the Moon during a thunderstorm and tried without success to film the lightning.

David didn’t talk about what the ants meant to him, just as he hadn’t talked about any of the other things he’d filmed and photographed. “He was just grabbing images,” Turner said, “and he’d use it later.” When he printed the fire ant pictures in 1988, he explained, “Ants are the only insects to keep pets, use tools, make war, and capture slaves.” In these photos, they represent human activity within pre-invented structures: time (the watchfaces), money (coins), control (the toy soldier), violence (the toy gun), language (the sign), and spirituality (the crucifix). His photos of ants crawling over an artificial eye (knowledge) and over a photo of a naked man (desire) were taken on another occasion (and the eye photo was printed at a smaller size). Writing about Untitled (Ant and Eye), he explained that humans often treat nature as an abstract concept, hardly noticing the ground they walk on. “Using animals as a form to convey information about scale or intention is to take that power away from the human and return it to the life forms that have been abstracted into the ‘other.’ ”

The next day, November 4, David flew into a rage at Turner over the loss of a receipt. It was another inexplicable blowup. Turner wanted to call his wife, Amy, because she was in the hospital. The hotel required a fifty-dollar deposit, which Turner paid. Then David told him he would hang on to Turner’s receipt, and Turner gave it to him. Turner never completed the phone call, because Amy didn’t pick up. So that evening, David said, go get your money back. Turner said, give me the receipt. The fight started there. Apparently David had lost the deposit slip but attacked Turner for entrusting it to him. “What a stupid thing to do!” And so on.

On November 5, they went to the airport together to fly to the Yucatán. They already had their plane tickets, but at the airport David announced that he’d had it with Turner and could no longer travel with him. He would go elsewhere. He handed Turner, then nearly broke, a few hundred dollars. Turner thought that “very kind.” He flew to the Yucatán, alone and astonished. He spent about a week there. “I knew David’s history of traveling with people,” said Turner. “That it could go awry. But we had always gotten along.” Turner had to take a bus back to New York from the Yucatán. He borrowed money from other tourists for the ticket.

Without Turner, David probably stayed in or near Mexico City. He sent Tom a postcard from there: “Hey Cookie, I wish in moments I could live down here with an endless supply of film—being on my own is a bit lonely but filled with strange adventure. Wish you were here and we was driving. Sometimes the slowness of busses is too much.”

David arrived home on November 18 and began to work on paintings inspired by the Mexican trip. He had promised James and Marguerite a show at Ground Zero, scheduled to open January 10.

In Close to the Knives, he wrote, “When I returned to New York City I saw [Turner] about two weeks later. He was in town a couple days and his eyes were heavily lidded from dope. I started avoiding him after that.”

Turner, however, is sure he stayed clean for several months.

Sometime in 1986—no one remembers when—Dean Savard reappeared in the East Village, living in an old Dodge van parked on Tompkins Square. According to Dean’s brother, Perry Savard, their parents bought him the van. “My parents basically said, this is the last thing we’re doing for you.”

Alan Barrows remembered that the point was to get him a van so he could leave New York and get cleaned up. And he did leave town for a while, but “he couldn’t stay away,” said Barrows. Drugs were still so easy to get in the neighborhood. Savard had with him all the paintings that artists had given him during his years at Civilian Warfare, and he began selling them out of the van to get drug money. “Eventually the van wouldn’t run anymore, and he sold the van,” Barrows said. “After that, I guess he probably lived in abandoned buildings. By that time, I couldn’t have anything to do with him. When you watch somebody go down the hole, they can pull you in with them.”

Barrows decided in December that he had to close Civilian. By then, Savard had disappeared completely. The two had been partners, but Barrows was left holding all the debt. “I had to declare personal bankruptcy,” he said. The gallery owed more than a hundred thousand dollars, most of it for advertising, but also for back rent and payments to artists.

Barrows left New York in 1987 when his partner got a job offer in Washington, D.C. “I felt like Ratso Rizzo, that character from Midnight Cowboy, spitting up blood on the bus,” he recalled. “It took me a long time to recover mentally from everything that had happened in New York.”

The day after New Year’s 1987, Tom Rauffenbart came home to find David sitting at his dining room table.

“He was very withdrawn,” Tom said. “I knew something was wrong, but he wouldn’t tell me. I tried to draw it out of him, and then he just broke down in tears. He was a wreck. I finally grabbed him. I was hugging him, and he said, ‘You can’t tell anybody. You can’t tell anybody. Peter has AIDS.’ ”