The politicians who opposed arts funding were often the same people who opposed AIDS funding.

Senator Jesse Helms and the California Republican congressman William Dannemeyer were both virulently, self-righteously homophobic. Both fought bitterly against spending a single government dollar on AIDS research, AIDS prevention, or AIDS treatment. Helms masterminded the law that banned people with HIV from entering the country. Dannemeyer backed a California ballot initiative to quarantine people with AIDS—it failed—and he once declared that PWAs emitted spores “known to cause birth defects.” In the summer of 1989, Dannemeyer outraged many when he read graphic descriptions of gay sex into the Congressional Record, an effort to alert his colleagues to “what homosexuality really is.” He was about to publish A Shadow in the Land, his book attacking the gay rights movement. In 1987, the Senate had adopted a Helms amendment (pushed through the House of Representatives by Dannemeyer) that prohibited the use of federal funds for any AIDS education materials that could “promote or encourage, directly or indirectly, homosexual activities.” Donald Francis, a pioneer in AIDS research who was later AIDS adviser to the state of California, called their efforts “truly damaging” in preventing the spread of the virus.

Dannemeyer supported all efforts to defund the NEA, after failing in his bid to rewrite its authorizing legislation so that Congress would have “oversight” of choices made by grantees. He was not leading the House effort to kill the agency, though, leaving that to a fellow Orange County, California, conservative—Representative Dana Rohrabacher. Helms, however, spearheaded the anti-NEA charge in the Senate. That September, he cooked up an amendment aimed at preventing the likes of Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe from ever getting another grant. Attached to the 1990 appropriations bill, his amendment outlawed the use of federal money to “promote, disseminate or produce obscene or indecent materials, including but not limited to depictions of sadomasochism, homoeroticism, the exploitation of children, or individuals engaged in sexual acts; or material which denigrates the objects or beliefs of the adherents of a particular religion or nonreligion.” Helms got this passed in the Senate by calling for a voice vote when only a few senators were present. But it did not pass in the House.

In late September, the Senate and House conference committee met to work out a compromise. Helms threatened his Senate colleagues with a roll call vote if they dropped his amendment, to get them on the record “as favoring taxpayer funding for pornography.” He made good on his threat that very evening, attaching his original amendment to a military spending bill, then directing all pages (who are high school juniors) and all “ladies” to leave the room. He whipped out the Mapplethorpe photos and distributed them around the Senate chamber. Other senators didn’t seem cowed. One Republican even pointed out that both Mark Twain and Chaucer would be unacceptable under the Helms amendment.

But content restrictions were on the table to stay. The conference committee simply came up with a modified version of the Helms amendment. Funds could not be used for anything the NEA thought obscene, “including but not limited to depictions of sadomasochism, homoeroticism, the sexual exploitation of children, or individuals engaged in sex acts which do not have serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.” The NEA added this language—known in the arts community as “the loyalty oath”—to its terms and conditions for grant winners. The culture war was just beginning.

“Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing” was a landmark show, among the first to focus solely on artists’ personal responses to the AIDS crisis. It had been scheduled to coincide with the first-ever Day Without Art, on December 1, 1989, a day of action and mourning over the epidemic that would be observed in arts institutions all over the country.

In her statement for the catalog, photographer Nan Goldin wrote that when she got out of rehab in 1988, she wanted to reconnect with friends she’d lost touch with during what she called “my last few years of isolation and destruction.” Goldin had been so wrapped up in her addictions that she’d paid little attention to the advancing plague. Once she was clean, though, she felt overwhelmed by how many of the people she loved or admired were now sick, grieving, or dead. When Artists Space invited her to curate a show, she saw a chance to give these friends a forum. Certainly by 1989, everyone who’d been part of the downtown scene knew someone who was dead or dying or both. This was a traumatized community.

David had Untitled (Hujar Dead) in this show, along with the three photographs of Hujar (face, hand, foot) he had silk-screened into that piece, and four prints from The Sex Series. For the catalog, he contributed a photo not in the show, a picture of some graffiti that reads, “Fight AIDS. Kill a quere [sic].”

Kiki Smith’s piece featured figures of many naked women and some babies silk-screened onto muslin, in memory of all the sisters “disappeared by AIDS,” as she put it. The plight of HIV-positive women had gotten relatively little attention at this point, and her sister Bebe had died of AIDS in 1988.

Styles ranged from that to Vittorio Scarpati’s cartoons drawn in the hospital, where he spent months after his lungs collapsed from Pneumocystis. If any type of art predominated in “Witnesses,” it was portraits, both paintings and photographs. Goldin included some Hujar portraits in the show, for example. Philip-Lorca diCorcia contributed a photo of Scarpati looking spectral in his hospital bed, like he was literally fading, while the bandages covering much of his bare chest and festive balloons hanging from an IV stand look more permanent. Married to Goldin’s old friend Cookie Mueller, Scarpati died on September 14, 1989, at the age of thirty-four.

There wasn’t much nudity in Witnesses, apart from the Kiki Smith piece, Dorit Cypis’s photo installation with nude female body parts, and Mark Morrisroe’s enlarged Polaroids of naked men. None of this was pornographic, none of it obscene. Indeed the most shocking thing in the show was a description Morrisroe wrote of his treatment in the hospital (reprinted in the catalog), about how he had “smashed the vase of flowers Pat Hearn sent me so I would have something to mutilate myself with by carving in my leg ‘evening nurses murdered me.’ “ Friends with Goldin since art school, Morrisroe had died of AIDS that summer at the age of thirty. In his last portrait, he looks sixty.

Goldin wanted an essay for the catalog from her friend Cookie, the writer, actress, and quintessential free spirit Goldin had been photographing since 1976. But Cookie also had AIDS, and by the summer of 1989, she was walking with a cane and had lost her ability to speak. (Goldin’s last photo of Cookie alive was taken at Scarpati’s funeral about two months before Witnesses opened.) The catalog reprinted a piece Cookie wrote earlier for City Lights Review. Half of it was devoted to the last letter she ever received from her best friend, Gordon Stevenson, the no-wave filmmaker (Ecstatic Stigmatic) and bass player for Teenage Jesus and the Jerks who died of AIDS in 1982. Stevenson felt that the illness was punishment for being different, for being a “high-risker.” For her part, Cookie advised, “Watch closely who is being stolen from us.… Each friend I’ve lost was an extraordinary person, not just to me, but to hundreds of people who knew their work and their fight. These were the kind of people who lifted the quality of all our lives, their war was against ignorance, the bankruptcy of beauty, and the truancy of culture.… They tried to make us see.”

When Goldin sent David a description of what would be in the show, she added a handwritten note: “I’m so happy you’ve agreed to write a piece for the catalogue.… As for how you want to approach this, it’s up to you.”

David had begun taking AZT, though it often made him vomit. He still had no opportunistic infections (like Pneumocystis). But he knew that it was time to write an essay dealing with his own mortality. As always, he would then step back to look at the context, the landscape devastated by plague—and this time, he would name some villains.

But he began by talking about a friend who’d dropped by unexpectedly, who sat at the kitchen table trying to find language for what he was going through now that his T-cell count had dropped to thirty. David wrote:

My friend across the table says, “There are no more people in their thirties. We’re all dying out. One of my four best friends just went into the hospital yesterday and he underwent a blood transfusion and is now suddenly blind in one eye. The doctors don’t know what it is …” My eyes are still scanning the table; I know a hug or a pat on the shoulder won’t answer the question mark in his voice. The AZT is kicking in with one of its little side effects: increased mental activity which in translation means I wake up these mornings with an intense claustrophobic feeling of fucking doom. It also means that one word too many can send me to the window kicking out panes of glass, or at least that’s my impulse.… The rest of my life is being unwound and seen through a frame of death. And my anger is more about this culture’s refusal to deal with mortality. My rage is really about the fact that WHEN I WAS TOLD THAT I’D CONTRACTED THIS VIRUS IT DIDN’T TAKE ME LONG TO REALIZE THAT I’D CONTRACTED A DISEASED SOCIETY AS WELL.

That passage, with its angry desperation, sets the tone. He wrote of how he resisted being comforted, of his need to witness, of his tendency to sometimes forget the disease for whole hours, of the inadequacy of memorials, of trying to “lift off the weight of the pre-invented world,” of how important it was to see his reality represented in the culture—on gallery walls, at least.

He also wrote one sentence fantasizing about the deaths of Helms and Dannemeyer: “At least in my ungoverned imagination, I can fuck somebody without a rubber, or I can, in the privacy of my own skull, douse Helms with a bucket of gasoline and set his putrid ass on fire or throw Congressman William Dannemeyer off the empire state building.” Elsewhere, referring to the attacks on Mapplethorpe, Serrano, and the NEA, David called Helms “the repulsive senator from zombieland.”

He devoted an entire paragraph to local villain Cardinal John O’Connor. The cardinal’s name came up frequently among queer activists and at ACT UP meetings. He opposed safe-sex education and preached against condom use. He had representatives on the New York City Board of Education’s AIDS advisory committee, where they lobbied to stop all sex education and AIDS education in public schools. He served on Reagan’s know-nothing Presidential Commission on the HIV Epidemic. He prohibited the gay Catholic group Dignity from holding Mass in any church in the diocese; when Dignity members protested by standing in silence during the cardinal’s homily at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, eleven were arrested, and the cardinal banned them from ever entering the cathedral again. O’Connor fought vigorously against the passage of any legislation guaranteeing civil rights to gay people. He was also strident in his opposition to reproductive freedom for women. While at work on his essay, David read an article in the paper about O’Connor’s wish to join Operation Rescue in blocking abortion clinics.

David wrote, “This fat cannibal from the house of walking swastikas up on fifth avenue should lose his church-exempt status and pay taxes retroactively for the last couple of centuries.… This creep in black skirts has kept safer-sex information off the local television stations and mass transit spaces for the last eight years of the AIDS epidemic therefore helping thousands and thousands to their unnecessary deaths.”

The comments on all three villains would soon be extracted from his 3,700-word piece and excoriated, but he had no reason at the beginning of October to anticipate trouble. Goldin loved the essay. And he had other things to do.

In autumn 1989, David had distractions at home to deal with almost daily. He lived above what had once been one of the great Yiddish theaters, a space the landlord began converting that year into a multiplex. In June, the theater roof collapsed, but most of the irritations suffered by tenants were less spectacular: no lights in the hallway, phone cables cut, interruptions to electrical service, severe leaks, drilling and loud tapping during daylight hours.

The tenants had been keeping a “harassment list” all year, but problems began to intensify in August. For nine days in September, roof demolition created “noise so loud that a normal conversation cannot be heard,” the list reported. David got his lawyer involved to try to stop the removal and replacement of the roof. On October 2, the list noted: “Water pouring down D. Wojnarowicz’s west wall, down wall in common hall area, and pouring down the stairs.” The complaints cited most often were high-decibel noise and leakage.

David wanted to devote the remainder of the year to ITSOFOMO and to his upcoming retrospective at Illinois State University. He had a new piece in mind and ideas about the catalog. Barry Blinderman, director of University Galleries, suggested to David that they call the show “Tongues of Flame.” He had secured a fifteen-thousand-dollar NEA grant toward the exhibition and catalog.

On October 7, David flew to Bloomington-Normal, the twin cities of central Illinois. He and Blinderman worked on an interview for the catalog, some of it conducted in the car while they drove around town, discussing, for example, the idea Blinderman would eventually use as the interview’s title, “The Compression of Time.” David said, “You look down there and you see a white car moving by, and now it’s gone; the fraction of time that the action inhabited is so brief that all we can do is carry the traces of memory of it. That’s what life is. Every minute, we pick up the traces of what just happened; perception and thought and memory are continuous, and yet somehow we make these delineations or these borders between what’s acceptable and what’s not. Time is not something that’s set to a strobic beat. For instance, if you’re in a place where violence is occurring—possibly occurring to yourself—time takes on a totally different quality than it would be if you were in an introspective quiet place. Time expands and contracts constantly, and yet we set it to a meter which is completely unreal.” Since David was staying with him and his family, Blinderman also saw how sick David was, constantly nauseated from AZT. He was in Illinois for a week.

Back in New York, David asked Jean Foos to design his catalog. She’d just become art director at Artforum, but they’d been acquainted since the early East Village days. She’d painted at the pier, she’d introduced him to Keith Davis, and her boyfriend was Dirk Rowntree, one of the few people David was still in touch with from the seventies. David explained that he would be giving her a painting in lieu of payment.

He knew what he wanted for the cover—either a photo by George Platt Lynes or an image that would approximate it. Lynes is best known for his erotic male nudes, photographed when such pictures were completely taboo. (He died in 1955). The picture David loved, though, was not a nude but an image of a man’s head in profile. The man appears to be screaming. John Erdman and Gary Schneider owned this photo, and David wanted to buy it from them. “He often asked to see it when he came over,” said Erdman, who refused to part with the picture. “I don’t know if he was going to use this for the cover of the catalog or if he was just going to study it. But whatever coolness happened between us was because of this. He was angry that I wouldn’t give it to him.”

David then photographed a number of people standing in strong red and blue light—just their heads with mouths open, as if screaming. The dancers who would be part of ITSOFOMO were all photographed that way, as was Steve Brown. David decided to use the picture of Brown, screaming, on the cover of his catalog. Back in 1985 when David was in the Whitney Biennial, Brown teased him about Robert Hughes’s panning of the show in Time. (Hughes called David’s work “repulsive” and declared that edition of the Biennial to be “the worst in living memory.”) In an interview with Sylvère Lotringer, Brown recalled telling David that he couldn’t wait for the day when Time had David’s face on the cover with the caption “Misfit or Messiah.” David thought Brown was making fun of him, and said he was putting his face on the catalog to get back at him.

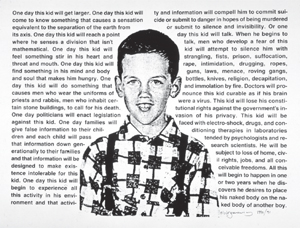

David also began work with Foos on a new piece that would appear in the catalog but not hang on the wall in Normal, a school photo of himself as a boy, surrounded by type. “One day this kid will get larger,” the text begins. “One day this kid will feel something stir in his heart and throat and mouth.… One day politicians will enact legislation against this kid. One day families will give false information to their children and each child will pass that information down generationally to their families and that information will be designed to make existence intolerable for this kid.”

This would become one of David’s best-known, most widely distributed works, translated into German—he hoped to get it into other languages as well—and also presented with a little girl at the center. Critic Maurice Berger remembered encountering it in a show in 1990. “The juxtaposition of freckle-faced, jug-eared innocence with the poisonous reality of homophobia moved me deeply,” Berger wrote. “And while I have been ‘out’ for almost a decade, the work helped me to accept a part of my queer self that I had never before owned: the gay-bashed, self-hating kid who struggled to survive.”

Untitled [One day this kid …], 1990. Gelatin-silver print, 30 ×40 inches. (Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York)

David’s essay “Postcards from America: X-Rays from Hell” had been typeset while he was in Illinois. On October 17, Susan Wyatt, executive director at Artists Space, looked at the galleys for the “Witnesses” catalog and read his piece for the first time. She was alarmed. Artists Space had received an NEA grant of ten thousand dollars toward the exhibition and catalog. (The total budget for “Witnesses” stood at thirty thousand dollars.) Wyatt now anticipated difficulties because of the new Helms amendment. She also worried that the essay could be libelous. Artists Space had never even published a catalog piece that used four-letter words. Wyatt felt that she had to protect the organization, but she also wanted to protect the NEA. As she put it later in her written account of this incident: “It’s an incredible responsibility when you realize the whole future of the public funding of art has come to rest on your shoulders.” That’s what she felt was at stake.

She sent the “Postcards” essay to a lawyer on the Artists Space board. Then she called David Bancroft, the NEA program specialist responsible for the grant, and asked if they could change their award letter to state that NEA money would fund the exhibition only—not the catalog. She already had a five-thousand-dollar grant from the Mapplethorpe Foundation and could allocate that money to the catalog. Bancroft didn’t think there’d be a problem with that, but said he would call her back.

Meanwhile, the lawyer on her board advised her to get David to take out the names of Helms, Dannemeyer, and O’Connor. He could just say “government officials.” But Wyatt realized after a “difficult” first phone call with David that there was no way in hell he would do that.

According to Nan Goldin, Wyatt also called her. “She asked me to censor,” said Goldin. “I talked to David. He said he refused to censor. She read me the lines she wanted censored. ‘The fat fucking cannibal in black skirts.’ The only thing he agreed to do was to take ‘fucking’ out. And I quickly became aligned with him. First, she talked to me and tried to get me aligned with her. And I didn’t initially understand why it was so important to David to keep those lines in. But then of course I supported him a hundred percent.”

Wyatt did not recall asking Goldin to contact David, but said, “I tried to keep Nan in the loop. She did get to be very difficult. She got very angry at me.” Goldin was still based in Watertown, Massachusetts, near the hospital where she’d recovered, and was commuting to New York. But Connie Butler, who’d just taken a curator job at Artists Space, remembered her as “a really forceful presence. She was very emotional and trying to be protective of the artists and of David.”

When David later typed up notes for himself labeled “NEA—Artists Space Flap,” he recounted his first couple of conversations with Wyatt this way: “Susan Wyatt calls to ask that I change certain things I refuse she asks disclaimers I refuse she says [Artists Space] will do disclaimers—she tells me her lawyer asks me to sign liability waver in case of lawsuits—I say send it to me.”

David went to the Center for Constitutional Rights, where he was advised that the cardinal could sue over the assertion that he’d suppressed safe-sex information. But if the cardinal did that, the CCR would defend David pro bono. He then signed Artists Space’s liability waiver, assuming financial responsibility for all “losses, liabilities, damages, and settlements” resulting from his essay.

Wyatt spent the next few days trying to determine whether the NEA would even want credit for funding “Witnesses.” Goldin had commissioned new work from some of the artists, but nothing had come in yet, so Wyatt wasn’t sure what would be in the show. She speculated that some of it could be sexually explicit. When she couldn’t get an answer from NEA staff, she decided to go ahead with crediting the agency—usually standard practice—on the outgoing press releases.

On October 24, NEA program specialist David Bancroft called Wyatt to confirm that she could change the award letter, deleting the catalog from what would be funded. He advised her to simply revise her budget and to formalize the change in writing. (He later called this “Susan’s interpretation of our conversation.”)

On October 25, Wyatt was in Washington to meet the new NEA chairman, John Frohnmayer, with a delegation from the National Association of Artists’ Organizations. Frohnmayer had held the job for three weeks. Now, briefed on Wyatt’s queries, he asked to have a word with her in private. Later, when he too wrote an account of all this, he said he did not know at that point that she wanted to excise the catalog funding from the grant, while Wyatt maintains that she told him that day. (Her letter formalizing that change did not arrive at the Endowment until November 7.) Frohnmayer then asked her to remove NEA credit from the catalog and to print a disclaimer. She decided that was only fair. She’d already included a disclaimer on behalf of Artists Space, stating that the organization and its board “may not necessarily agree with all the statements made here.”

At this point, no one at the NEA had seen the art to be exhibited. So, on October 30, Frohnmayer sent Drew Oliver, director of the NEA’s museum program, to New York to look at slides of the work selected by Goldin and to obtain a copy of the catalog text. Artists Space still didn’t have all the work. Before Oliver arrived, Wyatt had gone through the material they did have with the lawyer on her board, who said that the only image that might be problematic was a Hujar photo of a naked baby and advised that they track down the parents. Then Oliver arrived to have a look. Wyatt described him as “pleasant” and “unsurprised by everything.” However, that wasn’t what Frohnmayer conveyed in his book about running the agency, Leaving Town Alive. Oliver “reported back that the images were clearly explicit (that is, they whacked you between the eyes so you wouldn’t miss the point), reflected anger toward society about AIDS, and had some nudity,” wrote Frohnmayer. “Drew thought that a disclaimer was necessary, because the material was cruder and potentially more problematic than Mapplethorpe’s photos.”

Frohnmayer called Wyatt just hours after Oliver left Artists Space to request that the Endowment’s name be disassociated not just from the catalog but also from the whole of “Witnesses.” He wanted both the removal of the credit line from all signage and future press releases and a disclaimer stating, “The opinions, findings and recommendations included herein do not reflect the view of the National Endowment for the Arts.” Wyatt thought that was like saying, we don’t approve of this show, which we had nothing to do with. It didn’t make sense to her, so she refused. But she tried to work out some new disclaimer language that Frohnmayer would accept.

On November 2, she called him with her counterproposal, and Frohnmayer asked her to voluntarily relinquish the grant. She said she would have to consult her board. Frohnmayer then decided that “not acting, particularly when Susan Wyatt had dumped this steaming, writhing mess on my desk, would be a declaration of weakness.” So the next day, when Wyatt was again in Washington for a meeting, he had the NEA legal counsel hand her a letter declaring that “certain texts, photographs and other representations in the exhibition may offend the language of the FY 1990 Appropriation Act”—in other words, the Helms amendment. Frohnmayer acknowledged that the grant for “Witnesses” was made in fiscal year 1989 and therefore not subject to the amendment, but, he wrote, “Given our recent review, and the current political climate, I believe that the use of Endowment funds to exhibit or publish this work is in violation of the spirit of the Congressional directive.… On this basis, I believe that the Endowment’s funds may not be used to exhibit or publish this material. Therefore Artists Space should relinquish the Endowment’s grant for the exhibition.” In addition, he asked Artists Space to “employ the following disclaimer in appropriate ways,” for example, on all its press material: “The National Endowment for the Arts has not supported this exhibition or its catalog.” The Artists Space board met on November 7 to vote unanimously not to relinquish the grant. Not voluntarily, at least. They hadn’t yet received a penny of it.

David, meanwhile, knew nothing of these machinations. He’d signed the waiver accepting financial responsibility for any “damages” caused by his essay, and he thought that was the end of it.

On Monday, November 6, the Los Angeles Times broke the story that the NEA wanted its grant money back. The exhibition was “said to include homoerotic sexually explicit pictures and text materials that criticize a variety of public officials.” David was not named, nor was he aware of this story appearing in Los Angeles.

So he was blindsided on Tuesday when he got a call from the New York Daily News. Was he aware, a reporter asked, that the NEA was about to rescind a grant for the “Witnesses” show because of his essay? The ostensible reason, said the reporter, was that “it’s too political.” The reporter asked, what’s in your essay? David spoke to him at length but would not give him the inflammatory “cannibal” sound bite. Later that night, Susan Wyatt called him. “She tells me not to speak to press—keep focus on show,” he wrote in his summary of events. “I relate reporters remarks mention LA Times story she says story is untrue none of it has anything to do with my writing—it’s the show itself maybe erotic stuff.” Wyatt points out that if she said this, it was because she assumed that the NEA had accepted her proposal to separate the catalog from the grant. Therefore the catalog could not be the problem.

That same night, the city elected a new mayor, David Dinkins, first African American to hold that office. The next morning, November 8, David went out to buy a Daily News, thinking that certainly that story would overwhelm a little item about an art exhibit. He was shocked to see that the Daily News had done a wraparound supplement on the election and beneath that was the regular front page, blaring “CLASH OVER AIDS EXHIBIT.” The story quoted Susan Wyatt saying that she’d alerted the NEA, concerned that Jesse Helms “might not particularly like the artwork.” Then the piece described David’s “photo essay,” conflating The Sex Series with the “Postcards” essay. “His photos include heterosexual and homosexual acts with accompanying text that describes O’Connor as a ‘fat cannibal in a black skirt’ and rips the Catholic Church’s stance forbidding teaching about safe sex practices,” the story said. (The misquote of the “cannibal” line indicates that this reporter did not have the essay but probably had a source inside the NEA.) The only quote from David was “I understand the gallery’s fear. But if the grants have already been given out, is the law now also retroactive?”

That day, Frohnmayer issued a statement announcing that he would withhold payment of the grant to Artists Space: “What had been presented to the Endowment by the Artists Space application was an artistic exhibition. We find, however, in reviewing the material now to be exhibited, that a large portion of the content is political rather than artistic in nature.” This statement did not mention David or any other artist by name. Nor did it mention the catalog. But when a reporter from the New York Times called him, Frohnmayer declared, “There are specific derogatory references in the show to Senator Helms, Congressman Dannemeyer and Cardinal O’Connor which makes it political.” When Wyatt spoke to the reporter, she clarified that these references were not in the show, just in the catalog—“strong statements written by the photographer David Wojnarowicz.”

When that story ran on November 9, the show hadn’t even been installed, and the catalog, if printed, was not yet available. David would not tell the reporters calling him what was in the essay. He had started recording his phone calls with them and others apropos the controversy. Phil Zwickler also came by that day and filmed him as he talked on the phone. His emotions ranged from rage to consternation to sorrow. Occasionally Zwickler panned over to the television, where the Berlin Wall was coming down.

Cardinal O’Connor released a statement that day: “Had I been consulted, I would have urged very strongly that the National Endowment not withdraw its sponsorship on the basis of criticism against me personally. I do not consider myself exempt from or above criticism by anyone.”

Wyatt called David with the news. She’d been telling the press that she was sure David would be happy about the cardinal’s gesture.

“I find his benevolence questionable,” he told her. “If he would completely reverse the church’s suppression of safer-sex information and back off from abortion clinics, I would extend my appreciation to this man. But I think it’s a political tactic, and I won’t be fooled for a second.”

Wyatt told him that Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a Democrat from New York, would get up on the floor of the Senate to support Artists Space but had to see David’s text first.

David replied, “You think he’s going to get up in support of—”

“Yes I do,” Wyatt said.

“Those quotes?”

“I do.”

“About Jesse Helms?”

“I absolutely, honestly do.”

“It’s hard for me to fathom,” David told her. “They couldn’t get behind a bunch of photographs. Why would they get behind something that is more direct?”

Wyatt called him back later that evening to thank him for challenging her. “It helped me,” she said. “It made me think about why a politician has to read a text before he can support freedom of speech.”

Cookie Mueller died of AIDS on November 10, 1989, at the age of forty.

On Sunday, November 12, the New York Post, a right-leaning tabloid owned by Rupert Murdoch, ran an editorial titled “Offensive Art Exhibit”—about the show no one had yet seen. In high dudgeon, the Post declared that funding anything that criticized Cardinal O’Connor was like funding work that glorified Hitler. David clipped this and wrote along the edge: “Just one of many articles and editorials distorting issues.” Later he used the editorial in a lithograph, printing a voodoo doll on top of it.

On Monday, Frohnmayer told the press that he regretted using the word “political” when describing the problem with the Artists Space grant. His reason, more precisely, was that between the application for the grant and the installation of the show (not yet seen), there’d been “an erosion of the artistic focus.”

The next day, conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein informed the White House that, because the NEA had canceled the grant to the “Witnesses” show, he would decline the National Medal of Arts, which he was scheduled to receive that Friday,

Meanwhile, David was getting increasingly frustrated with Artists Space. “Tired of restraint of Susan while bigots speak unrestrained,” he wrote in his notes. He thought they should fight the NEA. Legally, they had a case. Wyatt said Artists Space did consider a lawsuit, though she did not mention this to David. The lawyer advising her warned that it could take years and drain the organization’s resources. Also, the NEA was an important funder for them.

David hadn’t gone into much detail in his essay about what the “fat cannibal” had actually done. He decided he better get the facts out. David went to see Ann Northrop at the Hetrick-Martin Institute, an agency serving LGBT youth. Northrop worked there as an AIDS educator for teenagers in the metropolitan area. She was also very active in ACT UP, which was then planning its Stop the Church action aimed at Cardinal O’Connor and Catholic conservatism. David wanted to talk to Northrup about the campaign against the church, and they had a long conversation. David also consulted with ACT UP compatriots Jim Eigo and Richard Elovich. He then created “The Seven Deadly Sins Fact Sheet” with specific information on the villains—not just O’Connor, Helms, and Dannemeyer but also Mayor Ed Koch and others. He followed that with “Additional Statistics and Facts,” much of it about the Catholic Church. As someone who had been a sexually active teen, David was especially incensed about the archdiocese’s lobbying against teaching about safe sex in public high schools. As someone who had been a hustler, David was outraged that at Covenant House, the church’s safe haven for teenage runaways, residents could not get safe-sex information or condoms.

On Wednesday, November 15, Frohnmayer came to Artists Space to meet with thirty-five members of the arts community, including Nan Goldin and David. He was one of several to read a statement to Frohnmayer. It said, in part:

What is going on here is not just an issue that concerns the “art world”; it is not just about a bunch of words or images in the “art world” context—it is about the legalized and systematic murder of homosexuals and their legislated silence; it is about the legislated invisibility and silencing of people with AIDS and a denial of the information necessary for those and other people to make informed decisions concerning safety within their sexual activities.… I will not personally allow you to step back from your original reason for rescinding the grant, which was that my essay and the show had a political rather than artistic tone. You are now attempting to jump from one position to another … hoping to come up with one that sticks. It is obvious that you are in bed with Helms and Dannemeyer, and that your ignorance or agenda, both of which I find appalling, are clearly revealed by your actions.

Frohnmayer was told by others: “You have politicized the NEA.” “You are a coward.” “You have sold out the artists of this country; you should resign.” Near the end of the meeting, David confronted him again, asking, “What do you think of men who love men and women who love women? What do you think of men who have sex with men and women who have sex with women?”

Frohnmayer told him, “I refuse to answer that; that is private.” The new chair of the NEA was a former chair of the Oregon Arts Commission and a Portland lawyer. Though appointed by President George H. W. Bush, he was no right-winger. He was more like the new recruit sent to the front, taking a few bullets and endangering those around him. Under Frohnmayer, the NEA began trying to anticipate and parry critiques from the far right—and learned the hard way that there was no appeasing them.

Few on the “art” side of the culture war saw what was beginning here, while the far right found a uniquely exploitable world: skilled professionals making highly charged imagery they could take out of context. The right-wing frothers soon learned that, yes, nuance could be crushed, intimidation would work, and facts did not matter. Right-wing media would get the lies out unchallenged. (Early fomenters of crisis were the Washington Times and the New York City Tribune, both owned by the Reverend Sun Myung Moon’s Unification Church.) Meanwhile, the Frohnmayers and Wyatts of the art world thought they could reason with the right, thought truth would change perceptions. They thought this was an episode, not the beginning of a train wreck. But David, with his rebelliousness and his passion and his hair-trigger temperament and his illness, which had made him even more sensitive to the total blockage in society—he got it immediately.

That day at Artists Space, Frohnmayer got his first look at the show, scheduled to open the next day. “It was a bleak and disturbing exhibition,” he wrote. “One could find some penises and some scatological language, but the intent was far from prurient. It wasn’t as crude as Drew Oliver had described, but more oppressive and hopeless and depressing.”

That night David went to Cookie’s funeral at St. Mark’s Church, an event that went on for hours because so many people wanted to speak about her.

The next day, November 16, Frohnmayer restored the grant, specifying that the money could not be used for the catalog. Some fifteen hundred people mobbed Artists Space that evening for the opening of “Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing,” while Art Positive, a collective organized to fight homophobia and censorship in the arts, demonstrated against the Helms amendment out on the street.

David did not attend.

Allan Frame, who had photographs in the show, said, “The whole fanfare was about him so I thought, ‘Wow—he’s not even there.’ I went home that night and called him. I’m glad I did. He was just alone at home. Nobody had called.” Frame had had little contact with David since directing Sounds in the Distance.

But David had considered attending. Phil Zwickler came back to document the day, and David told him he’d been up all night finishing a personal statement about the controversy and “The Seven Deadly Sins Fact Sheet” to slip into the catalogs. He could drop that off before the opening, but realized there might be cameras around that night. He didn’t want his face out there. As he told Zwickler, “If a nutcase like Dannemeyer can occupy a position in governing this country, imagine what’s walking around the streets.”

Besides, he had another statement to finish, this one to the Artists Space board, detailing his distress over its agreement to separate the catalog from the show for funding purposes, thus severing his words from contact with taxpayer dollars. He didn’t know that Wyatt had suggested this herself back in October. He thought that Artists Space had given Frohnmayer a way out by agreeing to it. If the board had said no, David wrote in his statement, “[Frohnmayer] would have had no choice but to agree to fund the entire show with catalogue included thus sending a message across the board that we still retain our civil rights and our constitutional rights even in the face of possible loss of funding.” He delivered it to Artists Space the next day.

On November 22, conservative columnist Ray Kerrison compared David and his supposed religious bigotry to Louis Farrakhan (leader of the Nation of Islam and a notorious anti-Semite) in the New York Post. The same day, in his syndicated column in the Post, Patrick Buchanan attacked David, the NEA, Frohnmayer, and “Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing,” which he described as “a New York exhibit of decadent art, i.e. photos of dying and sometimes naked homosexuals.” Buchanan also invoked Farrakhan, who’d been condemned by liberals for calling Judaism “a gutter religion.” Now none of those liberals would stand up to David and “the militant homosexuals’ rhetoric of hatred against Roman Catholicism.”

David worried about the impact this firestorm would have on his retrospective in Normal. That day, he composed a three-page single-spaced letter to the dean of Illinois State University’s College of Fine Arts, explaining why it was important to him that “Postcards from America: X-Rays from Hell” be included in the “Tongues of Flame” catalog.

“Have you ever woken up one morning and read in the daily paper that you have lost your constitutional rights against the government’s invasion of your privacy?” he wrote. “I did—within the last four years the Supreme Court made such a decision in regards to homosexuals.” He laid out facts and statistics about AIDS, about the Catholic Church’s stance, which he regarded as “murderous,” and about the actions of Helms and Dannemeyer, which had also cost people their lives. He did not consider his outrage over these issues to be radical. He knew that the dean and Illinois State University might now be under pressure because of the NEA funding for “Tongues of Flame.” “I sympathize with what that pressure feels like, in which our individual characters are called into question in a political climate that seems to care little about the basic issues of truth contained in what I might have to say.… I would appreciate your help in supporting my right of free speech under the First Amendment.”

On November 23, David went to New Orleans with Tom. He returned on November 29, in time to participate in a reading at Artists Space with Eileen Myles, Richard Hell, and several others. David wore a Reagan mask and placed his text inside a copy of Horton Hears a Who.

On the first Day Without Art, December 1, he read unmasked at the Museum of Modern Art. Also on the program was Leonard Bernstein, playing three pieces he’d composed in memory of friends who’d died of AIDS. Lavender Light Gospel Choir performed. Actress Jane Lawrence Smith (Kiki’s mother) read a piece selected by Philip Yenawine, who was the museum’s director of education and also part of Visual AIDS, the organization behind this observance. But Yenawine thought David’s reading was the most powerful moment. Yenawine had asked him to read from his targeted essay, a section related to its real subject: mortality.

“I worry that friends will slowly become professional pallbearers,” David read,

waiting for each death, of their lovers, friends and neighbors, and polishing their funeral speeches; perfecting their rituals of death rather than a relatively simple ritual of life such as screaming in the streets.… I imagine what it would be like if friends had a demonstration each time a lover or friend or a stranger died of AIDS. I imagine what it would be like if, each time a lover, friend or stranger died of this disease, their friends, lovers or neighbors would take the dead body and drive with it in a car a hundred miles an hour to Washington D.C. and blast through the gates of the white house and come to a screeching halt before the entrance and dump their lifeless form on the front steps. It would be comforting to see those friends, neighbors, lovers and strangers mark time and place and history in such a public way.