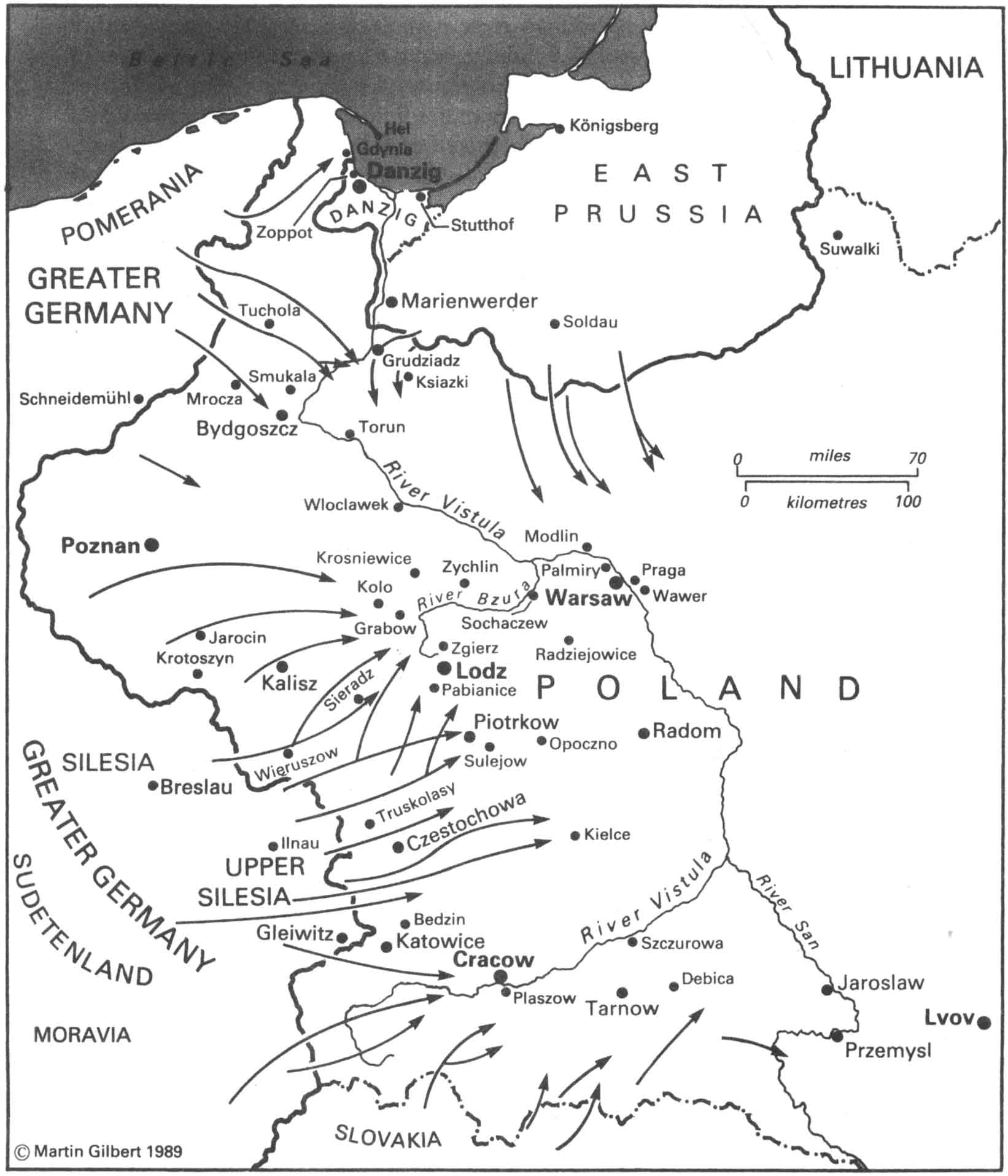

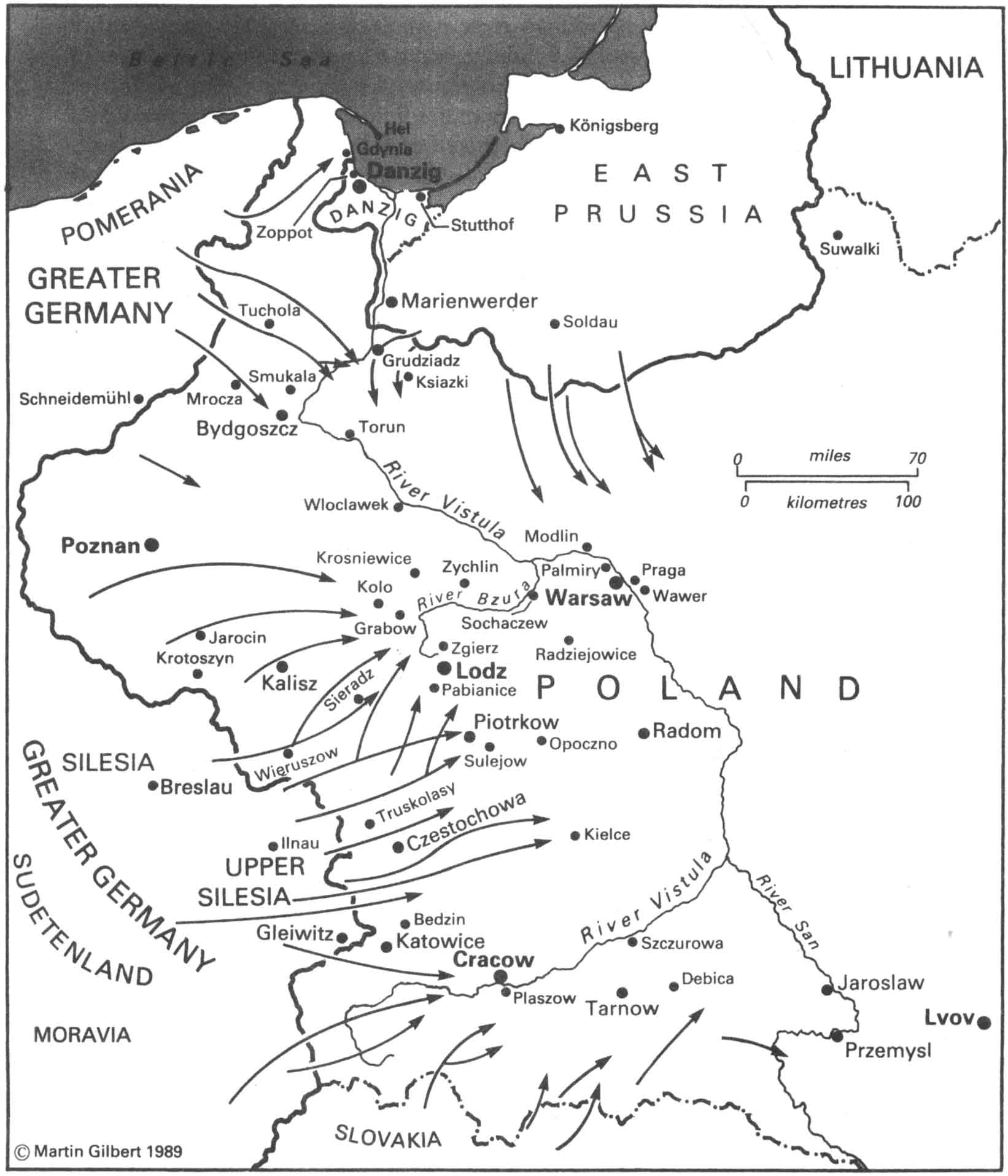

The German invasion of Poland, September 1939

The Second World War was among the most destructive conflicts in human history; more than forty-six million soldiers and civilians perished, many in circumstances of prolonged and horrifying cruelty. During the 2,174 days of war between the German attack on Poland in September 1939 and the surrender of Japan in August 1945, by far the largest number of those killed, whether in battle or behind the lines, were unknown by name or face except to those few who knew or loved them; yet in many cases, perhaps also numbering in the millions, even those who might in later years have remembered a victim were themselves wiped out. Not only forty-six million lives, but the vibrant life and livelihood which they had inherited, and might have left to their descendants, were blotted out: a heritage of work and joy, of struggle and creativity, of learning, hopes and happiness, which no one would ever inherit or pass on.

Inevitably, because they were the war’s principal sufferers, it is the millions of victims who fill so many of these pages. Many of them can be, and are, named; it is they, and the unnamed men, women and children whose tragedy is the bitter legacy of the war. There is courage, too, in these pages; the courage of soldiers, sailors and airmen, the courage of partisans and resistance fighters, and the courage of those who, starving, naked and without strength or weapons, were sent to their deaths.

Who was the first victim of a war that was to claim more than forty-six million victims? He was an unknown prisoner in one of Adolf Hitler’s concentration camps, most probably a common criminal. In an attempt to make Germany seem the innocent victim of Polish aggression, he had been dressed in a Polish uniform, taken to the German frontier town of Gleiwitz, and shot on the evening of 31 August 1939 by the Gestapo in a bizarre faked ‘Polish attack’ on the local radio station. On the following morning, as German troops began their advance into Poland, Hitler gave, as one of his reasons for the invasion, ‘the attack by regular Polish troops on the Gleiwitz transmitter’.

In honour of the SS Chief who had helped to devise the Gleiwitz deception, it had been given the code name Operation Himmler. On that same evening of August 31, the Soviet Union, Germany’s ally of less than a week, had finally been victorious in its battle with the Japanese on the Soviet—Mongolian borderlands, as Soviet forces, commanded by General Zhukov, destroyed the last resistance of the Sixth Japanese Army at Khalkhin Gol. As one war ended, another began, known to history as the Second World War.

The German advance into Poland on 1 September 1939 was not a repeat of the tactics of the First World War of 1914–18. Then, infantrymen, advancing towards each other until caught in a line of trenches, had mounted a series of attacks against a well dug-in enemy. Hitler’s method was that of ‘Blitzkrieg’—lightning war. First, and without warning, air attacks destroyed much of the defender’s air force while it was still on the ground. Second, bombers struck at the defender’s road and rail communications, assembly points and munitions dumps, and at civilian centres, causing confusion and panic. Third, dive-bombers sought out columns of marching men and bombed them without respite, while at the same time aircraft machine-gunned civilian refugees as they sought to flee from the approaching soldiers, causing chaos on the roads, and further impeding the forward movement of the defending forces.

Even as the Blitzkrieg came out of the sky, it also came on land; first in wave after wave of motorized infantry, light tanks and motor-drawn artillery, pushing as far ahead as possible. Then heavy tanks were to drive deep into the countryside, bypassing cities and fortified points. Then, after so much damage had been done and so much territory traversed, the infantry, the foot soldiers of every war, but strongly supported by artillery, were to occupy the area already penetrated, to deal with whatever resistance remained, and to link up with the mechanized units of the initial strike.

Twenty-four hours after the German attack on Poland, an official Polish Government communiqué reported that 130 Poles, of whom twelve were soldiers, had been killed in air raids on Warsaw, Gdynia, and several other towns. ‘Two German bombers were shot down, and the four occupants arrested after a miraculous escape,’ the communiqué noted, ‘when forty-one German aircraft in formation appeared over eastern Warsaw on Friday afternoon. People watched a thrilling aerial battle over the heart of the city. Several houses caught fire, and the hospital for Jewish defective children was bombed and wrecked.’

On the morning of September 2, German aircraft bombed the railway station at the town of Kolo. At the station stood a train of civilian refugees being evacuated from the border towns of Jarocin and Krotoszyn; 111 of them were killed.

Hitler’s aim in invading Poland was not only to regain the territories lost in 1918. He also intended to impose German rule on Poland. To this end, he had ordered three SS Death’s Head regiments to follow behind the infantry advance, and to conduct what were called ‘police and security’ measures behind the German lines. Theodor Eicke, the commander of these three Death’s Head regiments, explained what these measures were to his assembled officers at one of their bases, Sachsenhausen concentration camp, on that first day of war. In protecting Hitler’s Reich, Eicke explained, the SS would have to ‘incarcerate or annihilate’ every enemy of Nazism, a task that would challenge even the ‘absolute and inflexible severity’ which the Death’s Head regiments had learned in the concentration camps.

The German invasion of Poland, September 1939

These words, so full of foreboding, were soon translated into action; within a week of the German invasion of Poland, almost 24,000 officers and men of the Death’s Head regiment were ready to embark on their task. On the side of one of the railway carriages taking German soldiers eastward, someone had written in white paint: ‘We’re off to Poland to thrash the Jews.’ Not only Jews, but Poles, were to be the victims of this war behind the war. Two days after Eicke had given his instructions to the Death’s Head regiments, Heinrich Himmler informed SS General Udo von Woyrsch that he was to carry out the ‘radical suppression of the incipient Polish insurrection in the newly occupied parts of Upper Silesia’. The word ‘radical’ was a euphemism for ‘ruthless’.

Whole villages were burned to the ground. At Truskolasy, on September 3, fifty-five Polish peasants were rounded up and shot, a child of two among them. At Wieruszow, twenty Jews were ordered to assemble in the market place, among them Israel Lewi, a man of sixty-four. When his daughter, Liebe Lewi, ran up to her father, a German told her to open her mouth for ‘impudence’. He then fired a bullet into it. Liebe Lewi fell down dead. The twenty Jews were then executed.

In the weeks that followed, such atrocities became commonplace, widespread and on an unprecedented scale. While soldiers fought in battle, civilians were being massacred behind the lines.

On the afternoon of September 3, German bombers attacked the undefended Polish town of Sulejow, where a peacetime population of 6,500 Poles and Polish Jews were swelled by a further 3,000 refugees. Within moments, the centre of the town was ablaze. As thousands hurried for safety towards the nearby woods, German planes, flying low, opened fire with their machine guns. ‘As we were running to the woods’, one young boy, Ben Helfgott, recalled, ‘people were falling, people were on fire. That night the sky was red from the burning town’.

On 3 September, Britain and France both declared war on Germany. ‘The immediate aim of the German High Command’, Hitler told his commanders, ‘remains the rapid and victorious conclusion of operations against Poland.’ At nine o’clock that evening, however, a German submarine, the U-30, commanded by Julius Lemp, torpedoed the British passenger liner Athenia, which it had mistaken for an armed ship. The Athenia, which was bound for Montreal from Liverpool, had sailed before Britain’s declaration of war, with 1,103 passengers on board. Of the 112 passengers who lost their lives that night, twenty-eight were citizens of the United States. But the American President, Franklin Roosevelt, was emphatic when he broadcast to the American people on September 3: ‘Let no man or woman thoughtlessly or falsely talk of America sending its armies to European fields. At this moment there is being prepared a proclamation of American neutrality.’

Confident of a swift victory, on the evening of September 3, Hitler left Berlin on board his special train, Amerika, in which he was to live for the next two weeks amid the scenes and congratulations of his first military triumph. The British Government, meanwhile, had put into operation its ‘Western Air Plan 14’, the dropping of anti-Nazi propaganda leaflets over Germany. On the night of September 3, thirteen tons of leaflets were flown, in ten aircraft, across the North Sea and across the German frontier, to be dropped on the Ruhr; six million sheets of paper, in which the Germans were told: ‘Your rulers have condemned you to the massacres, miseries and privations of a war they cannot ever hope to win’.

Britain’s first bombing raid over Germany took place on September 4, as German troops continued to advance into Poland behind a screen of superior air power. That day, ten Blenheim bombers attacked German ships and naval installations at Wilhelmshaven. No serious damage was done to the ships, but five of the bombers were shot down by German anti-aircraft fire. Among the British dead was Pilot Officer H. B. Lightoller, whose father had been the senior British officer to survive the sinking of the Titanic before the First World War.

In Britain, morale was boosted by the news of this raid on German warships. ‘We could even see some washing hanging on the line,’ the Flight Lieutenant who had led the attack told British radio listeners. ‘When we flew on the top of the battleship,’ he added, ‘we could see the crews running fast to their stations. We dropped our bombs. The second pilot, flying behind, saw two hit.’ Both the Flight Lieutenant and the reconnaissance pilot were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

The British pilots were under orders not to endanger German civilian life. At that point in the war, such orders seemed not only moral, but capable of being carried out. The German commanders had given no such orders. ‘Brutal guerrilla war had broken out everywhere,’ the German Quartermaster General, Eduard Wagner, wrote on September 4, ‘and we are ruthlessly stamping it out. We won’t be reasoned with. We have already sent out emergency courts, and they are in continual session. The harder we strike, the quicker there will be peace again.’ That striking came both on land and from the air. At Bydgoszcz, on 4 September, more than a thousand Poles were murdered, including several dozen boy scouts aged between twelve and sixteen. They had been lined up against a wall in the market place—and shot. Entering Piotrkow on September 5, the Germans set fire to dozens of Jewish homes, then shot dead those Jews who managed to run from the burning buildings. Entering a building which had escaped the flames, soldiers took out six Jews and ordered them to run; five were shot down, the sixth, Reb Bunem Lebel, died later of his wounds.

Many towns were on fire in Poland that week; thousands of Poles perished in the flames, or were shot down as they fled. Two wars raged simultaneously; one on the battle front of armed men, and the other in towns and villages far behind the front line. At sea, also, a war had begun, the course of which was to be savage and all-encompassing. That 5 September, German submarines sank five unarmed merchant ships, four British and one French. The British had not been slow to respond; HMS Ajax, in action that day, sank two German merchant ships ‘in accordance with the rules of warfare’, as Britain’s First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, informed his War Cabinet colleagues. The merchant ships had failed to stop when ordered to do so.

Each day saw the rules of war ignored and flouted by the Germans, as they advanced deeper and deeper into Poland. On September 6, in the fields outside the Polish village of Mrocza, the Germans shot nineteen Polish officers who had already surrendered, after fighting tenaciously against a German tank unit. Other Polish prisoners-of-war were locked into a railwayman’s hut which was then set on fire. They were burned to death. Henceforth, prisoners-of-war were not to know if the accepted rules of war, as laid down by successive Geneva Conventions, were to apply to them: the rules whereby the Nazis acted were completely at variance with those which had evolved over the previous century.

For the Jews, it seemed that extremes of horror were to be perpetrated by this conqueror who boasted that the Jews would be his main victim. Speaking in Berlin seven months before the outbreak of war, Hitler had declared that, if war broke out, ‘The result will not be the Bolshevization of the earth, and thus the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe.’ Six days of war had already shown that the murder of Jews was to be an integral part of German conquest. In a gesture of defiance, Dr Chaim Weizmann, the elder statesman of the Zionist movement, wrote to the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, to declare that the Jews would fight on the side of the democracies against Nazi Germany; his letter was published in The Times on September 6. That day, Hitler was driven by car from his special train to the battlefield at Tuchola, where a Polish corps was surrounded. While he observed the scene of battle, a message reached him that German forces had entered the southern Polish city of Cracow.

The war was one week old; Cracow, a city of more than 250,000 inhabitants, was under German control. On the following day, September 7, the SS chief Reinhard Heydrich told the commanders of Eicke’s special SS task forces, which were about to follow behind the advancing soldiers: ‘The Polish ruling class is to be put out of harm’s way as far as possible. The lower classes that remain will not get special schools, but will be kept down in one way or another.’ Eicke himself directed the work of these SS units from Hitler’s headquarters train, and it was on the train on September 7 that Hitler told his Army Commander-in-Chief, General von Brauchitsch, that the Army was ‘to abstain from interfering’ in these SS operations. Those operations were relentless. On the day after Hitler’s talk with Brauchitsch, an SS battalion executed thirty-three Polish civilians in the village of Ksiazki; such executions were soon to become a daily occurrence.

Hitler’s entourage quickly learned what he had in mind. On September 9 Colonel Eduard Wagner discussed the future of Poland with Hitler’s Army Chief of Staff, General Halder. ‘It is the Führer’s and Goering’s intention’, Wagner wrote in his diary, ‘to destroy and exterminate the Polish nation. More than that cannot even be hinted at in writing.’

Britain and France saw little scope for military action to assist Poland in any substantial way. On September 7, French military units crossed the German frontier at three points near Saarlouis, Saarbrücken and Zweibrücken. But no serious clash of arms took place. The Western Front was quiet. In London, a specially created Land Forces Committee of the War Cabinet discussed the scale of Britain’s future military effort. At its first meeting, on September 7, Churchill, the new First Lord of the Admiralty, proposed the creation of an army of twenty divisions by March 1940. ‘We must take our place in the Line’, he said, ‘if we are to hold the Alliance together and win the War.’ In its report on the following day, the Land Forces Committee set out, as the basis for Britain’s military planning, that the war would last ‘for at least three years’. The first twenty divisions should be established within the next twelve months, a further thirty-five divisions by the end of 1941. Meanwhile, the main thrust of Britain’s war effort would of necessity be defensive: September 7 saw the inauguration of the first two convoys of merchant ships, escorted by destroyers, one from the Thames estuary, through the English Channel and into the Atlantic, one from Liverpool into the Atlantic.

That day, near the western Polish industrial city of Lodz, the last of the Polish defenders were still seeking to bar the German advance. Their adversaries, SS fighting troops, noted how, that afternoon, at Pabianice, ‘the Poles launched yet another counter-attack. They stormed over the bodies of their fallen comrades. They did not come forward with their heads down like men in heavy rain—and most attacking infantry come on like that—but they advanced with their heads held high like swimmers breasting the waves. They did not falter’.

It was not lack of courage, but massively superior German artillery power, which, by nightfall, forced these defenders to surrender. Pabianice was lost. The road to Lodz was open.

Inside Germany, those who had opposed the pre-war excesses of Nazism were equally critical of the attack on Poland. But the threat of imprisonment in a concentration camp was a powerful deterrent to public criticism. Before the war, thousands of Germans had fled from tyranny. Once war began, escape became virtually impossible, as Greater Germany’s frontiers were sealed and mounting restrictions imposed on movement and communications. The six months that had passed since the German occupation of Bohemia and Moravia in March 1939 had enabled the Gestapo system to be extended throughout the annexed regions. Two once-independent European capitals, Vienna and Prague, both suffered ruthless Nazi control, with all criticism punished and all independence of spirit crushed. The outbreak of war saw no slackening in the arrest of opponents of the regime; on September 9, Gestapo records show that 630 Czech political prisoners were brought by train from Bohemia to the concentration camp at Dachau, just north of Munich. Few of them were to survive the harsh conditions of work and the brutal treatment.

The speed of the German advance in Poland now trapped soldiers and civilians. In the Poznan sector, nineteen Polish divisions—virtually the same number of troops which Britain wished to have ready for action in March 1940—were surrounded; in the ensuing battle on the River Bzura, 170,000 Polish soldiers were taken prisoner.

Behind the lines, the atrocities continued. At Bedzin, on September 8, several hundred Jews were driven into a synagogue, which was then set on fire. Two hundred of the Jews burned to death. On the following day the Germans cynically charged Poles with the crime, took a number of hostages, and executed thirty of the hostages in one of the main public squares. On September 10 General Halder noted in his diary that a group of SS men, having ordered fifty Jews to work all day repairing a bridge, had then pushed them into a synagogue and shot them. ‘We are now issuing fierce orders which I have drafted today myself,’ Colonel Wagner wrote in his diary on September 11. ‘Nothing like the death sentence! There’s no other way in the occupied territories!’

One eye-witness to this killing of civilians was Admiral Canaris, head of the Secret Intelligence Service of the German Armed Forces. On September 10 he had travelled to the front line to watch the German Army in action. Wherever he went, his Intelligence officers told him of ‘an orgy of massacre’. Polish civilians, they reported, having been forced to dig mass graves, were then lined up at the edge of the graves and mown down with machine gun fire. On September 12, Canaris went to Hitler’s headquarters train, then at Ilnau in Upper Silesia, to protest. He first saw General Wilhelm Keitel, Chief of the Armed Forces High Command. ‘I have information’, Canaris told Keitel, ‘that mass executions are being planned in Poland, and that members of the Polish nobility and the Roman Catholic bishops and priests have been singled out for extermination.’

Keitel urged Canaris to take the matter no further. ‘If I were you’, he said, ‘I would not get mixed up in this business. This “thing” has been decided upon by the Führer himself.’ Keitel added that, from that moment on, every German Army command in Poland would have a civilian chief alongside its military head. This civilian would be in charge of what Keitel called the ‘racial extermination’ programme. A few moments later Canaris saw Hitler, but said nothing. Shaken by all that he had learned, he returned to Berlin, his allegiance to Hitler much weakened. One of those who had been opposed to Hitler since 1933, Carl Goerdeler, formerly Mayor of Leipzig, told a fellow opponent of Nazism that Canaris had returned from Poland ‘entirely broken’ by Germany’s ‘brutal conduct’ of the war.

What Keitel had referred to as the programme of ‘racial extermination’ was given another name by those who carried it out. On September 13, the day after Canaris’s visit to Hitler’s train, one of the SS Death’s Head divisions, the Brandenburg Division, began what it called ‘cleansing and security measures’. These included, according to its own report, the arrest and shooting of large numbers of ‘suspicious elements, plunderers, Jews and Poles’, many of whom were killed ‘while trying to escape’. Within two weeks, the Brandenburg Division had left a trail of murder in more than thirteen Polish towns and villages.

The focus of the battle now turned to Warsaw, against which German bombers had been striking with considerable ferocity. Indeed, one of the points of protest raised by Canaris with Keitel had been the ‘devastation’ of the Polish capital. On September 14 the bombing was particularly severe. For Warsaw’s 393,000 Jews, one third of the city’s inhabitants, it was a holy and usually happy day in their calendar, the Jewish New Year. ‘Just as the synagogues were filled,’ a Polish eye-witness noted in his diary, ‘Nalewki, the Jewish quarter of Warsaw, was attacked from the air. The result of this bombing was bloody.’ That day, German forces entered the southern Polish city of Przemysl, on the River San, where 17,000 citizens, one third of the total population, were Jews. Forty-three of the leading Jewish citizens were at once arrested, savagely beaten and then shot, among them Asscher Gitter, whose son, like so many sons of Polish Jews, had emigrated to the United States, hoping that one day his father would join him. That day in the town of Sieradz, five Jews and two Poles were shot; in Czestochowa, the German civil administration ordered all Jewish industrial and commercial property to be handed over to ‘Aryans’, irrespective of whether its owner had fled the city or remained; in Piotrkow, a decree was issued forbidding Jews to be in the streets after five o’clock in the afternoon; the twenty-seven year old Getzel Frenkel, returning to his home five minutes after five, was shot dead for this breach of the decree.

The Polish Army, fighting tenaciously, was in retreat, its routes to eastern Poland bombed without respite. East of Przemysl, on September 14, a Polish officer recalled how, after his infantry division had retreated across the River San, German aircraft ‘raided us at frequent intervals. There was no shelter anywhere; nothing, on every side, but the accursed plain. The soldiers rushed off the road, trying to take cover in the furrows, but the horses were in a worse plight. After one of the raids we counted thirty-five dead horses.’ That eastward march, the officer wrote, ‘was not like the march of an army; it was more like the march of some Biblical people, driven onward by the wrath of Heaven, and dissolving in the wilderness.’ On the following morning, at Jaroslaw, Hitler himself watched while German forces crossed the River San in close pursuit.

Hitler’s generals, with the Polish Army in disarray, proposed that Warsaw, now surrounded, should be starved into submission. But Hitler rejected the notion of a long, or even a short, siege. The Polish capital was, he insisted, a fortress; it should be bombed and bombarded into submission.

***

The Polish Army, struggling to escape the German military thrust and air attacks, had hopes of regrouping in the country’s eastern regions, and in particular around Lvov, the principal city of Eastern Galicia. But in the early hours of September 17 these hopes were dashed. Unknown to the Poles, unknown even to Hitler’s own generals, a secret clause in the Nazi—Soviet non-aggression Pact of 23 August 1939, created a demarcation line across Poland, east of which the Soviet Union could take control. That September 17, the Soviet Foreign Minister, Vyacheslav Molotov, in a statement issued in Moscow, declared that the Polish Government had ceased to exist. As a result, he said, Soviet troops had been ordered to occupy eastern Poland. The Poles, so desperately engaged in seeking to defend themselves from the German onslaught, had no means of effective resistance.

Two Soviet Army groups now moved up towards the demarcation line. A hundred miles before they reached it, they met German troops who, at considerable cost, had fought their way into Poland’s eastern regions. Those Germans withdrew, handing over to Russians the Polish soldiers whom they had taken prisoner. In Lvov, it was a Soviet general who ordered the Polish troops to lay down their arms. They did so, whereupon they were surrounded by the Red Army and marched off into captivity. Thousands of other Poles were captured by the advancing Russian forces. Other Poles surrendered to the Russians, rather than risk falling into German hands. In Warsaw, the battle continued, with heavy loss of Polish civilian life as the bombs fell without respite. That night, in the Atlantic Ocean, the British suffered their first naval disaster; the loss of 518 sailors on board the aircraft carrier Courageous, torpedoed off the south-west coast of Ireland by the German submarine, U-29, commanded by Lieutenant Schuhart. The head of the German Submarine service, Admiral Dönitz, wrote in his diary of ‘a glorious success’. For Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty, it was a dire reminder of the perils of the war at sea, for he had already seen, during the First World War, how nearly the German submarines had choked Britain’s food and raw-material lifeline.

In Britain, the fate of Poland distressed those who had seen the two Western allies unable to take any serious counter-initiative. ‘Poor devils!’ one Englishman wrote to a friend in America on September 18, ‘they are magnificent fighters, and I think we all here have an uneasy feeling that, since they are our allies, we ought—at whatever cost—to have made such smashing attacks on the Western Front as to divert the Germans. I imagine that why we have not done so is that neither we nor France have enough machines yet in hand’.

The Germans were confident that no British or French move would impede their imminent victory. On September 18, British radio listeners heard for the first time the nasal tones of William Joyce, quickly nicknamed ‘Lord Haw-Haw’, broadcasting to his fellow countrymen from Berlin to tell them that the war was lost—less than a month after he had renewed his British passport. Just north of Berlin, at Sachsenhausen concentration camp, on September 18, Lothar Erdman, a distinguished German journalist and pre-1933 trade unionist, having courageously protested about the ill-treatment of his fellow prisoners, was savagely kicked and beaten, suffering severe internal injuries, from which he died.

In Warsaw, the defenders refused to accept the logic of German power. A Polish doctor, joining a group in search of medicines on September 18, found some in the cellar of a medical store which was already under German artillery bombardment. Also in the cellar was a German spy, a man who had lived in Poland for the past twelve years. He was caught with a miniature wireless transmitter, sending messages to the German siege headquarters. ‘After brief formalities,’ the doctor noted, ‘he was despatched “with greetings to Hindenburg”.’

By September 19 Warsaw had been under artillery bombardment for ten consecutive days. So many thousands of Poles had already been killed by air as well as by artillery bombardment that the public parks were having to be used for burials. Tenaciously, the Polish forces struggled to hold the city’s perimeter. Several German tanks were immobilized when they penetrated too swiftly into the suburbs. German troops, advancing too far, were captured. But the bombardment was relentless. ‘This morning’, one police officer noted in his diary on September 19, ‘a German bomber dropped a bomb which hit a house, not far from my headquarters, which I had converted into a temporary prison for about ninety Germans captured during last night’s fighting. Twenty-seven of them were killed.’

While Warsaw bled under bombardment, the first British troops, an army corps, landed in France. But no action was envisaged for it. The Western Front remained firmly on the defensive; quiet and passive. Meanwhile, north of Warsaw, Hitler made a triumphal entry into the Free City of Danzig, which had been detached from Germany at the insistence of the victorious powers at the end of the First World War. The crowd which greeted him were hysterical with joy. ‘It was like this everywhere,’ Hitler’s chief Army adjutant, Rudolf Schmundt, explained to a recent recruit to the Führer’s staff, ‘in the Rhineland, in Vienna, in the Sudeten territories, and in Memel. Do you still doubt the mission of the Führer?’

Addressing the citizens of Danzig on September 19, Hitler spoke of ‘Almighty God, who has now given our arms his blessing’. He also spoke mysteriously, and for Britain and France ominously, when he warned: ‘The moment might very quickly come for us to use a weapon with which we ourselves could not be attacked’.

***

From Danzig, Hitler moved to a hotel at the holiday resort town of Zoppot. There, to a group which included his personal physician, Dr Karl Brandt, the head of his Party Office, Philipp Bouler, and the Chief Medical Officer of the Reich, Dr Leonardo Conti, he set out his plans for the killing of the insane inside Germany itself. The purity of the German blood had to be maintained. Dr Conti doubted whether, medically speaking, there was any scientific basis for suggesting that any eugenic advantages could be produced through euthanasia. But the only serious discussion was about the quickest and least painful method of killing. Backdating his order to September 1, Hitler then gave Bouler and Brandt ‘full responsibility to enlarge the powers of certain specified doctors so that they can grant those who are by all human standards incurably ill a merciful death, after the most critical assessment possible of their medical condition’.

The operational centre of the euthanasia programme was to be a suburban house in Berlin, No. 4 Tiergartenstrasse. It was this address which gave its name to the organization itself, known henceforth as ‘T.4’. Its head was the thirty-seven year old Werner Heyde, Professor of Neurology and Psychiatry at the University of Würzburg, who had joined the Nazi Party at its moment of political triumph in 1933. Henceforth, the mental asylums were to be combed for those who could be given ‘a merciful death’. In the words of one Nazi euthanasia expert, Dr Pfannmüller, ‘The idea is unbearable to me that the best, the flower of our youth, must lose its life at the front, in order that feebleminded and asocial elements can have a secure existence in the asylum.’

From the first days of Operation T4, particular attention was paid to young children, and especially to newborn babies. At Görden near Brandenburg, a state paediatric institution established a Special Psychiatric Youth Department to which children were sent from all over Germany, and killed. One of its aims, a doctor who worked there later recalled, was ‘to put newborns to sleep as soon as possible’, in order specifically to prevent ‘closer bonds between mothers and their children’.

The euthanasia programme had begun. At Görden, and at six other institutions throughout Germany, those Germans judged insane were put to death. During the first two years of the war, tens of thousands were to perish in this way, the victims of perverted medical science.

In Poland, the Special Task Force troops of the SS had continued the killing of Jews in more and more towns as they came under German control. On September 20 the Operations Section of the German Fourteenth Army reported that the troops were becoming uneasy ‘because of the largely illegal measures’ taken in the Army’s area by the task force commanded by General von Woyrsch. The fighting soldiers were particularly angered that the SS men under von Woyrsch’s command, instead of fighting at the front, ‘should be demonstrating their courage against defenceless civilians’. Field Marshal von Rundstedt immediately announced that von Woyrsch’s SS Task Force would no longer be tolerated in the war zone, and that the anti-Jewish measures already under way in the Katowice area should cease.

The crisis which had arisen between the professional, fighting soldiers and their SS counterparts could not be resolved. But far more ambitious plans were now being prepared. On September 21, Reinhard Heydrich summoned the commanders of all SS units in Poland to an emergency conference in Berlin. Those commanders who could not be present were sent a secret note of the discussion. The ‘ultimate aim’ of German policy to the Jews must, he said, be kept ‘strictly secret’ and would take ‘a prolonged period of time’. Meanwhile, and as a prerequisite of this ‘ultimate aim’, Polish Jews were henceforth to be concentrated in a number of large cities. Jews living outside these cities, and in particular all Jews living in western Poland, were to be deported to those cities. Western Poland must be ‘cleared completely of Jews’. All farmland belonging to Jews should be taken from them and ‘entrusted to the care’ of local Germans, or even of Polish peasants. Once deported to the cities, the Jews would be confined to one particular quarter, forbidden to enter the rest of the city. In each city a council of Jewish elders was to be charged with ensuring that German orders about the movement of Jews were carried out on time. In case of ‘sabotage of such instructions’, these Jewish Councils were to be theatened with ‘the severest measures’.

Heydrich’s plan to recreate in the twentieth century the medieval concept of the ghetto was intended merely as a first ‘stage’ toward what he and his SS colleagues called ‘the final solution of the Jewish question’. This plan led to no halt, however, in the Special Task Force killings which had already provoked German Army protests; on September 22, the day after Heydrich’s conference, the SS Brandenburg Division arrived in Wloclawek, where it began what it called a ‘Jewish action’ lasting four days. Jewish shops were looted, the city’s synagogues blown up, dozens of leading Jews rounded up and shot. Even as this ‘action’ was in progress, Eicke instructed the Division’s commander to send two of his battalions to Bydgoszcz to conduct a further ‘action’ against Polish intellectuals and municipal leaders. As a result of this instruction, eight hundred Poles were shot on September 23 and September 24, less than three weeks after the first mass random killings in the city.

The first day of the renewed killings of Poles in Bydgoszcz was also the holiest day in the Jewish calendar, the Day of Atonement. To show their contempt for Jews and Poles alike, the German occupation authorities in Piotrkow ordered several thousand Polish prisoners-of-war, among them many Polish Jews, into the synagogue, and, forbidding them access to lavatories, forced then to relieve themselves in the synagogue itself. They were then given prayer shawls, the curtains from the Holy Ark, and the exquisitely embroidered ornamental covers of the Scrolls of the Law, and ordered to clean up the excrement with these sacred objects.

On the day of the perpetration of this disgusting, puerile order, another order, sent from Berlin to all German warships, led to an intensification of the war at sea. It was an Admiralty decree that any British or French merchant ship making use of its radio once it had been stopped by a U-boat should be either sunk or taken in prize.

German and Soviet troops now faced each other along the Polish demarcation line agreed upon by Ribbentrop and Molotov a month earlier. Only in the city of Warsaw, in the town of Modlin just north of the Vistula, and on the Hel peninsula near Danzig, were the Poles still refusing to surrender. ‘The merciless bombardment continues,’ a Polish officer in Warsaw noted in his diary on September 25. ‘So far German threats have not materialized. The people of Warsaw are proud that they did not allow themselves to be frightened.’ They were also on the verge of starvation. ‘I saw a characteristic scene in the street today,’ the officer added. ‘A horse was struck by a shell and collapsed. When I returned an hour later only the skeleton was left. The meat had been carved off by the people living near by.’

On September 25 the Germans launched Operation Coast, an air attack on Warsaw by four hundred bombers, dive-bombers and ground-attack aircraft, supported by thirty tri-motor transport planes. It was these latter which, dropping a total of seventy-two tons of incendiary bombs on the Polish capital, caused particularly widespread fires, havoc and human destruction. A Polish officer’s wife, Jadwiga Sosnkowska, who later escaped to the West, remembered, a year later, ‘that dreadful night’, when she was trying to help in one of the city’s hospitals. ‘On the table at which I was assisting, tragedy following tragedy. At one time the victim was a girl of sixteen. She had a glorious mop of golden hair, her face was delicate as a flower, and her lovely sapphire-blue eyes were full of tears. Both her legs, up to the knees, were a mass of bleeding pulp, in which it was impossible to distinguish bone from flesh; both had to be amputated above the knee. Before the surgeon began I bent over this innocent child to kiss her pallid brow, to lay my helpless hand on her golden head. She died quietly in the course of the morning, like a flower plucked by merciless hand’.

That same night, Jadwiga Sosnkowska recalled, ‘on the same deal table, there died under the knife of the surgeon a young expectant mother, nineteen years of age, whose intestines were torn by the blast of a bomb. She was only a few days before childbirth. We never knew who her husband and her family were, and she was buried, a woman unknown, in the common grave with the fallen soldiers.’

The citizens of Warsaw were at the end of endurance. Even the determination of 140,000 soldiers could not sustain them much longer. Wild rumours began to circulate, the last resort of those who were desperate. It was said by some that a Polish general was on his way from the East at the head of Soviet troops. Others claimed that they had seen Soviet aeroplanes, marked with the hammer and sickle, in actual combat with German aircraft over the city. In reality, Soviet aircraft are marked, not with the hammer and sickle, but with five-pointed red stars. Such a detail was irrelevant however, as rumours of rescue spread.

Not rescue, but a renewed German military assault, was imminent. On the morning of September 26 General von Brauchitsch ordered the German Eighth Army to attack. That evening, the Polish garrison commander asked for a truce, but von Brauchitsch refused. He would accept only a complete surrender. The city fought on. That day, in Berlin, at a conference held in the strictest secrecy, German scientists discussed how to harness energy from nuclear fission. It was clear to them that a substantial explosive power was possible. A ‘uranium burner’ would have to be made. Considerable quantities of heavy water would have to be distilled, at considerable expense. Excited at the prospect of a weapon of decisive power, the German War Office agreed to sponsor the necessary, and complex experiments. Whatever funds were needed would be made available.

***

At two o’clock on the afternoon of September 27, Warsaw surrendered; 140,000 Polish soldiers, more than 36,000 of them wounded, were taken into captivity. For the next three days, the Germans made no effort to enter the city. ‘They are afraid’, a Polish officer wrote in his diary, ‘to march their soldiers into a city which has no light and no water and is filled with the sick and the wounded and the dead.’

Hundreds of wounded Polish soldiers and civilians died who might have been saved, had medical help been offered to them. But this was not the German plan or method; by the day of Warsaw’s surrender, Heydrich was able to report, with evident satisfaction: ‘of the Polish upper classes in the occupied territories only a maxiumum of three per cent is still present’. Once more, words were used to mask realities: ‘present’ meant ‘alive’. Many thousands, probably more than ten thousand, Polish teachers, doctors, priests, landowners, businessmen and local officials had been rounded up and killed. The very names of some of the places where they had been held, tortured and killed were to become synonymous with torture and death: Stutthof near Danzig, Smukala camp near Bydgoszcz, the Torun grease factory, Fort VII in Poznan, and Soldau camp in East Prussia. In one Church diocese in western Poland, two-thirds of the 690 priests had been arrested, of whom 214 had been shot. Poland had become the first victim of a new barbarism of war within war; the unequal struggle between military victors and civilian captives.