The German invasion of Western Europe, May 1940

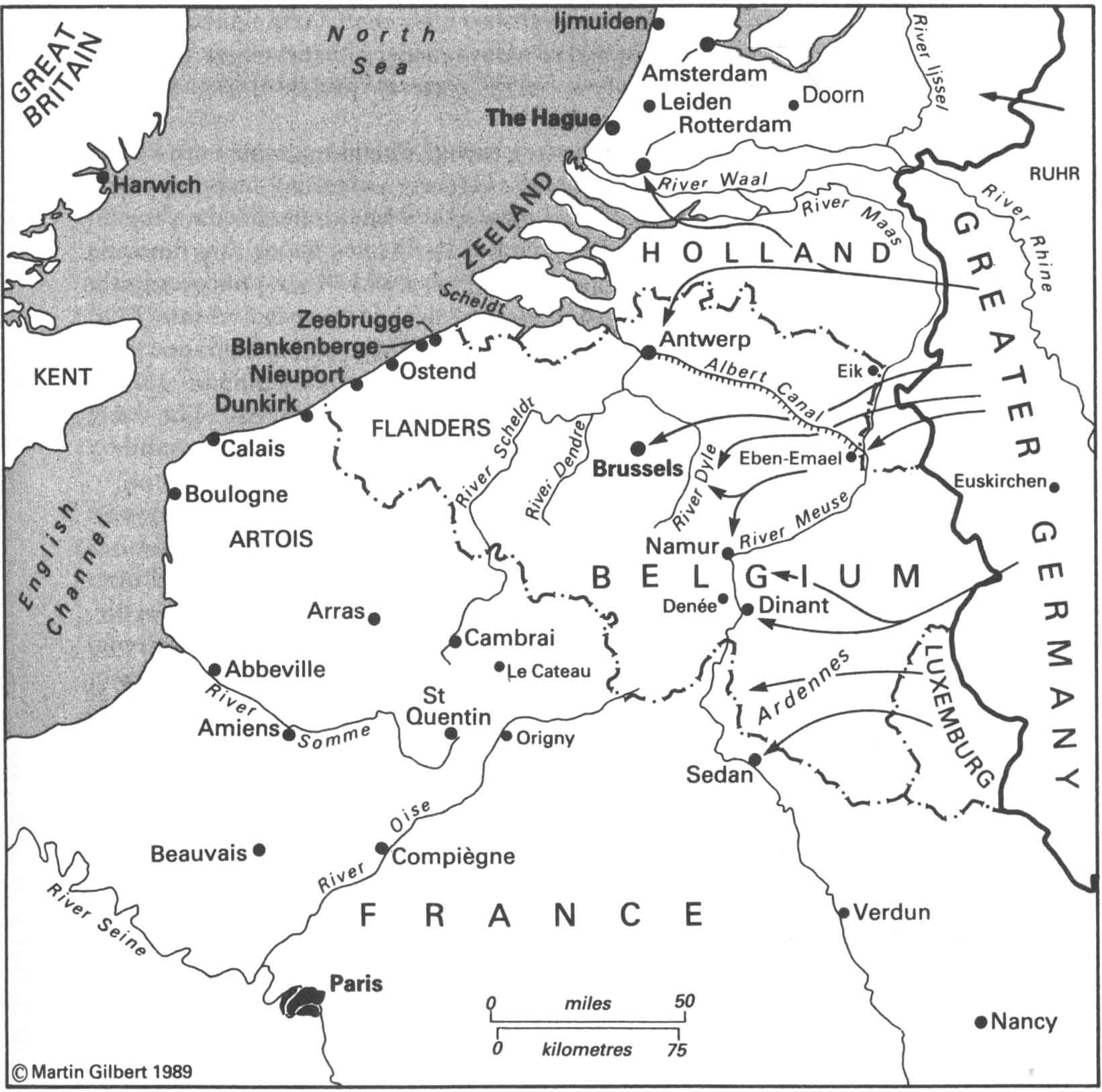

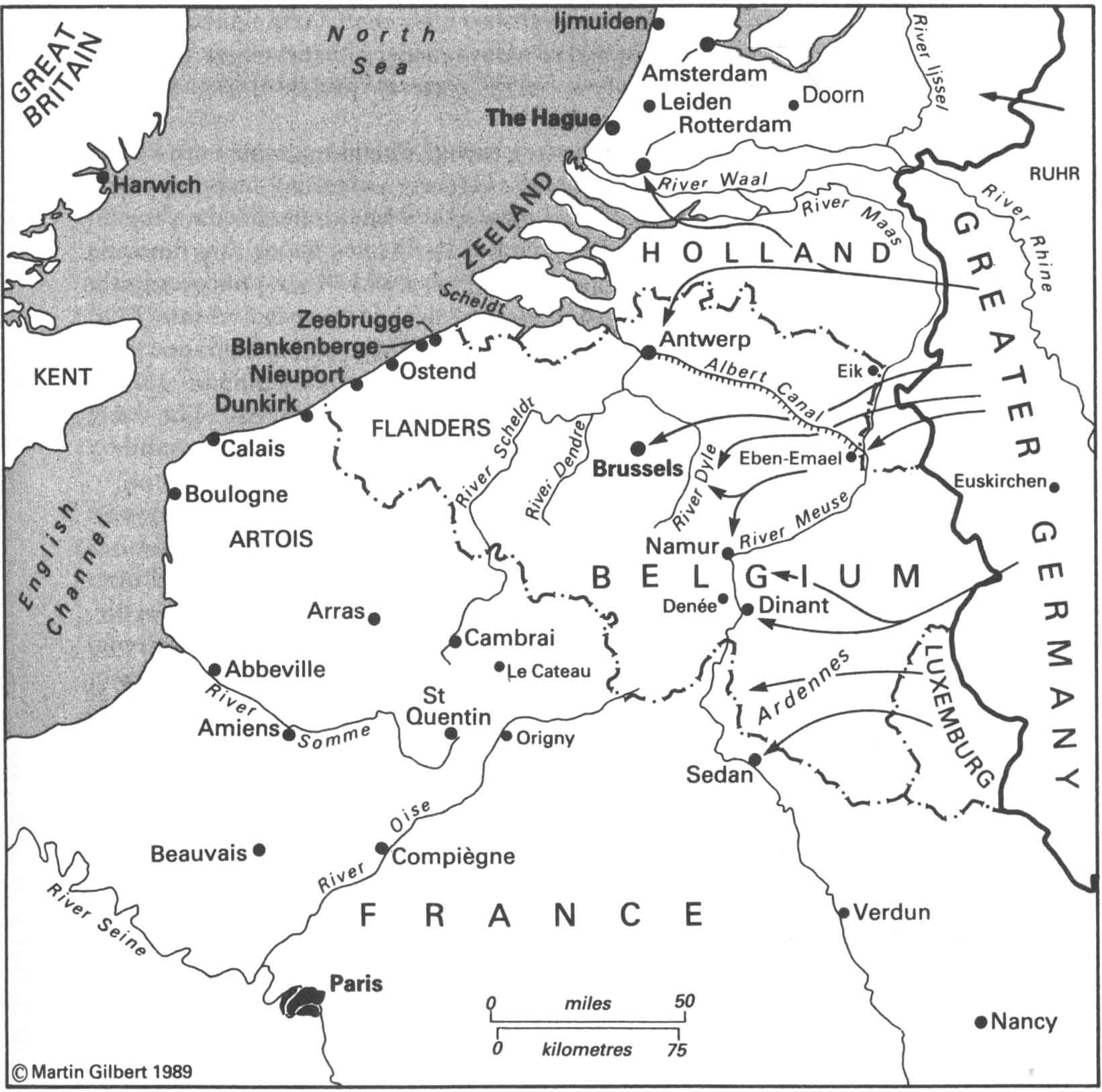

As dawn broke on the morning of 10 May 1940, the German forces advanced into Belgium and Holland; 136 German divisions, facing half that number of Allied troops. For the British and French, as a result of the earlier Belgian insistence on strict neutrality, the first Allied advance had to be across the French border and through Belgium to the line of the River Dyle. As the Allies moved forward, 2,500 German aircraft attacked the airfields of Belgium, Holland, France and Luxemburg, destroying many aircraft on the ground. Commanded by General Kurt Student, 16,000 German airborne troops, the spearhead of the German attack on Holland, parachuted into Rotterdam, Leiden and The Hague. A hundred German troops, landing silently in gliders as dawn broke, had seized the Belgian bridges across the Albert Canal.

Dominating the Albert Canal defences was the Belgian fortress of Eben-Emael. For six months an elite group of German parachutists had trained for its capture. Fifty-five of them landed at the fort at the very moment of the opening of the German offensive, but throughout May 10 the Belgian defenders, protected by massive gun emplacements, held out against considerable explosive charges and firepower.

In London, at seven o’clock that morning, an appeal for help was received from both the Dutch and Belgian governments. The British Government at once gave orders for mines to be dropped into the River Rhine, a decision made more than a month earlier, but, on account of the sudden Norwegian crisis, never implemented. An hour later it was learned in London that German aircraft had dropped mines into the Scheldt; German troops had crossed into Luxemburg; the French city of Nancy had been bombed, and sixteen civilians killed.

That morning, the British Government authorized Operation XD, to demolish the Dutch and Belgian port installations at the mouth of the Scheldt, in the event of a German thrust that far. Shortly after four o’clock that afternoon Hitler learned that the 4th German Panzer Division had crossed the River Meuse. Half an hour later, in London, Neville Chamberlain announced to his War Cabinet that, with the new emergency, a coalition government was essential, bringing the Labour and Liberal opposition parties into the war-making circle. But the Labour Party leaders had refused to serve under his leadership; for them, he was the man principally responsible for Britain’s lack of preparedness, even though they themselves had voted against conscription in April 1939.

With the Labour Party unwilling to serve under his leadership, Chamberlain had little option but to resign. He was succeeded as Prime Minister by Winston Churchill, the principal critic of his pre-war policies, and a man whom the Labour leaders believed would have the will and ability to direct the war with energy and zeal. A new government was formed, in which members of all the political parties had a place; Churchill becoming Minister of Defence as well as Prime Minister, with additional authority as the head of a special Defence Committee, consisting of himself and the Chiefs of Staff, the task of which was to make the day by day, and if necessary hour by hour, strategic decisions.

Ronald Cartland, one of several Conservative MPs then serving on the Western Front, was delighted by the news from London. ‘Winston—our hope—he may yet save civilisation,’ was his comment in a letter home. Cartland’s own unit had moved that day into Belgium. ‘Crowds of evacuees,’ he wrote. ‘I’m sorry for the Belgians, second time in twenty-five years, but they’re very brave and resolute.’

In spite of bravery, the superior German firepower was overwhelming; shortly before midday on May 11 the Belgian defenders of Fort Eben-Emael surrendered. Twenty-three of the seven hundred defenders had been killed. Of the fifty-five German attackers, six were dead. Hitler, who had literally hugged himself with joy on learning of the fort’s capture, personally decorated all the surviving attackers with the Iron Cross. The first Iron Cross of the campaign, however, was awarded to an SS officer, Captain Krass, of the Leibstandarte regiment, who, on the morning of May 11, crossed the Ijssel river in Holland with a small patrol, penetrated forty miles into Dutch territory, and brought back a hundred Dutch soldiers whom he and his little force had captured during their incursion.

At the Dutch town of Doorn, the former German Kaiser had lived in exile since 1919, when the Dutch Government had refused to extradite him to Britain to be tried as a war criminal. Now, as one of the first acts of the Churchill Government, the ex-Kaiser was asked if he would like to come to Britain, to escape the Nazis. He declined; and, a few hours later, Doorn was overrun.

For the Allies, the news of German successes came not only from Holland and Belgium; on the morning of May 11 it was learned in London that the Allied base at Harstad, north of Narvik, was being severely bombed by German aircraft, while at the same time German troops, taking advantage of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, were being moved by rail from Leningrad to Murmansk, as part of a possible pincer attack into northern Norway. Churchill’s instinct, on this, his first full day as Prime Minister, was to move the troops at Harstad southward to Mosjöen, where a small British garrison was still holding out; but the Chiefs of Staff argued that, in view of the ‘life and death struggle on the Western Front’, there were insufficient troops to hold either Mosjöen or Bodö—like Narvik, north of the Arctic Circle—which Churchill also hoped to reinforce. As was to happen throughout the war, when Churchill’s suggestions were strongly opposed by his Chiefs of Staff, those plans were abandoned. The British Prime Minister, unlike Hitler, had no power to overrule his principal strategical advisers. He was able, however, to support their recommendations with considerable vigour, and to insist upon their rapid implementation; on his first day as Prime Minister, British forces occupied the Danish dependency of Iceland, an important strategic base, and one which had to be denied to the Germans, now that they were rulers of Denmark. Now the need was to develop Iceland’s naval and air bases and facilities as quickly as possible.

The German invasion of Western Europe, May 1940

On the Western Front, the German commanders had vied with each other during May 11 on how far they could advance. ‘Everything wonderful so far,’ General Rommel, commanding the 7th Panzer Division, wrote to his wife that day, and he added: ‘Am way ahead of my neighbours’. On May 12, in Holland, after a march of a hundred miles, the German Eighteenth Army linked up with the paratroops who had been dropped two days earlier. That evening, the British War Cabinet were told that seventy-six British aircraft had been lost in the two days of fighting.

On May 13 Rommel’s troops, advancing through Belgium, crossed the Meuse at Dinant. That same day, further south, General Guderian’s troops pushed through the Forest of the Ardennes and crossed the Meuse near Sedan, the first substantial German crossing of the French border. At five o’clock that morning King George VI, asleep at Buckingham Palace, was woken by a police sergeant to be told that the Dutch Queen, Wilhelmina, wished to speak to him. ‘I did not believe him,’ the King wrote in his diary, ‘but went to the telephone and it was her. She begged me to send aircraft for the defence of Holland. I passed this message on to everyone concerned and went back to bed.’ The King commented: ‘It is not often that one is rung up at that hour, and especially by a Queen. But in these days anything may happen, and far worse things too.’

Queen Wilhelmina, warned that she might be kidnapped by the Germans and used as a hostage, left The Hague for Rotterdam, where she embarked on a British destroyer, the Hereward. Her aim was to join those of her armed forces still resisting in Zeeland. Heavy German bombardments made it impossible, however, for her to land; she therefore crossed the North Sea to Harwich, determined to make one further appeal for British air support. Once at Harwich, however, it was made clear to her that the situation in Holland was hopeless. That evening she was met by King George VI at Liverpool Street station in London. ‘I had not met her before,’ the King noted in his diary. ‘She told me that when she left The Hague she had no intention of leaving Holland, but force of circumstances had made her come here. She was naturally very upset.’

That afternoon, Churchill told the members of his new Government: ‘I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.’ He repeated those words a few hours later in the House of Commons, telling the Members of Parliament: ‘You ask, what is our policy? I will say. It is to wage war, by sea, land and air, with all our might and with all the strength that God can give us; to wage war against a monstrous tyranny, never surpassed in the dark, lamentable catalogue of human crime. That is our policy.’

As to what Britain’s aim might be, Churchill was equally emphatic. ‘It is victory, victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror, victory however long and hard the road may be; for without victory there is no survival.’

That evening, in the War Cabinet, Churchill learned that whereas the Air Staff estimated that sixty fighter squadrons were needed for the ‘adequate defence’ of Britain, only thirty-nine were available. The areas of Allied initiative were few and scattered. That night, several hundred aerial mines were dropped in the Rhine, disrupting German barge traffic near Karlsruhe and Mainz. For this enterprise, two Distinguished Service Crosses, and seventeen Distinguished Service Medals, were awarded. In Norway, even further from the decisive battle, French forces commanded by General Béthouart landed near the tiny fishing village of Bjerkvik, thirty miles from Narvik by road. ‘I hope you will get Narvik cleared up as soon as possible,’ Churchill telegraphed on May 14 to the British commander, Lord Cork, ‘and then work southwards with increasing force.’ It was a forlorn hope; yet after the French Foreign Legion, on May 15, had captured Bjerkvik, taking seventy prisoners, it was a hope that Churchill refused to abandon.

On the morning of May 14, confronted by a stronger Dutch defence than he had envisaged, Hitler included in a directive of that day an order to break Dutch resistance. ‘This resistance must be broken quickly,’ the order read. German aircraft were at once diverted from the Belgian frontier ‘to facilitate the rapid conquest of Fortress Holland’. Their target was the bridges over the River Maas at Rotterdam. Many bombs, missing their target, fell on the city centre; 814 Dutch civilians were killed. Rumour, and Allied propaganda, quickly multiplied the figure to 25,000, even 30,000. The reality was harsh enough. The rumour gave added terror to the lives of those in France and Belgium who were as yet unbombed.

At midday, grave news reached the Allied commanders. Near Sedan, the Germans had greatly enlarged the bridgehead established earlier by Guderian. It now became possible that, with substantial British and French forces pinned down in Belgium, the Germans would be able to use this bridgehead as a base for operations to sweep behind the Allied armies, pushing through the Ardennes in a broad semi-circle to the Channel ports. This was indeed Hitler’s plan. ‘The progress of the offensive to date’, he noted in his Directive No. 11, issued that day, ‘shows that the enemy has failed to appreciate in time the basic idea of our operations.’

Seriously alarmed, the French High Command asked the British for the maximum of air support in the Sedan sector. This was promptly given. In all, seventy-one British bombers were sent to the southern sector. Attacking the German pontoon bridges and troop columns in successive waves, they were savagely mauled both by the German fighters and by anti-aircraft defences on the ground. By nightfall, forty of the seventy-one British planes had been lost. One of those shot down, Flight Lieutenant Parkinson, managed to make his way to the French front line, but was shot at and severely wounded. Later, escaping from France, he served once more as a pilot; later, on an operation dropping supplies to the French Resistance, he was again shot down. This time, he was killed.

The failure of the British bomber offensive to halt the German advance through Sedan was matched by a failure of the French troops to hold the line. Hitler’s sweep behind the Allied lines had begun; within a month it was to have cut off the British Expeditionary Force from the main battle, and left Paris vulnerable to a swift advance. The British and French had still, on May 14, to extricate themselves from Norway. That day the British base at Harstad was attacked with incendiary bombs and two Allied ships destroyed. A third ship, the Polish liner Chrobry, was taking a battalion of the Irish Guards, four hundred troops in all, south to Bodö, when it was attacked; the twenty soldiers killed included the Commanding Officer, and every senior officer in the battalion.

There was a glimmer of good news for the Allies on May 14, when Arthur Purvis, head of the Anglo-French purchasing mission in Washington, reported that, of a hundred fighter planes then being built in the United States, Britain would be allowed to purchase eighty-one; of 524 further aircraft on order, 324 would be ready for delivery ‘within two or three months’.

The diversion of so many aircraft to Britain represented, Purvis explained, ‘real sacrifices by United States Services, as many squadrons on account of this will not be able to get their complement of modern planes’. This decision, vital for Britain at least in the long term, Purvis attributed to the ‘goodwill’ both of Roosevelt and of his Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, who had gone so far as to give an ‘emphatic assurance’ that the new orders being placed by the United States Army Air Force, as part of its own expansion programme, would not be allowed to interfere with Britain’s existing orders.

These benefits to come were not only long term, but secret. On May 14 the full focus of Allied fears was on Holland and the Ardennes. In Holland, the airborne forces of General Student had entered Rotterdam and were negotiating the city’s surrender. Student himself, before concluding the negotiations, watched while his men began disarming a large party of Dutch troops. SS troops, arriving at that moment and seeing so many armed Dutch soldiers, opened fire. Student himself was shot in the head. But for the skill of a Dutch surgeon who operated on him that night, he would almost certainly have died.

The French had by now begun to panic. Shortly after seven o’clock on the morning of May 15, Paul Reynaud telephoned Winston Churchill to say that a French counter-attack on the German forces which had broken through at Sedan had failed, that ‘the road to Paris was open’ and that ‘the battle was lost’. Reynaud went on to talk of ‘giving up the struggle’. Churchill did his best to calm the French Prime Minister. He must not be misled, he said, by ‘panic-stricken’ messages. But Churchill was under no illusions about the gravity of the situation. ‘The small countries’, he telegraphed to Roosevelt on May 15, ‘are simply smashed up, one by one, like matchwood.’ As for Britain, Churchill added, ‘We expect to be attacked here ourselves, both from the air and by parachute and air-borne troops in the near future, and are getting ready for them.’

Churchill’s confidence was also seen in the mood of the British troops in France. Ronald Cartland, writing to his mother on May 15, shortly before his unit withdrew from the line of the Scheldt, was in fighting, if sombre, mood: ‘We shall win in the end, but there’s horror and tribulation ahead of all of us. We can’t avoid it.’ To the south, where Rommel had crossed the Meuse, French tanks at the village of Denée engaged in a desperate attempt to halt the German thrust. As tank after tank was disabled, the Germans kept up a relentless barrage of fire. The commander of one company, Captain Gilbert, was killed by machine gun fire with most of his crew, when getting out of his blazing tank. By nightfall, sixty-five French tanks had been destroyed, and twenty-four Frenchmen killed. They had given their lives at a high price, destroying at least thirty of Rommel’s panzers. One of the French company commanders, Captain Jacques Lehoux, killed when his tank blew up, was posthumously made a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur. His principal adversary in the battle, Major Friedrich Filzinger, was awarded the Knight’s Cross; it was given to him by Hitler personally three weeks later.

On the evening of May 15, British troops were still landing at the Dutch port of Ijmuiden, in a last minute attempt to bolster Dutch resistance. As they landed, six buses reached the port from Amsterdam. On them were two hundred Jews, mostly children, being brought to the port by a Dutch woman, Geertruida Wijsmuller. Many of her charges were German—Jewish children who had managed to reach Holland before the war. Now they were on the move yet again. ‘At seven o’clock we sailed,’ one of the boys, Harry Jacobi, later recalled. ‘Far away from the shore we looked back and saw a huge column of black smoke from the oil storage tanks that had been set on fire to prevent the Germans having them. At 9 p.m. news came through, picked up by the ship’s radio. The Dutch had capitulated.’ The children found safety in Britain.

Hitler was now the ruler of yet another European State. In Holland, Harry Jacobi’s grandparents, for whom there had been no place on the crowded coaches, were to be among his tens of thousands of Dutch Jewish victims. That night, for the first time since the German Army had struck in the West five days earlier, British bombers attacked German industrial targets in the Ruhr. In all, seventy-eight bombers set off. All returned safely, although sixteen had failed to locate their targets. Twenty-four found oil targets, some of which were seen by the crews burning fiercely as they turned for home.

Unable to breach American neutrality by shipping aircraft to Britain uncrated and ready to fly, Roosevelt himself proposed, on the night of May 15, a way round a surviving provision in the Neutrality Act. This was to fly the aircraft to the American side of the Canadian border, ‘push’ them across the border, then fly them on to Newfoundland, where they could be put on board ship. ‘We already know’, Purvis reported to London, ‘this method is legal and feasible.’

Throughout May 16 the German advance continued, with Rommel penetrating fifty miles into French territory, towards Cambrai, and Guderian reaching a point sixty miles east of Sedan. That day General Gamelin ordered French forces to leave Belgium. Churchill, on his way to Paris, gave orders for Operation XD to be carried out at once. At Antwerp, as part of this demolition scheme, two British officers, Lieutenant Cadzow and Lieutenant Wells, drained off 150,000 tons of fuel into the Scheldt.

Reaching Paris that afternoon, Churchill urged an Allied military stand on the line Antwerp—Namur. ‘We have lost Namur’ was Reynaud’s comment. The French, led by Gamelin, then pressed for six extra British fighter squadrons to be sent to France, in addition to the four already there, and a further four to which the War Cabinet had agreed, that morning, in London. But Churchill pointed out that Britain’s own air defences were already in jeopardy; she had only thirty-nine squadrons for her own defence, four of which had now been allocated to work in France. But the urgency of the French request caused Churchill to put it, by telegram, to his War Cabinet. ‘It would not be good historically,’ Churchill warned, ‘if their requests were denied and their ruin resulted.’ In addition, one must not underrate ‘the increasing difficulties’ of the German advance ‘if strongly counter-attacked’.

That night, the War Cabinet agreed that three further British squadrons, based in Britain, would ‘work in France from dawn till noon’, after which a second three squadrons would replace them ‘for the afternoon’. This would at least save them from the danger of being attacked on the ground at French airfields.

In Paris, fears of an imminent German breakthrough led to panic. Bundles of official documents, thrown from the windows of the French Foreign Ministry, were set alight on the ministry lawn. But it was not towards Paris that Guderian’s panzers were advancing. Instead, they turned north-west, and by noon on May 17 had reached the River Oise, at Origny, less than ten miles east of St Quentin. Attacking them, but unable to halt them, were the tanks of the French 4th Armoured Division, commanded by one of the pioneers of armoured warfare, Colonel de Gaulle. In recognition of his bravery that day he was promoted to the rank of brigadier-general.

On every sector of the front the Germans were succeeding beyond their hopes. On May 17 troops of General von Reichenau’s Sixth Army entered Brussels, the fifth capital to be occupied by German troops in nine months. Falling back from Brussels towards the Channel coast, the British 3rd Division, commanded by General Bernard Montgomery, took up its position on the line of the River Dendre. Only at Hitler’s headquarters did there seem to be a moment of doubt. ‘A very disagreeable day!’ General Halder noted in his diary. ‘The Führer is excessively nervous. He mistrusts his own success; he’s afraid to take risks; he’d really like us to stop now.’

Hitler’s nervousness was misplaced. On May 18 his panzer commanders continued their advance at the same swift pace as before, Rommel reaching Cambrai and Guderian occupying St Quentin. One of France’s senior commanders, General Giraud, entering Le Cateau with the remnants of the French Ninth Army, was captured by the Germans—unknown to Giraud, German troops had reached the town a few hours earlier. During the day, Belgium’s principal port, Antwerp, fell to the Germans. ‘I do not need to tell you about the gravity of what has happened,’ Churchill telegraphed to Roosevelt. ‘We are determined to persevere to the very end, whatever the result of the great battle raging in France may be. We must expect in any case to be attacked here on the Dutch model before very long and we hope to give a good account of ourselves.’

The ‘Dutch model’ was the use of parachute troops to seize the vital points. It was to protect Britain against the ‘large number’ of German troops that might be landed from transport aircraft ‘preceded by parachutists’ that Churchill and the Chiefs of Staff considered the possibility, on May 18, of bringing British troops from as far away as Palestine, and even India, by the fastest possible naval convoy.

In Paris, fearful of subversion, the new Minister of the Interior, Georges Mandel, began on May 18 a massive round-up of suspicious persons. ‘Numerous arrests have been made in the street,’ a Canadian businessman recalled at the end of the month. ‘Traffic is strictly controlled. Policemen, bayonets fixed, stop passers-by and ask for identification.’

As the battle for France continued, British morale was boosted by the belief that the bombing raids over the Ruhr, begun on May 15, and continued for the next three nights, had been effective. But when the American journalist, William Shirer, drove on May 19 through the Ruhr he could see ‘very little damage’. As for the population, on whose morale the raids were said by the British Broadcasting Corporation to have had ‘a deadly effect’, Shirer found them, ‘especially the womenfolk, standing on the bridges over the main roads cheering the troops setting off for Belgium and France’. The only sign of the Royal Air Force’s presence which Shirer noted that day was near Hanover, where he saw a large British bomber ‘lying smashed in a field a hundred yards off the Autobahn’.

That day, in France, the SS Death’s Head Division saw action for the first time, when it was ordered to go to the assistance of Rommel’s 7th Panzer Division near Cambrai. Their adversaries were French Moroccan troops, whose defence of several small villages was tenacious. The SS troops fought with an equal fury, killing two hundred Moroccans for the loss of only sixteen SS men. That night Churchill broadcast to the British people, his first broadcast as Prime Minister. ‘This’, he said, ‘is one of the most awe-striking periods in the long history of France and Britain. It is also beyond doubt the most sublime.’ The British and French peoples, side by side, ‘have advanced to rescue not only Europe but mankind from the foulest and most soul destroying tyranny which has ever darkened and stained the pages of history’. Behind the armies and fleets of Britain and France there gathered ‘a group of shattered States and bludgeoned races: the Czechs, the Poles, the Norwegians, the Danes, the Dutch, the Belgians—upon all of whom the long night of barbarism will descend, unbroken even by a star of hope, unless we conquer, as conquer we must; as conquer we shall’.

How Britain and France could conquer was, at that moment, quite unclear. It was they, not Germany, that seemed about to succumb. That morning, as the German thrust threatened to drive a wedge between the British and French forces north and south of the River Somme, Churchill ordered the British Admiralty to assemble ‘a large number of vessels’ in readiness to cross over ‘to ports and inlets on the French coast’. It was now clear, he told the Admiralty, that plans must be made at once, in case it became necessary ‘to withdraw the British Expeditionary Force from France’. Plans were also made, that day, for ‘mobile columns’ to reinforce airport guards in case of German parachute landings in Britain. Even London was now felt to be a possible target of such landings; on May 20 Churchill approved a scheme of Bren gun posts and barbed wire road blocks to protect the Government offices in Whitehall, and 10 Downing Street itself, from a German attempt to seize the centre of the capital.

That night, German armoured columns, reaching Amiens, pushed on towards Abbeville, cutting off the British Expeditionary Force from the main French Army, and from its own bases and supplies in Western France. Hundreds of thousands of British, French and Belgian soldiers were now trapped, with their backs to the sea. Hitler was elated. General Jodl, who was present, noted that Hitler ‘Talks in words of appreciation of the German Army and its leadership. Busies himself with the peace treaty which shall express the theme, return of territory robbed over the last four hundred years from the German people….’ Hitler would ‘repay’ the French for the peace terms imposed upon Germany in 1918 by conducting his own peace negotiations at the same spot in the forest of Compiègne. As for the British, ‘The British can have their peace as soon as they return our colonies to us.’

Hitler, in his elation, was already musing about peace terms. But west of Compiègne, the bloody business of war went on; that evening, near Beauvais, two German airmen were shot down in an area over which German planes had been machine-gunning French and Belgian refugees as they sought to flee southwards. Both airmen were unarmed. As they stood by the roadside, surrounded by a crowd of civilians, a French soldier went up to them, drew his pistol and shot one of the Germans in the head, killing him instantly. The dead airman was the twenty-three year old Sergeant Wilhelm Ross; he was buried by the roadside, one of 1,597 Germans ‘killed in action’ that week in western France. Another German soldier who died on May 20, as a result of injuries sustained in battle, was Prince Wilhelm of Hohenzollern, the grandson of the ex-Kaiser, and heir to the German Imperial throne. The ex-Kaiser himself, in exile in Holland since 1918, having refused an offer from Churchill to come to Britain on 10 May, remained in Holland, his place of exile at Doorn being first overrun and then guarded by the successors to those very armies which he had launched against France and Belgium in 1914.

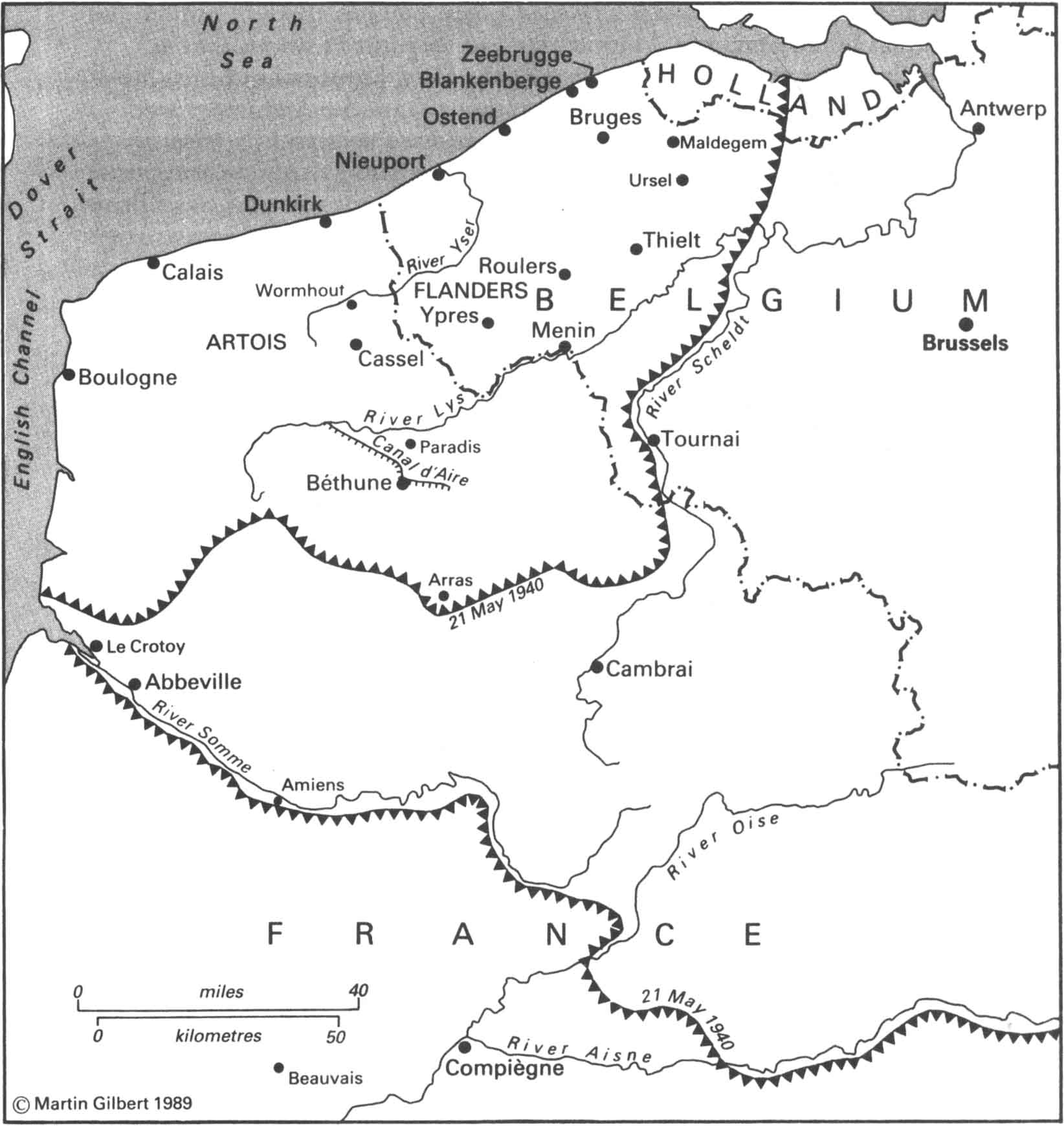

On May 21, German troops reached Le Crotoy, a small seaside resort on the Channel coast, at the mouth of the River Somme. With their arrival at Le Crotoy, the Allied armies in France were cut in half. The way was now open for Hitler’s forces to drive the British back to the North Sea coast, and to destroy them. This very danger led, that day, to a British counter-attack at Arras by fifty-eight tanks under General Martel which caused near panic to Rommel’s 7th Panzer Division. Eighty-nine of Rommel’s men were killed, four times the losses he had suffered during the breakthrough into France. The SS Death’s Head Division, sent once more to Rommel’s support, knocked out twenty-two tanks, but lost thirty-nine men. Only the arrival of German dive bombers averted further losses.

For the first time in eleven days of battle, German troops had been forced back; nor was it troops alone, but the prized panzers, on whom so much depended. Hitler, concerned lest the panzers should be mauled still further, and fearing that the British would fight in France to the last man, ordered a halt to the advance against the Channel ports.

In the East, the war against the mentally ill took a new turn on May 21, when a so-called ‘Special Unit’ was sent to Soldau, in East Prussia, to kill more than 1,500 mental patients who had been transferred there from hospitals throughout East Prussia. The killings were completed in eighteen days; when they were over, the Special Unit reported back to Berlin that the mental patients had been ‘successfully evacuated’.

On the Western Front, the British and French now planned a counter attack, to link up their forces across the German spearhead, with General Weygand, whose plan it was, promising to attack the Germans from the south. That night, in Britain, the head of the British Union of Fascists, Sir Oswald Mosley, and thirty-five other leading members, were arrested, to be joined in prison within a week by 346 of their followers.

Dunkirk, May 1940

May 22 marked an important, and indeed dramatic stage in Britain’s ability to read some of the most secret German wireless communications, for on that day the decrypters at Bletchley Park broke the German Enigma key most frequently used by the German Air Force. Henceforth British Intelligence was able to read, each day, every German Air Force message sent from headquarters to the field, and from the field to headquarters. Among the most important of these were messages sent by the German Air Force liaison officers with the German Army; these messages provided many pointers to the position and intentions of the German field formations, as they turned towards the sea.

The ‘flood of operational intelligence’, the official historians of British Intelligence have written, was ‘decrypted, translated, amended and interpreted’ at the rate of a thousand messages a day. These were then sent by teleprinter or courier to Whitehall. At the same time, beginning on May 24, the most important items were passed direct from Bletchley to the headquarters of the British Expeditionary Force, and to Air headquarters. To ensure that the Germans never learned that their most secret method of communication had been breached, a special cypher was used, sent by a special signals link, through a Secret Intelligence Service mobile unit which assisted the commanders-in-chief in the interpretation of the material, and advised on how it could be exploited.

The breaking of the Enigma provided the British commanders, then at their most stretched, with a valuable window on to German Air Force activities and intentions, and on many of the activities and intentions of the German Army. It took some time, however, for those at Bletchley to master the many problems. ‘Apart from their sheer bulk,’ the historians of Enigma tell us, ‘the texts teemed with obscurities—abbreviations from units and equipment, map and grid references, geographical and personal code names, pro-formas, Service jargon and other arcane references,’ not to speak of the difficulties sometimes created by poor interception or by textual corruption as a result of the messages having been sent in the heat of battle. A particular difficulty during the early days of decryption that May was that the German Air Force headquarters, in its instructions, and the German commanders in the field, in their replies, made frequent reference to points on a British General Staff map series, scale 1:50,000, which had long ago been withdrawn from use in the British Army. Unable to obtain a set of these maps, the cryptographers at Bletchley were forced to reconstruct them from the German references to them, a laborious process. Despite these difficulties, information was yielded which could have been invaluable had the British Army not been in headlong retreat.

The British forces falling back to the sea were spared an immediate German onslaught, not as a result of any Intelligence coup, but because the Germans, having split the Allied armies, treated the troops in Flanders as a secondary target compared with the French troops falling back towards Paris. Nor were the Germans aware of just how many men were trapped towards the coast; German estimates on May 23 were of only 100,000, a quarter of the real figure. In addition, the General upon whom the main responsibility for the attack would lie, Ewald von Kleist, had seen almost fifteen per cent of his transport put out of action in the previous two weeks of fighting; he therefore welcomed the pause which Hitler had ordered. Nor did it seem possible that the British forces would be able to be evacuated by sea. Goering had assured Hitler that the German Air Force could prevent that. There was therefore no urgency in attacking in force the men who, on May 21, had shown themselves capable of so spirited and costly a counter-attack. On May 23, therefore, at six in the evening, General von Rundstedt, on his own initiative, issued orders to the German Fourth Army to ‘halt tomorrow’.

Knowing nothing of Rundstedt’s order, the British Army still waited for the planned French counter-attack from the south. At ten o’clock that night Churchill went to see the King at Buckingham Palace. ‘He told me’, the King wrote in his diary, ‘that if the French plan made out by Weygand did not come off, he would have to order the BEF back to England. This operation would mean the loss of all guns, tanks, ammunition and all stores in France’. ‘After ten days,’ Ronald Cartland wrote to his mother from the British Expeditionary Force on May 23, ‘we’re back now in the same place from where we started. It’s a rum war!’

‘On the go all day of course,’ General Rommel wrote to his wife on May 24. ‘But by my estimate the war will be won in a fortnight.’ Hitler, visiting von Rundstedt’s headquarters that day, predicted that the war would be over in six weeks. Then the way would be free for an agreement with Britain. Hitler and Rundstedt then discussed the fate of the British troops trapped on the Channel coast. The two men were agreed that air attack could be used against the besieged perimeter. But Rundstedt went on to propose that his tanks should halt once they reached the canal below Dunkirk, so that his armoured forces could be saved for operations against the French. Hitler agreed. Shortly after midday, a second ‘halt’ order was issued to the Fourth Army in Hitler’s name. For the time being, all attacks in the Dunkirk perimeter were to be ‘discontinued’.

One effect of the second ‘halt’ order was that the SS Death’s Head Division, in order to strengthen the line near Béthune, had to make a small withdrawal across the Canal d’Aire. The British, noting the German move, began an intense artillery barrage, during which forty-two SS men were killed.

When, late that evening, General Halder sent Rundstedt permission to attack Dunkirk, Rundstedt refused, telling Halder: ‘the mechanized groups must first be allowed to pull themselves together’. ‘Contrary to expectations,’ Hitler’s Army adjutant noted a few days later, ‘the Führer left the decision largely to Rundstedt.’ But it was only a decision to halt for a short while, to regather strength and to await reinforcements. The German aim was still a military victory. ‘The next object of our operations’, Hitler stated in his Directive No. 13 on May 24, ‘is to annihilate the French, English and Belgian forces which are surrounded in Artois and Flanders, by a concentric attack by our northern flank and by the swift seizure of the Channel coast in this area.’

While the German Army paused, the British evacuation began. On May 24 a thousand men were embarked from Boulogne. Two hundred more, however, could not be got away before German troops entered the port on the following morning. Above the sea, off Dunkirk, the air attack which Hitler had authorized began at once; on May 24 a French ship, the Chacal, was sunk. Off Calais, where the British garrison was cut off even from the Dunkirk perimeter, the destroyer Wessex was likewise sunk, and the Polish destroyer Bzura badly damaged, while bombarding German positions on the coast.

The British Government now began plans to evacuate the British troops from Dunkirk. To the east of the Dunkirk peninsula, however, the Germans had managed to drive a wedge between the British and Belgian forces holding the line between Menin and Ypres. ‘Soldiers!’, King Leopold of the Belgians exhorted his troops on May 25, ‘The great battle which we expected has begun. It will be hard. We will wage it with all our power and supreme energy.’ The battle was taking place, the King added, ‘on the same ground upon which we victoriously faced the invader in 1914’.

The Belgian soldiers, responding to the King’s appeal, continued to resist, but their counter-attacks, aimed at closing the gap, though mounted with considerable vigour, were repelled. Fortunately for the British, a German staff car, captured on May 25, contained a document giving precise details of the German plans to exploit the gap. As a result of this timely Intelligence, the British Commander-in-Chief, Lord Gort, was able to order into the gap two divisions which were preparing to attack elsewhere. These were, in fact, the very divisions which were to have pushed southward, out of the German trap, as the British part of the Weygand plan. Only by abandoning the possibly false hope of a breakthrough to the south could the perimeter be held whereby a sea evacuation was possible. That day, in pursuance of Hitler’s discussion with General von Rundstedt, the German Air Force threw all its available aircraft into an attack on the port installations of Zeebrugge, Blankenberge, Ostend, Nieuport and Dunkirk. Not realizing that Dunkirk was to be the main embarkation port, Goering directed the heaviest bombing against Ostend.

Despite Hitler’s ‘halt’ order, on May 25 a small combat unit of the SS Death’s Head Division, led by Captain Harrer, crossed the Canal d’Aire near Béthune, over which they had withdrawn on the previous day. Spotting a British motorcyclist speeding in their direction, one of the SS men opened fire, knocking the soldier off his machine. The SS men then approached him; he was lying in a ditch, wounded in the shoulder. Pulling him to his feet, the SS men tried, unsuccessfully, to converse with him. Captain Harrer then asked him, in halting English, if he spoke French. When the British soldier did not reply, Harrer drew his pistol and shot him through the head at point-blank range.