David remained isolated through the summer of 1991 and into the fall. In late July, he wrote a letter to Judy Glantzman, who was again upstate for the summer. “I was so ill since you left,” he told her. “It got pretty extreme where I went so dark that I couldn’t call people or speak to anyone other than Tom in order to get help from him.” Then he started taking steroids, which magically cured his intestinal problems. He felt better than he had all year. Now he could finish Memories That Smell like Gasoline. He attached a letter he’d written her a few weeks earlier at the height of his misery. He hadn’t mailed it then because it was so bleak and ugly. He was not willing to go through that again. He’d found a book outlining how to commit suicide. He wanted the option.

At some point, I had heard that David was feeling poorly—and that he wanted no contact with anyone. We were only acquaintances, but I’d felt some connection with him ever since meeting him through Keith Davis, and his work moved me. I decided to call him. I left a message offering to get groceries or do laundry. He would not have to talk to me. I could hand a bag in at the door. He didn’t take me up on that.

But he called me on July 29 after he’d started the steroids to tell me that his life had been hellish since the end of the trip west. He’d had constant nausea and constipation and couldn’t get out of bed. Now he was supposed to leave the next day for the long-delayed drug trial in Boston, but he’d canceled. It would have meant more biopsies, self-administered injections, and blood drawn every day. Then if he felt bad and didn’t show up for a procedure, they’d kick him out. “I totally stopped talking to people,” he said. “I wouldn’t even tell the doctor what my symptoms were. I’m losing touch with everything. Art—it’s all meaningless. It’s an issue for me, whether I’ll ever work again.”

He complained that his doctor was treating him “like an emotional basket case” and would not discuss suicide with him. “He freaked,” David griped. “His reaction was ‘don’t worry, I won’t let you suffer.’ ”

“He was a very difficult patient,” Dr. Friedman said. “A million questions. But he was difficult because he was in an impossible situation. The options were so limited. How could he not be angry? How could he not be volatile? How could he not be frustrated?”

David seemed to have as much trouble communicating with his doctor as he did with Tom. He told me that before he started the steroids, he’d been injecting himself with interferon, and “no one knows why.” I’m sure the doctor knew why. David just had a hard time hearing what the doctor was telling him. He’d get lost. Or he couldn’t take it in. “He’d get overwhelmed and just give up,” said Tom, who urged him constantly, “you have to tell the doctor if you don’t understand what he’s saying.” Tom sometimes sat down with David, wrote out his questions for the doctor, then went with him to the appointment.

On August 1, David noted in his journal that the nausea, constipation, and fevers were back. He went through his address book. Most of the people he wanted to speak to were dead.

Sometime in August, a fired destroyed much of Tom’s apartment. A neighbor phoned him at work to tell him, and Tom called David to ask him to go look. David rang him back to say, “It’s bad.”

Tom had left a lamp on. Firemen speculated that one of the cats knocked it over into an old chair, where it smoldered into a small flame. In any case, the place was a mess, mostly from smoke and water damage. Most of the furniture was not salvageable. Part of Tom’s large cookbook collection was ruined. A supermarket poster David had given him had water damage. A small painting of a tornado that David had made for him was completely black.

“I didn’t know what to do, so I said to David, ‘I guess I’ll be staying at your house for a bit,” Tom recalled. David could not understand why Tom wasn’t more upset.

“I was sort of calm. I went and had dinner with him. I was laughing,” Tom said. “Actually I was shell-shocked. I didn’t quite know what to do, but being upset wasn’t going to make it any better. I don’t freak out. He would explode and scream and throw things. That’s not my way—and he was really upset about that. I said, ‘Well, David, we’re just different.’ ”

That weekend, about twenty of Tom’s colleagues came to the apartment to help carry out the wreckage. David was there too but decided he couldn’t handle being around so many people. He went home. Meanwhile, Tom’s cat Evelyn disappeared. Someone in the crew hauling things out had left the door open, so Tom worried that she had gotten out of the building. He began hunting for her.

In the midst of the chaos, David called. Marion had put together a sheet of his old photobooth pictures and he’d left them at Tom’s house. Where were they? Tom didn’t know.

David said, “Those are very important to me. I have to have them.” Marion had a copy but he did not want to ask her for it.

“I told him, ‘I’ve got twenty people here helping me, the cat’s gone, I can’t find her, and as we go through things, I’ll see if I have it.’ But David wanted me to look right then. I said, ‘No, I can’t do it.’ And he got furious,” said Tom. “Then the next thing I know, he’s outside walking up and down the street, looking for Evelyn.”

Eventually, the photobooth pictures turned up. The cat was found in the empty apartment across the hall, hiding behind the stove.

Nan Goldin had come by to photograph David. He posed next to the baby elephant skeleton in what looks like Hujar’s suit jacket, with his hair slicked back. And he’s wearing makeup. Nothing heavy—just foundation. When I asked Goldin about the makeup, she explained, “He wanted to wear a mask.”

Goldin inadvertently played a role in one last flare-up between David and Marion Scemama. They still spoke on the phone occasionally. One day that fall, Marion called him to say she’d run into Goldin in Paris, and Goldin told her all these things David was saying about her. Things like “she’s fucked up, she’s crazy.”

“I said to him, ‘You swore to me that you wouldn’t reject me again, and here you are saying to everybody that I’m fucked up and people believe it,’ “ said Marion. “We spoke for an hour or two. We start getting mad at each other and then we cooled down and he explained certain things to me—that he went through depression after the trip, that he couldn’t deal with certain things about me, et cetera. When we hung up, we were not saying, OK it’s over. We just cooled down. But that was the last time we ever spoke to each other.”

Goldin wrote David an apologetic letter, saying that Marion had misinterpreted what she’d said.

Occasionally David went to visit Anita Vitale, who was still running the city’s AIDS Case Management Unit. He would sit in her office and they’d chat, sometimes about Tom as he and David went through their ups and downs.

One day in the autumn of 1991, David told her that he’d been diagnosed with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI), a form of tuberculosis usually found in birds. People with healthy immune systems are not susceptible. For those with fewer than fifty T-cells, however, this was not an unusual opportunistic infection—and it was David’s first such infection. Years later, Anita could still remember his despondent tone of voice. “Pigeon shit in my lungs,” he called it. Tom did not recall hearing about the MAI before David entered the hospital. Instead, David told him that he felt like he was trying to breathe underwater, that something was weighing him down. But Tom saw that David was terrified.

David knew what it meant when the bird and animal diseases set in: time to put one’s house in order.

Sometime in October, David called his half-brother, Pete Wojnarowicz. They had not spoken in more than ten years. Not since David was a busboy at the Peppermint Lounge.

Pete was thrilled.

David had simply fallen out of his life, and he never knew why. He figured that maybe during their last conversation—the night David called him from the Pep—he’d said something wrong. He’d get the occasional update from Pat or Steven. He knew about David’s appearance in Life magazine in 1985. He knew David had AIDS. Pete would say, “Tell him to call me.” He’d gotten David’s number from Steven and left messages but David had never called back. Until this time. The end time.

Pete worked as a UPS driver. He was married and lived in New Jersey. The Saturday after David called, Pete drove into Manhattan to meet him at the loft. “I got up there and hugged him,” Pete remembered, “and I said, ‘Why the fuck didn’t you call me in all these years?’ He just said he was sorry.”

They spent the day together talking. About their father, for one thing. David had believed since childhood that Pete and his younger sister, Linda, were the favorites, that their father had only beaten him and Steven and Pat.

Pete told him, “No. Sorry. There were no favorites in that family.” He sensed a kind of relief in David, who said, “I’m sorry you had to go through that.”

David told him about Hujar—how Hujar had saved his life and made him believe in his work.

Pete admired what passed for decor in David’s loft, especially the baboon skeleton. He asked how the hell David ever got that into the country.

David said, “You want it?”

Pete declined. Then when he came back two weeks later, the baboon was gone. David had given it away, and Pete was filled with regret. If he’d known that David wanted to get rid of it, he would have taken it. “Because I didn’t really want nothing from him,” Pete said. “I was there to get to know my brother, and that was it.”

David had been meeting periodically with James Romberger, and sometimes with Marguerite Van Cook as well, to work on the comic book version of David’s life story, Seven Miles a Second. They’d started in 1987 after Romberger and Van Cook closed Ground Zero Gallery and had completed part one—David’s childhood hustling stories—within a year. Romberger spent a long time drawing the second part, working from a sheaf of David’s writing about his teenage years on the street, especially the adventures with Willy. That was completed, with Marguerite’s coloring, sometime in 1991.

They had settled on the cover. At David’s request, Romberger drew him running down Park Avenue, with one foot anchored in the ground, like a tree root, and the world breaking off in front of him. Romberger also drew two circular insets with David-style imagery—a head in flames and a skeleton with brain and eyeballs intact. They had an ambitious plan for lenticular animation on the cover. (This is usually a simple effect, like a winking eye.) The images would shift as the reader moved the book. The kid would be trying to run, for example. “David loved 3-D,” Romberger said. But they couldn’t get the budget for it in the end, and the insets ended up on the back cover.

The third part was to be about David’s current life, but his feelings about what to include seemed to change from month to month. “All I had to go on were the conversations we had when we met,” Romberger said. “I tried to enact everything he said. He wanted me to draw him huge on Fifth Avenue smashing the buildings. That’s what he said. It seemed logical to make it St. Pat’s. But then, I couldn’t do the last part. He wanted it to end with a happy day—him just happy to be alive, but there’s nothing like that in his writing. His life dictated the ending.”

David would complain as he got sicker that if Romberger didn’t finish the thing, he was going to come back and haunt him.

He had begun to find places for objects he valued, like the baboon skeleton. At one of their last meetings, David gave Romberger his brown leather jacket. Romberger does not remember David saying anything about why he’d gifted him with this. “It was a significant thing. I mean, it’s his jacket. But how much do you want to question somebody,” said Romberger. “It was embarrassing. Here’s this fucking raggedy-ass leather jacket. It’s not like I was going to wear it.” He had the impression that David had been wearing it since he was a teenager.

Marguerite said, “He gave James the jacket, for posterity. Because it was symbolic.” David had told her that when he wore it, he could listen and watch unobserved. The jacket made him invisible.

On October 26, David gave his last reading. The evening at the Drawing Center was set up as a tribute to him and as a benefit for ACT UP’s needle-exchange program. Those who read selections from Close to the Knives included Kathy Acker, Karen Finley, Hapi Phace, and Bill Rice. David himself read a few selections not in the book, like “When I put my hands on your body …”

When Acker got up to read, she referred to David as “a saint.”

“That made me laugh,” Tom said, “but this was a big emotional event for him—and for the audience. He was very ‘up’ afterwards, very moved by it.”

Drawing Center director Ann Philbin, who had organized the event with Patrick Moore from ACT UP, wrote David a letter: “Thank you for providing the soul and spirit of one of the most extraordinary evenings I’ve spent in a long time. I’m sorry I burst into blubbering tears when I went to thank you at the end but I was one of hundreds walking around the room like a raw nerve. It was truly moving and I feel honored to have been there. How can anyone thank you enough for how you share what you know?”

David had decided on the other two images he wanted to use in the series with the skeleton piece When I Put My Hands on Your Body. As in that one, he would match a large black-and-white photo with silk-screened text.

He selected one of the many photos he’d taken over the years of bandaged hands. Gary Schneider made a large print, and over that, a silk screener printed the final section from David’s last completed text, “Spiral,” concluding with “I am disappearing but not fast enough.”

The third image looks like a Japanese temple guardian caught in a conflagration. It’s a very disordered scene, with a burnt shoji screen, lanterns on tilted poles, and piles of detritus in front of the guardian. Apparently the temple was not protected. David never completed a text for this.

On November 6, David flew to Minneapolis to perform ITSOFOMO at the Walker Art Center with Ben Neill. Jean Foos went along to be the “nurturing helping person,” as she put it. David had very low energy, and he had become “suspicious” of Neill. “For no reason,” Foos emphasized. (And Neill never knew this.) David was still struggling, in his isolation, with suspicion about many of the people close to him.

Then he was unhappy with his hotel and checked out after one night. He went to stay with Foos, at her sister’s house. The major drama that played out during four days there was David’s effort to get the sister’s Weimaraner to like him. The dog just didn’t take to David, which bothered him a great deal. Foos remembered that there was a lot of tension until the dog finally came around.

Patrick McDonnell drove up from Normal with his boyfriend and chauffeured them over the Twin Cities’ icy roads. They all went to see Isaac Julien’s Looking for Langston.

“David slept in a room in the theater building during the afternoon before the show,” Foos said. “I had to go get him up. There were many nervous moments wondering if he was up to it. But then he gave an amazing performance!”

Back in New York, David was still stuck in his depression, still morose. “It was sometimes hard to talk to him,” Tom said. “No matter what you said, it wasn’t good enough. I’m not quite sure what he was looking for. Then I’d get worked up and not know what to do and probably made it worse. It wasn’t until he had those two weekends …”

The first two weekends in December, David was running a fever of 106 degrees. Both weekends he called Tom in the middle of Friday or Saturday night to say, “Can you come over?” Tom arrived to find him not only running a high fever but also shivering violently. He stayed with David and did not sleep. When it happened the second time, Tom called the doctor, who said to take him to the hospital.

On Sunday, December 8, Tom took David to the emergency room at Cabrini, the hospital where Hujar had died. David, uninsured, was soon enrolled in Medicaid. Two days later, Tom left on a long-planned trip to Mexico with Anita and other friends. David had never wanted to go along. “I was just relieved because he was in a room, he was being cared for, he was comfortable,” said Tom. “He was actually happy to be in the hospital that first time.”

David spent a week in isolation because the doctor thought he might have tuberculosis. This was a precaution. Tests showed the problem to be pigeon TB, or MAI. Once David received this diagnosis, he was moved to the IV drug users ward—all AIDS patients—because that’s where there was a bed, and he called me. “Everything started falling apart lately,” he said. “I’m having invasive procedures.”

I went to see him. The guy in the next bed kept his television blaring around the clock, which was driving David nuts, but he said of the junkies on the ward, “They accepted me right away.” Remarkably, this hospitalization brought him back to his artist self. In a green journal he designated as “rough notes,” he started writing observations on the other patients. For example, “ ‘That was my best tattoo …’ shows me amputated stump ‘not much left—it was a dragon.’ All I could make out was a wing uttering from the wound.”

I went to see David again on Christmas Eve. That’s when I finally met Tom, who was seated next to the bed, learning from a nurse about how to administer antibiotics and total parenteral nutrition (TPN) through David’s newly implanted Hickman catheter. “It looks like a Christmas tree ornament,” David said, staring down at the thing in his chest.

David was cranky. The ward reeked of Elizabeth Taylor’s Passion for Men, which had been distributed to everyone as a gift, and it felt impossible to have a regular conversation amid the chaos and noise: TVs blasting, people shouting, carolers bumming everybody out. “It’s like trying to get better in a subway car,” he complained. “I’m going to write about this.”

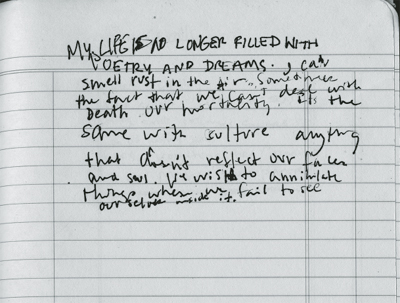

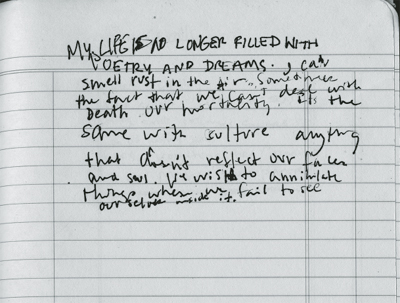

On his good days, he talked about working again. But he never again had enough energy. In the last entry in the journal of rough notes, added shortly after a line about the Elizabeth Taylor perfume, his handwriting is ragged. He wrote, “My life is no longer filled with poetry and dreams. I can smell rust in the air. Sometimes the fact that we can’t deal with death, our mortality—it’s the same with cultures—anything that doesn’t reflect our faces and soul. We wish to annihilate things when we fail to see ourselves inside it.”

Even here, in what I think of as the last journal entry, he felt compelled to connect his situation to the wider world. That had always been his style. His writing, his neo-Beat prosody, was built on the long breath that leaves one body to engulf the endless world and, returning, sees the universe in a single action. Call it a Howl.

“My life is no longer filled with poetry and dreams.” This last journal entry is undated but follows events he recorded on Christmas Eve, 1991.

(David Wojnarowicz Papers, Fales Library, NYU)

When David came home after Christmas, Tom decided that he’d better move into the loft. He would go home to feed his cats and get the mail, but he was now David’s principal caregiver. The upstairs neighbor Dori brought a mattress down for him, and they put it on the floor.

David asked a few people to come over for one day to help him go through his things. Among them was Norman Frisch. “He was obsessing about how he no longer knew where things were,” said Frisch, “and he was worried about things not getting to the right people after his death. He was in bed most of the time, giving instructions about what he wanted. Or maybe he was sitting at the kitchen table. People would bring stuff over to him and spread it out on the bed and he would decide what to keep or what went where. When it came down to it, there was very little that he was actually willing to part with.” He had piles of work prints, however. They were substandard, and he was afraid they could make it onto the market. Those were destroyed.

Given that he now had a catheter in his chest, he had to worry about infection. To that end, he had the friends take out the old terrariums. His scorpion was dead—no need for crickets. The loft was filthy but the friends did more sorting than scrubbing. One pile for journals and notebooks, another for film and video materials, another for anything related to Hujar.

Frisch remembered it being a very long day. “He was in rough shape—not entirely rational, very emotionally raw, easily overwhelmed, taking a lot of pain meds, sometimes drifting in and out.”

David still had high fevers and nausea. He would tell me later that his spleen was now so enlarged that it had pushed his intestines to one side. But in this interval, before the second hospitalization, he did not want me to come over.

Karen Finley saw him a couple of times during this period. She said, “He was very suspect. He actually got mad at me for coming over. He told me, ‘I don’t understand why you’re here. What do you want?’ He expressed anger. He gave me the ninth degree. He wanted to make sure I wasn’t coming over out of pity. Or, people could come over with their own issues about death and be gazing upon him.”

This was when she got to know Tom, whom she’d met for the first time the night of the reading at the Drawing Center.

David told Finley that he was very worried about his baby elephant skeleton. She promised him she’d take it. “He knew that I would take care of it, and that I could handle the heaviness of what that was,” Finley said. “I always saw it as an image really of him, of his totem. He’s the elephant. The elephant never forgets. You know—there’s the ancientness of it.”

David was doing so poorly that Tom was convinced he was close to death. He could remember sitting in a chair in the loft, crying while David slept.

On January 19, David called me. He was back in the hospital, on a quieter floor. “They lured me in, saying three days,” he said, “but I guess it’ll be ten.”

Tom had told David that, while he was at Cabrini, he was going to clean the loft. “I cannot sleep in this pigsty.”

David was resistant. He said, “I have things here.”

Tom promised he would throw nothing away. Not even a matchbook. He’d put everything in boxes.

“I finally convinced him to let me clean it up,” said Tom, “and I remember looking at the bed and, literally, the foam had taken on the shape of a body. It was a futon or something and it had almost an indentation from where Hujar had been. This was a platform bed, so he was basically lying on wood. I called David’s downstairs neighbor and we hauled it downstairs and threw it away.” Tom had a real mattress delivered and hired someone to build a headboard so David would be able to sit up in bed. Then he had shelves installed on the windows for flowerpots. Tom washed the floor and cleaned the disgusting stove.

David called me again on January 22. I had not been able to visit him because I had a cold and couldn’t risk bringing germs to someone with no immune system. He told me that he had a blood infection now. They’d pulled out the Hickman. “Just pulled it out. It’s scary how cavalier they are.” He had night sweats so bad that the bed would be soaked. They told him to drink water. “It takes hours to get my hand over to it,” he said. Now though, he had come to trust the doctor a lot more. “He’s on top of things.”

He asked Tom to call his half-siblings, Pete and Linda, to tell them he was in the hospital. From about this point until the end of David’s life, Pete and Linda and their spouses came to visit David nearly every weekend.

“I didn’t know who Tom was at that time,” Pete said. “Then David said, ‘He’s my boyfriend.’ And I said, ‘Well, do you trust him?’ And he goes, ‘I think so.’ I said, ‘Do you or don’t you? You gotta be sure.’ Then when I met Tom and I saw Tom—next time I talked to David, I said, ‘Why are you worried about him? The guy loves you.’ ”

David came home again on January 30, and his top priority was to get over to the Kitchen to see Karen Finley’s installation Memento Mori before it closed on February 1.

Finley’s work is about deep emotion, the feelings that propel someone to use a four-letter word because they can’t articulate what they really feel. In this case, she wanted to deal with grief about AIDS, addressed so inadequately at a typical memorial service, and with violence against women.

David went with Tom, Anita, and Philip Yenawine. At the entrance, they were each given a glass of wine at the Spit Bar, then led to a wall covered with flags from every country. An assistant there invited them to spit the wine onto the flag of their choice. The flags had begun to look like they were covered with blood.

David was given a chair and his friends moved it through the installation, allowing him to sit at each station. They came to the Ribbon Gate, where each took a ribbon and tied it to the gate in memory of a loved one who’d died of AIDS. The floor in the Memorial Room was covered with dead leaves. Here was the bedside vigil, illustrated by a volunteer in a bed and another in a chair next to it. Finley had written texts over the walls, “Lost Hope” and “In Memory Of.” In the corner was a mound of sand where they could place a lit candle in memory of someone. At the Carnation Wall, they pushed the stem of a flower through a hole in a lace curtain.

The Women’s Room addressed abortion rights and violence against women. Finley had written the texts “It’s My Body” and “My Own Memories” over these walls. In the corner was a mattress surrounded by dead leaves and flowers. A woman sat there, wrapped in sheets.

Finley told me later that David sat at the Spit Bar for a while and did all the rituals. He told her that being there made him feel human again. “I could tell that he forgot he was sick,” she said. “It broke my heart when I saw him reading everything on the walls. He was almost unable to walk.”

Afterward David wanted to go to Union Square Cafe for smoked shell steak, his favorite. When they got to the restaurant, they were told that dinner would not be served for another three hours. Knowing that David was too weak to make it to the loft and back, they sat there and waited the three hours.

I went to visit David at the loft early in February. He sat propped up with some pillows in a blue corduroy shirt. There was an image of an Indian chief on the blanket over his legs.

Tom injected him with some anti-nausea medication and made him chicken soup. Then he left to feed his cats. As soon as Tom left, David told me he was thinking about suicide. It was about quality of life, he said. He’d had two months of treatment with no improvement. Now they were talking about taking out his gall bladder and putting in another Hickman. He hated that “brutal” stuff. He said this as he injected antibiotics into the catheter in his arm, then hooked a small bottle to it. The bottle had what looked like a balloon inside, which would collapse as the medicine flowed out. “That’s for the MAI,” he said.

Tom had purchased a comfortable armchair, in case David wanted to get out of bed and sit in something besides a kitchen chair. The loft was still incredibly cluttered, with piles of paper everywhere. “I should just throw it all away,” he said.

When I saw David in the hospital at the end of January, he’d talked about making art again. He’d felt better. But on this occasion, he told me he could not remember feeling better.

He did have some good news, however. The rock band U2 planned to use his falling buffalo image for a record cover and a video. They were among the musicians on Red Hot and Blue, the first CD put out by the Red Hot Organization—founded by David’s friend John Carlin to raise money for organizations fighting AIDS. Carlin had sent the band a “Tongues of Flame” catalog, and they loved it.

On February 20, he called to tell me he couldn’t get on his feet. His legs were killing him. The doctor was thinking neuropathy, but David hoped it was just because he hadn’t exercised in so long. The week before, he’d been tottering at least. Now that he could no longer take for granted his ability to walk, he was afraid to be left alone.

I stopped by the loft to get keys from Tom so I could get in the next day and sit with David. He was lying on his side, and I got a look at his legs for the first time. Toothpicks.

I don’t know why he let me into his life at this point. There were many friends he wouldn’t see or even speak to on the phone, and in most cases, I also don’t know why he cut them off. He and I talked about death on those occasions when it was just the two of us. He was curious about Buddhism. Since I have close friends who are practitioners, I had attended many talks and ceremonies, even a public cremation. I shared what little I knew. He asked if I believed in reincarnation, admitting that the possibility bothered him: “I don’t want to come back,” he said.

He’d had a visit the day before from Adam Clayton, the U2 bassist. David had taken some Ritalin so he could feel up for that.y The day I was there, he had a doctor’s appointment and took more Ritalin—“hoping it would give me strength,” he told me. It hadn’t worked. He couldn’t even stand.

About a week later, Tom called to ask if I could stay with David for the day. Tom had been missing a lot of work. He always took care of what David needed first, so he sometimes went in late or not at all. When I arrived, David was sitting with his feet over the side of the bed, hunkered down, hooked up to the bottle of MAI medicine. I noticed that his elbows, feet, and knees were swollen. Probably from the steroids, he told me. The table next to his bed was entirely covered with pill bottles.

A physical therapist came to help David exercise. They walked once around the perimeter of the loft. The guy had David raise his arms out straight, parallel to the ground, five times. Then above his head five times. After that, David needed to sit down and rest. They repeated this routine three or four times. David paid the guy. He was relieved when he left. Three or four times that day, I massaged David’s feet. It helped, he told me. One of his legs was “two-thirds better.”

At the beginning of March, Pat came from Paris to visit. And Philip Zimmerman came from San Francisco. David seemed to rally around this time, meaning he actually went outside for a couple of short walks. But he still had depressed, anxious days and terrible nights.

Tom was getting exhausted. “One night I was just desperate to go home and be in my own apartment for a night’s sleep,” he said. Zimmerman said he would stay with David.

David spent the night writhing and groaning, emitting sounds like I EE I-EE and saying, “Oh god, please help me.” He had a fever, but every time Zimmerman approached him with a thermometer or a cold cloth, David’s rage would surface. “Always in the eyes,” said Zimmerman.

Around six thirty in the morning Zimmerman called Tom and said, “You’ve got to come over here. David hates me. He’s yelling at me. He doesn’t know who I am.”

Tom got dressed and walked over to the loft.

Zimmerman was standing against a wall in the kitchen, which was just a few feet from the bed where David sat scowling, “Who is this guy? What’s he doing here?”

Tom said, “David, that’s Philip. He stayed with you to take care of you.”

David said, “Oh!”

Clearly the virus had started its work on David’s brain, but at this point, he was still of sound mind most of the time.

On another occasion, though, Judy Glantzman spent the night with the same result: David in bed screaming, “Who are you? What do you want?”

Glantzman could not remember if she even stayed through the night. “It was so scary I couldn’t do it ever again.”

On March 18, U2 sent a limousine to the loft to bring David to the Meadowlands for their show, along with Tom and Pete and Linda—David’s “little brother and sister,” as he called them—and their spouses.

The band paired David’s falling buffalo photograph with what became one of their signature songs, “One.” They released it as a single with David’s image on the cover—with all royalties going to AIDS research.

At the Meadowlands, David and his entourage met the band backstage before the show. He was having a hard time walking that night. Bono asked David if he would like to pray with them. David declined. But everyone had been so kind. Pete and Linda were given seats near the side of the stage. The band had arranged for David to have a chair on the platform in the middle of the arena where the tech crew sat, controlling the sound and lighting. Tom stood behind him. As the band began to play “One,” the buffalo image came up on the screen behind the drum kit, and Bono called out, “David! This is for you!” Tom choked up.

Eventually, the band would pay for all of David’s private nursing costs.

He called me the day after the concert and said, “Parts were great, but it’s not my world. It really made me feel my age.”

Word was getting around that David was in bad shape.

Doug Bressler, the musician from 3 Teens who had worked with David on the soundtrack for A Fire in My Belly, had not seen David in quite awhile but just thought he was busy. “I didn’t know how bad his health was because he never talked to me about it,” said Bressler, who began to cry as he remembered this. One day Bressler ran into Steve Brown, who told him that David had dreamt about him. Specifically, David had dreamt that Bressler came to visit and flew in through the window. Brown added, “You better go see him. It’s bad.”

Ben Neill also came to visit. They had talked about doing a video documentary of ITSOFOMO with some of David’s film footage, parts of the live performance, and maybe some documentation from rehearsals. Neill told him that PBS’s Alive from Off Center had expressed interest. But David told him, “I can’t listen to it anymore.” He said what he really wanted was to go for a drive. Neill told him he had a car now. He could take him. David was enthusiastic, telling Neill, “Yeah, I want to take a ride. Let’s go somewhere.” But he was really too weak.

P.P.O.W sent someone over with the last finished piece—the imploring bandaged hands with the silk-screened text about “disappearing but not fast enough.” Penny Pilkington remembered, “He hardly had the energy to sign it.”

One day, he asked me if I thought he should contact his mother. Since I knew little about her at that point, I didn’t know what to tell him, but thought that if she didn’t already know what kind of shape he was in—how good could that relationship be?

Tom said that David told him one day, “I wish I had a mother.”

I kept a phone log for my calls at work. Just notes. One from David in April reads, “Threw up. No cat.” Tom told me that David decided he wanted a cat, and Tom was trying to give him what he wanted at this point. They took a cab to the ASPCA. “We found one that we both liked, but they told us it was a biter,” Tom said. David reconsidered. No cat. Tom was relieved. They cabbed it back to the loft. David struggled up the stairs and collapsed into bed.

Karen Finley came to the loft to pick up the baby elephant skeleton on May 4, the day David went into the hospital for the last time. He had endured two weeks of nonstop nausea. Tom woke up that day sick with a high fever. He felt awful, so Finley agreed to take David in.

When she got to the loft, David was “puking his guts out,” she said, and he looked terrible. She called the doctor, who arranged for an ambulette to pick him up. David was so out of it that when he put his jacket on he pulled out his catheter. He walked down the stairs bleeding everywhere, puking into a bag. A neighbor ran for paper towels to stanch the blood. As Finley stood with him on Second Avenue waiting for the ambulette, David could not remember what they were doing out there.

When the ambulette arrived, the driver refused to help David and drove wildly as the blood spurted everywhere. He claimed to not know where Cabrini was. When they got to the crowded emergency room, no one there would help either as David’s blood dripped on the floor. Finally, Finley told me, “I threw a hissy fit.” Someone then fixed his IV, but no one would clean him up. They handed Finley a towel. David was still puking into a bag. There was nowhere for him to sit. Finley said he looked like he’d passed to the other side.

By the next day, though, he was better. No more vomiting. Four bags of fluid on the IV stand. He had a south view this time. Once he was strong enough to stand up, he could see the roof of his building from the window. David did his last writing during this stay, which lasted for most of May. On a couple of pages torn from a notebook, he wrote “Hospital.” I won’t quote it all, but this seems most salient:

The world is way out there sort of in the distance vibrating and agitated like a bowl of gruesomeness. They shot me with Demerol and gave me a powerful sleeping pill and then started blood transfusions that took place all night long and I watched the dawn arrive among the southern view of the city. It was quite beautiful as plastic pack after plastic pack of other people’s blood emptied into my body. I wish I had language enough to speak what all this is to me. I’m losing my memory at an alarming rate. It’s been going on for months slowly at first and now accelerating. Events are lost to me seconds after they take place.

One of the horrors of the disease was its unpredictable course. There could even be moments that seemed like remission along the twisting but always downward spiral—and then there were the ghastly surprises. This time, after a week in the hospital, David’s feet swelled up to twice their normal size. He joked that he thought they might explode, that he could feel things breaking in there. He was staring at the awful things when I got to his room. Dr. Friedman walked in, looked like he had not expected to see this, and prescribed a diuretic.

Once medicated, David insisted on a trip to the smoking lounge, hobbling with one white-knuckled hand around his IV stand. He’d been hooked up to IVs or PICC lines for months, though he’d refused to let the doctor insert another Hickman catheter. “Too brutal.” But now he had track marks, which he showed me after we sat down in the cheerless nicotine den.

Somehow we got onto the subject of cameras. He told me Hujar had repeatedly tried to show him how to use his Leica, his street-shooting camera, but David could never get the hang of that stuff about F-stops and preferred his automatics. I told him I’d once had a Nikon F, but it was stolen from my apartment, and I’d never found another camera I liked as much. “Really?” he said. “I’ll give you that camera of Peter’s.” I was moved that he would offer such a thing, but did not expect him to remember our conversation. He was clearly losing his memory.

David was waiting for certain infections to clear up. Then, he told me, he would have his spleen and his gall bladder removed. The other person in the lounge, an old guy in a wheelchair, decided to butt in to say he’d just had his gall bladder removed too, and he had this incredible doctor. David, tottering and wincing his way to the bathroom, turned when this man mentioned the doctor’s name and said angrily, “That guy nearly killed a friend.” Once David was out of the room, the man in the wheelchair assured me that the doctor was good. His own T-cell count had risen from zero to seven.

When I came back to Cabrini a few days later, David was sleeping heavily. His upper and lower arms, where he used to have IVs, were wrapped in blue bandages. They were infected. I decided not to wait for him to wake up. Tom was there and walked me to the elevator. He told me that David was talking about suicide again. Because if this is all there is … Because if there’s no hope … Tom had convinced him to see how he felt after the surgery.

It was Tom’s presence that most reassured him now. Tom would enter the room, calling “Hi, handsome” and David would brighten. One day David told me, “I worry he’s going to spend the best years of his life taking care of me.”

David had surgery on May 22. Tom called me when it was over and said he thought David was going to be upset. “Because the cut was so big,” he said, and started to cry.

The next night David called Tom at eleven P.M. quavering, “They’re trying to kill me.” He was having a bad reaction to the morphine. Tom went to Cabrini and spent the night in the empty bed next to David’s.

I went to see him the day after that. He looked so tense, so vulnerable—eyes bugging out, body taut, tube up his nose, not able to say much. “You know what?” he said to me quietly, his voice breaking. “They had me on a five cc drip …” He was still getting the morphine out of his system. I took his hand and felt the pulse beating through it, hard and rapid.

A couple of days later, he had someone call me at work to make sure I was coming to the hospital that afternoon. He had something to give me. When I got there, he pulled Hujar’s Leica out from under the bedclothes. Overwhelmed, I stumbled through a thank you. “I figured you could do some stories where you did both the words and the pictures,” he said.

He had not remembered our earlier conversation about cameras, but he did remember that I was leaving town. I had taken a job in Los Angeles for the summer. Leaving David was my only regret. We did not say goodbye but spoke of how we were both sure we would see each other again. In hindsight, it looks like denial, but I don’t think I was the only one who expected him to at least live through the summer. Everything that could be done for an AIDS patient in 1992 was being done, and we all thought the surgery would buy him time.

Dr. Friedman explained that they had operated because “the spleen was enlarged and there could have been a rupture. We thought it was infected, that he had a splenic abscess and that we had to remove it as a focus of infection.” What they found, though, is that the MAI had spread through his intestines.

The last time I saw him at Cabrini, David told me that if he got a little better, he would come visit me in L.A. When he shuffled off to the bathroom, the nurse told me they were going to give him another Hickman, but hadn’t told him yet. This one would be “permanent.”

The day David left the hospital to go home, he had a talk with the doctor. “He was very clear about what he wanted,” Dr. Friedman said. “He told me, ‘I know that if I go back to the hospital one more time, I will die there. I want to die in my apartment. I want to die in that space.’ ”

David wanted to make sure that Peter Hujar was part of the photography collection at the Museum of Modern Art, and to that end, he donated four Hujar prints—probably right after he got home from the hospital. In a thank-you letter from the museum dated June 29, 1992, John Parkinson III, chairman of the Committee on Photography, said, “Artists often give their own work to the Museum, but it is much rarer that they give the work of others. Your generous gift has significantly enhanced our collection of Hujar’s work and I am pleased to thank you for it on behalf of the Committee and the Board of Trustees.”

One night as Tom lay on his mattress on the floor, David looked down at him and said, “You can sleep in the bed. Get in.”

“I thought the operation would make things better,” said Tom, “but he got sick pretty soon after coming home. Started throwing up black stuff.”

David and I still spoke on the phone. On June 22, David called me and said, “Something changed drastically. My brain.” Certainly, the dementia had been coming on for a while, but on this day, he felt some physical sensation he couldn’t describe beyond “everything’s strange, everything’s upside down.”

He was still following his self-imposed rule of not telling Tom the bad news, not discussing death with him. “He thought talking about death scared me,” said Tom, “and there were times when I didn’t want to talk about it, because I wanted to keep hope going.” So David did not tell Tom that he had felt something change in his brain. But Tom knew something was off. One night he cooked David one of his favorite meals, roast beef and broccoli, and they sat eating at the blue table. “He ate it but I could tell he was somewhere else,” Tom said. “He had this goofy look on his face.” Not a self-presentation Tom had ever seen before from David. Not the normal David.

One night Tom was sitting on the end of the bed, and David said, “I guess I’m not the star of this movie.”

Tom said, “You’re not a star in everything but you probably have a good cameo.”

Then David asked, “Do I die in this movie?”

Tom paused and then said, “Yes, I think you do.”

“How do I die?”

Tom replied, “How would you like to die?”

David looked alarmed, so Tom said, “How about quietly in your sleep.”

And David said, “Yeah, that’s OK.”

In Los Angeles on June 28, I saw part of the Gay Pride parade down Santa Monica Boulevard. It seemed to be at least 80 percent male and white, mostly tanned, buff guys who must have run right over from the gym and then a tiny contingent of pale, scrawny politicos with banners about AIDS. At least that was my impression. I couldn’t stand watching too much of this denial of reality. I went home and called David.

“All sorts of weird stuff is taking place,” he told me. “I don’t know what money I have and what I don’t have.” He told me he had just been away for a week and a half, driving. He’d done some work in Argentina. Then he went to Normal, where he’d slept in a barn. Contradicting him would have been pointless and cruel. So I asked him why he’d been sleeping in a barn.

“I was trying to do work. But I feel like I try to do too much. I’ve really been ripped off quite badly.” He went back to discussing Argentina, where he’d had a good time. “But I lost something. My direction. My focus. I did an installation at the home of an artist who died on the outskirts of Buenos Aires.”

“What was the installation about?”

“About money. About poverty.”

As David neared the end of his life, he worried constantly that he was going to end up back on the street, that he would run out of money. Tom told me that at one point David became convinced that nearly everyone he knew was stealing from him. In this phone call, David told me that he couldn’t find the check he’d just been given in Buenos Aires, but acknowledged, “I’ve been ill a bit, having trouble with my head.”

He asked me if I ever ran into Luis Frangella. I wasn’t quite sure where David thought I was. Luis had been dead for a year a half. I just said no. He told me that Luis was sick. If I went to Argentina, could I take him some money? “Of course,” I told him. David seemed relieved.

“I love you and think of you all the time,” I said.

“Vice versa,” he replied. “Is it horrible to say vice versa? Tom gets upset with me when I say that.”

I told him it was fine for me, but maybe in Tom’s case he could tell him he loved him.

“I have a hard time with those words,” said David. “I’ve had a hard time readjusting after my trip. I get lost sometimes and don’t know where I am. I’m sort of at a crossroads now. I don’t know how they’re going to treat this. I have so many ulcerations. I want to get things together here at home, pare things down. I’m not sure of anything except I gotta hang on. I could die but I may not feel much different till later, like in October or towards the end of the year.”

As we said our goodbyes, David told me that it had been great seeing me in Argentina.

Round-the-clock nursing care began during the last few weeks of David’s life.

Early in that phase, Tom woke one night and saw that David was not in the bed. He heard the shower. The night nurse was agitated but not doing anything. (And was soon replaced.) Walking into the bathroom, Tom saw David taking a shower. He was amazed that David had not only walked unaided to the bathroom but managed to step into the big claw-footed tub.

Tom said, “David, what’s going on?”

“I’m going to Times Square.”

“Ah, well, let me help you get dried off.”

As soon as David turned off the shower, he had to sit down on the edge of the tub. Tom wrapped a towel around him. David was almost too weak to stand, but Tom got him back into bed, and by that time he had forgotten about Times Square.

“There was one that got me the worst,” said Tom. “He was in bed and I was walking out, and he said, ‘Hey, how about if I meet you later at Union Square Cafe and we’ll have dinner?’ And it hit me. I’m never going to sit in a restaurant with him again.”

On June 30, David called me, sounding completely coherent and angry at the doctor. “They’re nuts! They want to put me on methadone. It’s really toxic,” he complained. “I don’t like what’s going on. If they leave me alone, I’ll be fine.” He told me that he would probably come see me before the end of the summer.

They had diagnosed another opportunistic infection, something that could be treated in the hospital. Tom’s first reaction was, yes, back to the hospital. (David had never told Tom that he didn’t want to be hospitalized again and wanted to die at the loft.) But, Tom said, “Looking at him, his mind was gone, and Bob [the doctor] seemed hesitant about it, and I realized that David wouldn’t understand, if he was there, why he couldn’t smoke. He wouldn’t know where he was. He would get scared. Then I finally decided. I told Bob no. But that was a hard decision. That was one of the last things before Bob and I agreed to cut off everything.”

Tom called me on July 3 to say that that night they were going to stop the nutrition, the TPN that David was getting through the Hickman. And that David wanted to see me. “It doesn’t make sense for him to live like this when all he does is lay in the bed and vomit,” Tom said. “The nausea is worse again, and it’s clear it won’t stop. It’s time to let his body take its own direction. What breaks my heart the most”—he began to sob—“is all he’s been through. I just don’t want him to suffer.”

Though David did not know about this decision, he had been clear that he didn’t want to hang on artificially. He said to Tom, “They tell me I’ll be taking care of a baby elephant pretty soon.”

I arrived back in New York on July 9 and went directly to the loft. Overcome with emotion, I was glad to find David asleep. Even his sleep seemed different, heavier. When he woke, he was surprised to see me. I told him I thought it was time for a visit. He didn’t question it. He was wearing a bright green T-shirt and orange swimming trunks. He was drugged, in pain, nauseated, and unable to focus. He could no longer sit up without help. He could no longer stand.

He had made for himself a kind of shrine. He’d hung a dozen necklaces on the wall next to his bed, each a different vivid color, thick and sparkly. This man who had dressed most often in jeans and a pocket T-shirt (to hold cigarettes) never wore jewelry, but he’d been collecting it for years. He’d bought charms on his travels, complex special ones, then strung them on a necklace. He gave this to Karen Finley. When he came home from the hospital for the last time, he hung the bright necklaces he’d bought at an Afghani store on Bleecker Street. Then he put on a silver bracelet and a silver necklace with an antique cross and a kachina doll charm. On his last trip out of the loft, he went to a jeweler with his day nurse and bought a solid gold necklace, thick with an Indian weave. He didn’t put it on but kept it near.

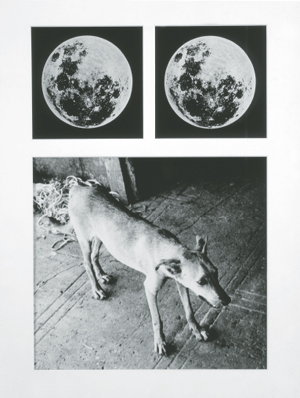

He still had the same artwork hanging on the wall. It had been there all through his illness—his Fever, two photos of the moon above a photo of a skinny anxious-looking dog that he’d taken in Mérida, at a slaughterhouse.

During the two and a half days I spent there, he slept most of the time. Every period of wakefulness ended with him vomiting into one of two plastic dishpans that were always on the bed. He repeatedly inquired about the Demerol pump attached to his Hickman. What was it? Steve Brown stopped by and David told him he was thinking about getting tattooed. “Something mythic but kind of contemporary. Machine but flesh.”

Fever, 1988–89. Three gelatin-silver prints on museum board, 31 × 25 inches overall. David had this piece hanging above his bed at home through at least the last six months of his illness. (Private collection)

He slept most of the next day but woke periodically to tell me something. He had just been to Queens, he said, “to see about that commotion. About God. All these people had had visions.” Tom explained later that it was a reference to the trip they’d made with Hujar in 1987 to find the healer, to find a cure.

At one point, David said to me, “I’m just trying to figure out where I am.”

“Home,” I told him.

He looked confused.

“Second Avenue and Twelfth Street,” I explained.

“Hujar’s place?”

He looked relieved. Later he lurched to a somewhat upright position and asked the nurse, “Is there a bathroom here?”

I met a friend for dinner and returned to find only the night nurse there with the sleeping David. I decided to wait for Tom to return. When he did, he told me he wasn’t sure what to do about funeral plans. He and David had never discussed it, and now it was too late. He’d thought about burying him near Hujar, but that was a Catholic cemetery. “I just wish I could hold him and make him better,” Tom said and began to cry.

Just then, David woke up, lucid and fully present for the first time that day. He smoked a few cigarettes and drank some water. Tom sat next to him on the bed. We chatted and David kept asking what time it was: ten ten, ten fifteen, ten twenty. Then he got tired and went back to sleep.

The next day, a Saturday, David woke up and asked Tom, “Can you find somebody to get me a diagnosis?” It made Tom cry.

There were many visitors that day, and I stayed away from the bed to give them privacy. Pat had arrived from Paris and was staying in New Jersey with their brother, Steven, whom David had not spoken to since 1989. Every day, Steven drove Pat to the loft but would not come in. Not out of rancor toward David. He was convinced that David did not want to see him, that David had rejected him permanently and would yell at him if he came upstairs. When Steven spoke later at David’s memorial, he said that basically he and David had played hide and seek and had played it too well and never found each other.

That day, David got a letter from his English publisher, Serpent’s Tail, with a copy of its cover for Close to the Knives. Tom began to read the letter out loud to him, choked up after a sentence, and handed it to me to finish. They were using Hujar Dreaming on the cover. David stared at it for a long time, loving how it looked with the green type and yellow background.

Did David even know that this was a book he’d written? A painting he’d made? We couldn’t quite tell anymore. But because it delighted him, and because he no longer had a short-term memory, Tom was able to bring it back every half hour or so, and say, “David, have you seen the English cover for your book?”

And David would look up in wonderment. “No!” Tom would get it back out. And David would love looking at it again.

He slept most of the time, however, sometimes clenching his fists, making faces. Sometimes he looked very old, but more often childlike and rather dazed. “Oh boy,” he’d say about the pain. I noticed how he accepted things, how he no longer asked questions like “Why can’t I stand up?” In his moments of lucidity, he described his condition as “not feeling too good.” I looked around at the clutter—the yeti on a trike; the crawling baby doll whose head had been replaced with an alligator’s; the plastic exploding volcano, kachinas, and dinosaurs; and the framed color photo of a duckling.

Around ten thirty or eleven P.M. David woke and Tom told him about all the people who had been there to see him that day. Apart from his sister Pat, he’d been visited by Brian Butterick, Judy Glantzman, Philip Yenawine, his stepbrother, Pete, and stepsister, Linda, and many others. David did not remember any of it. Tom asked him if he’d seen the English cover for his book. “No!” said David, and Tom pulled it out again. David stared again for quite a few minutes. This would always be new.

Then he got the hiccups. His whole stomach was spasming. None of the tricks that usually stop a hiccup attack had any effect. Finally he started to vomit, and the hiccups stopped. As if his stomach had been trying to throw up but didn’t have the strength. David looked down at the scar, healing nicely from the surgery done in May. He said sweetly to Tom, “What were they looking for?”

David had always wanted a ring with a green stone, and he’d found such a stone on one his trips to the Southwest. Tom asked him if he’d like that for a ring and had one made for him with 23 karat gold. “He was really very emotional when I gave it to him,” said Tom. “He was out of it, but I put it on his finger and he cried a little bit. Jean Foos was there, and she started to cry on the side. There were so many of those moments while he was sick.”

Philip Zimmerman came back from San Francisco, bringing David a turquoise bullet, and remembered him saying, “It would be great if it was made out of meteorite.”

Tom and Anita went to Redden’s Funeral Home “to pre-plan what had to happen,” as Tom put it. He was crying, so Anita gave them David’s name and spelled it wrong. Tom corrected it, and they both cried.

As David moved further into dementia, he finally dropped the burdens he had always carried. The rage. The anxiety. The emotional toxicity of his childhood. “At that phase of dementia, he was the happiest I ever saw him,” said Judy Glantzman. “He was delighted with life.” That might be the saddest thing I ever heard about David.

Back in Los Angeles, I called him on July 14. He actually took the call but sounded very weak. “I’m just feeling so-so,” he told me. That was the last time we spoke.

Patrick McDonnell came to visit from Illinois. One day David said that he wanted to sit by the window. Tom was there, with Patrick, Steve Brown, Philip Zimmerman, maybe others. David couldn’t walk at all, so they picked him up in a sheet, and David went, “Wheeee!”

“So we started to bounce him and he loved it,” said Tom. “He kept going, ‘Wheeee! Wheee!’ ”

One day soon after this, he went into a coma. He was suffering from what his doctor described as “overwhelming sepsis—probably bacterial sepsis with multiple infections, everything from disseminated candida, which is fungus, Mycobacterium avium, overwhelming HIV infection, Kaposi’s sarcoma, which manifested internally, and probably Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia.”

Judy Glantzman remembered lying on the bed next to him, telling him—since people in a coma can still hear: “David, if you need to go, it’s OK” and his face took on the old look of rage, as if to say, I’ll go when I’m ready.

David Wojnarowicz died of AIDS on July 22, 1992, at the age of thirty-seven.

This occurred at “Hujar’s place” at about nine thirty P.M. Present were Tom, Anita Vitale, Jean Foos, Steve Brown, Philip Zimmerman, and David’s siblings Pat, Peter, and Linda.

Once David was declared dead, Pat threw herself on the bed, hugging him and calling his name. She became so upset when the hearse arrived that Tom felt he had to stay with her instead of walking down the steps with David’s body.

Judy Glantzman had left to meet with her sister and so missed David’s passing, but returned about ten minutes later. When the hearse arrived, Steve Brown and Philip Zimmerman said they would carry David downstairs. Glantzman walked down with them.

As they walked out onto Second Avenue, with David in a body bag, there was one last surreal moment. The singer and composer Diamanda Galás happened to be walking by. She and David had never met, but they’d spoken once on the phone. She shared his commitment to addressing AIDS, in her case through The Plague Mass, which showcased her five-octave range and fierce persona.

Galás does not remember being on Second Avenue that night, but she made an indelible impression on Zimmerman and Glantzman. She had walked by, but as they were putting David into the hearse, she spun around and ran back, yelling, “Who is that? Is that David Wojnarowicz?” Zimmerman and Brown didn’t answer. What Glantzman remembers is that Diamanda Galás was there at the door, screaming. “As if our feelings were being amplified,” said Glantzman. “Hysterical screaming.”