AS SIMPLE AS THIS question sounds, and as obvious as the answer may seem to most of us, defining “orgasm” can prove difficult. In some ways, it is as difficult to define “orgasm” as it is to describe how something tastes.

Let’s begin to explore the meaning of the word orgasm by looking at its linguistic origin, the Greek word orgasmos, which is defined as “to swell as with moisture, be excited or eager” (Oxford English Dictionary). Alternatively, we could use the more technical definition offered in the Kinsey Reports: “The expulsive discharge of neuromuscular tensions at the peak of sexual response.” An even more technical description was offered by the research team of Masters and Johnson: “A brief episode of physical release from the vasocongestion and myotonic increment developed in response to sexual stimuli.”

Perhaps the most interesting of all characterizations is the one that was offered by John Money, who, with his colleagues, wrote the following description of orgasm: “The zenith of sexuoerotic experience that men and women characterize subjectively as voluptuous rapture or ecstasy. It occurs simultaneously in the brain/mind and the pelvic genitalia. Irrespective of its locus of onset, the occurrence of orgasm is contingent upon reciprocal intercommunication between neural networks in the brain, above, and the pelvic genitalia, below, and it does not survive their disconnection by the severance of the spinal cord. However, it is able to survive even extensive trauma at either end.”

So, what are orgasms? Here is our broad definition: an orgasm is a buildup of pleasurable body sensations and excitement to a peak intensity that then releases tensions and creates a feeling of satisfaction and relaxation.

NOBODY CAN REALLY FEEL someone else’s pleasure, so comparisons of the sort implied by this question are difficult to make. However, the following experiment was a clever way of getting at the question. Researchers Vance and Wagner, in 1976, asked college students to write descriptions of their own orgasms, and a group of judges tried to guess which descriptions were written by men and which by women. The judges were a mix of female and male obstetrician-gynecologists, psychologists, and medical students. Before submitting the descriptions to the judges, the researchers substituted gender-neutral words for gender-specific words in the students’ written descriptions (such as genitalia for penis or vagina) to intentionally conceal the sex of the writers.

The researchers found that the judges were “unable to distinguish the sex of a person from that person’s written description of his or her orgasm.”

The students’ descriptions are vivid, as demonstrated by the following quotations, selected at random from the responses of six of the forty-eight participants in the study:

One reason that men and women may experience similar feelings during orgasm is related to two of the primary body parts involved in orgasm: the penis and clitoris. These body parts are homologous, meaning that they both originate from the same tissue in the developing embryo. Throughout life, the spinal cord and brain are connected to the penis and clitoris by the same nerve route—the pudendal nerve (actually, a pair of pudendal nerves). So, while we don’t know the answer to the question with certainty, there are reasons to suspect that orgasms may feel generally similar for men and women.

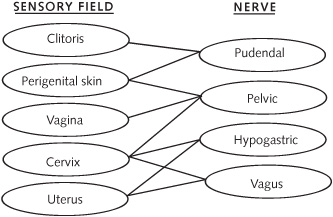

GENITALS ARE CONNECTED TO several different pairs of nerves, with each pair of nerves servicing (that is, carrying nerve impulses from) a different part of the person’s genital areas. Stimulating different combinations of the nerves produces different combinations of sensations. Depending on the parts of the genitals that are stimulated and the relative intensity and pattern of the stimulation, orgasms may feel very different from one time to another.

Nerves carrying information between the female genital regions and the brain. Each of the four named nerves is a pair of nerves--one on the left side, one on the right. Some genital regions use more than one pair of nerves to communicate with the brain, as shown by the connecting lines in the diagram. Three of the nerve pairs (the pudendal, pelvic, and hypogastric) travel to the spinal cord, where the sensations are then transmitted to the brain. The pair of vagus nerves, however, travel directly to the brain, bypassing the spinal cord.

For a woman, the sensory quality of an orgasm depends on where the stimulation occurs: the clitoris, vagina, or cervix. The clitoris is connected mainly to the pudendal nerves, the vagina mainly to the pelvic nerves, and the cervix mainly to the hypogastric, pelvic, and vagus nerves. Although stimulating each of these genital regions may by itself produce orgasms, the combined stimulation of two or three regions has an additive effect, producing a more encompassing orgasm, or what is described as “blended orgasm.”

In a man, the pudendal nerves carry nerve impulses from the penile skin and scrotum, and the hypogastric nerves carry nerve impulses from the testicles and prostate gland. So, stimulation of these two nerve groups may cause somewhat different feelings.

For many people, their “erogenous zones” extend beyond the genitals. The location of these zones is amazingly diverse and highly individualistic. Stimulation of an individual’s “personal erogenous zones” can greatly affect the intensity of his or her orgasms. In addition to sensory factors, orgasms are often affected by cognitive, psychological, and pharmacological factors—such as distraction, worry, relaxation, medications, and the like.

ORGASMS THAT OCCUR IN close succession, within a few seconds to a few minutes apart, are often referred to as “multiple orgasms.” Although there is no consensus among researchers about what defines multiple orgasms, we do know that some individuals experience orgasms multiple times in a relatively brief period. Multiple orgasms are more frequently discussed in relation to women’s sexual responses, but men can experience them as well. Indeed, as early as 2968 BC, in China, there were writings that described men’s multiple orgasms.

THE WORDANORGASMIA MEANS “a lack of orgasm.” This condition occurs in both men and women.

In men, anorgasmia is usually called “male orgasmic dysfunction,” and both biological (“organic”) and psychological factors may contribute to this condition. The current definition of male orgasmic dysfunction is “a spectrum of disorders ranging from delayed ejaculation to complete inability to ejaculate (‘anejaculation’), and retrograde ejaculation.” Any disease, drug, or surgical procedure that interferes with the normal functioning of the brain, spinal cord, or nerves can result in male orgasmic dysfunction. One of the main classes of drugs that inhibit orgasm is the SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), which are commonly prescribed for depression.

Women’s anorgasmia, or “orgasmic disorder,” is defined as “either a lack of orgasm, markedly diminished intensity of orgasmic sensations or marked delay of orgasm from any kind of stimulation.” Professionals in the field classify female anorgasmia into three types: primary, secondary, and situational anorgasmia. The diagnosis of “primary anorgasmia” applies to a woman who has never experienced an orgasm by any means of stimulation. “Secondary anorgasmia” refers to the case in which a woman was previously orgasmic but currently is anorgasmic. “Situational anorgasmia” relates to the conditions under which a woman may or may not experience orgasm—such as being able to experience orgasm by masturbation but not with a partner. According to researcher Raymond Rosen, anorgasmia is a common problem that affects an estimated 24 to 37 percent of women.

Therapy for anorgasmia includes a combination of a check-up by a medical professional (reviewing the history of medications and conducting necessary tests) and the use of “behavioral therapies.” Behavioral strategies have proven very effective for both men and women. Such strategies include “sensate focus exercises” (to gradually build up one’s comfort with intimate physical contact), directed masturbation (that is, masturbation under the advice of a therapist) with or without a vibrator, Kegel exercises (to strengthen the muscles of the pelvic floor), and physical therapy. Other issues that may cause anorgasmia and that may be treated by behavioral therapy include anxiety, a past history of sexual abuse or trauma, problems in communication with the sexual partner, and issues of trust of the partner.

The simplest, and perhaps most helpful, treatment for the largest number of people who experience anorgasmia may be for health care providers to ask questions and offer information. Orgasms can be elicited from a variety of body regions, including the penis, clitoris, vagina, G spot, cervix, prostate, nipples, breasts, anus—as well as through visual and auditory stimulation and mental imagery. Here’s an important point: while you can be stimulated erotically by your partner, your partner can’t “give” you an orgasm. You are in control of your own feelings, including your orgasms. And even if you don’t experience an orgasm, you can nevertheless derive great pleasure and satisfaction from a positive sexual encounter.

ALTHOUGH MOST PEOPLE CAN experience orgasms fairly often by the age of ten to fifteen, there is some debate as to when a person is first able to experience an orgasm. In the past half-century, numerous psychologists and anthropologists have described a wide array of sexual responses in children, including orgasm. Indeed, children of both sexes often explore their genitals, and such tactile self-stimulation can cause muscle reactions that are difficult to distinguish from orgasm in adult subjects. However, no well-controlled studies—that is, no rigorously conducted scientific studies—on children’s sexual responses, including orgasm, have been reported in recent years. The nerve (neural) network needed for many sexual responses is present and functional from the time of early childhood, and penile erection can even occur in the human fetus (that is, within the uterus). However, when young boys experience what seem to be orgasm-like responses, these responses are not accompanied by ejaculation, which requires the presence of androgens (such as testosterone), sex hormones that are not present in sufficient quantities for ejaculation before puberty.

MANY STUDIES ON AGING and sexual behavior have found a clear pattern of an overall decline of sexual function beginning when people enter their thirties or forties, but some people can experience orgasms past the age of ninety. As they age, both men and, more often, women experience the loss of their lifelong sexual partner due to death or illness, a loss that often leads to a decrease in sexual activity.

Some studies suggest that, for women, the ability to become sexually aroused remains as the individual ages. However, many women experience declines of desire, frequency of intercourse (coitus), and frequency of orgasm as they age (often well in advance of menopause). In a recent study of older women (average age was eighty-one years), only 18 percent were still sexually active, mainly by masturbation. There is good evidence that when older women have sexual problems, some of the causes are related to decreases in the secretion of the sex steroids—estrogen and androgen. For example, vaginal dryness and a condition known as dyspareunia (painful intercourse) are due to low levels of estrogen (which is correctable by vaginal estrogen therapy).

Sexual function and orgasm frequency also decline in men as they age. However, a typical older man (average age in the eighties) is twice as likely to be sexually active as a woman of a similar age (41 percent of men versus 18 percent of women). The most common type of sexual disorder in older men is erectile dysfunction.

A comparable pattern of sexual decline and disorder accompanying aging has been observed in nonhuman animals. For example, very old rabbits still attempt to copulate despite erectile dysfunction, and they will copulate successfully after receiving Viagra.

DURING SEXUAL INTERCOURSE, THE amount of time before reaching orgasm varies considerably among individuals. Factors such as age, sexual experience, and certain drugs influence the time it takes to reach orgasm. Both men and women can voluntarily delay orgasm through a variety of techniques. For example, in some practices of Hinduism—such as Tantra, which puts great emphasis on sexual intercourse for religious purposes— techniques developed over hundreds of years allow some individuals to control ejaculation and orgasm. In recent years, these techniques have been incorporated into practices in the western world, through a series of books that promote increased sexual satisfaction (see, for example, books by Kenneth Ray Stubbs).

Men typically require two to ten minutes of intercourse to reach orgasm. Men who experience “delayed orgasms” may need an hour or more of stimulation. Researcher Manfred Waldinger and his colleagues proposed that men who have early (premature) ejaculation and those who have delayed ejaculation are just extremes of the normal range of variability. They proposed that any random group of men will include some with early ejaculation (occurring within two minutes of starting sexual intercourse) and others with delayed ejaculation (requiring more than one hour of active intercourse). So, lifelong early or delayed ejaculators are considered to be part of the natural variability that occurs in any population. A common characteristic of many, but not all, rapid and delayed ejaculators is their lack of control of the ejaculatory latency. By contrast, a man who is near average for the duration of intercourse before orgasm may be more capable of controlling his ejaculation.

Several studies have found that most women require a more prolonged period of stimulation before orgasm. While some women have an orgasm within thirty seconds of starting self-stimulation, most women experience orgasm after twenty minutes.

ALTHOUGH THE TIME IT takes a person to reach orgasm is highly variable for both men and women, the duration of orgasm itself is less variable, and is shorter. In one study, women’s orgasms were found to last, on average, about eighteen seconds, and men’s orgasms lasted about twenty-two seconds. However, in 1966, Masters and Johnson found that the duration of orgasm in women is typically about three to fifteen seconds, while orgasms in men are shorter. Multiple factors are known to influence how long an orgasm lasts, such as age, period of sexual abstinence, type of sexual stimulation, and whether the orgasm is a result of masturbation or sexual intercourse. With aging, there is a tendency for the duration of orgasms to decrease.

THE FREQUENCY OF ORGASM and attitudes toward the frequency vary greatly among individuals and cultures. Some societies have recommended restraint in sexual activity for men, because ejaculation was considered debilitating; but other societies have considered sexual activity highly beneficial for vigor and health. Researcher Havelock Ellis, in 1910, surveyed historical and religious pronouncements on the appropriate frequencies of marital coitus (and presumably orgasm) for men, and he reported the following recommendations:

Typically, couples have more orgasms the younger they are. Kinsey reported that men had an average intercourse frequency of four times per week when they were fifteen to twenty years of age, three times per week at age thirty, twice per week at age forty, and less than once per week at age sixty. However, studies show that some men between the ages of sixteen and thirty experience as many as twenty-five orgasms per week.

A “refractory period” just after orgasm occurs in most men, a period when they can’t have another orgasm—although some men can experience multiple orgasms. A report of one such case documented six successive orgasms (with decreasing volume of semen) in less than forty minutes. The duration of the “recharge time” seems to depend on age, sexual partner, and sexual experience. The brain mechanisms involved in the refractory period have been extensively studied in laboratory animals. In laboratory rats, ejaculation is accompanied by release of the neurotransmitter GABA (gamma amino-butyric acid) from neurons (nerve cells) in the brain, a process that inhibits the activity of neurons that control sexual motivation. The neural basis for the refractory period in humans is not known.

In 1994, a study based on interviews of 436 partnered women in the United Kingdom investigated the occurrence of female orgasm during the prior three-month period. There was a clear relationship between a woman’s age and the likelihood that she experienced orgasm during a sexual encounter. Of the women thirty-five to thirty-nine years old, 63 percent reported experiencing orgasms during more than half of or all of their sexual interactions with their partner. Only 21 percent of women fifty-five to fifty-nine years old reported this frequency. Five percent of the younger women, but 35 percent of the older women, had not experienced an orgasm in the past three months. The intermediate age groups were intermediate in frequency of orgasm.

ONE WAY OF TESTING whether a behavioral trait, of any sort, has a genetic basis—or in other words, whether it is to some extent inherited—is to compare identical twins and fraternal twins. Identical twins have the same genetic makeup, because they come from the same fertilized egg. By contrast, fraternal twins develop from two different fertilized eggs and therefore are as different from each other as are two non-twin siblings; they just happen to be born at the same time.

Researchers use the reasoning that if a particular behavioral trait occurs much more frequently in both identical twins than in both fraternal twins, then there is probably a genetic component to the trait. Of course, that evidence alone doesn’t explain how the genes affect the trait. In one study that looked at whether there is a genetic basis to women’s orgasms, Kate Dunn and her colleagues reported the responses to questionnaires from almost 1,400 women in the TwinsUK study group. About half of the women were identical twins and half were fraternal twins. There was considerable variability in the frequency of their orgasms during intercourse or masturbation. However, the identical twins were much more similar in their frequency of orgasm than were the fraternal twins. The authors stated: “We found that between 34% and 45% of the variation in ability to orgasm can be explained by underlying genetic variation, with little or no role for the shared environment (e.g., family environment, religion, social class, or early education). These heritability findings are in a similar range (35-60%) to other behavioural and complex traits such as migraine, blood pressure, anxiety or depression.”

This conclusion is similar to that of Khytam Dawood and her colleagues, based on a questionnaire study of more than 2,000 women identified in the Australian Twin Registry. These researchers concluded that “overall, genetic influences account for approximately 31% of the variance of frequency of orgasm during sexual intercourse . . . and 51% . . . during masturbation.”

ORGASMS CHARACTERISTICALLY RESULT FROM genital stimulation, but there are many accounts suggesting that nongenital stimuli can also generate feelings that have been described, by both men and women, as orgasms. Here is a partial list:

St. Teresa of Avila. Shown here is a detail of Ecstasy of St. Teresa, by the seventeenth-century sculptor Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini. St. Teresa of Avila is said to have been able to enter trances in which she described an ecstatic state of rapture and sweet pain in feeling union with God. The description and the facial expression shown here are similar to those characterizing orgasm, suggesting to some (but refuted by others) that she may have experienced nongenital orgasms. (Photograph courtesy Terry Ginesi)

THE PARTS OF THE brain and spinal cord that control pain and orgasm overlap. This close association has some interesting consequences. For example, on the positive side, during orgasm produced by vaginal self-stimulation, women become half as sensitive to pain as they normally are (when at rest). In some cases, when surgeons were called upon to stop pain that could not be controlled by medication, they cut specific neural pathways in the spinal cord to stop the pain; as a result, however, the patients’ orgasms also became blocked. Sometimes the surgery was only effective temporarily, and the pain returned six months later—but, then, so did the ability to experience orgasms!

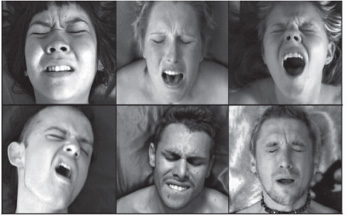

Examination of brain activity during orgasms or during experimentally induced pain shows that at least two brain regions—the insular cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex—are active during both experiences. This raises an intriguing but as yet unanswered question: How exactly does the brain distinguish between pain and pleasure, and what is the difference between the neurons that create the sensation of pain and those that create the sensation of orgasm?

Pleasure or pain? Pain and orgasm share a curious similarity of facial expression. Two of the brain regions that are activated by pain are also activated during orgasm, perhaps accounting for the similarity of expression. (Photographs courtesy Richard Lawrence)

Could the two brain regions have some property that is common to both pain and pleasure, perhaps the same intense emotional expression (controlling the contorted facial expressions that occur during both painful anguish and impending orgasm), but separate from the different feelings of pain versus pleasure? It seems possible. Perhaps the pain and pleasure pathways carrying sensation through the spinal cord and brain stream along together, producing similar effects on arousal and facial expression before diverging somewhere in the brain to pass the message either to a pain-sensing part of the cortex or to a different, pleasure-sensing part of the cortex. Until this divergence occurs, perhaps the sensory activity from either the genital or the noxious stimulation passes to the brain region that generates facial expression—so that the expression is curiously similar under both conditions.